Abstract

Trust is essential to the development of healthy, secure, and satisfying relationships (Simpson, 2007a). Attachment styles provide a theoretical framework for understanding how individuals respond to partner behaviors that either confirm or violate trust (Hazan & Shaver, 1994). The current research aimed to identify how trust and attachment anxiety might interact to predict different types of jealousy and physical and psychological abuse. We expected that when experiencing lower levels of trust, anxiously attached individuals would report higher levels of both cognitive and behavioral jealousy as well as partner abuse perpetration. Participants in committed romantic relationships (N = 261) completed measures of trust, attachment anxiety and avoidance, jealousy, and physical and psychological partner abuse in a cross-sectional study. Moderation results largely supported the hypotheses: Attachment anxiety moderated the association between trust and jealousy, such that anxious individuals experienced much higher levels of cognitive and behavioral jealousy when reporting lower levels of trust. Moreover, attachment anxiety moderated the association between trust and nonphysical violence. These results suggest that upon experiencing distrust in one’s partner, anxiously attached individuals are more likely to become jealous, snoop through a partner’s belongings, and become psychologically abusive. The present research illustrates that particularly for anxiously attached individuals, distrust has cascading effects on relationship cognitions and behavior, and this should be a key area of discussion during therapy.

Keywords: attachment anxiety, romantic jealousy, intimate partner violence, emotional abuse, physical abuse

Trust is critical in developing secure, intimate, and satisfying relationships (Simpson, 2007a). Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Rholes & Simpson, 2004) provides a useful framework for understanding associations between trust and jealousy in romantic relationships. Individual differences in attachment styles influence the way in which trust develops over time (Givertz, Woszidlo, Segrin, & Knutson, 2013; Hazan & Shaver, 1994). The current research aimed to identify how trust is associated with different types of jealousy and perpetration of physical and psychological abuse as well as whether these associations are moderated by attachment anxiety.

TRUST IN ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS

One of the first conceptualizations of trust delineated three components: the appraisal of partners as reliable and predictable, the belief that partners are concerned with one’s needs and can be depended on in times of need, and feelings of confidence in the strength of the relationship (Rempel, Holmes, & Zanna, 1985). In fact, trust that one’s partner has their best interests at heart is one of the most important and highly valued qualities in romantic relationships (Clark & Lemay, 2010; Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Reis, Clark, & Holmes, 2004), predicting many positive individual and relational outcomes (Arriaga, Reed, Goodfriend, & Agnew, 2006; Lemay, Clark, & Feeney, 2007; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000; see Simpson, 2007a, 2007b for reviews). Conversely, reporting lower levels of trust in romantic relationships is associated with negative relationship outcomes. For example, Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, and Rubin (2010) found that less trusting individuals reported greater negative reactivity to daily relational conflict. Moreover, when both partners were lower in trust, there was greater variability in relationship evaluations. The authors suggest that as a consequence, individuals with lower levels of trust tend to monitor and occasionally test their partner’s degree of support and responsiveness. This may occur because distrust has the potential to be accompanied by a belief or concern that one’s partner may leave the relationship for a better alternative. Thus, when a relationship lacks trust, it allows for the potential development of detrimental cognitive patterns such as negative attributions, suspicion, and jealousy.

ATTACHMENT ANXIETY

Attachment orientations evince a fundamental concern with relationship dependence and security; much of the foundation of attachment theory is based on whether individuals feel comfortable trusting others and whether partners can serve as a secure base. Attachment security develops when caregivers are perceived as available and responsible and occurs when individuals have positive working models of themselves and others (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). For example, securely attached individuals tend to believe that they are worthy of love and that close others can be trusted and counted on. Therefore, they are comfortable with closeness and do not worry excessively about abandonment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Conversely, attachment anxiety is characterized by a negative view of one’s self and a positive view of others (i.e., preoccupied attachment; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Anxiously attached individuals tend to worry that close others cannot be relied on and experience intense and chronic fear of rejection (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003). They actively monitor the romantic partner’s behavior for indications of availability (or unavailability) and often perceive otherwise ambiguous cues as threatening to the relationship (Collins, 1996). Furthermore, anxious individuals tend to ruminate over these perceived threats (Shaver & Hazan, 1993) and catastrophize about the relationship’s future (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005). The current research was designed to test differences in individual and relational outcomes (i.e., jealousy and partner abuse perpetration) when anxious individuals experience partner distrust.

ROMANTIC JEALOUSY

Romantic jealousy is considered a complex combination of thoughts (i.e., cognitive jealousy), emotions (i.e., emotional jealousy), and behaviors (i.e., behavioral jealousy) that result from a perceived threat to one’s romantic relationship. This perceived loss or threat comes from the perception of a potential romantic attraction between one’s partner and a rival (G. White & Mullen, 1989). Researchers have identified two fundamentally different aspects of jealousy: the experience and the expression. Specifically, the jealousy experience refers to an individual’s cognitive and emotional reactions in connection with being jealous. Cognitive jealousy represents a person’s rational or irrational thoughts, worries, and suspicions concerning a partner’s infidelity (e.g., I believe my partner may be seeing someone else), whereas emotional jealousy refers to a person’s feelings of upset in response to a jealousy-evoking situation (e.g., I would be very upset if my partner became involved with someone else). Alternatively, jealousy expression refers to the different behavioral reactions, manifestations, or coping methods one uses to deal with feeling jealous (Buunk & Dijkstra, 2001, 2006; Guerrero, Andersen, Jorgensen, Spitzberg, & Eloy, 1995; Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989). Behavioral jealousy involves detective/protective measures a person takes when relationship rivals (real or imagined) are perceived to be a threat (e.g., going through the partner’s belongings, looking through the partner’s text messages or e-mails). Previous research has shown that these three facets of jealousy (i.e., cognitive, emotional, behavioral) are differentially associated with relationship outcomes. Specifically, cognitive jealousy and behavioral jealousy have been found to be negatively associated with relationship satisfaction and commitment (Andersen, Eloy, Guerrero, & Spitzberg, 1995; Aylor & Dainton, 2001; Bevan, 2008). Alternatively, emotional jealousy was either associated with positive feelings (e.g., love; Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989) or not related to relationship satisfaction and commitment (Bevan, 2008; Sidelinger & Booth-Butterfield, 2007). Thus, cognitive and behavioral jealousy were of central interest to the current research; emotional jealousy was included, but specific hypotheses were not made regarding emotional jealousy.

