Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests the protective role of dietary lycopene against the risk of ovarian cancer due to its antioxidant activity, but not all relevant studies have deduced positive results. The aim of the present study was to investigate the exact relationship between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk by conducting a meta-analysis. The 10 studies included in our meta-analysis were selected from the PubMed database, and final risk estimates were calculated by using a random-effects model. Our study demonstrated an insignificant reverse association between dietary lycopene and ovarian cancer risk (OR, 0.963; 95% CI, 0.859–1.080), and subgroup analysis stratified by study design, location, histological type of ovarian cancer, and length of dietary recall showed no statistically significant results. No heterogeneity was observed (p = 0.336, I2 = 11.6%). Our present meta-analysis suggests the potential role of dietary lycopene against the risk of ovarian cancer among postmenopausal women, which provides opportunity for developments in the prevention of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common gynaecological malignancies among women, especially women aged ≥50 years1. It is also associated with the highest mortality and poorest survival because it is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage; the 5-year survival rate is often below 25% to 30%2. Therefore, approaches that could prevent the development of ovarian cancer or decrease the risk of this disease are important and urgent.

The aetiology of ovarian cancer might be multifactorial. In addition to genetic, familial, and reproductive factors, population-based studies have showed that patients with ovarian cancer have significantly higher levels of oxidative stress and lower levels of plasma antioxidants, which suggests that oxidative stress might play an important role in ovarian carcinogenesis3,4,5,6. Oxidative stress could increase DNA damage during successive ovulations and result in the malignant transformations of ovarian cells3. Thus, limiting oxidative stress might be an effective defence against ovarian cancer. Furthermore, the differences in the morbidity of ovarian cancer and dietary patterns among various countries suggest that dietary and lifestyle factors might have a close relationship with the risk of ovarian cancer7. Accordingly, high consumption of dietary antioxidants, such as carotenoids, might help to prevent ovarian cancer and reduce the cancer risk8,9.

Lycopene, which is mainly obtained from vegetables and fruits, is the most efficient carotenoid due to its activity as a singlet oxygen quencher and peroxyl radical scavenger. Recent studies have evaluated the relationship between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk, but epidemiological studies have obtained inconsistent results. The majority of previous studies have yielded a reverse association between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk10,11,12,13,14,15, while others have failed to provide evidence supporting the protective role of lycopene, including the U.S. Nurses Health Study16, an Italian cohort study17, and other studies on dietary fruit and vegetable intake and ovarian cancer risk18,19,20.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to address this suspected association between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk among elderly women by conducting a meta-analysis.

Results

Paper selection

We initially obtained 134 papers from the PubMed database, most of which were excluded after reviewing the title and abstracts (i.e., they were reviews, not population-based research, or had research exposure irrelevant to our analysis). After reviewing the full texts of 34 potentially relevant articles, 20 basic experimental studies were excluded. Of the remaining 14 papers, two studies were related to circulating lycopene21,22 and two were duplicate publications23,24. Thus, 10 studies were included in our meta-analysis10,11,12,13,14,15,17,25,26,27.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the selected studies are shown in Table 1. Of the 10 studies, three were prospective and seven were case-control studies. These seven studies included four hospital-based and three population-based case-control studies. All studies were published from 2001 to 2013. Two were conducted in China10,27, one in the European region17, and the remaining seven in the US11,12,13,14,15,25,26. Eight studies only included postmenopausal women, and two included both pre- and postmenopausal women13,14. The majority of all participants were older than 50 years and nonsmokers. The response rate varied from 47.0% to 99.6%. Food consumption was assessed by a food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ), and the lycopene content was calculated using the US Department of Agriculture-National Cancer Institute Carotenoid Database with the exception of one study17, which used the Italian food composition database. Our meta-analysis did not include supplementation of lycopene. The length of dietary recall prior to the date of entry into each study for controls and the diagnosis date for cases varied widely from 3 months to 5 years. Case ascertainment was mainly performed using medical records and pathology reports or by the national cancer registry. In the three prospective studies, the duration of follow-up ranged from 8.3 to 16.0 years (median, 12 years). The number of cases ranged from 71 to 2012, and 2543 cases of ovarian cancer occurred among 668,806 participants. The case-control studies included 3584 cases and 6502 controls. The main confounding factors adjusted for were age, education, race, age at menarche, menopausal status, age at menopause for postmenopausal women, parity, oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy use, body mass index, tubal ligation, total calories, physical activity, and smoking status. These data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies in our meta-analysis.

