Abstract

This paper provides new evidence on parent and child reporting of corporal punishment, drawing on data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a birth cohort study of families in 20 medium to large US cities. In separate interviews, 9 year olds and their mothers (N=1,180 families) were asked about the frequency of corporal punishment in the past year. Mothers and children were asked questions with slightly different response categorize which are harmonized in our analysis. Overall, children reported more high frequency corporal punishment (spanking or other physical punishment more than 10 times per year) than their mothers did; this discrepancy was seen in both African-American and Hispanic families (but not White families), and was evident for both boys and girls. These results suggest that reporting of frequency of corporal punishment is sensitive to the identity of the reporter and that in particular child reports may reveal more high frequency punishment than maternal reports do. However, predictors of high frequency punishment were similar regardless of reporter identity; in both cases, risk of high frequency punishment was higher when the child was African-American or had high previous levels of behavior problems.

Keywords: corporal punishment, child reports, parent reports, Conflict Tactic Scales

Child maltreatment is notoriously difficult to measure. Administrative data capture only those children who have come to the attention of Child Protective Services (CPS) and may therefore be biased by the myriad factors that influence which families and children are reported (Drake, Lee, & Jonson-Reid, 2009; Waldfogel, 2009). Yet gathering data from population samples is also challenging. Asking questions about maltreatment is sensitive and parents may not report accurately on their own behavior. For these reasons, information gathered from first-hand reports of children may be particularly informative.

This paper reports results from questions about corporal punishment asked of both mothers and their 9-year-old children, drawing on data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a large birth cohort study in 20 medium to large US cities. While corporal punishment is not synonymous with maltreatment, families in which children are being physically disciplined at high frequency may be those where children are also at risk of physical abuse; indeed, previous research has found that mothers reporting very frequent corporal punishment of their 9 year olds were significantly more likely to have been reported to CPS (Brooks-Gunn, Schneider, & Waldfogel, 2013). This paper therefore focuses on high frequency corporal punishment – where children are being spanked or administered other physical punishment more than 10 times per year. Our goal is twofold: 1) to determine whether the reported frequency of corporal punishment varies depending on the identity of the reporter, and, if so, whether such variation differs by race/ethnicity and gender; and 2) to determine whether the predictors of frequent corporal punishment vary depending on the identity of the reporter.

The present study adds to a small existing literature on variation in reporting of corporal punishment between children and parents. The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), the measure used in this study, was developed to capture parent reports of corporal punishment as well as abuse and neglect. It was later revised (Conflict Tactics Scale Parent-Child; CTSPC) in an effort to better capture the relationships between caregivers and children (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Although the best available measure of parent-child conflict, the CTSPC is potentially limited in its ability to identify child maltreatment because it relies on caregivers’ reports of their own behavior (Straus, 2007). A number of studies have attempted to better estimate child maltreatment by comparing data on maltreatment from different sources, including clinical observers and administrative records (Kaufman, Jones, Stieglitz, Vitulano, & Mannarino, 1994; McGee, Wolfe, Yuen, Wilson, Carnochan, 1995) and mothers and fathers (Lee, Lansford, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 2012). A few studies have used longitudinal data to compare prospective parent reports of maltreatment with retrospective adolescent reports (Shafer, Huston, & Egeland, 2008; Tajima, Herrenkohl, Huang, & Whitney, 2004). Particularly relevant for our study are two studies that directly compared contemporaneous parent and child reports. One study in Hong Kong found low levels of agreement about maltreatment between parents and children (Chan, 2012); another study in the U.S. found that children reported much higher levels of violence than mothers did (Kolko, Kazdin, & Tay, 1996). Our work also builds on studies of child-parent discrepancies in reports of other phenomena, such as child behavior problems or child mental health, generally finding that children report more problems than their parents do, although children are also are more likely to report no problems (see e.g. Mourizi, Gershoff, & Aber, 2012; Pahres, Compas, & Howell, 1989; Seiffge-Krenke & Kollmar, 1998; Verhulst & van derEnde, 1992).

