Abstract

Objective

To investigate differences in severe maternal morbidity between Hispanics and three major Hispanic subgroups compared with non-Hispanic white mothers and the extent to which differences in delivery hospital may contribute to excess morbidity among Hispanics.

Methods

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study using linked 2011–2013 New York City discharge and birth certificate datasets (n=353,773). Rates of severe maternal morbidity were calculated using a published algorithm based on diagnosis and procedure codes. Mixed effects logistic regression with a random hospital-specific intercept was used to generate risk-standardized severe maternal morbidity rates for each hospital, taking into consideration patient sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities. Differences in the distribution of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white deliveries were assessed among these hospitals in relation to their risk-adjusted morbidity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted after excluding isolated blood transfusion from the morbidity composite.

Results

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 4541 deliveries (2.1%) and was higher among Hispanic than non-Hispanic white women (2.7% vs. 1.5%, p<.001); this rate was 2.9% among those who were Puerto Rican, 2.7% among those who were foreign-born Dominican, and 3.3% among those who were foreign-born Mexican. After adjustment for patient characteristics, the risk remained elevated for Hispanic women (odds ratio =1.42 95% CI 1.22–1.66) and for all three subgroups vs. non-Hispanic white women (p<.001). Risk for Hispanic women was attenuated in sensitivity analyses (odds ratio=1.17 95% CI 1.02–1.33). Risk-standardized morbidity across hospitals varied sixfold. We estimate that Hispanic – non-Hispanic white differences in delivery location may contribute up to 37% of the ethnic disparity in severe maternal morbidity rates in New York City hospitals.

Conclusion

Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white mothers are more likely to deliver at hospitals with higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates and these differences in site of delivery may contribute to excess morbidity among Hispanic mothers. Our results suggest improving quality at the lowest performing hospitals could benefit both non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women and reduce ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity rates.

Introduction

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality exist, though the reasons for these gaps are not fully understood.1,2 Growing attention has focused on location of care as a partial explanation for these disparities.3 In our recent work, we found that non-Hispanic blacks deliver at higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity hospitals.4 Hispanic women in New York City are three times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to suffer pregnancy-related mortality yet few studies have examined how site of care might contribute to these disparities.1 Further, few studies have investigated how maternal risk varies among Hispanic subgroups and the interplay of this risk with site of delivery. Our objective was to examine differences in severe maternal morbidity between Hispanic women and three major Hispanic subgroups versus non-Hispanic white women, and to examine whether these differences are explained by delivery hospital.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study using Vital Statistics birth records linked with New York State discharge abstract data - The Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) for all delivery hospitalizations in New York City from 2011–2013. Data linkage was conducted by the New York State Department of Health and Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the New York State Department of Health, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Delivery hospitalizations were identified based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes and DRG delivery codes.5 Over ninety-eight percent of maternal discharges were linked with infant birth certificates. The final sample included 353,773 total deliveries of live infants at 40 hospitals.

Hispanic ethnic ancestry was obtained by self-report from the birth certificate. We were able in our dataset to identify three Hispanic subgroups based on the Hispanic categories included in the question on the New York City birth certificate – foreign-born Dominican, foreign-born Mexican, and Puerto Rican. Race was obtained by self-report from the birth certificate. Maternal race and Hispanic ethnicity in birth certificate data have been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity.6 This article compares severe maternal morbidity among Hispanics of any racial group versus non-Hispanic white mothers in New York City.

We used a published algorithm to identify severe maternal morbidity, using diagnoses for life-threatening conditions and procedure codes for life-saving procedures defined by investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)7,8 (see Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). We risk-adjusted hospital-level rates of maternal morbidity using mothers’ sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., self-identified race and ethnicity, age, country of birth), and clinical and obstetric factors (e.g., multiple pregnancy, history of previous cesarean delivery, body mass index, prenatal care). Similar to others we also adjusted for clinical comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, premature rupture of membranes, disorders of placentation).9–12

Teaching status was obtained from the American Hospital Association, ownership and nursery level from the New York State Department of Health, and volume of deliveries in each hospital from SPARCS.

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and clinical conditions of Hispanics overall and for the three major subgroups with non-Hispanic white women using Chi Square tests. As our focus was to examine the three most prevalent Hispanic subgroups in New York City, we did not conduct subgroup analyses on the remaining group of other Hispanics (n=41,091). This group was comprised of foreign born and US-born Hispanic women from Caribbean, Central and South American countries. We then compared severe maternal morbidity rates across these groups using logistic regression to adjust for the differences in maternal sociodemographic and clinical covariates and also, in a second model, for hospital fixed-effects. Robust standard errors were used to account for clustering in hospitals.

