Abstract

Black and Hispanic (minority) MSM have a higher incidence of HIV than white MSM. Multiple sexual partners, being under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol during sex, having a detectable HIV-1 RNA, and non-condom use are factors associated with HIV transmission. Using data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study, we consider minority status and sexual orientation jointly to characterize and compare these factors. White non-MSM had the lowest prevalence of these factors (p<0.001) and were used as the comparator group in calculating odds ratios (OR). Both MSM groups were more likely to report multiple sex partners (white MSM OR: 7.50; 95% CI 5.26, 10.71; minority MSM OR: 10.24; 95% CI 7.44, 14.08), and more likely to be under the influence during sex (white MSM OR: 2.15; 95% CI 1.49, 3.11; minority MSM OR: 2.94; 95% CI 2.16, 4.01). Only minority MSM were more likely to have detectable HIV-1 RNA (OR: 1.87; 95% CI 1.12, 3.11). Both MSM groups were more likely to use condoms than white non-MSM. These analyses suggest that tailored interventions to prevent HIV transmission among minority MSM are needed, with awareness of the potential co-occurrence of risk factors.

Keywords: health, minority, MSM, HIV transmission, alcohol-related disorders

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has long recognized minority (black and Hispanic) men who have sex with men (MSM) as a distinct and important group for which tailored interventions may be required.(1) The lifetime risk of HIV is 1 in 2 and 1 in 4 for black and Hispanic MSM, respectively, compared to 1 in 11 for white MSM.(1) In 2016, the National Institutes of Health Office of AIDS Research (NIH OAR) listed minority MSM among its high priority research area. While a decrease in HIV cases has been seen over the years in white MSM there has been an increase in incidence among minority MSM, especially young minority MSM.(1–4) Of special concern, CDC 2011 data indicate that only 28% of black MSM living with HIV achieved viral suppression.(1) Interventions to prevent HIV transmission have fallen short among minority MSM possibly because of cultural distinctions among white and black MSM.(5) Stigma, access to health care, discrimination and homophobia are experienced differently by minority groups and these all contribute to disparities in HIV diagnoses and treatment.(6–8)

Well established risk factors for sexual transmission of HIV are multiple partners, substance use, detectable HIV-1 RNA, and non-condom use.(9, 10) Alcohol and drug use (substance use) compounds sexual risk behaviors by lowering inhibition, increasing impulsivity and impairing judgement.(11–13) Those under the influence of drugs or alcohol may have sex more often than intended, or with more people than intended, and may fail to use a condom.(14,15) Those with HIV-infection who use substances are also less likely to adhere to antiretroviral therapy and more likely to have detectable HIV-1 RNA. Prior papers were largely before combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and were limited in examining viral load.

Among sexually active men in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS), we consider minority status and sexual orientation (i.e. MSM) jointly to characterize and compare risk factors for HIV transmission. Risk factors included: 1) multiple sexual partners, 2) sex while under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol use, 3) having a detectable HIV-1 RNA viral load and 4) non-condom use. We hypothesized that minority MSM would be more likely to report sexual risk factors after adjusting for relevant covariates, including unhealthy alcohol use, and that these covariates may partially attenuate the association.

Methods

Study population and data source

The Veterans’ Aging Cohort Study (VACS) survey study is described in detail elsewhere.(16) In brief, VACS survey study is an on-going longitudinal prospective multi-site observational study representing 3631 HIV-infected and 3693 uninfected persons. Data used for this analysis were based on baseline data from 2002 to 2008. At baseline enrollment, participants completed surveys and provided permission to access electronic medical records. HIV-infected participants were matched to uninfected participants on age, race/ethnicity, and geographical site of care. Participants in VACS are demographically representative of HIV-infected Veterans in care.(16) VACS was Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved at the coordinating center at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System and the VA of participating sites.

The study sample for these analyses included the subset of men from VACS who completed a baseline survey and reported any sexual activity in the past year (n=4506). Data were obtained from participant baseline surveys and electronic medical records. Further descriptions of the VACS survey sample and methodology are available online (www.vacohort.org).

