Abstract

Growth plate chondrocytes go through multiple differentiation steps and eventually become hypertrophic chondrocytes. The parathyroid hormone (PTH)-related peptide (PTHrP) signaling pathway plays a central role in regulation of hypertrophic differentiation, at least in part, through enhancing activity of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4), a negative regulator of MEF2 transcription factors that drive hypertrophy. We have previously shown that loss of the chondrocyte-specific microRNA (miRNA), miR-140, alters chondrocyte differentiation including mild acceleration of hypertrophic differentiation. Here, we provide evidence that miR-140 interacts with the PTHrP-HDAC4 pathway to control chondrocyte differentiation. Heterozygosity of PTHrP or HDAC4 substantially impaired animal growth in miR-140 deficiency, whereas these mutations had no effect in the presence of miR-140. miR-140–deficient chondrocytes showed increased MEF2C expression with normal levels of total and phosphorylated HDAC4, indicating that the miR-140 pathway merges with the PTHrP-HDAC4 pathway at the level of MEF2C. miR-140 negatively regulated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, and inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling reduced MEF2C expression. These results demonstrate that miR-140 ensures the robustness of the PTHrP/HDAC4 regulatory system by suppressing MEF2C-inducing stimuli.

Keywords: GROWTH PLATE, GENETIC ANIMAL MODELS, PTHRP, CELL/TISSUE SIGNALING, PARACRINE PATHWAYS, MOLECULAR PATHWAYS, DEVELOPMENT, BONE MODELING AND REMODELING, EPIGENETICS

Introduction

The growth plate is the primary driver of longitudinal bone growth. In order to achieve normal bone growth, differentiation and proliferation of chondrocytes, cellular components of the growth plate, need to be tightly regulated.(1) Growth plate chondrocytes go through multiple steps of differentiation. Resting chondrocytes (also called periarticular chondrocytes in embryonic stages), located at the most epiphyseal end, differentiate into vigorously proliferating columnar chondrocytes, and further differentiate into postmitotic hypertrophic chondrocytes. These processes are achieved by precisely controlled expression of genes that regulate chondrocyte differentiation.

Small regulatory microRNAs (miRNAs) modulate gene expression mainly at the posttranscriptional level. miRNAs are generally thought to serve as “genetic buffers” by suppressing expression of undesired genes to ensure the gene expression pattern unique to specific cell types.(2) Observations that manipulation of a single miRNA generally has a relatively modest effect support the idea of miRNAs as a secondary, “safeguard” regulatory system of gene expression.(3,4) This notion also implies that a miRNA may play critical roles when the primary regulatory system is impaired.

miRNA-140 (miR-140), generated from the Mir140 gene, is abundantly and relatively specifically expressed in chondrocytes. We and others have shown that loss of the Mir140 gene causes a mild skeletal growth defect in mice.(5,6) miR-140 deficiency alters chondrocyte differentiation at multiple steps; differentiation of resting zone chondrocytes into columnar chondrocytes is inhibited, whereas differentiation of proliferating chondrocytes into hypertrophic chondrocytes is accelerated. Because of the accelerated hypertrophic differentiation, miR-140–null bones show advanced mineralization; nevertheless, the effect of miR-140 loss in chondrocyte differentiation is relatively mild.

The signaling molecules, Indian hedgehog (Ihh) and parathyroid hormone (PTH)-related peptide (PTHrP) (Pthlh, Mouse Genome Informatics; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA; http://www.informatics.jax.org), play a central role in regulation of chondrocyte differentiation. Ihh regulates chondrocyte differentiation and proliferation as well as expression of PTHrP in resting/periarticular chondrocytes. PTHrP negatively regulates differentiation of Ihh-expressing hypertrophic chondrocytes through the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Thus, Ihh and PTHrP form an autoregulatory system that controls chondrocyte differentiation.(1)

MEF2 transcription factors, particularly MEF2C and MEF2D, play a critical role in regulation of hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation.(7) MEF2 activity directly controls hypertrophic differentiation; a reduction in MEF2 function through genetic ablation or overexpression of a repressive mutant MEF2 protein inhibits hypertrophic differentiation, whereas it is stimulated by MEF2 overactivity. Thus, signals that control hypertrophic differentiation appear to ultimately converge on regulation of MEF2 transcription factors. MEF2 activity is modulated by physiological regulators; class IIa histone deacetylases (HDACs) are some of the critical regulators of MEF2 transcription factors. Class IIa HDACs directly bind to MEF2 transcription factors to inhibit their function.(8,9) In chondrocytes, HDAC4 plays a particularly important role; Hdac4-null mice show acceleration of hypertrophic differentiation, a phenotype similar to that of PTHrP-null mice(10); this phenotype is rescued by heterozygous loss of Mef2c.(7)

Nuclear translocation primarily determines HDAC4’s activity. HDAC4 nuclear translocation is negatively regulated by direct binding of the chaperon protein, 14–3-3.(11) Dephosphorylation of the 14–3-3 binding site of HDAC4 dissociates HDAC4 from 14–3-3 and facilitates its nuclear translocation. The phosphorylation status of HDAC4 is determined by the balance between kinase and phosphatase activities. Salt-inducible kinases (SIKs) phosphorylate the 14–3-3 binding site of class II HDACs to suppress their nuclear localization. In chondrocytes, SIK3-deficiency increases nuclear HDAC4 and delays hypertrophic differentiation.(12) In contrast, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) dephosphorylates HDAC4 and facilitates its nuclear translocalization.(13,14)

Based upon the finding that PTHrP activates PP2A to dephosphorylate HDAC4 and increases its nuclear localization, it was proposed that PTHrP suppresses the function of MEF2 transcription factors by enhancing HDAC4’s inhibitory action on MEF2 transcription factors.(13)

Because Mir140-null mice show mild acceleration of hypertrophy, we hypothesized that the miR-140 pathway might interact with the PTHrP/HDAC4 pathway to reinforce the regulatory system controlling hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation. In this article, we present evidence that miR-140 modulates the PTHrP/HDAC4 pathway by suppressing MEF2C expression.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mir140,(6) Hdac4,(10) PTHrP,(15) and Ihh(16) knockout mice, Col2-PTHrP,(17) and Col2-caPPR(18) transgenic mice have been described. Mice were of a mixed genetic background. Comparisons were made between littermates. The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed in accordance with the regulations and guidelines.

