Abstract

Objectives

We assessed preferences of social media-using young black, Hispanic and white men-who-have-sex-with-men (YMSM) for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing, as compared with other currently available HIV testing options. We also identified aspects of the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test that might influence preferences for using this test instead of other HIV testing options and determined if consideration of HIV testing costs and the potential future availability of fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing change HIV testing preferences.

Study design

Anonymous online survey.

Methods

HIV-uninfected YMSM across the United States recruited from multiple social media platforms completed an online survey about willingness to use, opinions about and their preferences for using oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing and five other currently available HIV testing options. In a pre/post questionnaire format design, participants first indicated their preferences for using the six HIV testing options (pre) before answering questions that asked their experience with and opinions about HIV testing. Although not revealed to participants and not apparent in the phrasing of the questions or responses, the opinion questions concerned aspects of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing (e.g. its possible advantages/disadvantages, merits/demerits, and barriers/facilitators). Afterward, participants were queried again about their HIV testing preferences (post). After completing these questions, participants were asked to re-indicate their HIV testing preferences when considering they had to pay for HIV testing and if fingerstick blood sample rapid HIV self-testing were an additional testing option. Aspects about the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test associated with influencing increased the preference for using the test (post assessment vs pre-assessment of opinion topics) were identified through multivariable regression models that adjusted for participant characteristics.

Results

Of the 1975 YMSM participants, the median age was 22 years (IQR 20–23); 19% were black, 36% Hispanic, and 45% white; and 18% previously used an oral fluid rapid HIV self-test. Although views about oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing test were favorable, few intended to use the test. Aspects about the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test associated with an increased preference for using the test were its privacy features, that it motivated getting tested more often or as soon as possible, and that it conferred feelings of more control over one’s sexual health. Preferences for the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test were lower when costs were considered, yet these YMSM were much more interested in fingerstick blood sampling than oral fluid sampling rapid HIV self-testing.

Conclusions

Despite the perceived advantages of the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test and favorable views about it by this population, prior use as well as future intention in using the test were low. Aspects about oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing identified as influential in this study might assist in interventions aimed to increase its use among this high HIV risk population as a means of encouraging regular HIV testing, identifying HIV-infected persons, and linking them to care. Although not yet commercially available in the United States, fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing might help motivate YMSM to be tested more than oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing.

Keywords: HIV, Internet, Young adult, Homosexuality, Surveys and questionnaires, Cross-sectional studies

Introduction

In the United States (US), black, Hispanic, and white young (18–24 year-old) men-who-have-sex-with-men (YMSM) are disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic,1–6 as exhibited by increasing HIV incidence rates,1, 5, 7, 8 high HIV prevalence, andhighlevels of undiagnosed HIV infections2, 8–10 among this population. Although HIV testing rates appear to be improving among YMSM, they are relatively lower than for other MSM, which limits their chances of receiving appropriate treatment and impedes efforts to reduce the occurrence of new infections among their sexual or injection drug-using contacts.2, 8, 11, 12 Barriers such as lack of access to and availability of testing centers, healthcare insurance, medical providers, and transportation options; as well as concerns about confidentiality might prevent some YMSM from being tested at medical facilities and community organizations.13

Despite obviating some of the concerns and inconveniences of traditional venue-based HIV testing, the sole commercially available home-based conventional (i.e. non-rapid) mail-in blood sample collection HIV test (Home Access® HIV-1 Test System, Home Access Health, Hoffman Estates, IL) available in the US is used infrequently by MSM.14 A major limitation of this test is that users must collect a blood sample on a gauze pad, mail it to the testing center, and then telephone the laboratory several days later before obtaining the results.13, 15, 16 The cost of testing also might be a barrier to its use. Given the lower than critically needed testing rates observed among black, Hispanic and white YMSM in the US and the limits of current testing options, other means of increasing HIV testing appear to be necessary.

In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the OraQuick® In–home rapid HIV test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA) for oral fluid self-testing as an over-the-counter test.17 A prime motivation for the oral fluid HIV self-test has been to increase the availability and convenience of HIV testing. The test is provided in a kit with step-by-step instructions on how to obtain the oral fluid sample, conduct the test, and read the results. The company provides free telephone-based assistance to those with queries about conducting the test, interpreting the results, and how and where to seek help if concerns arise or the test result is positive. The OraQuick® In–home rapid HIV test is a re-packaging of the company’s oral fluid rapid HIV test (current version is the OraQuick® ADVANCE rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test) which is performed by a clinician or other test provider. The company’s original oral fluid rapid HIV test became commercially available in the US in 2004 and subsequent iterations of the test have been used in clinical, nonclinical, and community outreach testing. Per the manufacturer’s package insert information, the OraQuick® In–home rapid HIV test sensitivity is 91.7% and specificity is 99.9%,18 whereas the OraQuick® ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test sensitivity is 99.3% and specificity is 99.8%19 (although some post marketing studies have reported lower values).20 In addition to this commercially available oral fluid rapid HIV self-test, over-the-counter fingerstick blood sample rapid HIV self-tests are under consideration for home-based use, although they are not yet offered in the US.21

Because the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test is widely accessible for purchase in stores or via the internet in the US, is considered easy to use, involves an oral swab instead of a blood sample, is private, and provides test results within 20 min, it is possible that this testing method might be employed in public health outreach campaigns to increase testing utilization among black, Hispanic, and white YMSM. Before such potentially costly public health approaches can be recommended, it is crucial first to assess YMSM willingness to use oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing as compared with other currently readily available HIV testing options. Given the widespread popularity among and the ubiquity of social media outlets for this population, it would be particularly useful to measure willingness to use the test among social media users, since these venues could be used to access this hard-to-reach population quickly and confidentially. Although prior research indicates interest by MSM in using the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test,22 it is more revealing to gauge testing preferences in context to the myriad of testing choices available to YMSM. YMSM might indicate they are interested in the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test, but when asked which test they would actually use, they might choose another testing option. In such a scenario, distributing the tests to YMSM in community outreach campaigns might not increase testing more than encouraging these men to use other HIV testing options. It also would be helpful to know which factors (e.g. demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, sexual HIV risk-taking behaviors, and aspects about oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing) might influence YMSM willingness to use the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test over other HIV testing options. Such factors could be incorporated into the design of interventions aimed to increase oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing among this high HIV risk population.