To evaluate variability between hospitals, we used mixed-effects logistic regression with the same patient characteristics and a random hospital-specific intercept to generate risk-standardized severe maternal morbidity rates (SSMMR) for each hospital using methods recommended by CMS compare.12,13 These analyses included women of all racial and ethnic groups who delivered in New York City.12,13 These rates were the ratio of predicted to expected severe maternal morbidity rates, multiplied by the New York City average severe maternal morbidity rate.12 For each hospital, the numerator of the ratio is the number of severe maternal morbidity cases predicted on the bases of the hospital’s performance with its case-mix, and the denominator is the number of severe maternal morbidity cases expected on the bases of the New York City performance with that hospital’s case mix. These models employ empirical Bayesian methods that “shrink” estimates from small hospitals, which tend to be outliers in statistical models, toward the mean hospital outcome.14 We ranked hospitals from lowest to highest risk-standardized severe maternal morbidity rates. These analyses did not include hospital-level variables,12 because doing so could distort the ranking of hospitals. Because blood transfusions account for a significant proportion of severe maternal morbidity events, we conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, given that isolated blood transfusions do not include information on number of units transfused and therefore may not be reflective of severe events, we examined whether isolated blood transfusions in this cohort were associated with excess risk (e.g. placentation disorders, hypertension, and other comorbidities) using a multivariable logistic model. Second, we examined the correlation between hospital rankings based on risk-standardized severe maternal morbidity with and without blood transfusion. Third, we examined risk of severe maternal morbidity without blood transfusion for Hispanic and white women and confirmed that Hispanic women had an elevated risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rate when isolated blood transfusions were removed from the index after taking into consideration patient and clinical comorbidities.

To assess ethnic disparities in the use of hospitals with the lowest morbidity rates, we calculated the cumulative distributions of births among hospitals ranked from the lowest to the highest standardized morbidity rate for Hispanic mothers overall and for the three major ethnic groups versus white mothers. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess whether the distributions of deliveries among hospitals differed for white and Hispanic women.15 We also compared the distribution of Hispanic mothers overall and for the three major ethnic groups versus non-Hispanic white deliveries in the lowest morbidity tertile of hospitals using Chi Square tests.

These statistical analyses assess whether Hispanic mothers are systematically receiving care at lower-quality hospitals but do not provide a measure of the magnitude of the consequences for Hispanic mothers’ health of receiving lower quality care. To address the magnitude, we conducted a simulation and asked what would happen if Hispanic women went to the same hospitals as non-Hispanic white women. This methodology has been previously described.4,16 We used the same risk-standardized morbidity model and kept all individual patient characteristics the same. We calculated the predicted probability of morbidity for each Hispanic mother at each hospital. For each Hispanic mother, we took the weighted average of these probabilities, where weights were the percentage of non-Hispanic white mothers who went to each hospital. The difference between the predicted probability at the hospital a Hispanic mother went to and the weighted average probability if the Hispanic mother delivered at the non-Hispanic white mother’s hospital is the decrease or increase in the probability of a morbid event. The sum of the difference in probabilities across all Hispanic women is the morbid events avoided if Hispanic mothers went to the same hospitals as white mothers.4,16 We conducted similar simulations for mothers in the three Hispanic subgroups, such that each foreign-born Dominican, foreign-born Mexican, and Puerto Rican mother, went to the same hospitals as non-Hispanic white women.

Next we examined the potential impact on disparities between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white morbidity rates of improving quality in low performing hospitals. We estimated the effect of lowering severe maternal morbidity rates in the highest morbidity tertile of hospitals to the average of the remaining hospitals. We did this by estimating a logistic model with maternal characteristics and a single dummy variable for whether the delivery hospital was in the highest morbidity tertile, setting this dummy variable equal to 0 for all mothers, and calculating the predicted morbid events. We also estimated the effect of a reduction in severe maternal morbidity rates of the middle and highest morbidity tertiles of hospitals to the average of the remaining hospitals using similar methods.

All statistical analysis was performed using the SAS system software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Hispanic mothers accounted for 29.9% and white mothers for 31.1% of the 353,773 deliveries in New York City in 2011–2013. Hispanic women were more likely to be younger, born outside of the US, obese, have Medicaid insurance, and more likely to suffer from a number of comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (Table 1).

Table I.