| Study(Ref) | Study design | No. Case/control OR Case/participants | Case age | Case ascertainment | Menopausal status | Response rate | Assessment of lycopene | Length of dietary recall* | Lycopene dose | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang, 2013, Guangzhou (10) | HBCC | 500/500 | <75 y | Medical records, pathology reports | postmenopausal | 98% | face-to-face interview using a validated and reliable FFQ, content was identified and estimated using the nutrient database of the USDA | over the past five years | <405 ~ >811 ug | age at interview,education level, BMI, physical activity, fresh meat consumption, seafood consumption, total energy intake, parity, OC use, menopausal status, tubal ligation, HRT, smoking status, alcohol drinking, and family history of ovarian or breast cancer in first-degree relatives. |

| Gifkins, 2012, New Jersey (29) | PBCC | 205/391 | >21 y | using rapid case ascertainment, supplemented with review of NJSCR data | postmenopausal | case:47%; control:40% | Using the Block FFQ and the USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference to calculate individual antioxidants. | over the past six months | <2504 ~ >5465 mcg | age, education, race, age at menarche, menopausal status and age at menopause for postmenopausal women, parity, OC use, HRT use, BMI, tubal ligation, and total calories; physical activity,smoking status |

| Thomson, 2008, United States (30) | PS | 451/133614 | 63.2 ± 7.3 y | self-report combined with relevant medical records, including pathology reports | postmenopausal | 83% | By WHI semi quantitative FFQ | over the past 3 months | <2736 ~ >6325 mcg | age, log calories, No. breast/ovary cancer relatives, dietary modificationrandomization arm, hysterectomy status, minority race, pack-years smoking, physical activity, non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, parity, infertility, duration of OC use, lifetime ovulatory cycles, partial oophorectomy, age at menopause, and HRT usage at entry |

| Zhang, 2007, Hangzhou (31) | HBCC | 254/652 | 46.8 y | from medical records | 60% was postmenopausal | 99.6% | by face-to-face interview using a validated and reliable FFQ. Nutrients intake were calculated based on daily food consumption using a USDA nutrient database | 5 years before | <2509 ~ >11 857 ug | terms for age at interview, locality and education, BMI, tobacco smoking, tea drinking, parity, OC use, HRT, menopausal status, physical activity, family history of ovarian cancer and total energy intake. |

| Koushik, 2006, North America and Europe (11) | PS | 2012/521911 | Not available | using follow-up questionnaires with subsequent medical record review, linkage with a cancer registry or both or Mortality registries | Not available | >92% | Using a self-administered FFQ. Daily consumption of each of the carotenoids was calculated by the original study investigators using food composition databases. | Not available | Not available | parity, OC use, menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use, age at menarche, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, total energy intake, age in years and year of questionnaire return |

| Kiani, 2006, United States (12) | PS | 71/13281 | >25 y | Not available | postmenopausal | Not available | Not available | Not available | Never to <1/w vs >5/w | age, parity, BMI, age at Menopause, HRT,stipulated dietary variables |

| Tung, 2005, Hawaii and Los Angeles (13) | PBCC | 558/607 | 54.8 y | histologically confirmed | mix | case:62%; control:67% | By the FFQ and The 1993 USDA. Carotenoid Database to estimate specific dietary carotenoid contents | 1 year | 4659 ug ~ 1542 ug | age, ethnicity, study site, education, OC pill use, pregnancy status, tubal ligation, and energy intake |

| La,2002, Italy (17) | HBCC | 1031/2411 | 56 y | histologically confirmed | 2/3 of cases and controls were in post-menopause | >95% | using a validated FFQ and Italian food-composition databases | two years l | highest vs lowest quintile | age, study center, year of interview, education, BMI, parity, OC use, occupational physical activity, energy intake |

| Cramer, 2001, Massachusetts or New Hampshire (14) | PBCC | 549/516 | Not available | hospital tumor boards and statewide cancer registries. | mix | Not available | A previously validated self-administered FFQ and the USDA-NCI carotenoid database | 1 year | >15262 ~ <4743 ug/d | total caloric intake, age, site, parity, BMI, OC use, family history of breast, ovarian or prostate cancer in a first-degree relative, tubal ligation, education, marital status |

| McCann, 2001, Western New York (15) | HBCC | 496/1425 | 55.1 y | identified from the RPCI tumor registry and diagnostic index | postmenopausal | 50% | Using FFQ and regression weights to calculate nutrient intake | few years | >6684 ~ <2362 ug/d | age, education, region of residence, regularity of menstruation, family history of ovarian cancer, parity, age at menarche, OC use, total energy intake. |

*: time before diagnosis for cases and before interview for controls.

