Abstract

Objective

To present the outcomes of posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) double-bundle reconstruction using autologous hamstring tendons, with a minimum follow-up of two years.

Methods

Evaluation of 16 cases of PCL injury that underwent double-bundle reconstruction with autogenous hamstring tendons, between 2011 and 2013. The final sample consisted of 16 patients, 15 men and one woman, with a mean age of 31 years (21–49). The predominant mechanism was motorcycle accident in half of the cases. There was a mean interval of 15 months between the time of lesion and the surgery (three to 52 months). Five lesions were isolated and 11, associated. Clinical evaluation, application of validated scores, and measurements with use of the KT-1000 were performed.

Results

The analysis showed a mean preoperative Lysholm score of 50 points (28–87), progressing to 94 points (85–100) postoperatively. The IKDC score also demonstrated improvement. In the preoperative evaluation, four and 12 patients were respectively classified as C (abnormal) and D (very unusual), and in the postoperative evaluation six as A (normal) and ten as B (close to normal). In the post-operative evaluation by KT1000 arthrometer, 13 patients showed difference between 0–2 mm and 3 between 3 and 5 mm, when compared with the contralateral side.

Conclusion

Autologous hamstring tendons are a viable option in double-bundle reconstruction of the PCL, with good clinical results in a minimum follow-up of two years.

Keywords: Knee/surgery, Posterior cruciate ligament, Knee injuries, Evaluation of results of therapeutic interventions

Resumo

Objetivo

Apresentar os resultados de uma série de casos de reconstrução do ligamento cruzado posterior (LCP) em dupla banda com o uso dos tendões flexores autólogos, com seguimento mínimo de dois anos.

Métodos

Avaliação de 16 casos de lesão do LCP submetidos a reconstrução em dupla banda com tendões flexores autólogos entre 2011 e 2013. A amostra final foi composta por 16 pacientes, 15 homens e uma mulher, com média de 31 anos (21-49). O mecanismo predominante foi acidente motociclístico em metade dos casos. Houve um intervalo médio de 15 meses entre a lesão e a cirurgia (três a 52 meses). Cinco lesões eram isoladas e 11, associadas. Foram feitas avaliação clínica, aplicação de escores validados e mensuração com uso do artrômetro KT-1000.

Resultados

A avaliação pela escala de Lysholm pré-operatória teve média de 55 pontos (28-87), evoluiu para uma média pós-operatória de 94 pontos (85-100). O IKDC também demonstrou melhoria. Na avaliação pré-operatória, quatro e 12 pacientes foram respectivamente classificados como C (anormal) e D (muito anormal); na avaliação pós-operatória, seis foram classificados como A (normal) e dez como B (próximo ao normal). Na avaliação pós-operatória pelo artrômetro KT1000, 13 pacientes apresentaram diferença entre 0-2 mm e três, entre 3-5 mm, na comparação com o lado contralateral.

Conclusão

O uso dos tendões flexores autólogos é uma opção viável na reconstrução do LCP em dupla banda, apresenta bons resultados clínicos em seguimento mínimo de dois anos.

Palavras-chave: Joelho/cirurgia, Ligamento cruzado posterior, Traumatismos do joelho, Avaliação dos resultados de intervenções terapêuticas

Introduction

Reconstructions of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are a challenge to the knee surgeon. The frequently associated injuries and difficulties of the reconstructive procedure lead to difficult to achieve and often inferior results when compared to anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions.1 The main discussions regarding this treatment refer to graft options and reconstruction with single or double bundle.

The flexor tendons have been shown to be a very useful tool in the reproduction of the PCL's biomechanical properties. Such grafts have the advantages of ready availability without the need of a tissue bank, no aggression to the extensor mechanism, low morbidity in the donor area, and the grafts easy passage through the bone tunnels, in addition to complete filling of tunnels, favoring integration and stability.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Moreover, it is possible to remove tendons from both knees and increase the final thickness, with greater resemblance to the original PCL.

Another question concerns the reconstruction of the PCL with a single femoral tunnel or double-bundle, the latter being an attempt to more effectively reproduce the original anatomy of the ligament. By creating two femoral tunnels, the knee surgeon aims to maintain the biomechanical properties of the PCL. Recent studies have demonstrated the superiority of this technique in terms of knee stability, despite the greater complexity of the procedure.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

The objective of the present study is to present the results of a series of cases of double-bundle PCL reconstruction using autologous flexor tendons of both knees, with a minimum follow-up of two years.