METHOD

Data

Data come from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), which captures the experiences of parents with births between 1998 and 2000. Mothers and fathers were interviewed in the hospital or shortly after the birth of a child in 20 cities in 15 U.S. states. When weighted, the data are representative of births in U.S. cities with populations of 200,000 or more people. The respondents were re-interviewed by telephone or in-home interview when the children were 1, 3, 5, and 9 years old (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel & McLanahan 2001). Importantly, children at the 9-year survey were interviewed and asked to report on a wide range of their own and their parents’ behaviors and interactions. The present study (N=1,180) includes information on mothers’ use of corporal punishment with their 9-year old child, as reported by both mother and child.

Measures

Corporal Punishment

At the 9-year survey mothers were asked a series of 14 questions about their positive and harsh parenting practices. Questions about harsh parenting were interspersed with questions about positive parenting. Three questions were asked about how many times in the past year (never, 1–2 times, 3–10 times, 11 to 20 times, or more than 20 times) mothers had spanked, hit, or slapped their child; frequency of corporal punishment was coded based on the highest category across the three questions. Similarly, as part of a series of three questions about positive and harsh parenting practices, children were asked a single question about how frequently in the past year (never, less than once per month, once to a few times per month, a few times a week) their mother had spanked, hit, or slapped them. Because mother and child questions had slightly different response categories, we harmonized them by using the following categories: never; 1–2 times per year (or less than once per month); 3–10 times per year (or once to a few times per month); and more than 10 times per year (or a few times a week).

Other Variables

Scholars have identified a number of predictors of the risk for child maltreatment and Child Protective Services involvement. Risk factors are often conceptualized as occurring on four levels – individual, family, community, and socio-cultural (Belsky, 1993; McDaniel & Slack, 2005) with the probability of risk being cumulative in nature (MacKenzie, Kotch, & Lee, 2011, MacKenzie, Kotch, Lee, Augsberger & Hutto, 2011). Among the individual predictors a robust literature has demonstrated that children from low-income families are at increased risk of experiencing maltreatment (Lee & George, 1999; Paxson & Waldfogel, 1999). In addition, factors like maternal age, educational attainment (Slack, Holl, Yoo, & Bolger, 2004), depression (Conron, Beardslee, Koenen, Buka, & Gortmaker, 2009), family size, maternal employment, maternal drug and alcohol use, and marital status have all been shown to be significant predictors of child maltreatment (Brayden, Altemeier, Tucker, Dietrich, & Vietze, 1992; Dubowitz, Kim, Black, Weisbart, Semiatin, & Magder, 2011; Slack et al., 2004). A wide range of research has also shown that parental stress and child problem behaviors are associated with child maltreatment (Gershoff, 2002). Last, research has indicated that Black families are more likely to be reported to Child Protective Services (Wildeman, Emanual, Leventhal, Putnam-Hornstein, Waldfogel, & Lee, 2014) and that this may be because Black families may be more visible to mandated reporters (Drake & Zuravin, 1998). To that end, we control for a number of predictors of child maltreatment from across these four groups.

Predictors of frequency of corporal punishment examined include a broad range of mother and child factors. Mother characteristics include: race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, white), immigrant status, education (less than high school, high school, some college, college or more, poverty status (percent of the Federal Poverty Line for relevant family size), current marital status (married, cohabiting, single), employment status, age, whether the focal child was her first child, history of depression, report of neighborhood violence, drug/alcohol use, and self reported levels of parenting stress (“being a parent is harder than I thought it would be,” “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent,” “taking care of child is more work than pleasure,” “I feel worn out from raising a family”). Child characteristics include: age, birth weight, externalizing behaviors (as reported by mother), and child’s teacher’s report of child’s problem behaviors at the 9-year survey.

Analytic approach

To address the first research question, frequencies of corporal punishment as reported by mother and child are calculated, both for the overall sample and for the sample disaggregated by race/ethnicity and child gender. To address the second research question, the relative risk of each level of corporal punishment, as compared to no corporal punishment, is estimated using multinomial logistic regression for both mother and child reports.

RESULTS

Frequency of Corporal Punishment in Mother vs. Child Reports

Overall, children report more high frequency corporal punishment (spanking, hitting, slapping) than mothers do. As shown in Table 1, only 7% of mothers report using corporal punishment more than 10 times per year, but 15% of children report receiving corporal punishment that frequently (different from each other p < 0.001). However, more children than mothers also report that corporal punishment is never used (46% of families according to child reports, vs. 36% according to maternal reports) (different from each other p < 0.001). Although mothers and children were asked questions with slightly different response categories, through collapsing categories we were able to harmonize the variables so that they were comparable.

