Abstract

BACKGROUND

The safety and efficacy of aerobic exercise in heart failure (HF) patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) has not been well evaluated.

PURPOSE

This study examined if outcomes with exercise training in HF vary according to AF status.

METHODS

HF-ACTION randomized 2331 ambulatory HF patients with ejection fraction ≤35% to exercise training or usual care. We examined clinical characteristics and outcomes (mortality/hospitalization) by baseline AF status (past history of AF or AF on baseline EKG vs. no AF) using adjusted Cox models and explored an interaction with exercise training. We assessed post-randomization AF events diagnosed via hospitalizations for AF and reports of serious arrhythmia caused by AF.

RESULTS

Of 2292 patients with baseline rhythm data, 382 (17%) had AF, 1602 (70%) had sinus rhythm, and 308 (13%) had “other” rhythm. Patients with AF were older and had lower peak VO2. Over a median follow-up of 2.6 years, AF was associated with a 24% per year higher rate of mortality/hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53; 95% CI 1.34–1.74; p <0.001) in unadjusted analysis; this did not remain significant after adjustment (HR 1.15; 95% CI 0.98–1.35; p =0.09). There was no significant difference in AF event rates by randomized treatment assignment in the overall population or by baseline AF status (all p >0.1). There was no interaction between AF and exercise training on measures of functional status or clinical outcomes (all p >0.1).

CONCLUSIONS

AF in patients with chronic HF was associated with older age, reduced exercise capacity at baseline, and a higher overall rate of clinical events, but not a differential response to exercise training for clinical outcomes or changes in exercise capacity.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier

Keywords: fitness, cardiopulmonary reserve, exercise training, arrhythmia

Introduction

The disorders of atrial fibrillation (AF) and chronic heart failure (HF) are closely intertwined with aging; both are expected to rise in prevalence, stemming from a continued burgeoning of shared risk factors including hypertension, aging, and obesity (1). More than half of patients with HF develop AF, and greater than one-third with AF develop incident HF (2). In combination, they portend higher mortality risk compared with either in isolation (2).

Physical activity and exercise training improve symptoms and can have anti-arrhythmic effects in individuals with paroxysmal AF and may be protective against the development of AF (3–6). In patients with chronic HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), as shown in the HF-ACTION (Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training) study, exercise training is associated with improved exercise capacity, improved quality of life, and reduced all-cause mortality and hospitalization (7,8). In the HF-ACTION primary analysis, AF was highly predictive of the primary end point of all-cause mortality or hospitalization, independent of treatment arm, and was used in the adjusted model for the primary analysis (7). However, to date limited data characterize the implications of exercise training in individuals with both HF and AF and their risk for future AF events.

The HF-ACTION trial is the largest trial to date investigating the effects of aerobic exercise training in stable outpatients with HFrEF (7). Using the HF-ACTION study cohort, we a) examine the relationship between baseline AF status and outcomes with exercise training, and b) describe future AF events, in patients with chronic HF.

Methods

Trial Overview

The trial design and results of HF-ACTION have been previously reported (7,9). This multi-center, randomized controlled trial compared the long-term safety and efficacy of exercise training plus evidence-based heart failure medical therapy versus medical therapy alone in patients with chronic HF (EF <35%) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II to IV symptoms. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria regarding the management of AF. Patients were excluded if they had sustained AF with rapid ventricular response on the baseline exercise test performed before enrollment.

Supervised training involved aerobic exercise (walking, treadmill, or cycle ergometer) 3 times weekly for 36 sessions, followed by transition to a home-based exercise program for an additional 2 years. The exercise goal was 90 minutes per week for the first 3 months, followed by 120 minutes per week thereafter. Follow-up occurred over a median of 2.6 years. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee at each institution and the coordinating center. All patients provided written informed consent.

AF Status and Outcomes

Patient characteristics, medical history, health status, and physiological parameters at rest and during exercise testing were collected on standardized forms at baseline and repeated at 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months. Health status was measured with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and Beck Depression Inventory II (10,11). All patients underwent graded cardiopulmonary exercise testing to evaluate safety and exercise capacity at baseline, including a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) for assessment of baseline rhythm, and this testing was repeated at 3 months, 12 months, and 24 months. Performed using a modified Naughton treadmill protocol or a leg ergometer, exercise continued until sign- or symptom-limited maximal exertion was reached. Peak oxygen uptake (VO2) was defined as the VO2 at peak exercise, either within the last 90 seconds of exercise or the first 30 seconds of recovery, whichever was higher. Exercise volume was calculated for the subpopulation randomized to exercise therapy. Using metabolic equivalent hour (MET-h) of exercise per week to represent the product of exercise intensity (where 1 MET is ~3.5 ml O2 · kg−1 · min−1), exercise volume was derived during months 1 to 3 for patients who did not experience a clinical event or were not censored in that time period (12).

