Abstract

Objective

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) may interfere with replication of hepatitis B (HBV) raising the hypothesis that HBV infection might be prevented by ART. We investigated the incidence and risk factors associated with HBV among HIV-infected adults in Rakai, Uganda.

Methods

We screened stored sera from 944 HIV-infected adults enrolled in the Rakai Community Cohort Study between September 2003 and March 2015 for evidence of HBV exposure. Serum from participants who tested anti-HBc negative (497) at baseline were tested over 3-7 consecutive survey rounds for incident HBV. Poisson incidence methods were used to estimate incidence of HBV with 95% confidence intervals while Cox proportional regression methods were used to estimate hazard ratios.

Results

39 HBV infections occurred over 3,342 person-years (p-y), incidence 1.17/100 p-y. HBV incidence was significantly lower with ART use: (0.49/100 p-y) with ART and (2.3/100 p-y) without ART [aHR=0.25 (95% CI, 0.1-0.5) p<0.001], and with lamivudine (3TC) use: (0.58/100 p-y) with 3TC and (2.25/100 p-y) without 3TC [aHR= 0.32(0.1-0.7), p=<0.007)]. No new HBV infections occurred among those on tenofovir-based ART. HBV incidence also decreased with HIV RNA suppression: (0.6/100 p-y) with ≤400 copies/mL and (4.0/100 py) with >400 copies/mL [aHR= 6.4(2.2-19.0), p<0.001] and with age: 15-29 years vs 40-50 years [aHR=3.2 (1.2-9.0)]; 30-39 years vs 40-50 years [aHR=2.1(0.9-5.3)].

Conclusion

HBV continues to be acquired in adulthood among HIV-positive Ugandans and HBV incidence is dramatically reduced with HBV-active ART. In addition to widespread vaccination, initiation of ART may prevent HBV acquisition among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

Both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B (HBV) are highly endemic in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). According to the 2014 UNAIDS report, 70% of the global HIV disease burden (36.9 million) is in this region(1), which also has the second highest number of individuals with chronic HBV infection (15% of the 350-400 million) in the world (2, 3). Globally, coinfection with HBV is common among HIV infected patients and accelerates the progression of liver disease to cirrhosis, end stage liver disease and liver cancer, thereby threatening to reverse the survival benefit that has been derived from the scale up of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) (4, 5). There are also data that suggest that HBV may accelerate HIV progression in SSA (6). Among men who have sex with men and IV drug users in the US, there is a strong association between the incidences of both HIV and HBV (7). This association is however less clear in SSA where HIV is predominantly transmitted via the heterosexual route and HBV horizontally during childhood (8, 9). Data on HBV incidence is scarce but emerging evidence suggests ongoing sexual transmission of this disease among HIV infected adults (10, 11), who represent a high risk group for HIV acquisition.

Including HIV infected persons among the priority groups for HBV vaccination in SSA would require data demonstrating the rate at which new HBV infections occur in this subpopulation. In addition, this dynamic might be affected by ART since it often includes medications like lamivudine and tenofovir that are also active against HBV and might prevent HBV infection. The aim of this study was to measure the incidence of HBV and to test the hypothesis that ART reduces HBV incidence by exploring risk factors associated with HBV among the HIV infected individuals in Uganda.

Methods

Study participants

This study was conducted at the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP), a large HIV research and treatment center in rural Southwestern Uganda. The RHSP, through its longitudinal Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS), performs population-based surveys in 50 communities at approximately 18 month intervals. In each survey, sera and demographic data are collected from over 14,000 individuals aged 15-49 years, with the primary purpose of monitoring trends of HIV infection in this region. From the RCCS, we identified 944 HIV infected individuals who had archived sera that had been obtained during at least four RCCS survey rounds conducted between September 2003 and March 2015. We screened the 944 baseline samples for evidence of HBV exposure using the hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) serological marker. Participants who tested anti-HBc positive at baseline were excluded from this study while those that tested negative were included in the study. Their serum samples collected over 3 to 7 survey rounds after the baseline survey were serially tested for both anti-HBc and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) at each survey round with an available sample or until these markers became positive. HBV seroconverters had their baseline sera tested for HBsAg to confirm that they were HBsAg negative at baseline.

The testing for anti-HBc and HBsAg was performed by EIA technique (Murex Biotech Limited, Dartford, UK). The time of HBV incidence was defined as the median date between the last anti-HBc/HBsAg negative sample and the first positive anti-HBc or HBsAg serum sample. Infection was defined by a positive HBsAg and/or anti-HBc test result.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology.

