Abstract

Objective

To present a retrospective study of 16 patients submitted to hip disarticulation.

Methods

During the period of 16 years, 16 patients who underwent hip disarticulation were identified. All of them were studied based on clinical records regarding the gender, age at surgery, disarticulation cause, postoperative complications, mortality rates and functional status after hip disarticulation.

Results

Hip disarticulation was performed electively in most cases and urgently in only three cases. The indications had the following origins: infection (n = 6), tumor (n = 6), trauma (n = 3), and ischemia (n = 2). The mean post-surgery survival was 200.5 days. The survival rates were 6875% after six months, 5625% after one year, and 50% after three years. The mortality rates were higher in disarticulations with traumatic (66.7%) and tumoral (60%) causes. Regarding the eight patients who survived, half of them ambulate with crutches and without prosthesis, 25% walk with limb prosthesis, and 25% are bedridden. Complications and mortality were higher in the cases of urgent surgery, and in those with traumatic and tumoral causes.

Conclusion

Hip disarticulation is a major ablative surgery with obvious implications for limb functionality, as well as high rates of complications and mortality. However, when performed at the correct time and with proper indication, this procedure can be life-saving and can ensure the return to the home environment with a certain degree of quality of life.

Keywords: Hip joint, Disarticulation, Amputation, Lower extremity, Infection, Tumor

Resumo

Objetivo

Apresentar um estudo retrospectivo em 16 pacientes submetidos a desarticulação da anca.

Métodos

Foram identificados 16 pacientes submetidos a desarticulação da anca ao longo de 16 anos. Todos foram estudados por meio dos registos clínicos quanto a sexo, idade na cirurgia, causa da desarticulação, complicações no pós-operatório, índices de mortalidade e grau de funcionalidade após a desarticulação da anca.

Resultados

A desarticulação da anca foi feita eletivamente na maioria das situações e apenas de forma urgente em três casos. As indicações tiveram as seguintes origens: infecção (n = 6), tumor (n = 5), traumatismo (n = 3) e isquemia (n = 2). O tempo médio global de sobrevivência pós-cirurgia foi de 200,5 dias. Os índices de sobrevivência foram de 68,75% após seis meses, 56,25% após um ano e de 50% após três anos. Os índices de mortalidade foram mais elevados nas desarticulações de causa traumática (66,7%) e de causa tumoral (60%). Em relação aos oito pacientes que permanecem vivos, metade faz marcha com apoio de muletas canadenses e sem prótese, 25% fazem marcha com membro protético e 25% encontram-se acamados. As taxas de complicações e mortalidade foram mais elevadas nas desarticulações urgentes e nas efetuadas em consequência de traumatismos e tumores.

Conclusão

A desarticulação da anca é uma cirurgia altamente mutilante, com implicações óbvias na funcionalidade do membro e taxas elevadas de complicações e mortalidade. No entanto, quando efetuado em um momento adequado e com indicação correta, esse procedimento pode salvar a vida do paciente e garantir o seu regresso ao domicílio com alguma qualidade de vida.

Palavras-chave: Articulação da anca, Desarticulação, Amputação, Extremidade inferior, Infeção, Tumor

Introduction

Hip disarticulation is the amputation of the lower limb through the hip joint; it continues to be one of the most radical procedures in orthopedic surgery.1, 2 This surgery accounts only for approximately 0.5% of lower limb amputations.1 The most frequent indications are highly invasive tumors of the musculoskeletal system that are unresectable with limb conservation, limb ischemia, trauma, and severe musculoskeletal infections of the pelvic region and/or groin.1

Material and methods

The authors present a series of 16 patients who underwent hip disarticulation over a period of 16 years (1999–2015) at this institution, which includes centers dedicated to tumors and septic pathology of the musculoskeletal system. All patients were characterized and studied retrospectively through clinical records regarding gender, age at surgery, cause of disarticulation, postoperative complications, mortality rates, and degree of functionality after hip disarticulation. The variables were analyzed using SPSS, version 23, and a 0.05 significance level was adopted. Quantitative values were presented as mean, minimum value, maximum value, and standard deviation, while qualitative values were described as number (n) and percentage (%). For the comparisons of qualitative variables between groups, the chi-squared test was used, while the Mann–Whitney test was used for quantitative variables. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, and all patients or their respective families signed an informed consent form.

