Abstract

Multilayered hard coatings with a CrN matrix and an Al2O3, TiO2, or nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer were designed by a hybrid deposition process combined with physical vapor deposition (PVD) and atomic layer deposition (ALD). The strategy was to utilize ALD thin films as pinhole-free barriers to seal the intrinsic defects to protect the CrN matrix. The influences of the different sealing layers added in the coatings on the microstructure, surface roughness, and corrosion behaviors were investigated. The results indicated that the sealing layer added by ALD significantly decreased the average grain size and improved the corrosion resistance of the CrN coatings. The insertion of the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers resulted in a further increase in corrosion resistance, which was attributed to the synergistic effect of Al2O3 and TiO2, both acting as excellent passivation barriers to the diffusion of corrosive substances.

Keywords: Multilayered hard coating, Hybrid deposition process, Sealing layer, PVD, ALD

Background

In industrial applications, damage and failure of numerous metal components result from corrosion. Protecting metals from corrosion is of great technical importance and significance, especially in aggressive environments. One of the most common methods of protection is to deposit protective films or coatings onto metal surfaces [1–3]. A variety of protective ceramic coatings, such as nitrides, carbides, silicides, and transition metal oxides, with relatively high corrosion resistance, wear resistance, and good mechanical strength, have been widely applied in the aviation, aerospace, electronics, petroleum, chemistry, machinery, textile, and automotive industries [4]. Among these protective ceramic coatings, chromium nitride (CrN) has been proven to be one of the most successfully and extensively used coatings in such industries due to its high hardness, excellent wear resistance, and remarkable stability against corrosion [5]. Until now, physical vapor deposition (PVD) techniques have been wildly used for synthesizing such coatings because no toxic chemical precursors are used and no toxic reaction gas or liquid bi-products are produced during the deposition process, which makes PVD to be introduced as an environmental friendly deposition process compared with the thermal chemical vapor deposition (CVD) or even plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) process [6, 7]. However, due to the line-of-sight transfer of vapor flux during the PVD process, the PVD coatings usually suffer from many intrinsic defects, including columnar structures, pinholes, pores, cracks, and discontinuities, which can significantly affect their corrosion resistance, especially when the substrates are active alloys, such as steel, or exposed to a chloride ion environment [8]. In recent years, to obtain dense microstructure of the coatings and overcome intrinsic defects to improve the corrosion resistance of the coatings, several approaches have been introduced. One such strategy is using more advanced deposition technologies, for example, high power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS), which exhibits several merits over conventional PVD sputtering, such as increased film density and good adhesion, as well as some advantages over vacuum arc deposition, e.g., free from macroparticles and smooth surface [9]. Another good approach is to add other elements (Si or B) into hard coatings to form nanocomposite coatings with nanosized crystallites surrounded by the matrix [10]. In addition, depositing coatings with multilayered structures can also overcome such intrinsic defects and improve the corrosion properties of hard coatings by synergistic effect of two or more materials [11, 12].

More recently, atomic layer deposition (ALD) techniques have gained great attention for corrosion protection because they are concerned with the requirements of thin film growth, such as uniformity, conformality, low-temperature processing, and exquisite thickness control, and potentially enable high-quality permeation barrier layers [13]. The corrosion protection abilities of ALD thin films, such as Al2O3, that directly perform on the surface of the substrates or hard coatings to protect the surface or block pinholes and other defects left in the structure have been reported [8, 14]. In our previous work, we demonstrated sandwich-structured coatings of CrN/Al2O3/CrN obtained using a hybrid deposition process combining HiPIMS and ALD, in which the consecutive ALD-Al2O3 thin film was inserted into the CrN matrix as a sealing layer. Our previous study showed that the ALD-Al2O3 film acted as a good insulating barrier with a low defect density and excellent passivation properties to block the diffusion of corrosive substances and improve the corrosion resistance of the CrN hard coatings [12]. However, the Al2O3 films were originally susceptible to corrosion in water, which means that they were not suitable for use in high humidity conditions or water [15]. In addition, aside from Al2O3, TiO2 is one of the most important reinforcement materials used as a protective layer in engineering materials and offers high strength, good oxidation, and corrosion resistance [4, 16]. Particularly, TiO2 is known to display excellent corrosion resistance against aqueous solutions, which makes it a promising candidate to remedy the drawbacks of Al2O3 sealing layers [17].