Outcomes and measurements

The primary outcome was incident HBV infection defined as the sero-conversion to either anti-HBc or HBsAg or both. Exposures evaluated as risk factors for HBV acquisition included socio-demographic and clinical factors; age, sex as fixed baseline characteristics, and occupation, marital status, number of sexual partners, ART, CD4 T-cell count and HIV viral load as time varying covariates at each survey round. Only viral loads within 12 months of the survey round and CD4 counts within six months of the survey round were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Exact Poisson incidence methods were used to estimate the incidence of HBV with 95% confidence intervals while the Cox proportional regression methods accounting for time-updated exposure variables were used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios of ART use and other confounders. Cumulative hazards of infection by age and ART use were estimated with the Kaplan Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Person time of exposure for the non-converters was computed as the time from the baseline HBV negative test date to the last negative test date, and as the time from baseline HBV negative test date to the mid-point of the last negative HBV result and the first HBV positive test date for the sero-converters. Sub analyses for estimating the effect of single or dual HBV active drugs and suppressed viral load (i.e viral load <400 copies/ml) were performed. Data were analyzed using STATA software 14 package (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

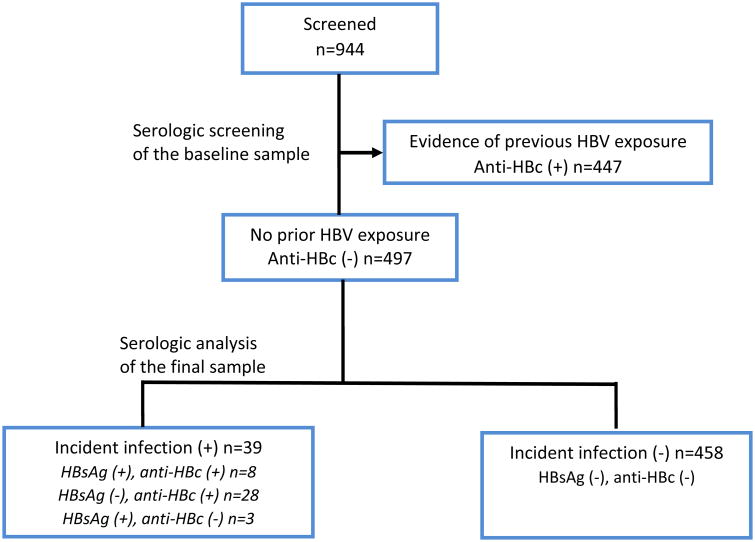

The participant selection process is summarized in Figure 1. Of the 944 individuals who were eligible for screening, 447 (47%) were either previously or currently infected with HBV at the time of baseline serum sampling;the remaining497 (53 %) who tested negative for the anti-HBc marker were subsequently enrolled.

Figure 1. Flowchart of selected participants.

Participant selection process: A total of 944 patients met the inclusion criteria described in the methods sections. Of these, 447 were excluded because of they had been previously been infected with HBV in their baseline samples. The remaining individuals were enrolled. The results of the laboratory tests are as summarized above. Anti-HBc = antibody to HBV core antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen

The study population was mainly composed of young individuals, median age 30 (IQR 25-34), women (71%) and those with preserved CD4 T-cell count, median 446/mm3 (IQR=251-630). The majority (70%) reported one sexual partnerin the last year. In contrast, the HBV-infected individuals at baseline were more likely to be older, male, currently or previously married and to have had at least two partners in the last year (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants infected and not infected with hepatitis B at baseline.

| Not Infected | Infected | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristics | N(%) | N(%) | |

| Overall | 497 (53%) | 446 (47%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 354 (71%) | 280 (63%) | 0.007 |

| Male | 143 (29%) | 165 (37%) | |

| Median AGE(years) | |||

| AGE (years) | |||

| 40+ | 50 (10%) | 80 (18%) | <0.001 |

| 30-39 | 208 (42%) | 219 (49%) | |

| 15-29 | 239 (48%) | 146 (33%) | |

| Median CD4(cells/ul)* | |||

| CD4 (cells/ul)* | |||

| 0-99 | 7 (6%) | 6 (6%) | 0.882 |

| 100-250 | 22 (19%) | 18 (17%) | |

| 251-500 | 41 (35%) | 42 (40%) | |

| 500+ | 48 (41%) | 39 (37%) | |

| SEX PARTNERS IN LAST 1 YEAR | |||

| 0 | 58 (12%) | 68 (15%) | 0.034 |

| 1 | 348 (70%) | 276 (62%) | |

| >=2 | 91 (18%) | 101 (23%) | |

| MARITAL STATUS | |||

| Never married | 68 (14%) | 37 (8%) | 0.009 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 293 (59%) | 257 (58%) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 136 (27%) | 151 (34%) | |