Socio-demographic, Clinical and Hospital Characteristics of Deliveries for Hispanics and non-Hispanic White Women in New York City Hospitals

| Hispanic | White | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Deliveries | 105926 | 100.0 | 110200 | 100.0 | |

| Maternal Age in years | <.001 | ||||

| <20 | 9619 | 9.1 | 1341 | 1.2 | |

| 20–29 | 54969 | 51.9 | 37812 | 34.3 | |

| 30–34 | 24439 | 23.1 | 38161 | 34.6 | |

| 35–39 | 13231 | 12.5 | 25135 | 22.8 | |

| 40–44 | 3477 | 3.3 | 7079 | 6.4 | |

| 45+ | 191 | 0.2 | 672 | 0.6 | |

| Ancestry | <.001 | ||||

| US Born | 48162 | 45.5 | 79935 | 72.5 | |

| Foreign Born | 57764 | 54.5 | 30265 | 27.5 | |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index(kg/m2) | <.001 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 3353 | 3.2 | 6549 | 5.9 | |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 47665 | 45.0 | 73017 | 66.2 | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 31442 | 29.7 | 20234 | 18.4 | |

| Obese (30.0–39.9) | 19810 | 18.7 | 9006 | 8.2 | |

| Morbid Obesity (≥40) | 2737 | 2.6 | 1120 | 1.0 | |

| Missing BMI | 919 | 0.9 | 274 | 0.3 | |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 2728 | 2.6 | 2573 | 2.3 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 1287 | 1.2 | 1220 | 1.1 | <.001 |

| Illegal drugs use during pregnancy | 460 | 0.4 | 182 | 0.2 | <.001 |

| Maternal Education | <.001 | ||||

| Less than high school | 38722 | 36.6 | 8726 | 7.9 | |

| High school | 25367 | 24.0 | 20612 | 18.7 | |

| Greater than high school | 41600 | 39.3 | 80620 | 73.2 | |

| Missing or unknown | 237 | 0.2 | 242 | 0.2 | |

| Insurance | <.001 | ||||

| Commercial | 19890 | 18.8 | 70105 | 63.2 | |

| Medicaid | 84566 | 79.3 | 38532 | 35.0 | |

| Other | 500 | 0.5 | 815 | 0.7 | |

| Uninsured | 969 | 0.9 | 748 | 0.7 | |

| Prenatal visits | <.001 | ||||

| 0–5 | 7776 | 7.3 | 3737 | 3.4 | |

| 6–8 | 13697 | 12.9 | 11052 | 10.0 | |

| ≥9 | 83459 | 78.8 | 94833 | 86.1 | |

| Unknown | 994 | 0.9 | 578 | 0.5 | |

| Parity | <.001 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 62444 | 59.0 | 58308 | 52.9 | |

| Multiparous | 43327 | 40.9 | 51746 | 46.7 | |

| Missing | 155 | 0.2 | 146 | 0.1 | |

| Type of Pregnancy | <.001 | ||||

| Singleton | 104475 | 98.6 | 107165 | 97.3 | |

| Multiple | 1451 | 1.4 | 3035 | 2.8 | |

| Previous Cesarean | 19479 | 18.4 | 15959 | 14.5 | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Cardiac Disease | 316 | 0.3 | 616 | 0.6 | <.001 |

| Renal Disease | 78 | 0.1 | 49 | 0.0 | <.001 |

| Musculoskeletal Disease | 352 | 0.3 | 341 | 0.3 | <.001 |

| Digestive Disorder | 29 | 0.0 | 269 | 0.2 | <.001 |

| Blood Disease | 12288 | 11.6 | 9013 | 8.2 | <.001 |

| Mental Disorders | 3669 | 3.5 | 3364 | 3.1 | <.001 |

| CNS disease | 1323 | 1.3 | 1310 | 1.2 | <.001 |

| Rheumatic Heart Disease | 57 | 0.05 | 33 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Disorder Placentation | 1636 | 1.54 | 1599 | 1.45 | <.001 |

| Chronic Hypertension | 1345 | 1.3 | 807 | 0.7 | <.001 |

| Pregnancy Hypertension | 7623 | 7.2 | 4411 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Lupus | 224 | 0.2 | 117 | 0.1 | <.001 |

| Collagen Vascular Disorder | 34 | 0.03 | 72 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 106 | 0.10 | 149 | 0.14 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1278 | 1.2 | 585 | 0.5 | <.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 6400 | 6.0 | 3534 | 3.2 | <.001 |

