Abstract

Purpose

Brain Angiogenesis Inhibitor (BAI1) facilitates phagocytosis, and bacterial pathogen clearance by macrophages; however, its role in viral infections is unknown. Here we examined the role of BAI1, and its N-terminal cleavage fragment (Vstat120) in antiviral macrophage responses to oncolytic herpes simplex virus (oHSV).

Experimental Design

Changes in infiltration and activation of monocytic and microglial cells after treatment of glioma-bearing mice brains with a control (rHSVQ1) or Vstat120-expressing (RAMBO) oHSV was analyzed using flow cytometry. Co-culture of infected glioma cells with macrophages or microglia was used to examine antiviral signaling. Cytokine array gene expression and ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) helped evaluate changes in macrophage signaling in response to viral infection. TNFα blocking antibodies and macrophages derived from Bai1−/− mice were used.

Results

RAMBO treatment of mice reduced recruitment and activation of macrophages/microglia in mice with brain tumors, and showed increased virus replication compared to rHSVQ1. Cytokine gene expression array revealed that RAMBO significantly altered the macrophage inflammatory response to infected glioma cells via altered secretion of TNFα. Further we showed that BAI1 mediated macrophage TNFα induction in response to oHSV therapy. Intracranial inoculation of wild type/RAMBO virus in Bai1−/− or wild type non-tumor-bearing mice revealed the safety of this approach.

Conclusions

We have uncovered a new role for BAI1 in facilitating macrophage anti-viral responses. We show that arming oHSV with antiangiogenic Vstat120 also shields them from inflammatory macrophage antiviral response, without reducing safety.

Keywords: TNFα, macrophage, microglia, innate immune responses, oncolytic virus, HSV-1, BAI1, Vasculostatin-120 (Vstat120), adhesion GPCR

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary malignant brain tumor, with a median survival of less than 15 months from diagnosis (1). Current standard of care combines surgical resection, with radiation and chemotherapy, but even with this aggressive first line of therapy, most patients relapse with refractive and resistant disease (2). Five year survival for adults (>40 years) remains less than 10%. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutics to fight this disease. HSV-1-derived oncolytic viruses (oHSV) are one such novel promising therapeutic strategy, which utilize genetically modified viruses to exploit weakened protein kinase R (PKR) response in malignant cells, to specifically replicate and destroy tumors (3). First-generation attenuated viruses have proven safe in clinical trials, and have paved the way for second generation armed viruses that can deliver a therapeutic payload to the tumor microenvironment (4). T-Vec (tamilogenelaherpavec; IMLYGIC®) is an attenuated second-generation oHSV that encodes GM-CSF, and was recently approved for use in unresectable metastatic melanoma (5).

We have recently described the generation and anti-tumor efficacy of an oHSV expressing antiangiogenic Vstat120, called RAMBO (Rapid Antiangiogenisis Mediated by Oncolytic Virus) (6). Vstat120 is the extracellular fragment of Brain Angiogenesis Inhibitor 1 (BAI1/ADGRB1), an adhesion G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) primarily expressed in the brain. The expression of this protein is reduced in several solid tumors including GBM, colorectal cancer, pulmonary adenocarcinoma, and others, suggesting its loss may be of significance in tumor progression or growth (7–11). Consistent with this, Vstat120 binds to CD36 on endothelial cells, leading to their apoptosis (12). The potent antiangiogenic effects of Vstat120 result in reduced tumor growth and angiogenesis in several preclinical studies when tumor cells over-express it (13).

Apart from astrocytes and neurons, BAI1 is also expressed on macrophages and microglia (14–16), where it mediates a variety of functions including phagocytosis, and clearance of apoptotic cells via its ability to recognize phosphatidylserine (14, 16, 17). As a pattern recognition receptor, its expression on macrophages is important for the identification of Gram-negative bacteria through their surface lipopolysaccharides, and activation of pro-inflammatory immune responses (18). The anti-angiogenic and phagocytic functions of BAI1 involve the five thrombospondin type I repeats (TSRs) present on the extracellular domain of the receptor (14, 18), thus implying that Vstat120 might modulate this function. The role of BAI1 or Vstat120 in orchestrating antiviral macrophage innate responses has not been previously investigated.

Macrophages mediate an innate immune response against viral infection that antagonizes oHSV replication. This response is thought to be one of the major factors that limits virus spread, and reduces tumor destruction through direct viral oncolysis (19–22). Macrophages can directly uptake viruses through endocytosis, or reduce viral replication through secretion of antiviral cytokines (22, 23). Several studies have shown that blocking microglia and infiltrating macrophages can significantly increase oHSV therapeutic efficacy, and these strategies may be translatable to patients (24–29). Given the role of BAI1 in phagocytosis and bacterial clearance, we hypothesize that it might choreograph an antiviral defense response in macrophages, and that Vstat120 its soluble extracellular fragment could interfere with this function.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

LN229, X12v2, U87ΔEGFR, and U251-T2 human glioma cell lines and Vero cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). U251-T2/T3 were created by serially passaging U251MG cells in mice two or three times, respectively. Monkey kidney epithelial-derived Vero cells and U87ΔEGFR human glioma cells were obtained from E. A. Chiocca (Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio). X12v2 cells were obtained from Mayo Clinic, and maintained as tumor spheres in Neurobasal Medium supplemented with 2% B27, human EGF (50 ng/ml), and bFGF (50 ng/ml) in low-attachment cell culture flasks as previously described (30). Murine BV2 microglia were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. Murine RAW264.7 macrophages were received from S. Tridandapani (Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio), and were grown in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. All human cells are routinely authenticated, through the University of Arizona Genetics Core via STR profiling, and maintained below passage 50 after STRS profiling. All cells are routinely monitored for changes in morphology and growth rate. All cells are routinely tested for mycoplasma. All cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% carbon dioxide, and maintained with 100 units/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin.

Viruses and virus replication assay

Genetic composition of rHSVQ1 and RAMBO viruses were previously described (6, 31), and their titers determined on Vero cells via a standard plaque forming unit (PFU) assay (32).

Co-culture Assays

Glioma cells were infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 or 2 as indicated in DMEM supplemented with 0.05% FBS for one hour and then washed with PBS to remove unbound virus. Infected cells were then overlaid with microglia or macrophages (at 2:1 ratio of macrophages/microglia to glioma cells) for 12 hours; samples were collected pre-virus burst. For TNFα blocking antibody assays, 1800 ng/ml of mouse TNFα neutralizing antibody [D2H4; Cell Signaling] or an isotype control were utilized.