The primary objective of this investigation was to assess the extent to which social media-using black, Hispanic, and white YMSM are willing to use oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing, as compared with other readily available HIV testing options (testing at medical facilities or community organizations and home-based mail-in blood sample collection HIV testing). The secondary objective was to identify factors that influence willingness to use the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test, as compared with other HIV testing options. We also examined if consideration of the costs of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing and if the potential future availability of fingerstick blood sample rapid HIV self-test influence testing preferences.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study involved an anonymous, internet-based survey of social media-using black, Hispanic, and white YMSM across the US from August–December 2014. Participants answered questions about their demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and injection-drug and sexual HIV risk-taking behaviors followed by the main study questionnaire about HIV testing preferences and opinions. To avoid influencing responses, participants were not informed, and no part of the questionnaire revealed, that the ultimate intent of the study was to compare oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing to other testing options. The hospital’s institutional review board approved the study.

Participant recruitment

YMSM were solicited to participate through multiple social media platforms (See Supplemental Material for platform descriptions and participant solicitation methods). Recruitment occurred through banner or ‘pop-up’ advertisements or emails, and through referrals by other study participants. We followed recommended techniques23 to reduce fraudulent recruitment. YMSM who accessed the study website first completed a brief screening questionnaire to assess study eligibility criteria, which were: 18–24-years-old; English- or Spanish-speaking; black, Hispanic or white; living in the US; ever having had anal sex with another man; and not being HIV infected (per self-report). We offered a lottery for a limited number of $100 gift cards to an online store as an incentive for study participation. Based on the results from prior studies among MSM24–29 examining HIV test acceptance, our target sample size for this study was 1350 (450 black, 450 Hispanic, 450 white participants), to determine if there was at least a 10% greater willingness to undergo oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing than home-based conventional mail-in blood sample collection, medical facility, or community organization testing within and across racial/ethnic groups (α = 0.05, power 0.80).

Study questionnaire development and content

The study authors based the study instrument content on their and other published studies and questionnaires related to the study topic. English- and Spanish-language versions were created. Spanish translation was verified through back-translation techniques and review by native Spanish-speaking research team members. Five black, six Hispanic, and six white YMSM were recruited through social media for cognitive-based testing and pilot testing of the study instruments. These evaluations consisted of assessing participant comprehension of survey format, instructions, questions, and responses; soliciting feedback about the study instrument; ensuring its cultural and age appropriateness for black, Hispanic, and white YMSM; and verifying that it was interesting, engaging, and functioning properly across computer operating systems via the internet.23, 30 Participants were interviewed via telephone while they completed the study instruments. The questionnaire was revised in an iterative fashion based on their feedback and the cognitive-based and pilot testing results (See Supplemental Material for an English-language copy of the study instrument).

The main study questionnaire consisted of six sections. At the start of section one, participants were provided a brief description of the six HIV testing options (medical facility testing [rapid or conventional], community organization testing [rapid or conventional], home-based conventional mail-in blood sample collection HIV testing, and oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing). Participants could refer to a chart of these descriptions while completing the questionnaire. Sections one and four contained identical sets of six questions intended to capture participant preferences about the six HIV testing options. In sections one and four, participants indicated which of the six HIV testing options they would:1 most or least likely undergo for their next HIV test,2 most or least likely recommend to others,3 choose for their next HIV test, and4 want if they were concerned they might be HIV infected. Participants were asked to respond to the questions in sections one and four if the cost of HIV testing was not a factor in their testing preferences. They also were asked to provide the main reasons for their preferences. The purpose of section one was to measure participant HIV testing preferences before (‘pre’) they considered the topics asked about in sections two and three. The purpose of section four was to measure HIV testing preferences after (‘post’) participants answered the questions in sections two and three.

Section two queried participants about their prior experiences with using each of the six HIV testing options. Section three contained thirteen questions designed to elicit opinions about the six HIV testing options. The questions in reality concerned aspects about oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in regards to its possible advantages/disadvantages, merits/demerits, and barriers/facilitators to its use. These aspects were derived from prior published research on oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing (ease of obtaining testing; comprehension of test results; facilitation of medical care after a positive HIV test; access to HIV counseling; embarrassment about testing; anxiety about testing; privacy in testing; testing accuracy; privacy in receiving test results; motivation to be tested more often; motivation to be tested sooner; control over sexual health; and motivation to encourage sexual partners to be tested). However, it was not revealed to participants and not apparent in the phrasing of the questions or responses that they were being queried about their opinions on positive or negative aspects of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing. Instead, the format of the questions asked participants their opinions on which of the six HIV testing options had the most desired (e.g. ease of obtaining) or least desired (e.g. embarrassment about testing) characteristic.

In section five of the survey, participants were asked to select their HIV testing preferences if they had to pay for testing. In section six, they were asked to indicate their HIV testing preferences if fingerstick blood sample rapid HIV self-test was available as an additional HIV testing option.

Data analysis

Recruitment, enrollment, and retention were summarized, and participants were compared by enrollment and retention status using summary statistics. Responses to the demographic characteristics, HIV testing and HIV risk-taking questions, and main study questionnaire were summarized. For the primary objective comparing oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing to the other five available HIV testing options, responses to the HIV testing preferences questions ‘pre’ (survey section one) and ‘post’ (section four) were summarized. Differences in responses (post vs pre) were calculated along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For the secondary objective, we measured increases in preferences for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing vs all other HIV testing options in two ways: increases in preference for the test (i.e. viewing the test more positively) and decreases in lack of preference for the test (i.e. viewing the test less negatively). First, we measured how frequently participants changed from preferring an HIV test other than oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in the ‘pre’ (section one) HIV testing options preferences questions to preferring oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in the ‘post’ (section four) questions. Four aspects of increases in preferences for oral fluid rapid HIV testing were assessed: next HIV test most likely to receive, HIV test most likely to recommend to others, which HIV test would choose for next test, and test would get if worried about being infected with HIV. Second, we measured how frequently participants changed from selecting oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in the ‘pre’ (section one) questions as the next HIV test least likely to receive or the HIV test least likely to recommend to others in the ‘post’ (section two) HIV testing options preferences questions. Afterward, we constructed univariable logistic regression models to identify factors (demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, HIV risk-taking behaviors, and aspects about oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing queried about in the thirteen HIV testing opinions questions) associated with changes in preferences for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing as compared with all other HIV testing options. For these models, we only used the discordant pairs data; i.e. participants who changed their preferences from ‘pre’ to ‘post’ for these models, because the concordant pairs data (no change in preferences from ‘pre’ to ‘post’) provided no additional information. Covariates significant at the α = 0.05 level in univariable models were considered further in multivari-able logistic regression models. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs were estimated.

