HIV-1 infection of KCs leads to dysregulated innate immune response to LPS, and may play a role in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

Keywords: HIV-induced hepatic inflammation, liver fibrosis, microbial translocation

Abstract

End-stage liver disease is a common cause of non-AIDS-related mortality in HIV+ patients, despite effective anti-retroviral therapies (ARTs). HIV-1 infection causes gut CD4 depletion and is thought to contribute to increased gut permeability, bacterial translocation, and immune activation. Microbial products drain from the gut into the liver via the portal vein where Kupffer cells (KCs), the resident liver macrophage, clear translocated microbial products. As bacterial translocation is implicated in fibrogenesis in HIV patients through unclear mechanisms, we tested the hypothesis that HIV infection of KCs alters their response to LPS in a TLR4-dependent manner. We showed that HIV-1 productively infected KCs, enhanced cell-surface TLR4 and CD14 expression, and increased IL-6 and TNF-α expression, which was blocked by a small molecule TLR4 inhibitor. Our study demonstrated that HIV infection sensitizes KCs to the proinflammatory effects of LPS in a TLR4-dependent manner. These findings suggest that HIV-1-infected KCs and their dysregulated innate immune response to LPS may play a role in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis and represent a novel target for therapy.

Introduction

With effective ART, end-stage liver disease has emerged as a leading cause of non-AIDS-related mortality in HIV-infected patients [1]. As a result of shared routes of transmission, HCV and HBV are the most common liver diseases in HIV-infected patients, although other chronic liver diseases are emerging [2–5]. Given that HIV infection causes gut depletion of CD4+ T cells, it has been suggested that this results in increased microbial translocation and systemic immune activation [6]. Whereas microbial translocation has been implicated as a cofactor in fibrosis progression in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients [7], the mechanism(s) by which microbial translocation may promote hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in HIV-infected individuals have not been elucidated.

The liver is unique in that the majority of its blood flow is derived from the portal circulation. As blood enters the liver, it is distributed through the hepatic sinusoids, which are lined by a uniquely fenestrated endothelium interspersed with resident macrophages, also known as KCs. The HSCs reside between the endothelial cells and hepatocytes. Consequently, the low pressure flow combined with the fenestrations within the sinusoids create an environment that is primed for interactions among gut-derived pathogens, intrahepatic cell populations, and circulating cells of the immune system.

Liver fibrosis is characterized by a progressive replacement of the normal extracellular matrix with a high-density scar matrix composed of predominantly type I collagen. A central mediator of this fibrotic process is the HSC [8]. With liver injury and inflammation, this normally quiescent cell is transformed into a myofibroblastic cell that is fibrogenic, highly proliferative, and increasingly responsive to paracrine stimuli, such as from neighboring KCs [9].

HIV infection of KCs in viremic patients has been shown by both in situ hybridization for HIV-1 RNA [10, 11] and PCR for proviral DNA on FACS-purified KCs from livers of patients with AIDS [12]. KCs can also be productively infected with HIV in vitro [12]. Despite these in vivo and in vitro observations, no studies have examined the impact of HIV infection on KC function. Given that KCs are a known target of HIV, are responsible for the host response to translocated bacterial products, and are normally tolerant, and microbial translocation has been implicated in fibrosis progression in HIV patients, we hypothesized that HIV infection of KCs may alter their response to translocated microbial products.

Here, we show that HIV productively infects KCs, up-regulates cell-surface CD14 and TLR4 expression, and enhances their proinflammatory response to LPS in a TLR4-dependent manner. These findings suggest that HIV infection sensitizes KCs to translocated bacterial products, thereby promoting a dysregulated innate immune response that could promote hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human liver tissues

De-identified liver resection specimens from normal (colon cancer metastasis), HCV-infected, and HIV/HCV-coinfected patients were provided by S.R., S.F., M.S., and M.I.F. KCs were isolated, as detailed below, when adequate tissue was available. In all cases, HIV was effectively suppressed with ART. All HCV patients had detectable HCV RNA levels. Tissues were formalin fixed, frozen, or placed in RNA later for additional experiments. These studies have been approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board (GCO #06-0523 and #10-1211).

Isolation of human KCs from liver

KCs were isolated from surgical resection specimens (normal and HCV and HBV infected) by performing collagenase perfusion and mincing of liver. Cells were washed with PBS 4 times and pelleted at 50 G for 4 min. Cells were then resuspended in DMEM + 10% FBS, followed by differential centrifugation using Percoll 25% and 50% (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), as described [13]. Indicated cell layers were collected and plated (2 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate). KCs were enriched using rapid adherence and extensive washing with cold PBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C and maintained in DMEM media containing 10% FBS. After 2 wk in culture, flow cytometry revealed 80–95% KCs. RT-qPCR on RNA extracted from KCs was performed to determine the presence of significant contamination with T cells (primers to CD3) or endothelial cells (primers to CD31). cDNA from primary CD4+ T cells and human hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells (Cat. #5000; ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used as positive controls for CD3 and CD31 expression, respectively.

Immunofluorescence staining of CD68+ cells

Fresh, frozen human liver tissue sections from HCV-monoinfected, HIV/HCV-coinfected, and uninfected patients were fixed with 1:1 acetone:methanol and stained with antibodies against CD68 (green; ab955; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and collagen IV (magenta; Cat. #ab6586; Abcam) and nuclear counterstained with DAPI (blue). Stained sections were visualized by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy on a laser-scanning confocal TCS SP5 DM (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Images were taken of 10 high-power fields at 20× or 40× objective, and the number of KCs/mm2 quantified blindly.