More recently, researchers have examined different jealousy-evoking partner behaviors (Dijkstra, Barelds, & Groothof, 2010) as well as jealousy-evoking rival characteristics (Dijkstra & Buunk, 2002). Interestingly, Dijkstra et al. (2010) found that the second most jealousy-evoking partner behavior, next to actual reports of infidelity, was electronic communication. Specifically, individuals reported feeling jealous in response to actions such as their partners e-mailing and text messaging members of the opposite sex as well as their partners sharing a strong emotional connection with opposite sex individuals they communicate with online. With the emergence of electronic communication as a significant jealousy-evoking behavior, behavioral jealousy also now includes behaviors aimed at monitoring this type of communication (Marshall, Bejanyan, Di Castro, & Lee, 2013).

Research examining individual factors associated with jealousy suggests trust is an important factor. A recent study found that lower levels of trust were associated with increased Facebook jealousy (Marshall et al., 2013). Other research examining individual’s motives for engaging in “snooping” behavior (e.g., reading partner’s e-mail without permission, searching through partner’s belongings) also found trust to be an important factor. Specifically, individuals who perceived that their partners disclosed less personally relevant information to them were more likely to engage in snooping behavior, especially when they reported lower levels of trust (Vinkers, Finkenauer, & Hawk, 2011). Together, these findings indicate that distrust is an important determinant in experiencing and expressing jealousy. This study aims to further refine this association through examining trust and jealousy in the context of attachment theory.

The association between anxious attachment and jealousy has been well established. Anxious individuals tend to experience higher levels of jealousy (Buunk, 1997), suspicion and worry that their partner will leave them for someone else (i.e., cognitive jealousy; Guerrero, 1998), and respond to jealousy-inducing situations with elevated levels of fear, sadness, and anger (Sharpsteen & Kirkpatrick, 1997). Individuals higher in attachment anxiety also report increased monitoring of their partner’s behavior for signs of extradyadic relationships and increased surveillance behavior (i.e., behavioral jealousy), which includes closely watching the partner’s daily activities, spying, or going through the partner’s belongings to look for signs of infidelity (Guerrero, 1998; Guerrero & Afifi, 1998; Guerrero et al., 1995).

Research also suggests that trust differs as a function of attachment styles. Secure attachment styles are positively associated with trust in romantic relationships, whereas anxiously attached individuals have lower levels of trust (e.g., Brennan & Shaver, 1995; Collins & Read, 1990; Feeney & Noller, 1990; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994; Mikulincer, 1998b; Mikulincer & Erev, 1991; Simpson, 1990). Moreover, insecure individuals showed heightened accessibility of negative trust-related memories, reported fewer positive trust episodes over time, and dealt with trust violations in relationally maladaptive ways (Mikulincer, 1998b). Thus, the appraisal and processing of trust-related experiences and accompanying responses are related to individuals’ working models of relationships and might underlie attachment-style differences in trust.

The current research tests the possibility that anxious individuals may report higher levels of jealous thoughts and cognitions as well as engage in more snooping behavior when experiencing lower trust in their partner. A second objective of this research was to examine potential behavioral consequences of trust and attachment anxiety. Research has noted strong associations between jealousy and relationship conflict, aggression, and violence (Buss, 2000; Hansen, 1991; Harris, 2003; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, McCullars, & Misra, 2012; Stets & Pirog-Good, 1987). We wished to evaluate whether anxiously attached individuals might also report higher levels of partner abuse perpetration when experiencing low levels of trust in their relationships.

INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN YOUNG ADULTS

Intimate partner violence (IPV) occurs at alarming rates among adolescents and college-age young adults, with approximately one in three dating couples experiencing violence within their relationships (Straus, 2008; J. White & Koss, 1991), and many experience repeated victimization (Bonomi, Anderson, Rivara, & Thompson, 2007; Breiding, Black, & Ryan, 2008). Research has suggested that IPV is particularly common among young adults and college-age individuals because some studies have found that IPV rates are highest between the ages of 15 and 25 years (Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2012; Halpern, Spriggs, Martin, & Kupper, 2009; O’Leary, 1999; Straus, 2004). Furthermore, a recent study spanning 15 years found that reports of IPV victimization increased and decreased nonlinearly between the ages of 17 and 30 years (van Dulmen et al., 2012), indicating that IPV is most prevalent in adolescent and college-age relationships.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has distinct categories concerning relationship violence, dividing violent acts into physical violence, sexual violence, and psychological or emotional violence (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 2002). Thus, two separate categories can be considered: physical and nonphysical violence. Some research estimates that up to 35% of adolescents and young adults experience physical violence within their relationships (Arias, Samios, & O’Leary, 1987; Henton, Cate, Koval, Lloyd, & Christopher, 1983; Luthra & Gidycz, 2006; Muñoz-Rivas, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007; O’Keefe, Brockopp, & Chew, 1986; Straus, 2008, 2011); rates of nonphysical abuse (e.g., emotional, social, or verbal abuse) may be higher because this age group may tend to de-emphasize and not report such types of aggression as violence. For example, Miller (1995) found that many women reported experiences of nonphysical forms of abuse but did not recognize these events as abuse; rather, they seemed to think that such behaviors were normative in the context of relationships.