| Asthma/Chronic bronchitis | 7378 | 7.0 | 3174 | 2.9 | <.001 |

| Delivery method | <.001 | ||||

| Cesarean Delivery | 35161 | 33.2 | 31405 | 28.5 | |

| Vaginal delivery | 70765 | 66.8 | 78795 | 71.5 | |

| Hospital Characteristics1 | |||||

| Hospital Ownership | <.001 | ||||

| Public | 28397 | 26.8 | 3574 | 3.2 | |

| Private | 77529 | 73.2 | 106626 | 96.8 | |

| Teaching Status | <.001 | ||||

| Not Teaching | 2559 | 2.4 | 1200 | 1.1 | |

| Teaching | 103367 | 97.6 | 109000 | 98.9 | |

| Nursery Level | <.001 | ||||

| Level 2 | 17127 | 16.2 | 7219 | 6.6 | |

| Level 3–4 | 88799 | 83.8 | 102981 | 93.5 | |

| Delivery Volume 2 | <.001 | ||||

| Low | 16047 | 15.2 | 3143 | 2.9 | |

| Medium | 29128 | 27.5 | 4203 | 3.8 | |

| High | 31172 | 29.4 | 22954 | 20.8 | |

| Very High | 29579 | 27.9 | 79900 | 72.5 | |

Based on 3 years of data from 2011–2013

Hospital volume for three years combined data:

Volume Designations by Quartile: Low: 2276–4191, Medium: 4489–7130, High: 7148–12400, Very High: 12408–23912 deliveries

Maternal sociodemographic and clinical characteristics also differed significantly among the three Hispanic subgroups (Table 2). Puerto Rican women were younger, and were more likely to have private insurance than those who were foreign-born Mexican or Dominican. Foreign-born Mexican mothers were half as likely as either Puerto Rican or foreign-born Dominican mothers to have a high school education. All three Hispanic subgroups had elevated rates of hypertension and gestational diabetes, and Mexican women had the highest rates of gestational diabetes. Puerto Rican women had higher rates of obesity and asthma than Mexican and Dominican women.

Table II.

Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Deliveries by Hispanic Subgroups in New York City Hospitals

| Puerto Rican | Foreign born Mexican | Foreign born Dominican | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Deliveries | 24431 | 100 | 18065 | 100 | 22338 | 100 | |

| Maternal age in years | |||||||

| <20 | 2905 | 11.9 | 975 | 5.4 | 1451 | 6.5 | <.001 |

| 20–34 | 18274 | 37.1 | 14108 | 78.1 | 16997 | 76.1 | |

| 35–39 | 2523 | 31.8 | 2423 | 13.4 | 2993 | 13.4 | |

| 40–44 | 687 | 2.8 | 534 | 3.0 | 849 | 3.8 | |

| 45+ | 42 | 0.2 | 25 | 0.1 | 48 | 0.2 | |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index(kg/m2) | |||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 904 | 3.7 | 408 | 2.3 | 799 | 3.6 | <.001 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 9557 | 39.1 | 7688 | 42.6 | 11295 | 50.6 | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 6814 | 27.9 | 6151 | 34.1 | 6349 | 28.4 | |

| Obese (30.0–39.9) | 5851 | 24 | 3250 | 18 | 3399 | 15.2 | |

| Morbid Obesity (≥40) | 1192 | 4.9 | 252 | 1.4 | 337 | 1.5 | |

| Missing BMI | 114 | 0.5 | 316 | 1.6 | 159 | 0.7 | |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 1599 | 6.5 | 81 | 0.5 | 228 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 258 | 1.1 | 99 | 0.6 | 213 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Illegal drugs use during pregnancy | 231 | 1.0 | 33 | 0.2 | 62 | 0.3 | <.001 |

| Maternal Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 7644 | 31.3 | 11516 | 63.8 | 6586 | 29.5 | <.001 |

| High school | 6052 | 24.8 | 4879 | 27 | 5421 | 24.3 | |

| Greater than high school | 10714 | 43.9 | 1602 | 8.9 | 10280 | 46.0 | |

| Missing or unknown | 22 | 0.1 | 68 | 0.4 | 51 | 0.2 | |

| Insurance | |||||||

| Commercial | 6141 | 25.1 | 609 | 3.4 | 3155 | 14.1 | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 17830 | 73.0 | 17308 | 95.8 | 18992 | 84.7 | |

| Other | 181 | 0.7 | 14 | 0.1 | 80 | 0.4 | |

| Uninsured | 280 | 1.2 | 143 | 0.7 | 181 | 0.8 | |

| Prenatal visits | |||||||

| 0–5 | 2282 | 9.3 | 933 | 5.2 | 1707 | 7.6 | <.001 |

| 6–8 | 3693 | 15.1 | 1893 | 10.5 | 3047 | 13.6 | |

| ≥9 | 18172 | 74.4 | 15133 | 83.8 | 17370 | 77.8 | |

| Unknown | 285 | 1.2 | 106 | 0.6 | 214 | 1.0 | |

| Parity | |||||||

| Nulliparous | 10666 | 43.7 | 4545 | 25.2 | 9204 | 41.2 | <.001 |

| Multiparous | 13765 | 56.3 | 13520 | 74.8 | 13134 | 58.8 | <.001 |

| Type of Pregnancy | |||||||

| Singleton | 24020 | 98.3 | 17907 | 99.1 | 22009 | 98.5 | <.001 |

| Multiple | 411 | 1.7 | 158 | 0.9 | 329 | 1.5 | <.001 |

| Previous Cesarean | 4118 | 16.9 | 3713 | 20.6 | 5358 | 24.0 | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Cardiac Disease | 107 | 0.4 | 20 | 0.1 | 72 | 0.3 | <.001 |