In this study, we aimed to further improve the passivation properties and corrosion resistance of the CrN/Al2O3/CrN hybrid coatings by adding ALD-TiO2 layers into the ALD-Al2O3 sealing layers. A multilayered CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 coating was designed and synthesized with a nanolaminate Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer (sub-layer thickness of ~2 nm) obtained by alternant deposition of Al2O3 and TiO2 by ALD, which was inserted at the middle position within the thickness of the CrN matrix coating. For comparison, CrN coatings with single sealing layer of Al2O3 or TiO2 were also synthesized. Based on our previous work, the ALD-Al2O3 layers have shown great passivation properties on highly dense and low-defect hard coatings by HiPIMS; however, the sealing efficiency of the ALD layers on less-dense coatings with pinholes and defects has been rarely studied. Therefore, in this work, relatively porous CrN matrix coatings with rough surfaces were deposited by using a conventional pulsed DC magnetron sputtering technique. The microstructure and corrosion behavior of the multilayered coatings with nanolaminate Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers in the porous CrN matrix coatings were systematically investigated.

Methods

The corrosion protection coatings were grown on well-polished stainless steels (SUS304) and Si (100) wafers that were cleaned and degreased by successive rinses in ultrasonic baths of acetone and alcohol for 15 min. The chemical composition of the SUS304 was C (0.044), Si (0.43), Mn (1.12), P (0.032), S (0.004), Ni (8.03), Cr (18.13), N (0.04), and Fe (in wt.%).

CrN Coating Deposition

The CrN coatings were deposited by using PVD at a temperature of 350 °C. First, a Cr adhesion layer was deposited to improve the coating adhesion. Then, the CrN layers were deposited from a Cr target (99.99%) in Ar (60 sccm) and N2 (30 sccm) gas at a working pressure of 4.8 × 10−3 Torr by using a pulsed DC sputtering power source, which was held constant at 0.8 kW, and a pulse ratio of 60%. A bias voltage of −100 V was applied to the substrates. The thickness of the CrN layers was controlled by adjusting the deposition time.

ALD Sealing Layer Deposition

To ensure the least possible contamination at the interface between the ALD and CrN, the as-deposited CrN samples were placed in the ALD chamber as soon as possible after removal from the PVD chamber. The ALD sealing layers, with a thickness of ~20 nm, were deposited on the pre-deposited CrN using a LUCIDA D100 ALD system at a low temperature of 150 °C. The individual Al2O3 and TiO2 sealing layers were obtained by using trimethylaluminum (Al(CH3)3), titanium isopropoxide (TTIP), and H2O reactant, respectively. During the Al2O3 and TiO2 deposition, canisters containing TMA, TTIP, and H2O were maintained at temperatures of 25, 60 and 10 °C to achieve a uniform precursor supply. The growth sequence of Al2O3 consisted of a 0.5 s TMA pulse, 10 s N2 purge, 1 s H2O pulse, and 10 s N2 purge, and of the growth sequence of TiO2 included a 0.1 s TTIP assist, 1 s TTIP pulse, 10 s N2 purge, 1 s H2O pulse, and 10 s N2 purge. Here, it was worth to mention that the “assist” step was performed for the TTIP pulse because the vapor pressure of TTIP is relatively low at 60 °C, i.e., a certain amount of N2 carrier gas was injected into the canisters for 0.1 s to increase the pressure of TTIP firstly and then released to the chamber for 1 s during the TTIP pulse. This “assist-mode” ensured the sufficient vapor pressure supply of the TTIP precursor during the deposition process. The nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers were obtained by repeated sub-cycles of Al2O3 and TiO2, respectively, as mentioned above, whereas the thickness of the unit cycles was fixed at ~2 nm for both, and the number of deposition cycles for each of the unit cycles was calculated using a growth rate per cycle (GPC) of ~1.5 Å/cycle for Al2O3 and ~0.3 Å/cycle for TiO2.