Overall, research has found that individuals who are anxiously attached are more likely to engage in IPV perpetration, an association that has been supported with marital and clinical samples (Holtzworth-Munroe, Meehan, Herron, Rehman, & Stuart, 2003; Waltz, Babcock, Jacobson, & Gottman, 2000) as well as college student samples (Bookwala & Zdaniuk, 1998; Davis, Ace, & Andra, 2000; Orcutt, Garcia, & Pickett, 2005; Wheeler, 2002). Longitudinal research has found that experiences of little warmth, trust, and communication from parents, all indicators of insecure attachment, were associated with subsequent IPV for men (Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998). Other research has found that anxiously attached individuals may react with more anger when perceiving a potential relationship threat (Mikulincer, 1998a). It is hypothesized that anxiously attached individuals fear abandonment by their romantic partners; they do not feel that their partner is predictable and dependable (i.e., lack of trust) and therefore react with expressions of anger (Follingstad, Bradley, Helff, & Laughlin, 2002; Mayseless, 1991; Roberts & Noller, 1998). Currently, findings are unclear regarding the pattern of association between attachment insecurity (i.e., anxious vs. avoidant) and type of IPV (physical vs. psychological; Gormley & Lopez, 2010).

In general, the literature on trust, attachment anxiety, jealousy, and partner abuse reveals that these phenomena are complex and that there are both individual and relational factors at play. When experiencing lower levels of trust, individuals behave in ways that emphasize protection from hurt and rejection rather than in ways that promote interdependence, which can result in further distancing from the partner (Murray, Derrick, Leder, & Holmes, 2008; Murray, Holmes, & Collins, 2006; Murray, Holmes, Griffin, Bellavia, & Rose, 2001; Murray et al., 2011). The risk regulation model (Murray et al., 2006; Murray et al., 2011) suggests that individuals who trust their partner have the emotional capital to prioritize the relationship above the self, whereas those with lower levels of trust tend to place priority on self-goals. Thus, it is possible for individuals who do not trust their partners to be more likely to engage in maladaptive relationship behaviors and aggression (e.g., name-calling or insulting during conflict, damaging the partner’s belongings).

Given findings from the literature on trust, attachment anxiety, and jealousy, we hypothesized that distrust in one’s partner would be associated with higher levels of both cognitive and behavioral jealousy (Hypothesis 1) and that this association would be particularly strong for individuals who are higher in anxious attachment (Hypothesis 2). We also expected that distrust would be associated with higher levels of physical and psychological partner perpetration (Hypothesis 3), particularly among anxiously attached individuals (Hypothesis 4).

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Individuals in committed romantic relationships of at least 3 months were recruited from a large metropolitan university. Two hundred sixty-one individuals (85% female) participated in the study. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 52 years (M = 22.51, SD = 4.79), and were ethnically diverse (36.78% White, 18.39% Black/African American, 17.62% Asian, 7.28% Multiethnic, and 19.16% other). Relationship length ranged from 1 month to 27.20 years (M = 3.02 years, SD = 3.33 years, Md = 2.16 years). Regarding relationship status, 6.13% of the sample reported casually dating, 51.87% reported exclusively dating, 21.84% indicated they were nearly engaged, 6.13% were engaged, and 13.03% were married.

Participants were recruited through flyers posted around the psychology building and via an online research management system. Interested individuals were instructed to sign up for the study via the online research management system. After signing up, participants were provided the link to the online survey, which they completed at their leisure. Upon entering the survey, all participants reviewed the informed consent document, provided consent, and were routed to the survey. Participants received extra course credit as an incentive for participation.

Measures

Trust

Trust was measured using the Trust Scale (Rempel & Holmes, 1986). This 17-item measure is designed to gauge levels of trust in one’s relationship partner. Each item is answered based on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include, “My partner has proven to be trustworthy, and I am willing to let him or her engage in activities, which other partners find too threatening” and “Even when I don’t know how my partner will react, I feel comfortable telling him or her anything about myself, even those things of which I am ashamed.” An overall trust score was calculated by taking a mean of all the items (α = .88).

Jealousy

Romantic jealousy was measured using the Multidimensional Jealousy Scale (Pfeiffer & Wong, 1989). Participants reported how cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally jealous they are. Each subscale contains eight items. The Cognitive Jealousy subscale asks participants how often they have a particular set of thoughts. An example item is, “I suspect that [my partner] is secretly seeing someone of the opposite sex.” Each item was rated on a 7-point scale (1 = never, 7 = always; α = .93). The Emotional Jealousy subscale asks participants how they would emotionally react to a set of situations. The situations described include items such as, “[My partner] works very closely with a member of the opposite sex [in school or the office].” Each item was rated on a 7-point scale (1 = very pleased; 7 = very upset; α = .91). Finally, the Behavioral Jealousy subscale asks participants how often they engage in a set of behaviors. These behaviors include actions such as, “I look through [my partner]’s drawers, handbag, or pockets.” Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = never, 7 = always; α = .87).

Attachment Anxiety

Attachment anxiety and avoidance were measured using the short form of the Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (Wei, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007). This 12-item measure has two subscales, each containing six items. The Attachment Anxiety subscale includes items such as, “I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner” (α = .72). The second subscale, the Attachment Avoidance scale includes items such as, “I want to get close to my partner, but I keep pulling back” (α = .66). Each item was rated on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration

Physical perpetration was measured using the Perpetration subscale of the short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2S; Straus & Douglas, 2004). This 10-item subscale assesses perpetration of violence in the participant’s current relationship. Participants rated the frequency of specific aggressive acts on an 8-point scale ranging from 0 (this has never happened) to 7 (more than 20 times in the past year). Example items include the following: “My partner insulted or swore or shouted or yelled at me,” “My partner destroyed something belonging to me or threatened to hit me,” and “My partner punched or kicked or beat me up” (α =.86). The CTS2S includes two positively worded items for perpetration (i.e., “I explained my side or suggested a compromise for a disagreement with my partner” and “I showed respect for or showed that I cared about my partner’s feeling about an issue we disagreed on”). These items were excluded for the purpose of these analyses because the lack of these behaviors does not indicate the presence of relationship violence.