Table 1.

Mother and child reports of maternal corporal punishment.

| Child reports | Mother reports | |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 46.3% (0.01) | 36.2% (0.01) |

| 1–2 per year | 21.4% (0.01) | 28.7% (0.01) |

| 3–10 per year | 17.3% (0.01) | 28% (0.01) |

| > 10 per year | 15% (0.01) | 7.1% (0.01) |

|

| ||

| N | 1,180 | |

Note: Standard errors in parentheses

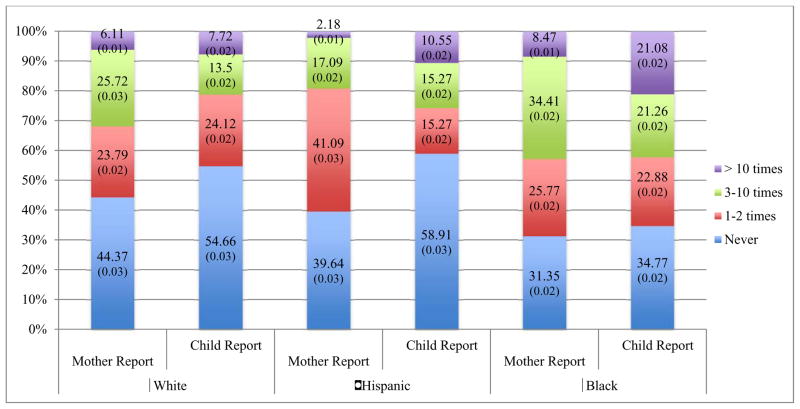

These patterns vary a good deal by race/ethnicity, as shown in Figure 1. White children and mothers largely agree on the frequency of mothers’ corporal punishment, although the children are more likely to report “never” and less likely to report medium frequency than are the mothers. Hispanic children also are more likely than mothers to report “never”, but they are also more likely to report high frequency punishment (more than 10 times per year). African-American children and mothers largely agree on “never” and low levels of corporal punishment, but children report more than twice as much high frequency corporal punishment as mothers. Interestingly, though, if one combines the middle and high frequency categories, then African-American children and mothers largely agree.

Figure 1.