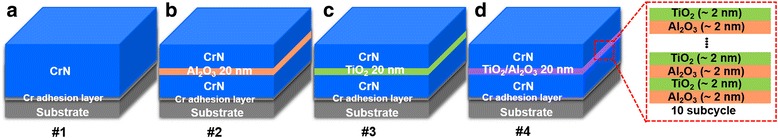

Generally, the pure CrN coatings and the configurations with Al2O3, TiO2, and nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers in the CrN coatings were deposited by adjusting the PVD deposition time and ALD deposition cycles, which were named as sample #1 (CrN), sample #2 (CrN-Al2O3), sample #3 (CrN-TiO2), and sample #4 (CrN-Al2O3/TiO2). The schematic illustrations of samples #1 to #4 and the deposition parameters are shown Fig. 1 and listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustrations of the cross-sectional structure. a Pure CrN coating. b CrN-Al2O3; CrN coating with a 20 nm Al2O3 sealing layer. c CrN-TiO2; CrN coating with a 20 nm TiO2 sealing layer. and d CrN-Al2O3/TiO2; CrN coating with a 20 nm nanolaminate-Al2O3/ TiO2 sealing layer

Table 1.

The deposition parameters of the PVD and ALD processes

| PVD deposition parameters | ALD deposition parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | TiO2 | ||||

| Deposition temperature | 350 °C | Precursor (TMA) | Cooling; 10 °C |

Precursor (TTIP) | Heating; 60 °C |

| Deposition time | 2 h | Reactant (H2O) | Cooling; 10 °C |

Reactant (H2O) | Cooling; 10 °C |

| Working pressure | 4.8 × 10−3 Torr | Purge gas | N2; 50 sccm | Purge gas | N2; 50 sccm |

| Ar flow rate | 60 sccm | Deposition temperature | 150 °C | Deposition temperature | 150 °C |

| N2 flow rate | 30 sccm | Line temperature | 100 °C | Line temperature | 100 °C |

| Bias voltage | 100 V | Growth rate | 1.5 Å/cycle | Growth rate | 0.3 Å/cycle |

Coating Characterization

An x-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8-Discovery Brucker, 40 kV) with 1.54 Å Cu-Kα radiation was used to identify the crystal structure of the films. The surface and cross-section micrographs of the coatings without and with ALD sealing layers were evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi, S-4800, 15 KV) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, asylum research MFD-3D). The CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 sample was chosen to further evaluate the ALD sealing effect of the CrN using transmission electron microscope (TEM, TALOS F200X) with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) after focused ion beam (FIB) sample preparation. The electrochemical properties of the coatings without and with ALD sealing layers were investigated by a three-electrode electrochemical cell using electrochemical workstation (Princeton, VersaSTAT 4). The potentiodynamic and potentiostatic polarization tests of the samples were obtained in 3.5 wt.% solutions of NaCl at room temperature. A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and platinum (Pt) mesh were used as the reference electrode and the counter electrode, respectively. All given potentials were reported vs. the SCE. The measurement range was from −1.0 to 1.2 V during the potentiodynamic tests, and the potential was fixed at 0.4 V for the potentiostatic tests because 0.4 V was the pitting region of the SUS304 substrate, which was reported in our previous study [12].