Measures

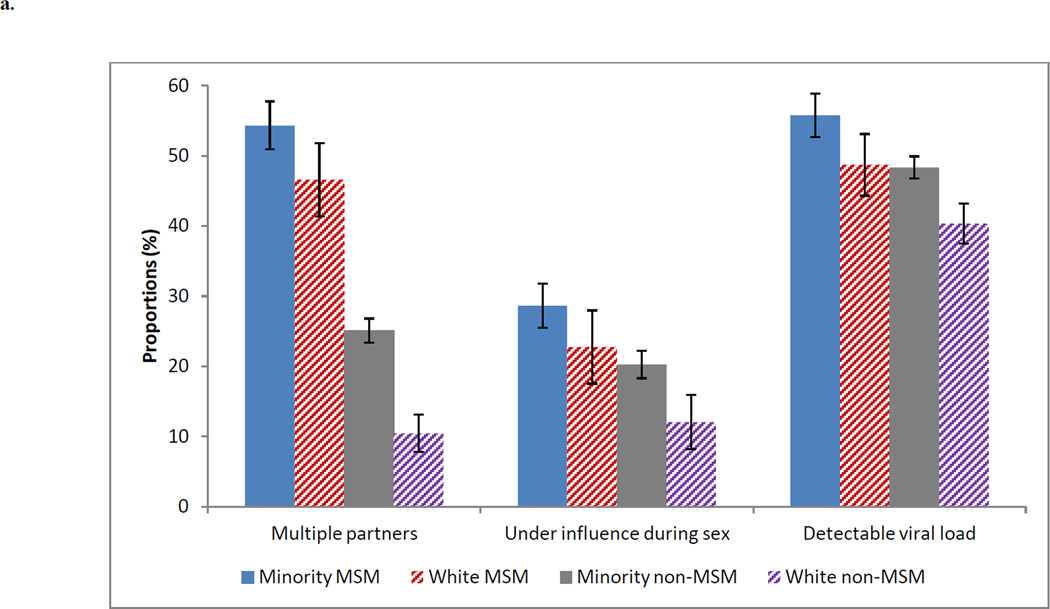

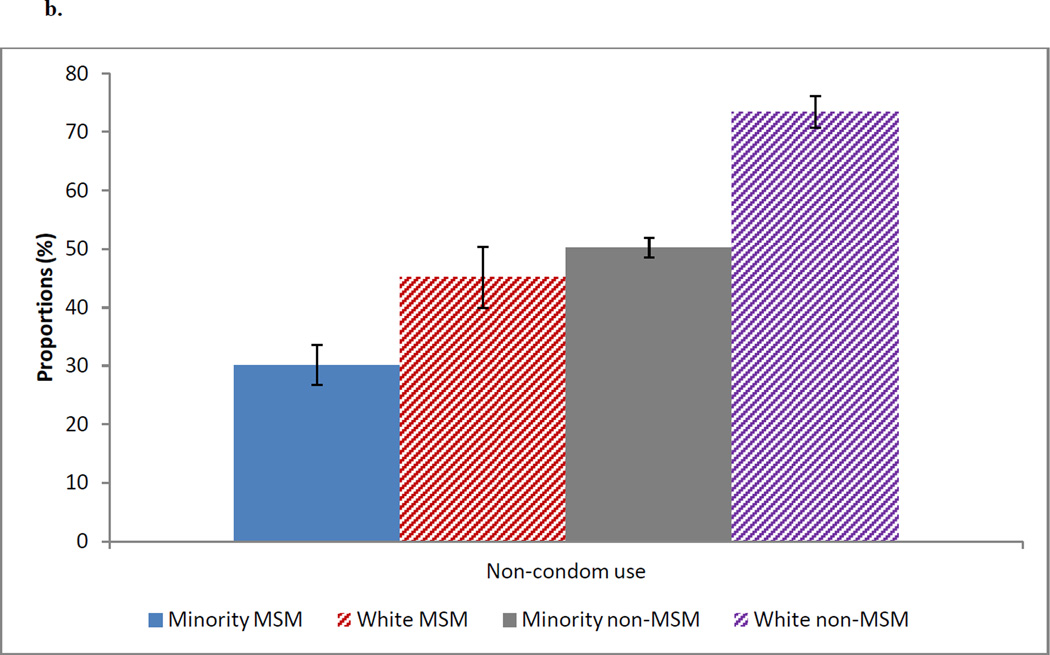

Our outcomes of interest were the following factors associated with HIV transmission: 1) multiple partners, defined as reporting more than two sexual partners in the past 12 months, which is based on the question “During the past 12 months, with how many people have you had sex?”, for which participant entered a number, 2) being under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol during sex at last sexual encounter, which is based on “Thinking back about the last time you had sex, were you under the influence of alcohol or drugs?”, choice set yes/no, 3) among HIV-infected participants, having a detectable HIV-1 RNA at baseline (i.e. enrollment), defined as ≥ 500 copies/mL, and 4) self-reported non-condom use at last sexual encounter, which is based on “Thinking back about the last time you had sex, did you or your partner use a condom?”, choice set yes/no. Our primary independent variable was the joint characteristics of MSM and race, categorized into a four level composite variable: minority MSM, white MSM, minority non-MSM, and white non-MSM. Because white non-MSM had the lowest prevalence of all factors, except non-condom use (Figure 1a and 1b), white non-MSM were used as the comparator group in calculating odds ratios (OR). Race/ethnicity was based on self report and included white and minority (black and Hispanic) race. Black and Hispanics were grouped together due to the fact that both populations experience higher rates of HIV infection than whites, and because the sample of Hispanic MSM was too small to examine separately. Our primary interest was minority versus white, so the small proportion reporting mixed or other races (4%) were excluded. MSM was based on male participant reporting having sex in the past 12 months with men only or both men and women. A secondary predictor of interest was levels of alcohol use, defined as not a current drinker, non-hazardous drinker, hazardous/binge drinker, and alcohol abuse and/or dependence. Unhealthy alcohol use, a spectrum that includes at-risk, binge and alcohol use disorders,(17) leads to increased sexual risk behavior, poor medication adherence, condom failure, and progression of the disease resulting in increased HIV transmission and worsening health outcomes.(18–20) Additionally, recent studies show that HIV-infected persons are affected by alcohol at lower dosage. (19, 21) Thus, minority MSM with unhealthy alcohol use may be at higher risk for HIV infection, and among those infected, may be at higher risk for transmitting the virus to others. Not a current drinker was defined as no report of drinking for more than 12 months; non-hazardous drinker was based on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)(22) score <3 for women and < 4 for men in the past 12 months (thus hazardous was AUDIT-C score≥3 and ≥4 respectively); binge or heavy episodic drinking was defined as reporting 6 or more drinks on one occasion at least monthly; and alcohol abuse and/or dependence was defined using 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient International Statistical Classification of Disease version 9 (ICD-9) codes consistent with alcohol-related diagnosis a year prior and up to 6 months after enrollment. Other covariates of interest included age, HIV status, hepatitis C (HCV) infection, major depression, homelessness, relationship status (married, divorced, separated, widowed, never married, and living with a partner), annual income (dichotomized ≥ $12,000 US vs. < $12,000 US based on the US Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for 2013 for an individual, which is $11,888 US (23) and was rounded to $12,000 for simplicity), education (high school graduate or higher, yes/no), CD4 cell count at baseline, and HIV viral load at baseline. Homelessness, income, education and relationship status were self-reported, while major depression and drug abuse and/or dependence were based on ICD-9 code. HCV was based on ICD-9 codes and laboratory data. Among uninfected participants, self-perceived HIV risk, “Do you think you are at risk for HIV infection?”, and prior testing, “Have you ever been tested for HIV?”, were included. Self-perceived risk was assessed on a Likert scale of 0 – 4 and categorized for simplicity as low 0–1, moderate 2 and high 3–4. Among HIV-infected, we looked at adherence at baseline to HIV antiretroviral therapy, defined as 90% threshold of fill/refill using pharmacy prescription data a year prior and up to enrollment date.(24)

Figure 1.

a. Proportion of Participants with Joint Characteristics of MSM and Race who Reported Multiple Partner, Under the Influence During Sex, and Detectable HIV Viral Load (≥500)

b. Proportion of Participants with Joint Characteristics of MSM and Race who Reported Non-condom Use

Of the 4506 male participants who reported sexual activity in the past 12 months, 4146 (92%) had complete survey and administrative data. The participants who did not have complete information (n=360), compared to those who did, were more likely to be minority (85% vs. 80%, p=0.04). They were less likely to report an annual income of $12,000 US or more (48% vs. 57%, p=0.01), and less likely to be a high school graduate or higher (86% vs. 93%, p<0.001). Among HIV-infected, they had lower median CD4 cell count (354 vs. 380, p=0.05). Our study was approved by the IRB of the VA Connecticut Healthcare System and Yale University School of Medicine.

