Abstract

Chromatin looping mediated by the CCCTC binding factor (CTCF) regulates V(D)J recombination at antigen receptor loci. CTCF-mediated looping can influence recombination signal sequence (RSS) accessibility by regulating enhancer activation of germline promoters. CTCF-mediated looping has also been shown to limit directional tracking of the RAG recombinase along chromatin, and to regulate long-distance interactions between RSSs, independent of the RAG recombinase. However, in all prior instances in which CTCF-mediated looping was shown to influence V(D)J recombination, it was not possible to fully resolve the relative contributions to the V(D)J recombination phenotype of changes in accessibility, RAG-tracking, and RAG-independent long-distance interactions. Here, to assess mechanisms by which CTCF-mediated looping can impact V(D)J recombination, we introduced an ectopic CTCF binding element (CBE) immediately downstream of Eδ in the murine Tcra-Tcrd locus. The ectopic CBE impaired inversional rearrangement of Trdv5 in the absence of measurable effects on Trdv5 transcription and chromatin accessibility. The ectopic CBE also limited directional RAG tracking from the Tcrd recombination center, demonstrating that a single CBE can impact the distribution of RAG proteins along chromatin. However, such tracking cannot account for Trdv5-to-Trdd2 inversional rearrangement. Rather, the defect in Trdv5 rearrangement could only be attributed to a reconfigured chromatin loop organization that limited RAG-independent contacts between the Trdv5 and Trdd2 RSSs. We conclude that CTCF can regulate V(D)J recombination by segregating RSSs into distinct loop domains and inhibiting RSS synapsis, independent of any effects on transcription, RSS accessibility and RAG tracking.

Introduction

Adaptive immunity depends on the expression of diverse repertoires of antigen receptors (AgRs3) by T and B lymphocytes. This is achieved by somatic assembly of variable (V), diversity (D) and joining (J) gene segments at AgR loci, a process termed V(D)J recombination (1). V(D)J recombination is initiated by recombination activating gene 1 (RAG1) and RAG2 (collectively referred to as RAG) (2), which can recognize recombination signal sequences (RSSs) that flank each V, D and J gene segment and bring two RSSs into a synaptic complex (3). Within this complex, RAG creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) between RSSs and coding segments. These DSBs are processed and repaired by the non-homologous end joining pathway to form coding joints and signal joints. In developing lymphocytes, RAG binds efficiently and in a developmental stage- and cell lineage-specific manner to discrete, highly transcribed regions of AgR loci containing D or J gene segments, so-called recombination centers (RCs)(4–6). Initial RAG binding to RCs is consistent with the RSS capture model, in which RAG initially engages one RSS and then captures a second RSS to form the synaptic complex (1). Because V gene segments are generally distal to the RC, their capture for V-to-J or V-to-DJ recombination is thought to require conformational changes of AgR loci. Indeed, the Igh, Igκ, Tcrb and Tcra-Tcrd loci all undergo large-scale contraction to reduce the distance between V gene segments and the RC concurrent with V segment rearrangement (7–12).

Over the last decade, data from chromosome conformation capture (3C)-based assays have shown that chromatin loops at AgR loci bring distant segments of DNA into proximity. These loops appear to be highly dynamic and cell-lineage specific, and are thought to fine-tune gene segment utilization during V(D)J recombination (13). One of the main factors involved in chromatin looping genome-wide is CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF). CTCF is a highly conserved, ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that contains 11 zinc-fingers (14) and binds to over 5 × 105 sites in mammalian genomes (15–18). CTCF is particularly enriched at AgR loci and is known to be a critical regulator of AgR loop organization and V(D)J recombination (13). However, as described below, a variety of mechanisms have been invoked to explain how changes in CTCF-mediated looping may impact V(D)J recombination. These include effects on gene segment accessibility, on gene segment proximity, and on RAG tracking along chromatin.

Studies of the Igh locus revealed that mutation of the intergenic control region 1 (IGCR1) CTCF binding elements (CBEs), located between the Igh RC and proximal VH gene segments, led to significantly enhanced usage of proximal VH gene segments (19). This was attributed to hyperactivation and increased accessibility of these VH gene segments by the RC-associated enhancer Eµ, which is normally insulated from proximal VH gene segments because it is segregated into a distinct CTCF-mediated loop domain. Analysis of the Igk locus in mice conditionally deficient in CTCF in developing B cells revealed a proximally biased Vκ repertoire (20). Again, this was attributed to hyperactivation of proximal Vκ gene segments by RC-associated Igk enhancers iEκ and 3’Eκ, which would normally be insulated from these Vκ segments by CTCF-mediated looping. In related studies, elimination of combinations of CBEs located between Vκ and Jκ segments (Sis and Cer) also created proximally biased Vκ repertoires, which were attributed to a more extended locus configuration in addition to hyperactivation of proximal Vκ gene segments (21, 22).

In a study of the Tcrb locus, the Igf2/h19 imprinting control region (H19-ICR), containing four CBEs, was knocked into the interval between the PDβ1-Dβ1Jβ1Cβ1 and PDβ2-Dβ2Jβ2Cβ2 clusters within the Tcrb RC (23). This allele (termed TCR-Ins) exhibited reduced transcription across the Dβ1-Jβ1 region and reduced Dβ1-to-Jβ1 rearrangement, but normal transcription and rearrangement of Dβ2-to-Jβ2 (23). These defects were attributed to insulation by the H19-ICR CBEs, which prevented Eβ from activating PDβ1 and providing accessibility to the Dβ1Jβ1Cβ1 cluster (24). In addition, Vβ usage on the TCR-Ins allele was strongly biased towards Trbv31, which lies downstream of the Tcrb RC, whereas rearrangement of Trbv13, which lies upstream of the RC, was strongly suppressed (23). It was proposed that the intervening H19-ICR disrupted interactions and synapsis between Trbv13 and Dβ2Jβ2 gene segments, but no direct evidence was provided to support this hypothesis (23, 24).

Deletion of critical intergenic CTCF sites (INT1 and INT2) in the Tcra-Tcrd locus resulted in a proximally biased Vδ repertoire (25), a phenotype similar to those described above for IGCR1 deletion from the Igh locus and Sis and Cer deletion from the Igk locus. However, in the case of INT1-INT2 deletion, there were no changes in V gene segment transcription and accessibility, implying that CTCF-mediated looping did not function as an insulator to constrain the influence of the RC-associated Tcrd enhancer (Eδ). Rather, as defined by 3C, CTCF-mediated looping was found to reduce the frequency of long-distance contacts between proximal Vδ and Dδ RSSs.