Flow cytometry analyses

Flow cytometry was used to determine TLR4, CD68, CD14, CXCR4, and CCR5 expression in noninfected and HIVBaL-infected KCs. Cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.5% BSA at a concentration of 0.5–1 × 106 cells/ml. After addition of the FcR-blocking reagent, cells were incubated with anti-human TLR4 antibodies TLR4-PE (Cat. #312806; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-human CD14-PerCP 5.5 (Cat. #367110), anti-human CXCR4-alkaline phosphatase-Cy7 (Cat. #306528), and anti-human CCR5-PE (Cat. #313707) for 30 min. Cells were fixed and permeabilized at 4°C for 20 min, followed by intracellular staining with FITC-labeled anti-human CD68 (Cat. #333806; BioLegend), or for 30 min. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on an LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

HIV-1BaL replication in KCs

KCs were plated at concentration 2 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate. To determine replication of HIV-1BaL in KCs, R5 virus HIV-1BaL, purchased from Advanced Biotechnologies (Eldersburg, MD, USA), was used to infect cells at a MOI of 0.1. The virus was washed off at 3 h, followed by the addition of fresh medium. Media were serially collected, and HIV-1 p24 antigen production was measured by ELISA using the Science Applications International Corporation-Frederick kit (National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Frederick, MD, USA). To suppress HIV replication, KCs were treated with AZT (100 μM) and ritonavir (20 μg/ml) from U.S. National Institutes of Health AIDS Reagent Program, and p24 performed to assess impact.

Impact of HIV-1BaL infection on KC response to LPS

72 h post-HIV-1BaL-infection KCs were challenged with TLR4 ligand ultrapure LPS (TLR-pb5LPS; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) at a dose of 100 ng/ml for 4 h, followed by RNA extraction and RT-qPCR. Supernatants were collected for an ELISA assay at 24 h post-LPS treatment.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted by using RNeasy spin columns (Cat. #74136; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After treatment with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen), RT was performed on RNA by using the Clontech RNA to cDNA EcoDry kit (Takara Bio USA, Mountain View, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-qPCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Reactions were carried out in 10 μl by using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Cat. #1708884; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). All reactions were performed in triplicate. The concentration of primer pairs was 300 nM. All primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 1. All reactions were performed in triplicate. To make comparisons between samples and controls, the CT (defined as the cycle number at which the fluorescence is above the fixed threshold) values were normalized to the CT of ribosomal protein cDNA or β-actin in each sample.

ELISA assay

TNF-α and IL-6 production from KCs, infected and noninfected with HIV and treated with LPS, was measured by using the human TNF-α ELISA kit (Cat. #88-7346-86; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and human IL-6 ELISA kit (Cat. #88-7066-88; Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Blocking TLR4 signaling by using a small molecule

KCs, isolated as described above, were plated in 24-well plates, infected or noninfected with HIV, and treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and/or TAK-242 (3 μM; InvivoGen). TAK-242, also known as CLI-095, a small molecule, has been shown to inhibit TLR4 signaling selectively to suppress LPS-induced inflammation [14]. Twenty-four hours after LPS treatment, ±TLR4 inhibitor, supernatants were collected for IL-6 or TNF-α ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Data from repeated experiments were averaged and expressed as means ± sd. Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS using the Student's t-test, Welch's t-test, or one-way ANOVA analysis of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

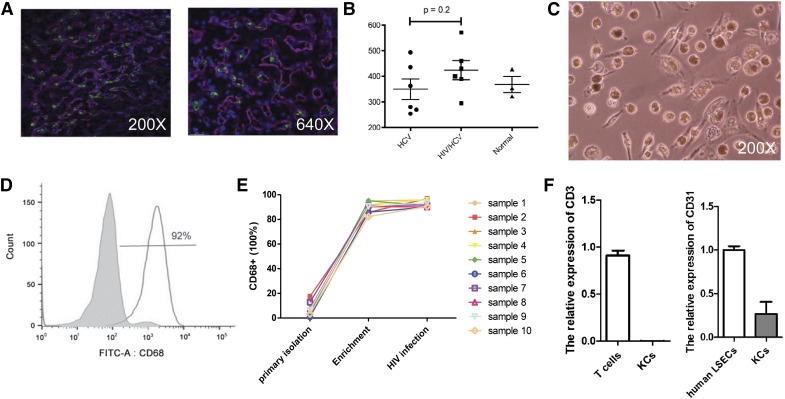

Isolation and characterization of liver-derived primary human KCs

Immunofluorescence CD68 staining (green) reveals KCs within the hepatic sinusoids (Fig. 1A). The median density of CD68+ cells was higher in HIV/HCV-coinfected than in normal or HCV-monoinfected patients; however, the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1B). Quantification of CD68 cells with immunostaining in ART-treated, HIV/HCV-coinfected patients revealed a range of 250–580 CD68+ cells/mm2 (Fig. 1B), which is similar to the range reported by others [15]. KCs were isolated and plated on plastic from normal livers, as described previously [13]. Phase-contrast photomicrographs confirmed KC morphology (Fig. 1C). After isolation, human KCs were enriched by rapid adherence and cultured for 2 wk. A high purity of KCs, was obtained and confirmed by intracellular CD68 FACS staining (Fig. 1D). Expression of CD68 with enrichment and HIV infection in 10 different patient samples demonstrates that with adherence enrichment, a high percentage of CD68+ cells is obtained, whereas HIV infection does not significantly increase CD68 expression (Fig. 1E). To confirm lack of significant contamination from T cells or endothelial cells in KC preparations, the relative expression of CD3 and CD31 was examined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1F). KCs express CXCR4 and CCR5, the 2 HIV coreceptors, as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Characterization of KCs isolated from HIV/HCV, HCV-infected, and normal livers.