Results and discussion

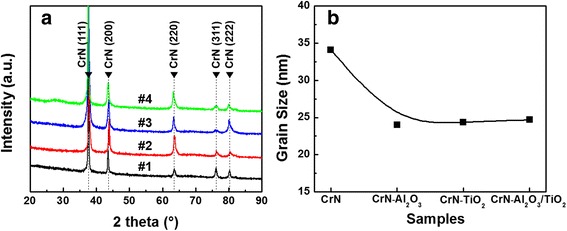

X-ray diffraction patterns of the as-deposited CrN and the multilayered coatings of CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2, and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 are shown in Fig. 2a. The diffraction patterns exhibited a cubic phase within the crystalline CrN film with mixed orientations of (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) crystal planes. No XRD peaks corresponding to other crystalline phases, such as Al2O3, TiO2, or other CrN phases, were observed, indicating the sealing layer had an amorphous structure and the insertion of the sealing layer did not provoke the phase transformation of the CrN matrix. The grain size was calculated by using Williamson-Hall method because it provides a better approach for estimating D than Scherrer’s formula, as reported previously [18]. As shown in Fig. 2b, the grain size of the multilayered coatings (approximately 24 nm) significantly decreased after inserting the sealing layer compared with that (approximately 34 nm) of the as-deposited CrN, which was attributed to the sealing layer interrupting the growth of the original CrN and the new nucleation of CrN grains regrowing on the ALD-modified surface during the second deposition process.

Fig. 2.

a XRD patterns and b average grain size of the pure CrN and CrN hybrid coatings with various sealing layers (CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2, and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2)

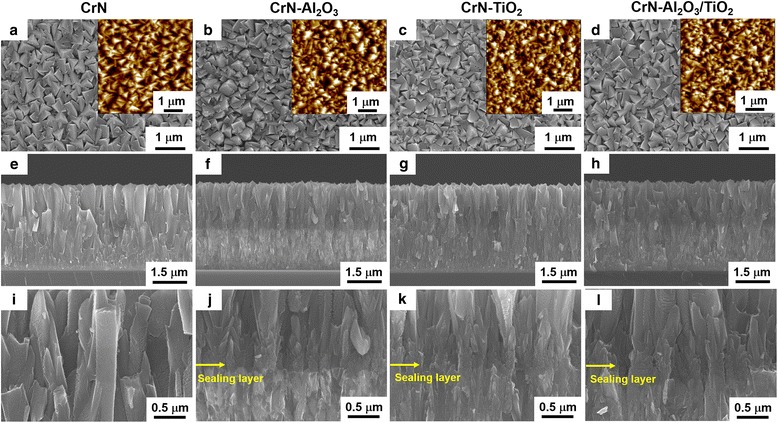

Figure 3 presents the top view and cross-sectional images of the as-deposited CrN and multilayered coatings of CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2, and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 by SEM observation. The as-deposited CrN exhibited a pyramid-like surface with a porous columnar structure, and the pinhole defects were clearly observed, as seen in Fig. 3a, e, and i, which consisted of long columnar grains and clear grain boundaries throughout the whole coating (approximately 3.5 μm). In contrast, the multilayered coatings showed denser and shorter columnar grain structures where the location of the sealing layer could be clearly confirmed. The interrupted morphologies indicated an intergranular fracture along the columnar grains, in which fine granular grains were developed throughout the coatings due to the new nucleation of the CrN on the modified surface after ALD sealing layer deposition. No obvious morphology changes were observed among the hybrid coatings with different sealing layers (Fig. 3f–h). Although pinhole defects could also be seen on the top of the CrN surface of the ALD sealed samples, it was expected that the ALD sealing layer could cover the pore walls along the grain boundary of CrN near the substrate. The cross-sectional observation of the CrN-Al2O3 shown in Fig. 3f, j exhibited the different contrast between the top CrN and bottom CrN, which was considered due to the successful deposition of the ALD oxide sealing layer, and this phenomenon with relatively weak contrast was also confirmed in the CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 specimen in Fig. 3h, l. The images inserted in Fig. 3a–d show the surface morphologies of the as-deposited CrN and multilayered coatings of CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2, and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 investigated by AFM. The acquired 5 μm × 5 μm images of the surface topography of these coating are presented. The root-mean-square (RMS) values of all specimens were approximately 60 nm, and no obvious changes of the RMS value were observed after the sealing layer insertion. However, based on the SEM and AFM analysis, a decrease in the grain size of the multilayered coatings (Fig. 3b–d) was demonstrated compared with the as-deposited CrN coating, which agreed well with calculation results of the grain size shown in Fig. 2b.

Fig. 3.

