Abstract

Purpose

This paper describes the implementation of an innovative program that aims to improve postpartum care through a set of coordinated delivery and payment system changes designed to use postpartum care as an opportunity to impact the current and future health of vulnerable women and reduce disparities in health outcomes among minority women.

Description

A large health care system, a Medicaid managed care organization, and a multidisciplinary team of experts in obstetrics, health economics, and health disparities designed an intervention to improve postpartum care for women identified as high-risk. The program includes a social work/care management component and a payment system redesign with a cost-sharing arrangement between the health system and the Medicaid managed care plan to cover the cost of staff, clinician education, performance feedback, and clinic/clinician financial incentives. The goal is to enroll 510 high-risk postpartum mothers.

Assessment

The primary outcome of interest is a timely postpartum visit in accordance with NCQA HEDIS guidelines. Secondary outcomes include care process measures for women with specific high-risk conditions, emergency room visits, postpartum readmissions, depression screens, and health care costs.

Conclusion

Our evidence-based program focuses on an important area of maternal health, targets racial/ethnic disparities in postpartum care, utilizes an innovative payment reform strategy, and brings together insurers, researchers, clinicians, and policy experts to work together to foster health and wellness for postpartum women and reduce disparities

Keywords: maternal health, payment reform, disparities, Medicaid

I. Introduction

Childbirth is the number one reason for hospital admission,1 and postpartum care offers a crucial opportunity to impact the current and future health of vulnerable women. Compared with non-Hispanic white women, black and Hispanic women experience greater maternal mortality, life-threatening morbidities and pregnancy complications, as well as a higher risk of chronic illness such as hypertension and diabetes.2–4 These conditions are also a leading cause of postpartum hospital readmissions and women from ethnic and racial minority groups are less likely to get appropriate follow-up postpartum care, placing not only their current but also long-term health at risk.5

The high US maternal mortality rates and the significant and persistent ethnic and racial disparities in outcomes have heightened focus on improving the health of women during the preconception and interconception periods. There is also a growing recognition of the importance of postpartum care both for monitoring the health of women with chronic illness and as a means to connect vulnerable women with the health care system. However, successfully addressing the pressing need to improve postpartum care for women in vulnerable populations requires not only changes to the delivery aspects of care, but also an active engagement and commitment from the multiple stakeholders integral to the decision-making process for payment and delivery of care.

For this project, a large healthcare system, a Medicaid managed care organization, and a multidisciplinary team of experts in obstetrics, health disparities, and health economics designed an intervention to improve postpartum care for high-risk women. The focus of this intervention is on improving a set of specific metrics that compose the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) postpartum guidelines. Given that disparities in these metrics arise from a complex host of payment and system-wide processes, our project combines a social work-case management intervention and a new payment system designed to align incentives and expand the resources available to clinicians and patients.

II. Preliminary Evidence and Program Description

The postpartum visit is crucial to monitor the health of postpartum women, promote breastfeeding, and is especially important for women with gestational diabetes who require glucose screening. Preliminary data from the health system where the intervention is being implemented and from the Medicaid managed care health insurance plan suggest that the postpartum visit rate is approximately 58% for this population and that fewer than a third of women with gestational diabetes return for their postpartum visit and complete the appropriate fasting glucose screen. National estimates for postpartum visits among commercially insured are above 80%.6 Multiple barriers exist including transportation, child care demands, and poor clinician-patient communication. Preliminary data also suggest that hypertension is a leading diagnosis associated with postpartum readmissions. Our preliminary data demonstrated significant disparities in the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among women delivering at our hospital and striking disparities in the receipt of postpartum care.

Our program attempts to improve postpartum care through a set of coordinated postpartum delivery and payment system changes that build on the evidence base. First, the delivery system redesign is based on a social work/care coordinator-based case management intervention that combines components from two interventions designed to decrease hospital readmissions among chronically ill patients and reduce postpartum depression.7,8 Second, the payment system redesign aims to incorporate aspects of the evidence base from behavioral economics on financial and nonfinancial incentives to support care coordination. Through a cost-sharing arrangement between the health system and the main insurer of our project’s targeted sample (a large Medicaid managed care plan) we were able to defray expenses related to employing a social worker and a care coordinator, clinician education related to postpartum care, and clinician/clinic-level feedback on postpartum care performance. This increased access to much needed resources and education for practitioners in this setting acts as an incentive and enables higher quality of delivery of care. Clinician/clinic-level financial incentives in the form of enhanced payments for completed postpartum visits by the payer were rolled out in the 12th month of through the intervention.