In contrast to the various examples noted above, absence of CTCF in CD4+CD8+ thymocytes led to a substantial reduction in proximal Vα-to-Jα rearrangements at the Tcra-Tcrd locus (26). In this case, CTCF facilitates rather than suppresses interactions critical for Vα-to-Jα recombination because the interacting gene segments and regulatory elements, including the Tcra enhancer (Eα), the 5’Jα promoter T early alpha (TEA), and proximal Vα promoters, are themselves marked by CBEs rather than being segregated by them. Therefore, CTCF-mediated looping brings these elements into proximity to support their transcriptional activation and recombination.

Recent studies using linear amplification mediated high throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing (LAM-HTGTS) have suggested that RAG initially bound to a pair of RSSs can release one RSS and then track uni-directionally along the DNA to find additional appropriately oriented bona-fide or cryptic RSSs, which can be used for cleavage and joining (27). Such RAG tracking was shown to be confined within CTCF-mediated loop domains. In pro-B cells, RAG tracking from the Igh RC was normally limited by IGCR1, whereas on IGCR1-deleted alleles, RAG tracked further upstream to reach proximal VH gene segments (27). Similarly, in CD4−CD8− thymocytes, RAG tracking from the Tcrd RC was limited by the INT1-INT2 region, and deletion of this region allowed RAG to track further upstream to proximal Vδ gene segments (28). Thus, in each of the loci discussed above, there are several potential mechanisms by which CTCF-mediated loops can restrict or facilitate recombination events, and the extent to which the different mechanisms contribute to dysregulated V(D)J recombination is difficult to evaluate.

Here, we further investigate mechanisms by which CTCF-mediated loops can influence V(D)J recombination in vivo by generating a mouse model in which an ectopic CBE was introduced as a knock-in (KI) immediately downstream of Eδ. The ectopic CBE impaired RAG-mediated DNA-cleavage at the Trdv5 RSS, resulting in defective inversional rearrangement of Trdv5. Notably, this rearrangement defect was not attributed to altered chromatin accessibility of Trdv5. Moreover, although the ectopic CBE was found to limit directional RAG tracking from the Tcrd RC, such tracking cannot account for Trdv5-to-Trdd2 inversional rearrangement. Rather, the defect in Trdv5 rearrangement could only be attributed to a reconfigured chromatin loop organization that limited long-distance interactions between the Trdv5 and Trdd2 RSSs. We conclude that CTCF can regulate V(D)J recombination by segregating RSSs into distinct loop domains and that this segregation can inhibit RSS synapsis, independent of effects on transcription, RSS accessibility and RAG tracking.

Materials and Methods

Generation of CBE KI mice

Homology arms were generated by PCR using Phusion High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific) and were sequenced to confirm PCR fidelity. The long arm extended from nucleotides 1,570,947 to 1,576,373 of NCBI Reference Sequence NT_039614.1 and the short homology arm extended from nucleotides 1,576,382 to 1,577,981 of the same sequence, with the 70 bp Eα-proximal CBE (CCCACTCTGTTGTAGTGTCTTAAGGTAGCCACACGGGGGCAGCAGTACTCCACCAAAAGGCTTTCTCCCT) added to the 3’ end. Homology arms were cloned into the pGKneoF2L2DTA targeting vector, which was linearized and electroporated into the TC1 129S6/SvEvTAc embryonic stem (ES) cell line, as previously described (25). Neomycin resistant ES cell clones were first screened by PCR and then verified by Southern blot. Verified ES cells were microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts, which were then implanted into pseudopregnant C57BL/6J female mice. Chimeric male founder mice were crossed with CMV-Cre transgenic female mice (Jackson Laboratory) to delete the loxP-flanked neor cassette and obtain germline transmission. Gene-targeted mice were bred to eliminate the CMV-Cre transgene and were of mixed C57BL/6 and 129 genetic background. Breeding schemes of Rag-sufficient mice ensured that littermate controls always segregated wild-type strain 129 Tcra-Tcrd alleles. Similarly, Rag2−/− mice with a 129 genetic background were used as controls in experiments analyzing mutant strain 129 Tcra-Tcrd alleles in Rag-deficient mice. All mice were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were sacrifice at 3–4 weeks of age for all experiments.

Cell sorting

Isolation of DN3 and DP thymocytes was performed using reagents and approaches described previously (25).

Real-time PCR

Taqman-based real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays were performed using LightCycler 480 Probes Master (Roche) with the following PCR program: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 48 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 65°C for 30 s. SYBR green real-time qPCR was performed using the QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN) with the following program: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 62°C for 30 s. All PCR reactions were run in duplicate using a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR system (Roche).

TCR gene rearrangement

Genomic DNA was isolated from sorted DN3 and DP thymocytes and Tcrd and Tcra rearrangement was analyzed by either SYBR-Green or Taqman qPCR using primers described previously (25). To detect RSS DSBs by ligation-mediated quantitative PCR (LM-qPCR), genomic DNA from sorted DN3 thymocytes was linker-ligated as described (29, 30) and amplified DSBs were detected by Taqman-based real-time qPCR. Primers and probes were described previously (26) or are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Tcrd germline transcription

RNA was extracted from Rag2−/− and CBE KI Rag2−/− thymocytes using TRIzol reagent and was converted to cDNA using Superscript III and random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). SYBR-Green qPCR was conducted using primers described previously (25).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP samples were prepared from Rag2−/− and CBE KI Rag2−/− thymocytes as described previously (25). Primers for SYBR-Green qPCR are listed in Supplemental Table 1 or were described previously (25). Results for CTCF-ChIP and histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac)-ChIP were expressed as bound/input and then normalized to values for c-Myc and β2-microglobulin (B2m), respectively.

3C

3C assays were performed on Rag2−/− and CBE KI Rag2−/− thymocytes as described previously (25). 3C products were quantified by Taqman-qPCR with Taqman probes and PCR primers described previously (25). To generate control PCR templates, bacterial artificial chromosomes bMQ-440L6 and bMQ-464f17 (Source BioScience) were mixed in equimolar amounts, and were digested and religated. bMQ-440L6 spans proximal Vα and Vδ gene segments from Trav19 to downstream of Trdv2-2, whereas bMQ-464f17 spans from INT1 to the central Jα gene segments. This control template was used to generate standard curves for all 3C–qPCR assays.