SEM surface images and cross-sectional images of the pure CrN and CrN hybrid coatings with various sealing layers. a, e, i CrN. b, f, j CrN-Al2O3. c, g, k CrN-TiO2. d, h, l CrN-Al2O3/TiO2. The corresponding AFM images were inserted in Fig. 3a–d

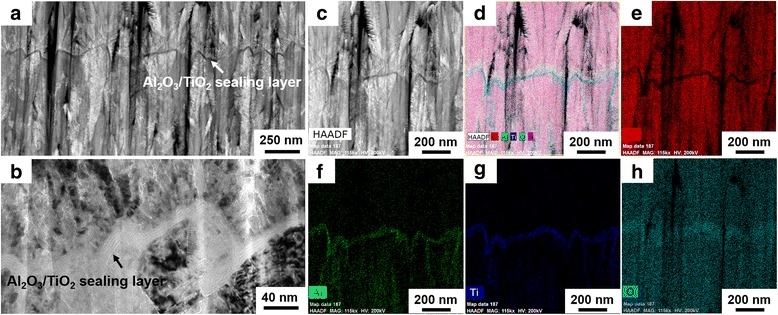

To confirm the uniformity of the ALD sealing layer, the hybrid coatings of CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 were chosen for further investigation by TEM/HRTEM/EDX after FIB preparation, which was presented in Fig. 4. As it is evident from Fig. 4a, there was a strong contrast difference in the CrN matrix and the nanolaminate sealing layer. A clear line (~20 nm) with dark contrast was considered to belong to the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer located in the CrN coatings (light contrast), where the uniform deposition of the ALD sealing layer on the rough surface of the first grown CrN could be confirmed evidently. In addition, a region with dense, small, and radiated new CrN sites was observed on the modified surface of the nanolaminate sealing layer, which was contributed to the nucleation of the new CrN grains at the initial stage of the second CrN deposition process. According to the HRTEM observations (Fig. 4b), the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer, combing of two types of individual Al2O3 and TiO2 sub-layers stacking together, could be evidently distinguished by the gray and white contrast, indicating the success of the ALD deposition process and ideal design of this experiment. The EDX analysis of the sealing layer is shown in Fig. 4c–h. The Al and Ti existed exactly within the inner CrN matrix as a clear thin layer. Moreover, Al and Ti were also detected as penetrating into the CrN coating along the CrN grain boundary, indicating that the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 layer not only efficiently sealed the surface of the first-grown CrN coating but also extended into the pinhole defects of the CrN to completely cover the walls even with very narrow gaps, which is one of the most attractive advantages of ALD that can deposit ultrathin films on complicated high aspect ratio structures with excellent coverage [19].

Fig. 4.

TEM/HRTEM/EDX analysis of the typical CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 hybrid coating: a low magnification bright field image. b HRTEM image of the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer. c-h EDX mapping results of Cr, Al, Ti and O elements