Analyses

Using baseline data, we conducted descriptive analyses of demographic and clinical characteristics overall, by HIV status and by sexual risk behaviors. Because undetectable HIV viral load was assessed among a subset of participants (HIV-infected), the bivariate results are reported within the text and not in a table. We used t-test for continuous variables, or a nonparametric counterpart, Wilcoxon test, for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and chi-square for categorical variables. We then assessed the relationship between the composite variable of MSM and race and the four factors associated with HIV transmission (multiple partners, under the influence during sex, detectable HIV viral load, and non-condom use) in a logistic regression model. In adjusted models, we included variables found to be significant (p<0.05) in bivariate analyses; unless they were collinear (Spearman coefficient >0.50). Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.3.1

Results

Description of sample

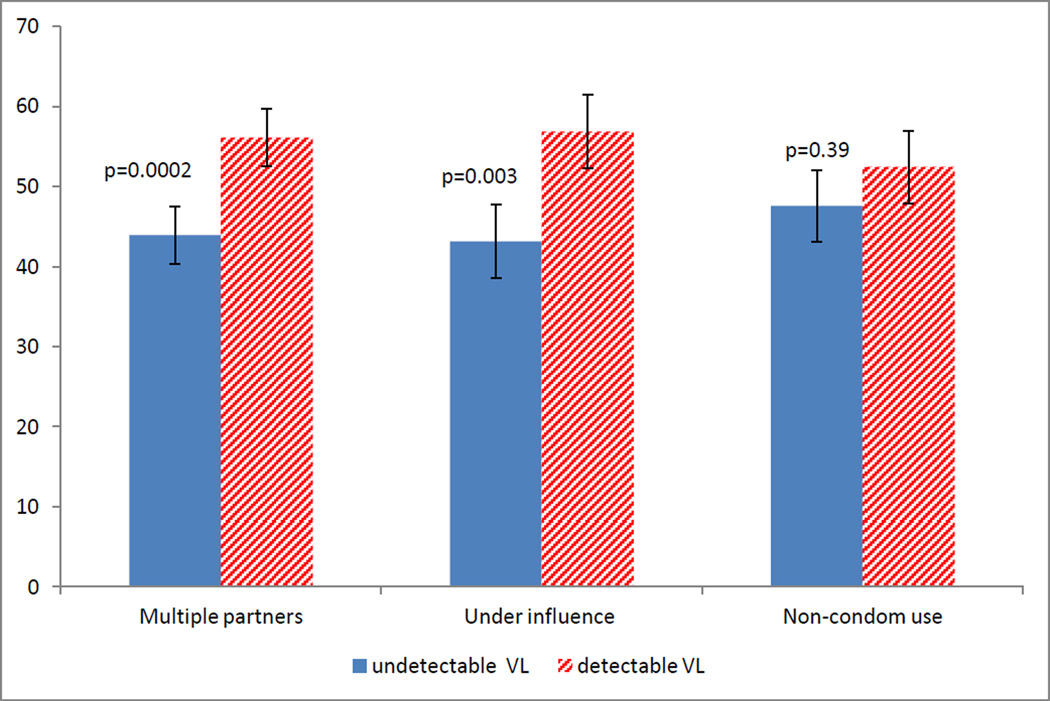

In our analytic sample of 4146 individuals, the mean and median age were 49 years old, 48% were HIV-infected, 20% were minority MSM, 8% were white MSM, 60% were minority non-MSM, and 12% were white non-MSM (Table 1a). Thirty-two percent were not currently drinking, 29% were non-hazardous drinkers, 26% were hazardous and/or binge drinkers, 14% had diagnoses consistent with alcohol abuse and/or dependence and 23% had drug abuse and/or dependence. Thirty-seven percent of participants were HCV infected, 10% had major depression, 48% reported being homeless, 26% were married, and 10% lived with a partner. Thirty-one percent reported having multiple partners, 21% reported being under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol the last time they had sex, 51% (among HIV-infected) had a detectable HIV-1 RNA viral load, and 49% reported non-condom use. Among the uninfected, 18% reported being at moderate to high risk for HIV. Among HIV-infected, only 47% were adherent to HIV therapy. A significant proportion of HIV-infected participants who reported multiple partners and sex under the influence had detectable HIV-1 RNA viral load (Figure 2, 56% and 57%, respectively); a co-occurrence of risk factors.

Table 1a.

Descriptive Statistics on Sexually Active Male Participants in the Veteran’s Aging Cohort Study

| Variables | n=4146 | Uninfected, n=2146 |

HIV-infected, n=2000 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean(SD) | 49 (9) | 50 (9) | 48 (8) | <0.001 |

| IQR | 49 (43, 54) | 49 (44, 55) | 48 (42, 54) | <0.001 |

| MSMa | <0.001 | |||

| non-MSM | 2984 (72) | 2015 (94) | 969 (48) | |

| MSM | 1162 (28) | 131 (6) | 1031 (52) | |

| Race | 0.04 | |||

| White | 848 (20) | 468 (22) | 380 (19) | |

| Black | 2880 (69) | 1453 (68) | 1427 (71) | |

| Hispanic | 418 (10) | 225 (10) | 193 (10) | |

| MSMa and race | <0.001 | |||

| Minority MSM | 814 (20) | 96 (4) | 718 (36) | |

| White MSM | 348 (8) | 35 (2) | 313 (16) | |

| Minority non-MSM | 2484 (60) | 1582 (74) | 902 (45) | |

| White non-MSM | 500 (12) | 433 (20) | 67 (3) | |

| Levels of alcohol use | <0.001 | |||

| Not current drinker | 1313 (32) | 686 (32) | 627 (31) | |

| Non-hazardous drinker | 1190 (29) | 558 (26) | 632 (32) | |

| Hazardous†/binge* drinker | 1066 (26) | 550 (26) | 516 (26) | |

| Alcohol abuse & dependence | 577 (14) | 352 (16) | 225 (11) | |

| Drug abuse | 973 (23) | 530 (25) | 443 (22) | 0.05 |

| Hepatitis C | 1514 (37) | 583 (27) | 931 (47) | <0.001 |

| Major depression | 430 (10) | 233 (11) | 197 (10) | 0.29 |

| Homelessness | 1980 (48) | 944 (44) | 1036 (52) | <0.001 |

| Relationship Status | <0.001 | |||

| Married | 1083 (26) | 781 (36) | 302 (15) | |

| Divorce | 1058 (26) | 582 (27) | 476 (24) | |

| Separated | 460 (11) | 232 (11) | 228 (11) | |

| Widowed | 136 (3) | 56 (3) | 80 (4) | |

| Never married | 1012 (24) | 335 (16) | 677 (34) | |

| Living with a partner | 397 (10) | 160 (7) | 237 (12) | |

| Income (=>$12,000) | 2370 (57) | 1320 (62) | 1050 (53) | <0.001 |

| High school graduate or higher | 3847 (93) | 1971 (93) | 1876 (94) | 0.08 |

| HIV status | ||||

| uninfected | 2146 (52) | |||

| HIV-infected | 2000 (48) | |||

| Have you ever been tested for HIV?t | ||||

| No | 525 (24) | 525 (24) | ||

| Yes | 1606 (75) | 1606 (75) | ||

| missing | 15 (1) | 15 (1) | ||

| Do you think you are at risk for HIV?t | ||||

| Low (0–1) | 1752 (82) | 1752 (82) | ||

| Moderate (2) | 324 (15) | 324 (15) | ||

| High (3–4) | 56 (3) | 56 (3) | ||

| Highly active antiretroviral therapy** | 1400 (70) | 1400 (70) | ||

| Adherenced ** | 690 (47) | 690 (47) | ||

| Viral load**: | ||||

| HIVRNA < 500 copies/mL | 948 (49) | 948 (49) | ||

| HIVRNA≥ 500 copies/mL | 975 (51) | 975 (51) | ||

| CD4**, IQR | 380 (234, 568) | 380 (234, 568) | ||

| Multiple partnersm | 1278 (31) | 506 (24) | 772 (39) | <0.001 |

|

Sex under the influence of drugs

and/or alcohol |

874 (21) | 399 (19) | 475 (24) | <0.001 |

| Non-condom use | 2016 (49) | 1526 (71) | 490 (25) | <0.001 |

Column % except where noted

MSM was defined as Male who reported they had sex with males or males & females

hazardous drinking is defined using AUDIT_C, ≥3 for women and ≥4 for men

Binge is reporting 6 or more drinks on one occasion

among uninfected only

Among HIV+ only

Defined as 90% or more from fill/refill data

Multiple sex partners was based on the question: During the past 12 months, with how many people have you had sex? Where >2 was considered multiple

Figure 2.