HBCC: hospital-based case–control; PBCC: population-based case-control; PS: Prospective study; NJSCR: New Jersey State Cancer Registry; FFQ: food frequency questionnaire; USDA: United States Department of Agriculture; BMI: body mass index; OC: oral contraceptive; HRT: hormone replacement therapy.

Dietary lycopene and ovarian cancer risk

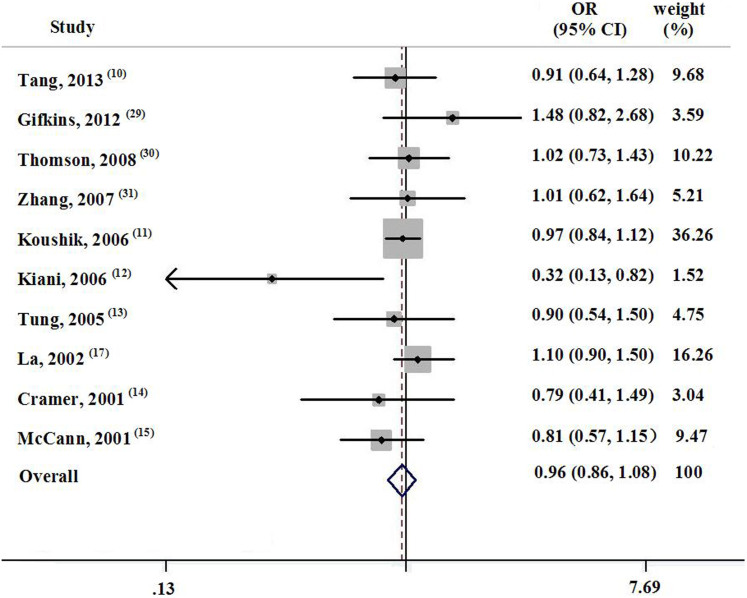

The adjusted ORs of the individual studies with corresponding 95% CIs and the pooled ORs are displayed in Figure 1. Of the 10 selected studies, six showed a negative association between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk, with one showing statistical significance. Dietary lycopene consumption decreased the risk of ovarian cancer by 3.7% (OR, 0.963; 95% CI, 0.859–1.080), and no heterogeneity was observed across the studies (p = 0.336, I2 = 11.6%).

Figure 1. Forest plot about the association between dietary lycopene and ovarian cancer.

The study design had no effect on the relationship between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk. The pooled OR for case-control studies and prospective studies was 0.981 (95% CI, 0.846–1.139; n = 7) and 0.871 (95% CI, 0.616–1.233; n = 3), respectively. The final risk estimate for studies conducted in and outside of the US was 0.923 (95% CI, 0.770–1.106; n = 7) and 1.026 (95% CI, 0.849–1.240; n = 3), respectively. Histologically, the OR for serous ovarian cancer and mucinous ovarian cancer was 0.744 (95% CI, 0.545–1.016; n = 4) and 0.878 (95% CI, 0.554–1.393; n = 3), respectively. Limiting the analysis to studies with higher response rates (>90%) resulted in an OR of 0.967 (95% CI, 0.849–1.102; n = 7). Similarly, when stratifying the results by the length of dietary recall before entering the research, omitting the studies with a recall duration of <1 year resulted in an OR of 0.973 (95% CI, 0.823–1.149; n = 3). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in the subgroup analysis.

We conducted sensitivity analysis by omitting one study from each analysis to investigate the effect of a single study on the pooled results. No study had a substantial effect on the final risk estimate; the pooled OR varied from 0.938 to 0.981.