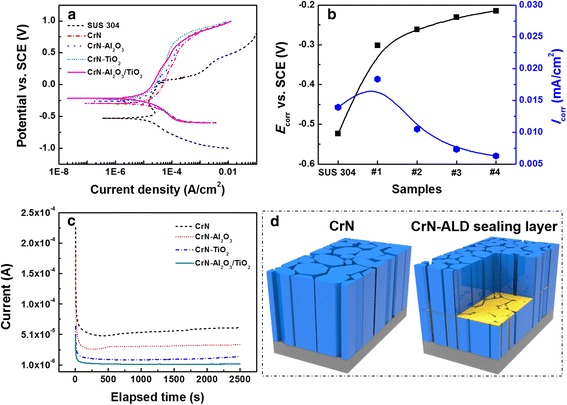

Potentiodynamic and potentiostatic polarization tests were performed to investigate the corrosion behavior. Figure 5 shows the polarization curves, corrosion current density (I corr) values vs. the corrosion potentials (E corr), and the current density depending on the exposure time of the pure CrN and multilayered coatings. As seen in Fig. 5a–b, high potentials could be observed after applying the hybrid coatings compared with the bare SUS304 sample both without and with the CrN coating. The I corr values were obtained from the Tafel plot by extending a straight line along the linear portion of the cathodic plot and extrapolating it to the E corr axis due to the non-symmetry of the polarization curve between the anodic and cathodic branches [20–22]. An inverse relation existed between I corr and E corr through the quantitative analysis of the potentiodynamic curves; the E corr continuously increased, while the I corr increased slightly for the pure CrN coating and then it decreased with the ALD sealing layer in the CrN. The increased I corr was considered due to the porous columnar CrN structure lead to some of the substrate exposing in the corrosion media. Therefore, a certain crevice corrosion rapidly would occur due to the localized attack during the corrosion investigation. And the final increase of the I corr after ALD sealing layer applying indicated an improvement of corrosion resistance of the hybrid coatings resulting from the good passivation properties of the ALD sealing layers. The hybrid coatings with the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers showed the best corrosion performance with the lowest I corr of ~6.26 × 10−6 A/cm2 and highest E corr of about −2.145 V, revealing that the nanolaminate Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layer proved to be more effective against corrosion in the corrosive media after applying the hybrid coatings. The current-time curves of CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2, and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 presented in Fig. 5c were acquired to verify the stability of the protection properties for a certain period at a given potential (E = 0.4 V vs. SCE) in the pitting region [12]. All of these curves showed a downward current density in the beginning. By comparison, the CrN exhibited a stable current density of approximately 5~6 × 10−5 A/cm2. However, after inserting the sealing layer, especially for the nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2, the lowest and most stable current density of 6~9 × 10−6 A/cm2 was achieved, reversing the good corrosion resistance of the coatings.

Fig. 5.

Potentiodynamic and potentiostatic curves of the SUS304 substrate, SUS304 substrate coated with CrN, CrN-Al2O3, CrN-TiO2 and CrN-Al2O3/TiO2 in 3.5 wt. % NaCl solution: a potentiodynamic curves. b calculation value of the corrosion potential and corrosion current density. c potentiostatic curves. d schematic illustration of corrosion behavior of the pure CrN coating and hybrid coating

Based on the microstructure and corrosion performance analysis, the mechanism of the hybrid coating defense from the attack of the corrosive media was discussed. In previous works of an ALD interlayer inserted into HiPIMS-CrN coatings, the ALD interlayer was mostly deposited at the interface of the CrN due to the dense structure with a few tiny defects [12]. Here, the PVD-CrN presented a highly porous structure, leading to an ALD layer that not only deposited on the surface of the first CrN but also covered the side walls of its grain boundaries and the pinhole defects, as shown in the schematic in Fig. 5d. As a result, the consecutive sealing layer with low defects could act as a barrier layer for blocking the diffusion of corrosive substances by covering the pore walls of the CrN. Additionally, the ALD sealing layer with poor conductivity could improve the electro resistance of the protective coatings as an insulating layer. The further enhanced corrosion performance was attributed to the combination of Al2O3 and TiO2 as the sealing layers. Both Al2O3 and TiO2 are good protective coatings for engineering materials and offer good oxidation and corrosion resistance [4]. Compared to Al2O3, TiO2 displays much better water resistance from water corrosion than Al2O3. In this work, the combination of the TiO2 and Al2O3 nanolaminates with both lower resistance and anti-water corrosion as the sealing layer exhibited more effective performance than the single layer configuration, which was attributed to the synergistic effect of both Al2O3 and TiO2 [17, 23].

Conclusions

In conclusion, CrN hybrid coatings were synthesized utilizing PVD and ALD techniques, and various sealing layers (Al2O3, TiO2, and Al2O3/TiO2) were inserted into the CrN matrix. By applying the ALD sealing layer, CrN coatings with denser microstructure were obtained, and the grain size of the coatings was decreased, while no change in the crystal structure was observed. The application of the ALD oxide sealing layer showed a positive effect on increasing the corrosion resistance of the CrN coatings. The ALD-TiO2 sealing layer indicated better corrosion resistance than the ALD-Al2O3 sealing layer. And the hybrid coatings with nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 sealing layers showed the best corrosion performance with the highest corrosion potential and the lowest current density in both potentiodynamic and potentiostatic polarization tests. The enhanced corrosion performance of nanolaminate-Al2O3/TiO2 was considered to attribute to the synergistic effect of ALD-Al2O3 with high electrical resistivity and ALD-TiO2 with high stability in aqueous corrosive media. The results demonstrate that the nanolaminate ALD-Al2O3/TiO2 is a promising candidate for effective sealing layer against corrosion in harsh conditions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Seong-Hee Jeong, Miss Ru-Ri Lee, and Miss Jong-Ah Chae for the help in AFM measurements, FIB sample preparation, and TEM investigation.