For the analysis examining how consideration of the costs of HIV testing might impact HIV testing preferences, we first summarized the responses in survey section five asking participants which HIV test they would most likely choose if they had to pay for HIV testing, and which test they were least likely to choose. Next, we compared participant HIV testing option preferences when considering the costs of HIV testing (section five) vs their HIV testing option preferences in the ‘post’ (section four) questions. We calculated proportions and accompanying 95% CIs who changed (e.g. proportions who preferred oral fluid rapid HIV testing when considering the costs of HIV testing in section five but chose another HIV testing option in section four) or did not change their preferences. The analysis examining how the addition of fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing affected HIV testing preferences was performed in a similar manner.

Results

Participant characteristics

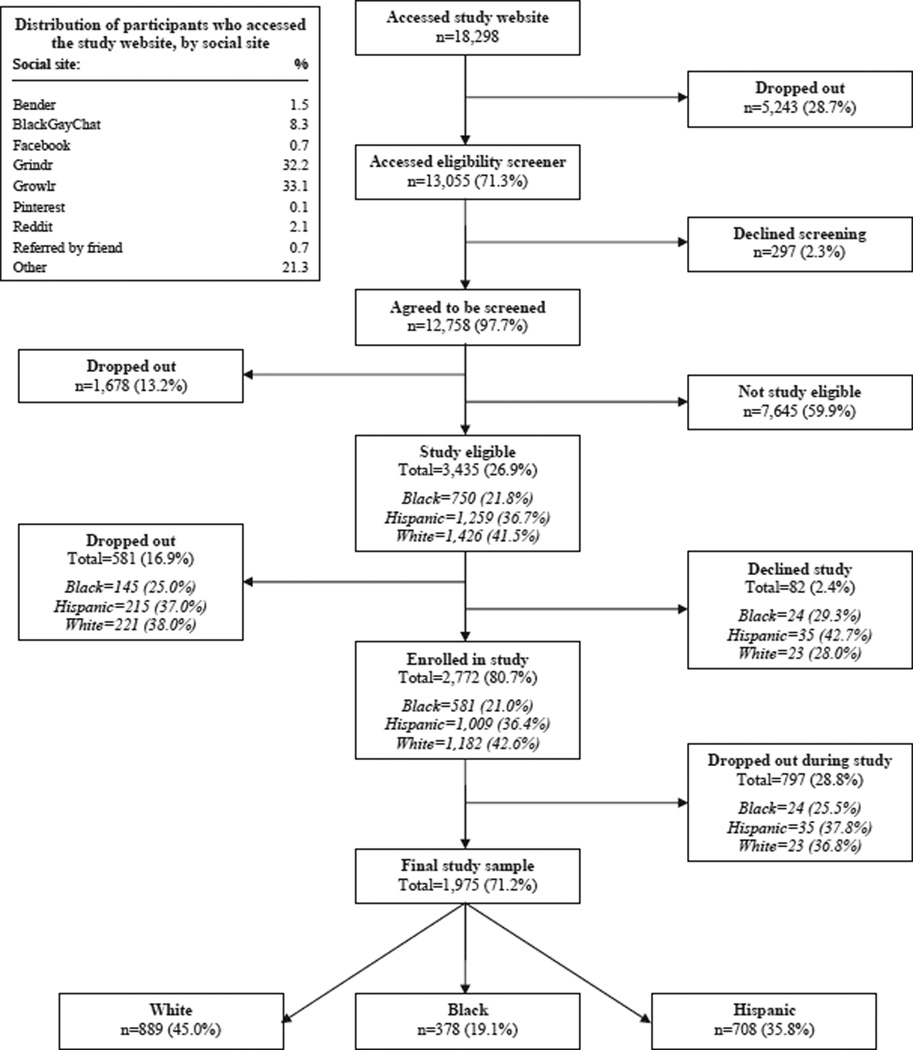

Of the 1975 YMSM participants (Fig. 1), the median age was 22 years (IQR 20–23); 19% were black, 36% Hispanic, and 45% white; 70% had a primary health care provider or clinic; and 76% were covered by health care insurance. Few had ever injected drugs (2%), the majority had condom-less anal sex with another man within the past six months (64%), and many reported having had two or more casual condom-less insertive (40%) or receptive (41%) anal sex partners. Most had been tested for HIV (89%). Among the 1619 ever tested for HIV, a majority (62%) had a conventional HIV test at a medical facility. Although 51% reported previously having a rapid HIV test at a community organization, only 18% previously had an oral fluid rapid HIV self-test. Few (6%) had used a home-based conventional mail-in blood sample collection HIV test, and those who had gave it a lower testing experience rating (mean 7.6 on a 10-point scale) than those who had used the other HIV tests (See the Supplemental Material for additional descriptions of the participants and their enrollment; comparisons of those study eligible vs not study eligible, who enrolled vs did not enroll, and who were in the final study sample vs who dropped out; and their HIV testing, injection-drug use, and HIV sexual risk-taking histories.).

Fig. 1.

Participant enrollment.

HIV testing options preferences pre- and post assessment of HIV testing experiences and opinions

In the ‘pre’ (section one) HIV testing options preferences questions (before being asked about HIV testing experiences and opinions in sections two and three), most YMSM expected that their next HIV test would be at a medical facility (47%) or a community organization (30%; Table 1). Fewer than 25% would choose conventional or home-based testing for their next test. In addition, more participants indicated that they would recommend medical facility (42%) or community organization (32%) testing to others than either type of currently available home-based HIV testing (15%). Of interest, more YMSM would choose conventional HIV testing at a medical facility (44%) than all other testing, if concerned about being HIV infected.