Isolation of tumor-associated brain microglia and macrophages

Microglia and macrophage populations were isolated for flow cytometry analysis from murine brain homogenates as previously described (22). Briefly, the tumor-bearing hemispheres of mice brains were dissected, and microglia/macrophage populations were collected via Percoll isolation from the interphase between the 70% and 50% Percoll gradient layers.

Primary Murine Bone Marrow-derived Macrophage Generation

Bai1+/− heterozygote breeding pairs were bred, and wild type and knock out mice identified by PCR as described (33). Bone marrow derived macrophages were isolated as previously described (34). Briefly, the tibia and femurs of euthanized mice were flushed with PBS several times to remove bone marrow cells. Cells were centrifuged and plated in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep. 20 ng/mL murine macrophage colony stimulating factor (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 10 ug/mL of polymyxin B (Calbiochem/EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) were added to the cultures. Cells were allowed to mature for 8 days prior to use.

Microglia and macrophage antibody staining

Staining of surface antigens were performed as previously described (35, 36). Briefly, Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Cells were then incubated with the appropriate antibodies: CD45, CD11b, MHCII, CD86, LY6C, and CD206 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 45 minutes. Cells were re-suspended in FACS buffer (2% FBS in HBSS with 1 mg/ml sodium azide) for analysis. Non-specific binding was assessed via isotype-matched antibodies. Antigen expression was determined using a Becton-Dickinson FACS Caliber four-color cytometer. Ten thousand events were recorded for each sample and isotype matched-conjugate. Data was analyzed using FlowJo software (FloJo, LLC, Ashland, OR).

Animal surgery

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care of The Ohio State University guidelines, and were approved by the institutional review board. Intracranial surgeries were performed as previously described with stereotactic implantation of 100,000 U87ΔEGFR in nude mice (32). Tumors were treated with HBSS/PBS, rHSVQ1, or RAMBO virus (1x105 PFU/mouse) at the location of tumor implantation. Tumor-bearing hemispheres were collected by gross dissection 3 days after treatment, or as indicated. For safety studies, we used female BALB/C mice (~6 weeks of age) or Bai1 wildtype or knockout C57/Bl/6 mice (male and female littermates) (33). Virus (F strain or RAMBO) was injected into naive brains at indicated doses. Weight recorded to the nearest gram; mice were euthanized upon reaching early removal criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparision post hoc tests, or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons were used to analyze changes in cell killing, viral plaque forming assays, gene expression, and flow cytometry assays. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Graph Pad Prism software [version 5.01] or by a biostatistician. A p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Derived p values are identified as *, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001. For the cytokine gene expression analysis, CT scores were processed and analyzed by QIAGEN web portal directly (Qiagen/SABiosciences, Valencia, CA; GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center). Differentially expressed genes were selected by a fold change greater than 1.5 and p value less than 0.05.

Results

Impact of RAMBO on infiltration and activation of macrophages and microglia in intracranial tumors

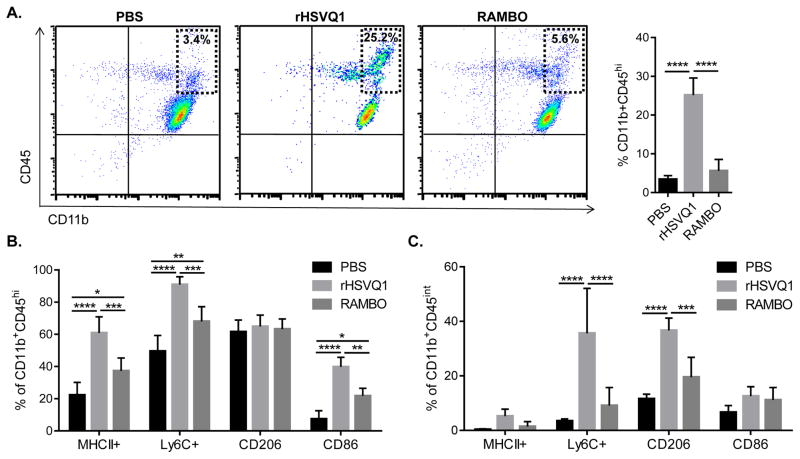

To examine the effect of macrophage/microglia responses to oHSV infection with or without Vstat120, we treated mice with established intracranial gliomas with PBS, rHSVQ1 (control oHSV) or RAMBO (oHSV-expressing Vstat120). Three days after treatment, we analyzed tumor-bearing hemispheres for infiltrating monocytic macrophages (CD11bhi/CD45hi) and microglia (CD11b+/CD45int) cells by flow cytometry. Consistent with previous studies (22), rHSVQ1 infection resulted in a significant increase in macrophage infiltration, compared to PBS injection control (PBS, 3.41% vs. rHSVQ1, 25.17%; p≤0.001; Figure 1A). Interestingly, RAMBO treatment resulted in a significant reduction in virus-induced macrophage infiltration, compared to rHSVQ1 (rHSVQ1, 25.17% vs. RAMBO, 5.60%; p≤0.001; Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Effect of RAMBO on macrophage and microglial response to oHSV therapy.

Mice bearing intracranial U877Delta;EGFR tumors treated with PBS, rHSVQ1 or RAMBO were sacrificed three days after treatment, and tumor-bearing hemispheres were analyzed for macrophage or microglia infiltration and activation by flow cytometry. (A) Left, representative scatter plots showing CD11b+/CD45+ cells isolated from tumor-bearing hemispheres from mice. Dashed box, indicates CD11bhiCD45hi infiltrating monocytic macrophages. Right panel represents mean percentage of CD11bhiCD45hi of population from three independent experiments (mean ± s.d). (B) Percentage of CD11bhiCD45hi cells (infiltrating monocytic macrophages) staining positive for activation markers MHCII, Ly6C, CD206, and CD86. (C) Percentage of CD11b+CD45int cells (microglia) staining positive for activation markers MHCII, Ly6C, CD206, and CD86. (*, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001)

To further evaluate the activation status of the tumor-infiltrating macrophages, we stained them for antigen-presenting molecule MHCII, activation marker Ly6c, pattern recognition receptor CD206, and T cell costimulatory signal CD86. As previously reported, rHSVQ1 treatment increased expression of activation markers on macrophages and microglia (Figure 1B,C; light grey bars) (22). Surprisingly, we saw a reduction in expression of activation markers on both infiltrating macrophages and resident microglia in RAMBO-treated tumors (Figure 1B,C; dark grey bars). Combined, these data show that RAMBO infection is associated with dramatically reduced macrophage infiltration, and that these cells are in a lower immune activation state. To address the generalizability of these results, we performed a similar experiment using the murine model of Ewing sarcoma. Subcutaneous tumors were treated with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO, and tumor tissue was collected 3 days after virus treatment. Using immunohistochemistry of tumor sections, we stained the tumors for CD68+ve cells, indicative of macrophages (Supplementary Figure 1). Similar to results described above (Figure 1), we found a robust decrease in macrophages in RAMBO-treated tumors (Supplementary Figure 1, brown staining).