LAM-HGTGTS

DN2/3T lymphocytes were generated from adult bone marrow cells in OP9-DL1 cultures as described (31, 32). Genomic DNA was prepared and LAM-HTGTS was performed and analyzed as described previously (27, 28). LAM-HTGTS data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE81351 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE81351).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 6.0 software.

Results

A selective defect in Tcrd rearrangement in CBE KI mice

The complex V(D)J recombination program of the Tcra-Tcrd locus depends in large measure on the distinct properties of its two known enhancer elements, Eδ and Eα. The former, activated in DN thymocytes, stimulates transcription and chromatin accessibility within a 68-kb region encompassing Trdv4, Trdd1, Trdd2, Trdj1, Trdj2 and Trdv5 (33) and is needed for efficient Tcrd rearrangement (34). The latter, activated in DP thymocytes, extends its influence across 500 kbs, interacting with and stimulating transcription from the TEA and multiple Vα promoters (35); it is required for Tcra rearrangement (36). A CBE immediately downstream of Eα is likely to support these Eα functions, because all such functions are impaired in CTCF-depleted thymocytes (26). The limited range of Eδ has been attributed to an intrinsic feature of Eδ, since it could not activate its natural targets Trdd2 and Trdj1 when it was positioned 100 kb distant, in place of Eα (37). However, that manipulation also eliminated the Eα CBE. Because Eδ lacks a nearby CBE both in its endogenous location and on the replacement allele (26, 37), it remained possible that important distinctions between the range and targets of Eδ and Eα could reflect the selective association of Eα with a strong CBE. Therefore, to assess mechanisms by which CTCF-mediated looping can impact V(D)J recombination at the Tcra-Tcrd locus, we generated the CBE KI allele in which the Eα-proximal CBE was knocked into the region immediately downstream of Eδ (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C, 1D). The orientation of the introduced CBE was identical to that in its natural location downstream of Eα. ChIP confirmed that CTCF binds efficiently to the CBE KI site in CD4−CD8− double negative (DN) thymocytes in vivo (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Generation of CBE KI mice.

(A) Positions of gene segments (black rectangles), enhancers (black ovals) and CBEs (while ovals) in the 3’ 300 kb of the Tcra-Tcrd locus. (B) Wild-type 129/SvJ allele (129), targeting construct CBE KI, neomycin-resistant allele CBE KI neor, and neor-deleted allele CBE KI are shown. DT, diphtheria toxin cassette; B, BglII. Arrows above gene segments denote transcriptional orientations. The location of the southern blot probe is indicated. (C) The sequence of the CBE KI and its location relative to Eδ. Binding motifs for CBF, c-Myb, GATA and CTCF are indicated by horizontal lines and gray lettering. (D) Southern blot of BglII digested genomic DNA from wild-type (+/+) and heterozygous CBE KI neor-targeted ES cells (+/CBE KI neor). Data are representative of two experiments. (E) ChIP of CTCF from Rag2−/− DN thymocytes carrying wild-type (WT) or CBE KI Tcra-Tcrd alleles, analyzed by SYBR-Green qPCR; Trdv4 served as a negative control. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 WT and 3 CBE KI samples, with each sample representing a pool of 6–8 mice. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons.

To analyze the influence of the CBE KI on Tcra-Tcrd locus rearrangement, we initially quantified V-to-(Trdd1)-Trdd2-Trdj1 coding joints in genomic DNA samples prepared from DN3 thymocytes. The strain 129 Tcra-Tcrd locus includes 104 V gene segments, some of which are classified as Vδs (38). Several Vδs, including Trdv1, Trdv2-2, Trdv4 and Trdv5, are proximal to and rearrange exclusively to Dδ gene segments; Trdv5 is unique because it is positioned downstream of Cδ in an inverted orientation. More distal Vδ gene segments, including Trav21-dv12, Trav13-4-dv7, Trav6-7-dv9, Trav4-4-dv10, Trav14d-3-dv8, Trav16d-dv11 and the Trav15-dv6 family, tend to rearrange to both Dδ and Jα gene segments and to serve as both Vδs and Vαs (Fig. 2A). Most other V segments are thought to serve exclusively as Vαs. We detected no significant changes in rearrangement for the majority of Vδ and Vα gene segments tested in CBE KI mice. In this regard, we found no evidence that the introduced CBE could synergize with Eδ to extend its influence to upstream Vδ and Vα gene segments in a manner that subverted the normal pattern of Tcrd rearrangement events. However, we found that the frequency of inversional Trdv5 rearrangement was markedly decreased in CBE KI mice (Fig. 2B).

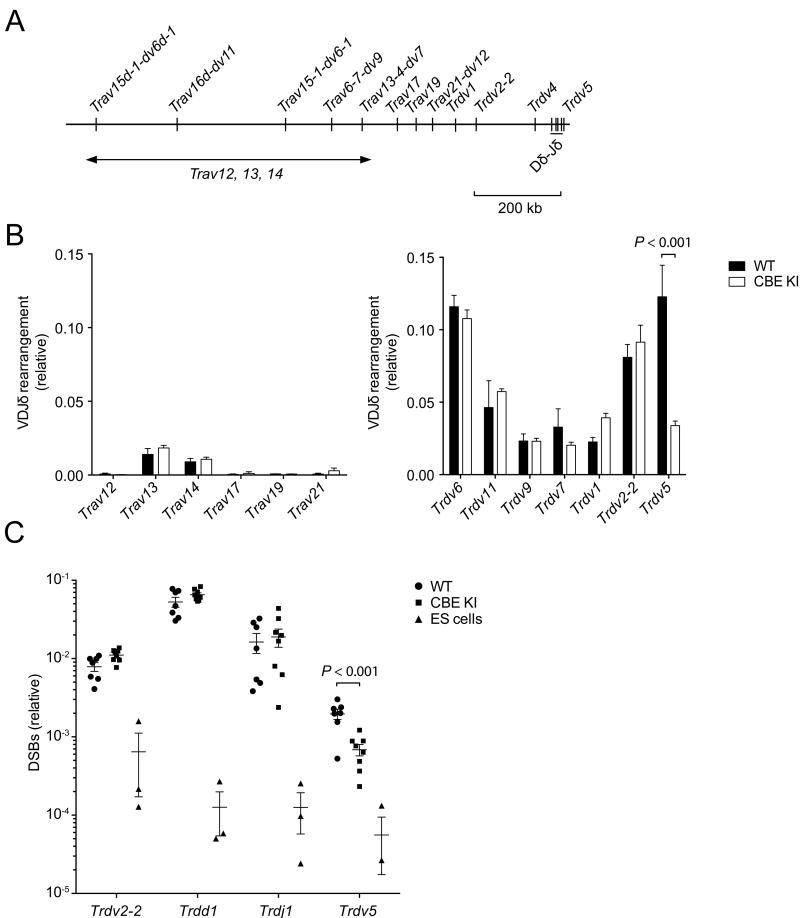

Figure 2. Tcrd rearrangement is perturbed in CBE KI mice.