Corporal Punishment by Mother and Child Report*

*Standard errors in parentheses

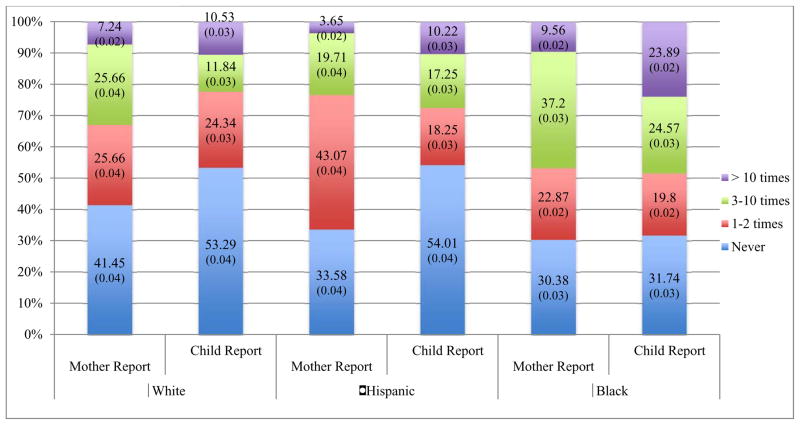

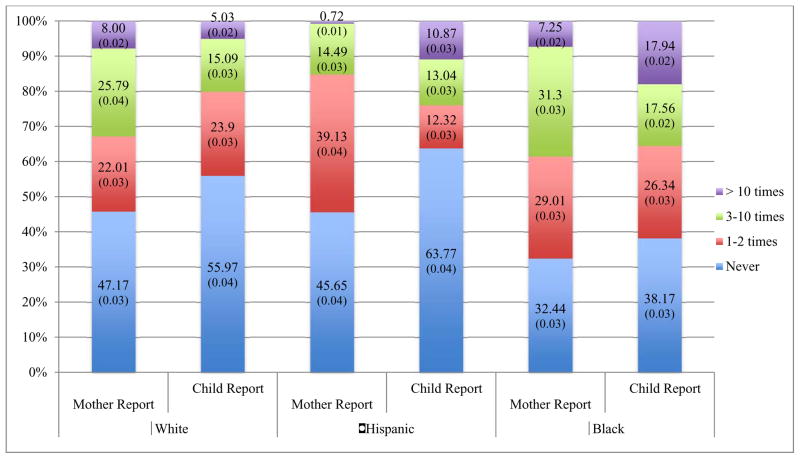

Figures 2 and 3 break out the patterns shown in Figure 1 by child gender. Overall, boys report slightly more corporal punishment than girls, but otherwise the general patterns from Figure 1 are present in Figures 2 and 3. Most notably, in both Hispanic and African-American families, both boys and girls are more likely to report high frequency corporal punishment than are mothers.

Figure 2.

Mother and Child Report of Corporal Punishment Among Boys by Race/Ethnicity*

*Standard errors in parentheses

Figure 3.

Mother and Child Report of Corporal Punishment Among Girls by Race/Ethnicity*

*Standard errors in parentheses

Predictors of High Frequency Corporal Punishment

Given these discrepancies in reported frequency, it is of interest to examine whether similar factors predict high frequency corporal punishment when reported by children as opposed to mothers. Is the high frequency punishment reported by children a different phenomenon than that reported by mothers? The results in Table 2 indicate that in general, similar factors predict high frequency corporal punishment regardless of whether it is reported by a mother or child. In these multinomial logistic regression results, significant relative risk ratios indicate factors that are associated with significantly elevated likelihood of being in a more frequent punishment category as opposed to the reference category (never). In both the mother-reported and child-reported analyses, being African-American and having higher levels of child externalizing problems are significant and strong predictors of high frequency corporal punishment for 9 year olds. The effect of being African-American is larger in the child-reported model than the mother-reported one, reflecting the greater likelihood of African-American children as opposed to mothers to report in that category. There are also some factors (e.g. maternal reports of parenting stress and drug use) that are uniquely significant in the mother-reported models, but overall the patterns are of generally consistent predictors across the two types of reporters. (Results from models run separately by race/ethnicity and gender, available on request, are similar).

Table 2.

Predictors of Mother and Child Reports of Maternal Corporal Punishment: Relative Risks Ratios from Multinomial Regressions

| Mother Self Report | Child Self Report | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 3 Items from Conflct Tactic in the last year | 3 Items from Conflct Tactic in the last year | |||||||

| Never | 1–2 times | 3–10 times | > 10 times | Never | 1–2 times | 3–10 times | > 10 times | |

|

|

|

|||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | ref. | 1.206 | 1.901** | 2.214* | ref. | 1.502+ | 2.293*** | 3.321*** |

| Hispanic | ref. | 1.423 | 0.728 | 0.481 | ref. | 0.522* | 0.935 | 1.177 |

| Immigrant | ref. | 1.887* | 0.946 | 1.073 | ref. | 2.790*** | 1.468 | 2.437* |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than HS | ref. | 1.319 | 1.290 | 1.326 | ref. | 0.940 | 0.905 | 1.679* |

| Some college | ref. | 1.422+ | 1.191 | 0.915 | ref. | 1.194 | 1.101 | 1.334 |

| College or more | ref. | 1.422 | 1.497 | 0.980 | ref. | 0.860 | 0.556 | 0.954 |

| Poverty (FPL) | ||||||||

| 0–49% | ref. | 0.524* | 0.410** | 0.240** | ref. | 0.476* | 0.575+ | 0.692 |

| 50–99% | ref. | 0.863 | 0.982 | 0.266* | ref. | 0.755 | 0.666 | 0.842 |

| 100–199% | ref. | 1.176 | 1.787* | 1.168 | 0.850 | 0.594* | 1.234 | |

| Marital status (9-Year) | ||||||||

| Cohabiting | ref. | 1.508 | 0.761 | 0.341 | ref. | 1.011 | 1.169 | 1.114 |

| Single | ref. | 1.332 | 0.864 | 0.560+ | ref. | 1.030 | 1.272 | 0.749 |

| Mother characteristics | ||||||||

| Mother age | ref. | 0.992 | 0.972+ | 0.982 | ref. | 0.968+ | 0.987 | 0.962+ |

| First birth | ref. | 1.108 | 1.230 | 1.457 | ref. | 0.797 | 1.023 | 0.946 |

| Ever depressed | ref. | 0.886 | 1.010 | 1.270 | ref. | 1.040 | 1.050 | 0.833 |

| Parenting stress | ref. | 1.040 | 1.077* | 1.198** | ref. | 1.010 | 1.004 | 1.049 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Child age | ref. | 0.954* | 0.951* | 0.939 | ref. | 1.012 | 0.930** | 0.976 |