For the present study, AF status was determined by presence on ECG at baseline cardiopulmonary stress test or an investigator-reported past medical history of AF. Patients with and without AF were compared. In the AF study groups, the composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality and all-cause hospitalization and secondary endpoints of all-cause mortality alone and cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalization were assessed with and without adjustment for variables found to be significantly associated with outcomes in prior HF-ACTION analyses (13,14). The occurrence of new or recurrent AF events after randomization was diagnosed through investigator reports of AF hospitalizations or serious adverse arrhythmia caused by AF.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were reported by AF status. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages and compared using Pearson Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were reported as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

We used unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards models to assess the association between exercise training and each clinical outcome stratified by baseline AF status. Adjusted general linear models were also used to assess the association between exercise training and exercise capacity and health status outcomes stratified by baseline AF status. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were used to assess the association between exercise training and future AF events in the full trial population as well as by baseline AF status. We explored the interaction between AF and treatment assignment for the primary and secondary outcomes using adjusted Cox models. In the AF patients, we performed exploratory analysis investigating the association of resting heart rate control and anticoagulation use on clinical and quality of life outcomes using Cox proportional hazards modeling for mortality/hospitalization and general linear modeling for exercise capacity and health status outcomes. All analyses were then repeated separating the AF group into those with past history of AF and those with AF on baseline ECG to evaluate bias between the 2 populations. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses.

Results

Of the 2,331 patients enrolled in the HF-ACTION study, 39 patients (2%) were missing baseline EKG or documentation of AF status. Excluding another 308 (13%) patients with “other” rhythm on EKG, this analysis included 1984 patients: 382 (17%) with AF by past medical history only (n = 244) or rhythm on CPX (n = 138) and 1602 (70%) with sinus rhythm. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Overall, patients with AF were more likely to be older, male, and white compared to those without baseline AF. At baseline, patients with AF were more likely to have NYHA class III-IV symptom limitations and lower LVEF. They had higher burden of comorbidities including more diabetes, history of myocardial infarction, and worse renal function. All patients reported greater than 90% use of beta-blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers at baseline, but patients with AF had lower doses of beta-blockers and higher doses of loop diuretics. Furthermore, compared to patients in sinus rhythm, patients with AF had significantly higher utilization of anti-arrhythmic medications and lower baseline exercise capacity as measured by peak VO2 and 6-minute walk test distance. Even after adjusting for baseline covariates known to predict outcome, peak VO2 and 6-minute walk test remained statistically different between AF and sinus rhythm patients (p <0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). However, patients randomized to exercise training in both groups exhibited similar exercise volume between month 1 and month 3. AF patients reported similar baseline quality of life and depression as measured by the KCCQ and Beck Depression Inventory II score.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by baseline AF group

| Characteristic | Overall n = 1984 | AF n = 382 | Sinus Rhythm n = 1602 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.5 (50.4, 67.3) | 63.1 (55.7, 72.8) | 57.4 (49.4, 65.9) | <.001 |

| Female | 598/1984 (30.1%) | 61/382 (16.0%) | 537/1602 (33.5%) | <.001 |

| Race | <.001 | |||

| Black | 669/1955 (34.2%) | 78/378 (20.6%) | 591/1577 (37.5%) | |

| White | 1184/1955 (60.6%) | 280/378 (74.1%) | 904/1577 (57.3%) | |

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 29.9 (26.0, 35.4) | 29.4 (25.8, 34.7) | 30.1 (26.0, 35.5) | 0.045 |

| Resting systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 112 (101, 126) | 110 (102, 120) | 112 (100, 128) | 0.009 |

| Resting heart rate (beats per minute) | 71 (63, 79) | 70 (63, 80) | 71 (63, 79) | 0.91 |