Funding

This research was mainly supported by the Global Frontier R&D Program (2013M3A6B1078874) on Center for Hybrid Interface Materials (HIM) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning, Republic of Korea. This research was also supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Promoting Regional Specialized Industry.

Authors’ Contributions

ZW designed the study, carried out ALD deposition, analyzed the experiment data, and drafted the manuscript. TFZ performed the deposition of the CrN hard coating and reconstruction of the data in the manuscript. JCD did the investigation of samples (XRD, SEM). CMK did the AFM investigation. SWP prepared the FIB specimen and drew the schematic diagram. YY, KHK, and SHK conceived the study, participated in its design, and supervised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AFM

Atomic force microscopy

- ALD

Atomic layer deposition

- CrN

Chromium nitride

- CVD

Chemical vapor deposition

- EDS

Energy dispersive spectrometer

- FIB

Focused ion beam

- HiPIMS

High power impulse magnetron sputtering

- GPC

Growth rate per cycle

- Pt

Platinum

- PECVD

Plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition

- PVD

Physical vapor deposition

- RMS

Root-mean-square

- SCE

Saturated calomel electrode

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- SUS

Stainless steels

- Al(CH3)3

Trimethylaluminum

- TEM

Transmission electron microscope

- TTIP

Titanium isopropoxide

- XRD

X-ray diffractometer

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: The first name of the author was missing in the original publication.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s11671-017-2079-8.

Contributor Information

Zhixin Wan, Email: wanshmily@gmail.com.

Teng Fei Zhang, Email: tfzhang@pusan.ac.kr.

Ji Cheng Ding, Email: jcdingxinyang@gmail.com.

Chang-Min Kim, Email: changmin.kim0317@gmail.com.

So-Won Park, Email: thdnjs1582@naver.com.

Yang Yang, Email: yangy@njtech.edu.cn.

Kwang-Ho Kim, Email: kwhokim@pusan.ac.kr.