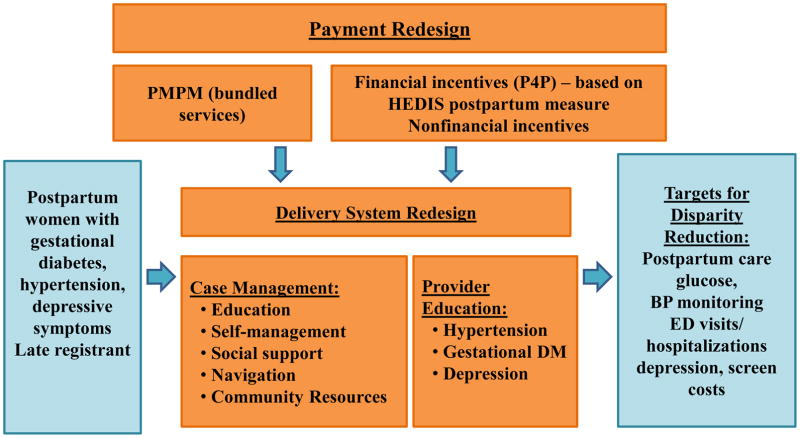

Figure 1 summarizes the different elements of the delivery and payment system redesign. The program focuses on women at high risk of adverse health outcomes that would benefit from having a timely postpartum care visit (i.e., women with gestational diabetes, hypertension, depressive symptoms, and late registrants for prenatal care). We believe that the combination of delivery system and payment redesign is critical to program effectiveness because it allows high risk women to access resources promptly and as needed while also providing financial and nonfinancial incentives to all stakeholders to improve care coordination and eliminate bottlenecks in the health care delivery system.

Fig. 1.

Delivery and payment redesign: elements

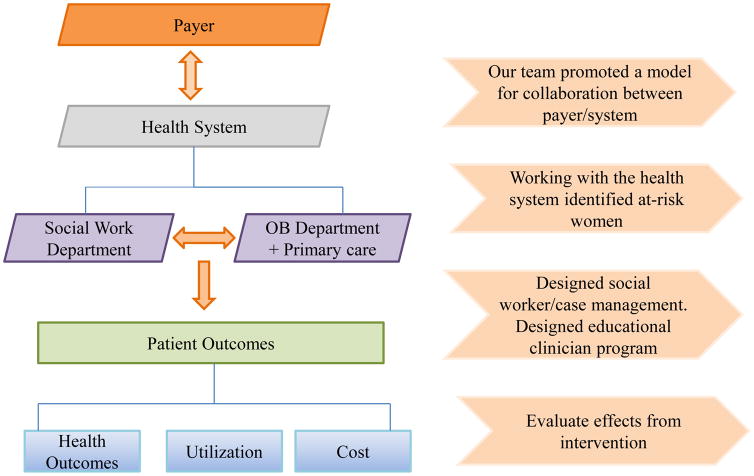

Figure 2 presents a conceptual model of the overall delivery and payment system redesign. Developing a framework for discussions between a health system and payer is fundamental to get the redesign process started, promote trust, and foster collaboration among partners. One key element is for all participants to have a clear understanding of the different incentives and constraints faced by the different organizations they represent. In our case, some of our team members had expertise in health economics and payment systems that facilitated the communication between the health system and the payer and, thus, complemented the expertise available at these organizations and even served as a neutral third party to the discussions on delivery system and payment redesign.

Fig. 2.

Delivery and payment redesign: conceptual model

The main goal of our multi-layered intervention is to engage all the key stakeholders involved in the decision-making and delivery of postpartum care. First, by engaging the payer (large Medicaid Managed group) and the health system leadership, we were able to secure the necessary funds to increase the resources available to clinicians to provide targeted care to high-risk postpartum women. Second, by harnessing the health system’s organizational infrastructure and resources (through their obstetrics and social work department), we were able to tailor the educational component to clinicians and training of social workers building on the strengths and progress already made in those departments over time. Finally, given that all the parties involved are vested in the success of this intervention, we have been able to access data from the health system, the payer and our ad-hoc collection of data that will allow us to uniquely assess the effectiveness of our intervention across a set of outcomes (health outcomes, utilization and cost) –which is not common in the literature.