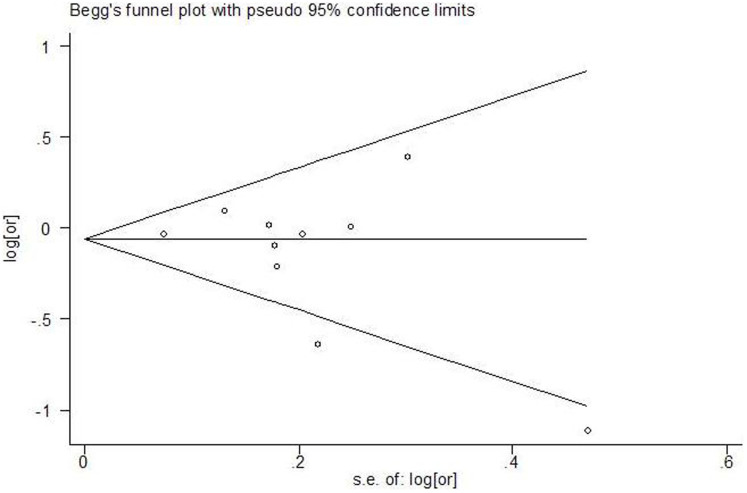

Results of publication bias

Funnel plots (as displayed in Figure 2) with Begg's and Egger's tests did not support the existence of publication bias (Begg, p = 0.251; Egger, p = 0.406).

Figure 2. Funnel plot about dietary lycopene and ovarian cancer.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of seven case-control studies and three prospective studies that included 678,892 subjects and 6127 cases demonstrated an insignificant inverse association between dietary lycopene consumption and ovarian cancer risk. Dietary lycopene intake resulted in a 3.7% (OR, 0.963; 95% CI, 0.859–1.08) lower risk of ovarian cancer, as compared to lycopene intake after adjusting for potential confounding factors. This is consistent with previous studies of the beneficial effect of dietary lycopene on ovarian cancer risk10,11,12,13,14,15. Further subgroup analysis showed that the research location, study design, response rate of participants to the study, and histological type of ovarian cancer did not affect the relationship between dietary lycopene consumption and the risk of ovarian cancer. We observed no heterogeneity across the studies.

Our insignificant results might be explained as follows. First, the majority of participants in our study were older than 50 years. Cramer et al. reported that the protective role of dietary lycopene against ovarian cancer was much stronger in premenopausal women (<50 years) than in postmenopausal women (>50 years)14. Fairfield's study on the association between fruit and vegetable consumption and ovarian cancer risk deduced similar results16. Accordingly, the effect of lycopene on ovarian cancer risk might be stronger in early life than in later life. Because the postmenopausal period is associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer, and because most studies included postmenopausal women (2 of 10 studies presented their results as stratified by menopausal status13,14), we cannot definitively determine the effect of lycopene on premenopausal patients. Second, the protective role of lycopene against ovarian cancer might be related to the type of ovarian cancer. Chiaffarino et al. found that dietary carotenoids could protect against serous ovarian cancer, but not mucinous, endometrial, or other histological types28. Cramer et al. also found that lycopene could significantly protect against serous, especially borderline, ovarian cancer14. Both of these results suggest a latent relationship between the role of lycopene and the histological type of ovarian cancer. Only four and three studies provided the OR of the effect of lycopene on serous and mucinous ovarian cancer, respectively, and the effect of lycopene on serous and mucinous ovarian cancer risk was deemed to be insignificant in all studies. This might be attributed to inadequate statistical power, and it is possible that the histological types in our included studies did not include serous ovarian cancer, but other types. Third, underestimation of lycopene intake might have contributed to the observed null association in the present study. Because there was no available database from the Chinese Food Composition tables with which to calculate the lycopene content, two studies10,27 conducted in China used the USDA nutrients database instead. This might have led to underestimation of the lycopene intake because some fruits and vegetables commonly consumed in China are not covered by the USDA database, such as guava10.

The underlying mechanisms by which dietary lycopene reduces the risk of ovarian cancer might be multifactorial, but are likely to involve its activity as a singlet oxygen quencher and peroxyl radical scavenger. These activities may protect ovarian epithelial cells from oxidative stress and prevent malignant transformation of ovarian cells.