| OCCUPATION | |||

| Agriculture | 279 (56%) | 260 (58%) | 0.859 |

| Fishing/Brewer/Motorbycle | 27 (5%) | 26 (6%) | |

| Trader/Formal employment | 107 (22%) | 83 (19%) | |

| Unemployed/Home maker | 79 (16%) | 73 (16%) | |

| Other | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |

Only 4% (22/497) patients were on ART at baseline and an additional 53% (265/497) initiated ART during the course of the study contributing 2054 person years (p-y) of ART use of the total 3342 p-y in the study representing 62% of the total observation time. Of the patients that were on ART, 69% (199/287) had documented ART regimen information and 91% (262/287) had viral load data within one year of a study visit. Among participants with documentation of ART regimen, use of 3TC without TDF was most common (1215 p-y, comprising 85% of all ART use p-y), the combination of 3TC and TDF was used for 213 p-y (14.9 of recorded p-y), and neither 3TC nor TDF were included in the regimens of only 4 p-y (0.3%).

During the study period, 39 participants seroconverted to anti-HBc, had detectable HBsAg, or both. Overall, the 497 participants accrued 3,342 person years (p-y) during which 39 infections (8 positives for both HBsAg and anti-HBc, 3 for HBsAg only and 28 for anti-HBc only) occurred, yielding an incidence 1.17/100 (95%CI, 0.8-1.6) p-y.

HBV incidence was higher in persons who were younger (Table 2). Among those 15-29 years incident HBV infection was more than 3-fold higher than for those who were 40-50 years of age [aHR=3.24 (95% CI,1.2-9.0)]. There were no statistically significant differences by gender, occupation, marital status, number of sex partners, duration on ART or baseline CD4 count.

Table 2. Incidence and Factors associated with Incident HBV Infection.

| Characteristics | Cases/Person years | Incidence/100 person years | Unadjusted HRs (95% CI) | p-values | Adjusted HRs (95% CI) | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 39/3342 | 1.17 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 30/2381 | 1.26 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Male | 9/962 | 0.94 | 0.74(0.3-1.6) | 0.434 | 0.80(0.4-1.7) | 0.573 |

| AGE (years) | ||||||

| 40+ | 6/1239 | 0.48 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 30-39 | 22/1649 | 1.33 | 2.76(1.1-6.9) | <0.001 | 2.12(0.9-5.3) | 0.080 |

| 15-29 | 11/456 | 2.42 | 4.98(1.8-13.9) | 3.24(1.2-9.0) | ||

| CD4 count* | ||||||

| 0-99 | 1/54 | 1.87 | Ref | |||

| 100-250 | 3/213 | 1.41 | 0.74(0.1-7.5) | 0.955 | ||

| 251-499 | 12/742 | 1.62 | 0.87(0.1-7.0) | |||

| 500+ | 12/921 | 1.30 | 0.70(0.1-5.6) | |||

| HIV Viral load (copies/ml)** | ||||||

| ≤400 | 7/1175 | 0.60 | Ref | Ref | ||

| >400 | 8/200 | 4.00 | 6.27(2.3-17.0) | <0.001 | 6.41(2.2-19.0) | 0.001 |

| On ART | ||||||

| No | 29/1288 | 2.25 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 10/2055 | 0.49 | 0.21(0.1-0.4) | <0.001 | 0.25(0.1-0.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex partners in last 1 year | ||||||

| 0 | 8/812 | 0.99 | Ref | |||

| 1 | 25/2091 | 1.20 | 1.21(0.5-2.7) | 0.836 | ||

| >=2 | 6/440 | 1.36 | 1.38(0.5-4.1) | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 5/260 | 1.93 | Ref | |||

| Married/Cohabiting | 16/1810 | 0.88 | 0.46(0.2-1.3) | 0.216 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 18/1273 | 1.41 | 0.73(0.3-2.0) | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Agriculture | 22/1679 | 1.31 | Ref | |||