| Renal Disease | 29 | 0.1 | 14 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.0 | 0.01 |

| Musculoskeletal | 161 | 0.7 | 23 | 0.1 | 40 | 0.2 | <.001 |

| Digestive Disorder | 17 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | <.001 |

| Blood Disease | 2963 | 12.1 | 2179 | 12.1 | 2687 | 12.0 | 0.95 |

| Mental Disorder | 1677 | 6.9 | 181 | 1.0 | 596 | 2.7 | <.001 |

| CNS | 531 | 2.2 | 69 | 0.4 | 271 | 1.2 | <.001 |

| Rheumatic heart | 14 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.1 | 16 | 0.1 | 0.66 |

| Disorder Placentation | 421 | 1.7 | 244 | 1.4 | 329 | 1.5 | .006 |

| Chronic Hypertension | 446 | 1.8 | 78 | 0.4 | 388 | 1.7 | <.001 |

| Pregnancy Hypertension | 1956 | 8.0 | 1258 | 7.0 | 1641 | 7.4 | .0002 |

| Lupus | 101 | 0.4 | 15 | 0.1 | 28 | 0.1 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 368 | 1.5 | 361 | 2.0 | 215 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 1464 | 6.0 | 1786 | 9.9 | 1259 | 5.6 | <.001 |

| Asthma/Chronic bronchitis | 3906 | 16.0 | 183 | 1.0 | 964 | 4.3 | <.001 |

| Delivery method | |||||||

| Cesarean Delivery | 8306 | 34.0 | 4978 | 27.6 | 9130 | 40.9 | <.001 |

| Vaginal delivery | 16126 | 66.0 | 13087 | 72.4 | 13208 | 59.1 | <.001 |

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 4541 deliveries and rates were higher among Hispanic (2.7%) as compared with non-Hispanic white (1.5%) mothers (p<.001, Table 3). Rates of severe maternal morbidity were even higher among the three subgroups of Hispanic women (2.9% among Puerto Rican, 2.7% among foreign-born Dominican, 3.3% among foreign-born Mexican). These differences remained in adjusted models, but odds ratio decreased from 1.87 (95% CI 1.76–1.99) to 1.42 (95%CI 1.22–1.66) for Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white women after accounting for other maternal sociodemographic and clinical factors. Odds ratios were reduced further after accounting for site of delivery (OR =1.26, 95%CI 1.18–1.42). Risks were elevated among the three major Hispanic subgroups, with the highest odds for morbid events among foreign-born Mexican women.

Table III.

Association Between Hispanic Ethnicity and Severe Maternal Morbidity

| Ethnicity | Severe Morbid Events (n) | SMM Rate (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Model 1* [Adjusted OR (95% CI)] | Model 2† [Adjusted OR (95% CI)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,636 | 1.48 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Hispanic | 2,905 | 2.74 | 1.87 (1.76–1.99) | 1.42 (1.22–1.66) | 1.26 (1.18–1.42) |

| Population subgroup | |||||

| Puerto Rican | 706 | 2.89 | 2.25 (2.04–2.47) | 1.85 (1.52–2.25) | 1.71 (1.44–2.03) |

| Foreign Mexican | 592 | 3.28 | 1.87 (1.70–2.05) | 1.40 (1.14–1.72) | 1.21 (1.03–1.42) |

| Foreign Dominican | 611 | 2.74 | 1.98 (1.81–2.16) | 1.56 (1.31–1.85) | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) |

SMM, severe maternal morbidity; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for patient characteristics and clustering of patients within hospitals.

Adjusted for patient characteristics, delivery hospital, and clustering of patients within hospital.