(A) Immunofluorescence CD68 staining (green) reveals KCs within the hepatic sinusoids (left, 200× original magnification; right, 640× original magnification). (B) Number of KCs/mm2 quantitated and shown graphically. HCV and HIV/HCV, n = 6; normal, n = 3. (C) KC morphology (phase-contrast photomicrograph original magnification, 200×). (D) Representative FACS analyses of CD68 expression directly after KC isolation (gray histogram) and adherence enrichment of KCs (white histogram). (E) FACS demonstrating quantitative expression of CD68 in primary liver-derived KCs directly after isolation, with adherence enrichment, and after HIV infection (n = 10). (F) RT-qPCR confirms low expression of CD3 and CD31 in KC preparations compared with human T cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), respectively (n = 3 T cells and LSECs; n = 5 KCs).

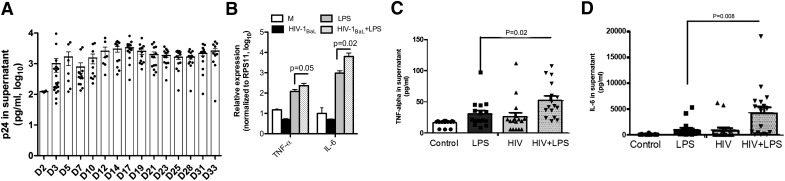

HIV-1BaL causes a noncytopathic, productive infection in primary human KCs

KCs, isolated from normal human liver, were infected with HIV-1BaL (MOI = 0.1), 2 wk after isolation. Virus was washed out extensively after 3 h of viral incubation and supernatant collected every 3–4 d for p24 ELISA (Fig. 2A). There was a significant increase in HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant from d 2 (210 ± 13 pg/ml) to d 14 (2105 ± 396 pg/ml), suggesting robust HIV replication in KCs. Importantly, HIV-1 infection of KCs did not induce major cytopathic effects, as suggested by p24 antigen expression at d 33 (1365 ± 298 pg/ml) in the supernatant of cultured KCs.

Figure 2. R5 tropic HIV-1 results in noncytopathic, productive infection of primary human KCs and enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS.

(A) KCs infected with HIV-1BaL at an MOI of 0.1 for 2 h, unbound virus was washed out extensively, and culture media were replaced. ELISA assay for HIV p24 antigen levels was done on culture media up to 33 days after infection [day 2 (D2)-day 33 (D33)]. HIV-infected and noninfected KCs were then challenged with LPS (100 ng/ml) and levels of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) examined, with and without LPS by RT-qPCR and ELISA. (B) Increased mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in HIV-infected KCs challenged with LPS was observed and correlated with cytokine expression level of (C) TNF-α and (D) IL-6 in culture supernatant analyzed by ELISA (8 different donors in duplicate). Data represent means ± sd. Student’s t test used to compare means. P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. RPS11, ribosomal protein S11; M, medium.

HIV-1BaL infection of primary human KCs enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS and increases cell-surface TLR4 expression

Given reports on increased immune activation in HIV patients and the association between microbial translocation and liver inflammation, we examined whether HIV infection of KCs increases their sensitivity to LPS. Seventy-two hours after infection with HIV-1BaL, RNA was extracted from mock and HIV-1-infected KCs, before and after LPS challenge (100 ng/ml for 2 h), and RT-qPCR was performed to quantify mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 2B). Supernatants were collected 24 h post-HIV infection for TNF-α and IL-6 ELISA.