(A) Locus map identifying Vδ and Vα gene segments analyzed. Trav12, Trav13 and Trav14 are V segment families whose members are distributed across the region indicated. (B) V-(Trdd1)-Trdd2, Trdj1 rearrangements in genomic DNA of DN3 thymocytes sorted from WT and CBE KI mice, analyzed by SYBR-Green (left panel) or Taqman (right panel) qPCR. Data were normalized to Cd14 and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 WT and 3 CBE KI samples, with each sample representing a pool of 3 mice. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. (C) RSS DSBs in genomic DNA of DN3 thymocytes sorted from WT and CBE KI mice, analyzed by LM-qPCR. Embryonic stem (ES) cells served as a negative control. LM-qPCR signals were normalized to those for standard Cd14 genomic PCR. Data represent the mean ± SEM, with each symbol representing an individual mouse. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons.

To confirm that the reduced frequency of Trdv5-(Trdd1)-Trdd2-Trdj1 coding joints reflected a primary defect in Trdv5 recombination, we measured the frequency of DSB V(D)J recombination intermediates by LM-qPCR (29). DSB frequencies were comparable between wild-type and CBE KI DN thymocytes at the 5’ Trdd1 and 5’ Trdj1 RSSs (which contain 12 bp spacers) and at the Trdv2-2 RSS (which contains a 23 bp spacer) (Fig. 2C). However, DSBs at the Trdv5 RSS (which contains a 23 bp spacer) were markedly less frequent in CBE KI as compared to wild-type DN3 thymocytes (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the CBE KI specifically impaired RAG-mediated DNA-cleavage at the Trdv5 RSS.

Since the CBE KI was situated in an intergenic region that would not be deleted by Tcrd rearrangements, it was possible that its introduction into the locus could influence primary Vα-Jα rearrangements. However, we observed no defects in the rearrangement of a range of Vα segments (Trav12, Trav13, Trav17, Trav19 and Trav21) to relatively 5’ Jα segments (Traj61, Traj58, Traj56, Traj49) in CBE KI thymocytes (Fig. 3). We did measure a 50% reduction in Trav12-to-Traj58 rearrangement, but because of the isolated nature of this difference, its biological significance is unclear.

Figure 3. Tcra rearrangement is normal in CBE KI mice.

Vα-Jα rearrangements in genomic DNA extracted from sorted DP thymocytes from WT and CBE KI mice, analyzed by SYBR Green-qPCR. Data were normalized to Cd14 and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 preparations for each genotype, with each preparation representing a different mouse. Statistical significance was evaluated by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

The CBE KI does not perturb chromatin accessibility

We investigated possible mechanisms underlying the defective DNA cleavage at Trdv5 in CBE KI mice. One possibility was that the CBE KI insulates Trdv5 from Eδ, resulting in reduced transcription and chromatin accessibility. We therefore asked whether impaired Trdv5 recombination on CBE KI alleles reflected altered chromatin accessibility of Tcrd gene segments. Because germline transcription is tightly linked to accessibility for V(D)J recombination (39), we analyzed transcription on wild-type and CBE KI alleles with both maintained in germline configuration on a Rag2−/− background. We found no significant differences in germline transcription of Trdv5 or of any other Vδ, Dδ and Jδ gene segments analyzed (Fig. 4A). We also measured histone H3 acetylation (H3Ac) by ChIP (Fig. 4B). We found comparable enrichment of H3Ac at Trdv1, Trdv2-2, Trdd1, Trdd2, Trdj2 and in particular, at Trdv5, on wild-type and CBE KI alleles in DN thymocytes. Trdj1 displayed modestly reduced H3Ac on CBE KI alleles, but this seems an unlikely explanation for a selective defect in Trdv5 rearrangement, since it should affect the rearrangement of all V segments equally. Moreover, this reduction in H3Ac does not appear to influence Trdj1 rearrangement, since we detected no change in DSBs at this site by LM-qPCR (Fig. 2C). We did not examine histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation, because prior work indicated this modification to be barely detectable at Trdv5 even on wild-type alleles (33). We conclude that defective Trdv5 rearrangement is not the result of altered Trdv5 chromatin accessibility in CBE KI DN thymocytes, even though the CBE KI was situated between Eδ and Trdv5. Nevertheless, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that aspects of chromatin structure not assayed in our experiments might distinguish Trdv5 on wild-type and CBE KI alleles.

Figure 4. The CBE KI does not perturb chromatin accessibility.

(A) Germline transcription of gene segments in WT and CBE KI thymocytes (all on a Rag2−/− background), analyzed by SYBR-Green qPCR. Data were normalized to Hprt and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 WT and 3 CBE KI chromatin preparations, each representing a pool of 2–3 mice. (B) Enrichment of H3Ac in WT and CBE KI DN thymocytes (all on a Rag2−/− background), analyzed by SYBR-Green qPCR. Values of bound/input were normalized to values for B2m. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 WT and 3 CBE KI chromatin preparations, each representing a pool of 5–8 mice. Statistical significance was evaluated by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test.