| NYHA class | <.001 | |||

| II | 1275/1984 (64.3%) | 203/382 (53.1%) | 1072/1602 (66.9%) | |

| III | 693/1984 (34.9%) | 168/382 (44.0%) | 525/1602 (32.8%) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 25 (20, 30) | 24 (19, 30) | 25 (21, 31) | 0.01 |

| History of Diabetes | 634/1984 (32.0%) | 129/382 (33.8%) | 505/1602 (31.5%) | 0.40 |

| History of Previous MI | 828/1984 (41.7%) | 191/382 (50.0%) | 637/1602 (39.8%) | <.001 |

| History of Hypertension | 1178/1973 (59.7%) | 222/380 (58.4%) | 956/1593 (60.0%) | 0.57 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 20 (15, 27) | 24 (17, 33) | 19 (14, 26) | <.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 1877/1984 (94.6%) | 348/382 (91.1%) | 1529/1602 (95.4%) | <.001 |

| Carvedilol dose equivalents (mg) | 40 (25, 50) | 25 (13, 50) | 50 (25, 50) | 0.02 |

| Loop diuretic | 1518/1984 (76.5%) | 310/382 (81.2%) | 1208/1602 (75.4%) | 0.02 |

| Furosemide dose equivalents (mg) | 40 (40, 80) | 80 (40, 120) | 40 (40, 80) | <.001 |

| ACE/ARB | 1887/1984 (95.1%) | 355/382 (92.9%) | 1532/1602 (95.6%) | 0.03 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 874/1984 (44.1%) | 167/382 (43.7%) | 707/1602 (44.1%) | 0.88 |

| Digoxin | 862/1984 (43.4%) | 206/382 (53.9%) | 656/1602 (40.9%) | <.001 |

| Anti-arrhythmic | 243/1984 (12.2%) | 116/382 (30.4%) | 127/1602 (7.9%) | <.001 |

| Amiodarone | 202/243 (83.1%) | 99/116 (85.3%) | 103/127 (81.1%) | 0.38 |

| AICD | 676/1984 (34.1%) | 169/382 (44.2%) | 507/1602 (31.6%) | <.001 |

| Baseline exercise capacity | ||||

| Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) | 14.6 (11.6, 17.8) | 13.4 (10.7, 16.3) | 15.0 (11.9, 18.1) | <.001 |

| Peak heart rate with exercise (beats per minute) | 121 (106, 136) | 115 (97, 133) | 122 (108, 137) | <.001 |

| CPX duration (min) | 9.7 (7.0, 12.1) | 8.4 (6.0, 11.0) | 10.0 (7.3, 12.5) | <.001 |

| 6MWT distance (m) | 373 (300, 439) | 356 (274, 436) | 378 (305, 440) | <.001 |

| Exercise volume* (MET-h per week) | 3.8 (1.9, 6.1) (N=825) | 3.6 (1.9, 5.9) (N=155) | 3.8 (1.9, 6.2) (N=670) | 0.77 |

| KCCQ overall summary score | 68 (51, 83) | 66 (51, 83) | 68 (51, 84) | 0.28 |

| Beck depression score | 8 (4, 15) | 8 (4, 14) | 8 (4, 15) | 0.68 |

Values are median (interquartile range) or number (%).

Exercise volume is defined as metabolic equivalent-hour (MET-h) of exercise per week, where 1 MET is ~ 3.5 ml O2·kg−1·min−1. Exercise volume is limited to patients randomized to exercise testing only and is averaged from month 1–3. CPX = cardiopulmonary exercise