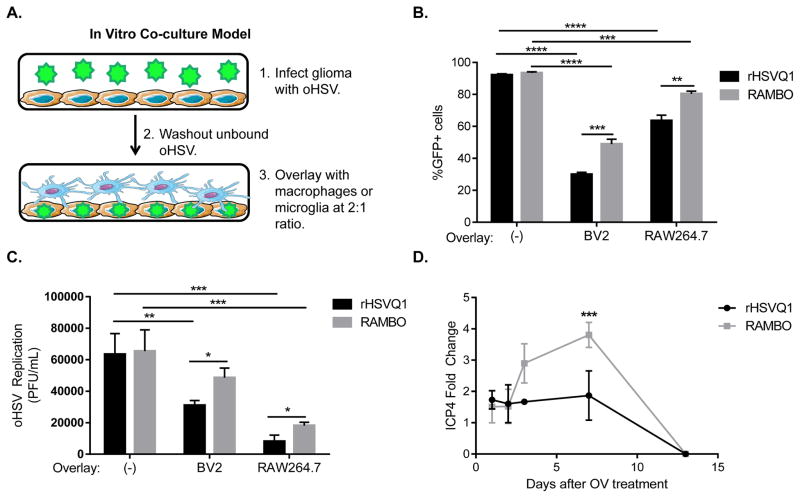

Impact of RAMBO on macrophage and microglial responses to oHSV

Since both macrophages and microglia are implicated in oncolytic virus clearance (22), we compared the effect of macrophages and microglia on rHSVQ1 or RAMBO replication in an in vitro co-culture model. Human glioma cells infected with GFP-expressing oHSV were overlaid with murine microglia (BV2) or macrophages (RAW264.7) (schematic in Figure 2A). In the absence of macrophages or microglia, rHSVQ1 and RAMBO infected and replicated in glioma cells equally (Figure 2B,C; (−), no overlay), and did not have productive replication in either macrophages or microglia alone (not shown). Flow cytometry analysis of tumor cells infected with GFP-expressing rHSVQ1 revealed a reduction in fluorescent cells in the presence of either BV2 or RAW cells (Figure 2B, black bars). The number of GFP positive (GFP+) glioma cells infected with RAMBO was higher than that obtained with rHSVQ1 in the presence of macrophages, as well as microglia (Figure 2B, black bars [rHSVQ1] vs. grey bars [RAMBO]). Consistent with a reduction in infected tumor cells, addition of microglia or macrophages reduced the replication of both viruses, albeit to a lesser extent for RAMBO (Figure 2C, black bars [rHSVQ1] vs. grey bars [RAMBO]). Additionally Vstat120 expression by glioma cells cultured with HSVQ1 infected glioma cells did not affect virus replication. Co-culture of Vstat120-expressing glioma cells with rHSVQ1-infected glioma prior to overlay with macrophages rescued virus replication inhibition by macrophages (Supplementary Figure 2B, right panel [control glioma overlay] vs. left panel [Vstat120-expressing glioma overlay]).. Together these findings show that macrophages/microglia suppress HSV-1 infection and replication in glioma cells in culture, and that the presence of Vstat120 in the secreted ECM rescues the effect of macrophage/microglia mediated inhibition of OV replication.

Figure 2. Effect of macrophage and microglial cells on oHSV replication.

(A) Schematic of experimental design used: U251 glioma cells (brown) were infected with oHSV (rHSVQ1 or RAMBO; green) for an hour before unbound virus was washed away. Macrophages (RAW 264.7) or microglia (BV2) represented in blue were then overlaid onto infected tumor cells, at a 2:1 ratio. (B) Changes in percentage of GFP+ infected tumor cells in the presence or absence of macrophage (RAW 264.7) or microglia (BV2) was measured by flow cytometry 12 hours after infection with the indicated virus. Data shown are mean percentage of GFP+ tumor cells (± s.d) upon infection with the indicated virus (n=3 samples/group) (C) Changes in oHSV replication from infected tumor cells in the presence or absence of RAW or BV2 cells 12 hours after infection was measured by a standard plaque assay. Data shown is mean plaque-forming units/mL ± s.d. (D) Mice bearing intracranial U87ΔEGFR tumors treated with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO were sacrificed at indicated time points after treatment, and tumor-bearing hemispheres were analyzed for viral ICP4 gene expression. (*, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001)

To evaluate the in vivo significance of these results, we treated mice bearing established intracranial glioma with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO. At indicated time points after virus treatment, we measured viral ICP4 gene expression from tumor-bearing hemispheres (Figure 2D). The peak of viral transgene expression occurred 7 days after oHSV treatment. At this time point, and over time, RAMBO showed significantly more replication in murine glioma, as compared to rHSVQ1 (rHSVQ1, 1.9-fold increase in ICP4 gene expression on Day 7 over baseline; RAMBO, 3.8-fold increase over baseline [p≤0.001]).

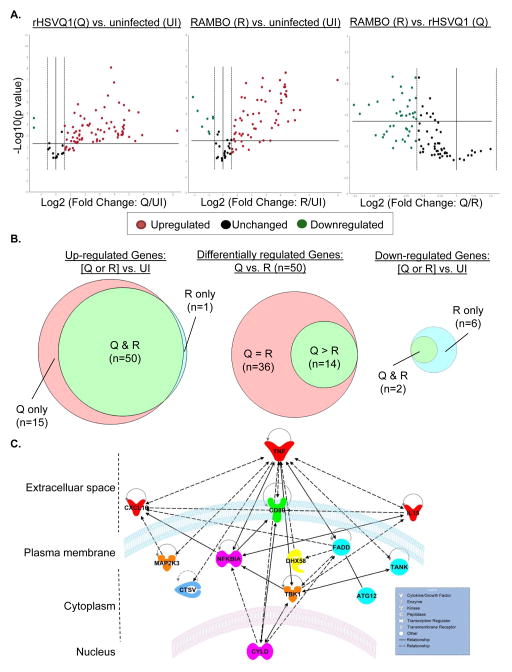

Reduced anti-viral immune response from macrophages in response to RAMBO infection in glioma cells