Proportion of Participants with Risk Behaviors by Detectable HIV Viral Load

HIV-infected compared to uninfected were more likely to be minority MSM (36% vs 4%, p<0.001), to report multiple sexual partners (39% vs. 24%, p<0.001), and to be under the influence of drug and/or alcohol during sex (24% vs. 19%, p<0.001) (Table 1a). Uninfected were almost three times as likely as HIV-infected participants to report non-condom use (71% vs. 25%, p<0.001).

In bivariate analyses, age, HIV, MSM and race, alcohol use, drug use, homelessness, relationship status, and income were associated with all 4 risk factors associated with HIV transmission. HCV was associated with being under the influence during sex and non-condom use (Table 1b). Major depression was associated with being under the influence during sex, and borderline associated with multiple sex partners. High school graduate or higher was associated with multiple partners (Table 1b). Participants with a detectable HIV viral load, compared to those with undetectable HIV viral load, were more likely to be minority MSM (39% vs. 32%, p=0.006), have alcohol abuse and/or dependence (14% vs. 9%, p=0.001), divorced (26% vs. 21%, p=0.0004) and homeless (54% vs. 48%, p=0.01). They were also younger (46 vs. 49 years old, <0.001), less likely to have HCV (44% vs. 49%, p=0.03), less likely to be adherent to HIV therapy (39% vs. 55%, p<0.001), among the 70% on cART at baseline, and had lower median CD4 count (323 vs. 441, p<0.001). Covariates significantly associated with any risk factors were included in all the regression models.

Table 1b.

Descriptive Statistics on Sexually Active Male Participants in the Veteran’s Aging Cohort Study by Sexually Risk Factors

| Multiple partnersm | Under the influence during sex | Non-condom use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No, n=2868 |

Yes, n=1278 |

p value |

No, n=3272 |

Yes, n=874 |

p value |

No, n=2130 |

Yes, n=2016 |

p value |

| Age, mean (SD) | 50 (9) | 47 (9) | <0.001 | 49 (9) | 48 (7) | 0.001 | 48 (9) | 49 (9) | 0.001 |

| HIV status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| uninfected | 1640 (57) | 506 (40) | 1747 (53) | 399 (46) | 620 (29) | 1526 (76) | |||

| HIV-infected | 1228 (43) | 772 (60) | 1525 (47) | 475 (54) | 1510 (71) | 490 (24) | |||

| MSMa and race | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Minority MSM | 372 (13) | 442 (35) | 581 (18) | 233 (27) | 569 (27) | 245 (12) | |||

| White MSM | 186 (6) | 162 (13) | 269 (8) | 79 (9) | 191 (9) | 157 (8) | |||

| Minority non-MSM | 1862 (65) | 622 (49) | 1982 (61) | 502 (57) | 1237 (58) | 1247 (62) | |||

| White non-MSM | 448 (16) | 52 (4) | 440 (13) | 60 (7) | 133 (6) | 367 (18) | |||

| Levels of alcohol use | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Not current drinker | 993 (35) | 320 (25) | 1216 (37) | 97 (11) | 698 (33) | 615 (31) | |||

| Non-hazardous drinker | 846 (30) | 344 (27) | 1035 (32) | 155 (18) | 641 (30) | 549 (27) | |||

| Hazardous†/binge* drinker | 698 (24) | 368 (29) | 733 (22) | 333 (38) | 494 (23) | 572 (28) | |||

| Alcohol abuse & dependence | 331 (12) | 246 (19) | 288 (9) | 289 (33) | 297 (14) | 280 (14) | |||

| Drug abuse | 582 (20) | 391 (31) | <0.001 | 572 (17) | 401 (46) | <0.001 | 527 (25) | 446 (22) | 0.05 |

| Hepatitis C | 1042 (36) | 472 (37) | 0.71 | 1089 (33) | 425 (49) | <0.001 | 890 (42) | 624 (31) | <0.001 |

| Major depression | 281 (10) | 149 (12) | 0.07 | 298 (9) | 132 (15) | <0.001 | 220 (10) | 210 (10) | 0.93 |

| Homelessness | 1237 (43) | 743 (58) | <0.001 | 1372 (42) | 608 (70) | <0.001 | 1079 (51) | 901 (45) | 0.0001 |

| Relationship status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married | 990 (35) | 93 (7) | 981 (30) | 102 (12) | 329 (15) | 754 (37) | |||

| Divorce | 667 (23) | 391 (31) | 787 (24) | 271 (31) | 593 (28) | 465 (23) | |||

| Separated | 298 (10) | 162 (13) | 341 (10) | 119 (14) | 268 (13) | 192 (10) | |||

| Widowed | 94 (3) | 42 (3) | 104 (3) | 32 (4) | 93 (4) | 43 (2) | |||

| Never married | 523 (18) | 489 (38) | 733 (22) | 279 (32) | 670 (31) | 342 (17) | |||

| Living with a partner | 296 (10) | 101 (8) | 326 (10) | 71 (8) | 177 (8) | 220 (11) | |||

| Income (=>$12,000) | 1732 (60) | 638 (50) | <0.001 | 2002 (61) | 368 (42) | <0.001 | 1097 (52) | 1273 (63) | <0.001 |

| High school graduate or higher | 2642 (93) | 1205 (95) | 0.006 | 3043 (94) | 804 (93) | 0.42 | 1971 (93) | 1876 (94) | 0.84 |

| Have you ever been tested for HIV?t | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||

| No | 462 (28) | 63 (12) | 461 (26) | 64 (16) | 121 (20) | 404 (26) | |||

| Yes | 1166 (71) | 440 (87) | 1274 (73) | 332 (83) | 494 (80) | 1112 (73) | |||

| missing | 12 (1) | 3 (1) | 12 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 10 (1) | |||

|

Do you think you are at risk

for HIV?t |

<0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | ||||||

| Low (0–1) | 1437 (88) | 315 (63) | 1488 (86) | 264 (67) | 480 (78) | 1272 (84) | |||

| Moderate (2) | 165 (10) | 159 (32) | 2116 (12) | 108 (27) | 118 (19) | 206 (14) | |||