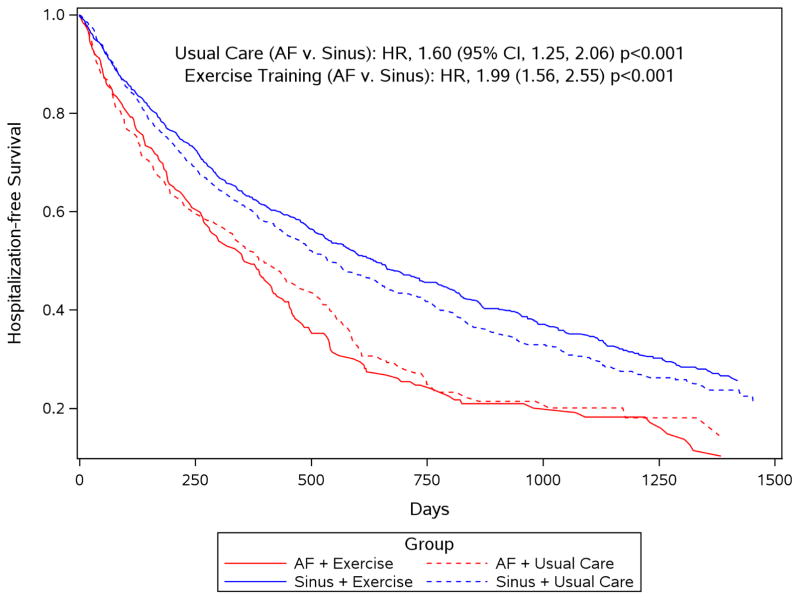

The relationship between all-cause death/hospitalization and AF groups is shown in Figure 1, and the clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2. Over a median follow-up of 2.6 years, in unadjusted analysis and regardless of randomized group, the primary outcome occurred in a significantly higher percentage of patients with AF (64.6%/year) than in patients in sinus rhythm (40.8%/year) (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.34–1.74; p <0.001). However, after adjustment for dosage of beta-blocker, KCCQ symptom stability, LVEF, country, sex, ventricular conduction, Weber class, blood urea nitrogen, and mitral regurgitation, AF status was not significantly associated with increased risk for mortality/hospitalization (HR, 1.15; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.35; p =0.09). Each of the other cardiovascular endpoints was also associated with worse outcomes in patients with AF in the univariate model, but differences were attenuated when adjusted for other clinical variables. Additionally, there was no evidence of a differential effect of exercise training based on AF status (all interaction p >0.1).

Figure 1. Hospitalization-free survival by atrial fibrillation group and exercise training group.

In univariate analysis, heart failure (HF) patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) (red lines) experienced significantly worse long-term hospitalization-free survival than HF patients in sinus rhythm (blue lines), regardless of their randomization group (usual care [AF vs. sinus]: HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.25 to 2.06; exercise training [AF vs. sinus]: HR 1.99, 95% CI 1.56 to 2.55).

Table 2.

Association Between Baseline AF Group and Outcomes by Treatment Assignment (Reference = Sinus).

| Outcome | Rate per 100 person years (number of events) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Adj. p for interaction assignment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Overall | AF | Sinus | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | ||

| All-cause mortality or all- cause hospitalization | ||||||||

| Full population | 44.5 (1305) | 64.6 (295) | 40.8 (1010) | 1.53 (1.34,1.74) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.98,1.35)* | 0.09 | |

| Exercise training | 42.6 (643) | 66.3 (153) | 38.3 (490) | 0.59 | ||||

| Usual care | 46.4 (662) | 62.9 (142) | 43.3 (520) | |||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||||||

| Full population | 6.2 (315) | 10.6 (97) | 5.2 (218) | 2.07 (1.63,2.63) | <0.001 | 1.24 (0.95,1.60)† | 0.11 | |

| Exercise training | 6.1 (157) | 10.9 (51) | 5.1 (106) | 0.97 | ||||

| Usual care | 6.3 (158) | 10.3 (46) | 5.4 (112) | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalization | ||||||||

| Full population | 13.3 (582) | 21.0 (156) | 11.8 (426) | 1.75 (1.46,2.11) | <0.001 | 1.25 (0.99,1.57)‡ | 0.06 | |

| Exercise training | 12.6 (279) | 20.9 (79) | 10.9 (200) | 0.53 | ||||

| Usual care | 14.1 (303) | 21.1 (77) | 12.6 (226) | |||||

Adjusted for dosage of beta-blocker, KCCQ symptom stability, ejection fraction (LVEF), country, sex, ventricular conduction, Weber class, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and mitral regurgitation.

Adjusted for sex, body mass index, loop diuretic dose, creatinine, exercise duration, ventricular conduction, Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina classification, and LVEF.

Adjusted for loop diuretic dose, LVEF, mitral regurgitation, ventricular conduction, KCCQ symptom stability, BUN, race, sex, age, Weber class, VE/VCO2.