Limitations of the present study should be addressed. First, inherent limitations of case-control studies are recall bias and selection bias. Seven of 10 studies in our analysis were case-control studies, and dietary assessment was based on a self-reported FFQ, which probably introduced some recall error. Among these seven studies, the use of hospital-based controls might have introduced selection bias because of the possibility that some controls might have had characteristics different from those of the general population. Second, misclassification of dietary lycopene intake may have occurred. The lycopene content was calculated based on the dietary information collected at baseline using only the FFQ, which might have been subject to measurement error. Individual differences in food preparation and the concurrent consumption of other foods could have also affected the lycopene bioavailability29,30,31. Dietary intake just prior to the diagnosis of ovarian cancer does not reflect longer-term dietary lycopene intake levels. Third, no analysis of the association between plasma levels of lycopene and ovarian cancer risk was performed. A biomarker approach would have the advantage of reducing measurement error associated with self-reports of dietary intake32,33. Finally, incomplete control for confounding factors may have existed in some studies, such as the levels of physical activity and alcohol drinking.

In summary, our meta-analysis has demonstrated that dietary lycopene intake could potentially decrease the ovarian cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Although the results did not reach statistical significance, they trended toward a beneficial role of lycopene in decreasing the risk of ovarian cancer. Other factors that should be considered in future research include the relationship between lycopene and different subtypes of ovarian cancer, the effect of menopausal status on the role of lycopene in ovarian cancer risk, and the role of lycopene in women of different ages, particularly those aged <50 years. Because individual carotenoids have different antioxidant capacities, total carotenoids might be more effective than any single carotenoid in reducing the cancer risk. Prospective studies with larger numbers of patients from all age groups are required to determine the exact association between dietary lycopene and ovarian cancer risk.

Methods

Literature collection

Studies included in our final meta-analysis were selected after screening the PubMed database and Cochran library through December 2013 using the search terms “lycopene”, “tomato”, “carotenoids”, and “ovarian cancer” with limitation to “humans”. Relevant reviews, the PubMed option “Related Articles”, and references of included studies were also reviewed to find additional potentially relevant studies. Abstracts and papers without full texts were excluded.

Inclusion criteria

Only studies that met the following criteria were included in our meta-analysis: (1) population-based studies, such as case-control or prospective studies; (2) dietary lycopene or tomato was the exposure factor; (3) the odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) between lycopene and ovarian cancer risk were provided, and (4) there was no restriction on the age of the patients.

Data extraction

Data included in the final meta-analysis were extracted in a standardized manner according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration34 and Stroup et al.35 The last name of the first author, publication year, country, study design, characteristics of the subjects, determination of dietary lycopene intake, diagnosis of ovarian cancer, adjusted risk estimate between lycopene and ovarian risk with the corresponding 95% CI, and adjustment for confounding factors were independently extracted by X-L LI and J-H X, and disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Statistical methods

ORs were used to evaluate the association between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk, and RR was directly considered as the OR when the incidence of ovarian cancer was low. For studies that presented graded associations, only the estimate for the highest vs lowest level was selected in the final meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity tests were performed using the Q-test and I2 statistic, with p < 0.10 indicating statistical significance. A random-effects model was used to calculate the final risk estimates when the heterogeneity test was statistically significant; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used36.

Subgroup analysis was conducted to address the effect of various study characteristics on the pooled risk.

To assess the source of heterogeneity and the robustness of the association between dietary lycopene intake and ovarian cancer risk, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using both fixed- and random-effects models, omitting one study for each analysis.

Funnel plots, Begg and Mazumdar's rank correlation test, and Egger's test of the intercept were employed to assess the potential publication bias; and p < 0.10 suggested statistical significance37.

All analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corp). A p value of <0.05 denoted statistical significance unless otherwise specified.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No_81001185, 81372980] and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.H.X. and X.L.L. conducted the literature search, determined studies for exclusion and inclusion, extracted data from retrieved studies, performed the meta-analysis, and drafted the manuscript of the methods. X.L.L. recovered the publications, determined studies for exclusion and inclusion, extracted data from retrieved studies and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the paper and approved the final manuscript.

07/11/2014

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

- Ferlay J. et al. GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. IARC Cancer Base No. 10.: International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon. (2010).