The above results suggested that RAMBO could reduce macrophage antiviral signaling. To probe for changes in anti-viral immune signaling in macrophages, we used a mouse species-specific anti-viral gene expression RT-PCR array to tease out changes in macrophage transcripts when exposed to control or virally-infected glioma cells in a co-culture system. Genes altered by >1.5 fold were considered changed. Volcano plots evidenced a clear induction of 65 out of the 84 antiviral genes represented on the array in macrophages co-cultured with rHSVQ1-infected human glioma cells (Figure 3A,B; left panel; Supplementary Table 1). Only 50 of these 65 cytokine genes were upregulated in macrophages cultured with RAMBO infected glioma cells (Figure 3A,B; middle panel; Supplementary Table 1). Comparison of the level of induction of these 50 mRNAs under either rHSVQ1 vs. RAMBO infected cell culture conditions, evidenced that 14 showed higher induction (>1.5 fold more) in the rHSVQ1 infected co-culture (Figure 3A,B; Supplementary Table 2). We then used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Figure 3C), a software that uses algorithms to build networks based on the functional and biological connectivity of genes, to examine for connectivity between these 14 cytokines, and found convergence on canonical pathways associated with TNF receptor signaling (Figure 3C). From this analysis, TNFα emerged as a major signaling node negatively regulated by RAMBO.

Figure 3. Changes in anti-viral signaling in macrophages co-cultured with glioma infected with RAMBO Vs rHSVQ1.

Comparison of murine macrophage anti-viral gene signaling when cultured with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO-infected glioma cells. Briefly, U251 human glioma cells infected with PBS, rHSVQ1 or RAMBO were overlaid with murine RAW macrophage cells. 12 hours post infection, we analyzed changes in murine specific cytokine gene expression using an antiviral gene expression PCR array. (A) Volcano plot comparing normalized changes in gene expression of macrophages cultured with glioma cells treated with rHSVQ1 vs. uninfected (left panel), RAMBO vs. uninfected (middle panel), and RAMBO vs. rHSVQ1 (right panel) using 1.5-fold gene change as cut-off, and p≤0.05. (B) Venn diagrams of macrophage genes induced upon infection with rHSVQ1 and/or RAMBO (left panel), induced by both rHSVQ1 and RAMBO relative to uninfected (middle panel) and down regulated by rHSVQ1 and/or RAMBO (right panel). (C) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of genes showing a differentially induction (≥ 1.5 fold) in macrophages in response to rHSVQ1 vs. RAMBO infected cells. The network is graphically-represented as nodes (genes); bold lines connecting the nodes indicate direct interaction, while the dashed lines suggest indirect interaction

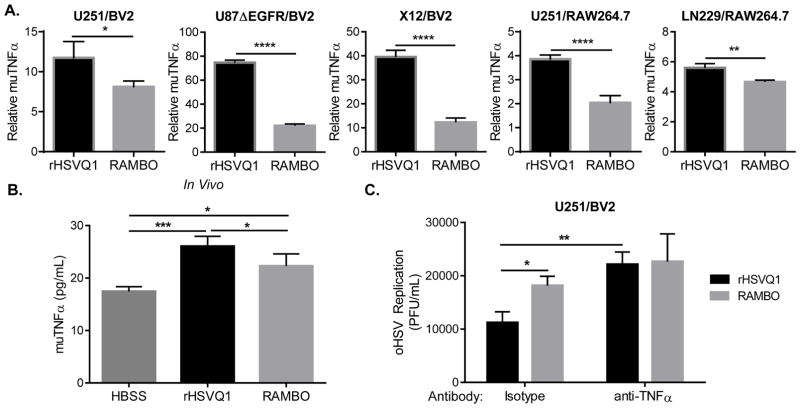

Reduced TNFα production from macrophages and microglia in response to RAMBO-infected tumor cells

To validate the IPA network prediction, we examined changes in TNFα gene expression by macrophages or microglia after co-culture with multiple different human glioma cell lines infected with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO. Briefly, the indicated human glioma cells were infected with either rHSVQ1 or RAMBO and then overlaid with murine microglia (BV2) or murine macrophages (RAW264.7). Changes in macrophage/microglia TNFα gene expression relative to uninfected cultures was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR using species-specific primers. Consistent with the cytokine array profile, macrophages and microglia cultured with RAMBO-infected glioma cells showed a significantly reduced induction of TNFα, compared to rHSVQ1 co-culture (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. RAMBO reduces infection induced TNFα secretion by macrophages and microglia.

(A) Human glioma cells infected ± oHSV (rHSVQ1 or RAMBO) were overlaid with murine macrophages or microglia. Change in murine TNFα gene expression relative to uninfected c0-cultures was measured twelve hours after overlay of the indicated RAW or BV2 cells (using species-specific primers). Data shown is mean fold-change in gene expression ± s.d., normalized to expression without infection (Relative expression, normalized to uninfected control; 2−ΔΔCt). (B) Mice bearing intracranial U87ΔEGFR tumors treated with HBSS (inoculation control), rHSVQ1, or RAMBO were sacrificed 3 days after treatment, and tumor-bearing hemispheres were analyzed for muTNFα using ELISA. Data shown is mean muTNFα (pg/mL) ± s.d. rHSVQ1 infection resulted in significant increase in muTNFα, compared to uninfected injection control (HBSS). (D) U251 glioma cells infected with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO were overlaid with BV2 microglia with/without isotype or TNFα-blocking antibody. 12 hours later, virus replication was evaluated via standard plaque assay. Data shown is mean replication (plaque-forming units/mL) ± s.d. (*, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ***, p≤0.001; ****, p≤0.0001)

To evaluate the in vivo significance of these results, we compared TNFα secretion in mice bearing intracranial tumors treated with rHSVQ1 or RAMBO. Briefly, mice bearing intracranial tumors were treated with the indicated virus seven days after tumor cell implantation. Three days after treatment, mice were sacrificed and tumor-bearing hemispheres were harvested and lysed. Figure 4B shows a significant increase in murine TNFα after rHSVQ1 treatment, compared to untreated controls (p≤0.001), and a significantly less robust expression with RAMBO treatment relative to rHSVQ1 treatment (p≤0.05).