| Low birth weight | ref. | 1.616+ | 0.879 | 0.605 | ref. | 1.329 | 0.844 | 1.279 |

| Child male | ref. | 0.953 | 1.024 | 1.233 | ref. | 0.996 | 1.340 | 1.393+ |

| Externalizing behaviors | ref. | 1.081*** | 1.152*** | 1.189*** | ref. | 1.023 | 1.028+ | 1.061*** |

| Teacher report of problem behaviors | ref. | 1.007 | 1.013 | 1.020 | ref. | 0.996 | 0.994 | 1.007 |

| Risk Factors | ||||||||

| Violent neighborhood | ref. | 1.336 | 1.242 | 1.773 | ref. | 0.576* | 0.795 | 1.054 |

| Mother uses drugs | ref. | 1.516 | 1.270 | 3.150* | ref. | 1.698+ | 0.965 | 1.662 |

| Mother alc. | ref. | 0.837 | 1.124 | 1.380 | ref. | 1.241 | 1.030 | 0.872 |

| Mother employed | ref. | 1.118 | 1.231 | 0.616 | ref. | 0.715+ | 0.639* | 0.743 |

|

| ||||||||

| N | 1180 | |||||||

Notes

p< 0.10,

p<0.05,

p< 0.01,

p<0.001

Includes city fixed effects

We combine the three questions about corporal punishment that were asked of mothers into one question so as to be comparable to the question the children were asked. However, it is possible that particular corporal punishment activities are driving the associations. Because mothers, unlike the children, were asked three separate questions about the frequency with which they spanked, hit, or slapped their child, we are able replicate the analyses in table 2 with each indicator of corporal punishment independently. Overall, we find results that are quite similar to our main model (table 3). However, in these secondary analyses being African-American is not significantly associated with maternal spanking, but it is associated with hitting and slapping.

Table 3.

Predictors of Mother Report of Corporal Punishment: Relative Risks Ratios from Multinomial Regressions

| Spanking | Hitting | Slapping | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Never | 1–2 times | 3–10 times | > 10 times | Never | 1–2 times | 3–10 times | > 10 times | Never | 1–2 times | 3–10 times | > 10 times | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Black | Ref. | 1.016 | 1.007 | 0.925 | Ref. | 2.608*** | 6.110*** | 3.128+ | Ref. | 1.459+ | 3.794*** | 4.385** |

| Hispanic | Ref. | 1.356 | 0.605 | 0.471 | Ref. | 1.658+ | 1.473 | 0.221 | Ref. | 1.516 | 1.255 | 0.813 |

| Immigrant | Ref. | 1.710* | 1.166 | 0.825 | Ref. | 1.509 | 0.963 | 0.581 | Ref. | 1.144 | 0.595 | 1.77 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than HS | Ref. | 1.158 | 1.244 | 0.583 | Ref. | 1.241 | 0.918 | 0.384 | Ref. | 1.087 | 0.893 | 1.065 |

| Some College | Ref. | 1.133 | 1.083 | 0.513 | Ref. | 1.096 | 0.881 | 0.599 | Ref. | 0.953 | 0.917 | 0.436+ |

| College or more | Ref. | 1.054 | 1.11 | 0.589 | Ref. | 1.152 | 1.426 | 0.166+ | Ref. | 0.927 | 1.209 | 0.391 |

| Poverty (FPL) | ||||||||||||

| ’0–40% | Ref. | 0.744 | 0.597 | 0.354+ | Ref. | 0.737 | 0.577 | 0.066**” | Ref. | 0.584+ | 0.421* | 0.319+ |

| 50–100% | Ref. | 1.042 | 1.205 | 0.199* | Ref. | 0.69 | 0.882 | 0.153* | Ref. | 0.685 | 0.632 | 0.283* |