Table 1.

Participant HIV testing preferences, pre/post HIV testing experiences and opinions assessment.

| HIV testing preferences | n = 1975 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre |

Post |

Post–pre D |

|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | Δ% (95% CI) | |

| Next HIV test most likely to receive | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 10.0 (8.7, 11.3) | 8.6 (7.4, 9.8) | − 1.4 (−3.2, 0.4) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 19.6 (17.8, 21.3) | 19.9 (18.1, 21.7) | 0.3 (−2.2, 2.8) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 34.5 (32.4, 36.6) | 31.6 (29.6, 33.7) | −2.8 (−5.8, 0.1) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 12.0 (10.6, 13.4) | 11.7 (10.3, 13.1) | −0.3 (−2.3, 1.7) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 3.0 (2.2, 3.7) | 3.1 (2.4, 3.9) | 0.2 (−0.9, 1.2) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 14.9 (13.3, 16.5) | 21.6 (19.8, 23.4) | 6.7 (4.3, 9.1) |

| Don’t know | 5.9 (4.9, 7.0) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.1) | −2.6 (−3.9, −1.3) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.1) |

| Next HIV test least likely to receive | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 15.1 (13.6, 16.7) | 18.7 (17.0, 20.5) | 3.6 (1.3, 5.9) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 5.8 (4.7, 6.8) | 6.6 (5.5, 7.7) | 0.8 (−0.7, 2.3) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 11.6 (10.2, 13.0) | 13.9 (12.3, 15.4) | 2.3 (0.2, 4.4) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 3.1 (2.3, 3.9) | 3.1 (2.4, 3.9) | 0.1 (−1.0, 1.1) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 23.1 (21.3, 25.0) | 21.8 (20.0, 23.6) | − 1.4 (−4.0, 1.2) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 27.0 (25.1, 29.0) | 26.1 (24.1, 28.0) | − 1.0 (−3.7, 1.8) |

| Don’t know | 14.1 (12.5, 15.6) | 9.7 (8.4, 11.0) | −4.4 (−6.4, −2.3) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.2 (0.0, 0.3) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.2) |

| HIV test most likely to recommend to others | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 11.5 (10.1, 12.9) | 9.9 (8.6, 11.2) | − 1.6 (−3.5, 0.3) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 20.1 (18.3, 21.8) | 21.9 (20.1, 23.7) | 1.9 (−0.7, 4.4) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 33.9 (31.8, 36.0) | 29.4 (27.4, 31.4) | −4.5 (−7.4, −1.6) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 12.6 (11.1, 14.0) | 11.1 (9.8, 12.5) | −1.4 (−3.4, 0.6) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.4) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.2) | 0.7 (−0.2, 1.6) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 12.8 (11.3, 14.2) | 18.9 (17.2, 20.6) | 6.1 (3.9, 8.4) |

| Don’t know | 7.3 (6.1, 8.4) | 6.2 (5.1, 7.2) | − 1.1 (−2.7, 0.4) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) |

| HIV test least likely to recommend to others | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 10.5 (9.2, 11.9) | 13.4 (11.9, 14.9) | 2.9 (0.9, 4.9) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 5.4 (4.4, 6.4) | 6.9 (5.8, 8.0) | 1.5 (0.0, 3.0) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 7.7 (6.6, 8.9) | 9.3 (8.0, 10.5) | 1.5 (−0.2, 3.3) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 2.1 (1.5, 2.8) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.1) | 1.2 (0.2, 2.2) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 18.9 (17.2, 20.7) | 19.6 (17.9, 21.4) | 0.7 (−1.8, 3.2) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 30.2 (28.2, 32.2) | 26.8 (24.9, 28.8) | −3.3 (−6.2, −0.5) |

| Don’t know | 24.7 (22.8, 26.6) | 20.0 (18.2, 21.8) | −4.7 (−7.3, −2.1) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.4 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.0) | 0.3 (−0.1, 0.7) |

| Which HIV test would choose for next test | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 9.1 (7.8, 10.3) | 7.0 (5.9, 8.2) | −2.0 (−3.7, −0.3) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 11.9 (10.5, 13.3) | 13.3 (11.8, 14.8) | 1.4 (−0.7, 3.4) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 36.8 (34.6, 38.9) | 35.3 (33.2, 37.4) | − 1.5 (−4.5, 1.5) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 15.2 (13.7, 16.8) | 13.3 (11.8, 14.8) | −2.0 (−4.2, 0.2) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 4.2 (3.3, 5.1) | 3.1 (2.4, 3.9) | − 1.1 (−2.2, 0.1) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 18.9 (17.2, 20.7) | 24.6 (22.7, 26.5) | 5.6 (3.1, 8.2) |

| Don’t know | 3.8 (3.0, 4.6) | 3.2 (2.5, 4.0) | −0.6 (−1.7, 0.6) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) |

| Test would get if concerned about being infected with HIV | |||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test | 7.4 (6.2, 8.5) | 8.6 (7.4, 9.8) | 1.2 (−0.5, 2.9) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test | 7.4 (6.3, 8.6) | 9.5 (8.2, 10.8) | 2.0 (0.3, 3.8) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test | 43.5 (41.4, 45.7) | 43.2 (41.1, 45.4) | −0.3 (−3.4, 2.8) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test | 20.8 (19.0, 22.5) | 19.3 (17.6, 21.0) | − 1.5 (−4.0, 1.0) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) | 3.4 (2.6, 4.2) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.2) | −1.7 (−2.7, −0.7) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) | 13.2 (11.7, 14.7) | 13.7 (12.2, 15.2) | 0.5 (−1.6, 2.6) |

| Don’t know | 4.2 (3.3, 5.0) | 3.9 (3.0, 4.8) | −0.3 (−1.5, 1.0) |

| Refuse to answer | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

After answering the questions about HIV testing experiences and opinions (survey sections two and three), modest proportions (5–6%) of YMSM indicated increased interest (post vs pre HIV testing preferences) in home-based oral rapid HIV self-testing as the test they would most likely receive next, recommend to others, and choose for their next test (Table 1). When comparing post vs pre HIV testing preferences responses, 3% were less likely to select oral rapid HIV self-testing as the test they would least likely recommend to others (i.e. viewed it less negatively). There were no changes in preferences for the remaining questions. The most common reasons participants cited for choosing the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test as their next test were related to its privacy, convenience, and speed; common reasons for not choosing this method were concerns about its accuracy, testing by oneself alone, and preferring that a professional conduct testing (See Supplemental Material).