Patients and methods

The study included cases of isolated grade 2 or 3 PCL ruptures that were symptomatic after conservative treatment or were associated with other injuries, treated between 2011 and 2013. Skeletally mature patients, with no age limit, and with no previous injuries and/or surgical treatment in the knee were included. The final analysis included 16 patients, 15 men and one woman. The mean patient age was 31 years (21–49); the main mechanism was motorcycle accident in eight patients, automobile accident in four, and sports injury in four. The mean interval between injury and surgery was 15 months (3–52).

Five patients had isolated PCL involvement and 11 presented associated ligament damage. Table 1 summarizes the associated lesions.

Table 1.

Frequency of ligament injuries.

| Quantity | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated PCL injuries | 5 | 31.25 |

| Combined injuries | 11 | 68.75 |

| PCL + PC | 6 | 37.5 |

| PCL + ACL | 3 | 18.75 |

| PCL + MCL | 2 | 12.5 |

| Total | 16 | 100 |

PC, posterolateral corner; ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; MCL, medial collateral ligament; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament.

Observation: Of the patients with combined injuries, five had a chondral injury (31.25%) and one had a lateral meniscal injury (6.25%).

Those who did not meet the criteria mentioned, with clinical and/or radiographic signs of osteoarthrosis or bone injuries (fractures) in the knee region, were excluded.

Patients underwent preoperative evaluation including physical examination and application of the Lysholm15 and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores. The following imaging examinations were used: orthostatic X-rays of both knees in anteroposterior and lateral views, axial view of the patella, panoramic X-ray of the lower limbs, and magnetic resonance of the affected knee.

The surgical procedure was always performed by the same surgeon, after physical examination under sedation that clinically documented the observed lesions. The flexor tendons (semitendinosus and gracilis) were removed from both limbs and were prepared and measured by an assistant surgeon.

To reconstruct isolated PCL injuries the transtibial technique was used to reconstruct isolated PCL injuries, with the flexor tendons divided as follows: two semitendinosus tendon grafts reserved for the reconstruction of the anterolateral (AL) bundle and two gracilis grafts for the posteromedial (PM) bundle. This strategy aimed to ensure a satisfactory thickness of the reconstructed ligament. A mean size of 9–10 mm was achieved with the association of semitendinosus grafts and of 8–9 mm with gracilis grafts; these values comprise the mean thickness of each bundle and its respective femoral tunnel.