Effect of TNFα blockage on microglial response to oHSV

Collectively, our results show that increased replication of RAMBO in vivo correlates with: 1) reduced macrophage/microglial infiltration; 2) reduced macrophage/microglial activation; and 3) reduced TNFα production in response to infected tumor cells. TNFα is a pleiotropic cytokine upregulated in response to CNS infections and we have previously shown that it plays a key role in blocking oHSV efficacy (22). To determine whether induction of TNFα in macrophage/microglial cells plays a causal role in the differential viral replication efficacy in the co-culture system, we compared rHSVQ1 and RAMBO replication efficacy in the presence or absence of TNFα blocking antibody. As already observed above, RAMBO was less sensitive to microglia- and macrophage-mediated inhibition of viral replication compared to rHSVQ1 (Figure 2B,C). However, in the presence of a TNFα blocking antibody, rHSVQ1 replicated as well as RAMBO in glioma cells cultured with BV2 (Figure 4C). These data suggest that oHSV-infected glioma cells induce murine TNF production by macrophage/microglia, which then suppresses oHSV replication through a paracrine mechanism. The strength of the TNFα response elicited by each virus correlates with its differential viral replication; this explains why RAMBO replicates better than rHSVQ1 in the co-culture system. These findings further suggest that Vstat120 expression by RAMBO-infected glioma cells prevents TNFα production by macrophages/microglial cells.

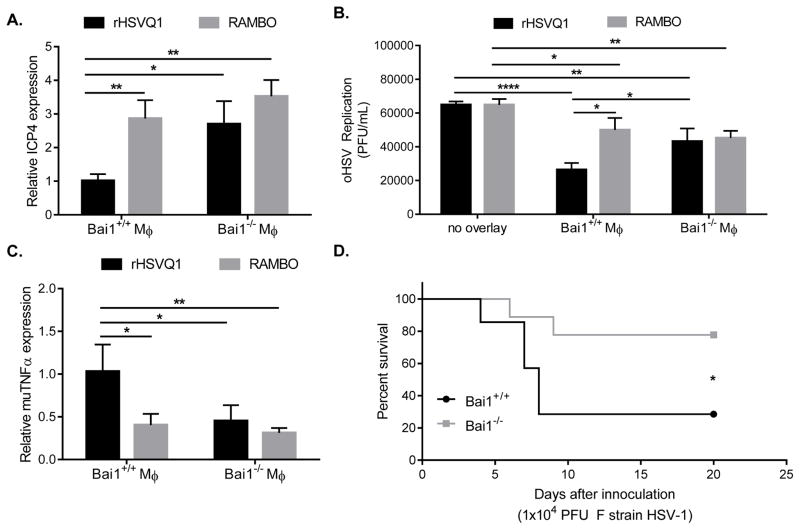

Effect of BAI1 receptor expression on macrophage response to oHSV

Since Vstat120 is the N-terminus of BAI1, and is expressed on macrophages, we reasoned that BAI1 could be involved in instructing an anti-viral function in macrophages, and Vstat120 may function as a decoy receptor. This would result in the negative regulation of BAI1-mediated anti-viral signaling. To first test if macrophage expression of Bai1 plays a role in its inflammatory response towards viral infection, we compared the antiviral effects of macrophages derived from Bai1/Adgrb1−/− (knock-out) or Bai1+/+ (wild-type) littermate mice. A significant increase in viral gene (ICP4) expression and replication was observed in rHSVQ1-infected human glioma cells cultured with Bai1−/− mouse macrophages compared to Bai1+/+ macrophages (Figure 5A,B; black bars). This result exposed an antiviral function of Bai1 that was rescued in macrophages from Bai1−/− mice. Viral replication of RAMBO infected co-cultures was significantly higher than rHSVQ1 co-cultures in the presence of Bai1+/+ macrophages (Figure 5A,B; black bars [rHSVQ1] vs. grey bars [RAMBO]). However, in the presence of Bai1−/− macrophages, the increase in ICP4 expression and viral replication was lost (Figure 5A,B; black bars [rHSVQ1] vs. grey bars [RAMBO]). These results revealed that while RAMBO tempered antiviral responses mediated by BAI1 in macrophages. The failure of Bai1−/− macrophages to antagonize rHSVQ1 replication was accompanied with a significantly reduced TNFα gene expression (Figure 5C). Overall, increased viral gene expression and replication in co-cultures with BAI1−/− macrophages revealed a role for BAI1 expression in virus clearance.

Figure 5. Reduced TNFα upon RAMBO infection depends on BAI1 expression in macrophages.

Primary bone marrow-derived murine macrophages from Bai+/+ or Bai1−/− mice were utilized to evaluate the impact of Bai1 on viral replication in co-culture with U251 glioma cells. (A) Twelve hours post infection, changes in viral ICP4 gene expression was compared between rHSVQ1 or RAMBO infected cells cultured with Bai1+/+ or Bai1−/− macrophages. Data shown is mean fold-change in ICP4 gene expression ± s.d., normalized to levels in rHSVQ1/Bai1+/+ co-culture. (B) Twelve hours post infection, changes in viral replication was compared between rHSVQ1- or RAMBO-infected U251 glioma cells cultured with Bai1+/+ or Bai1−/− macrophages. Data shown is mean replication (plaque-forming units/mL) ± s.d. (C) Change in murine TNFα gene expression was measured 12h after co-culture with infected U251 glioma cells. Data shown is relative TNFα gene expression ± s.d., normalized to expression in Bai1+/+ co-cultured with rHSVQ1. (D) Wild-type HSV-1 (F strain) was injected into naïve non-tumor-bearing brains of Bai1−/− or Bai1+/+ mice. Data shown is Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Mice were euthanized when they showed symptoms of viral encephalitis, including hunched posture, rough coat, thin body, or limb paralysis. (*, p≤0.05; **, p≤0.01; ****, p≤0.0001)