Skeletal preparation and histology

Alizarin red and Alcian blue staining was performed using a modified McLeod’s method.(19) For histological analysis, mice were dissected, fixed in 10% formalin, decalcified in 10% EDTA, paraffin-processed, cut, and subjected to hematoxylin-eosin staining.

Primary chondrocyte isolation and culture

Isolation and culture of primary rib chondrocytes were performed as described.(6) After overnight culture, cells were trypsinized and replated at the concentration of 5 × 105/mL in DMEM containing 10% FCS. For assessment of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, upon reaching confluence, primary chondrocytes were serum-starved for 3 hours before stimulating with 10% FCS. Cells were lysed at indicated time points and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Retrovirus production and infection

The RalA overexpression (pBabe-Puro-hRalA-wt) virus has been described.(20) The virus expressing an active from of Rac1 (caRac1)(21) was constructed by cloning the coding sequence into the pMSCV-neo vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The retrovirus for GFP has been described.(22) The Dnpep-expressing virus was constructed by cloning a PCR-amplified mouse Dnpep cDNA using primers, Dnpep5, 5′-CAGAATTCGCCAGTGAAGTCCTCGGAAGC-3′ and Dnpep3, 5′-CTCTCGAGTGAAAATCTACTT TAATAACCAACA-3′ into the pMSCV-neo vector at the EcoR I and Xho I site (underlines are EcoR I and Xho I recognition sequences). The Creb3l1-expressing virus was constructed by cloning a PCR-amplified mouse Creb3l1 cDNA using primers, Creb3l1 × 5, 5′-TTCTCGAGTGGAACCCGGCGCGATGGA-3′ and Creb3l1R3, 5′-TTGAATTCCTGGGTCTTGGAGTGGCCTA-3′ into the modified pMSCV vector(22) at the and Xho I and EcoR I site (underlines are Xho I and EcoR I recognition sequences). To generate the miR-140 expression construct, first a fragment of Mir140 genomic sequence was PCR-amplified using primers, Pre-mir140–5 5′-CAAGGTTCCTGCCAGTGGTTTTACCCTATG-3′ and Pre-mir140–3, 5′-CAAGGTTCCTGTCCGTGGTTCTACCCTGTG-3′ and subcloned into the pTarget vector (Promega Madison, WI, USA). The Sal I/EcoR I fragment including the Mir140 sequence was further cloned into the Xho I/EcoR I site of the modified pMSCV vector, pMSCV-GFP.(22) These Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV)-based viruses were packaged using the EcoPack packaging plasmid (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Transfection and luciferase assay

DNA containing 0.18 μg of a Mef2 luciferase reporter vector(23) and 0.02 μg of a Renilla luciferase control vector was transfected into primary rib chondrocytes using the Attractene transfection reagent (Qiagen Valencia, CA, USA). Luciferase and Renilla activities were measured 24 hours after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Quantitative RT-PCR

cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamers using the DyNAmo cDNA Synthesis Kit (Finnzymes, Waltham, MA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems,Grand Island, NY, USA) and the Eva Green qRT-PCR mix(Solis Bio Dyne,Tartu, Estonia). Primer sequences were as follows : Actb-L, 5′-GCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGG-3′ and Actb-R, 5′-GTTCCGATGCCCTGAGGCTCTT-3′; GAPDH-L, 5′-CACAATTTCCATCCCAGACC-3′ and GAPDH-R, 5′-GTGGGTGCAGCGAACTTTAT-3′; Mef2c-L, 5′-CCCTTCGAGATACCCACAAC-3′ and Mef2c-R, 5′-ATGCGCTTGACTGAAGGACT-3′; Sox9-L, 5′-AGGAAGCTGGCAGACCAGTA-3′ and Sox9-R, 5′-CGTTCTTCACCGACTTCCTC-3′; RalA-L, 5′-GATGGAGTCCTTCGCAGCTA-3′ and RalA-R, 5′-ACGTTCCACTGGTCAGCTCT-3′; hRala-L, 5′-AAGTCATCATGGTGGGCAGT-3′ and hRala-R, 5′-AGCTGTCTGCTTTGGTAGGC-3′; Ihh-L, 5′-GAGCTCACCCCCAACTACAA-3′ and Ihh-R, 5′-TGACAGAGATGGCCAGTGAG-3′; Pthr1-L, 5′-CGCAGACGATGTCTTTACCA-3′ and Pthr1-R, 5′-TCCACCCTTTGTCTGACTCC-3′; Creb3l1-L, 5′-TCTTTGATGACCCTGTGCTG-3′and Creb3l1-R, 5′-TGGTGTCCTCCATCTTGACA-3′;hRalA-L,5′-AAGTCATCATGGTGGGCAGT-3′ and hRalA-R, 5′-AGCTGTCTGCTTTGGTAGGC-3′; and Rac1-L, 5′-TATGGGACACAGCTGGACAA-3′ and Rac1-R, 5′-ACAGTGGTGTCGCACTTCAG-3′.

