Abstract

The purpose of this review was to demonstrate the definition of the original symptom (OS) and how it works in medical procedures as to the Sasang medicine based on the Jema Lee's Donguisusebowon (Longevity and Life Preservation in Eastern Medicine). OS is defined as the sum of all clinical information featured by an individual's intrinsic characteristics as Sasangin and health state prior to onset. It is the key factor in the clinical application of Sasang medicine including the diagnosis of constitutional type and Sasang symptomatology because the imbalance of metabolic functions of each Sasangin originates from that. The working principles of the OS and Sasang symptomatology can be summarized as follows. First, clinical information regarding cold or heat intolerance determines the cold or heat pattern of Sasang symptomatology. Another is the present worsening of the severity of Sasang symptomatology by one level as compared with that in the past. Symptoms prior to the onset worsen to a higher level of severity after any disorder breaks out. Finally, the treatment strategy and progress of each Sasangin are determined following the characteristics of the OS. Theoretical and clinical studies should be conducted to show the specific criteria for the diagnosis of Sasang symptomatology in the future.

Keywords: constitution, original symptom, review, Sasang medicine

1. Introduction

Sasang medicine (SM) is a personalized medicine dividing human beings into four constitutional types, based on their physiological and pathological chracteristics,1, 2 and presents a holistic approach based on the philosophical theory of four Virtues in Confucianism and clinical experiences in traditional Korean medicine.2, 3 Each of Sasangin or a constitutional type—that is, Taeyangin (Tae-Yang type), Taeeumin (Tae-Eum type), Soyangin (So-Yang type), or Soeumin (So-Eum type)—has its typical imbalance in the function of internal organ systems, and it accounts for the type-specific unique characteristics of energy–fluid or water–food metabolism.2

Original symptom (OS) was introduced by Jema Lee4 in his book, Donguisusebowon (Longevity and Life Preservation in Eastern Medicine), and it has been a key concept addressing the features of the innate symptoms of each constitutional type when compared with other tailored theories of complementary and alternative medicine.5 OS has physical and psychological symptoms that are useful for diagnosing constitutional types and their typical symptoms.

The possible roles of the OS in SM have been investigated through several clinical studies. For example, the symptoms (heat/cold preference, sleep sensitivity, appetite or digestive conditions, water-drinking tendencies, sweating, urination, or defecation6, 7, 8, 9, 10), appearance (body shape,10, 11, 12 body index mass,13, 14 voice,10, 15 or skin status,16, 17), and psychiatric characteristics6, 18, 19, 20 showed statistical significance to differentiate between constitutional types. However, how this OS fundamentally works in SM has not been well known.

The purpose of this review was to demonstrate the definition of OS and how it works in medical procedures as to the SM based on Jema Lee's work, Donguisusebowon (Longevity and Life Preservation in Eastern Medicine).

2. Definition of original symptoms

The Chinese letter 素 [sù] in Donguisusebowon4 means inborn element. Jema Lee4 reported a few brief cases in his book, and the reports started with the following expression: a patient originally had symptoms A, B, and C even before he became sick. This group of symptoms is called the OS. He suggested that each constitutional type has its own innate tendencies physically and mentally in SM.1, 2, 3 Sometimes, researchers prefer the term “ordinary symptom” to “original symptom.”21, 22 However, the word “ordinary” might not be sufficient to embrace the intrinsic concept of OS. The meaning of “innate” or “original” other than “plain” is more appropriate because OS comes from the imbalance in the function of the inner organ system.

Extensively, OS is defined as the sum of clinical information featured by an individual's intrinsic characteristics as Sasangin and health status prior to the onset—that is, OS consists of every single symptom prior to the onset. This occurs because each constitutional type has its own imbalance in metabolic functions or the type-specific unique characteristics of energy–fluid or water–food metabolism, and the uniqueness originates from the innate variation of function in the internal organ systems.1, 2, 3

Original illness is sometimes distinguished from the OS to emphasize the ill status of Sasangin.23 However, OS is comprehensively used to refer to both ill and good conditions in SM.

Time is a key factor to understand OS appropriately. The physiological symptoms of OS can differ from the pathological symptoms in Sasangin. In Sasangin, a person who had a few symptoms but did not require any treatments in the past, can become ill and show completely different symptoms at present. Physiological OS is the sum of clinical symptoms that do not need to be treated, whereas pathological OS is the sum of clinical symptoms that need to be treated. The latter is also called original illness. Generally, “original symptom” can be used to refer extensively to both physiological or pathological symptoms.

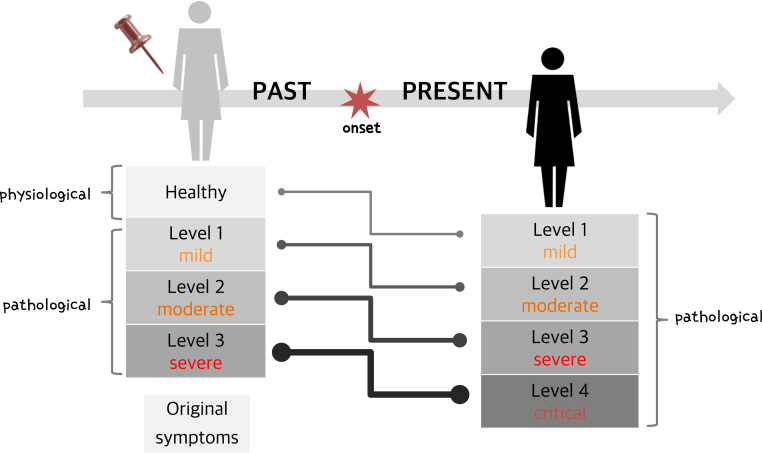

This meaning of OS is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Original symptom means the sum of clinical information featured by an individual's intrinsic characteristics as Sasangin and health status prior to the onset. Sasangin can be either in good or ill status throughout life. Original illness can specifically be used to refer to the pathological status prior to the onset. However, original symptom extensively expresses both physiological or pathological symptoms in Sasang medicine.