III. Delivery System Reform

Our case management intervention builds on two successful case- management interventions at the health system. The first is a case management intervention sponsored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services that targets elderly patients at high risk for readmission based on comorbidities. All patients receive an initial assessment which includes full health care utilization history, psychosocial drivers of readmission, and connection with family. Post-discharge calls, home visits, primary care visits, and community resources are all provided to patients. This program successfully reduced readmissions among high risk elderly patients by over 40%.8

The second case management intervention was developed in a research setting and was designed to reduce postpartum depression through a two-step behavioral educational intervention. This intervention prepared and educated mothers about potential physical and emotional postpartum symptoms, bolstered social support, enhanced management skills, and increased access to community resources. A randomized trial demonstrated substantial benefits: one-third reduction in the odds of a positive depression screen and prolonged breastfeeding duration over a six-month period among black and Hispanic mothers.7,14

We combined the key mechanisms in these two interventions and provide education about health conditions (hypertension, diabetes, and depression), important health behaviors (nutrition and exercise) and common physical and emotional postpartum symptoms, teach self-management skills, enhance social support, connect patients with appropriate medical care and increase access to community resources. Our intervention combines the initial educational component with an initial assessment of postpartum women, a one to two-week call and additional calls depending on the needs of each patient. The social worker and the care coordinator help patients navigate the medical system, provide medication reconciliation, serve as an important educational resource, connect patients with community and internet resources, and aim to impact upstream factors associated with the health status of high risk postpartum women. The intervention is being implemented in English and Spanish.

In an effort to retain patients we provide flexibility with timing of follow-up assessments (two weeks, three weeks, and six months postpartum), tracking of date/time of follow-ups, use of technology (emails) to contact patients and send reminders, and use of mailings. In addition, we provide a small incentive ($10 gift card) for patients when they attend their postpartum visit.

IV. Payment Reform

The payment reform initiative aims to realign financial and nonfinancial incentives across the health system as a whole and directly to clinicians to help them meet postpartum care targets. At the system level, the incentives include a cost-sharing arrangement between the health system and the Medicaid managed care health insurance plan to cover expenditures related to employing a social worker and a care coordinator. Clinician/clinic-level financial incentives in the form of enhanced payments for completed postpartum visits by the payer were rolled out after the case management intervention had been implemented for 12 months.

Nonfinancial incentives include clinician education, increased resources to clinicians (in the form of care coordination), and performance feedback. We have provided clinician education to a large array of clinicians and staff including physicians, nurses, social workers, clinic staff, and registrars. This information has been conducted through thematic grand rounds, tailored education modules, as well as one-on-one meetings. The study team has provided an overview of the study as well as clinical information on postpartum care of gestational diabetes, hypertension, and depression.

V. Study Sample and Outcomes

We aim to recruit 510 postpartum women insured by our Medicaid managed care plan partner. Eligible patients include pregnant women who are 18 years of age or older, speak Spanish or English, and have gestational diabetes, hypertension, screen positive for depression, register late for prenatal care (>20 weeks) or reside in high risk neighborhoods for diabetes or hypertension according to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Daily reports of potentially eligible patients (patients insured by the Medicaid Managed Care partner) are produced by EPIC. Our study social worker and care coordinator then approach listed patients to assess final eligibility and consent then consent patients who meet the eligibility criteria described above.

Our primary outcome is the HEDIS timely postpartum care measure, an indicator utilized to determine whether a participant has a postpartum visit to an Ob/Gyn practitioner or midwife, family practitioner, or other primary care provider on or between 21 and 56 days after delivery.15 Our secondary outcomes include blood pressure monitoring in the first week postpartum for patients with hypertension, completion of fasting glucose screen at postpartum visit for women with a history of gestational diabetes, mother emergency department visits and hospital admissions in the first year postpartum, depression screen at three weeks and six months postpartum, and health care costs associated with the intervention.

VI. Assessments, Sample Size Calculation, and Progress to date

We conduct patient surveys at baseline, at three-weeks, and six-months postpartum. These surveys collect data on postpartum emotional and physical symptoms and functioning, interactions with the health care system, satisfaction, as well as self-report of many of the outcomes of interest. We also utilize data from electronic medical records as well as claims data from the Medicaid managed care health plan to evaluate and track our outcomes of interest.

Our sample size of 510 women has been determined to ensure that we may detect the impact of our intervention on the primary outcome of timely postpartum care with high probability, and also ensures adequate power to determine the intervention’s impact on several pre-specified secondary outcomes. With 510 women, we will be able to precisely estimate the postpartum visit rate, for example, the maximum half-width (i.e., margin of error) of the estimated 95% confidence would be less than 4.5%. The power to reject a null hypothesis that the true rate is not improved from our intervention (i.e., that the true rate of timely post-partum visits after intervention is 58% or less) is also adequate. With 510 women, we will have 90% power to detect differences as small as 7%.