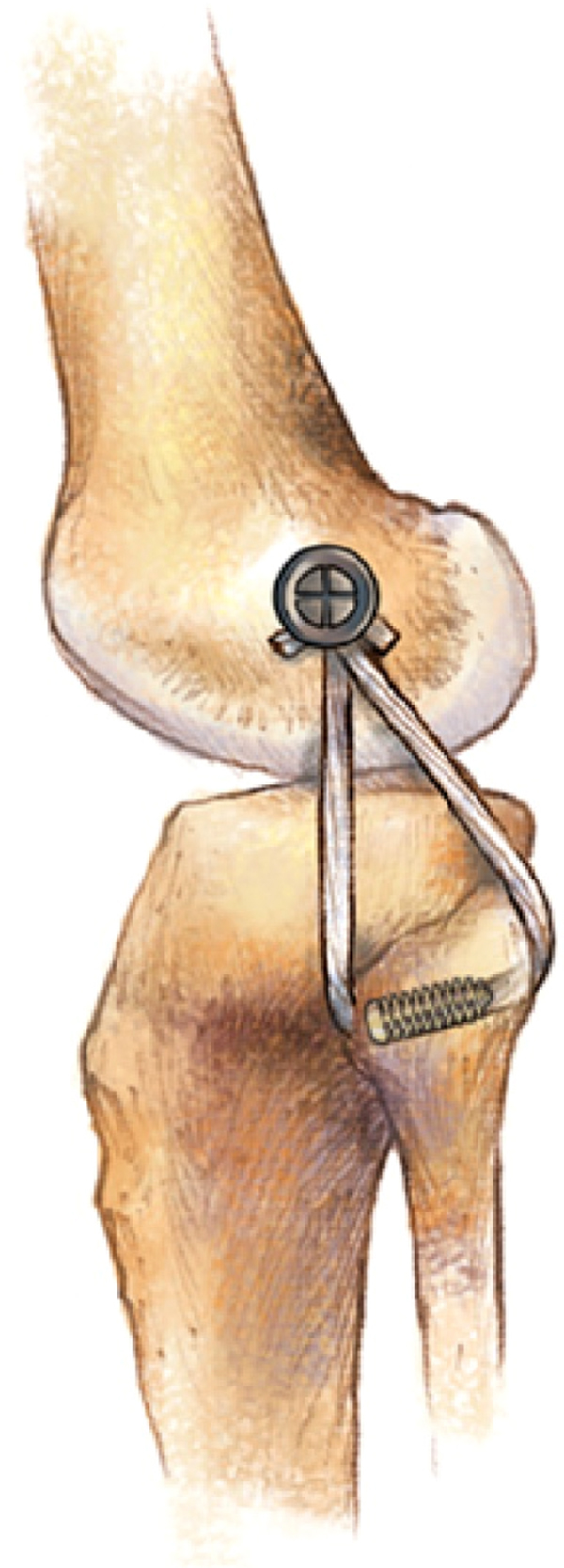

In cases of associated peripheral injury, a single semitendinosus tendon was used for reconstruction. In these situations, the PCL treatment strategy was modified: the remnant semitendinosus tendon associated with one gracilis was reserved for AL bundle reconstruction, and a single gracilis muscle graft was reserved for the PM bundle. The Fanelli technique was the choice for injuries of the posterolateral region.16 ACL-associated injuries were reconstructed in a second moment, using the central third of the patellar tendon of the injured knee. Injuries of the medial collateral ligament were treated conservatively.

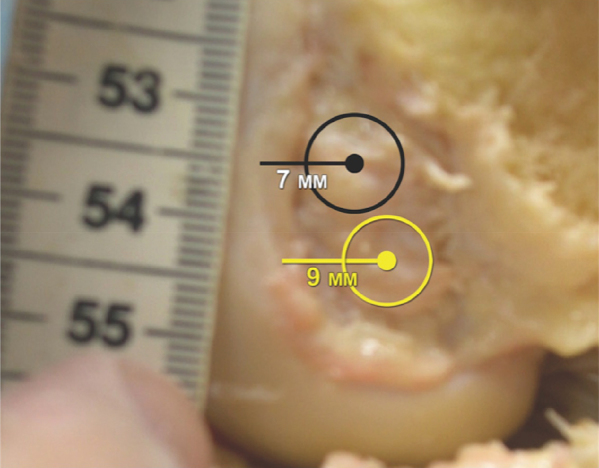

The arthroscopic stage of the surgery was initiated by careful joint inspection; meniscal and chondral lesions were documented and treated. Then, the injured ligament was debrided and the distal bed of the PCL was prepared through an accessory posteromedial portal. The creation of the tibial tunnels began with the use of an appropriate guide and fluoroscopic control of the wire passage to minimize the risk of vascular injury. The chosen site was the center of the PCL footprint in the anteroposterior view, placed in the midpoint of the lower half of the PCL facet in the lateral view. Femoral tunnels were created with the help of an outside-in guide, respecting the anatomical position of the PCL; the center of the AL and PM bundles to the articular cartilage measured 7 and 9 mm, respectively.

After the grafts were passed, a single tibial fixation was carried out. The AL bundle was fixated first in the femur, tensioned at 90 degrees of flexion. Subsequently, the knee was extended and the PM bundle was fixated in full extension. In all tunnels (femoral and tibial), the fixation was achieved with absorbable interference screws (Arthrex®, Naples, FL, USA). Fig. 1, Fig. 2 show the sites where the tunnels were made in the tibia and femur for PCL reconstruction, while Fig. 3 shows the process of reconstruction of the posterolateral corner. Fig. 4 shows the appearance of the PCL reconstruction in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

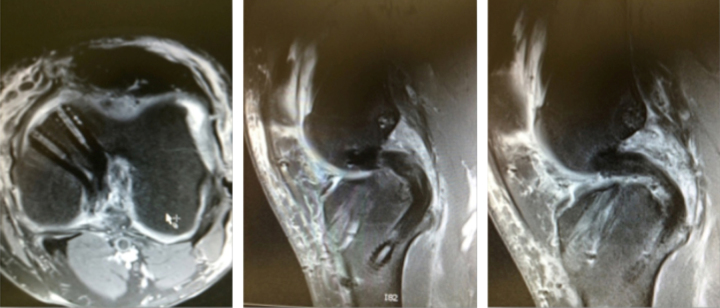

Fig. 1.