| 100–199% | Ref. | 0.943 | 1.421 | 0.585 | Ref. | 0.941 | 1.358 | 0.575 | Ref. | 0.851 | 1.065 | 0.79 |

| Marital Status (9-Year) | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||||

| Cohabiting | Ref. | 1.213 | 0.371* | 0.093+ | Ref. | 1.445 | 0.373* | 0.444 | Ref. | 1.444 | 0.973 | 0.162 |

| Single | Ref. | 0.944 | 0.754 | 0.708 | Ref. | 1.782** | 1.013 | 0.643 | Ref. | 1.373 | 0.884 | 0.883 |

| Mother characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Mother age | Ref. | 0.98 | 0.977 | 0.946 | Ref. | 1.006 | 0.957* | 0.995 | Ref. | 1.004 | 0.983 | 1.001 |

| First birth | Ref. | 1.044 | 1.417+ | 0.597 | Ref. | 1.134 | 0.886 | 0.786 | Ref. | 1.134 | 1.175 | 1.883 |

| Ever depressed | Ref. | 0.871 | 1.018 | 1.314 | Ref. | 1.176 | 0.893 | 2.172 | Ref. | 0.854 | 1.036 | 1.502 |

| Parenting stress | Ref. | 1.038 | 1.078* | 1.202** | Ref. | 1.028 | 1.026 | 1.237* | Ref. | 1.054+ | 1.129*** | 1.189** |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Child age | Ref. | 0.97 | 0.966 | 0.932 | Ref. | 0.991 | 0.975 | 0.831+ | Ref. | 0.964 | 0.953+ | 0.949 |

| Low birth weight | Ref. | 1.666* | 1.33 | 0.637 | Ref. | 1.198 | 0.981 | 0.865 | Ref. | 1.104 | 0.471* | 0.339+ |

| Child male | Ref. | 0.893 | 0.740+ | 1.311 | Ref. | 1.380+ | 1.287 | 0.968 | Ref. | 1.019 | 1.019 | 0.894 |

| Externalizing behaviors | Ref. | 1.025+ | 1.067*** | 1.107*** | Ref. | 1.049**” | 1.100*** | 1.152*** | Ref. | 1.058*** | 1.103*** | 1.120*** |

| Teacher report of Problem behaviors | Ref. | 1.007 | 1.017+ | 1.022 | Ref. | 0.989 | 1.003 | 1.025 | Ref. | 1 | 1.01 | 1.031* |

| Risk factors | ||||||||||||

| Violent neighborhood | Ref. | 1.251 | 1.292 | 1.46 | Ref. | 0.868 | 1.01 | 1.223 | Ref. | 1.367 | 1.241 | 1.572 |

| Mother uses drugs | Ref. | 1.323 | 1.824+ | 1.722 | Ref. | 0.451+ | 0.82 | 4.336** | Ref. | 1.192 | 1.449 | 3.101* |

| Mother alc. | Ref. | 1.043 | 0.978 | 1.297 | Ref. | 1.134 | 1.153 | 1.051 | Ref. | 1.474+ | 1.671* | 2.527* |

| Mother employed | Ref. | 1.03 | 1.305 | 0.552+ | Ref. | 1.066 | 1.229 | 0.477 | Ref. | 1.057 | 1.064 | 0.814 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| N | 1,180 | |||||||||||

Notes

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Includes city fixed effects

DISCUSSION

Family-level data on frequency of parental corporal punishment are an important source of information about family disciplinary practices and risk for maltreatment. Most such data, however, come from parental reports, which could be biased. This study provides new results from a study that gathered information about high frequency corporal punishment from both mothers and children.

The results indicate that children are more likely to report high frequency corporal punishment than are parents; this is particularly true for African-American and Hispanic children, and holds for both boys and girls within these sub-groups. This result has important implications for research and practice. Administrative data are often seen as under counting the level of child maltreatment that actually occurs. This study indicates that relying exclusively on parent’s self- report may also under count actual levels of corporal punishment and, by extension, possibly also maltreatment. Thus, to the extent possible, researchers and practitioners should try to gather information from children as well as parents. We note that in future research it would be particularly helpful to ensure that the wording of questions posed to parents and children is as similar as possible. One limitation of the current study is that the wording, and number, of the mother and child questions were not identical and thus we had to construct comparable categories with the data available. Future research should explore the importance of asking parents and children the same set of questions.