We tested the interaction between AF status and randomization group for short-term functional and quality of life outcomes (Table 3). There were no significant interactions between baseline AF status and randomization group for change in quality of life and functional capacity from baseline to 3 months. Compared to patients in sinus rhythm at 3 months of follow-up, patients with AF in the exercise training group had similar improvements in distance in 6-minute walk test (median, 22 vs. 20 meters) and in peak VO2 (0.6 vs. 0.7 mL/min/kg). In patients with sinus rhythm, exercise training (as compared to usual care) was associated with a modest improvement in KCCQ overall summary score (5.6 vs. 2.6), consistent with the primary trial results in the overall population (8). Patient with AF reported small improvements in health status in both exercise and usual care groups (3.1 vs. 3.1). Indeed, a lower proportion of AF patients in exercise training experienced a clinically noticeable improvement of 5 or more points on KCCQ compared with patients in sinus rhythm assigned to exercise training (45.6% vs. 51.9%) (11).

Table 3.

Change in quality of life and short-term functional outcomes by exercise training group and atrial fibrillation (AF) group (baseline to 3 months).

| Outcome | Overall | AF | Sinus Rhythm | Adj. p for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in 6 minute walk distance* (m) | 0.22 | |||

| Exercise training | 20.1 (−15.2,59.7) | 21.6 (−9.8,57.0) | 20.0 (−15.2,60.7) | |

| Usual care | 4.8 (−28.7,37.8) | 0.0 (−43.6,25.9) | 5.7 (−27.0,42.0) | |

| Change in Peak VO2† (mL/kg/min) | 0.27 | |||

| Exercise training | 0.7 (−0.7,2.4) | 0.6 (−0.5,2.0) | 0.7 (−0.7,2.4) | |

| Usual care | 0.2 (−1.1,1.5) | 0.2 (−1.1,1.6) | 0.2 (−1.1,1.4) | |

| Change in KCCQ overall summary score‡ | 0.68 | |||

| Exercise training | 5.2 (−2.1,13.5) | 3.1 (−6.3,11.5) | 5.6 (−2.1,14.1) | |

| Usual care | 2.6 (−4.5,9.6) | 3.1 (−5.2,9.9) | 2.6 (−4.2,9.4) |

Adjusted for baseline 6-MWD, number of heart failure (HF) hospitalizations in the previous 6 months, resting heart rate, ejection fraction (LVEF), KCCQ clinical summary score, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER), smoking status, cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPX) duration, and peak VO2.

Adjusted for baseline peak VO2, age, sex, number of HF hospitalizations in the previous 6 months, ischemic etiology, insulin use, pacemaker, LVEF, BUN, body mass index (BMI), peak RER, race, and CPX duration.

Adjusted for baseline KCCQ overall summary score, age, peripheral vascular disease, biventricular pacemaker, Beck Depression score, BUN, BMI, Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina class, and peak VO2. Presented as Median (IQR)

Over median follow-up of 2.6 years, 5.5% (54/990) of patients randomized to exercise training, compared to 5.7% (57/994) of patients in usual care, experienced a post randomization AF event defined as a hospitalization due to AF or serious adverse event reported for symptomatic AF (p =0.8). Among those patients with AF, 10.9% (21/193) of those randomized to exercise training experienced subsequent AF events compared to 9% (17/189) in usual care (p = 0.5) (Online Table 4).

In sensitivity analyses separating the AF cohort into 2 groups (history of AF and documented AF on baseline ECG), we did not find significant differences in outcomes between the 2 (Online Tables 1–4). Despite the older age of subjects in the group with AF on ECG compared to patients in the AF history group (median 66 vs. 62 years), they exhibited similar cardiopulmonary reserve and performance parameters on their baseline CPX testing, with mean peak VO2 at 13.4 mL/kg/min for both groups. Both AF groups showed similarly high rates of all-cause mortality or hospitalization (64.2%/year and 65.4%/year for AF on ECG and AF by history) and no differential response to exercise training (Online Table 3). Since the rate of future AF event was generally low in the trial population, there was also no significant difference in future AF rates by randomization group between the two AF subgroups (Online Table 4).

In an exploratory analysis among patients with AF, we investigated the association of resting heart rate control on clinical outcomes. There was a trend toward a significant association between strict resting heart rate control of less than 80 beats per minute and all-cause death or hospitalization (p =0.05); however, this association was attenuated after multivariable adjustment (Table 4). There was also no significant association between strict heart rate control with improvement in functional status and quality of life outcomes (p >0.1; data not shown).

Table 4.