Expression of miR-140 was determined using the mirVana qRT-PCR miRNA Detection Kit (Ambion, Waltham, MA, USA).

Western blot analysis

Anti-MEF2C (#5030), anti-HDAC5 (#2082), anti-Histone 2A (#2578), and anti-Phospho-HDAC4 (Ser246)/HDAC5 (Ser259)/ HDAC7 (Ser155)(#3443) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Denvers, MA, USA. Anti-MEF2D (BDB610774) was from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA, Anti-HDAC4 antibody (ab12172) was purchased from Abcam. AntiRalA antibody was from GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA. Anti-Sox9 antibody (bs-4177R) was from Bioss, Woburn, MA, USA. Anti-Actin antibody (I–19) was purchased from Santa Cruz, Dallas, Texas, USA Biotechnology. Anti-GAPDH antibody (10R-2932) was purchased from Fitzgerald Industries International, Acton, MA, USA. Western blot analysis was performed according to the standard procedure.

Results

Skeletal phenotypes of Mir140-null mice can be partially rescued by overactivation of PTHrP signaling

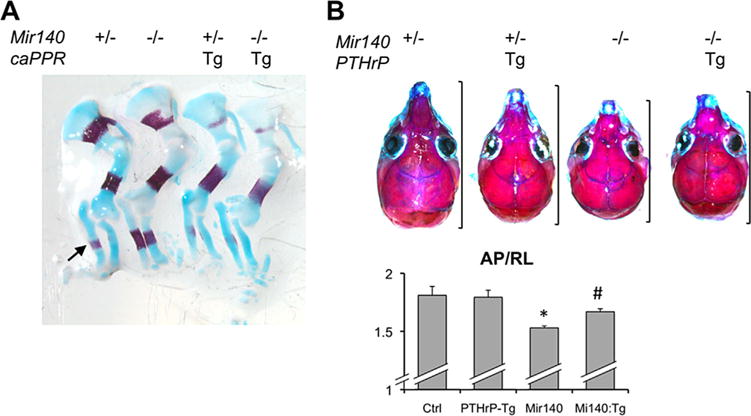

Loss of Mir140 causes a mild growth impairment and shortening of the longitudinal dimension of the skull.(6) Lengths of endochondral bones, including those in the basal skull, are reduced due to the decrease in number of columnar proliferating chondrocytes of the growth plate. The reduction in number of columnar chondrocytes is caused by an inhibition of differentiation of resting zone chondrocytes into columnar chondrocytes and an acceleration of hypertrophic differentiation of the columnar chondrocytes. Because hypertrophic differentiation is negatively regulated by PTHrP signaling, we hypothesized that Mir140 loss might compromise PTHrP signaling. In order to test this hypothesis, we first attempted to rescue the skeletal phenotype of Mir140-null mice by overactivating PTHrP signaling. In order to overactivate PTHrP signaling, we crossed Mir140-null mice with transgenic mice overexpressing a constitutively active PTH/ PTHrP receptor (PPR; Pthr1; Mouse Genome Informatics) in chondrocytes (Col2-caPPR) or transgenic mice expressing PTHrP (Pthlh) in chondrocytes (Col2-PTHrP). We used Col2-caPPR mice for long bone analysis because Col2-caPPR mice show relatively normal long bones except for a delay in the initial hypertrophic differentiation during embryonic stages, whereas Col2-PTHrP mice show severe deformities in long bones. In E14.5 embryos, Mir140 loss increased the size of the mineralized domain of the ulna and radius due to acceleration of chondrocyte hypertrophy,(6) whereas caPPR overexpression delayed mineralization (Fig. 1A). When caPPR was overex-pressed in Mir140-null (Mir140−/−) mice, the compound mutant (Mir140−/− Col2-caPPR) mice showed delayed mineralization, a phenotype similar to that of Col2-caPPR mice (Fig. 1A). Another prominent skeletal defect of Mir140-null mice was a longitudinal growth defect of the skull due to growth plate abnormalities of the basal skull.(6) This phenotype was partially corrected by simultaneous overexpression of PTHrP in chondrocytes (Col2-PTHrP), whereas PTHrP overexpression alone caused a mild global growth impairment but showed little effect on the skull shape, again demonstrating that overactivation of PTHrP signaling partially rescued skeletal defects of Mir140-null mice (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

PTHrP overactivity rescues skeletal phenotypes of Mir140-null mice. (A) Alcian blue/Alizarin red-stained forelimbs of E14.5 embryos of indicated genotypes. Mir140-null mice show advanced bone mineralization in the radius and ulna compared with control Mir140 heterozygotes (arrow), whereas transgenic expression of a constitutively active PTH/PTHrP receptor (caPPR) delays bone mineralization. Compound mutant mice, Mir140−/− caPPR show delayed mineralization similar to that of caPPR transgenic mice. This result was confirmed in 3 compound mutant mice. (B) Transgenic overexpression of PTHrP in chondrocytes ameliorates the shortening of the Mr140-deficient skull. Alizarin-red stained skulls of 3-week-old littermates of indicated genotypes. Brackets indicate the naso-occipital (anteroposterior, AP) length. The AP length relative to the skull width (RL) was calculated and compared among Mir140−/− (Ctrl), Mir140−/−:PTHrP-Tg (PTHrP-Tg), Mir140−/− (Mir140), and Mir140−/−:PTHrP-Tg (Mir140:Tg). *p < 0.01 versus Ctrl or PTHrP-Tg; #p < 0.05 versus Mir140; n ≥ 3.