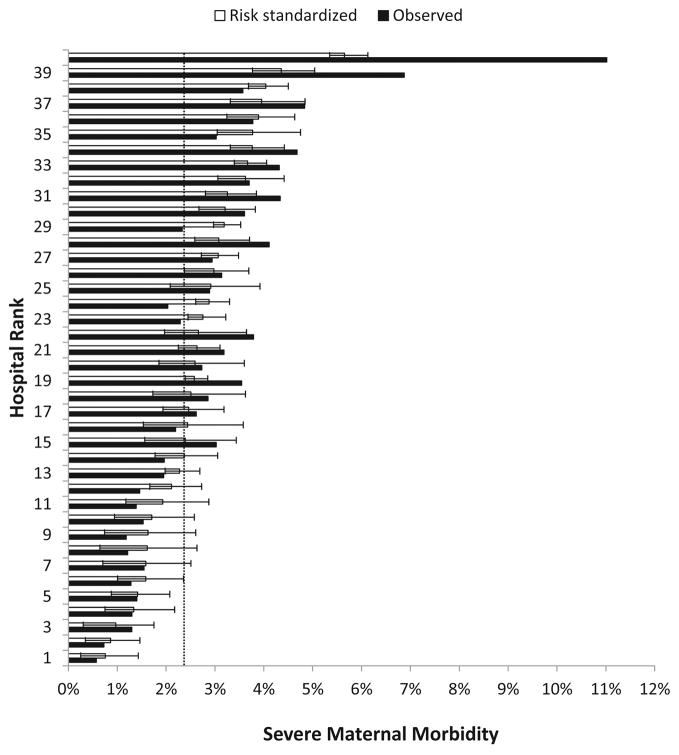

Of the 40 hospitals, 11 were public, 33 had Level III or IV nurseries, and 39 were teaching hospitals. The median percent of Hispanic deliveries was 28.7 (IQR 17.1–54.2%, min 6.8% and max 89.5%). Observed severe morbidity rates for hospitals ranged from 0.6% to 11.5% and risk standardized rates using a model including maternal sociodemographic and clinical characteristics) from 0.8% to 5.7% (Figure 1). The risk-standardized morbidity rate for the highest mortality tertile of hospitals was 3.8% and 1.5% for the lowest (p<0.001). Isolated blood transfusions accounted for 67% of severe morbid events. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that isolated blood transfusions were a marker of excess risk and were strongly associated with placentation disorders, hypertension, pregnancy induced hypertension, previous cesarean delivery and a number of other comorbidities. In addition, sensitivity analyses demonstrated that hospital rankings based on the CDC severe maternal morbidity algorithm with and without blood transfusion were highly correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.67, p<0.001) and confirmed that Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white women had an elevated but attenuated risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rate when isolated blood transfusions were removed from the index (OR=1.17 95% CI 1.02–1.33).

Figure 1.

Observed and risk SSMMRs in New York City hospitals. Dotted line shows New York City mean observed severe maternal morbidity. The 95% confidence interval for risk SSMMR is shown. SSMMR, standardized severe maternal morbidity rate. Reprinted from American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 215(2), Elizabeth A. Howell, Natalia N. Egorova, Amy Balbierz, Jennifer Zeitlin, Paul L. Hebert, Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity, 143–52, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

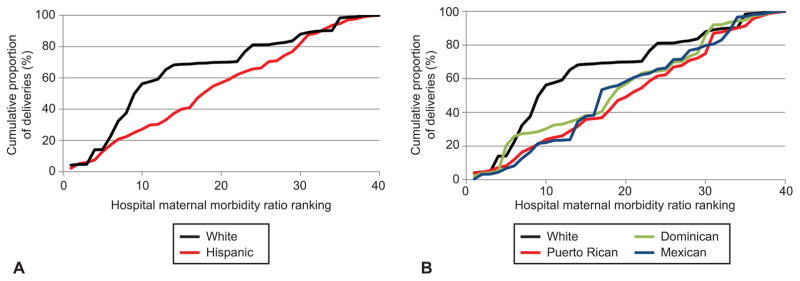

The cumulative distribution of deliveries among hospitals ranked from lowest to highest morbidity rates differed for Hispanic and non-Hispanic white mothers (p=0.003, Figure 2). The majority of non-Hispanic white deliveries (65.3%) occurred in the hospitals in the lowest tertile for severe morbidity compared with 33.0% of all Hispanic deliveries; 29.0% Puerto Rican, 34.4% Dominican, and 23.8% of Mexican women delivered in those same hospitals.

Figure 2.

Cumulative distributions of deliveries according to hospital, ranked from lowest (1) to highest (40) morbidity ratio. A. Hispanic and Non-Hispanic white mothers. B. Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Non-Hispanic white mothers.

If Hispanic mothers delivered in the same hospitals as non-Hispanic white women, our simulation model estimated that they would experience 485 fewer severe morbid events, leading to a reduction of the Hispanic severe maternal morbidity rate from 2.74% to 2.28%, removing 36.5% of the Hispanic-white disparity in severe maternal morbidity (Table 4). By ethnic subgroup, Puerto Rican women would experience 131 fewer severe morbid events, foreign Mexican women would experience 93 fewer events, and foreign Dominican women would experience 114 fewer events.