CBE KI mice have an altered chromatin loop organization

Another explanation for reduced Trdv5 rearrangement is that the CBE KI interferes with the interaction between Trdv5 and Dδ and Jδ gene segment RSSs within the Tcrd RC (6). Therefore, we used 3C–qPCR to examine whether the CBE KI alters the long-distance chromatin loop organization of the Tcra-Tcrd locus. In previous experiments, we showed that INT1and INT2, two intergenic CBEs, are critical nodes in long-distance chromatin loop organization of the 3’portion of the Tcra-Tcrd locus in DN thymocytes, with INT2 forming a high-frequency and presumably stable interaction with the CBE associated with TEA (25). This loop segregates the region spanning from Trdv4 to Trdv5, and including Eδ, from other portions of the Tcra/Tcrd locus. 3C libraries were prepared by HindIII digestion and HindIII fragments were assayed for interactions with the Eδ, D2J1 (Trdd2-Trdj1) and TEA viewpoints (Fig. 5A, 5B). Note that the CBE KI is included in the Eδ HindIII fragment on the CBE KI but not on the wild-type allele. We found that the CBE KI caused a dramatic increase in interactions between Eδ and INT2, whereas interactions between Eδ and other analyzed sites in the locus were unaffected (Fig. 5B, left panel). Notably, increased interactions between Eδ and INT2 were not accompanied by reduced interactions between INT2 and TEA (Fig. 5B, right panel). As a consequence of the strong Eδ-INT2 interaction on CBE KI alleles, Dδ and Jδ gene segments would be confined within a 65 kb loop that newly excludes Trdv5 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, we hypothesized that this new loop organization diminishes contacts between Trdv5 and the Tcrd RC. To test this, we used fragment D2J1 (containing Trdd2 and Trdj1) as a viewpoint (Fig. 5B, right panel). As expected, the D2J1 viewpoint had comparable interactions with Trdv1 on wild-type and CBE KI alleles. However, interactions between the D2J1 viewpoint and Trdv5 were substantially less frequent on CBE KI as compared to wild-type alleles (Fig. 5B, right panel). Therefore, the CBE KI redefines chromatin loops at the Tcra-Tcrd locus in a manner that diminishes contact between Trdv5 and the Tcrd RC, providing a plausible explanation for its effect on Trdv5 rearrangement.

Figure 5. The CBE KI changes the chromatin loop organization.

(A) Map of fragments analyzed by 3C. Gray ovals on the map identify CBEs and gray V segments denote pseudogenes; below the map, viewpoint HindIII fragments (gray rectangles) and target HindIII fragments (numbered black rectangles) are indicated. (B) 3C of WT and CBE KI DN thymocytes (all on a Rag2−/− background) from the Eδ viewpoint (left panel) and from the D2J1 and TEA viewpoints (right panel), analyzed by Taqman qPCR. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three WT and four CBE KI preparations, with normalization to either an Eδ nearest neighbor fragment (left) or a TEA nearest neighbor fragment (right). Statistical significance was evaluated by 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. 3C preparations represent pools of 8–10 mice. (C) Summary of 3C data in WT and CBE KI DN thymocytes. Gray ovals denote CBEs, with orientations indicated by white arrowheads. Interactions between CBEs are indicated by thick gray arcs and interactions between rearranging gene segments are indicated by thin gray arcs that are either solid (for more frequent interactions) or dashed (for less frequent interactions).

CBE KI mice display altered RAG tracking

Recent work suggests that RAG bound to an RSS pair can release one RSS and track uni-directionally along chromatin to capture similarly oriented bona-fide or cryptic RSSs, which can then engage in recombination events (27). Genome-wide analyses suggested that this tracking activity is confined within CTCF-mediated loop domains. This concept was formally tested by analysis of directional RAG activity on two alleles from which CBEs were eliminated by gene targeting. Deletion of IGCR1, a 4.1 kb region of the Igh locus containing two CBEs, allowed RAG to track upstream from the Igh RC to proximal VH gene segments (27). Similarly, deletion of INT1–2, a 5.8 kb region of the Tcra-Tcrd locus containing two CBEs, allowed RAG to track upstream from the Tcrd RC to proximal Vδ gene segments (28). Because the CBE KI was composed of only a single CBE introduced with only limited flanking sequence, and because 3C revealed it to confine the Tcrd RC into a smaller loop than on wild-type alleles, the CBE KI allele offered the most stringent test yet of the role of CBEs in limiting RAG tracking.

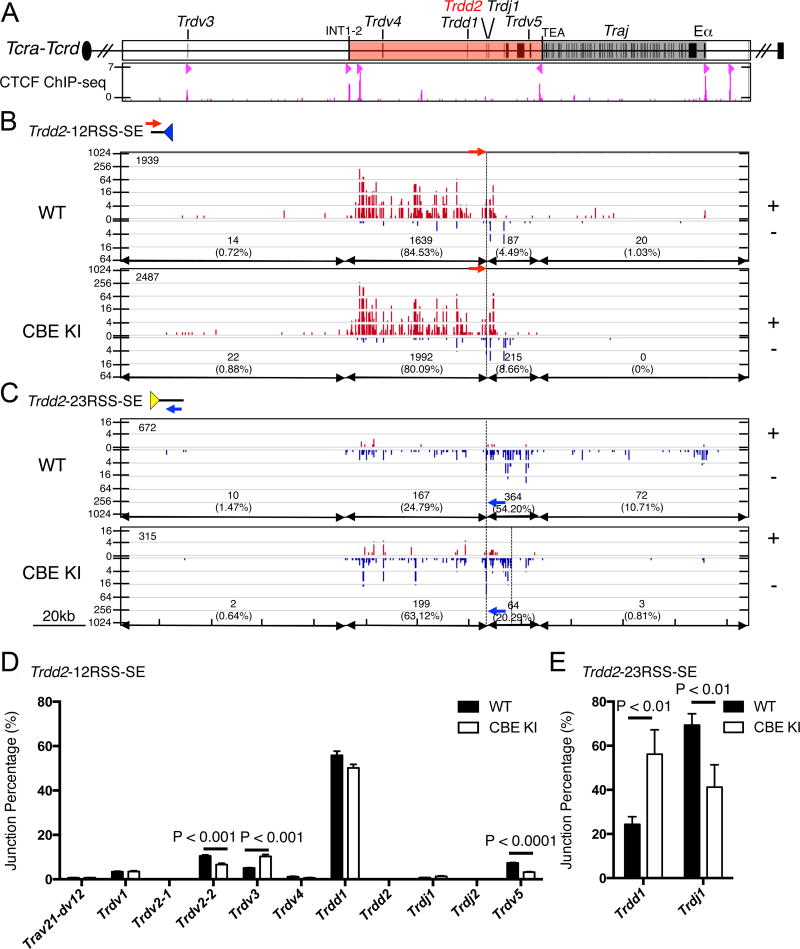

To investigate the potential influence of the CBE KI on directional tracking by RAG, we performed LAM-HTGTS from primary DN2/DN3 T-cell precursors obtained from OP9-DL1 cultures of wild-type and CBE KI bone marrow cells (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Tables 2, 3 and 4). We used a bait primer 75bp upstream of Trdd2 (red arrow) to capture joins involving Trdd2 12RSS signal ends (Trdd2-12RSS-SE) (Fig. 6A, 6B) and a bait primer 64 bp downstream of Trdd2 (blue arrow) to capture joins of Trdd2 23RSS signal ends (Trdd2-23RSS-SE) (Figs. 6C). We assessed joining to cryptic RSSs, which contain, minimally, the highly conserved first three bases, CAC, of the RSS heptamer sequence (Fig. 6B, 6C). These are referred to as off-target joins. We separately assessed joining to bona-fide RSSs, which contain intact and appropriately spaced heptamer and nonamer sequences (Fig. 6D, 6E). These are referred to as on-target joins.