Factors associated with greater/lesser preference for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing

In nine of the thirteen opinion questions in survey section three, higher proportions of YMSM indicated that they believed oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing was the easiest (27%) and least embarrassing to get (47%); caused the least anxiety about getting HIV tested (36%); offered the most privacy in getting tested (58%) and obtaining test results (55%); motivated getting tested more often (30%) and as soon as possible (34%) as well as having their sexual partner tested (32%); and gave them a feeling of being more in control over their sexual health (31%). In the four remaining opinion questions, fewer YMSM considered oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing to be the easiest in understanding test results (15%), the easiest way to get medical care if their HIV test was positive (3%), the easiest to talk to a test counselor about test results (3%), or the most accurate HIV test (2%). Medical facility conventional HIV testing was favored in all of those situations.

Four opinions prevailed in the multivariable logistic regression models as being associated with viewing oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing more favorably as compared to the other HIV testing options (post [section four] vs pre [section one] HIV testing preferences responses): privacy in getting tested, motivation to get tested more often, motivation to get tested as soon as possible, and feeling more in control over their sexual health (Table 2). In regards to viewing the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test less negatively, three opinions were associated with reductions (post vs pre) in unfavorable views: privacy in getting the test results, motivation to be tested as soon as possible, and motivation to get sexual partners tested. No other HIV testing opinions were associated with changes in preferences regarding the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test. (See Supplemental Material for additional details about participant HIV testing opinions and the univariable analyses results for demographic characteristics (including race/ethnicity), participant HIV testing history or experiences, and sexual or injection drug use history elements.)

Table 2.

Aspects motivating change in preference for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testingdmultivariable logistic regression analysis results.

| Change in preferences from another HIV test to oral fluid rapid HIV self-test pre-HIV testing options preferences selection: did not choose oral fluid rapid HIV self-test post-HIV testing options preferences selection: chose oral fluid rapid HIV self-test |

Change in lack of preference from oral fluid rapid HIV self-test to another HIV test pre-HIV testing options preferences selection: chose oral fluid rapid HIV self-test post-HIV testing options preferences selection: did not choose oral fluid rapid HIV self-test |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains of HIV test option preferences |

Next HIV test most likely to receivea |

HIV test most likely to recommend to others |

Which HIV test would choose for next testb |

Test would get if concerned about being infected with HIVc |

Next HIV test least likely to received |

HIV test least likely to recommend to otherse |

| Changes in preference pre to Post |

Another HIV test (pre) → Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (post) |

Another HIV test (pre) → Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (post) |

Another HIV test (pre) → Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (post) |

Another HIV test (pre) → Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (post) |

Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (pre) → Another HIV test (post) |

Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (pre) → Another HIV test (post) |

| n = 227 |

n = 235 |

n = 267 |

n = 292 |

n = 403 |

n = 382 |

|

| Aspects of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing motivating change in HIV testing preferences |

OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Offers the most privacy in getting tested | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 3.30 (1.43, 7.63) | |||||

| Another HIV test | Ref | |||||

| Offers the most privacy in getting test results | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 1.77 (1.14, 2.77) | |||||

| Another HIV test | Ref | |||||

| Motivates you to get tested more often | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 4.94 (2.41, 10.13) | |||||

| Another HIV test | Ref | |||||

| Motivates you to get tested as soon as possible | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 2.82 (1.26, 6.32) | 2.63 (1.60, 4.32) | 1.77 (1.05, 2.98) | |||

| Another HIV test | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Makes you feel you have control over your sexual health | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 2.08 (0.94, 4.62) | 2.36 (1.17, 4.78) | 3.92 (2.22, 6.93) | |||

| Another HIV test | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Motivates you to get your sexual partner tested | ||||||

| Oral fluid rapid HIV self-test | 1.89 (1.08, 3.29) | |||||

| Another HIV test | Ref | |||||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio, CI, confidence interval, Ref, reference group.

Note: sample sizes are determined by the number of participants who changed their preference for OraQuick® between the pre-survey and post-survey questions (i.e. the participant chose OraQuick® for pre and did not choose OraQuick® for post, or did not choose OraQuick® for pre and chose OraQuick® for post).

Next HIV test most likely to receive: additionally adjusted for the number of casual male sex partners without condoms (bottom) and experience with the rapid HIV test at a community organization.

Which HIV test would choose for next test: additionally adjusted for living alone and the number of exchange male sex partners without condoms (top).

Test would get if concerned about being infected with HIV: additionally adjusted for chance of being infected with HIV, history of any HIV test, number of casual male sex partners without condoms (bottom), total number of sex partners without condoms (top), and experience with the rapid HIV test at a community organization.

Next HIV test least likely to receive: additionally adjusted for primary health care provider/clinic status, history of any HIV test, and experience with the rapid HIV test at home.

HIV test least likely to recommend to others: additionally adjusted for living alone, chance of being infected with HIV, and the total number of male sex partners without condoms (bottom).

HIV testing options preferences when considering the costs of HIV testing or if fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing were an additional option

When asked to consider the costs of HIV testing, 56% of participants again chose the rapid HIV self-test as their next test, whereas 14% would change to testing at a medical facility and 25% at a community organization (conventional or rapid). Community organization testing had the least change when cost was a factor (Table 3). Common reasons cited for not wanting to use the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test were its expense and concerns about its accuracy (See Supplemental Material). YMSM favored fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing as compared with all other HIV testing options and other home-based tests; 40% who initially chose conventional home-based testing and 56% who chose oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing indicated they would change to this not yet commercially available test (Table 4). Common reasons cited for choosing the fingerstick test were its accuracy, quick speed, use of blood, and convenience (See Supplemental Material).

Table 3.