Insertion sequence and proper guidewire position for tibial tunnel reaming in PCL reconstruction.

Fig. 2.

Femoral tunnel reaming sites in the medial femoral condyle in PCL reconstruction, showing the distance of each tunnel in relation to the border of the distal cartilage (in black, AL bundle and in yellow, PM bundle).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the technique used for posterolateral corner reconstruction.

Source: Fanelli GC.16

Fig. 4.

Aspect of PCL reconstruction at the magnetic resonance imaging, evidencing the double tunnel in the femur and the single tunnel in the tibia.

After the procedure, the patients underwent a standardized rehabilitation protocol.17

In the postoperative period, the final assessment was made at a minimum follow-up of two years, when a opposite limb comparative physical examination was performed. The tibial posteriorization was measured using the KT-1000, and the IKDC and Lysholm scores were again applied. Both preoperative and postoperative assessments were performed by three of the authors.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee under CAAE No. 15810213.3.0000.5479.

Results

When assessing the scores, a mean preoperative Lysholm of 55 points (poor) was observed, ranging from 28 to 87. In the postoperative evaluation, there was a significant score improvement, with a mean of 94 points (excellent), ranging from 85 to 100. When separating isolated PCL injuries and associated injuries, the postoperative analysis demonstrated a considerable numerical similarity. In patients with isolated PCL involvement, a mean progression from 63.6 to 94.6 was observed. In patients in whom the posterolateral corner was also involved (six cases), the mean progression went from 52.75 to 94; in cases of PCL and ACL injuries (three cases) were from 63.6 to 94.6. Finally, in patients with PCL associated with medial collateral ligament injuries (two cases), from 40.5 to 95. These results highlight the lower subjective preoperative evaluation of the patients with associated peripheral injury, both in the posterolateral corner and the medial compartment.

In the preoperative period, 12 cases were classified as D in the IKCD score, and four as C. Improvement was observed in the postoperative period, with six cases classified as A and ten as B. In an individualized analysis of these results, again comparing isolated injuries with associated ones, a lower preoperative IKDC score was observed in injuries of the central and peripheral axis. All six cases with posterolateral corner involvement were classified as D in the preoperative period; of these, four were classified as B and two as A in the postoperative period. The two cases with medial collateral ligament injury evolved from D to A. In combined injuries of the PCL and LCA, two cases progressed from C to A and one case from D to B. In isolated injuries, 60% (three out of five) were classified as C in the preoperative period, while the other two were classified as D. In the postoperative period, all isolated injuries were classified as B by the IKDC, due to patellofemoral crepitus and range of motion deficits. Table 2 summarizes the IKDC findings.

Table 2.

Pre- and postoperative IKDC.

| Isolated IKDC lesions | Preoperative period | Postoperative period | Complex IKDC lesions | Preoperative period | Postoperative period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 0 | A | 0 | 6 (54.5%) |

| B | 0 | 5 (100%) | B | 0 | 5 (45.5%) |

| C | 3 (60%) | 0 | C | 2 (18.2%) | 0 |

| D | 2 (40%) | 0 | D | 9 (81.8%) | 0 |

| Total | 5 (31.25%) | Total | 11 (68.75%) | ||

| Total | 16 (100%) | ||||

In the postoperative analysis using the KT-1000 arthrometer, the difference ranged from 0 to 2 mm in 13 cases and from 3 to 5 mm in three.

The reverse pivot-shift test was performed, and the external tibial rotation was measured by dial test at 30 and 90 degrees. No case was positive, and the remaining external tibial rotation was less than 5 degrees in all cases operated. The postoperative range of motion was similar to the non-operated limb in all cases. Mild patellofemoral crepitus was observed in six cases. No significant muscle atrophy was observed in the operated patients. There were no complaints of pain related to graft removal.

Discussion

Effectively reproducing the biomechanical properties of PCL is challenging, given the biomechanical characteristics and forces acting on this graft, in addition to the lower incidence of injuries, which makes the learning curve steeper.