Figure 6. The CBE KI blocks RAG tracking from the Trdd2 23RSS towards TEA.

(A) Top: Gene segment organization of the 3’ portion of the Tcra-Tcrd locus. The INT1-2 to TEA CTCF-dependent loop domain is shaded red and the Traj cluster is shaded gray. Bottom: CTCF ChIP-seq profile, with CBE orientations indicated by red triangles. (B–C) IGV plots of RAG off-target joining patterns in wild-type and CBE KI using (B) the Trdd2-12RSS-SE as bait (n=3) and (C) the Trdd2-23RSS-SE as bait (n=3). The bait primers are indicated by red and blue arrows in (B) and (C), respectively. The dashed line shared by all plots denoted Trdd2. The additional dashed line in the bottom panel of (C) marks the CBE KI. The total number of off-target junctions is indicated in the upper left corner of each panel and the number and percentage of those junctions mapping to specified regions are indicated on the bottom of each panel. Trdd2-12RSS-SE WT and Trdd2-12RSS-SE CBE KI are normalized to 103,163 junctions. Trdd2-23RSS-SE WT and Trdd2-23RSS-SE CBE KI are normalized to 59,791 junctions. (D,E) Bar graphs quantify on-target joining patterns in wild-type and CBE KI as average junction percentages from (D) Trdd2-12RSS-SE bait libraries (n=3) and (E) Trdd2-23RSS-SE bait libraries (n=3). Data represent the mean ± SD, with statistical significance determined by unpaired Student’s t-test.

Due to the relative abundance of off-target CAC sequences, a plot of joining frequencies to these sites creates a relatively continuous map of RAG activity which, because it is strongly biased to a particular CAC orientation, is most easily interpreted in terms of directional RAG tracking along chromatin (27, 28). In wild-type and CBE KI thymocytes,Trdd2-12RSS-SEs joined almost exclusively to upstream RAG off-target sequences with convergent CAC motifs (“+ orientation”, meaning they read 5’-CAC-3’ from centromere to telomere [on the top strand], with the 12RSS heptamers and CAC sequences joined on excision circles) (Fig. 6B). In both cases, these off-target joins extended to the INT1–2 CBEs, but no farther (Fig. 6B). In contrast, Trdd2-23RSS-SEs were joined primarily to downstream RAG off-target sites with convergent CAC motifs (“− orientation”, meaning they read 5’-CAC-3’ from telomere to centromere [on the bottom strand], with the 23RSS heptamers and CAC sequences joined on excision circles) (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the results of prior analysis (28), these off-target joins appeared to be limited primarily by the TEA CBE on wild-type alleles, although some extended as far as Eα. However, these joins ended abruptly at the newly introduced CBE on CBE KI alleles (Fig. 6C, note right-most dashed line in the bottom panel). Our interpretation is that the introduced CBE can create a functional boundary for RAG off-target activity by limiting directional RAG tracking from the Tcrd RC to the boundaries of the newly formed INT2-CBE KI loop.

Trdd2-12RSS-SE joins to bona-fide RSS targets were captured as excision circle joins to upstream (+ orientation) 23RSSs or as inversional chromosomal joins to downstream (− orientation) 23RSSs. Consistent with the results of coding joint PCR assays (Fig. 2B), we observed a substantial 56% reduction in inversional joining to Trdv5 on CBE KI alleles (Fig. 6D, Supplemental Table 4). Since the Trdd2-12RSS cannot capture downstream (−) orientation CACs or RSSs by a directional RAG tracking mechanism (Fig. 6B), inversional Trvd5-to-Trdd2 rearrangement must occur as the result of chromatin interactions dependent on looping which brings together the Trdv5-23RSS and the Trdd2-12RSS. Consequently, differential RAG tracking cannot be invoked to explain reduced Trdv5 rearrangement on CBE KI alleles.

Unexpectedly, analysis of Trdd2-12RSS-SE joins also revealed a modest reduction in deletional joining to Trdv2-2 (37%)(Fig. 6D, Supplemental Table 4), which was not apparent in PCR analysis (Fig. 2B), and a 2-fold increase in joining to Trdv3, a pseudogene 3’ of Trdv2-2 (Fig. 6D, Supplemental Table 4). Divergent results for Trdv2-2 in coding joint PCRs and LAM-HTGTS could reflect distinctions between the cell populations analyzed in the two assays, since the former were DN3 thymocytes analyzed immediately ex vivo and the latter were DN2/3 thymocytes generated by in vitro culture.

Finally, analysis of Trdd2-23RSS-SE joints revealed a 38% decrease in Trdd2-Trdj1 joining and a 2.3-fold increase in Trdd2-Trdd1 joins which eliminate the two D segments, leaving a Trdd1-12RSS-Trdd2-23RSS signal joint on the chromosome (Fig. 6E, Supplemental Table 4). The basis for and significance of these differences is uncertain, particularly since LM-qPCR revealed no significant differences in RAG-mediated cleavage at the 12RSSs flanking either Trdd1 or Trdj1 in wild-type and CBE KI DN3 thymocytes in vivo (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

Here, we show that an ectopic CBE inserted between Trdv5 and the Tcrd RC impaired RAG-mediated DNA-cleavage at the Trdv5 RSS, resulting in defective rearrangement of Trdv5. We found that the CBE KI had no apparent effect on Trdv5 accessibility. Rather, it created a new chromatin loop that segregated Trdv5 from the RC, limited directional RAG tracking from the RC, and limited RAG-independent interactions between Trdv5 and the RC. Because directional RAG tracking from the RC cannot account for inversional rearrangement of Trdv5, we conclude that defective Trdv5 rearrangement is a specific consequence of reduced contact between Dδ and Trdv5 RSSs. As such, our data provide strong evidence that CTCF-dependent chromatin loops can segregate RSSs to regulate the frequency of RSS synapsis and V(D)J recombination by a contact mechanism, independent of effects of such looping on transcriptional insulation (and thus accessibility) or on RAG tracking. This conclusion is significant, because in all prior instances in which CTCF-mediated looping was shown to influence V(D)J recombination, the relative contributions of changes in accessibility, RAG-tracking, and RAG-independent long-distance interactions were not fully resolved (19–28).