Participant HIV testing preferences if having to pay for HIV testing and comparison to testing preferences if not having to pay for HIV testing.

| HIV testing preferences |

Total | Community organization: conventional HIV test |

Community organization: rapid HIV test |

Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) |

Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) |

Don’t know | Refuse to answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| HIV test most likely chosen if had to pay for HIV testing |

1975 | 14.8 (13.3, 16.4) | 21.3 (19.5, 23.1) | 25.8 (23.9, 27.8) | 9.0 (7.7, 10.3) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.1) | 21.4 (19.6, 23.2) | 4.2 (3.3, 5.0) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.5) |

| HIV test least likely chosen if had to pay for HIV testing |

1975 | 10.3 (9.0, 11.7) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.2) | 21.7 (19.9, 23.5) | 6.0 (4.9, 7.0) | 22.1 (20.2, 23.9) | 23.6 (21.7, 25.5) | 11.7 (10.3, 13.1) | 0.4 (0.1, 0.6) |

|

HIV test most likely chosen if had to pay for HIV testing (section five HIV testing preferences selection) |

|||||||||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test |

Community organization: rapid HIV test |

Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) |

Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) |

Don’t know | Refuse to answer | ||

| Which HIV test would choose for next test if not paying for HIV testing (section four or ‘post’ HIV testing preferences selection) |

Total | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) |

| Community organization: conventional HIV test |

139 | 61.9 (53.8, 69.9) | 6.5 (2.4, 10.6) | 18.7 (12.2, 25.2) | 1.4 (−0.5, 3.4) | 2.2 (−0.3, 4.6) | 6.5 (2.4, 10.6) | 2.9 (0.1, 5.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test |

262 | 5.7 (2.9, 8.5) | 60.3 (54.4, 66.2) | 12.6 (8.6, 16.6) | 8.0 (4.7, 11.3) | 1.5 (0.0, 3.0) | 9.9 (6.3, 13.5) | 1.9 (0.3, 3.6) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

697 | 18.2 (15.4, 21.1) | 11.5 (9.1, 13.8) | 52.8 (49.1, 56.5) | 2.9 (1.6, 4.1) | 2.4 (1.3, 3.6) | 10.5 (8.2, 12.7) | 1.6 (0.7, 2.5) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4) |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

262 | 5.0 (2.3, 7.6) | 30.2 (24.6, 35.7) | 10.3 (6.6, 14.0) | 38.5 (32.7, 44.4) | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | 11.8 (7.9, 15.7) | 3.4 (1.2, 5.6) | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) |

| Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express) |

62 | 19.4 (9.5, 29.2) | 9.7 (2.3, 17) | 17.7 (8.2, 27.3) | 3.2 (−1.2, 7.6) | 40.3 (28.1, 52.5) | 6.5 (0.3, 12.6) | 3.2 (−1.2, 7.6) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick) |

485 | 7.4 (5.1, 9.8) | 17.5 (14.1, 20.9) | 8.0 (5.6, 10.5) | 6.4 (4.2, 8.6) | 2.3 (0.9, 3.6) | 55.7 (51.2, 60.1) | 2.5 (1.1, 3.9) | 0.2 (−0.2, 0.6) |

| Don’t know | 64 | 6.3 (0.3, 12.2) | 4.7 (−0.5, 9.9) | 9.4 (2.2, 16.5) | 1.6 (−1.5, 4.6) | 6.3 (0.3, 12.2) | 14.1 (5.5, 22.6) | 57.8 (45.7, 69.9) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) |

| Refuse to answer | 4 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 50.0 (1.0, 99.0) | 50.0 (1.0, 99.0) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Participant preferences if fingerstick in-home HIV testing were commercially available and comparison to testing preferences if fingerstick HIV self-testing were not available.

| HIV testing preferences |

Total | Community organization: conventional HIV test |

Community organization: rapid HIV test |

Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

Home: conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) |

Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self-test (OraQuick®) |

Home: rapid HIV test (Fingerstick rapid HIV self-test) |

Don’t want to be tested at home |

Don’t know |

Refuse to answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||

| HIV test most likely would want to have |

1962 | 5.9 (4.9, 7.0) | 11.7 (10.3, 13.1) | 24.0 (22.1, 25.9) | 7.8 (6.7, 9.0) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 11.2 (9.8, 12.6) | 33.2 (31.1, 35.3) | N/A | 4.1 (3.2, 5.0) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.5) |

| HIV test least likely would want to have |

1955 | 14.1 (12.5, 15.6) | 6.3 (5.3, 7.4) | 11.9 (10.4, 13.3) | 4.1 (3.2, 5.0) | 17.3 (15.7, 19.0) | 15.7 (14.0, 17.3) | 16.0 (14.4, 17.6) | N/A | 14.0 (12.5, 15.6) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.0) |

| HIV test most likely would use at home |

1948 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12.7 (11.3, 14.2) | 27.5 (25.5, 29.5) | 49.1 (46.9, 51.3) | 6.1 (5.0, 7.1) | 4.3 (3.4, 5.2) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) |

|

HIV test most likely would want to have (if fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing were available) |

|||||||||||

| Community organization: conventional HIV test |

Community organization: rapid HIV test |

Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

Home: Conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) |

Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self- test (OraQuick®) |

Home: rapid HIV test (Fingerstick rapid HIV self-test) |

Don’t know | Refuse to answer |

|||

| Which HIV test would choose for next test (if fingerstick rapid HIV self- testing were not available) |

Total | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |

| Community organization: Conventional HIV test |

138 | 55.1 (46.8, 63.4) | 6.5 (2.4, 10.6) | 13.8 (8.0, 19.5) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 1.4 (−0.5, 3.4) | 3.6 (0.5, 6.7) | 14.5 (8.6, 20.4) | 5.1 (1.4, 8.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Community organization: rapid HIV test |

259 | 3.1 (1.0, 5.2) | 59.5 (53.5, 65.4) | 3.9 (1.5, 6.2) | 3.5 (1.2, 5.7) | 1.2 (−0.1, 2.5) | 1.5 (0.0, 3.0) | 23.9 (18.7, 29.1) | 3.1 (1.0, 5.2) | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | |

| Medical facility: conventional HIV test |

694 | 2.9 (1.6, 4.1) | 4.3 (2.8, 5.8) | 57.8 (54.1, 61.5) | 2.9 (1.6, 4.1) | 1.7 (0.8, 2.7) | 3.2 (1.9, 4.5) | 25.1 (21.8, 28.3) | 1.7 (0.8, 2.7) | 0.4 (−0.1, 0.9) | |

| Medical facility: rapid HIV test |

258 | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | 7.0 (3.9, 10.1) | 7.8 (4.5, 11.0) | 44.2 (38.1, 50.2) | 0.4 (−0.4, 1.1) | 5.8 (3.0, 8.7) | 32.2 (26.5, 37.9) | 2.3 (0.5, 4.2) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Home: Conventional HIV test (Home Access Express®) |