Nonphysical Abuse

Nonphysical abuse was measured using the Non-Physical Abuse of Partner Scale (Garner & Hudson, 1992). This 25-item scale assesses non-physical abuse perpetrated within the participant’s current relationship. Sample items include, “I make fun of my partner’s ability to do things” and “I scream and yell at my partner” (α = .94). Participants rated the frequency of perpetrating nonphysical aggressive acts on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (all of the time).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 1. Overall, participants reported higher levels of emotional jealousy (M = 3.93, SD = .82) than cognitive (M = 1.68, SD = .84) or behavioral (M = 1.68, SD = .69) jealousy. Trust was significantly negatively associated with cognitive and behavioral jealousy, anxious attachment, and both physical and psychological abuse (all p < .001). Moreover, Cognitive Jealousy and Behavioral Jealousy subscales were positively associated with attachment anxiety and with both types of abuse. Approximately 75% of the sample reported perpetrating some IPV during their lifetime; the most prevalent forms reported were insulting, swearing, or yelling at their partner (70%), followed by pushing, shoving, or slapping their partner (27%); destroying something belonging to their partner or threatening to hit them (19%); and insisting on sex when their partner did not want to without using force (16%). All other forms of IPV (i.e., using a weapon, punching, kicking, or beating up a partner) occurred in less than 14% of the sample.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust | — | ||||||

| 2. Behavioral jealousy | −.30*** | — | |||||

| 3. Emotional jealousy | .02 | .22*** | — | ||||

| 4. Cognitive jealousy | −.46*** | .55*** | .23*** | — | |||

| 5. Anxious attachment | −.32*** | .44*** | .18** | .40*** | — | ||

| 6. IPV perpetration | −.23*** | .42*** | .08 | .31*** | .27*** | — | |

| 7. Nonphysical abuse | −.28*** | .48*** | .13* | .34*** | .35*** | .48*** | — |

|

| |||||||

| M | 5.23 | 1.68 | 3.93 | 1.68 | 3.54 | 0.52 | 1.69 |

| SD | 1.04 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 1.12 | 0.61 | 0.67 |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Moderation Analyses

We hypothesized that individuals would experience higher levels of jealousy and higher levels of perpetration when experiencing lower levels of trust in their relationship and that these associations would be stronger among those higher in attachment anxiety. A series of multiple regression models testing moderation were evaluated by testing the interaction between trust and attachment anxiety on all three types of jealousy and both types of perpetration. Trust, anxious attachment, and avoidant attachment were mean centered to facilitate interpretation of the interactions. In all analyses, gender and attachment avoidance were included as covariates. Separate analyses were performed for each of the five outcomes, and results are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Interactions Between Trust and Attachment Anxiety Predicting Three Types of Jealousy

| Outcome | Predictor | B | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive jealousy | Trust | −.285 | −5.43 | <.001 | −.388 | −.181 |

| Attachment anxiety | .197 | 4.62 | <.001 | .113 | .281 | |

| Attachment avoidance | .021 | 0.39 | .695 | −.086 | .129 | |

| Gender | −.088 | −0.70 | .482 | −.334 | .158 | |

| Trust × Attachment Anxiety | −.096 | −2.41 | .017 | −.174 | −.018 | |

| Behavioral jealousy | Trust | −.102 | −2.26 | .025 | −.191 | −.013 |

| Attachment anxiety | .225 | 6.12 | <.001 | .153 | .298 | |

| Attachment avoidance | .028 | 0.59 | .554 | −.065 | .120 | |

| Gender | .179 | 1.66 | .098 | −.034 | .391 | |

| Trust × Attachment Anxiety | −.070 | −2.01 | .045 | −.137 | −.002 | |

| Emotional jealousy | Trust | .100 | 1.67 | .096 | −.018 | .217 |

| Attachment anxiety | .128 | 2.61 | .010 | .032 | .225 | |

| Attachment avoidance | .068 | 1.09 | .276 | −.055 | .191 | |

| Gender | .331 | 2.32 | .021 | .050 | .611 | |

| Trust × Attachment Anxiety | −.039 | −0.85 | .398 | −.128 | .051 | |

| Physical abuse | Trust | −.100 | −2.29 | .023 | −.186 | −.014 |

| Attachment anxiety | .116 | 3.28 | .001 | .047 | .186 | |

| Attachment avoidance | −.015 | −0.327 | .744 | −.104 | .074 | |

| Gender | .055 | 0.53 | .595 | −.149 | .260 | |

| Trust × Attachment Anxiety | −.047 | −1.43 | .155 | −.112 | .018 | |

| Psychological abuse | Trust | −.126 | −2.77 | .006 | −.216 | −.037 |

| Attachment anxiety | .170 | 4.59 | <.001 | .097 | .243 | |

| Attachment avoidance | −.016 | −0.34 | .736 | −.109 | .077 | |

| Gender | .008 | 0.07 | .943 | −.206 | .222 | |

| Trust × Attachment Anxiety | −.071 | −2.05 | .042 | −.139 | −.003 |

Note. Significant interaction results are bolded. LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval.