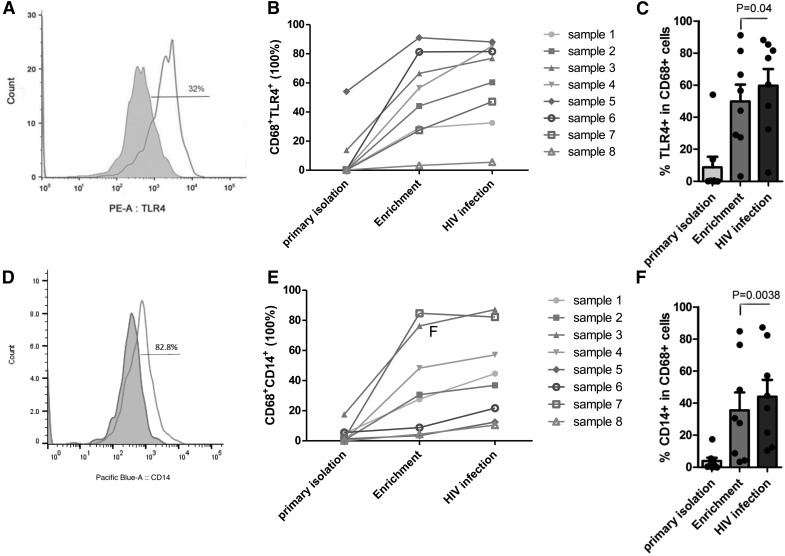

HIV-1BaL infection alone resulted in a decrease in the mRNA level of TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 2B), whereas treatment with LPS up-regulated the mRNA expression level of TNF-α and IL-6. HIV infection and LPS treatment significantly increased TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA expression compared with noninfected and LPS-treated KCs (Fig. 2B). Likewise, LPS alone increased TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine release, measured by ELISA (Fig. 2C and D). Importantly, infection with HIV-1 significantly increased cytokine production compared with noninfected KCs in response to LPS, suggesting a sensitization effect. HIV-infected KCs secrete more TNF-α (from 30.6 ± 5.7 to 52.17 ± 7.6 pg/ml) significantly more (from 919.55 ± 381 to 4487.19 ± 921 pg/ml) and IL-6 in response to LPS compared with noninfected KCs (Fig. 2C and D). There are reports indicating that TLR4 and CD14 membrane-associated receptors in macrophages recognize and signal in response to LPS stimulation, and this pathway is altered in HIV+ patients [16–18]. It has also been shown that HIV infection of human macrophages increases TLR4 expression, a known LPS receptor [19]. Therefore, we asked whether HIV infection of KCs alters expression of these receptors. The expression levels of CD14 and TLR4, in combination with CD68 (KC and macrophage marker), were evaluated in KCs before and after HIV infection (Fig. 3A–F). As shown in Fig. 3A–C, enrichment increases TLR4 expression, but expression is increased further by HIV infection. Likewise, CD14 expression was increased in response to HIV infection (Fig. 3D–F).

Figure 3. HIV infection increases cell-surface expression of TLR4 and CD14 in KCs.

(A) Representative FACS analyses of TLR4 expression before (gray histogram) and after (white histogram) HIV infection and LPS treatment. (B) FACS demonstrating quantitative expression level of TLR4 and CD68 in KCs derived from 8 patients directly after isolation and with adherence enrichment and HIV infection KCs. (C) Cumulative data on the TLR4 expression level in CD68-positive cells after HIV infection (n = 8; P = 0.04). (D) Representative FACS analyses of CD14 expression before (gray histogram) and after (white histogram) HIV infection and LPS treatment. (E) FACS demonstrating quantitative expression level of CD14 and CD68 in KCs derived from 8 patients directly after isolation and with adherence enrichment and HIV infection. (F) Cumulative data on the CD14 expression level in CD68-positive cells after HIV infection (n = 8; P = 0.0038).

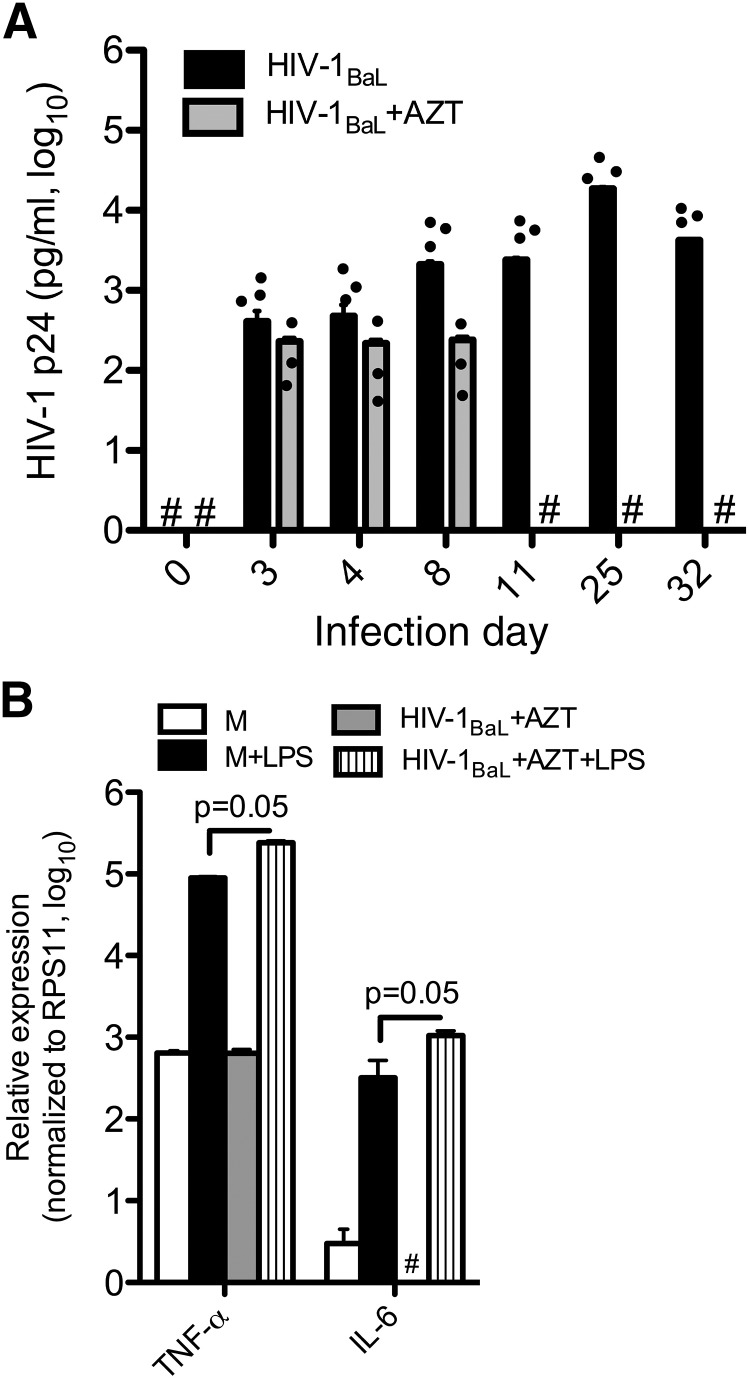

In vitro suppression of HIV-1BaL replication of KCs by AZT and protease inhibitors does not abrogate the dysregulated proinflammatory response to LPS