Our data are also of interest because we show that introduction of a single CBE with limited flanking sequence can impede the directional spreading of RAG activity from the Tcrd RC. This is significant, because prior studies demonstrating a causal relationship between CBE organization and RAG tracking relied on deletion of CBE-containing genomic segments of 4–6 kb (19, 25, 27, 28). Moreover, the genomic segments deleted contained two CBEs. Thus it could not be concluded with certainty whether the CBEs were the critical delimiters of RAG tracking, whether they did so alone or by synergizing with other elements in those genomic regions, or whether a single CBE would be similarly effective. Therefore, our results strengthen the argument that CTCF binding (and presumably CTCF-mediated looping) is a critical determinant of the distribution of RAG proteins along chromatin.

Although the introduced CBE provoked a substantial increase in looping between Eδ and INT2, we did not detect an increase in looping from Eδ to TEA. This was surprising, because recent studies have identified a strong bias for interactions between convergently oriented CBEs (40, 41); the CBE KI (>) is convergent with the TEA CBE (<) but is in the same orientation as the INT2 CBE (>), with which it appears to preferentially interact. In this regard, we note that in its endogenous location, the Eα-proximal CBE (> orientation) is convergent with no other CBEs in the Tcra-Tcrd locus, but interacts with many of those CBEs (25, 26).

Increased looping between Eδ and INT2 also did not occur at the expense of looping between INT2 and TEA. This lack of competition could suggest that INT2 normally interacts with TEA on only a subset of alleles, and that the newly introduced CBE interacts on a distinct subset. However, we note that the INT2- and TEA-mediated blockades to RAG tracking on wild-type alleles, and the INT2- and CBE KI-mediated blockades to RAG tracking on CBE KI alleles, are nearly complete. Unless RAG tracking is curtailed simply by bound CTCF, rather than CTCF-mediated looping, these results would argue that the INT2-TEA and INT2-CBE KI loops are both likely to be present on the majority of alleles in CBE KI mice, and that all three elements may be in proximity simultaneously.

We previously showed that Trdv5 transcription was regulated by Eδ, since it was significantly reduced on Eδ-deleted alleles (33). Since Trdv5 transcription was unaltered on CBE KI alleles, it appears that the introduced CBE does not function as an insulator. One potential difference between this and other examples in which CBEs appeared to function as insulators is that the CBE KI is composed of a single CBE. In contrast, IGCR1 in the Igh locus, Sis and Cer in the Igk locus, and the H19-ICR all contain multiple CBEs. These regions could also contain sequences that recruit other proteins which cooperate with CTCF to mediate insulation, including those mediating covalent modification of CTCF (14).

Finally, our results shed additional light on the distinctions between Eδ-dependent and Eα-dependent regulation of the Tcra-Tcrd locus. Prior studies demonstrated that Eδ has a range that is much more restricted than Eα; in particular, Eδ can influence transcription and accessibility of only the two most proximal V gene segments, Trdv4 and Trdv5, whereas Eα regulates many V gene segments distributed across the proximal 1/3 of the V gene array (33, 35). This distinction could contribute to the much more limited breadth of Vδ repertoire as compared to the Vα repertoire (38). This difference in range was previously attributed to an intrinsic feature of Eδ, because when Eδ was repositioned so that it replaced Eα, it could no longer activate its natural targets, Trdd2 and Trdj1, now 100 kb distant (37). However, this substitution eliminated not only Eα, but also the Eα-proximal CBE, raising the possibility that the absence of a flanking CBE, either in its natural or ectopic location, was causal in relegating Eδ to a limited sphere of influence. In the present study, by supplying Eδ with the Eα CBE, we detected no substantial changes in the repertoire of V gene segments used in Tcrd rearrangements, and no changes in V gene segment transcription and histone modifications, other than the changes documented for Trdv5. Therefore, our results support the contention that the limitations of Eδ are an intrinsic property of the enhancer. In this regard, although we previously found that INT1–2 deletion allowed the Eδ region to make more frequent contacts with upstream V gene segments, we detected no changes in V segment transcription or chromatin modification (25).

In summary, our results emphasize the importance of CTCF-mediated looping as a modulator of AgR repertoires. We showed that by redirecting chromatin looping, a single CBE can constrain directional RAG tracking and can independently limit long-distance contacts between RSSs in a RAG-independent fashion. Because only the latter can explain reduced Trdv5 rearrangement in CBE KI mice, we conclude that limiting RSS contacts by segregation into distinct loops represents an important mechanism by which chromatin looping may influence V(D)J recombination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Bock of the Duke Cancer Institute Transgenic and Knockout Mouse Shared Resource for the production of mice with gene targeting, L. Martinek, N. Martin and M. Cook of the Duke Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Shared Resource for help with cell sorting and analysis, Z. Huang and A. Byrd for technical support, and D. Dauphars and Z. Carico for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R37 GM41052 (to M.S.K.) and RO1 AI020047 (to F.W.A). F.W.A. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Abbreviations used in this paper: 3C, chromosome conformation capture; AgR, antigen receptor; CBE, CTCF binding element; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CTCF, CCCTC binding factor; DSB, double-stranded break; DN, double-negative; DP, double-positive; Eα, Tcra enhancer; Eδ, Tcrd enhancer; ES, embryonal stem; H3Ac, histone H3 acetylation; ICR, imprinting control region; IGCR1, intergenic control region 1; KI, knock-in; LAM-HTGTS, linear amplification mediated high throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing; RC, recombination center; RSS, recombination signal sequence; TEA, T early alpha.