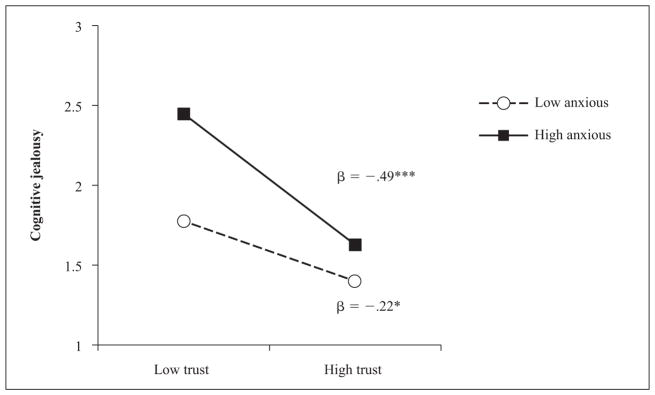

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, significant negative associations emerged between trust and the two predicted jealousy subscales: Cognitive Jealousy and Behavioral Jealousy. In support of Hypothesis 2, there were significant interactions between trust and anxious attachment in predicting cognitive and behavioral jealousy. First, trust and attachment anxiety interacted to predict cognitive jealousy, b = −.095, t(254) = −2.36, p = .019. Tests of simple slopes evaluated the association between trust and cognitive jealousy at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of attachment anxiety (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Results are presented graphically in Figure 1. Simple slopes analyses revealed that trust was negatively associated with jealousy at high levels of attachment anxiety, b = −.392, β = −.487, t(254) = −5.92, p < .001, and at low levels of attachment anxiety, b = −.180, β = −.220, t(254) = −2.49, p = .014. In other words, distrust in one’s partner was associated with experiencing cognitive jealousy at low and high levels of anxious attachment but more strongly among those at higher levels of anxious attachment.

Figure 1.

Trust and anxious attachment interact to predict cognitive jealousy. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

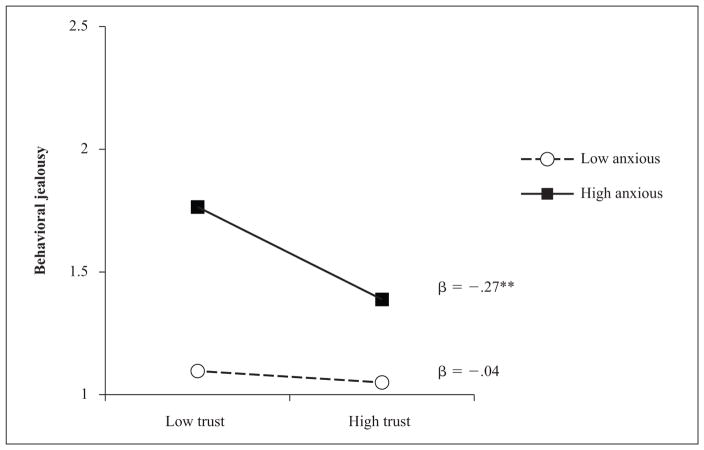

As expected, anxious attachment also moderated the association between trust and behavioral jealousy, b = −.070, t(254) = −2.04, p = .043. The interaction is graphed in Figure 2. Tests of simple slopes showed that for those high in attachment anxiety, not trusting their partner was associated with increases in behavioral jealousy, b = −.180, β = −.270, t(254) = −3.16, p = .002, whereas there was no association between trust and behavioral jealousy for individuals low in attachment anxiety, b = −.022, β = −.041, t(254) = −0.36, p = .720.

Figure 2.

Trust and anxious attachment interact to predict behavioral jealousy. **p < .01.

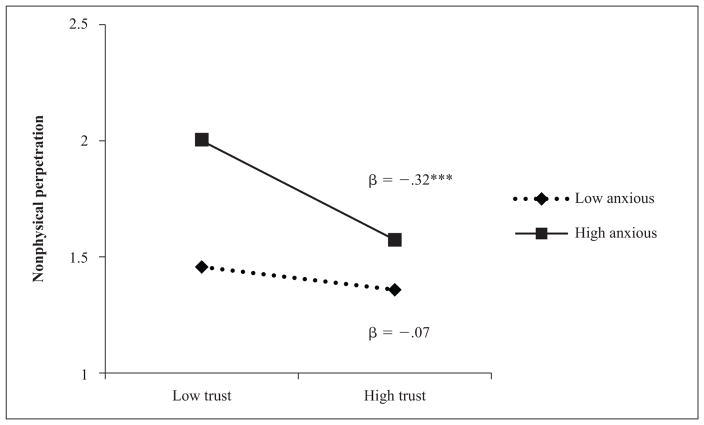

We also evaluated associations between trust, anxious attachment, and physical and psychological partner abuse. In support of Hypothesis 3, main effects suggested that trust was negatively associated with both types of partner abuse. Furthermore, attachment anxiety was tested as a moderator of the association between trust and partner abuse (Hypothesis 4). Consistent with hypotheses, trust interacted with anxious attachment to predict nonphysical abuse, b = −.071, t(254) = −2.05, p = .042. Results are presented in Figure 3. Simple slopes analyses showed a similar pattern as with behavioral jealousy; trust was not associated with psychological abuse for individuals lower in attachment anxiety, b = −.047, β = −.073, t(254) = −0.75, p = .451, whereas trust was negatively associated with abuse for anxious individuals, b = −.206, β = −.320, t(254) = −3.58, p < .001.

Figure 3.

Trust and anxious attachment interact to predict nonphysical perpetration. ***p < .001.

In summary, results suggested that distrust was associated with higher levels of jealous cognitions and behaviors and both types of partner abuse. Although stronger for anxious individuals, distrust was associated with jealous cognitions at all levels of attachment anxiety. Distrust was only associated with jealous behaviors (e.g., snooping) and with psychological abuse among anxious individuals.

Supplementary Analyses

Analyses were performed to examine whether avoidant attachment also interacted with trust to predict jealousy and partner abuse. The interaction was not significant in four of five outcomes (all p > .20). An interaction emerged between trust and avoidant attachment in predicting cognitive jealousy, b = −.131, t(254) = −2.80, p = .005. Tests of simple slopes revealed consistent results to that of anxious attachment and cognitive jealousy. Specifically, the association between trust and cognitive jealousy was stronger at higher levels of avoidant attachment, b = −.398, β = −.493, t(254) = −6.25, p < .001, than at lower levels of avoidant attachment, b = −.128, β = −.158, t(254) = −1.61, p = .109.