With currently available ART plasma, HIV-1 RNA in patients is very low. To study whether in vitro suppression of HIV-1BaL replication in KCs could restore their response to TLR4 ligand, we infected primary KCs with HIV-1BaL and treated with AZT (100 μM) and ritonavir (20 μg/ml). HIV-1BaL replication was completely suppressed in KCs treated with AZT and ritonavir (undetectable) compared with cells without drugs (2400 ± 0.2 pg/ml) by d 11 postinfection (Fig. 4A). Next, we asked whether response to LPS was restored in KCs with undetectable HIV-1 p24 antigen expression. KCs infected with HIV-1BaL or mock infected in the presence or absence of AZT and ritonavir were treated with LPS, as described above. RNA was extracted, and RT-qPCR was performed. Although HIV-1BaL-infected KCs treated with AZT have an undetectable HIV-p24 antigen expression level, they maintained an exaggerated response to LPS compared with noninfected cells (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, AZT suppressed mRNA expression of IL-6 after HIV infection, but this effect was overcome by LPS treatment, suggesting that HIV-1BaL infection alters KC response to TLR4 ligands and makes them more sensitive to LPS, despite adequate suppression of viral replication.

Figure 4. In vitro HIV-1-infected KCs with undetectable HIV p24 antigen levels produce increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS.

KCs infected with HIV-1BaL and treated with AZT (100 μM) and ritonavir (20 μg/ml; labeled AZT). (A) p24 antigen expression level in supernatant of KCs, as measured by ELISA, reveals complete suppression of HIV replication by day 11. (B) d 11 KCs treated with LPS reveals increased mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-6 in response to LPS, as assessed by RT-qPCR. Experiments were performed from at least 3 different donors. #Undetectable levels.

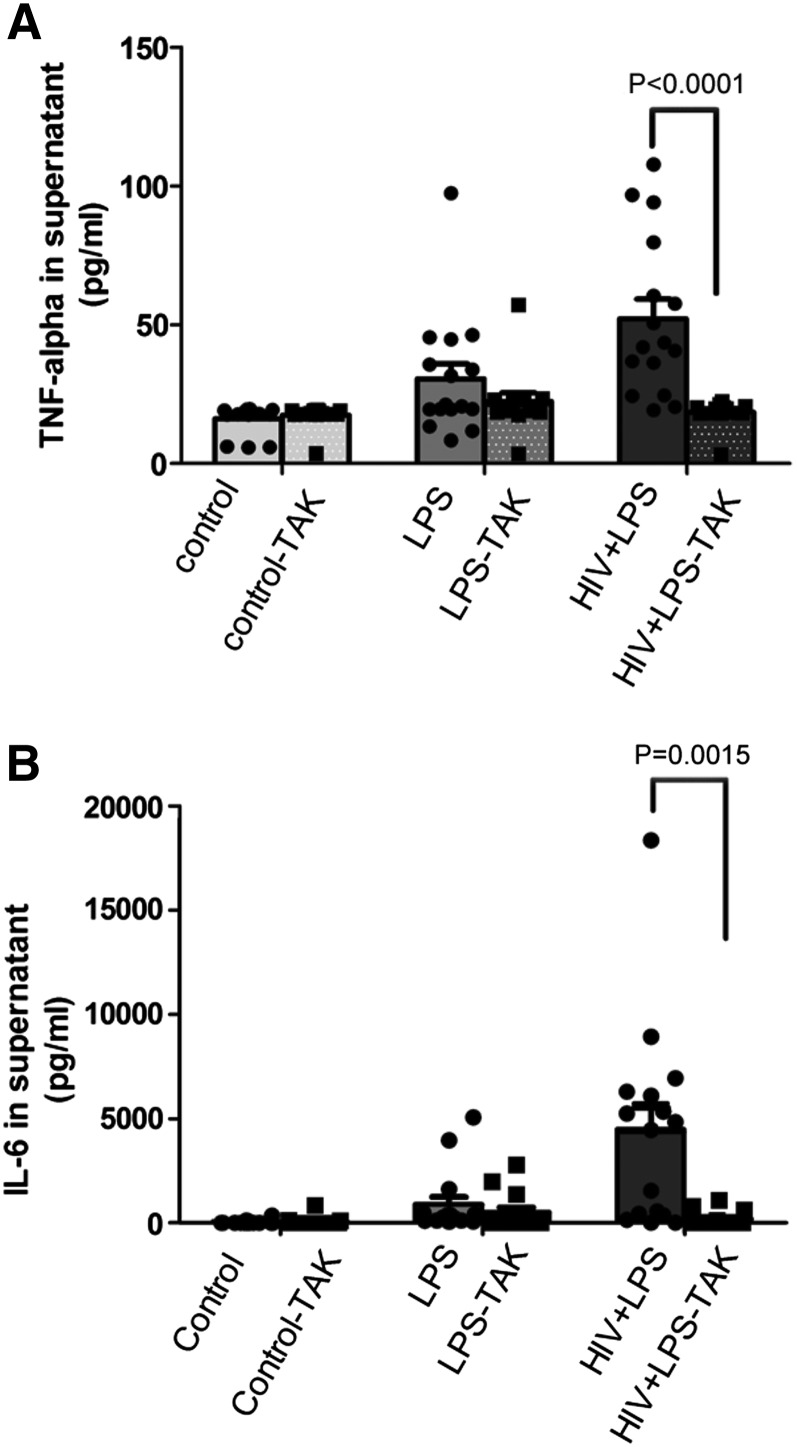

Blocking the TLR4 signaling pathway abrogated the dysregulated proinflammatory response to LPS in HIV-infected KCs