- Hanna L. & Adams M. Prevention of ovarian cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 20, 339–62 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch W. J. & Martinchick J. F. Oxidative damage to DNA of ovarian surface epithelial cells affected by ovulation: carcinogenic implication and chemoprevention. Exp Biol Med. 229, 546–52 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch W. J., Van Kirk E. A. & Alexander B. M. DNA damages in ovarian surface epithelial cells of ovulatory hens. Exp Biol Med. 230, 429–33 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senthil K., Aranganathan S. & Nalini N. Evidence of oxidative stress in the circulation of ovarian cancer patients. Clin Chim Acta. 339, 27–32 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert F. J., Raila J., Sehouli J. & Buscher U. Accumulation of selected carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol and retinol in human ovarian carcinoma ascetic fluid. Ann Nutr Metab 48, 241–5 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk R. T. et al. Urinary estrogen metabolites and their ratio among Asian American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 14, 221–6 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M., Rhodes C. J., Moncol J., Izakovic M. & Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 160, 1–40 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky N. I. & Johnson E. J. Carotenoid actions and their relation to health and disease. Mol Aspects Med. 26, 459–516 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L. Lee A. H., Su D. & Binns C. W. Fruit and vegetable consumption associated with reduced risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in southern Chinese women. Gynecol Oncol. 132, 241–7(2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushik A. et al. Intake of the major carotenoids and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 119, 2148–54 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiani F., Knutsen S., Singh P., Ursin G. & Fraser G. Dietary risk factors for ovarian cancer: the Adventist Health Study (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 17, 137–46 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung K. H. et al. Association of dietary vitamin A, carotenoids, and other antioxidants with the risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 14, 669–76 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer D. W., Kuper H., Harlow B. L. & Titus-Ernstoff L. Carotenoids, antioxidants and ovarian cancer risk in pre- and postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer. 94, 128–34 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann S. E., Moysich K. B. & Mettlin C. Intakes of selected nutrients and food groups and risk of ovarian cancer. Nutr Cancer. 39, 19–28 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield K. M. et al. Risk of ovarian carcinoma and consumption of vitamins A, C, and E and specific carotenoids: a prospective analysis. Cancer. 92, 2318–26 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vecchia C. Tomatoes, lycopene intake, and digestive tract and female hormone-related neoplasms. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 227, 860–3 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 14, 2531–5 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti C. et al. Cruciferous vegetables and cancer risk in a network of case-control studies. Ann Oncol. 23, 2198–203 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolahdooz F., Ibiebele T. I., van der Pols J. C. & Webb P. M. Dietary patterns and ovarian cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 89, 297–304 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong N. H. et al. Plasma carotenoids, retinol and tocopherol levels and the risk of ovarian cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 88, 457–62 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzlsouer K. J. et al. Prospective study of serum micronutrients and ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 88, 32–7 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvera S. A., Jain M., Howe G. R., Miller A. B. & Rohan T. E. Carotenoid, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E intake and risk of ovarian cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15, 395–7 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidoli E. et al. Micronutrients and ovarian cancer: a case-control study in Italy. Ann Oncol. 12, 1589–93 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifkins D. et al. Total and individual antioxidant intake and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 12, 211 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson C. A. et al. The role of antioxidants and vitamin A in ovarian cancer: results from the Women's Health Initiative. Nutr Cancer. 60, 710–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Holman C. D. & Binns C. W. Intake of specific carotenoids and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Nutr. 98, 187–93 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaffarino F. et al. Risk factors for ovarian cancer histotypes. Eur J Cancer. 43, 1208–13 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl W. & Sies H. Uptake of lycopene and its geometrical isomers is greater from heat-processed than from unprocessed tomato juice in humans. J Nutr. 122, 2161–6 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. S. Absorption, metabolism, and transport of carotenoids. FASEBJ. 10, 542–51 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. S., Swanson J. E., You C.-S., Edwards A. J. & Huang T. Bioavailability of carotenoids in human subjects. Proc Nutr Soc. 58, 155–62 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham S. A. Biomarkers in nutritional epidemiology. Public Health Nutr. 5, 821–7 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan L. et al. Validity and systematic error in measuring carotenoid consumption with dietary self-report instruments. Am J Epidemiol. 163, 770–8 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. T. & Green S. editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.0.2.The Cochrane Collboration; www.cochrane-handbook.org (2009). Date of access: 01/03/2010.

- Stroup D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 283, 2008–12 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 7, 177–88 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., & Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 315, 629–34 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]