Association Between Resting Heart Rate Among AF Patients and Outcomes. Values are rate per 100 person years (number of events). Strict defined as <80 bpm.

| Outcome | Resting heart rate control | Unadj. p-value | Adj. p- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strict | Lenient | |||

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 60.5 (214) | 78.6 (81) | 0.054 | 0.14* |

| All-cause mortality | 11.1 (75) | 9.3 (22) | 0.47 | 0.36† |

| Cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalization | 21.2 (119) | 20.3 (37) | 0.76 | 0.35‡ |

Adjusted for dosage of beta-blocker, KCCQ symptom stability, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), region, sex, ventricular conduction, Weber class, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and mitral regurgitation.

Adjusted for sex, body mass index, loop diuretic dose, creatinine, exercise duration, ventricular conduction, and LVEF.

Adjusted for loop diuretic dose, LVEF, mitral regurgitation, ventricular conduction, KCCQ symptom stability, BUN, race, sex, age, Weber class, VE/VCO2.

Discussion

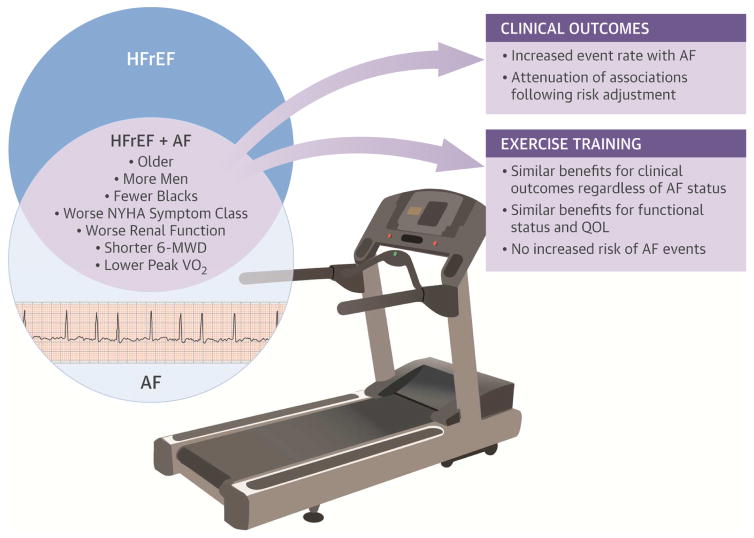

This analysis examined the relationship between AF and outcomes and exercise training and AF in patients with HFrEF. We had several important findings (Central Illustration). First, HF patients with AF were in general older and exhibited more comorbidities and lower exercise capacity at baseline. HF patients with AF had significantly worse outcomes across all clinical endpoints compared to those without AF; however, these relationships did not remain significant after adjustment for other important clinical variables. Second, there was no significant interaction between randomization group assignment and AF status on clinical or functional status outcomes. Despite having more severe HF, stable outpatients with HF and AF were able to receive similar benefits with exercise training when using a structured and monitored intervention. Importantly, exercise training did not lead to an increase in AF events in HF patients with AF.

Central Illustration. Exercise in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Benefits.

Benefits of exercise training has been shown in cohorts of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and in those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but rarely in patients with both conditions. We used data from the HF-ACTION trial to examine if outcomes with exercise training in HFrEF vary according to AF status. Despite having lower baseline exercise capacity and more comorbidities, HFrEF patients with AF were still able to achieve short-term functional benefits with exercise training. More research will be needed to study long term benefits of exercise training in this population. NYHA: New York Heart Association, 6-MWD: 6-minute walk distance, QOL: quality of life.

Prior studies have demonstrated worse prognosis when patients have AF and HF in combination. Two adjusted analyses of the Framingham Study population demonstrated up to 2-fold increased risk of death in patients with conjoint HFrEF and AF (2,15). In the SOLVD (Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction) Trials, AF in patients with reduced ventricular function was again independently associated with an increased risk of progressive heart failure and death (16). Similarly, AF was a strong predictor of mortality and hospitalization in the primary analysis of HF-ACTION (7). In our analysis, the increased mortality risk seen in HFrEF patients with AF was attenuated after adjustment for additional clinical variables, highlighting the convergence of common comorbidities. Nonetheless, a consistent trend in the adjusted effect estimates across the primary and secondary outcomes suggests persistent higher risk in patients with AF. Our study may have been underpowered to detect the independent risk of AF in HF due to a smaller cohort of AF patients.