Results

Sample comprised of 16 patients, nine males and seven females, with a mean age of 61.25 years (29–87). Disarticulation surgery was performed according to the techniques described in the literature.3, 4 After isolating and ligating the femoral neurovascular bundle, the hip muscles were cut to the level of the femoral head, which was separated from the acetabulum.

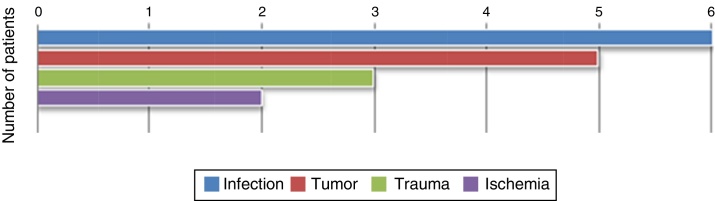

Hip disarticulation was performed electively in most situations; only three cases required emergency surgery. Indications for hip disarticulations were infection (n = 6), tumor (n = 5), trauma (n = 3), and ischemia (n = 2) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). For elective surgeries, hemoglobin reduction between the preoperative and immediate postoperative periods (mean 3.37, range: 0.7–4.3) was used to assess intraoperative blood losses.

Fig. 1.

Reasons for hip disarticulation.

Table 1.

Description of the series of hip disarticulations.

| Cause | Frequency (number) | Frequency (percentage) | Urgent dislocations (percentage) | Mean post-surgery survival in patients who died (days) | Mortality (percentage) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | 6 | 37.50 | 0 | 171.5 | 33.33 | 33.33 |

| Tumor | 5 | 31.25 | 0 | 416 | 60 | 60 |

| Trauma | 3 | 18.75 | 66.67 | 3 | 66.67 | 33.33 |

| Ischemia | 2 | 12.50 | 50 | 7 | 50 | 50 |

Large reconstructive prostheses were the most common cause of disarticulation due to infection (66.67% of the cases). The remaining cases of infection occurred in ischemic and necrotic contexts. The most frequently detected microorganism was Staphylococcus aureus (n = 3), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 2) and Enterococcus faecium (n = 2). Infections were mostly monomicrobial; only one case had polymicrobial infection. Tumors found as a cause of hip disarticulation were chondrosarcoma (n = 3), pleomorphic sarcoma of the thigh (n = 2), and basal cell tumors (n = 1).

The three polytraumatized patients in this series had extensive slough in the pelvis and thigh, with multi-organ injuries and need for multidisciplinary treatment. All of them showed hemodynamic instability and only one survived past the first postoperative week. The causes of ischemia verified in the sample were acute arterial ischemia due to femoral arterial thromboembolism and iatrogenic lesion of the common femoral artery. In three patients, one with traumatic lesion and two with ischemic lesions, a supracondylar amputation of the femur was initially performed, which, due to unfavorable evolution and superinfection, led to the need for hip disarticulation. Complications were observed postoperatively in seven patients (43.75%), mainly superficial infections (n = 5), suture dehiscence (n = 2), necrosis of the amputation stump scar (n = 2), and metastasis of the amputation stump (n = 1). Complications were more commonly observed in disarticulations due to tumors (60%), which corresponds to the group with the longest post-surgical survival time (416 days). A trend for higher rates of complications in emergency surgeries when compared with elective (66.67% vs. 38.50%) was observed, but without statistical significance (p = 0.55). A higher complication rate in individuals who underwent surgery prior to disarticulation was not observed.