DISCUSSION

The present research illustrates the importance of trust in relationships and, more specifically, presents evidence that lack of trust has cascading effects on partners’ cognition and behavior. Furthermore, this research is among the first to indicate that trust-related issues may be particularly problematic among individuals who are higher in anxious attachment. The overall pattern of findings indicates that trust in one’s partner is associated with fewer thoughts and concerns that one’s partner may be romantically interested in someone else, less monitoring of one’s partner’s behaviors and belongings, and lower levels of psychological abuse. Conversely, findings suggest that distrust is associated with more cognitive jealousy, particularly among those who felt less secure in relationships (i.e., anxious individuals). Furthermore, distrust was only associated with behavioral jealousy and nonphysical abuse among anxious individuals. These findings suggest that jealousy may be a natural result of the subjective experience of needing more (higher anxious attachment) but receiving less (lower trust) from one’s partner.

Several interesting findings emerged regarding the different types of jealousy. Behavioral jealousy appeared to be the most problematic because it involves behaviors that are not typically perceived as normative or acceptable. The associations between trust and cognitive jealousy, on the other hand, were evident for those at low and high anxious attachment. This suggests that it may be more natural to experience cognitions associated with jealousy when experiencing lower levels of trust in one’s partner, but it is less natural to act on those thoughts and feelings (e.g., searching through text messages, spying). Consistent with the present research, other recent research has shown that anxious attachment was associated with higher levels of Facebook jealousy, and this was partially mediated by trust (Marshall et al., 2013). Furthermore, anxious attachment was associated with negative partner-directed behaviors, such as heightened surveillance of one’s partner’s activities on Facebook, which was mediated by jealousy. The current research provides an extension by examining how distrust is associated with three types of jealousy and two types of partner abuse for anxious and avoidant individuals.

In general, a loss of trust can negatively bias inferences regarding partner behaviors (Campbell et al., 2010; Murray, Bellavia, Rose, & Griffin, 2003). The overall pattern of findings here suggests that this is more extreme among those who are anxiously attached. For these individuals, fear of abandonment and insecurity in one’s relationship elicits a tendency to seek information. Anxiously attached individuals are less likely to trust others in general and may chronically make suspicious attributions; they are also more sensitive to rejection cues and also more likely to snoop on their partner. Thus, a lack of trust in the partner combined with anxious attachment may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies that serve to reinforce maladaptive beliefs and expectations about the partner’s level of trustworthiness. To the extent that an individual responds to their partner in a hypersensitive, defensive, and destructive manner on a perceived negative trust experience, they may actually emotionally distance themselves from their partner, which encourages the very experience the anxious person is trying to avoid (lower satisfaction and intimacy, possible dissolution of the relationship). In some ways, this seems inevitable, considering the likely conversations that might follow when one discovers his or her partner going through their wallet, purse, or cell phone. At best, this will likely create disharmony and ill feelings in the recognition that one is not trusted. Moreover, partner expressions of offense at being monitored may be perceived by the suspicious partner as confirmation of justification for suspicion.

The results also showed that lower trust and higher attachment anxiety were associated with increased psychological abuse. Thus, although distrust may work as a warning sign of potential partner abuse, only some individuals, such as those who are sensitive to rejection from their partner and who go so far as to engage in various behavioral expression of their insecurity (e.g., snooping through their partner’s belongings, keeping track of their whereabouts), engage in such relationship-destructive behaviors as psychological abuse.

These results may be understood in the context of cognitive resources. Previous research has found that for secure individuals, the relational goal of intimacy trumped the intrapersonal goals of security and control (Mikulincer, 1998b; Mikulincer & Nachshon, 1991). The authors suggest that perhaps secure individuals’ fulfillment of the need for a secure base made available free additional cognitive resources, which could then be used toward nurturing the relationship in a nondefensive, caring way. Conversely, anxious individuals’ propensity to self-protect may ultimately serve to harm their relationship, both through the very mechanisms they are using (e.g., snooping, partner abuse) and the subsequent distance created between themselves and their partner.

Finally, results were performed with avoidant attachment as a moderator. Although nonsignificant in four of five models, trust interacted with avoidant attachment to predict cognitive jealousy, suggesting that distrusting one’s partner was more strongly associated with experiencing jealous thoughts among avoidant individuals. Similar to anxious attachment, however, higher cognitive jealousy accompanied distrust at both low and high levels of attachment avoidance. Taken with the attachment anxiety findings, these results suggest that jealous thoughts are more likely to occur among insecure individuals, although there are clear differences regarding behavioral responses to jealousy between those who are anxiously and avoidantly attached. Although the interaction with avoidant attachment was not predicted, it is not inconsistent with previous research. Mikulincer (1998b) found that avoidant individuals endorsed control as a trust-related goal, which raises questions about whether these individuals might also be prone to experiencing jealous emotions when distrust arises.

IMPLICATIONS

These findings have practical implications for evaluating one’s relationship, ideally in evaluating an early relationship’s potential for endurance. Evidence of attachment anxiety or unfounded instances of distrust are likely warning signs of negative and potentially abusive interactions to come. Repeated questions about one’s whereabouts, a desire to see phone texts, driving by one’s workplace, or other expressions of thinking about the partner should be perceived as problematic indicators and may be a suitable cue for terminating the relationship. In a therapy context, a focus on enhancing trust and understanding the consequences of distrust may be beneficial for couples experiencing jealousy or abuse.