Results from HF-ACTION showed that exercise training conferred modest improvements in exercise parameters (mean 4% increase in peak oxygen consumption) (7). In our analysis, patients with AF had significantly lower functional class and exercise capacity at baseline, as measured by peak VO2 (11% reduction compared to sinus rhythm) and 6-minute walk distance (6% reduction). These findings corroborate findings from historical studies that AF independently predict lower baseline exercise capacity (17). Despite having lower exercise capacity at baseline, patients with AF had similar modest improvements in peak VO2 (median 4% increase) and 6-minute walk distance (median 6% increase). Even modest improvements in peak VO2 may be important: as a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness, peak VO2 more strongly predicts future cardiovascular disease than measures of simple physical activity (18,19). Prior studies evaluating exercise training in AF patients have demonstrated larger improvements in exercise capacity (20,21). However, these studies were small in size and included few patients with heart failure.

In recent prospective observational cohort and trial populations, exercise training has been associated with positive benefits in patients with AF (3,4,22,23). In a recent 20,000 adult observational cohort study, investigators observed lower all-cause mortality in AF patients who self-reported regular physical activity (22). None of these studies evaluated patients with concomitant HF and AF. The HF-ACTION study showed that exercise training reduced all-cause mortality and hospitalizations and improved peak VO2 at 3 and 12 months in patients with chronic HF (7). This trial population afforded the unique opportunity to examine exercise training among patients with AF and HF within a clinical trial setting. In our analysis, exercise training had no differential effect based on AF status. While exercise training led to similar increases in functional capacity at 3 months in patients with AF as with those in sinus rhythm, we did not detect benefits in the primary or secondary clinical outcomes.

ACC/AHA HF Guidelines recommend exercise training in patients with chronic HF and reduced EF (24). Despite recognized benefits, however, theoretical concerns persist that exercise increases adrenergic tone and can provoke both ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias (25). A prior analysis from our group found no evidence for increased ICD shocks in HF patients who underwent exercise training (26). Recently, 2 groups independently showed that, regardless of rate or rhythm control strategy, exercise training in non-permanent AF patients was associated with reduced—not increased—short-term arrhythmia burden (3,4). In our analysis, exercise training was not associated with reduced future AF events. However, despite protocol designed attempts to simulate the number of medical contacts between study arms, it is likely that the exercise training arm experienced increased opportunity for AF identification given the additional supervised training sessions. Despite this setting of increased observation, those with underlying history of AF randomized to exercise were no more likely to experience a future AF event compared to usual care. Although we had limited power to detect anything other than a large treatment effect, our study parallels prior research in evaluating the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias in HF patients during exercise and reaffirms the overall safety of exercise training for this population (26).

Results from HF-ACTION also showed that exercise training conferred a modest but significant improvement in health status as measured by the KCCQ (8). In our analysis, patients with AF had significantly lower functional class and exercise capacity, but reported similar disease-specific health status compared to patients in sinus rhythm at baseline. And while patients with AF achieved similar short-term gains in cardiopulmonary reserve and functional status with exercise training, they reported minimal improvement in self-reported health status with exercise. Exercise has been previously shown to modestly improve quality of life and symptoms in patients with permanent AF, but with use of a different health status measure (Short Form-36) (21,27). The use of different instrument scales to assess health status and different types of exercise intervention makes it difficult, however, to compare these results to our study.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, HF-ACTION enrolled heart failure patients with power to detect a primary effect in mortality and hospitalization. As such, this secondary analysis evaluating a sub-population may be underpowered to detect an interaction effect. Second, incident AF that did not result in a hospitalization or reporting of severe adverse event was not captured in this analysis. At the same time, in the setting of a trial, ascertainment bias may be present that increased reporting of AF during more frequent medical surveillance. Even so, there was likely under detection and reporting of less symptomatic AF events, which may increase risk of type 2 error. Third, as HF-ACTION only enrolled patients with reduced EF, we can make no conclusions regarding exercise training in patients with AF and HF with preserved EF. Prior studies have described the association of AF with poor outcomes in HF with preserved EF, and further study will be needed to evaluate how exercise training affects this population (2,28). Fourth, adherence to HF-ACTION training protocol by enrolled subjects was below the targeted level and fell to 74 minutes out of a targeted 120 minutes. The results of this analysis need to be interpreted in the context of this modest adherence. Last, we did not adjust for multiplicity of statistical testing, and these results should be viewed as exploratory.