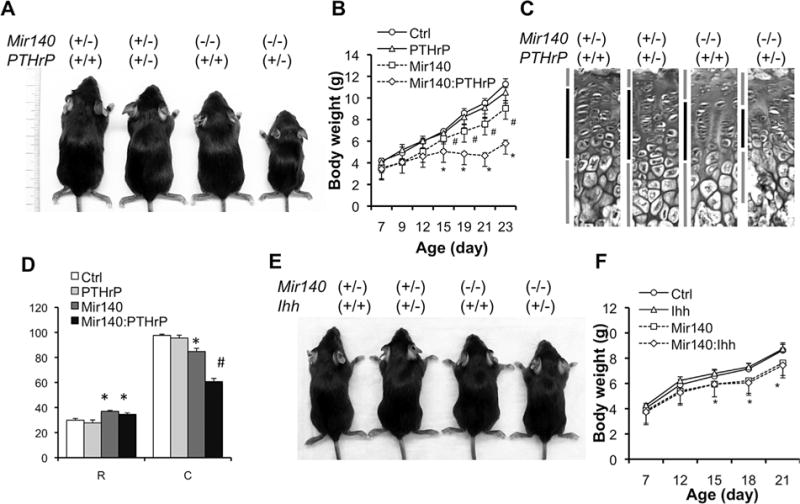

Mir140 deficiency and PTHrP heterozygosity synergistically impair skeletal growth

In order to test whether miR-140 interacts with the PTHrP signaling pathway, we crossed Mir140-null mice to PTHrP (Pthlh) heterozygous null (PTHrP+/−) mice. Whereas PTHrP+/− mice showed normal growth, and Mir140-null mice showed only a mild growth impairment, compound mutant mice (Mir140−/− PTHrP+/−) showed a significant growth defect compared with control or Mir140-null mice (Fig. 2A, B). Although the expansion of the resting zone was similarly present in the compound mutant mice, the columnar region of the growth plate was significantly shortened, suggesting premature hypertrophic differentiation (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

PTHrP heterozygosity exacerbates the growth defect of Mir140-null mice. (A) Pictures of 3-week-old littermates with indicated genotypes. (B) Growth curve of mice with indicated genotypes. Ctrl, Mir140+/− PTHrP+/+ (n = 6); PTHrP, Mir140+/− PTHrP+/− (n = 4); Mir140, Mir140−/− PTHrP+/+ (n = 5); Mir140:PTHrP, Mir140−/− PTHrP+/− (n = 7). #p < 0.05 versus Ctrl or PTHrP. *p < 0.05 versus Ctrl, PTHrP, or Mir140. (C) H&E-stained section of growth plates of the proximal tibia. Bars indicate the resting, columnar and hypertrophic regions. Doubly mutant mice show a significantly shorter columnar region than that of single mutants. (D) Quantification of growth plates of mice with indicated genotypes. Mice were euthanized at P23. The length of the resting zone (R) and the columnar proliferating zone (C) was measured. *p < 0.05 versus Ctrl or PTHrP; #p < 0.05 versus Ctrl, PTHrP, or Mir140; n ≥ 3. (E) Pictures of 3-week-old littermates with indicated genotypes. (F) Ihh heterozygosity has no effect on growth of Mir140-null mice. Ctrl, Mir140+/− Ihh+/+ (n = 7); Ihh, Mir140+/− Ihh+/− (n = 7); Mir140, Mir140−/− Ihh+/+ (n = 6); Mir140:Ihh, Mir140−/− Ihh+/− (n = 5). *p < 0.05 Ctrl or Ihh versus Mir140 or Mir140:Ihh.

Because Ihh is a critical upstream regulator of PTHrP, we also bred Mir140-null mice with Ihh heterozygotes (Ihh+/−). Ihh heterozygosity did not cause detectable skeletal growth defects, and Mir140−/− Ihh+/− compound mutant mice also showed growth identical to that of Mir140−/− mice (Fig. 2E, F). This result may suggest that miR-140 functions at a level downstream of the PTHrP and PTHrP receptor in the Ihh-PTHrP system. Alternatively, the possible reduction of Ihh signaling in Ihh heterozygous knockout mice may not be sufficient enough to bring out the effect of miR-140-deficiency.

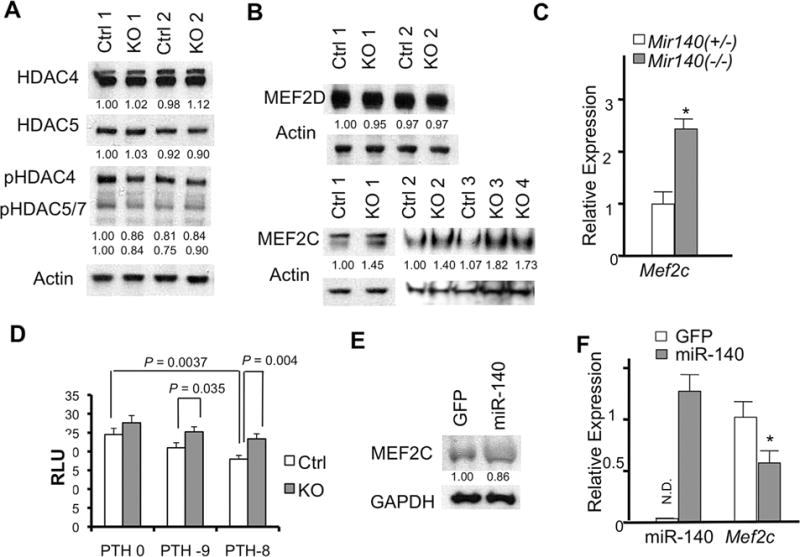

The miR-140 pathway and PTHrP pathway converges on MEF2 regulation

Using primary rib chondrocytes, we investigated the effect of miR-140 deficiency on components of the PTHrP/HDAC4 pathway. There were no overt changes in the protein level or phosphorylation status of HDAC4 or HDAC5 in Mir140-null chondrocytes (Fig. 3A). We also found that intracellular localization of HDAC4 was not altered (Supporting Fig. 1). However, we found that the level of MEF2C, but not MEF2D, was upregulated in Mir140-null mice (Fig. 3B). MEF2C upregulation was likely due to the increased Mef2c transcript abundance (Fig. 3C). We also found that the MEF2 transcriptional activity, assessed by a luciferase reporter assay, was mildly, but significantly, increased in PTH-treated Mir140-null chondrocytes (Fig. 3D). Conversely, overexpression of miR-140 in primary rib chondrocytes missing Mir140 via retrovirus-mediated transduction decreased MEF2C expression level both at the protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 3E, F).