Se-Hun Kwon, Email: sehun@pusan.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Shan C, Hou X, Choy KL. Corrosion resistance of TiO2 films grown on stainless steel by atomic layer deposition. Surf Coat Technol. 2008;202(11):2399–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.08.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ćurković L, Ćurković HO, Salopek S, Renjo MM, Šegota S. Enhancement of corrosion protection of AISI 304 stainless steel by nanostructured sol-gel TiO2 films. Corros Sci. 2013;77:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.07.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazar AM, Yespica WP, Marcelin S, Pébère N, Samélor D, Tendero C, Vahlas C. Corrosion protection of 304 L stainless steel by chemical vapor deposited alumina coatings. Corros Sci. 2014;81:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamoulid L, Maurette MT, Caro DD, Guenbour A, Bachir AB, Aries L, Hajjaji SE, Benoît-Marquié F, Ansart F. An efficient protection of stainless steel against corrosion: combination of a conversion layer and titanium dioxide deposit. Surf Coat Technol. 2008;202(20):5020–5026. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2008.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milošev I, Strehblow HH, Navinšek B. Comparison of TiN, ZrN and CrN hard nitride coatings: electrochemical and thermal oxidation. Thin Solid Films. 1997;303(1):246–254. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(97)00069-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha L, Andritschky M. Residual stress, surface defects and corrosion resistance of CrN hard coatings. Surf Coat Technol. 1999;111(2):158–162. doi: 10.1016/S0257-8972(98)00731-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis DB, Creasey SJ, Wüstefeld C, Ehiasarian AP, Hovsepian PE. The role of the growth defects on the corrosion resistance of CrN/NbN superlattice coatings deposited at low temperatures. Thin Solid Films. 2006;503(1):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2005.08.375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin E, Guzman L, Lanzutti A, Fedrizzi L, Saikkonen M. Chemical and electrochemical characterization of hybrid PVD + ALD hard coatings on tool steel. Electrochem Commun. 2009;11(10):2060–2063. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehiasarian AP, Münz WD, Hultman L, Helmersson U. High power pulsed magnetron sputtered CrNx films. Surf Coat Technol. 2003;163:267–272. doi: 10.1016/S0257-8972(02)00479-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barshilia HC, Deepthi B, Rajam KS. Deposition and characterization of CrN/Si3N4 and CrAlN/Si3N4 nanocomposite coatings prepared using reactive DC unbalanced magnetron sputtering. Surf Coat Technol. 2007;201(24):9468–9475. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purandare YP, Ehiasarian AP, Stack MM, Hovsepian PE. CrN/NbN coatings deposited by HIPIMS: a preliminary study of erosion-corrosion performance. Surf Coat Technol. 2010;204(8):1158–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2009.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan Z, Zhang TF, Lee HBL, Yang JH, Choi WC, Han B, Kim KH, Kwon SH. Improved corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of CrN hard coatings with an atomic layer deposited Al2O3 interlayer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(48):26716–26725. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b08696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Lee SM, Park CS, Lee SI, Lee MY. Substrate dependence on the optical properties of Al2O3 films grown by atomic layer deposition. Appl Phys Lett. 1997;71:3604–3606. doi: 10.1063/1.120454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Díaz B, Härkönen E, Światowska J, Maurice V, Seyeux A, Marcus P, Ritala M. Low-temperature atomic layer deposition of Al2O3 thin coatings for corrosion protection of steel: surface and electrochemical analysis. Corros Sci. 2011;53(6):2168–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim LH, Kim K, Park S, Jeong YJ, Kim S, Chung DS, Kim SH, Park CE. Al2O3/TiO2 nanolaminate thin film encapsulation for organic thin film transistors via plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(9):6731–6738. doi: 10.1021/am500458d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao W, Nabb D, Renevier N, Sherrington I, Luo JK. Mechanical and corrosion resistance properties of TiO2 nanoparticles reinforced Ni coating by electrodeposition. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2012;40:1–5. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/40/1/012043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdulagatov AI, Yan Y, Cooper JR, Zhang Y, Gibbs ZM, Cavanagh AS, Yang RG, Lee YC, George SM. Al2O3 and TiO2 atomic layer deposition on copper for water corrosion resistance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3(12):4593–4601. doi: 10.1021/am2009579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amaya-Vazquez MR, Sánchez-Amaya JM, Boukha Z, Botana FJ. Microstructure, microhardness and corrosion resistance of remelted TiG2 and Ti6Al4V by a high power diode laser. Corros Sci. 2012;56:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2011.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George SM. Atomic layer deposition: an overview. Chem Rev. 2009;110(1):111–131. doi: 10.1021/cr900056b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husain E, Narayanan TN, Taha-Tijerina JJ, Vinod S, Vajtai R, Ajayan PM. Marine corrosion protective coatings of hexagonal boron nitride thin films on stainless steel. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5(10):4129–4135. doi: 10.1021/am400016y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocchini G. The determination of tafel slopes by the successive approximation method. Corros Sci. 1995;37(6):987–1003. doi: 10.1016/0010-938X(95)00009-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose M, Williamson M, Willit J. Determining the exchange current density and tafel constant for uranium in LiCl/KCl eutectic. ECS Electrochem Lett. 2015;4(1):C5–C7. doi: 10.1149/2.0101501eel. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gselman P, Boncina T, Zupanic F, Panjan P, Merl DK, Cekada M. Characterization of defects in PVD TiAlN hard coatings. Mater Tehnol. 2012;46:351–354. [Google Scholar]