The results also provide some evidence that children are more likely than mothers to report corporal punishment “never” being used. This pattern is found for both White and Hispanic children (whereas in African-American families, similar shares of children and mothers report “never”). Further research is needed to understand why some children report no corporal punishment when their mothers report at least some, and why this pattern would be found for White and Hispanic children, but not African-American children. Studies on other topics have found that children are more likely than adults to “satisfice,” selecting the first offered response category (Borgers et al., 2003, 2004; Fuchs, 2005) and that children are more likely to select “never” when other categories are detailed numeric frequencies (Smith & Platt, 2013). Children may also be more likely than adults to anchor their responses in recent events, even when asked about the past year (Harel, et al., 1994). Perhaps these phenomena are playing a role here, although it is not clear why they would apply to some groups and not others.

Although children and parents are reporting different frequencies of corporal punishment, in cases where they report high frequency punishment (more than 10 times/year), the predictors are similar. In particular, being African-American is associated with higher risk of high frequency corporal punishment (two times as high in mother-reported data, and three times as high in child-reported data). The child having high levels of behavior problems is also a risk factor, regardless of reporter. So it appears that although mothers and children do not fully agree about when high frequency punishment is occurring, they are reporting it in similar types of families and circumstances. Although we could not test which type of corporal punishment may be driving our results for children, for mothers of the 9-year old children in our survey it appears that hitting and slapping, and not spanking, is driving our results. This may be a result of decreased use of spanking as children age.

Table 4.

Predictors of Mother Reporting Less Corporal Punishment than Child: Odds Ratios from Logistic Regression

| Mother reports less corporal punishment than child | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 1.084 | |

| Hispanic | 1.154 | |

| Immigrant | 0.754 | |

| Education | ||

| Less than HS | 1.008 | |

| Some College | 0.960 | |

| College or more | 1.718* | |

| Poverty (FPL) | ||

| ’0–40% | 0.783 | |

| 50–100% | 0.941 | |

| 100–199% | 1.322 | |

| Marital Status (9-Year) | ||

| Cohabiting | 0.751 | |

| Single | 1.044 | |

| Mother characteristics | ||

| Mother age | 0.989 | |

| First birth | 1.056 | |

| Ever depressed | 0.992 | |

| Parenting stress | 1.071** | |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Child age | 0.979 | |

| Low birth weight | 0.974 | |

| Child male | 0.959 | |

| Externalizing behaviors | 1.041*** | |

| Teacher report of Problem behaviors | 1.004 | |

| Risk factors | ||

| Violent neighborhood | 1.155 | |

| Mother uses drugs | 1.059 | |

| Mother alc. | 0.950 | |

| Mother employed | 1.113 | |

|

| ||

| N | 1,180 | |

Notes

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Includes city fixed effects

Contributor Information

William Schneider, Columbia University, School of Social Work.

Michael MacKenzie, Columbia University, School of Social Work.

Jane Waldfogel, Columbia University, School of Social Work.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Teacher’s College and College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University.