| Fishing/Brewer/Motorcycle | 2/134 | 1.50 | 1.15(0.3-5.2) | 0.451 | ||

| Trader/Formal employment | 11/804 | 1.37 | 1.06(0.5-2.2) | |||

| Unemployed/Home maker | 3/220 | 1.37 | 1.04(0.3-3.6) | |||

| Other | 1/508 | 0.20 | 0.15(0.0-1.1) |

377 patients had CD4 results available

262 subjects had viral load results, and 287 were on ART

ART=Antiretroviral Therapy

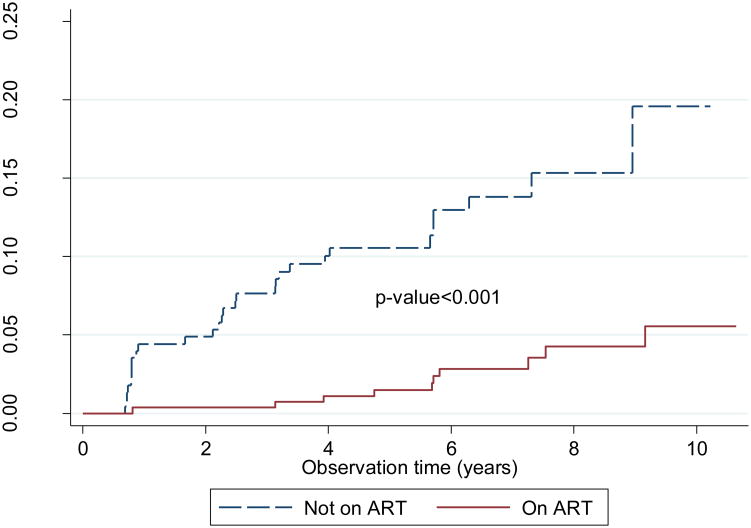

HBV incidence was significantly lower with ART use: 0.49/100 p-y with ART use and 2.25/100 p-y in the absence of ART [aHR=0.25 (95% CI, 0.1-0.5) p<0.001]. HBV incidence was also lower in persons whose HIV RNA was suppressed (indication of receipt and adherence to ART). The incidence was 0.6/100 p-y in those with HIV RNA ≤400 copies/mL and 4.0/100 p-y in those with >400 copies/mL [aHR= 6.4 (95% CI, 2.2-19.0), p<0.001]. On multivariate analysis, the protective association of ART on HBV incidence increased after controlling for viral suppression (HR=0.14, CI .027- 0.76, p=0.02) but the association of viral suppression diminished after controlling for the absence of HBV active ART (HR=1.73 (CI 0.38- 7.93, p=0.48).

With regard to ART use, 99% (198/199) of ART regimens contained 3TC either as the only HBV active medication (171) or in combination with tenofovir (27). Three individuals were on a combined pill of tenofovir (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC), and one was on a regimen that contained no HBV active medication. No individual was on FTC without TDF. For the purpose of this study, individuals on FTC were analyzed as having received 3TC since the two medications have closely related pharmacological properties. To further explore the effect of ART on incident HBV, the analysis was stratified by whether the ART regimen contained the HBV-active medications 3TC/FTC or tenofovir (TDF) as follows: no ART if they had never initiated ART, 3TC-based ART if on a 3TC regimen that did not contain TDF, TDF-based ART if on TDF plus either 3TC or FTC, or no HBV active ART if on a regimen that did not contain either TDF, 3TC or FTC. HBV incidence significantly differed by 3TC use: 0.58/100 p-y in those taking 3TC compared with 2.25/100 in those not taking 3TC or TDF [aHR= 0.32(95% CI, 0.1-0.7), p=0.007)] (table 3). No new HBV infection occurred among individuals during the 213 p-y on TDF and 3TC combination-based ART regimen.

Table 3. Association of ART Regimen with the Incidence of Hepatitis B Infection.

| Characteristics | Unadjusted HRs | Adjusted HRs** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/Person years (pys) | Incidence/100 person years | 95% CI | p-values | 95% CI | p-values | |

| ART Regimen* | ||||||

| No ART | 29/1288 | 2.25 | Ref | |||

| 3TC without TDF | 7/1215 | 0.58 | 0.25(1.0-0.6) | 0.001 | 0.32(0.1-0.7) | 0.007 |

| 3TC and TDF | 0/213 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Missing 3TC/TDF | 0/4 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - |

Excludes 88 subjects that had initiated ART but their Regimen information is missing.