Fig. 3.

Mir140 loss upregulates MEF2C expression and function. (A) Expression or phosphorylation of class II HDACs in primary rib chondrocytes is not affected in Mir140-null mice (KO) compared with Mir140 heterozygous mice (Ctrl). Protein extract isolated from overnight culture of rib chondrocytes (2 mice each genotype) was subjected to Western blot analysis. Signals were quantified by densitometric analysis, normalized by Actin, and expressed relative to Ctrl. (B) MEF2C, but not MEF2D, is upregulated in Mir140-null chondrocytes. Signals were quantified, normalized and expressed relative to Ctrl. (C) Mef2c RNA is upregulated in Mir140-null mice. qRT-PCR was performed using RNA isolated from rib chondrocytes. *p< 0.05, n = 3. (D) MEF2-luciferase assay using primary rib chondrocytes. Cell lysate was prepared for luciferase assay 24 hours after transfection of reporter constructs in the presence of PTH at concentration of 10−9M (PTH-9) and 10−8M (PTH-8). Values of p are indicated. Mir140-null chondrocytes show a modest, but significant, increased MEF2 activity in the presence of PTH. (E, F) Retrovirus-mediated miR-140 overexpression in primary chondrocytes reduces MEF2C expression at the protein (E) and mRNA (F) levels. Primary rib chondrocytes isolated from Mir140−/− mice were infected with viruses expressing miR-140 with GFP (miR-140) or GFP alone (control, GFP). Approximately 60% of cells were infected. Cells were harvested 2 days after infection. Protein expression was quantified, normalized, and expressed relative to control. miR-140 expression was normalized to U6, expressed relative to that of wild-type chondrocytes. ND = not detected. *p < 0.05, n = 3.

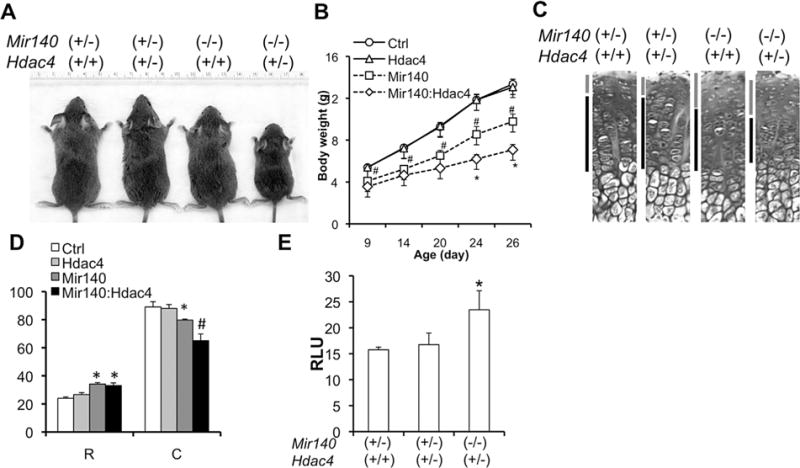

In order to further test whether MEF2C upregulation in Mir140-null mice contributes to premature hypertrophic differentiation, we crossed Mir140-null mice to Hdac4 heterozygous null mice. Hdac4 heterozygous mice showed a normal animal growth, whereas the compound mutant mice, Mir140−/− Hdac4+/−, exhibited a significant growth impairment compared with Mir140-null or control mice (Fig. 4A, B). Mir140−/− Hdac4+/− mice showed shortening of the columnar proliferating chondrocytes, a histological finding similar to that of Mir140−/− PTHrP+/− mice (Fig. 4C, D). As expected, the Mef2 transcriptional activity in primary rib chondrocytes in Mir140−/− Hdac4+/− mice was significantly upregulated compared with control (Mir140+/−) (Fig. 4E). Hdac4 heterozygosity alone showed no effect on Mef2 activity, suggesting that one allele of Hdac4 is sufficient to suppress aberrant MEF2 activation.

Fig. 4.

Hdac4 heterozygosity exacerbates the growth defect of Mir140-null mice. (A) Pictures of 3-week-old littermates with indicated genotypes. (B) Growth curve of mice with indicated genotypes. Ctrl, Mir140+/− Hcac4+/+ (n = 8); HDAC4, Mir140+/− Hdac4+/− (n = 4); Mir140, Mir140−/− Hdac4+/+ (n = 7); Mir140:Hdac4, Mir140−/− Hdac4+/− (n = 10). #p < 0.05 versus Ctrl or Hdac4; *p < 0.05 versus Mir140. (C) H&E stained section of growth plates of the proximal tibia. Bars indicate the resting and columnar regions. (D) Quantification of growth plates of mice with indicated genotypes. Mice were euthanized at P26. The length of the resting zone (R) and the columnar proliferating zone (C) was measured. *p < 0.05 versus Ctrl or HDAC4; #p < 0.05 versus Ctrl, HDAC4, or Mir140; n ≥ 3. (E) Mef2-luciferase assay using primary rib chondrocytes. Mir140:Hdac4 compound mutant showed a significant increase in Mef2 activity, whereas Hdac4 heterozygosity alone had no effect on Mef2 activity.