Table IV.

Effects of Ethnic Differences in Distribution of Deliveries on Severe Maternal Morbidity and Impact of Improving Quality at Low Performing Hospitals on Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity Rates

| Observed | If Hispanic Women delivered at each hospital in same proportion as White Women | If lowest-performing hospitals achieved average SMM rates of remaining hospitals | If lowest and mid performing hospitals achieved average SMM rates of top tertile hospitals | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| SMM rate (%) | Hispanic-White disparity (%) | SMM rate (%) | Morbid events avoided | Reduction in disparity (%) | SMM rate (%) | Morbid events avoided | Reduction in disparity (%) | SMM rate (%) | Morbid events avoided | Reduction in disparity (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 1.48 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.35 | 145 | -- | 1.08 | 446 | -- |

| Hispanic | 2.74 | 1.26 | 2.28 | 485 | 37% | 2.45 | 306 | 13% | 1.66 | 1139 | 54% |

| Population sub-groups | |||||||||||

| Foreign Mexican | 3.28 | 1.8 | 2.76 | 93 | 29% | 2.94 | 60 | 12% | 1.96 | 236 | 51% |

| Foreign Dominican | 2.74 | 1.26 | 2.22 | 114 | 41% | 2.46 | 60 | 12% | 1.66 | 239 | 54% |

| Puerto Rican | 2.89 | 1.41 | 2.35 | 131 | 38% | 2.62 | 85 | 10% | 1.68 | 293 | 57% |

If quality of care were improved in New York City hospitals such that morbidity in the worse performing hospitals was reduced to the average of other New York City hospitals, 306 Hispanic and 145 non-Hispanic white severe morbid events could be averted and the Hispanic-white disparity would be narrowed by 13%. If the severe maternal morbidity rates of the middle and highest morbidity tertiles of hospitals were reduced to the average of the remaining hospitals, 1139 Hispanic and 446 non-Hispanic white morbid events could be avoided and the Hispanic-white disparity would be narrowed by 54%.

Discussion

Hispanic women in New York City deliver in higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity hospitals than non-Hispanic white women, and these differences in site of care may contribute to Hispanic–non-Hispanic white disparities. All three ethnic subgroups, Puerto Rican, foreign-born Mexican, and foreign-born Dominican, had elevated rates of severe maternal morbidity and delivered in higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity hospitals than non-Hispanic white women. Our findings suggest that site of delivery matters and that differences in quality of care may contribute to Hispanic- non-Hispanic white disparities. Our results raise the hypothesis that quality improvement efforts at high maternal morbidity hospitals could result in reductions in maternal morbidity overall and in Hispanic-white disparities. Our results also document the excess comorbidities of Hispanic women.

Our findings are consistent with previous literature demonstrating black–white disparities in severe maternal morbidity in New York City and the United States.3,4 Minorities deliver in a concentrated set of hospitals and these hospitals have higher rates of severe maternal morbidity and lower quality. Similar findings have been documented in other clinical areas.17,18 Given that over one-third of maternal deaths and severe morbid events are considered preventable,19 there have been major efforts by the AmericanCollege of Obstetricians and Gynecologists District II, Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health (AIM Program), Merck for Mothers, and the New York State Department of Health to standardize care on labor and delivery units and enhance quality.20–24 Our data highlight the need for these quality improvement efforts as wide variation in risk-adjusted morbidity rates exists across hospitals. Research studies investigating organizational, structural, and process-related hospital characteristics as well as physician practice patterns that are associated with high performance in maternity care are needed.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies documenting significant racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity even after adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical factors and suggest that specifically targeted quality improvement efforts to reduce disparities in maternal outcomes are needed. One such effort under development is the Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health Reduction of Peripartum Racial/Ethnic Disparities Patient Safety Bundle, which aims to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality across the United States.24 Data from other areas of medicine suggest that multi-factorial tailored interventions can reduce disparities and improve health outcomes.25

Our data highlight a paradox: While perinatal outcomes are often better among Hispanic women, our results as well as data from others suggest that rates of adverse maternal outcomes are often higher among these women.26 Foreign-born Mexican women in New York City have infant mortality rates that are lower than non-Hispanic white women, yet our data demonstrate that foreign-born Mexican women have the highest adjusted risks of severe maternal morbidity.27 Our findings suggest that the balance of relative disadvantage and advantage experienced by Hispanic women that results in a lower risk of adverse birth outcomes may be different for maternal health outcomes, such that the balance is tipped toward disadvantage. Our data also demonstrate the importance of examining subgroups of Hispanics to better understand risk and protective factors.