References

- Belsky J. Etiology of Child Maltreatment: A Developmental-Ecological Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 11. 1993;4(3):413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgers N, Hox J, Sikkel D. Response Quality in Survey Research with Children and Adolescents: the effect of labelled response options and vague quantifiers. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2003;15(1):83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Borgers N, Sikkel D, Hox J. Response Effects in Surveys on Children and Adolescents: The Effect of Number of Response Options, Negative Wording, and Neutral Mid-Point. Quality and Quantity. 2004;38(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brayden RM, Altemeier WA, Tucker DD, Dietrich MS, Vietze P. Antecedents of Child Neglect in the First Two Years of Life. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1992;120(3):426–429. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80912-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Schneider W, Waldfogel J. The Great Recession and Risk for Child Maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(10):721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL. Comparison of Parent and Child Reports on Child Maltreatment in a Representative Household Sample in Hong Kong. Journal of Family Violence. 2012;27:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s10896-011-9405-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conron KJ, Beardslee W, Koenen KC, Buka SL, Gortmaker SL. A Longitudinal Study of Maternal Depression and Child Maltreatment in a National Sample of Families Investigated by Child Protective Services. JAMA Pediatrics. 2009;163(10) doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Lee SM, Jonson-Reid M. Race and Child Maltreatment Reporting: Are Blacks Overrepresented? Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(3):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Zuravin S. Bias in Child Maltreatment Reporting: Revisiting the Myth of Classlessness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(2):295– 304. doi: 10.1037/h0080338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Kim J, Black MM, Weisbart C, Semiatin J, Magder LS. Identifying Children at High Risk for a Child Maltreatment Report. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35(2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M. Children and Adolescents as Respondents, Experiments on Question Order, Response Order, Scale effects and the Effect of Numeric Values Associated with Response Options. Journal of Official Statistics. 2005;21(4):701–725. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal Punishment by Parents and Associated Child Behaviors and Experiences: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(4):539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel Y, Overpeck MD, Jones DH, Scheidt PC, Bijur PE, Trumble AC, Anderson J. The Effect of Recall on Estimating Annual Nonfatal Injury Rates for Children and Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:599–605. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Jones B, Stieglitz E, Vitulano L, Mannarino AP. The Use of Multiple Informants to Assess Children’s Maltreatment Experiences. Journal of Family Violence. 1994;9(3):228–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko DJ, Kazdin AE, Day BT. Children’s Perspectives in the Assessment of Family Violence: Psychometric Characteristics and Comparison to Parent Reports. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1(2):156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BJ, George RM. Poverty, Early Childbearing, and Child Maltreatment: A Multinomial Analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 1999;21(9–10):755–780. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Lansford JE, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Parental Agreement of Reporting Parent to Child Aggression Using the Conflict Tactcs Scales. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Kotch JB, Lee LC. Toward a cumulative ecological risk model for the etiology of child maltreatment. Children & Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1638–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Kotch JB, Lee LC, Augsberger A, Hutto N. The cumulative ecological risk model of child maltreatment and child behavioral outcomes: Reconceptualizing reported maltreatment as risk factor. Children & Youth Services Review. 2011;33:2392–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi LK, Gershoff ET, Aber JL. Item-Level Discordance in Parent and Adolescent Reports of Parenting Behavior and Its Implications for Adolescents’ Mental Health and Relationships with Their Parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1035–1052. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9741-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel M, Shook KS. Major Life Events and the Risk of a Child Maltreatment Investigation. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27(2):171–195. [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Wolfe DA, Yuen SA, Wilson SK, Carnochan J. The Measurement of Maltreatment: A Comparison of Approaches. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(2):233–249. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00119-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Parental Resources and Child Abuse and Neglect. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings. 1999;89(2):239– 244. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE, Howell DC. Perspectives on Child Behavior Problems: Comparisons of Children’s Self-reports with Parent and Teacher Reports. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;1(1):68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman N, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile Families: Sample and Design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4/5):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Kollmar F. Discrepancies between Mothers’ and Fathers’ Perceptions of Sons’ and Daughters’ Problem Behaviour: A Longitudinal Analysis of Parent-Adolescent Agreement on Internalising and Externalising Problem Behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1998;39(5):6870697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Huston L, Egeland B. Identification of Child Maltreatment Using Prospective and Self-Report Methodologies: A Comparison of Maltreatment Incidence and Relation to Later Psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel M, Yoo J, Bolger K. Understanding the Risks of Child Neglect: An Exploration of Poverty and Parenting Characteristics. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(4):395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Platt L. Center for Longitudinal Studies. 2013. How do Children Answer Questions About Frequencies and Quantities? Evidence from a Large-scale Field Test. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyon D. Identification of Child Maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and Psychometric Data for a National Sample of American Parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Conflict tactics scales. In: Jackson NA, editor. Domestic violence. New York: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group; 2007. pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima EA, Herrenkohl TI, Huang B, Whitney SD. Measuring Child Maltreatment: A Comparison of Prospective Parent Reports and Retrospective Adolescent Reports. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(4):424–435. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, der Ende VJ. Agreement Between Parents’ and Adolescents’ Self-Reports of Problem Behavior. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1992;33(6):1011–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. Prevention and the Children Protection System. The Future of Children. 2009;19(2):195–210. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The Prevalence of Confirmed Maltreatment Among US Children, 2004–2011. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014:410. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]