Adjusted for Age and Gender

ART= antiretroviral therapy, 3TC= lamivudine or emtricitabine (FTC), TDF= tenofovir

To exclude the possibility of very early HBV infection (in which the HBsAg is detectable and anti-HBc is undetectable), the baseline samples of 39 serocoverters were tested for HBsAg. Thirty-one subjects tested negative while 8 participants had inadequate sera for this test. ART use remained associated with a lower incidence of HBV infection in a sub analysis in which of these 8 participants were excluded.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in SSA to evaluate the incidence of HBV in a HIV infected adult population and the impact of ART on HBV acquisition. We found that HBV incidence was high in this group and that ART may have a protective role in preventing HBV infections among HIV-infected adults.

The high incidence of HBV infection in this study is consistent with data reported from studies in Europe, USA and Japan where MSM and IV drug users constitute the high risk groups for HBV infection. In these studies incident HBV rates among MSM ranged from 0.12-1.49 cases per 100 p-y but were much lower in the non-MSM individuals as well as the HIV uninfected counterparts(12, 13). In the RCCS in rural Uganda, our clinical and epidemiological data suggest that HBV is primarily transmitted through heterosexual contacts rather than MSM or IVDU high risk groups reported elsewhere.

Recent studies from the European Union and Japan also have suggested a pre-exposure protective effect of HBV active ART medications particularly TDF and 3TC (12-14). Our study is unique in that it showed a protective effect of 3TC only containing regimens in a population where heterosexual HIV transmission is believed to dominate. HIV viral load suppression on ART was a strong predictor of the protective effect of ART against incident HBV in our study, consistent with earlier findings (14, 15). The mechanism of this effect could be direct suppression of HBV replication or inhibition of HIV replication altering the biology of HBV acquisition.Failure to suppress HIV could also be associated with poor adherence and higher risk behaviors that predispose to HBV infection (16). In this study, the increased protective association of ART after controlling for viral suppression and the reduced effect of viral suppression on HBV incidence after controlling for the absence of HBV active ART suggest that the protective effect of suppressed HIV viral load is a measure for effectiveness of ART and not a viral load specific effect.

We found no relationship between the baseline CD4 T-cell count and duration on ART with incident infection. These results should be interpreted with caution as few patients in our cohort had T-cell counts below 200 cells / mm3 and baseline T-cell counts were missing in the majority of our included participants.

Incident HBV in our study was inversely related to age. The occurrence of the majority of HBV infections between the 15-29 and the 30-39 age groups supports earlier reports from prevalence studies that suggested that sexual intercourse was yet another important route of HBV disease transmission among SSA adults(10, 11). In our study however, only a non-statistically significant association was detected between incident HBV infection and the number of sex partners in the last yearpossibly due to under-reporting of this information by study participants.

Our study has some limitations. We used a convenience sample of HIV-infected individuals with available serum from at least 4 time points, and retrospectively analyzed sera and data from a cohort that was not originally designed to answer our research question; thus, we had missing and incomplete data on some study parameters such as HBV disease risk factors. However, since the blood samples, socio-demographic and clinical parameters were collected prospectively from a community cohort, and serum sample decay (in relation to HBV serological studies) is unlikely to have occurred, our study findings are more reflective of the community HBV incidence than hospital based studies. Baseline serum samples were tested for anti-HBc and not for anti-HBs. There is no universal adult vaccination program against HBV in Uganda and the childhood vaccination under the Uganda national expanded program on immunization began in 2002, it is highly unlikely that our study participants, aged 15-49, could have acquired immunity to HBV through vaccination.

In conclusion, we find that there is ongoing HBV transmission among HIV infected adults in SSA. The overall high incidence of HBV in this population and the protective association of ART demonstrate yet another potential benefit to expanding the ART rollout throughout SSA, and possibly initiating ART at time of HIV diagnosis. The findings also suggest HBV vaccination of HIV-infected persons should be integrated into HIV treatment programs in these highly endemic regions.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meier curves for hepatitis B survival-free survival in relation to ART use. The blue and red lines represent hazards for individuals when not on ART and when on ART respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Rakai Community Cohort Study within the Rakai Health Sciences Program whose hard work contributed to the current study.