| High (3–4) | 26 (2) | 30 (6) | 34 (2) | 22 (6) | 15 (2) | 41 (3) | |||

|

Highly active

antiretroviral therapy** |

889 (72) | 511 (66) | 0.003 | 1093 (72) | 307 (65) | 0.004 | 1064 (70) | 336 (69) | 0.43 |

| Adherenced ** | 451 (48) | 239 (46) | 0.45 | 571 (49) | 119 (39) | 0.001 | 538 (48) | 152 (45) | 0.29 |

| Viral load** | 0.0002 | 0.003 | 0.39 | ||||||

| HIVRNA < 500 copies/mL | 624 (53) | 324 (44) | 753 (51) | 195 (43) | 723 (50) | 225 (48) | |||

| HIVRNA ≥ 500 copies/mL | 561 (47) | 414 (56) | 718 (49) | 257 (57) | 727 (50) | 248 (52) | |||

| CD4**, IQR | 376 (232, 565) |

385 (242, 574) |

0.41 | 392 (243, 580) |

353 (196, 522) |

0.001 | 380 (234, 568) |

385 (232, 567) |

0.78 |

Column % except where noted

Multiple sex partners was based on the question: During the past 12 months, with how many people have you had sex? Where >2 was considered multiple

MSM was defined as Male who reported they had sex with males or males & females

hazardous drinking is defined using AUDIT_C, ≥3 for women and ≥4 for men

Binge is reporting 6 or more drinks on one occasion

among uninfected only

Among HIV+ only

Defined as 90% or more from fill/refill data

Factors Associated with Multiple Partners, being Under the Influence during Sex, Detectable HIV Viral Load and Non-Condom Use

Multiple partners

In unadjusted models, both minority MSM and white MSM status, compared to white non-MSM, showed a strong association with multiple partners (Table 2a, minority MSM OR: 10.24; 95% CI 7.44, 14.08; white MSM OR: 7.50; 95% CI 5.26, 10.71). When substance use (alcohol and drug) was added to the model, the association was reduced but minority MSM remained the strongest factor (OR: 9.96; 95% CI 7.22, 13.74). A reduction in effect size was also observed when relationship status was added in separately (data not shown). In the adjusted model, both minority MSM and white MSM status continued to be significantly associated with multiple partners in the presence of all other covariates, though the association diminished (minority MSM OR: 6.21; 95% CI 4.33, 8.92; white MSM OR: 5.92; 95% CI 3.96, 8.85). Higher levels of alcohol use were also associated with multiple partners. Compared to not current drinker, those who reported hazardous/binge drinking were 45% more likely to have multiple partners, and those with alcohol abuse and/or dependence were 66% more likely. Other positively associated factors were drug use, homelessness and not being married.

Table 2a.

Logistic Regressions Assessing the Association between Multiple Sexual Partners and Participant’s Characteristics

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters: | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value |

| White non-MSM (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a |

| Minority MSM | 10.24 (7.44, 14.08) | <0.001 | 9.96 (7.22, 13.74) | <0.001 | 6.21 (4.33, 8.92) | <0.001 |

| White MSM | 7.50 (5.26, 10.71) | <0.001 | 7.97 (5.56, 11.42) | <0.001 | 5.92 (3.96, 8.85) | <0.001 |

| Minority non-MSM | 2.88 (2.13, 3.89) | <0.001 | 2.60 (1.92, 3.52) | <0.001 | 2.16 (1.57, 2.97) | <0.001 |

| Not a current drinker (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | ||

| non-Hazardous | 1.09 (0.90, 1.32) | 0.39 | 1.05 (0.85, 1.28) | 0.67 | ||

| Hazardous/Binge | 1.64 (1.36, 1.98) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.19, 1.77) | 0.0003 | ||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 1.80 (1.41, 2.30) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.29, 2.14) | <0.001 | ||

| Drug abuse/dependence | 1.63 (1.34, 1.98) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.03, 1.58) | 0.02 | ||

| HIV-infection | 0.93 (0.78, 1.12) | 0.44 | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | 0.22 | ||||

| Age (10 year increments) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.85) | <0.001 | ||||

| Major Depression | 0.79 (0.62, 1.01) | 0.06 | ||||

| Homelessness | 1.39 (1.18, 1.64) | <0.001 | ||||

| Married (reference group) | 1 | n/a | ||||

| Divorce | 4.58 (3.53, 5.93) | <0.001 | ||||

| Separated | 4.18 (3.09, 5.66) | <0.001 | ||||

| Widowed | 4.86 (3.11, 7.58) | <0.001 | ||||

| Never married | 5.25 (4.03, 6.84) | <0.001 | ||||

| Living with a partner | 2.02 (1.45, 2.81) | <0.001 | ||||

| Income≥$12,000 US | 0.91 (0.77, 1.07) | 0.24 | ||||

Model adjusted for alcohol & drug abuse

Adjusted for other covariates of interest (HIV, Hepatitis C, depression, age, homelessness, relationship status, and income)

Sex under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol

In unadjusted models both minority and white MSM status were significantly associated with being under the influence of drug and/or alcohol during sex (Table 2b, minority MSM OR: 2.94; 95% CI 2.16, 4.01; white MSM OR: 2.15; 95% CI 1.49, 3.11). When substance use and relationship status were added to the model separately, the association diminished but remained positive and significant. In the adjusted model, both minority and white MSM status remained positive and significantly associated with being under the influence during sex (minority MSM OR: 1.97; 95% CI 1.35, 2.88; white MSM OR: 2.01; 95% CI 1.30, 3.12) (Table 2b). Any alcohol, HCV and not being married were also associated.

Table 2b.

Logistic Regressions Assessing the Association between being Under the Influence During Sex and Participant’s Characteristics

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters: | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value |

| White non-MSM (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a |

| Minority MSM | 2.94 (2.16, 4.01) | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.95, 3.81) | <0.001 | 1.97 (1.35, 2.88) | 0.0005 |

| White MSM | 2.15 (1.49, 3.11) | <0.001 | 2.50 (1.69, 3.70) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.30, 3.12) | 0.002 |

| Minority non-MSM | 1.86 (1.39, 2.47) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.07, 1.97) | 0.018 | 1.18 (0.85, 1.63) | 0.31 |

| Not a current drinker (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | ||

| non-Hazardous | 2.05 (1.56, 2.71) | <0.001 | 2.40 (1.81, 3.19) | <0.001 | ||

| Hazardous/Binge | 6.83 (5.29, 8.83) | <0.001 | 7.49 (5.75, 9.75) | <0.001 | ||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 6.90 (5.18, 9.19) | <0.001 | 6.78 (5.07, 9.06) | <0.001 | ||

| Drug abuse/dependence | 3.28 (2.63, 4.07) | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.77, 2.83) | <0.001 | ||

| HIV-infection | 1.00 (0.82, 1.23) | 0.97 | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 1.37 (1.13, 1.64) | 0.001 | ||||

| Age (10 year increments) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) | 0.66 | ||||

| Major Depression | 0.94 (0.72, 1.22) | 0.64 | ||||

| Homelessness | 1.92 (1.59, 2.33) | <0.001 | ||||

| Married (reference group) | 1 | n/a | ||||

| Divorce | 2.08 (1.58, 2.74) | <0.001 | ||||

| Separated | 2.02 (1.45, 2.82) | <0.001 | ||||

| Widowed | 2.24 (1.36, 3.69) | 0.002 | ||||

| Never married | 2.21 (1.66, 2.94) | <0.001 | ||||

| Living with a partner | 1.37 (0.95, 1.97) | 0.09 | ||||

| Income≥$12,000 US | 0.83 (0.69, 1.00) | 0.05 | ||||

Model adjusted for alcohol & drug abuse

Adjusted for other covariates of interest (HIV, Hepatitis C, depression, age, homelessness, relationship status, and income)