Mean overall post-surgical survival time was 200.5 days; when this manuscript was drafted, only half of the patients in the sample were alive. Survival rates were 68.75% after six months, 56.25% after one year, and 50% after three years. Mortality rates were higher in disarticulations due to trauma (66.7%) and tumor (60%). For the eight patients who had died when this review was drafted, there was a tendency for lower survival time in those who underwent emergency surgery (4.33 ± 3.79 days) when compared with elective surgery (318.20 ± 318.01 days), but without statistical significance (p = 0.14). In patients who are alive, the most common reason for disarticulation was infection (50%), followed by tumor (25%); there was only one case of ischemia and one case of trauma.

Mean life expectancy of those who survived for more than three months after surgery was 205.5 days for bedridden patients and 588 days for those who were able to walk. Half of the patients walk with crutches without prosthesis due to intolerance to it, 25% walk with prosthetic limbs, and 25% are bedridden. In the six patients who are able to walk, the most frequent reason for disarticulation was infection (50%), followed by tumor (33.33%). All these patients have frequent events of phantom pain requiring medical treatment.

Discussion

Hip disarticulation is a complex and infrequent surgery, only performed as the last option in extreme cases.1, 5 The literature on this surgery is scarce, mainly in the form of case reports and small series.5 A review of the most relevant articles related to hip dislocations is presented below.