Funding: This study was funded in part by a D43 Grant on HIV-associated malignancies sponsored by the US National Institute of Health (D43 CA153720-01), NIH research training grant R25TW009345 funded by the Fogarty International Center through the Fogarty Global Health Fellowship, and the University of Washington / Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research (NIH award P30 AI027757). Funding was also obtained from the Division of Intramural Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)AI001040, National Institutes of Health, D43TW010132 and through the U54 consortium (Federal award number: U54CA190165-02, Sub award No.2002389678). The RCCS was supported by the following NIH: grants UO1 AI11171-01-02, U01 AI51171, U01 AI075115-01A1, R01 AI47608, R37DA013806, R01 AI114438, R01 AI110324, U01 AI100031 and D43 CA 153720 from NIAID and grants HD070769 and HD 050180 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD), Grant 22006 from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and support from The World Bank.

This project was also funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or any of the other funding Institutions, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Author Contributions: Study design: ES, SR, CC, OP, WP, DLT

Study conduct: SK, SR ES

Design of data analysis: VS SR ES DLT

Writing of the manuscript: ES, SR, CC, PO, DS, MJW, RHG, WT, FN, SK, VS, DLT.

References

- 1.The 2014 UNAIDS Global Statistics fact sheet

- 2.Matthews PC, Geretti AM, Goulder PJ, Klenerman P. Epidemiology and impact of HIV coinfection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2014;61(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elizabeth W, Hwang M, Ramsey Cheung MD. Global Epidemiology of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection N A J Med Sci. 2011;4(1):7–13. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber R, Ruppik M, Rickenbach M, Spoerri A, Furrer H, Battegay M, et al. Decreasing mortality and changing patterns of causes of death in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV medicine. 2013;14(4):195–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi D, O'Grady J, Dieterich D, Gazzard B, Agarwal K. Increasing burden of liver disease in patients with HIV infection. Lancet (London, England) 2011;377(9772):1198–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idoko J, Meloni S, Muazu M, Nimzing L, Badung B, Hawkins C, et al. Impact of hepatitis B virus infection on human immunodeficiency virus response to antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;49(8):1268–73. doi: 10.1086/605675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konopnicki D, Mocroft A, de Wit S, Antunes F, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, et al. Hepatitis B and HIV: prevalence, AIDS progression, response to highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased mortality in the EuroSIDA cohort. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19(6):593–601. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163936.99401.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdool Karim SS, Coovadia HM, Windsor IM, Thejpal R, van den Ende J, Fouche A. The prevalence and transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in urban, rural and institutionalized black children of Natal/KwaZulu, South Africa. International journal of epidemiology. 1988;17(1):168–73. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardas E, Mathai M, Blaauw D, McAnerney J, Coppin A, Sim J. Preimmunization epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in South African children. Journal of medical virology. 1999;58(2):111–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stabinski L, Reynolds SJ, Ocama P, Laeyendecker O, Serwadda D, Gray RH, et al. Hepatitis B virus and sexual behavior in Rakai, Uganda. Journal of medical virology. 2011;83(5):796–800. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bwogi J, Braka F, Makumbi I, Mishra V, Bakamutumaho B, Nanyunja M, et al. Hepatitis B infection is highly endemic in Uganda: findings from a national serosurvey. African health sciences. 2009;9(2):98–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatanaga H, Hayashida T, Tanuma J, Oka S. Prophylactic effect of antiretroviral therapy on hepatitis B virus infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;56(12):1812–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuft MM, Houba SM, van den Berk GE, Smissaert van de Haere T, van Dam AP, Dijksman LM, et al. Protective effect of hepatitis B virus-active antiretroviral therapy against primary hepatitis B virus infection. AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(7):999–1005. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shilaih M, Marzel A, Scherrer AU, Braun DL, Kovari H, Rougemont M, et al. Dually Active HIV/HBV Antiretrovirals Protect Against Incident Hepatitis B Infections: Potential for Prophylaxis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falade-Nwulia O, Seaberg EC, Snider AE, Rinaldo CR, Phair J, Witt MD, et al. Incident Hepatitis B Virus Infection in HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Men Who Have Sex With Men From Pre-HAART to HAART Periods: A Cohort Study. Annals of internal medicine. 2015 doi: 10.7326/M15-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond C, Richardson JL, Milam J, Stoyanoff S, McCutchan JA, Kemper C, et al. Use of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy is associated with decreased sexual risk behavior in HIV clinic patients. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2005;39(2):211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]