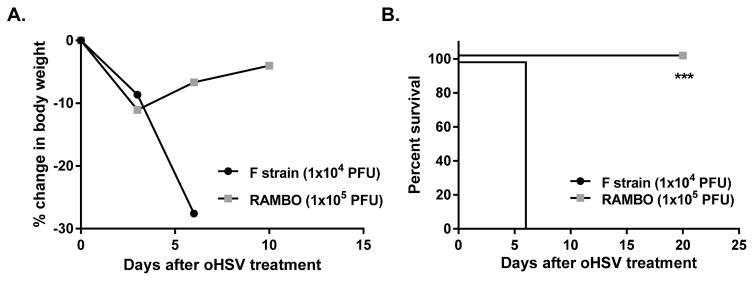

RAMBO is safe and effective in immune competent models

We next evaluated the importance of Bai1 receptor expression on wild-type HSV-1 infection in the brain. Using Bai1−/− mice or wild-type littermates, we intracranially inoculated mice with wild type F strain HSV-1, and monitored for survival. Bai1−/− mice showed significant resistance to HSV1-induced toxicity and survived longer than wild type littermates (Figure 5D). These results confirm that BAI1 receptor expression on macrophages plays a significant role in their response to both wild-type and oncolytic HSV therapy. Given the impact of Vstat120 on macrophage response to viral infection, we tested the safety of RAMBO in non-tumor bearing female BALB/C mice by direct intracranial inoculation of the virus. All mice treated with as little as 1x104 pfu of wild type HSV-1 F strain displayed rapid weight loss, neurological symptoms, and met early removal criteria by day 7 mandating their euthanization (Figure 6A,B). Mice treated with oncolytic RAMBO at a log fold higher dose (1x105 pfu) exhibited transient weight loss, but recovered by 7 days after treatment. Collectively, this experiment suggests that while RAMBO tempers the macrophage antiviral response allowing for better virus propagation in vivo and increased oncolytic efficacy, it can be safely pursued for clinical development.

Figure 6. RAMBO safety in immunocompetent mice.

Wild-type HSV-1 (F strain) or RAMBO was injected into naive non-tumor-bearing brains of HSV sensitive female Balb/C mice. (A) Change in percentage body weight of mice inoculated with wild type F strain HSV-1 or RAMBO. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice inoculated with wild type F strain HSV-1 or RAMBO. (***, p≤0.001)

Discussion

Angiogenesis is a hallmark of aggressive malignant glioblastoma, and numerous strategies to curb it using antibodies, small molecule inhibitors, etc. have been tested pre-clinically and in patients both as single agent and as combination strategies. Evaluation of changes in tumor microenvironment after oHSV therapy have uncovered changes in vascularization post therapy inciting several studies combining virotherapy with vascular disrupting agents and angiogenesis inhibitors (37). We have previously demonstrated increased anti-tumor effects when arming oHSV with Vstat120, a 120 kDa cleaved secreted fragment of BAI1, against a variety of preclinical cancer models, including glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, and head and neck cancer (6, 32, 38, 39). These effects had been heretofore attributed to the antiangiogenic effect of Vstat120 mediated by its conserved type I thrombospondin type I repeats (TSR), which bind to CD36 on endothelial cells and induce Fas-mediated apoptosis (12, 13). Here we demonstrate that arming an oHSV with Vstat120 also has a shielding effect against macrophages/microglia anti-viral responses.

Oncolytic HSV infections in brain tumor models typically generate a robust inflammatory response, leading to massive infiltration of macrophages/microglia in the tumor, which leads to a reduction in the anti-tumor efficacy of oHSV (29). Our current investigations revealed that brain tumor infection with RAMBO, an oHSV expressing Vstat120 showed a dramatic reduction in macrophage/microglial infiltrates compared with a control oHSV, rHSVQ1. These results demonstrate that Vstat120 expression in the context of an oHSV counters the inflammatory response towards oHSV. Increased virus propagation accompanied reduced macrophage infiltration into tumors treated with RAMBO compared to a control oHSV. In a co-culture system, RAMBO-infected glioma cells failed to activate a robust inflammatory cytokine response in macrophages. In particular, there was a strong reduction in TNFα gene expression and secretion by macrophages and microglia. Neutralization of TNFα in the co-culture with control oHSV reversed the anti-viral response and restored viral replication. These findings reveal TNFα to be a major effector that orchestrates the antiviral response of macrophages/microglia, and that it is antagonized by Vstat120.

BAI1 is known to function as a phagocytic receptor, which contributes to engulfment and clearance of apoptotic cells (14) and Gram-negative bacteria (18, 40). As an engulfment receptor, it functions via recognition and binding to phosphatidyl serine on apoptotic cells and to cell surface LPS of Gram-negative bacteria of infected cells (14, 16, 41) via its thrombospondin type 1 repeats (TSRs), triggering Rac1 activation of ELMO/Doc, resulting in increased phagocytic activity (18). Bai1 knockout mice exhibit impaired anti-microbial activity, and increased susceptibility to bacterial sepsis (40). Here our results show for the first time that, while wildtype primary bone marrow derived macrophages inhibited oHSV replication in co-cultured glioma cells, Bai1−/− macrophages were defective in their ability to curb virus replication, implicating an antiviral role for this multifunctional cell surface receptor.

Bai1−/− macrophage deficiency in mounting an anti-viral response against infected glioma cells was accompanied by a reduction in TNFα induction, mechanistically linking it to Vstat120’s effects. Along with the reduced TNFα, Bai1−/− mice were also more resistant to virus-induced pathology, corroborating the role of BAI1 in mediating inflammation in response to HSV-1 in the brain. Collectively, these results support a model whereby Vstat120 expression can inhibit TNFα production by blocking BAI1-mediated macrophage response to viral infection, and thus increase oHSV propagation in tumors. How Vstat120 might block the function of BAI1 in macrophage response to infected tumor cells is currently unclear, but we can envision two likely mechanisms. The first is a dominant negative competition model that assumes the extracellular domain of BAI1 is actively involved in the recognition of infected cells, likely through its TSRs. Vstat120 could shield infected tumor cells from macrophages/microglia by saturating all the BAI1 binding sites on the tumor cells. In the second model, Vstat120’s inhibitory action would occur directly on the macrophages/microglia. It has been shown that the cleaved extracellular domains of adhesion GPCRs stay associated with the 7-transmembrane region of the cleaved receptor, and act as antagonists (42). Detachment of the N-terminal fragment from the cleaved receptor activates receptor signaling. In this fashion, it is conceivable that Vstat120 might dampen a signal necessary for the macrophage anti-viral response. This second model also differs from the first one in that it does not assume that BAI1 is the prime sensor of the presence of infected cells by macrophages, it could also function in a co-stimulatory role.

Further investigations are warranted to determine whether BAI1 recognizes infected cells through a mechanism similar to its ability to clear bacterially-infected or apoptotic cells. It is possible that TSRs serve as recognition modules for a variety of pathogens. TSR are quite diverse in sequence, and the five TSRs in BAI1 share homology, but are not identical, suggesting that each TSR might confer the protein with unique substrate recognition abilities. Further studies with mutations in the individual TSRs of Vstat120 will help define their roles in the anti-inflammatory response. The signaling pathway that might trigger alterations in cytokine expression downstream of BAI1 remains to be identified. BAI1 can signal via several G-protein-dependent and independent pathways. It can activate small G proteins of the Ga12/13, as well as signal via Elmo/Dock/Ras or activate Erk signaling (43).