Likewise, the present findings also offer guidance in evaluating one’s own relationship perspectives. Instances of closely monitoring one’s partner may be seen as a signal for the need to reevaluate one’s feelings about the partner and about relationships more generally. Although further empirical evidence is needed, snooping on a partner may more powerfully represent the snooper than the partner and, in the absence of definitive justification for not trusting the partner, suggests a need to consider the sequela of chronic distrust. Although individuals who go through their partner’s belongings are not doing so with the intent to harm the relationship, clarifying the harmful consequences of doing so (for both themselves and their partner) may provide insight into how their behavior, intended to self-protect, ultimately damages the relationship and increases the likelihood of additional problems and relationship dissolution.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The present findings should be considered in the light of several limitations. The cross-sectional data precludes the ability to make causal conclusions or examine changes in jealousy and/or partner abuse over time. Because it is possible that trust fluctuates over time as a function of partner behavior, longitudinal data would also help in disentangling the temporal ordering of these variables. The sample included most females, which may limit generalizability (although we did not find gender differences, suggesting that this may be a minor concern). In addition, the sample was composed of individuals who were in relationships of longer duration than is typically found in college samples. Moreover, the sample consists of undergraduate students, which also limits generalizability of the findings.

The present research only examined variables from one relationship partner. Future research would benefit from incorporating a dyadic perspective and considering both partners perspectives on trust, jealousy, and abuse within the relationship. This would yield rich data that would also help disentangle temporal associations. It might also help distinguish distrust that is unjustified versus accurate perceptions of a partner’s unfaithfulness. The dynamics of distrusting a partner who actually is cheating or being unfaithful is a question that was not considered in the present research but would be of considerable interest.

Our findings are consistent with previous work showing that jealousy is usually negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (Guerrero & Eloy, 1992), especially when partners communicate jealousy in negative, hurtful, or damaging ways (Andersen et al., 1995). Furthermore, recent research showed that insecure attachment was associated with lower marital relationship quality for both partners, and this was mediated by lower levels of trust (Givertz et al., 2013). Nevertheless, jealousy may have positive and negative facets (DiBello, Neighbors, Rodriguez, & Lindgren, 2014): positive facets representing commitment to one’s relationship (e.g., experiencing distress on imagining his or her partner engaging in sexual relations with another person) and negative facets representing a desire to control (e.g., excessive and unwarranted concern about one’s partner’s behaviors and whereabouts). Although the current research focused on the negative aspects of jealousy and found that behavioral jealousy was particularly negative, additional research might benefit from more precisely identifying the boundaries between expressing commitment and concern for one’s partner and being jealous and controlling.

In conclusion, the present research offers a unique examination of associations among trust, anxious attachment, jealousy, and perpetration of partner abuse. Results suggest that distrust in one’s partner was associated with cognitive and behavioral manifestations of jealousy as well as partner abuse. Whereas distrust was associated with jealous thoughts at all levels of attachment anxiety, distrust predicted partner surveillance behaviors and psychological abuse only among anxious individuals. These results suggest that trust, attachment, and what constitutes acceptable boundaries for the couple should be critical points of discussion in a couples’ therapy context where surveillance behaviors and partner abuse are present.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant F31AA020442.

References

- Andersen PA, Eloy SV, Guerrero LK, Spitzberg BH. Romantic jealousy and relational satisfaction: A look at the impact of jealousy experience and expression. Communication Reports. 1995;8:77–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08934219509367613. [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, Samios L, O’Leary KD. Prevalence and correlates of physical aggression during courtship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1987;2:82–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/088626087002001005. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Reed JT, Goodfriend W, Agnew CR. Relationship perceptions and persistence: Do fluctuations in perceived partner commitment undermine dating relationships? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1045–1065. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylor B, Dainton M. Antecedents in romantic jealousy experience, expression, and goals. Western Journal of Communication. 2001;65:370–391. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan JL. Experiencing and communicating romantic jealousy: Questioning the investment model. Southern Communication Journal. 2008;73:42–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10417940701815626. [Google Scholar]

- Boden J, Fergusson D, Horwood L. Alcohol misuse and violent behavior: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;122:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health outcomes in women with physical and sexual intimate partner violence exposure. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:987–997. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, Zdaniuk B. Adult attachment styles and aggressive behavior within dating relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Volume 1: Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;34:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Shaver P. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP. Personality, birth order, and attachment styles as related to various types of jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;23:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Dijkstra P. Evidence for a sex-based rival oriented mechanism: Jealousy as a function of a rival’s physical attractiveness and dominance in a homosexual sample. Personal Relationships. 2001;8:391–406. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Dijkstra P. Temptations and threat: Extradyadic relations and jealousy. In: Vangelisti AL, Perlman D, editors. The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 533–555. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. The dangerous passion: Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. New York, NY: Free Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Simpson JA, Boldry JG, Kashy DA. Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:510–531. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Simpson JA, Boldry JG, Rubin H. Trust, variability in relationship evaluations, and relationship processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:14–31. doi: 10.1037/a0019714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Lemay EP. Close relationships. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. 5. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Wiley; 2010. pp. 898–940. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL. Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:810– 832. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KE, Ace A, Andra M. Stalking perpetrators and psychological maltreatment of partners: Anger-jealousy, attachment insecurity, need for control, and break-up context. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:407–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBello AM, Neighbors C, Rodriguez LM, Lindgren K. Coping with jealousy: The association between maladaptive aspects of jealousy and drinking problems are mediated by drinking to cope. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Barelds DP, Groothof HA. An inventory and update of jealousy-evoking partner behaviors in modern society. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2010;17:329–345. doi: 10.1002/cpp.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Buunk BP. Sex differences in the jealousy-evoking effect of rival characteristics. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;32:829–852. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.125. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Bradley RG, Helff CM, Laughlin JE. A model for predicting dating violence: Anxious attachment, angry temperament, and need for relationship control. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:35–47. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.35.33639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner JW, Hudson WW. Non-Physical Abuse of Partner Scale (NPAPS) In: Fisher J, Corcoran K, editors. Measures for clinical practice: A sourcebook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 149–150. [Google Scholar]