Conclusions

After adjustment for clinical variables, prevalent AF in ambulatory HF patients with reduced ejection fraction was associated with significantly reduced exercise tolerance and functional capacity, but not with mortality or hospitalization. This study supports current guideline recommendations that exercise can lead to short-term improvements in functional status in patients with both HF and AF. However, the long terms effects and best mode of exercise training in this medically complex population deserves further study.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

Competency in Patient Care

Although patients with heart failure (HF) who also have atrial fibrillation (AF) are typically older and have more comorbidities and limited exercise capacity compared to those without AF, they may still exhibit a positive functional response to exercise training.

Translational Outlook

Randomized trials are needed to compare the safety and efficacy of various exercise training protocols in patients with both HF and AF and develop criteria that identify patients most likely to improve.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: RJM receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (U10HL110312 and R01AG045551-01A1). The HF-ACTION trial was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial Fibrillation

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

- EF

Ejection Fraction

- HF

Heart Failure

- HFrEF

Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- VO2

Oxygen uptake

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest or relationships with industry.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and vice versa: temporal associations and differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. 2016;133:484–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME, et al. Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with atrial fibrillation: the CARDIO-FIT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:985–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malmo V, Nes BM, Amundsen BH, et al. Aerobic interval training reduces the burden of atrial fibrillation in the short term: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2016;133:466–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faselis C, Kokkinos P, Tsimploulis A, et al. Exercise capacity and atrial fibrillation risk in veterans: a cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:558–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapa S, Asirvatham SJ. A MET a day keeps arrhythmia at bay: the association between exercise or cardiorespiratory fitness and atrial fibrillation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1439–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn KE, Pina IL, Whellan DJ, et al. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM, Lee KL, et al. Heart failure and a controlled trial investigating outcomes of exercise training (HF-ACTION): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2007;153:201–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, et al. Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: a comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150:707–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keteyian SJ, Leifer ES, Houston-Miller N, et al. Relation between volume of exercise and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor CM, Mentz RJ, Whellan DJ. Covariate adjustment in heart failure randomized controlled clinical trials: a case analysis of the HF-ACTION trial. Heart Fail Clin. 2011;7:497–500. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Wojdyla D, et al. Factors related to morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure with systolic dysfunction: the HF-ACTION predictive risk score model. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:63–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dries DL, Exner DV, Gersh BJ, Domanski MJ, Waclawiw MA, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk for mortality and heart failure progression in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a retrospective analysis of the SOLVD trials. Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:695–703. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardaens K, Van Cleemput J, Vanhaecke J, Fagard RH. Atrial fibrillation is associated with a lower exercise capacity in male chronic heart failure patients. Heart. 1997;78:564–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.6.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeFina LF, Haskell WL, Willis BL, et al. Physical activity versus cardiorespiratory fitness: two (partly) distinct components of cardiovascular health? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers J, McAuley P, Lavie CJ, Despres JP, Arena R, Kokkinos P. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as major markers of cardiovascular risk: their independent and interwoven importance to health status. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osbak PS, Mourier M, Kjaer A, Henriksen JH, Kofoed KF, Jensen GB. A randomized study of the effects of exercise training on patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2011;162:1080–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegbom F, Stavem K, Sire S, Heldal M, Orning OM, Gjesdal K. Effects of short-term exercise training on symptoms and quality of life in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proietti M, Boriani G, Laroche C, et al. Self-reported physical activity and major adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the EURObservational Research Programme Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) General Registry. Europace. 2016 Jun 2; doi: 10.1093/europace/euw150. pii: euw150. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morseth B, Graff-Iversen S, Jacobsen BK, et al. Physical activity, resting heart rate, and atrial fibrillation: the Tromso Study. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2307–13. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2358–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piccini JP, Hellkamp AS, Whellan DJ, et al. Exercise training and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure: results from HF-ACTION (Heart Failure and A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise TraiNing) JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plisiene J, Blumberg A, Haager G, et al. Moderate physical exercise: a simplified approach for ventricular rate control in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008;97:820–6. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McManus DD, Hsu G, Sung SH, et al. Atrial fibrillation and outcomes in heart failure with preserved versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e005694. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.005694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.