Implementation

After 73 weeks of recruitment our study enrolled 468 patients and has two withdrawals. One hundred eighty-nine patients refused to participate. Of the enrolled patients, 95% were black or Latina women, 11% had gestational diabetes, 21% had hypertension, 6% were late registrants to prenatal care, 16% screened positive for depression, and over 90% resided in high risk neighborhoods for diabetes and hypertension. Our current HEDIS measure postpartum visit rate is 72%.

Our intervention involves the voluntary participation of women that will receive postpartum care. In order to improve our screening and recruitment process, we have collected open-ended response data on the reasons for refusal to participate. We have found that a number of women who refused were concerned about lack of time, competing demands, were not interested in research, were “too sick,” or felt they had already been through childbirth before and did not need our intervention.. We used this information to tailor and improve our screening and recruitment processes.

Key to our implementation strategy was finding appropriate strategies to align the internal financial infrastructure at the health care provider level (e.g., billing and reimbursement cycles) with our intervention’s aims. In particular, channeling financial incentives directly to clinicians (e.g., individual bonuses) was an unanticipated challenge, as these small incentives cannot be disbursed with the frequency we initially aimed for based on the behavioral economics literature. Indeed, the literature on the implementation of behavioral economics strategies at the provider level does not yet address directly some of these structural challenges. We believe our project and lessons learned will contribute to this important aspect of implementation.

The financial and technical infrastructure in the delivery care system proved challenging to the implementation of our project in some other ways. For example, our project required changes to existent billing codes in order to bill and reimburse the approved financial incentives. This required changes at both the provider/clinic level and changes to the Medicaid Managed codes as well. While this technical challenge was addressed, it does reflect standard challenges that systems may face when trying to replicate interventions such as ours.

Ultimately, leadership buy-in has been critical for our team’s ability to navigate the implementation challenges we have faced at the organizational, financial and technical levels. We have sought to incorporate provider feedback and engage providers in the important conversations about the challenges they face when delivering care for complex cases of postpartum care.

The strong focus of our project’s increased resources to clinicians (social worker and care coordination team) and educational components have been successful thus far at increasing provider awareness about the importance of having a postpartum care visits. However challenges related to providing information on actual clinical outcomes to physicians remain a challenge given the significant time lag in billing for postpartum visits and the barriers our team faced with the implementation of necessary changes to current billing practices.

VII. Next Steps

Our project engages key stakeholders involved at all stages of the flow of decision-making that can improve postpartum care for high-risk women from vulnerable populations. The managed care organization, our health system leadership, as well as our economics team, obstetricians, health disparities researchers, and others developed and planned this program together for a competitive research grant. Engagement of key stakeholders has continued through regular meetings with leadership in the Departments of Ob/Gyn and Social Work, our managed care organization partners, as well as with our team of economists. We believe the success of program such as this one requires regular discussions with all of the stakeholders and the alignment of the intervention with our health systems ongoing efforts in population health management.

For this program, we incorporated the existent evidence-base across multidisciplinary literatures on payment reform and delivery change. The payment reform and delivery system change we are testing allows for the alignment of payer/provider incentives and is informed by the collection of clinical and financial data at the health system and payer for continued improvement, translation, and dissemination.

Our intervention focuses on early identification and intervention in high-risk postpartum women, in an effort to minimize and/or prevent long-term consequences of costly chronic health conditions. Improving care for high-risk vulnerable postpartum women has the potential to also address long-term disparities in women’s health. Women with gestational diabetes have a greater than sevenfold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes,16 postpartum women with hypertension and preeclampsia are at increased risk for ischemic heart disease, chronic hypertension and stroke,17 and late entry to prenatal care is associated with elevated risk.18 Postpartum depression affects up to 20% of women and is associated with multiple adverse consequences for mothers and babies.19,20 Significant racial/ethnic disparities exist for all of these conditions, with black and Latina women versus white women having higher prevalence rates, experiencing a disproportionate burden of short and long term consequences from these diseases and characteristics and—in the case of postpartum depression—being one-half as likely to receive treatment.21–25 Thus, our intervention has the potential to impact both short and long term outcomes for vulnerable postpartum women and may be a step towards decreasing racial/ethnic disparities in postpartum women’s access to timely healthcare services.