The use of the flexor tendons is a very functional alternative, with good results documented in the literature. In the 1990s, Pinczewski et al.18 presented a series of 40 cases of PCL reconstructions using flexor tendons. At that time, Shino et al.19 published a technique that used the semitendinosus/gracilis for single bundle reconstruction, but with suspensory fixation; both presented satisfactory results.

The present study has a new feature in relation to the previous literature: reconstruction utilizing a double bundle with autologous graft of the flexor tendons, removed from both limbs. This option represents the evolution of a line of research by the authors in the reconstructions of the PCL. The authors believe that this technique, albeit more demanding from a technical standpoint, reproduces more effectively the posterior stabilization of the knee. The double bundle, which in the past lacked better quality studies in relation to the methodology employed, has had its superiority demonstrated in recent studies. In a recent meta-analysis that included 435 patients, Zhao et al.20 observed that double-bundle reconstruction was superior to the single-bundle technique in isolated PCL injuries when knee stability was measured at 90 degrees of flexion.

The literature also features the comparison of different grafts. Chen et al.21 made a comparative analysis of the use of the flexor tendons and quadriceps tendon, both autologous. A total of 54 patients were assessed and the authors concluded that both grafts were satisfactory. A comparative analysis between the use of the Achilles tendon and the semitendinous/gracilis tendons was retrieved in the literature. Ahn et al.1 randomized 36 patients between the aforementioned grafts. Those authors found similar results with both techniques, noting that the smaller length and diameter of the flexor tendons did not interfere in the results.

Although a comparative analysis of the grafts was not included, the present authors have published a series on the use of the quadricipital tendon associated with the semitendinosus.22, 23 The authors list the following as advantages of the use of the flexor tendons: the nonaggression to extensor mechanism, which enhances rehabilitation and reduces postoperative morbidity; greater ease in passing the graft through the bone tunnels; the completion of the tunnels; and the possibility of fixation with interference screws directly into the graft, without interfaces. The authors believe that this biomechanical aspect of the fixation can add stability to the reconstruction, since the post screw fixation used for the quadricipital tendon, considered biomechanically inferior, is no longer necessary. The present results corroborate these hypotheses, since in 81% of the cases there was no difference in posterior stability with the knee at 90 degrees in the KT-1000 analysis.

In the present study, it was not possible to clearly establish any factors that could determine a worse or better prognosis after ligament reconstruction (gender, age, and trauma mechanism, among others). Nonetheless, it was observed that cases with associated injuries, in which the instability prior to surgery was more pronounced than in the isolated cases, benefited the most from the surgical procedure, as assessed by the greater variation of the scores between the pre- and postoperative period. Patellofemoral crepitus was observed in cases with lower postoperative score (both in Lysholm and IKDC); the authors believe that it is related to direct trauma in the anterior region of the knee and can lead to pain and/or discomfort even in the presence of a stable knee. This factor, however, was present both in cases of isolated and combined lesions.

An important question related to bilateral removal of the flexor tendon involves intervention in the healthy limb. From a technical standpoint, the removal of all tendons is necessary, aiming at a more exact reproduction of the natural dimensions of the PCL, since it is believed that graft thickness plays an important role in the final stability. In the present study, no major clinical complaints related to the donor site were registered. Moreover, no patellofemoral crepitus or significant muscular atrophy were observed. This information is in agreement with the literature. Yasuda et al.24 analyzed the aspects of morbidity in 65 cases of ACL injuries that underwent removal of the flexor tendons. The authors found minimal complaints related to donor site. Muscle strength was also measured; the alterations observed resolved in approximately one year. The authors conclude that flexor tendons are a satisfactory option, with minimal associated morbidity.

The information presented in this article is of extreme importance considering the reality of most orthopedic services in developing countries, where access to a tissue bank is still lacking and costly.

The limitations of the present study are the small number of patients, the lack of a control group, and the inclusion of isolated and combined lesions in the same sample.