Endean et al.6 analyzed a series of 53 hip dislocations performed over 24 years; indications included tumors (n = 17), ischemia associated with infection (n = 14), infection (n = 12), and ischemia (n = 10). The predominant types of tumors were sarcomas, more often liposarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and fibrous histiocytoma. The infection group comprised eight severe soft tissue infections, three pressure sores, and three cases of femoral osteomyelitis. Patients in the ischemic group had peripheral vascular disease, and six of them were previously submitted to revascularization surgeries. In the ischemia associated with infection group, all patients were previously submitted to revascularization surgeries, as well as distal limb amputations. Those authors observed a rate of operative wound complications of 60%, being more frequent in the group of ischemia associated with infection (in 83%). Most common types were infections and necrosis of the surgical wound. Mean mortality was 21%, ranging from 0% in those caused by tumor to 50% in those caused by ischemia. A statistically significant association was observed between previous supracondylar amputation, urgent surgery, and surgical wound complication index. Moreover, mortality rate was significantly higher in urgent surgeries (33%) when compared with elective surgeries (4%). Presence of ischemia associated with limb infection and heart disease was the greatest predictor of mortality. Dénes and Till7 analyzed a series of 63 dislocations, whose indications were arterial ischemia (n = 34), tumor (n = 24), and infection (n = 4). Surgical wound complications were observed in 64.86% of the patients whose disarticulation had vascular cause and in 20.83% of those with tumor cause. The mortality rate in the first postoperative month ranged from 43.24% in those with a vascular cause to 0% in those caused by tumor. All patients who underwent disarticulation due to a tumor were able to walk with a prosthetic limb; in contrast, of those whose etiology was vascular, only two used prostheses and 19 became wheelchair-dependent. Unruh et al.8 presented a series of 38 hip dislocations over 11 years of experience. Four patients were disarticulated bilaterally and 20 of the disarticulations occurred in a previously amputated limb, 13 of them during the same hospitalization period. Indications for disarticulations were ischemia secondary to atherosclerosis (n = 17), femoral osteomyelitis (n = 10), and trauma (n = 11). The authors reported post-operative infections (63%) as the most frequent complication. In the postoperative period, septic shock (21%), hemorrhagic shock (11%), disseminated coagulopathy (11%), acute renal failure (24%), and cardiac (26%) and pulmonary (24%) dysfunctions were observed. Mean mortality rate was 44%: 60% in cases of ischemia associated with infection, 20% in cases of ischemia without infection, 22% in cases of femoral osteomyelitis, 100% in cases of trauma associated with infection, and 33% in cases of trauma without infection. Those authors stated that the presence of preoperative infection tripled the risk of death after hip disarticulation. Regarding functionality, they observed that none of the 19 survivors were able to use the prosthetic limb, only four were able to walk with a walker, 12 were wheelchair-dependent, and three were bedridden. Fenelon et al.9 presented a series of 11 disarticulations secondary to infection complications of hip arthroplasty. Indications for disarticulation were severe fistulizing soft tissue and femur infections, one case of pronounced femoral bone loss, and one case of ruptured false aneurysm of the external iliac artery. Disarticulation was urgent in six cases and elective in the remainder; no deaths were observed in the perioperative period. The most commonly found microorganisms were Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, and Proteus; 81.82% of the disarticulated patients had already undergone four or more hip arthroplasty revision surgeries. The authors suggest that some dislocations could have been avoided if a resection arthroplasty had been performed instead of repeated prosthesis revisions. Assessing the functional results of the eight survivors at the time of the review, six patients were able to walk, four with walkers and two with prosthetic limbs, and two were bedridden. There were also three cases of surgical wound complications and two cases of phantom pain. László and Kullmann10 studied 29 hip dislocations of ischemic origin and also found a high rate of surgical wound complications. Healing by first intention only occurred in two cases; scarring by second intention with superficial necrosis was observed in 13 cases, and there were 12 cases of deep necrosis. The mortality rate in the perioperative period was 37%. Only two patients regularly used the prosthetic limb. It was observed that the mortality rate was higher when patients had undergone previous distal amputations. Most of the patients had undergone a mean of 2.3 prior distal amputations and 2.9 conservative limb surgeries. These authors concluded that surgical aggression increases the risk of mortality and that amputation must first be performed at the appropriate level, so as not to subject the patient to several surgeries. Another study of 15 dislocations due to infection, seven due to necrotizing infections and eight due to persistent infections of the proximal thigh, indicated that the most common pathogen was Staphylococcus aureus, present in eight patients.5 Surgeries were elective in eight patients and emergencies in seven. All patients survived surgery; only one death was recorded, on the 29th day after disarticulation.5 The authors concluded that hip disarticulation as treatment of severe infections of the hip and groin can result in high levels of survival, even in cases of emergency surgery, and they attribute these results to multidisciplinary involvement, and to the experience in surgical and post-surgical treatment performed in the intensive care unit at their institution.5 Jain et al.11 studied 80 dislocations, exclusively due to tumor, and found that the predominant histologic types were osteosarcoma (n = 27), chondrosarcoma (n = 8), leiomyosarcoma (n = 8), and liposarcoma (n = 6). In 52.5% of the cases, disarticulation was performed as the first surgery, while in the remainder, surgery was performed due to local recurrence after an attempt of limb-sparing surgery. The five-year survival rate of primary disarticulation was 32%, while for local recurrence it was 25%. There were ten cases of local recurrence after disarticulation with inadequate resection margins. Of the 11 patients who answered the questionnaire about functionality, only one was able to use a prosthetic limb regularly; eight patients reported phantom pain.