As we showed high production of TNF-α and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated, HIV-infected KCs, indicating that HIV-infected KCs are hypersensitive to LPS stimulation, and we showed up-regulation of cell-surface TLR4 and CD14 receptor expression, we asked whether these effects were mediated by TLR4. CD14 and TLR4 have been shown to play a critical role in host response to LPS stimulation [16, 20]. To further address the mechanism of the dysregulated proinflammatory response of HIV-1BaL-infected KCs to LPS, we used a TLR4 inhibitor (small molecule) to block TLR4 signaling by LPS. TLR4 blocking significantly reduced the TNF-α response to LPS in HIV-infected and LPS-treated KCs (from 52.2 ± 7.6 to 18.5 ± 2.6 pg/ml) and had much less effect on noninfected KCs (from 30.6 ± 5.7 to 22.5 ± 3.9 pg/ml) treated with LPS (Fig. 5A). Likewise, a slight decline of IL-6 production was induced by the TLR4 inhibitor in LPS-treated KCs (from 1192.4 ± 380.8 to 515.9 ± 200.8 pg/ml), but the production of IL-6 in LPS-stimulated, HIV-infected KCs was dramatically down-regulated by the TLR4 inhibitor (from 3982.4 ± 920.9 to 199.3 ± 86.7 pg/ml; Fig. 5B), suggesting a critical role of TLR4 in the inflammatory response of KCs. Consistently, these results suggest that the augmented response to LPS stimulation in HIV-infected KCs may be a result of increased TLR4 expression and subsequent downstream signaling.

Figure 5. HIV increases TNF-α and IL-6 in a TLR4-dependent manner.

KCs were either treated with LPS or infected by HIV, followed by LPS challenge ± the TLR4 inhibitor (TAK). ELISA for TNF-α (A) and IL-6 (B) demonstrates an increase in TNF-α and IL-6 with HIV infection and a significant reduction in the presence of a TLR4 inhibitor (8 different donors in duplicate). Individual data points are superimposed on bar graphs. Data represent means ± sd.

DISCUSSION

HIV-infected patients with chronic liver disease can have rapid liver fibrosis progression, but the mechanisms are not completely understood. Whereas effects on the adaptive immune system clearly play a role, the impact of HIV infection on the innate immune response and implications for hepatic inflammation and fibrosis have not been elucidated. It is known that HIV infects resident hepatic macrophages (KCs), both in vitro and in vivo, and KCs are responsible for binding and clearing translocated bacterial products [10–12]. In addition, HIV infection may be associated with increased microbial translocation, as a result of increased gut permeability, which occurs early after HIV infection and is not completely restored with ART [6, 21]. Increased microbial translocation has been implicated in promoting fibrosis progression [7]. Given their location in the sinusoidal space, KCs are the first line of defense against microbial translocation, and they develop tolerance to steady-state levels of bacterial products under physiologic conditions. Therefore, KCs play a critical role in the liver’s ability to deal with translocated bacterial products.

Whereas there is no ideal marker for human KCs, CD68 (an intracellular protein) is most commonly used. It has been reported that HIV/HCV-coinfected livers have fewer CD68+ cells than those of HCV-monoinfected patients, and KC numbers increase in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients who have been treated effectively with ART [15]. The authors postulate that HIV may be cytopathic for KCs, and subsequent lower KC numbers in coinfected patients may result in a reduction in phagocytosis of translocated bacterial products and thus, increased hepatic inflammation and systemic immune activation [15]. In addition, whereas many have shown HIV infection of KCs in vivo and in vitro, no studies have examined the impact of HIV infection on KC biology. In our small sample size, we did not detect significant differences in the numbers of CD68 cells in HIV-infected or noninfected livers, but our study was not powered for this comparison. Therefore, whether HIV is cytopathic to KCs in vivo is not clear. However, in vitro HIV infection of KCs did not result in cell killing and resulted in robust production and release of p24 into the cell culture supernatant, up to 1 mo.

First, it is known that patients with HIV/HCV coinfection have greater necroinflammation on liver biopsy than HCV-monoinfected patients, and increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion from KCs may be important in promoting this process [22]. Reduction in hepatic necroinflammatory activity correlates with the duration of ART and effective HIV suppression [23], further supporting the notion that HIV infection of KCs could promote hepatic inflammation. Furthermore, HIV+ patients are more susceptible to a number of liver diseases, such as alcohol-related liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, both of which may be associated with increased microbial translocation [24, 25]. Moreover, despite effective ART, HIV/HCV-coinfected patients have higher rates of decompensation and higher wait list mortality than HCV-monoinfected patients, suggesting that factors other than direct effects on the adaptive immune response may be impacted by HIV infection [22]. Viral suppression and CD4 reconstitution alone are not sufficient to reduce mortality rates of end-stage liver disease to those of HCV-monoinfected patients [26]. The understanding of mechanisms for this effect will be important in managing this aging cohort of patients. The contribution of HIV-infected KCs and their dysregulated response to LPS to this observation deserve further exploration.

In this study, we specifically looked into the response of HIV-infected KCs to LPS as the prototypic and classic TLR4 ligand. In monocyte-derived macrophages, HIV infection up-regulates TLR2 and TLR4 expression [19], and increased expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in HIV/HCV-coinfected cirrhotic livers has been reported [27]. Therefore, our finding that HIV up-regulated TLR4 and CD14 cell-surface expression suggests this as a possible mechanism for the dysregulated response of KCs to LPS. We further investigated whether blocking of TLR4 signaling in HIV-infected KCs with the small molecule TAK-242 known inhibitor of the TLR4 pathway will abolish this dysregulated response to LPS [14, 28]. We showed that blocking of the TLR4 signaling pathway abrogated the dysregulated proinflammatory response of HIV-infected KCs.