Undetectable HIV viral load

Among HIV-infected, minority MSM status, but not white MSM status, was associated with having a detectable HIV viral load in the unadjusted model (Table2c, OR: 1.87; 95% CI 1.12, 3.11). When substance use was introduced into the model, the statistically significant coefficient associated with minority MSM status and detectable HIV viral load was reduced (OR: 1.79; 95% CI 1.07, 2.99). This was also observed when relationship status was added to the model separately (data not shown). In the full adjusted model, minority MSM was not statistically significant. Non-hazardous alcohol use, alcohol abuse/dependence, homelessness, and divorce were positively and significantly associated with having a detectable HIV viral load.

Table 2c.

Logistic Regressions Assessing the Association between Detectable HIV Viral Load (≥500) and Participant’s Characteristics among HIV-infected

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value | AOR (95% CI) | p value |

| White non-MSM (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a |

| Minority MSM | 1.87 (1.12, 3.11) | 0.02 | 1.79 (1.07, 2.99) | 0.03 | 1.31 (0.76, 2.24) | 0.33 |

| White MSM | 1.40 (0.82, 2.41) | 0.22 | 1.35 (0.78, 2.32) | 0.28 | 1.15 (0.65, 2.03) | 0.62 |

| Minority non-MSM | 1.38 (0.83, 2.29) | 0.21 | 1.38 (0.83, 2.29) | 0.22 | 1.28 (0.76, 2.16) | 0.35 |

| Not a current drinker (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | ||

| non-Hazardous | 1.35 (1.07, 1.70) | 0.01 | 1.27 (1.00, 1.61) | 0.05 | ||

| Hazardous/Binge | 1.36 (1.07, 1.73) | 0.01 | 1.20 (0.93, 1.53) | 0.16 | ||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 1.99 (1.40, 2.82) | 0.0001 | 1.84 (1.29, 2.63) | 0.001 | ||

| Drug abuse/dependence | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | 0.63 | 0.91 (0.69, 1.19) | 0.48 | ||

| Hepatitis C | 0.87 (0.71, 1.07) | 0.18 | ||||

| Age (10 year increments) | 0.67 (0.60, 0.76) | <0.001 | ||||

| Major Depression | 0.92 (0.67, 1.26) | 0.59 | ||||

| Homelessness | 1.25 (1.02, 1.54) | 0.03 | ||||

| Married (reference group) | 1 | n/a | ||||

| Divorce | 1.83 (1.34, 2.50) | 0.0002 | ||||

| Separated | 1.16 (0.81, 1.67) | 0.42 | ||||

| Widowed | 1.61 (0.96, 2.71) | 0.07 | ||||

| Never married | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) | 0.07 | ||||

| Living with a partner | 1.40 (0.96, 2.04) | 0.08 | ||||

| Income≥$12,000 US | 0.88 (0.72, 1.07) | 0.20 | ||||

Model adjusted for alcohol & drug abuse

Adjusted for other covariates of interest (HIV, Hepatitis C, depression, age, homelessness, relationship status, and income)

Non-condom use

In unadjusted models white non-MSM were more likely to fail to use a condom (i.e. non-condom use) than minority MSM and white MSM (OR for non-condom use: minority MSM OR: 0.16; 95% CI 0.12, 0.20; white MSM OR: 0.30 95% CI 0.22, 0.40), and remained so in the presence of substance use (Table 2d). In the adjusted model, minority MSM was not significant. However, white MSM were more likely to fail to use a condom. Uninfected were more likely to fail to use a condom also. Hazardous/binge drinking was positively and significantly associated with non-condom use.

Table 2d.

Logistic Regressions Assessing the Association between Non-condom use and Participant’s Characteristics

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Adjusted2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters: | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value | ORs (95% CI) | p value |

| White non-MSM (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a |

| Minority MSM | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.75, 1.40) | 0.90 |

| White MSM | 0.30 (0.22, 0.40) | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.22, 0.39) | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.47, 2.99) | <0.001 |

| Minority non-MSM | 0.37 (0.30, 0.45) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.30, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.48, 0.78) | <0.001 |

| Not a current drinker (reference group) | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | ||

| non-Hazardous | 1.06 (0.90, 1.25) | 0.48 | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | 0.55 | ||

| Hazardous/Binge | 1.37 (1.16, 1.63) | 0.0002 | 1.53 (1.26, 1.87) | <0.001 | ||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 1.24 (0.99, 1.56) | 0.07 | 1.06 (0.82, 1.37) | 0.67 | ||

| Drug abuse/dependence | 0.88 (0.74, 1.06) | 0.18 | 1.05 (0.84, 1.31) | 0.67 | ||

| HIV-infection | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) | <0.001 | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 1.05 (0.89, 1.24) | 0.58 | ||||

| Age (10 year increments) | 1.04 (0.95, 1.13) | 0.38 | ||||

| Major Depression | 1.06 (0.83, 1.35) | 0.63 | ||||

| Homelessness | 1.17 (0.99, 1.37) | 0.06 | ||||

| Married (reference group) | 1 | n/a | ||||

| Divorce | 0.35 (0.29, 0.43) | <0.001 | ||||

| Separated | 0.39 (0.30, 0.51) | <0.001 | ||||

| Widowed | 0.29 (0.19, 0.45) | <0.001 | ||||

| Never married | 0.32 (0.25, 0.39) | <0.001 | ||||

| Living with a partner | 0.75 (0.56, 0.98) | 0.04 | ||||

| Income≥$12,000 US | 1.14 (0.98, 1.34) | 0.10 | ||||

Model adjusted for alcohol & drug abuse

Adjusted for other covariates of interest (HIV, Hepatitis C, depression, age, homelessness, relationship status, and income)

In a sub-analysis looking at the interaction between MSM and minority status (data not shown), for three of the risk factors (being under the influence during sex, detectable HIV viral load, and non-condom use) the interaction terms between minority and MSM status were not significant, suggesting a purely additive association. For multiple sexual partners the interaction was significant (p=0.001) and negative (OR: 0.49; 95% CI 0.32, 0.74). Minority and MSM were not additive in their effects.