References

- 1.Schatz DG, Ji Y. Recombination centres and the orchestration of V(D)J recombination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:251–263. doi: 10.1038/nri2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatz DG, Swanson PC. V(D)J recombination: mechanisms of initiation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiom K, Gellert M. Assembly of a 12/23 paired signal complex: a critical control point in V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji Y, Little AJ, Banerjee JK, Hao B, Oltz EM, Krangel MS, Schatz DG. Promoters, enhancers, and transcription target RAG1 binding during V(D)J recombination. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2809–2816. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji Y, Resch W, Corbett E, Yamane A, Casellas R, Schatz DG. The in vivo pattern of binding of RAG1 and RAG2 to antigen receptor loci. Cell. 2010;141:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng G, Maman Y, Resch W, Kim M, Yamane A, Qian J, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Mandal M, Ji Y, Meffre E, Clark MR, Cowell LG, Casellas R, Schatz DG. RAG Represents a Widespread Threat to the Lymphocyte Genome. Cell. 2015;162:751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuxa M, Skok J, Souabni A, Salvagiotto G, Roldan E, Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. 2004;18:411–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roldan E, Fuxa M, Chong W, Martinez D, Novatchkova M, Busslinger M, Skok JA. Locus ‘decontraction’ and centromeric recruitment contribute to allelic exclusion of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:31–41. doi: 10.1038/ni1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skok JA, Gisler R, Novatchkova M, Farmer D, de Laat W, Busslinger M. Reversible contraction by looping of the Tcra and Tcrb loci in rearranging thymocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:378–387. doi: 10.1038/ni1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih HY, Krangel MS. Distinct contracted conformations of the Tcra/Tcrd locus during Tcra and Tcrd recombination. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1835–1841. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhunjhunwala S, van Zelm MC, Peak MM, Cutchin S, Riblet R, van Dongen JJ, Grosveld FG, Knoch TA, Murre C. The 3D structure of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus: implications for long-range genomic interactions. Cell. 2008;133:265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jhunjhunwala S, van Zelm MC, Peak MM, Murre C. Chromatin architecture and the generation of antigen receptor diversity. Cell. 2009;138:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih HY, Krangel MS. Chromatin architecture, CCCTC-binding factor, and V(D)J recombination: managing long-distance relationships at antigen receptor loci. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4915–4921. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong CT, Corces VG. CTCF: an architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:234–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, Loh YH, Yeo HC, Yeo ZX, Narang V, Govindarajan KR, Leong B, Shahab A, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Sung WK, Clarke ND, Wei CL, Ng HH. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, Zhang MQ, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuddapah S, Jothi R, Schones DE, Roh TY, Cui K, Zhao K. Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res. 2009;19:24–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.082800.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee HS, Pugh BF. Comprehensive genome-wide protein-DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell. 2011;147:1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo C, Yoon HS, Franklin A, Jain S, Ebert A, Cheng HL, Hansen E, Despo O, Bossen C, Vettermann C, Bates JG, Richards N, Myers D, Patel H, Gallagher M, Schlissel MS, Murre C, Busslinger M, Giallourakis CC, Alt FW. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro de Almeida C, Stadhouders R, de Bruijn MJ, Bergen IM, Thongjuea S, Lenhard B, van Ijcken W, Grosveld F, Galjart N, Soler E, Hendriks RW. The DNA-binding protein CTCF limits proximal Vκ recombination and restricts κ enhancer interactions to the immunoglobulin κ light chain locus. Immunity. 2011;35:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang Y, Park SK, Garrard WT. Vκ gene repertoire and locus contraction are specified by critical DNase I hypersensitive sites within the Vκ-Jκ intervening region. J. Immunol. 2013;190:1819–1826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang Y, Park SK, Garrard WT. A major deletion in the Vκ-Jκ intervening region results in hyperelevated transcription of proximal Vκ genes and a severely restricted repertoire. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3746–3754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shrimali S, Srivastava S, Varma G, Grinberg A, Pfeifer K, Srivastava M. An ectopic CTCF-dependent transcriptional insulator influences the choice of Vβ gene segments for VDJ recombination at TCRβ locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:7753–7765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma G, Rawat P, Jalan M, Vinayak M, Srivastava M. Influence of a CTCF-dependent insulator on multiple aspects of enhancer-mediated chromatin organization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015;35:3504–3516. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00514-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Carico Z, Shih HY, Krangel MS. A discrete chromatin loop in the mouse Tcra-Tcrd locus shapes the TCRδ and TCRα repertoires. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:1085–1093. doi: 10.1038/ni.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shih HY, Verma-Gaur J, Torkamani A, Feeney AJ, Galjart N, Krangel MS. Tcra gene recombination is supported by a Tcra enhancer- and CTCF-dependent chromatin hub. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E3493–E3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214131109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu J, Zhang Y, Zhao L, Frock RL, Du Z, Meyers RM, Meng FL, Schatz DG, Alt FW. Chromosomal loop domains direct the recombination of antigen receptor genes. Cell. 2015;163:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao L, Frock R, Du Z, Hu J, Chen L, Krangel MS, Alt FW. Orientation-specific RAG activity in chromosomal loop domains contributes to Tcrd V(D)J recombination during T cell development. J.Exp.Med. 2016 doi: 10.1084/jem.20160670. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlissel M, Constantinescu A, Morrow T, Baxter M, Peng A. Double-strand signal sequence breaks in V(D)J recombination are blunt, 5’-phosphorylated, RAG-dependent, and cell cycle regulated. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2520–2532. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMurry MT, Hernandez-Munain C, Lauzurica P, Krangel MS. Enhancer control of local accessibility to V(D)J recombinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4553–4561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes R, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. The OP9-DL1 system: generation of T-lymphocytes from embryonic or hematopoietic stem cells in vitro. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J, Garrett KP, Pelayo R, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Petrie HT, Kincade PW. Propensity of adult lymphoid progenitors to progress to DN2/3 stage thymocytes with Notch receptor ligation. J. Immunol. 2005;175:4858–4865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao B, Krangel MS. Long-distance regulation of fetal Vδ gene segment TRDV4 by the Tcrd enhancer. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2484–2491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monroe RJ, Sleckman BP, Monroe BC, Khor B, Claypool S, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt FW. Developmental regulation of TCRδ locus accessibility and expression by the TCRδ enhancer. Immunity. 1999;10:503–513. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawwari A, Krangel MS. Regulation of TCR δ and α repertoires by local and long-distance control of variable gene segment chromatin structure. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:467–472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleckman BP, Bardon CG, Ferrini R, Davidson L, Alt FW. Function of the TCRα enhancer in αβ and γδ T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:505–515. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bassing CH, Tillman RE, Woodman BB, Canty D, Monroe RJ, Sleckman BP, Alt FW. T cell receptor (TCR) α/δ locus enhancer identity and position are critical for the assembly of TCR δ and α variable region genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:2598–2603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437943100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carico Z, Krangel MS. Chromatin dynamics and the development of the TCRα and TCRδ repertoires. Adv. Immunol. 2015;128:307–361. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abarrategui I, Krangel MS. Germline transcription: a key regulator of accessibility and recombination. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009;650:93–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0296-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudan MV, Barrington C, Henderson S, Ernst C, Odom DT, Tanay A, Hadjur S. Comparative Hi-C reveals that CTCF underlies evolution of chromosomal domain architecture. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1297–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Wit E, Vos ES, Holwerda SJ, Valdes-Quezada C, Verstegen MJ, Teunissen H, Splinter E, Wijchers PJ, Krijger PH, de Laat W. CTCF binding polarity determines chromatin looping. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:676–684. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.