Mir140-loss increases p38 MAPK signaling

Mef2c is not predicted to be a miR-140 target gene by publicly available computational prediction programs. In addition, our previous attempt to experimentally identify direct miR-140 targets failed to identify Mef2c.(6) Therefore, MEF2C upregulation in Mir140-null chondrocytes is likely caused indirectly by the deregulation of miR-140-target genes.

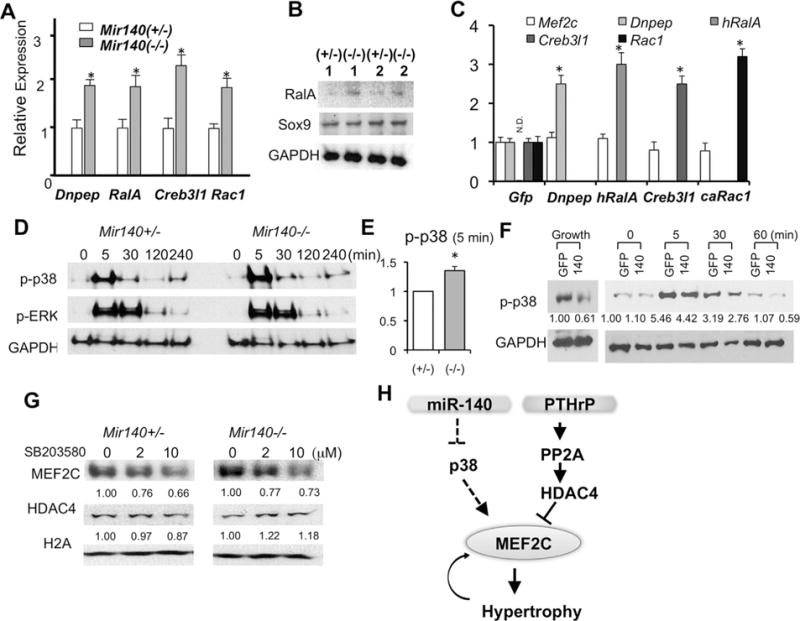

Previous studies identified several direct target genes of miR-140 in various contexts.(5,6,24–28) Among them, we confirmed that Dnpep,(6) RalA,(25) and Creb3l1 (OASIS)(29) were upregulated in Mir140-null chondrocytes (Fig. 5A, B). In addition, we confirmed that Rac1, a predicted miR-140 target, was also upregulated in Mir-140–deficient chondrocytes (Fig. 5A). In a study using human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), miR-140 regulated Sox9 and RalA during chondrocyte differentiation.(25) However, we did not find alteration of Sox9 expression in primary mouse rib chondrocytes missing Mir140 (Fig. 5B). In order to investigate whether upregulation of these miR-140 target genes play a causal role in Mef2c upregulation, we overexpressed Dnpep, Creb3l1, an active form of Rac1, or RalA in wild-type primary rib chondrocytes using a retrovirus expression system. Overexpression of none of these genes increased Mef2c expression, whereas expression of these genes was reasonably upregulated (Fig. 5C). MEF2C activity or expression can be regulated by multiple pathways. p38 MAPKs directly phosphorylate MEF2C and enhance its transcriptional activity to stimulate hypertrophic differentiation.(30) p38 MAPK overactivation in chondrocytes impairs endochondral bone growth in vivo.(31) We found that p38 MAPK signaling was upregulated in miR-140– deficient chondrocytes (Fig. 5D, E). Conversely, miR-140 overexpression in Mir140-null chondrocytes reduced p38 MAPK signaling (Fig. 5F). Inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling decreased MEF2C expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5G). These data suggest that the upregulation of p38 MAPK signaling contributes to the acceleration of hypertrophic differentiation of miR-140–deficient chondrocytes.

Fig. 5.

miR-140 regulate MEF2C expression via the p38 MAPK pathway. (A) Mir140-null chondrocytes show increased Dnpep, RalA, Creb3l1, and Rac1 transcripts. qRT-PCR was performed on primary rib chondrocytes form Mir140+/− and Mir140−/− mice. (B) RalA protein expression is increased in Mir140-null chondrocytes, whereas Sox9 expression is not altered. (C) Overexpression of Dnpep, human RalA (hRalA), Creb3l1, or a constitutively active mutant of Rac1 (caRac1) does not increase Mef2c expression. Gene expression was determined byqRT-PCR 3days after retrovirus infection to overexpress indicated genes. Infected viruses are indicated below the x-axis. Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer achieved twofold to threefold upregulation of indicated genes. Human RalA transcript was not detected in control (GFP) (ND). (D) p38 MAPK signaling is upregulated in Mir140-null chondrocytes. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (p-p38 MAPK) and ERK1/2 (p-ERK) was assessed by immunoblot analysis at indicated time points after serum stimulation. A representative result from three independent experiments using pairs of control and Mir140-null littermates is shown. (E) Quantification of the p-p38 level at the 5-min time point in D. Relative p-p38 levels in Mir140−/− (−/−) and Mir140+/− (+/−) were calculated in three sets of independent experiments. *p < 0.05, n = 3. (F) Retrovirus-mediated miR-140 overexpression reduces basal and stimulated levels of p-p38 MAPK. Mir140-null primary rib chondrocytes were infected with control (GFP) and miR-140-GFP (140) retroviruses and cultured for 2 days. p-p38 levels were determined in a similar fashion as in D. Cell lysates were also prepared from cells cultured in a growth medium without serum starvation (Growth). Signals were quantified, normalized, and expressed relative to control. (G) p38 MAPK inhibition reduces expression of MEF2C in a dose-dependent manner, whereas expression of HDAC4 and Histone 2 A (H2A) is not affected. Cells were cultured for 48 hours in the presence of indicated concentration of SB 203580. Signals were quantified, normalized, and expressed relative to vehicle control. (H) Proposed model. miR-140 enhances the PTHrP/HDAC4 pathway to control hypertrophic differentiation by suppressing premature MEF2C expression, at least in part, through dampening p38 MAPK signaling. ND = not detected.