62 | 9.7 (2.3, 17.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 11.3 (3.4, 19.2) | 4.8 (−0.5, 10.2) | 21 (10.8, 31.1) | 11.3 (3.4, 19.2) | 40.3 (28.1, 52.5) | 1.6 (−1.5, 4.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Home: oral fluid rapid HIV self- test (OraQuick®) |

483 | 1.0 (0.1, 1.9) | 3.3 (1.7, 4.9) | 1.7 (0.5, 2.8) | 1.0 (0.1, 1.9) | 0.4 (−0.2, 1.0) | 33.7 (29.5, 38.0) | 56.3 (51.9, 60.7) | 2.5 (1.1, 3.9) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Don’t know | 64 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 3.1 (−1.1, 7.4) | 9.4 (2.2, 16.5) | 4.7 (−0.5, 9.9) | 1.6 (−1.5, 4.6) | 6.3 (0.3, 12.2) | 21.9 (11.7, 32) | 53.1 (40.9, 65.4) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | |

| Refuse to answer | 4 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 50.0 (1.0, 99.0) | 25.0 (−17.4, 67.4) | 25.0 (−17.4, 67.4) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable.

Discussion

This investigation provides insight into the HIV testing preferences among social media-using black, Hispanic, and white YMSM in the US, as well as implications for future efforts to increase HIV testing among this high HIV risk population. Despite the widespread availability of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in the US and its perceived advantages over other currently available HIV testing options, few social media-using YMSM had ever used this test or anticipated using it in the future. Although it was generally viewed positively by these YMSM, oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing was not preferred over other HIV testing options (particularly medical facility-based testing), was not a test that would be recommended to others frequently, and was not trusted as much as other tests when concerned about being HIV infected.

Previous researchers reported greater willingness by MSM to use the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test.22 For example, Xu, et al.31 conducted in-person interviews among 371 MSM in China and 73% indicated that they were willing to accept oral fluid testing. Greacen, et al.32 queried 5908 HIV-uninfected MSM in France through an internet-based survey who denied being aware of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing; of these MSM, 87% showed interest in using the test. Carballo-Diéguez, et al.33 conducted intensive in-person interviews of 57 MSM in New York City who reported infrequent condom use; of these 80% stated that it was likely they would use the test. We cannot know definitely why the social media-using black, Hispanic, and white YMSM in our investigation were less enthusiastic about the oral fluid rapid HIV self-test than MSM from other studies. We suspect that by asking participants to consider multiple domains about HIV testing preferences (e.g. what they are likely to use or would select for their next HIV test) and by forcing them to choose among realistic HIV testing alternatives that could be available to them, they made choices more in concert with their true preferences, as opposed to their interest. Inquiring about the oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in isolation might overestimate interest in, willingness to use, and actual future behaviors. Variations in populations studied, types of questions asked, and questionnaire format and delivery methods and other methodological differences also could account for disparities in our observations as compared with prior investigations.

However, if promoting oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing is envisioned as a means to encourage black, Hispanic, and white YMSM to be tested, it appears that a few aspects about this testing method might modestly prompt willingness to use it in the future. According to the opinions of these YMSM, privacy in getting tested and receiving test results, facilitating more frequent testing and getting tested sooner, a sense of empowerment over one’s sexual health, as well as believing it would motivate sexual partners also to be tested are positive aspects of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing that might change viewpoints affirmatively towards the test. Future efforts encouraging the use of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing could emphasize these perceived positive attributes associated with the test that could be incorporated into interventions that motivate its use or decrease reluctance to try it. It is encouraging that these positive opinions about the test appear uniform and unaffected by the demographic characteristics (including race/ethnicity), HIV testing history, and HIV risk-taking behaviors of this population.

On the other hand, multiple barriers to this HIV testing method revealed in this investigation could impede its adoption by black, Hispanic, and white YMSM in the US: concerns about understanding the test results, linking to care if tested HIV positive, accessing counseling services, and the accuracy of the test. Overcoming these barriers also must be addressed in any future interventions aimed at increasing oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing among this population. Paying for the test also is a barrier to the test’s utilization, as compared with other HIV testing options. If cost is a concern, the test appears to be favored less as an option. Although the results must be interpreted with caution, given the hypothetical nature of the scenarios presented in the questions, fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing might be more popular than oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing among these YMSM. If this finding is verified in future studies, perhaps this test might hold even more promise in facilitating HIV testing in this population.

One potential use of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing to increase HIV testing utilization among black, Hispanic, and white YMSM is to distribute the tests through an internet-based program.34 In 2014, Rosengren, et al.35 used the social media site Grindr™ to advertise free oral fluid rapid HIV self-tests in Los Angeles, CA, to adult black or Hispanic MSM. There were 333 test requests: 74% for tests to be mailed to the recipients, 17% for vouchers, and 8% for vending machine codes. Our study results suggest that given the HIV testing preferences expressed by the YMSM in our investigation, oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing might not be preferred over other HIV testing options in practice. Perhaps if these YMSM were encouraged to use existing HIV testing options through internet-based outreach initiatives, HIV testing utilization by this hard-to-reach population might be greater, and costs of implementing such a program could be less than if oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing was offered in isolation. We recommend that future research should investigate direct comparison of HIV testing options instead of oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing in isolation.

This investigation had several limitations. Despite our obtaining a large, diverse sample of black, Hispanic and white YMSM, we cannot claim that the observed results definitively represent the behaviors, preferences, or opinions of all YMSM in the US, whether they engage in social media use. We know of no way to verify that our or any other sample is representative of the underlying population. We do believe that given our efforts to use a variety of social media platforms and recruit participants across the US that our sampling options are reasonable. Of particular importance, self-reported data might not reflect actual testing behaviors, whether of the past or in the future. However, the data do provide insight into what these behaviors might be and how they could be influenced. Although we adjusted for demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and HIV sexual risk-taking behaviors in our regression models, unmeasured confounders (e.g. local HIV test option availability) might have affected the observed results.