In addition, studies on TLR4 single nucleotide polymorphisms in humans, particularly T399I and D299G, are reported to be associated with a blunted response to LPS, and this has been shown to be predictive of protection from the progression of liver fibrosis [29, 30]. Our results extend the role of TLR4 in the context of HIV infection and microbial translocation by confirming that hyper-responsiveness of HIV-infected KCs to LPS could lead to an increased proinflammatory profile and consequently, enhanced hepatic inflammation and fibrosis.

Further studies will need to examine whether the effects of HIV are specific to TLR4 ligands or whether the effect is more global (TLR2, TLR3). In addition, the effect of endogenous TLR4 ligands, such as damage-associated molecular patterns, on HIV-infected KCs will be studied [31]. Lastly, our results are in agreement with published data that whereas ART suppresses HIV replication, it does not fully turn off the immune activation from bacterial translocation [6]. In support of this concept, we observed an anti-inflammatory effect of AZT, but this effect was overcome in HIV-infected cells exposed to LPS. It also has been shown that small alveolar macrophages from viremic, HIV-1-infected individuals harbor HIV-1 at high frequencies relative to CD4+ T cells, and HIV infection of alveolar macrophages impacts their phagocytic ability [32]. Whether HIV infection of KCs has a similar effect will be examined, given this cell's critical role in clearing translocated products, and may contribute to the higher systemic levels of LPS and chronic immune activation observed in HIV patients.

Finally, as tissue-based macrophages are potential reservoirs for HIV-1, and the liver is a very immunotolerant organ, where a number of hepatotropic viruses live for decades, the environment may be conducive to viral persistence of HIV-1 within KCs. Therefore, future studies will examine whether KCs may be a reservoir for HIV-1.

In conclusion, we report for the first time that HIV-1 infection of the resident hepatic macrophages, KCs, results in up-regulation of CD14 and TLR4 expression and a dysregulated response to LPS with increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Moreover, despite effective ART, these cells maintain a dysregulated immune response to LPS. The blocking of the TLR4 signaling pathway abrogated the dysregulated proinflammatory response of HIV-infected KCs, suggesting the importance of this pathway in modulating this response. Our findings suggest that HIV-1-infected KCs and their dysregulated innate immune response to LPS may play a role in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis and represent a novel target for therapy.

AUTHORSHIP

M.B. conceived of and designed the experiments. A.M., L.Z., F.H., F.C., R.B., A.P., and Y.S. performed the experiments. A.M., L.Z., M.B.B., A.R., M.I.F., S.F., S.R., M.S., A.B., and M.S. analyzed the data. A.M., L.Z., and M.B.B. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was fully funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant Numbers R56DK92128 and R01DK108364 (to M.B.B.).

Glossary

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- CT

cycle threshold

- Cy7

cyanine 7

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIVBaL

human immunodeficiency virus BaL R5-tropic laboratory-adapted strain

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- KC

Kupffer cell

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- TAK-242

Resatorvid (TLR4 inhibitor)