Discussion

In a large sample of HIV-infected, and demographically and behaviorally similar uninfected participants, we found minority MSM were significantly more likely to have risk factors (except non-condom use) - multiple sexual partners, being under the influence of drugs or alcohol during sex, and having a detectable HIV viral load. Both substance use and relationship status appear to attenuate this association.

In unadjusted models, minority MSM had the highest odds for 3 of the 4 risk factors. The crude odds of multiple partners for minority MSM status was 10 times the crude odds for non-MSM whites, and remained significant, though diminished, in the adjusted model. It is not clear how to interpret relationship status, a potential mediator in this association. However, studies have shown an association between relationship status and risk factors. Being married was associated with reduced odds of multiple partners, substance use, HIV suppression, and less condom use. (15, 25–27) While it is safe to assume being married at the time of data collection meant being married to a woman, we cannot assume that being married precludes a man having sex with men.(28) Seven percent of MSM in our sample reported being married. Substance use on the other hand is well established as a contributing factor to risk behaviors and a prevalent factor among minorities and MSM. More important, it is a modifiable factor that can be incorporated into treatment efforts to reduce risk.

It is of great concern that the minority MSM group was the strongest factor associated with multiple partners. Rosenberg and colleague found that black MSM have a lower threshold than whites for the number of sexual partners needed for a 50% chance of acquiring HIV.(29) Blacks who had 3 sexual partners, compared to 7 partners (more than twice as many) for whites, were more likely to acquire HIV.(29)

Also concerning is their association with sex under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol. HIV-infected minorities, regardless of MSM status, had a higher prevalence of substance use compared to the other groups (data not shown). Pandrea and colleagues, as well as Baliunas and colleagues, have demonstrated that alcohol is a major contributing factor in HIV transmission and progression.(30,31) In a recent paper by Mayer and colleagues, they showed that heavy alcohol use and stimulant drugs use were associated with enhanced HIV transmission among MSM in care.(32)

In this study, HIV-infected participants had low adherence to antiretroviral medications, high viral load, and a high prevalence of risk factors. The low adherence coupled with high viral load and high prevalence of risk factors, is a potential mode of transmission, especially among minorities. While interracial or interethnic dating and marriage has increased over the past decade according the 2010 US census data,(23) for a large percent of the US population, socialization and coupling is still within race/ethnic groups. Thus, if uninfected minority MSM with unhealthy alcohol (i.e. hazardous/binge drinking and/or alcohol abuse/dependence) and drug use, and HIV-infected minorities with increased risk of HIV transmission are engaging in sexual risk behavior together, this may contribute to the consistently high rates of new HIV cases among this population. Upon closer examination, we found that among minority MSM, those who reported multiple partners, versus not, were substantially more likely to have unhealthy alcohol use (54% vs. 37%). The implication of a combination of risk on HIV acquisition and transmission is troubling.

Of note, risk of transmission is dependent on prevalence of HIV in the sex network, not just the individual risk behavior (e.g. non-condom use); and it is well established that minority populations have a higher prevalence of HIV infection compared to white populations.(1) In addition, Edelman and colleagues found among a group of sexually active study participants, black and MSM status was significantly associated with incomplete partner notification,(33) which may leave their sexual network unaware of their HIV status and risk. This combination of multiple partners, being under the influence (which may impair condom use), lower threshold for the number of sexual partners needed for transmission, delayed diagnosis and lower HIV awareness (4, 34–37), and poor partner notification, are prime conditions for HIV transmission and acquisition; putting minority MSM at greater likelihood of contracting HIV. Targeting individual risk factors may not be enough for minorities at risk.(38) Studies have indicated that social network interventions are needed. Interventions at the individual level have not been as effective in reducing HIV transmission in minority populations as in white populations.(39, 40)

Research on the combined effect of HIV risk (i.e. multiple partners, sex under the influence, detectable HIV viral load, and non-condom use) on HIV transmission and acquisition is scant. However, it is plausible to suspect that having two or more sexual risk behaviors has an additive effect on HIV transmission. For example, a person who is under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol during sex is less likely to use a condom (41–43), or if they did use a condom, it is possible that it was not used properly.(20,45) Drugs and/or alcohol impair physical function and application of condom may be subpar, rendering it less effective. Macaluso and colleagues examined factors associated with condom failure and found risky behavior, defined as having sex for money or drugs and having sex under the influence (i.e. while drunk or high on drugs), to be the strongest determinant of condom failure (OR: 2.00; 95% CI 1.40, 2.80, p=0.0003).(20). Thus, the strong association between minority MSM and sex under the influence is troubling even in the presence of reported condom use. In their Comparison of HIV Prevention Interventions, using a jurisdiction-specific operations research model of HIV prevention in New York City, Kessler and colleagues examined different combination of prevention strategies, some of which included condom use, addressing unhealthy alcohol use and drug use, and it suggested risk behaviors could be additive in their effect.(46) More studies on the combined effect of risky behaviors in high risk sub populations, such as minority MSM, are needed.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations. Some variables were self-reported, which can give rise to non-differential misclassification (from either over reporting or underreporting), which biases towards a null finding. Since our findings were significant despite this limitation, it is possible that the association could be stronger than what we found. Also, mediation was not an a priori hypothesis, and it is difficult to fully assess mediators in a cross-sectional study, but a decrease when substance use and relationship status were added to the model was observed, which warrants further examination of suspected partial mediation.(47) Future studies are needed to explore this finding. Finally, our conclusions are based on cross-sectional data, which does not afford directional and causal inferences.

However, this study has several strengths. It is a large and diverse sample, with multiple sites around the US, and included measures of important factors, including HIV viral load. We were also able to evaluate an under-examined high-risk group, minority MSM, as well as increasing levels of alcohol use.

Conclusion

These analyses suggest that minority MSM would be more likely to have multiple sexual partners and more likely to have sex under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol, making minority MSM a subgroup with a higher prevalence of factors associated with HIV transmission risk. Moreover, co-occurrence of risk factors indicates that those with detectable viral load were more likely to report multiple sex partners and sex under the influence of alcohol and/or drugs. Our data support the need for tailored prevention and treatment efforts geared towards these behaviors among minority MSM to help abate new HIV cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Scott Braithwaite for input on multiple risk behaviors and helpful comments on this paper. We would also like to acknowledge the Veterans who participate in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) and the study coordinators and staff at each VACS site and at the West Haven Coordinating Center.

Funding: This study was funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number U10 AA013566, U24 AA020794, and U01 AA020790).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosures: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.New HIV Infections in the United States. [Accessed March 12, 2012];2014 May 29; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/basic.htm#hivest.