Discussion

miRNAs are considered to act as genetic buffers to suppress undesired gene expression to maintain the robustness of the gene expression pattern and phenotype of a cell. In this work, we found that the miR-140 pathway interacts with the PTHrP-HDAC4 pathway to control chondrocyte differentiation. PTHrP negatively regulates hypertrophic differentiation, at least in part, by enhancing HDAC4 function. In the presence of miR-140, PTHrP or HDAC4 produced from one allele of these genesis sufficient to maintain normal skeletal growth, and the absence of miR-140 alone causes a modest effect in endochondral growth. Therefore, our observation that PTHrP or Hdac4 heterozygosity causes a substantial growth defectinmiR-140 deficiency is consistent with the idea that the miR-140 buffers the negative impact caused by a partial impairment of the primary regulatory system of chondrocyte differentiation. We previously showed that the mineralization of the talus of neonatal Mir140-null mice is mildly advanced due to accelerated hypertrophic differentiation.(6) In this study, we found that compound mutant mice, Mir140−/− PTHrP+/− or Mir140−/− Hdac4+/−, showed a further increase in mineralization compared with Mir140−/− mice, a result consistent with the data on skeletal growth, although this data needs to be interpreted cautiously because we found that both PTHrP and Hdac4 heterozygosity showed advanced mineralization in this bone in the Mir140 heterozygous background (Supporting Fig. 2A, B).

A previous study showed that PTHrP regulates MEF2C function by facilitating HDAC4 nuclear localization.(13) We found that miR-140 loss increased the expression and function of MEF2C without changing the abundance or phosphorylation of HDAC4. Thus, PTHrP and miR-140 appear to regulate hypertrophic differentiation through independent mechanisms, but nevertheless the PTHrP pathway and miR-140 pathway converge on MEF2C regulation. MEF2 transcription factors drive hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation. Mef2c expression is upregulated in prehypertrophic chondrocytes.(7) This transcriptional upregulation of Mef2c upon chondrocyte differentiation likely creates a positive feedback loop that further accelerates hypertrophic differentiation.

Expression and function of MEF2 transcription factors is controlled by diverse upstream regulatory systems.(32) MAPKs, including p38 MAPKs, are major HDAC-independent regulators of MEF2C.p38 MAPKs phosphorylate MEF2C to augment its function in monocyte/macrophage-like cells,(33) B cells,(34) myoblasts,(35) cardiomyocytes,(36,37) and vascular endothelial cells.(38) In primary chondrocytes, p38 MAPK inhibition reduces MEF2C function and hypertrophic differentiation.(30) On the other hand, overactivation of p38 MAPK,via overexpression of a constitutive form of MKK6, in chondrocytes results in an endochondral bone growth defect and reduces the number of proliferating chondrocytes, suggesting that p38 MAPK signaling induces premature cell cycle exit and hypertrophic differentiation.(31) In light of these reports, it is likely that the upregulation of p38 MAPK signaling in miR-140–deficient chondrocytes, at least in part, contributes to the acceleration of the hypertrophic differentiation; p38 MAPK signaling enhances MEF2C function to promote the hypertrophic differentiation program that further increases MEF2C expression.

The mechanism by which miR-140 deficiency enhances p38 MAPK signaling is currently unclear. Rac1, which was upregulated in miR-140–deficient chondrocytes, regulates chondrocyte differentiation(39–41) and activates p38 MAPK signaling in chondrocytes.(42) However, it is unlikely that Rac1 is responsible for the upregulated p38 MAPK signaling and the phenotype of miR-140–null mice because Rac1 overexpression did not change Mef2c expression.

Based on these findings, we propose a model in which miR-140 enhances the robustness of the PTHrP/HDAC4 axis in controlling hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes by suppressing MEF2C-inducing stimuli. miR-140 suppresses the positive feedback loop in which MEF2C upregulates itself by promoting hypertrophic differentiation (Fig. 5H); this effect is likely mediated, at least in part, by downregulating p38 MAPK signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AR054500 and AR056645 to TK) and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (SG-0090-13 to TK). We thank Dr. Arthur Broadus for Col2-PTHrP transgenic and PTHrP knockout mice, Dr. Eric Olson for Hdac4 knockout mice, and Dr. Ernestina Schipani for Col2-caPPR transgenic mice. We thank Dr. Henry Kronenberg for helpful discussion.

Authors’ roles: GP, FM, TSL, SN, MNW, and TK designed and performed the experiments. TK wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Disclosures