- Givertz M, Woszidlo A, Segrin C, Knutson K. Direct and indirect effects of attachment orientation on relationship quality and loneliness in married couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2013;30:1096–1120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407513482445. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley B, Lopez FG. Psychological abuse perpetration in college dating relationships: Contributions of gender, stress, and adult attachment orientations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:204–218. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260509334404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK. Attachment-style differences in the experience and expression of romantic jealousy. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK, Afifi WA. Communicative responses to jealousy as a function of self-esteem and relationship maintenance goals: A test of Bryson’s dual motivation model. Communication Reports. 1998;11:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK, Andersen PA, Jorgensen PF, Spitzberg BH, Eloy SV. Coping with the green-eyed monster: Conceptualizing and measuring communicative responses to romantic jealousy. Western Journal of Communication. 1995;59:270–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10570319509374523. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK, Eloy SV. Relational satisfaction and jealousy across marital types. Communication Reports. 1992;5:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Spriggs AL, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization from adolescence to young adulthood in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen GL. Jealousy: Its conceptualization, measurement, and integration within family stress theory. In: Salovey P, editor. The psychology of jealousy and envy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 252–272. [Google Scholar]

- Harris C. A review of sex differences in sexual jealousy, including self-report data, psychophysiological responses, interpersonal violence, and morbid jealousy. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:102–128. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0702_102-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychological Inquiry. 1994;5:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Henton J, Cate R, Koval J, Lloyd S, Christopher S. Romance and violence in dating relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1983;4:467–478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/019251383004003004. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JG, Rempel JK. Trust in close relationships. In: Hendrick C, editor. Close relationships. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1989. pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Meehan JC, Herron K, Rehman U, Stuart GL. Do subtypes of martially violent men continue to differ over time? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:728–740. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA, Davis KE. Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:502–512. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, McCullars A, Misra TA. Motivations for men and women’s intimate partner violence perpetration: A comprehensive review. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:429–468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.4.429. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay EP, Jr, Clark MS, Feeney BC. Projection of responsiveness to needs and the construction of satisfying communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:834–853. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall TC, Bejanyan K, Di Castro G, Lee RA. Attachment styles as predictors of Facebook-related jealousy and surveillance in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 2013;20:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mayseless O. Adult attachment patterns and courtship violence. Family Relations. 1991;40:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. Adult attachment style and individual differences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998a;74:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. Attachment working models and the sense of trust: An exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998b;74:1209–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Erev I. Attachment style and the structure of romantic love. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;30:273–291. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1991.tb00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Nachshon O. Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 35. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MS. No visible wounds: Identifying nonphysical abuse of women by their men. New York, NY: Random House; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rivas MJ, Graña J, O’Leary K, González M. Aggression in adolescent dating relationships: Prevalence, justification, and health consequences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Bellavia GM, Rose P, Griffin DW. Once hurt, twice hurtful: How perceived regard regulates daily marital interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:126–147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Derrick JL, Leder S, Holmes JG. Balancing connectedness and self-protection goals in close relationships: A levels-of-processing perspective on risk regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:429–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.429. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Collins NL. Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:641–666. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: How perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:478–498. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW, Bellavia G, Rose P. The mismeasure of love: How self-doubt contaminates relationship beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:423–436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167201274004. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Pinkus RT, Holmes JG, Harris B, Gomillion S, Aloni M, … Leder S. Signaling when (and when not) to be cautious and self-protective: Impulsive and reflective trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:485–502. doi: 10.1037/a0023233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe NK, Brockopp K, Chew E. Teen dating violence. Social Work. 1986;31:465–468. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:400–414. [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Garcia M, Pickett SM. Female-perpetrated intimate partner violence and romantic attachment style in a college student sample. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:287–302. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SM, Wong PTP. Multidimensional jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1989;6:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Clark MS, Holmes JG. Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness. In: Mashek DJ, Aron AP, editors. Handbook of closeness and intimacy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG. How do I trust thee? Psychology Today. 1986;20(2):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG, Zanna MP. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:95–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rholes SW, Simpson JA. Adult attachment: Theory, research and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts N, Noller P. The associations between adult attachment and couple violence: The role of communication patterns and relationship satisfaction. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 317–350. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/intimate-partner-violence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpsteen DJ, Kirkpatrick LA. Romantic jealousy and adult romantic attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:627–640. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Hazan C. Adult romantic attachment: Theory and evidence. In: Perlman D, Jones W, editors. Advances in personal relationships. Vol. 4. London, United Kingdom: Kingsley; 1993. pp. 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sidelinger RJ, Booth-Butterfield M. Mate value discrepancy as a predictor of forgiveness and jealousy in romantic relationships. Communication Quarterly. 2007;55:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:971–980. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. Foundations of interpersonal trust. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007a. pp. 587–607. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. Psychological foundations of trust. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007b;16:264–268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00517.x. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, Pirog-Good MA. Violence in dating relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1987;50:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Gender symmetry and mutuality in perpetration of clinical-level partner violence: Empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen MM, Klipfel KM, Mata AD, Schinka KC, Claxton SE, Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. Cross-lagged effects between intimate partner violence victimization and suicidality from adolescence into adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkers CW, Finkenauer C, Hawk ST. Why do close partners snoop? Predictors of intrusive behavior in newlywed couples. Personal Relationships. 2011;18:110–124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01314.x. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM. Testing a typology of batterers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:658–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Vogel DL. The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)–Short Form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88:187–204. doi: 10.1080/00223890701268041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler ML. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Syracuse University; NY: 2002. Effect of attachment and threat of abandonment on intimacy: Anger, aggressive behavior, and attributional style. [Google Scholar]

- White GL, Mullen PE. Jealousy: Theory, research, and clinical strategies. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Koss MP. Courtship violence: incidence in a national sample of higher education students. Violence and Victims. 1991;6:247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]