TNFα has been confirmed by multiple studies to play a critical role in tumor cell migration invasion, proliferation and angiogenesis. Additionally it is considered to be the major cytokine involved in cachexia, as well as systemic toxicity in patients. Consistent with this an oHSV encoding for TNFα was shown to increase systemic toxicity with no therapeutic advantage over control virus (44). Thus the reduction of TNFα in the context of virotherapy is of high potential significance. While long term abrogation of TNFα (such as in TNF−/− mice) has been associated with increased risk of wild type HSV-1 infection (45), transient blockade of TNFα along with anti-herpetic agents significantly increased the survival rate of mice inoculated with HSV-1 (46). These results support the involvement of inflammation in the pathogenesis of HSV-induced encephalitis, and efforts to combined HSV therapy with TNF-α inhibition can be a useful approach for oncolytic virus treatment. Consistent with this idea, we have previously shown that blockade of TNFα with a blocking antibody in mice bearing tumors led to increased virus replication and anti-tumor efficacy (22). Our study further shows that along with the moderation of TNFα and the resulting increased oHSV propagation in tumors, Vstat120-expressing oHSV remains safe at clinically relevant doses upon intracranial inoculation in non-tumor bearing mice. These studies encourage the further development of Vstat120-expressing oHSV as a therapeutic strategy to improve outcome for brain tumor patients.

Supplementary Material

Translational Significance.

Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1/ADGRB1) is an adhesion G-protein coupled receptor that serves as a scavenger receptor on macrophages implicated in bacterial and apoptotic cell clearance. Here we report that BAI1 directs macrophage-mediated virus clearance by inducing production of antiviral TNFα. This results in clearance of oncolytic HSV-1 (oHSV) viruses from a tumor which hinders oncolytic viral therapy. Proteolysis of BAI1’s N-terminus generates a 120 kDa fragment called vasculostatin (Vstat120) with potent antiangiogenic effects. Here we show that Vstat120 armed oHSV are also shielded from BAI1-mediated antiviral signaling, resulting in reduced tumoral inflammation and increased viral propagation in vivo. Further our results show that while attenuating antiviral responses by macrophages/microglia, leading to increased OV replication in vivo: this approach remains safe upon intracranial inoculation in animals. This study supports further development of this strategy for clinical development.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by: NIH grants R01NS064607, R01CA150153, P30NS045758 (to BK); P01CA163205 (to BK and MC), Pelotonia Fellowship to S. Dubin; T32CA009338 (to CB), IRG-67-003-50 (to JYY), P30CA016058 (to MC and BK), R01NS096236, P30CA138292, the Southeastern Brain Tumor Foundation (to EGVM) and the CURE Childhood Cancer and St. Baldrick’s Foundations (to EGVM and DZ).

We would like to acknowledge the Analytical Cytometry Shared Resource, the Center for Biostatistics, and the Target Validation Shared Resources within the James Comprehensive Cancer Center, all at The Ohio State University, for their services.

Footnotes

No Conflicts of Interest to Disclose.