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature. 2003;423(6937):332–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornstein E, Shomron N. Canalization of development by micro-RNAs. Nat Genet. 2006;38(Suppl):S20–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455(7209):64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455(7209):58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyaki S, Sato T, Inoue A, et al. MicroRNA-140 plays dual roles in both cartilage development and homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2010;24(11):1173–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1915510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura Y, Inloes JB, Katagiri T, Kobayashi T. Chondrocyte-specific microRNA-140 regulates endochondral bone development and targets Dnpep to modulate bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(14):3019–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05178-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold MA, Kim Y, Czubryt MP, et al. MEF2C transcription factor controls chondrocyte hypertrophy and bone development. Dev Cell. 2007;12(3):377–89. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clocchiatti A, Di Giorgio E, Demarchi F, Brancolini C. Beside the MEF2 axis: unconventional functions of HDAC4. Cell Signal. 2013;25(1):269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang XJ, Seto E. The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(3):206–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vega RB, Matsuda K, et al. Histone deacetylase 4 controls chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletogenesis. Oh J. 2004;119(4):555–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healy S, Khan DH, Davie JR. Gene expression regulation through 14–3–3 in teractions with histones and HDACs. Discov Med. 2011;11(59):349–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasagawa S, Takemori H, Uebi T, et al. SIK3 is essential for chondrocyte hypertrophy during skeletal development in mice. Development. 2012;139(6):1153–63. doi: 10.1242/dev.072652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozhemyakina E, Cohen T, Yao TP, Lassar AB. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide represses chondrocyte hypertrophy through a protein phosphatase 2A/histone deacetylase 4/MEF2 pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(21):5751–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00415-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paroni G, Cernotta N, Dello Russo C, et al. PP2A regulates HDAC4 nuclear import. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(2):655–67. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Macica CM, Dreyer BE, et al. Initial characterization of PTH-related protein gene-driven lacZ expression in the mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(1):113–123. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13(16):2072–2086. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weir EC, Philbrick WM, Amling M, Neff LA, Baron R, Broadus AE. Targeted overexpression of parathyroid hormone-related peptide in chondrocytes causes chondrodysplasia delayed endochondral bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(19):10240–10245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schipani E, Lanske B, Hunzelman J, et al. Targeted expression of constitutively active receptors for parathyroid hormone, parathyroid hormone-related peptide delays endochondral bone formation, rescues mice that lack parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):13689–13694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod MJ. Differential staining of cartilage and bone in whole mouse fetuses by Alcian blue and Alizarin red S. Teratology. 1980;22(3):299–301. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420220306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sablina AA, Chen W, Arroyo JD, et al. The tumor suppressor PP2A Abeta regulates the RalA GTPase. Cell. 2007;129(5):969–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subauste MC, Von Herrath M, Benard V, et al. Rho family proteins modulate rapid apoptosis induced by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and Fas. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(13):9725–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papaioannou G, Inloes JB, Nakamura Y, Paltrinieri E, Kobayashi T. Let-7 miR-140 microRNAs coordinately regulate skeletal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(35):E3291–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302797110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backs J, Song K, Bezprozvannaya S, Chang S, Olson EN. CaM kinase II selectively signals to histone deacetylase 4 during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1853–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI27438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberhart JK, He X, Swartz ME, et al. MicroRNA Mirn140 modulates Pdgf signaling during palatogenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(3):290–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlsen TA, Jakobsen RB, Mikkelsen TS, Brinchmann JE. MicroRNA-140 targets RALA and regulates chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by translational enhancement of SOX9 and ACAN. Stem Cells Dev. 2014 Feb 1;23(3):290–304. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolas FE, Pais H, Schwach F, et al. MRNA expression profiling reveals conserved and non-conserved miR-140 targets. RNA Biol. 2011;8(4):607–15. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.15390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuddenham L, Wheeler G, Ntounia-Fousara S, et al. The cartilage specific microRNA-140 targets histone deacetylase 4 in mouse cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(17):4214–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R, Ma J, Yao J. Molecular mechanisms of the cartilage-specific microRNA-140 in osteoarthritis. Inflamm Res. 2013;62(10):871–7. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vellanki RN, Zhang L, Guney MA, Rocheleau JV, Gannon M, Volchuk A. OASIS/CREB3L1 induces expression of genes involved in extracellular matrix production but not classical endoplasmic reticulum stress response genes in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151(9):4146–57. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanton LA, Sabari S, Sampaio AV, Underhill TM, Beier F. P38 MAP kinase signalling is required for hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation. Biochem J. 2004;378(Pt 1):53–62. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang R, Murakami S, Coustry F, Wang Y, de Crombrugghe B. Constitutive activation of MKK6 in chondrocytes of transgenic mice inhibits proliferation delays endochondral bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(2):365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development. 2007;134(23):4131–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han J, Jiang Y, Li Z, Kravchenko VV, Ulevitch RJ. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature. 1997;386(6622):296–9. doi: 10.1038/386296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khiem D, Cyster JG, Schwarz JJ, Black BL. A p38 MAPK-MEF2C pathway regulates B-cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(44):17067–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804868105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zetser A, Gredinger E, Bengal E. P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Participation of the Mef2c transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(8):5193–200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolodziejczyk SM, Wang L, Balazsi K, DeRepentigny Y, Kothary R, Megeney LA. MEF2 is upregulated during cardiac hypertrophy and is required for normal post-natal growth of the myocardium. Curr Biol. 1999;9(20):1203–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Boerm M, McCarty M, et al. Mekk3 is essential for early embryonic cardiovascular development. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):309–13. doi: 10.1038/73550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maiti D, Xu Z, Duh EJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces MEF2C and MEF2-dependent activity in endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(8):3640–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerr BA, Otani T, Koyama E, Freeman TA, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Small GTPase protein Rac-1 is activated with maturation and regulates cell morphology and function in chondrocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(6):1301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woods A, Wang G, Dupuis H, Shao Z, Beier F. Rac1 signaling stimulates N-cadherin expression, mesenchymal condensation, and chondrogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(32):23500–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Woods A, Agoston H, Ulici V, Glogauer M, Beier F. Genetic ablation of Rac1 in cartilage results in chondrodysplasia. Dev Biol. 2007;306(2):612–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang G, Beier F. Rac1/Cdc42 and RhoA GTPases antagonistically regulate chondrocyte proliferation, hypertrophy, and apoptosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(6):1022–31. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]