In conclusion, social media-using black, Hispanic, and white US YMSM showed little prior experience with or future plans to use oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing, as compared with other HIV testing options, even though they generally had favorable opinions about the test. The results do suggest that their preferences for oral fluid rapid HIV self-testing might increase when considering selected aspects about the test. Future interventions could incorporate these aspects as a way to motivate YMSM to try the test. Barriers to the test, such as concerns about its accuracy and its costs, might continue to impede its adoption. Although yet not available, fingerstick rapid HIV self-testing might be another option to increase HIV testing by this high HIV risk population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R21 NR023869). ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier: NCT02369627.

Footnotes

Author statements

Ethical approval

Lifespan-Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review Board 1 approval, (Ref No: 014713).

Competing interests

None declared.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.12.002.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HIV testing among men who have sex with mend21 cities, United States, 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(21):694–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subpopulation estimates from the HIV incidence surveillance system—United States, 2006. MMWR – Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(36):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Schillinger JA, Shepard C, Sweeney M, Blank S. Men who have sex with men have a 140-fold higher risk for newly diagnosed HIV and syphilis compared with heterosexual men in New York city. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230e1ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torrone EA, Bertolli J, Li J, Sweeney P, Jeffries WL, Ham DC, et al. Increased HIV and primary and secondary syphilis diagnoses among young men e United States, 2004–2008. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(3):328–335. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822e1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses among men who have sex with men—33 states, 2001e2006. MMWR – Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(25):681–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vital signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behaviors among youths—United States. MMWR – Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(47):971–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with mend21 cities, United States, 2008. MMWR – Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(37):1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlayson TJ, Le B, Smith A, Bowles K, Cribbin M, Miles I, et al. HIV risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, 21 U.S. Cities, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(14):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolis AD, Joseph H, Belcher L, Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA. ‘Never testing for HIV’ among men who have sex with men recruited from a sexual networking website, United States. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oster AM, Johnson CH, Le BC, Balaji AB, Finlayson TJ, Lansky A, et al. Trends in HIV prevalence and HIV testing among young MSM: five United States cities, 1994–2011. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl. 3):S237–S247. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0566-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Anderson JE, Behel S, Secura GM, Bingham T, et al. Recent HIV testing among young men who have sex with men: correlates, contexts, and HIV seroconversion. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):183–192. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204507.21902.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A web-based survey of HIV testing and risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with mend—United States, 2012. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colfax GN, Lehman JS, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Vranizan K, Fleming PL, et al. What happened to home HIV test collection kits? Intent to use kits, actual use, and barriers to use among persons at risk for HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2002;14(5):675–682. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000005533a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM. Willingness to take a free home HIV test and associated factors among internet-using men who have sex with men. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10(6):357–364. doi: 10.1177/1545109711404946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNeil DG. Rapid HIV home test wins federal approval. N Y Times. 2012 Jul;3 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.OraSure Technologies Inc. OraQuick® In-home rapid HIV test package insert. Bethlehem, PA: OraSure Technologies Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.OraSure Technologies Inc. OraQuick® ADVANCE rapid HIV-1/2 antibody test package insert. Bethlehem, PA: OraSure Technologies, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.NAM Publications. aidsmap: HIV testing and transmission, rapid HIV tests, accuracy. London, UK: NAM Publications; [(accessed 30 November 2016)]. Available at: http://www.aidsmap.com/Accuracy/page/1323395/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prazuck T, Karon S, Gubavu C, Andre J, Legall JM, Bouvet E, et al. A finger-stick whole-blood HIV self-test as an HIV screening tool adapted to the general public. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0146755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Verster A, Baggaley R. Attitudes and acceptability on HIV self-testing among key populations: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(11):1949–1965. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pequegnat W, Rosser BR, Bowen AM, Bull SS, DiClemente RJ, Bockting WO, et al. Conducting internet-based HIV/STD prevention survey research: considerations in design and evaluation. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(4):505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenc T, Marrero-Guillamon I, Aggleton P, Cooper C, Llewellyn A, Lehmann A, et al. Promoting the uptake of HIV testing among men who have sex with men: systematic review of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(4):272–278. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.048280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenc T, Marrero-Guillamon I, Llewellyn A, Aggleton P, Cooper C, Lehmann A, et al. HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM): systematic review of qualitative evidence. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):834–846. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller S, Jones J, Erbelding E. Choice of rapid HIV testing and entrance into care in Baltimore City sexually transmitted infections clinics. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(4):237–243. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stein R, Green K, Bell K, Toledo CA, Uhl G, Moore A, et al. Provision of HIV counseling and testing services at five community-based organizations among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):743–750. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9821-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen MY, Bilardi JE, Lee D, Cummings R, Bush M, Fairley CK. Australian men who have sex with men prefer rapid oral HIV testing over conventional blood testing for HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(6):428–430. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.009552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohall A, Dini S, Nye A, Dye B, Neu N, Hyden C. HIV testing preferences among young men of color who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1961–1966. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis MA, Uhrig JD, Ayala G, Stryker J. Reaching men who have sex with men for HIV prevention messaging with new media: recommendations from an expert consultation. Ann Forum Collab HIV Res. 2011;13(3):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xun H, Kang D, Huang T, Qian Y, Li X, Wilson EC, et al. Factors associated with willingness to accept oral fluid HIV rapid testing among most-at-risk populations in China. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greacen T, Friboulet D, Blachier A, Fugon L, Hefez S, Lorente N, et al. Internet-using men who have sex with men would be interested in accessing authorised HIV self-tests available for purchase online. AIDS Care. 2013;25(1):49–54. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Balan I. Will gay and bisexually active men at high risk of infection use over-the-counter rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners? J Sex Res. 2012;49(4):379–387. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.647117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Estem KS, Catania J, Klausner JD. HIV self-testing: a review of current implementation and fidelity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(2):107–115. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosengren AL, Huang E, Daniels J, Young SD, Marlin RW, Klausner JD. Feasibility of using Grindr™ to distribute HIV self-test kits to men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Health. 2016 doi: 10.1071/SH15236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.