References

- 1.Ahmed AU, Auffinger B, Lesniak MS. Understanding glioma stem cells: rationale, clinical relevance and therapeutic strategies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:545–55. doi: 10.1586/ern.13.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wojton J, Meisen WH, Kaur B. How to train glioma cells to die: molecular challenges in cell death. J Neurooncol. 2016;126:377–84. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1980-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veerapong J, Bickenbach KA, Shao MY, Smith KD, Posner MC, Roizman B, et al. Systemic delivery of (gamma1)34. 5-deleted herpes simplex virus-1 selectively targets and treats distant human xenograft tumors that express high MEK activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8301–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dmitrieva N, Yu L, Viapiano M, Cripe TP, Chiocca EA, Glorioso JC, et al. Chondroitinase ABC I-mediated enhancement of oncolytic virus spread and antitumor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1362–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, Amatruda T, Senzer N, Chesney J, et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2780–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardcastle J, Kurozumi K, Dmitrieva N, Sayers MP, Ahmad S, Waterman P, et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of vasculostatin (Vstat120) expressing oncolytic HSV-1. Mol Ther. 2010;18:285–94. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukushima Y, Oshika Y, Tsuchida T, Tokunaga T, Hatanaka H, Kijima H, et al. Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 expression is inversely correlated with vascularity and distant metastasis of colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:967–70. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.5.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatanaka H, Oshika Y, Abe Y, Yoshida Y, Hashimoto T, Handa A, et al. Vascularization is decreased in pulmonary adenocarcinoma expressing brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1) Int J Mol Med. 2000;5:181–3. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.5.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaur B, Brat DJ, Calkins CC, Van Meir EG. Brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 is differentially expressed in normal brain and glioblastoma independently of p53 expression. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:19–27. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63794-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Koh JT, Shin BA, Ahn KY, Roh JH, Kim YJ, et al. Comparative study of angiostatic and anti-invasive gene expressions as prognostic factors in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:355–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W, Da R, Wang M, Wang T, Qi L, Jiang H, et al. Expression of brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 is inversely correlated with pathological grade, angiogenesis and peritumoral brain edema in human astrocytomas. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1513–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klenotic PA, Huang P, Palomo J, Kaur B, Van Meir EG, Vogelbaum MA, et al. Histidine-rich glycoprotein modulates the anti-angiogenic effects of vasculostatin. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2039–50. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur B, Cork SM, Sandberg EM, Devi NS, Zhang Z, Klenotic PA, et al. Vasculostatin inhibits intracranial glioma growth and negatively regulates in vivo angiogenesis through a CD36-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1212–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park D, Tosello-Trampont AC, Elliott MR, Lu M, Haney LB, Ma Z, et al. BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature. 2007;450:430–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokolowski JD, Nobles SL, Heffron DS, Park D, Ravichandran KS, Mandell JW. Brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor-1 expression in astrocytes and neurons: implications for its dual function as an apoptotic engulfment receptor. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:915–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harre U, Keppeler H, Ipseiz N, Derer A, Poller K, Aigner M, et al. Moonlighting osteoclasts as undertakers of apoptotic cells. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:612–9. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.719950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott MR, Zheng S, Park D, Woodson RI, Reardon MA, Juncadella IJ, et al. Unexpected requirement for ELMO1 in clearance of apoptotic germ cells in vivo. Nature. 2010;467:333–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das S, Owen KA, Ly KT, Park D, Black SG, Wilson JM, et al. Brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1) is a pattern recognition receptor that mediates macrophage binding and engulfment of Gram-negative bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2136–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014775108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvarez-Breckenridge CA, Yu J, Price R, Wojton J, Pradarelli J, Mao H, et al. NK cells impede glioblastoma virotherapy through NKp30 and NKp46 natural cytotoxicity receptors. Nat Med. 2012;18:1827–34. doi: 10.1038/nm.3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haralambieva I, Iankov I, Hasegawa K, Harvey M, Russell SJ, Peng KW. Engineering oncolytic measles virus to circumvent the intracellular innate immune response. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2007;15:588–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda K, Ichikawa T, Wakimoto H, Silver JS, Deisboeck TS, Finkelstein D, et al. Oncolytic virus therapy of multiple tumors in the brain requires suppression of innate and elicited antiviral responses. Nature medicine. 1999;5:881–7. doi: 10.1038/11320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisen WH, Wohleb ES, Jaime-Ramirez AC, Bolyard C, Yoo JY, Russell L, et al. The Impact of Macrophage- and Microglia-Secreted TNFalpha on Oncolytic HSV-1 Therapy in the Glioblastoma Tumor Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3274–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakimoto H, Johnson PR, Knipe DM, Chiocca EA. Effects of innate immunity on herpes simplex virus and its ability to kill tumor cells. Gene Ther. 2003;10:983–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng KW, Myers R, Greenslade A, Mader E, Greiner S, Federspiel MJ, et al. Using clinically approved cyclophosphamide regimens to control the humoral immune response to oncolytic viruses. Gene therapy. 2013;20:255–61. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currier MA, Gillespie RA, Sawtell NM, Mahller YY, Stroup G, Collins MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of the oncolytic herpes simplex virus rRp450 alone and combined with cyclophosphamide. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2008;16:879–85. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiao J, Wang H, Kottke T, White C, Twigger K, Diaz RM, et al. Cyclophosphamide facilitates antitumor efficacy against subcutaneous tumors following intravenous delivery of reovirus. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14:259–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lun XQ, Jang JH, Tang N, Deng H, Head R, Bell JC, et al. Efficacy of systemically administered oncolytic vaccinia virotherapy for malignant gliomas is enhanced by combination therapy with rapamycin or cyclophosphamide. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15:2777–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haseley A, Boone S, Wojton J, Yu L, Yoo JY, Yu J, et al. Extracellular matrix protein CCN1 limits oncolytic efficacy in glioma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1353–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorne AH, Meisen WH, Russell L, Yoo JY, Bolyard CM, Lathia JD, et al. Role of cysteine-rich 61 protein (CCN1) in macrophage-mediated oncolytic herpes simplex virus clearance. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1678–87. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otsuki A, Patel A, Kasai K, Suzuki M, Kurozumi K, Chiocca EA, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors augment antitumor efficacy of herpes-based oncolytic viruses. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1546–55. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terada K, Wakimoto H, Tyminski E, Chiocca EA, Saeki Y. Development of a rapid method to generate multiple oncolytic HSV vectors and their in vivo evaluation using syngeneic mouse tumor models. Gene Ther. 2006;13:705–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo JY, Haseley A, Bratasz A, Chiocca EA, Zhang J, Powell K, et al. Antitumor efficacy of 34. 5ENVE: a transcriptionally retargeted and “Vstat120”-expressing oncolytic virus. Mol Ther. 2012;20:287–97. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu D, Li C, Swanson AM, Villalba RM, Guo J, Zhang Z, et al. BAI1 regulates spatial learning and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1497–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI74603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang H, Pengal RA, Cao X, Ganesan LP, Wewers MD, Marsh CB, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage inflammatory response is regulated by SHIP. J Immunol. 2004;173:360–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henry CJ, Huang Y, Wynne A, Hanke M, Himler J, Bailey MT, et al. Minocycline attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation, sickness behavior, and anhedonia. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Henry CJ, Dantzer R, Johnson RW, Godbout JP. Exaggerated sickness behavior and brain proinflammatory cytokine expression in aged mice in response to intracerebroventricular lipopolysaccharide. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1744–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur B, Chiocca EA, Cripe TP. Oncolytic HSV-1 virotherapy: clinical experience and opportunities for progress. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:1842–51. doi: 10.2174/138920112800958814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo JY, Yu JG, Kaka A, Pan Q, Kumar P, Kumar B, et al. ATN-224 enhances antitumor efficacy of oncolytic herpes virus against both local and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2015;2:15008. doi: 10.1038/mto.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolyard C, Yoo JY, Wang PY, Saini U, Rath KS, Cripe TP, et al. Doxorubicin synergizes with 34. 5ENVE to enhance antitumor efficacy against metastatic ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6479–94. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billings EA, Lee CS, Owen KA, D’Souza RS, Ravichandran KS, Casanova JE. The adhesion GPCR BAI1 mediates macrophage ROS production and microbicidal activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra14. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das S, Sarkar A, Ryan KA, Fox S, Berger AH, Juncadella IJ, et al. Brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 is expressed by gastric phagocytes during infection with Helicobacter pylori and mediates the recognition and engulfment of human apoptotic gastric epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2014;28:2214–24. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kishore A, Purcell RH, Nassiri-Toosi Z, Hall RA. Stalk-dependent and Stalk-independent Signaling by the Adhesion G Protein-coupled Receptors GPR56 (ADGRG1) and BAI1 (ADGRB1) J Biol Chem. 2016;291:3385–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.689349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephenson JR, Purcell RH, Hall RA. The BAI subfamily of adhesion GPCRs: synaptic regulation and beyond. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han ZQ, Assenberg M, Liu BL, Wang YB, Simpson G, Thomas S, et al. Development of a second-generation oncolytic Herpes simplex virus expressing TNFalpha for cancer therapy. J Gene Med. 2007;9:99–106. doi: 10.1002/jgm.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sergerie Y, Rivest S, Boivin G. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta play a critical role in the resistance against lethal herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:853–60. doi: 10.1086/520094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boivin N, Menasria R, Piret J, Rivest S, Boivin G. The combination of valacyclovir with an anti-TNF alpha antibody increases survival rate compared to antiviral therapy alone in a murine model of herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:649–53. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.