Conclusion

The use of flexor tendon autograft is a viable option in the reconstruction of the PCL using a double bundle, presenting good clinical results in a two-year follow-up. This technique has low rates of complications and morbidity in the graft donor site.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (FCMSCSP), Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia, Grupo de Cirurgia do Joelho, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

References

- 1.Ahn J.H., Yoo J.C., Wang J.H. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: double-loop hamstring tendon autograft versus Achilles tendon allograft – clinical results of a minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(8):965–969. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullis D.W., Paulos L.E. Reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament with allograft. Clin Sports Med. 1994;13(3):581–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indelicato P.A., Bittar E.S., Prevot T.J., Woods G.A., Branch T.P., Huegel M. Clinical comparison of freeze-dried and fresh frozen patellar tendon allografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(4):335–342. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemzek J.A., Arnoczky S.P., Swenson C.L. Retroviral transmission in bone allotransplantation. The effects of tissue processing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(324):275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson D.W., Grood E.S., Arnoczky S.P., Butler D.L., Simon T.M. Freeze dried anterior cruciate ligament allografts. Preliminary studies in a goat model. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(4):295–303. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Defrere J., Franckart A. Freeze-dried fascia lata allografts in the reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament defects. A two- to seven-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(303):56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harner C.D., Janaushek M.A., Kanamori A., Yagi M., Vogrin T.M., Woo S.L. Biomechanical analysis of a double-bandle posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(2):144–151. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Race A., Amis A.A. PCL reconstruction. In vitro biomechanical comparison of isometric versus single and double-bundled ‘anatomic’ grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):173–179. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b1.7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda K., Kitamura N., Kondo E., Hayashi R., Inoue M. One-stage anatomic double-bundle anterior and posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the autogenous hamstring tendons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(7):800–805. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0800-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyland J., Hester P., Caborn D.N. Double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with allograft tissue: 2-year postoperative outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10(5):274–279. doi: 10.1007/s00167-002-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borden P.S., Nyland J.A., Caborn D.N. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (double bundle) using anterior tibialis tendon allograft. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(4):E14. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.23425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C.H., Chen W.J., Shih C.H. Arthroscopic double-bundled posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with quadriceps tendon-patellar bone autograft. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(7):780–782. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markolf K.L., Feeley B.T., Jackson S.R., McAllister D.R. Biomechanical studies of double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1788–1794. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shon O.J., Lee D.C., Park C.H., Kim W.H., Jung K.A. A comparison of arthroscopically assisted single and double bundle tibial inlay reconstruction for isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):76–84. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peccin M.S., Ciconelli R., Cohen M. Questionário específico para sintomas do joelho Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale: tradução e validação para a língua portuguesa. Acta Ortop Bras. 2006;14(5):268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fanelli G.C. Fibular head-based posterolateral reconstruction of the knee: surgical technique and oucomes. J Knee Surg. 2015;28(6):455–463. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1564594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cury R.P.L., Kiyomoto H.D., Rosal G.F., Bryk F.F., Oliveira V.M., Camargo O.P.A. Protocolo de reabilitação para as reconstruções isoladas do ligamento cruzado posterior. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;47(4):421–427. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30122-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinczewski L.A., Thuresson P., Otto D.D., Nyquist F. Arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using four strand hamstring tendon graft and interference screws. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(5):661–665. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shino K., Nakagawa S., Nakamura N., Matsumoto N., Toritsuka Y., Natsu-ume T. Arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring tendons: one-incision technique with Endobutton. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(5):638–642. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J.X., Zhang L.H., Mao Z., Zhang L.C., Zhao Z., Su X.Y. Outcome of posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the single- versus double bundle technique: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2015;43(2):149–160. doi: 10.1177/0300060514564474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C.H., Chen W.J., Shih C.H. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament: a comparison of quadriceps tendon autograft and quadruple hamstring tendon graft. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(6):603–612. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.32208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cury R.P., Severino N.R., Camargo O.P.A., Aihara T., Oliveira V.M., Avakian R. Reconstrução do ligamento cruzado posterior com enxerto autólogo do tendão do músculo semitendinoso duplo e do terço médio do tendão do quadríceps em duplo túnel no fêmur e único na tíbia: resultados clínicos em dois anos de seguimento. Rev Bras Ortop. 2012;47(1):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cury R.P.L.C., Mestriner M.B., Kaleka C.C., Severino N.R., Oliveira V.M., Camargo O.P. Double-bundle PCL reconstruction using autogenous quadriceps tendon and semitendinous graft: surgical technique with 2-year follow-up clinical results. Knee. 2014;21(3):763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yasuda K., Tsujino J., Ohkoshi Y., Tanabe Y., Kaneda K. Graft site morbidity with autogenous semitendinosus and gracilis tendons. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(6):706–714. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]