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 1077

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weber R., Sabin C. A., Friis-Møller N., Reiss P., El-Sadr W. M., Kirk O., Dabis F., Law M. G., Pradier C., De Wit S., Akerlund B., Calvo G., Monforte Ad., Rickenbach M., Ledergerber B., Phillips A. N., Lundgren J. D. (2006) Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1632–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter M. J. (2006) Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J. Hepatol. 44 (1 Suppl) S6–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman K. E., Rouster S. D., Chung R. T., Rajicic N. (2002) Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34, 831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vallet-Pichard A., Mallet V., Pol S. (2012) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and HIV infection. Semin. Liver Dis. 32, 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stabinski L., Reynolds S. J., Ocama P., Laeyendecker O., Ndyanabo A., Kiggundu V., Boaz I., Gray R. H., Wawer M., Thio C., Thomas D. L., Quinn T. C., Kirk G. D.; Rakai Health Sciences Program (2011) High prevalence of liver fibrosis associated with HIV infection: a study in rural Rakai, Uganda. Antivir. Ther. (Lond.) 16, 405–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenchley J. M., Price D. A., Schacker T. W., Asher T. E., Silvestri G., Rao S., Kazzaz Z., Bornstein E., Lambotte O., Altmann D., Blazar B. R., Rodriguez B., Teixeira-Johnson L., Landay A., Martin J. N., Hecht F. M., Picker L. J., Lederman M. M., Deeks S. G., Douek D. C. (2006) Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 12, 1365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balagopal A., Philp F. H., Astemborski J., Block T. M., Mehta A., Long R., Kirk G. D., Mehta S. H., Cox A. L., Thomas D. L., Ray S. C. (2008) Human immunodeficiency virus-related microbial translocation and progression of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 135, 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansal M., Friedman S. (2004) Fibrogenesis. In Encyclopedia of Gastroenterology (Gores G., Johnson L., eds.), Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman S. L. (2001) The hepatic stellate cell. In Seminars in Liver Disease (Berk P. D., ed.), Vol. 21 Thieme, New York, 307–452. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y. Z., Dieterich D., Thomas P. A., Huang Y. X., Mirabile M., Ho D. D. (1992) Identification and quantitation of HIV-1 in the liver of patients with AIDS. AIDS 6, 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Housset C., Lamas E., Courgnaud V., Boucher O., Girard P. M., Marche C., Brechot C. (1993) Presence of HIV-1 in human parenchymal and non-parenchymal liver cells in vivo. J. Hepatol. 19, 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hufert F. T., Schmitz J., Schreiber M., Schmitz H., Rácz P., von Laer D. D. (1993) Human Kupffer cells infected with HIV-1 in vivo. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6, 772–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alabraba E. B., Curbishley S. M., Lai W. K., Wigmore S. J., Adams D. H., Afford S. C. (2007) A new approach to isolation and culture of human Kupffer cells. J. Immunol. Methods 326, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamoto T., Ii M., Kitazaki T., Iizawa Y., Kimura H. (2008) TAK-242 selectively suppresses Toll-like receptor 4-signaling mediated by the intracellular domain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 584, 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balagopal A., Ray S. C., De Oca R. M., Sutcliffe C. G., Vivekanandan P., Higgins Y., Mehta S. H., Moore R. D., Sulkowski M. S., Thomas D. L., Torbenson M. S. (2009) Kupffer cells are depleted with HIV immunodeficiency and partially recovered with antiretroviral immune reconstitution. AIDS 23, 2397–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perera P. Y., Mayadas T. N., Takeuchi O., Akira S., Zaks-Zilberman M., Goyert S. M., Vogel S. N. (2001) CD11b/CD18 acts in concert with CD14 and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 to elicit full lipopolysaccharide and taxol-inducible gene expression. J. Immunol. 166, 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trøseid M., Lind A., Nowak P., Barqasho B., Heger B., Lygren I., Pedersen K. K., Kanda T., Funaoka H., Damås J. K., Kvale D. (2013) Circulating levels of HMGB1 are correlated strongly with MD2 in HIV-infection: possible implication for TLR4-signalling and chronic immune activation. Innate Immun. 19, 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tachado S. D., Li X., Bole M., Swan K., Anandaiah A., Patel N. R., Koziel H. (2010) MyD88-dependent TLR4 signaling is selectively impaired in alveolar macrophages from asymptomatic HIV+ persons. Blood 115, 3606–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández J. C., Stevenson M., Latz E., Urcuqui-Inchima S. (2012) HIV type 1 infection up-regulates TLR2 and TLR4 expression and function in vivo and in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 28, 1313–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Togbe D., Schnyder-Candrian S., Schnyder B., Doz E., Noulin N., Janot L., Secher T., Gasse P., Lima C., Coelho F. R., Vasseur V., Erard F., Ryffel B., Couillin I., Moser R. (2007) Toll-like receptor and tumour necrosis factor dependent endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 88, 387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piconi S., Trabattoni D., Gori A., Parisotto S., Magni C., Meraviglia P., Bandera A., Capetti A., Rizzardini G., Clerici M. (2010) Immune activation, apoptosis, and Treg activity are associated with persistently reduced CD4+ T-cell counts during antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 24, 1991–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page E. E., Nelson M., Kelleher P. (2011) HIV and hepatitis C coinfection: pathogenesis and microbial translocation. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 6, 472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta S. H., Thomas D. L., Torbenson M., Brinkley S., Mirel L., Chaisson R. E., Moore R. D., Sulkowski M. S. (2005) The effect of antiretroviral therapy on liver disease among adults with HIV and hepatitis C coinfection. Hepatology 41, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi D., O’Grady J., Dieterich D., Gazzard B., Agarwal K. (2011) Increasing burden of liver disease in patients with HIV infection. Lancet 377, 1198–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingiliz P., Benhamou Y. (2009) Elevated liver enzymes in HIV monoinfected patients on HIV therapy: what are the implications? J. HIV Ther. 14, 3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullen C. K., Laird G. M., Durand C. M., Siliciano J. D., Siliciano R. F. (2014) New ex vivo approaches distinguish effective and ineffective single agents for reversing HIV-1 latency in vivo. Nat. Med. 20, 425–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merchante N., Rivero-Juárez A., Téllez F., Merino D., Ríos-Villegas M. J., Ojeda-Burgos G., Omar M., Macías J., Rivero A., Pérez-Pérez M., Raffo M., López-Montesinos I., Márquez-Solero M., Gómez-Vidal M. A., Pineda J. A.; Grupo Andaluz para el Estudio de las Hepatitis Víricas (HEPAVIR) de la Sociedad Andaluza de Enfermedades Infecciosas (SAEI). (2016) Liver stiffness predicts variceal bleeding in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with compensated cirrhosis. AIDS doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001358 [Epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsunaga N., Tsuchimori N., Matsumoto T., Ii M. (2011) TAK-242 (resatorvid), a small-molecule inhibitor of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 signaling, binds selectively to TLR4 and interferes with interactions between TLR4 and its adaptor molecules. Mol. Pharmacol. 79, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arbour N. C., Lorenz E., Schutte B. C., Zabner J., Kline J. N., Jones M., Frees K., Watt J. L., Schwartz D. A. (2000) TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat. Genet. 25, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Chang M., Abar O., Garcia V., Rowland C., Catanese J., Ross D., Broder S., Shiffman M., Cheung R., Wright T., Friedman S. L., Sninsky J. (2009) Multiple variants in Toll-like receptor 4 gene modulate risk of liver fibrosis in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis C infection. J. Hepatol. 51, 750–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L., Seki E. (2012) Toll-like receptors in liver fibrosis: cellular crosstalk and mechanisms. Front. Physiol. 3, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jambo K. C., Banda D. H., Kankwatira A. M., Sukumar N., Allain T. J., Heyderman R. S., Russell D. G., Mwandumba H. C. (2014) Small alveolar macrophages are infected preferentially by HIV and exhibit impaired phagocytic function. Mucosal Immunol. 7, 1116–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]