Our evidence-based program focuses on an important area of maternal health, targets racial/ethnic disparities in postpartum care, utilizes an innovative payment reform strategy, implements an evidence-based case management intervention, and brings together insurers, researchers, clinicians, and policy experts to work together to foster health and wellness for postpartum women and reduce disparities.

Given the complexity of engaging many partners, and doing so in a timely fashion, there are not many examples in the literature. Our project design and implementation builds on all the available evidence. For this reason, our findings will not only improve on the literature of program design to reduce disparities, but also on the participatory design of these types of large interventions involving system-wide delivery and payment reform. We anticipate that our set of findings will be of interest to both the health system and payer, as the landscape of health care delivery moves towards a value-based model.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant #72257). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

VIII. References

- 1.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011: Statistical Brief #162. 2006 Feb; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant AS, Seely EW, Cohen A, Lieberman E. Patterns of pregnancy-related hypertension in black and white women. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2005;24(3):281–290. doi: 10.1080/10641950500281134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guendelman S, Thornton D, Gould J, Hosang N. Obstetric complications during labor and delivery: assessing ethnic differences in California. Womens Health Issues. 2006 Jul-Aug;16(4):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabacungan ET, Ngui EM, McGinley EL. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Morbidities: A Statewide Study of Labor and Delivery Hospitalizations in Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Nov 22; doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0914-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C. Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: A report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diabetes Care. 2009 Feb;32(2):269–274. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NCQA. 2014 Accreditation Benchmarks and Thresholds—Mid-Year Update. 2014 http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/PolicyUpdates/Trending%20and%20Benchmarks/2014_BENCHMARKSANDTHRESHOLDS.pdf.

- 7.Howell EA, Balbierz A, Wang J, Parides M, Zlotnick C, Leventhal H. Reducing postpartum depressive symptoms among black and Latina mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 May;119(5):942–949. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318250ba48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mount Sinai Faculty Practice. [Accessed April 15, 2014];Facts About Coordinated Care at Mount Sinai. 2014 www.mountsinaifpa.org/about-us/news-archive/facts-about-coordinate-care-at-mount-sinai.

- 9.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007 Dec 12;298(22):2623–2633. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willard-Grace R, DeVore D, Chen EH, Hessler D, Bodenheimer T, Thom DH. The effectiveness of medical assistant health coaching for low-income patients with uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: protocol for a randomized controlled trial and baseline characteristics of the study population. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melville JL, Reed SD, Russo J, et al. Improving care for depression in obstetrics and gynecology: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1237–1246. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 Jan-Feb;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truitt FE, Pina BJ, Person-Rennell NH, Angstman KB. Outcomes for collaborative care versus routine care in the management of postpartum depression. Qual Prim Care. 2013;21(3):171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell EA, Bodnar-Deren S, Balbierz A, Parides M, Bickell N. An intervention to extend breastfeeding among black and Latina mothers after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;210(3):239.e231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NCQA. HEDIS Measure Definition Postpartum Care. 2014 https://www.ncqa.org/ReportCards/HealthPlans/StateofHealthCareQuality/2014TableofContents/PerinatalCare.aspx.

- 16.Stasenko M, Liddell J, Cheng YW, Sparks TN, Killion M, Caughey AB. Patient counseling increases postpartum follow-up in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;204(6):522.e521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed R, Dunford J, Mehran R, Robson S, Kunadian V. Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Risk among Women: A Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 21; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui R, Bell T, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Minard C, Levison J. Predictive factors for loss to postpartum follow-up among low income HIV-infected women in Texas. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014 May;28(5):248–253. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Impove Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. Paper presented at: Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozhimannil KB, Pereira MA, Harlow BL. Association between diabetes and perinatal depression among low-income mothers. JAMA. 2009 Feb 25;301(8):842–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorpe LE, Berger D, Ellis JA, et al. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in gestational diabetes among pregnant women in New York City, 1990–2001. Am J Public Health. 2005 Sep;95(9):1536–1539. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentley-Lewis R, Powe C, Ankers E, Wenger J, Ecker J, Thadhani R. Effect of race/ethnicity on hypertension risk subsequent to gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2014 Apr 15;113(8):1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savitz DA, Danilack VA, Engel SM, Elston B, Lipkind HS. Descriptive epidemiology of chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia in new york state, 1995–2004. Matern Child Health J. 2014 May;18(4):829–838. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1307-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozhimannil KB, Trinacty CM, Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Adams AS. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum depression care among low-income women. Psychiatr Serv. 2011 Jun;62(6):619–625. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.6.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H. Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jun;105(6):1442–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164050.34126.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]