Our analysis has limitations. For assessment of severe maternal morbidity we used administrative data (ICD-9 procedure and diagnosis codes) that do not contain important clinical data on severity of illness and the composite measure we utilized relies heavily on blood transfusions. Nevertheless the published algorithm we used to identify severe maternal morbidity has been validated and our sensitivity analyses after removing isolated blood transfusions confirmed our findings.28 Risk for Hispanic women was attenuated when isolated blood transfusions were removed from the morbidity composite. Birth certificate has only moderate reliability for behavioral risk factors and medical events.29 We used a simulation model and estimated the extent to which differences in the distribution of deliveries may contribute to disparities but were unable to account for unmeasured factors that are associated with both ethnicity and severe maternal morbidity. The strengths are that we conducted a population-based study and were able to construct a robust risk-adjustment model that included important confounders available in our linked data set (e.g. education, body mass index).

New York City has elevated rates of morbidity and mortality among Hispanic women. Given that Hispanics account for over a third of all births in New York City and are the fastest growing minority in the country, research investigating the clinical characteristics and patterns of care among Hispanic women is an important step towards targeting interventions to reduce these disparities. New York City and the nation are becoming increasingly diverse and our findings demonstrate that many ethnic women deliver their babies in institutions with worse outcomes. Policymakers need to understand the challenges of delivering high-quality obstetrical care at these hospitals and find ways to improve it.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD007651)

Footnotes

Presented at Academy Health Annual Research Meeting June 26, 2016, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of Maternal IaRH. Pregnancy-Associated Mortality New York City, 2006–2010. New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;125(6):1460–1467. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214(1):122e121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 May 12; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J. 2008 Jul;12(4):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister L, Marchi K, Pearl M, Williams R, Braveman P. The validity of information on “race” and “Hispanic ethnicity” in California birth certificate data. Health Serv Res. 2000 Oct;35(4):869–883. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 29, 2014];Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/SevereMaternalMorbidity.html.

- 9.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Nov;26(6):506–514. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivas SK, Fager C, Lorch SA. Evaluating risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rate as a measure of obstetric quality. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;115(5):1007–1013. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d9f4b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grobman WA, Feinglass J, Murthy S. Are the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality obstetric trauma indicators valid measures of hospital safety? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;195(3):868–874. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz A, Egorova N. Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA. 2014 Oct 15;312(15):1531–1541. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ash AS, Normand ST, Stukel TA, Utts J Committee of Presidents of Statistical Societies (COPSS) Statistical Issues in Assessing Hospital Performance. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Yale NewHaven Health Services Corporation, Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimick JB, Staiger DO, Birkmeyer JD. Ranking hospitals on surgical mortality: the importance of reliability adjustment. Health Serv Res. 2010 Dec;45(6 Pt 1):1614–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollander M, Wolfe DA. Nonparametric Statistical Methods. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert PL, Howell EA, Wong ES, et al. Methods for Measuring Racial Differences in Hospitals Outcomes Attributable to Disparities in Use of High-Quality Hospital Care. Health Serv Res. 2016 Jun 3; doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005 Apr;43(4):308–319. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008 Mar;121(3):e407–415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014 Jan;23(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kacica MA. Maternal Mortality Review. New York State Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACOG SMIB. 2015 http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Districts/District-II/Safe-Motherhood-Initiative-bundles.

- 22.Arora KS, Shields LE, Grobman WA, D’Alton ME, Lappen JR, Mercer BM. Triggers, Bundles, Protocols, and Checklists - What Every Maternal Care Provider Needs to Know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct 15; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mothers Mf. [Accessed 11/5/15];2015 http://www.merckformothers.com/our-work/united-states.html.

- 24.Health AfIoM. [Accessed June 26, 2016];2015 http://www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim.php.

- 25.Peek ME, Ferguson M, Bergeron N, Maltby D, Chin MH. Integrated community-healthcare diabetes interventions to reduce disparities. Curr Diab Rep. 2014 Mar;14(3):467. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins FW, MacKay AP, Koonin LM, Berg CJ, Irwin M, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality in Hispanic women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Nov;94(5 Pt 1):747–752. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Huynh M, Lee E, et al. Summary of Vital Statistics, 2014. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Office of Vital Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Main EK, Abreo A, McNulty J, et al. Measuring severe maternal morbidity: validation of potential measures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 May;214(5):643e641–643 e610. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinikoor LC, Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS. Reliability of variables on the North Carolina birth certificate: a comparison with directly queried values from a cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010 Jan;24(1):102–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.