- 2.Oramasionwu CU, Brown CM, Ryan L, Lawson KA, Hunter JM, Frei CR. HIV/AIDS disparities: the mounting epidemic plaguing US blacks. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009 Dec 1;101(12):1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. [Accessed March 12, 2012];HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012 :17. (No. 4). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/#supplemental.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Disparities in Diagnoses of HIV Infection Between Blacks/African Americans and Other Racial/Ethnic Populations --- 37 States, 2005--2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Feb 4;60(04):93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia J, Parker RG, Parker C, Wilson PA, Philbin M, Hirsch JS. The limitations of ‘Black MSM’ as a category: Why gender, sexuality, and desire still matter for social and biomedical HIV prevention methods. Global public health. 2016 Jan;28:1–23. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1134616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STDs, and TB. [Accessed February /25, 2016]; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/

- 7.Jeffries WL, 4th, Marks G, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Millett GA. Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013 May;17(4):1442–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood JE, Friedman AL. Unveiling the hidden epidemic: a review of stigma associated with sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2011 Jun;8(2):159–170. doi: 10.1071/SH10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005 Aug 1;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. [Published Accessed June 25, 2012];Condom Fact Sheet In Brief. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/brief.html.

- 11.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, et al. Specific Sex-Drug Combinations Contribute to the Majority of Recent HIV Seroconversions Among MSM in the MACS. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;51(3):349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanable PA, McKirnan DJ, Buchbinder SP, et al. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among men who have sex with men: the effects of consumption level and partner type. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):525–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute on Drug Abuse Commonly Abused Drugs. [Accessed June 25, 2016]; Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/commonly-abused-drugs-charts.

- 14.Calsyn DA, Cousins SJ, Hatch-Maillette MA, et al. Sex Under the Influence of Drugs or Alcohol: Common for Men in Substance Abuse Treatment and Associated with High Risk Sexual Behavior. The American journal on addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2010;19(2):119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS. Multiple sexual partners among US adolescents and young adults. Family planning perspectives. 1998 Nov 1;:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Justice AC, Dombrowski E, Conigliaro J, et al. Veterans’ Aging Cohort Study (VACS): Overview and description. Medical Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S13. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223741.02074.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitz R. Clinical Practice: Unhealthy Alcohol Use. N Engl J Med. 2005 Feb 10;352(6):596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Grasso C, et al. Substance Use Among HIV-Infected Participants Engaged in Primary Care in the United States: Findings From the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems Cohort. American Journal of Public Health. 2013 Aug;103(8):1457–1467. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCance-Katz EF, Lum PJ, Beatty G, Gruber VA, Peters M, Rainey PM. Untreated HIV Infection is Associated with Higher Blood Alcohol Levels. J Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012 Jul 1;60(3):282–288. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318256625f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macaluso M, Kelaghan J, Artz L, Austin H, Fleenor M, Hook EW, III, Valappil T. Mechanical failure of the latex condom in a cohort of women at high STD risk. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1999 Sep 1;26(8):450–458. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCance-Katz EF, Gruber VA, Beatty G, Lum PJ, Rainey PM. Interactions between Alcohol and the Antiretroviral Medications Ritonavir or Efavirenz. J Addict Med. 2013 Jul-Aug;7(4):264–270. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318293655a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998 Sep 14;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census. [Accessed February 15, 2013]; Available at: http://www.census.gov/

- 24.Braithwaite RS, Kozal MJ, Chang CC, et al. Adherence, virological and immunological outcomes for HIV-infected veterans starting combination antiretroviral therapies. AIDS. 2007 Jul 31;21(12):1579–1589. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281532b31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merline AC, O’malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 2004 Jan;94(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, et al. Viral Suppression and Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among Alcohol Using HIV Positive Adults. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2014;21(5):811–820. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Condom use rates in a national probability sample of males and females ages 14 to 94 in the United States. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010 Oct 1;s7(5):266–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins Daryl J. “Gay men from heterosexual marriages: Attitudes, behaviors, childhood experiences, and reasons for marriage”. Journal of homosexuality. 2002 Jul 31;42(4):15–34. doi: 10.1300/J082v42n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg E, Kelley C, O’Hara B, Frew P, Peterson J, Sanchez T, del Rio C, Sullivan P. Equal behaviors, unequal risks: the role of partner transmission potential in racial HIV disparities among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US; Washington DC. International AIDS Conference.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandrea I, Happel KI, Amedee AM, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Alcohol’s Role in HIV. Transmission and Disease. Progression. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010 Sep 22;33(3):203–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayer KH, Skeer MR, O’Cleirigh C, Goshe BM, Safren SA. Factors Associated with Amplified HIV Transmission Behavior among American Men who have Sex with Men Engaged in Care: Implications for Clinical Providers. Ann Behav Med. 2014 Apr;47(2):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelman EJ1, Gordon KS, Hogben M, Crystal S, Bryant K, Justice AC, Fiellin DA. Sexual partner notification of HIV infection among a National United States-based sample of HIV-infected men. AIDS Behav. 2014 Oct;18(10):1898–1903. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0799-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson KM, Thiede H, Hawes SE, Golden MR, Hutcheson R, Carey JW, Kurth A, Jenkins RA. Why the Wait? Delayed HIV Diagnosis among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Journal of Urban Health. 2010 Jul;87(4):642–655. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9434-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance. [Accessed February 15, 2013];2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats10.

- 36.Wejnert C, Le B, Rose CE, Oster AM, Smith AJ, Zhu J Gabriela Paz-Bailey for the NHBS Study Group. HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men-20 cities, United States, 2008 and 2011. PLoS One. 2013 Oct 23;8(10):e76878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV prevalence, unrecognized infection, and HIV testing among men who have sex with men—five US cities, June 2004-April 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005 Jun 25;54(24):597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and Drug Behavior Patterns and HIV and STD Racial Disparities: The Need for New Directions. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnus M, Kuo I, Phillips G, Shelley K, Rawls A, Montanez L, et al. Elevated HIV prevalence despite lower rates of sexual risk behaviors among black men in the District of Columbia who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(10):615–622. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and substance use in the United States. [Accessed August 12, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/riskbehaviors/substanceuese.html.

- 42.Sanchez ZM, Nappo SA, Cruz JI, Carlini EA, Carlini CM, Martins SS. Sexual behavior among high school students in Brazil: alcohol consumption and legal and illegal drug use associated with unprotected sex. Clinics. 2013;68(4):489–494. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(04)09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen VC, Jr, Myers HF, Ray L. The Association Between Alcohol Consumption and Condom Use: Considering Correlates of HIV Risk Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior. 2015 Sep 1;19(9):1689–1700. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macaluso M, Kelaghan J, Artz L, Austin H, Fleenor M, Hook EW, III, Valappil T. Mechanical failure of the latex condom in a cohort of women at high STD risk. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1999 Sep 1;26(8):450–458. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone E, Heagerty P, Vittinghoff E, Douglas JM, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Celum CL, Gross M, Woody GE, Marmor M, Seage GR. Correlates of condom failure in a sexually active cohort of men who have sex with men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1999 Apr 15;20(5):495–501. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler J, Myers JE, Nucifora KA, et al. Averting HIV Infections in New York City: A Modeling Approach Estimating the Future Impact of Additional Behavioral and Biomedical HIV Prevention Strategies. PLoS ONE. 2013 Sep 13;8(9):e73269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986 Dec;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]