In the present sample, we observed that most disarticulations due to infection occurred in the context of patients with large tumor prostheses, which is in agreement with higher risk of these reconstructions to develop infection, not only due to the length and surgery duration, but also to the immunocompromised status of patients.12 Predictably, complications after hip disarticulation are frequent, not only due to the extent of surgery, but also because patients often present extreme situations, with multiple comorbidities and hemodynamic instability. The literature presents controversial results on mortality after hip disarticulation; the rates vary according to the indication, clinical status of the patient, and the degree of urgency of the surgery.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In the present study, it is evident that the best survival rates were observed in elective surgery, particularly in infectious and tumor causes. Conversely, severe polytrauma patients, in emergency situations and often associated with hemodynamic instability, present the worst results in terms of survival and mortality rate. The few studies that analyze functional results after hip disarticulation demonstrated that patients present poor quality of life and significant difficulties in the recovery of the gait and in the use of substitution prosthesis for the lower limb.7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14 The energy expenditure for gait in patients undergoing hip disarticulation increases by 82%, thus the patient is often confined to a wheelchair or bedridden.5, 8, 15 Furthermore, Nowroozi et al.15 indicate that, in disarticulated patients, gait with prosthetic limb leads to a higher energy consumption when compared with gait with crutches. This statement is corroborated by the present study, as half of the survivors walk with crutches without the use of the prosthetic limb, while only 25% can use the prosthesis. Dénes and Till.7 reported that functional success depends on the cause of disarticulation and advocate that, in general, those due to tumor and trauma are better suited to gait than those due to vascular conditions. In the present sample, the most common reasons for disarticulation in patients who are currently able to walk were infection and tumors; the only living patient with an ischemic condition is bedridden. Individual motivation, age, overall health status, and comorbidities of the patient are considered to be crucial factors for recovery of gait.11

The limitations of the present study were the small number of individuals in the sample and the fact that it was a retrospective observational study. Larger samples could probably change some of the statistical trends into statistically significant differences.

Conclusions

Hip disarticulation is a highly mutilating and last-resort surgery, with obvious implications for limb functionality and high rates of complications and mortality. However, when performed in the proper time window and with correct indication, it is a life-saving surgery that allows the patient to return home. For the success of this surgical procedure, early identification of hip disarticulation indications is paramount; so as not to postpone an unavoidable situation and consequently aggravate the prognosis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Departamento de Ortopedia, Coimbra, Portugal.

References

- 1.Dillingham T.R., Pezzin L.E., MacKenzie E.J. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the United States. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875–883. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman M.H., Wakelin S.J. Amputation through the hip joint during the pre-anaesthetic era. Clin Anat. 2004;17(1):36–44. doi: 10.1002/ca.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd H.B. Anatomic disarticulation of the hip. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84(3):346–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugarbaker P.H., Chretien P.B. A surgical technique for hip disarticulation. Surgery. 1981;90(3):546–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zalavras C.G., Rigopoulos N., Ahlmann E., Patzakis M.J. Hip disarticulation for severe lower extremity infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(7):1721–1726. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0769-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endean E.D., Schwarcz T.H., Barker D.E., Munfakh N.A., Wilson-Neely R., Hyde G.L. Hip disarticulation: factors affecting outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14(3):398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dénes Z., Till A. Rehabilitation of patients after hip disarticulation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116(8):498–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00387586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unruh T., Fisher D.F., Jr., Unruh T.A., Gottschalk F., Fry R.E., Clagett G.P. Hip disarticulation. An 11-year experience. Arch Surg. 1990;125(6):791–793. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410180117019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenelon G.C., Von Foerster G., Engelbrecht E. Disarticulation of the hip as a result of failed arthroplasty. A series of 11 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62(4):441–446. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B4.7430220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.László G., Kullmann L. Hip disarticulation in peripheral vascular disease. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1987;106(2):126–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00435427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain R., Grimer R.J., Carter S.R., Tillman R.M., Abudu A.A. Outcome after disarticulation of the hip for sarcomas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(9):1025–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graci C., Maccauro G., Muratori F., Spinelli M.S., Rosa M.A., Fabbriciani C. Infection following bone tumor resection and reconstruction with tumoral prostheses: a literature review. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010;23(4):1005–1013. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daigeler A., Lehnhardt M., Khadra A., Hauser J., Steinstraesser L., Langer S. Proximal major limb amputations – a retrospective analysis of 45 oncological cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebrahimzadeh M.H., Kachooei A.R., Soroush M.R., Hasankhani E.G., Razi S., Birjandinejad A. Long-term clinical outcomes of war-related hip disarticulation and transpelvic amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(16):e114. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01160. 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowroozi F., Salvanelli M.L., Gerber L.H. Energy expenditure in hip disarticulation and hemipelvectomy amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64(7):300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]