OS, original symptom; PS, present symptom.

3. Diagnostic principles of Sasangin and Sasang symptomatology: original symptoms

3.1. Diagnosis of Sasangin based on OS

Clinical procedures (Fig. 2) in SM start with the collection of a patient's clinical information. Based on the information, Sasangin diagnosis is the first step. In addition to appearance (facial features or body shape) or vocal features, OS is useful in identifying which of the following constitutional types—Tae-Yang, So-Yang, Tae-Eum, and So-Eum—should be applied, because every single symptom can indicate a functional imbalance of the internal organ system. For example, the functional condition of water–food metabolism can be evaluated from evacuation habits. Sweating and urination tendency are the best parameters to measure hyperactivity or hypoactivity of energy–fluid metabolism. The quality of sleep can be a good indicator of the psychiatric status in each constitutional type.

Fig. 2.

Clinical procedures in Sasang medicine consist of successive Sasangin and Sasang symptomatology Dx and treatment. Original symptom is the key factor in the clinical application of Sasang medicine.

Dx, diagnosis.

The key attribute is that the OS should be inherent. Practitioners should identify the earliest symptoms when they examine or evaluate a patient, as the present symptoms can differ from the past symptoms. From the obtained OS information, the relative hyperactivity and hypoactivity of metabolic functions in the four organ systems and then the constitutional type can be determined.2 For example, a woman used to have no appetite and difficulty in digesting food. In addition, she had much gas in the bowels. However, she might not have any issues that needed to be treated in the digestive system; she just felt uncomfortable from time to time. These symptoms can be interpreted as follows: the food-intake function is hypoactive, whereas the food-discharge function is hyperactive.3 Putting these interpretations together, her constitutional type could be diagnosed as the So-Eum type, or Soeumin. Even though she might not have any similar indication at the moment when a traditional Korean medicine practitioner examines her, the constitutional type can be identified with the inherent OS.

3.2. Diagnosis of Sasang symptomatology based on OS

3.2.1. First law

Clinical information regarding cold or heat intolerance in the past (i.e., OS) determines the cold or heat pattern of Sasang symptomatology. Sasang symptomatology means various distinguishing patterns/syndromes that each constitutional type shows in SM—that is, Tae-Yang type, So-Yang type, Tae-Eum type, or So-Eum type has its own unique symptomatology. However, all of these types have cold and heat patterns in common, and the identification of cold or heat pattern is the first step in the diagnosis of Sasang symptomatology.22, 24, 25, 26 OS plays an important role in this decision.

As shown in Fig. 3, a Sasangin can be diagnosed as a cold or heat pattern as for Sasang symptomatology. The clinical tendencies prior to the specific onset help physicians make that decision. For example, a female patient complains that she easily gets chills, and cold hands and feet, and cannot drink cold water at all. She has obvious indications of cold intolerance. Therefore, her Sasang symptomatology will be identified as a cold pattern. Even though she has a fever, seeks iced water, and even has sweating, she can be diagnosed as a cold pattern as for Sasang symptomatology. The opposite holds true as well. In the book Donguisusebowon, Jema Lee4 said that a patient with warm disease would have cold or heat tendencies prior to onset, and will have a cold or heat pattern of Sasang symptomatology, respectively, following the pre-onset tendency. Warm disease means an acute externally contracted disease caused by warm pathogens, with fever as the chief manifestation in traditional Korean or Chinese medicine.27

Fig. 3.

First law of Sasang symptomatology Dx: Cold or heat intolerance in the original symptom determines the cold or heat pattern of Sasang symptomatology. (Color annotation: blue indicates cold intolerance, red indicates heat intolerance, gray indicates no specific tendencies in cold or heat intolerance).

Dx, diagnosis.

3.2.2. Second law

The severity of the present Sasang symptomatology deteriorates by one level compared with the severity of OS. The severity of Sasang symptomatology is classified into mild, moderate, severe, or critical.28, 29, 30 For example, if a person originally showed a mild level of symptomatology prior to the onset, that person's condition usually worsens into a moderate level after a specific disease occurs. As described earlier, another person might have had a few uncomfortable symptoms that do not require treatment in the healthy status. If that person gets sick, then the severity of Sasang symptomatology goes into a mild level. This principle was clearly stated in Donguisusebowon as follows: when the OS was at a mild level, then the present symptoms become moderate; and when the OS is at a moderate level, then the present symptoms become severe (Fig. 4).4

Fig. 4.

Second law of Sasang symptomatology Dx: The severity of the present Sasang symptomatology deteriorates by one level as compared with the severity of the original symptom. That is, the symptoms prior to the onset worsen to a higher level after the disorder breaks out.

Dx, diagnosis.

4. Medical criteria for treatment and assessment: original symptoms

A case report of the Tae-Eum type was presented in Donguisusebowon,4 from which we can infer the strategic principle of treatment in SM. Herbal medication or acupuncture therapy should be decided following a cold or heat pattern prior to the onset. Although the patient has a heat pattern at present, practitioners should treat the patient with anti-cold herbs. This is because the patient's OS showed cold intolerance in the past. This means that OS also plays a critical role in the treatment process.

The most unaged symptoms improve at first throughout the treatment process. The oldest symptoms remain as they were for the longest time—that is, even after the present symptom of fever disappears, the OS could still remain unresolved. Therefore, OS is also used to assess and make decisions regarding the therapeutic progress of patients in SM. Practitioners assess the severity and decide until when the treatment should be continued. The final goal of the treatment is to resolve all the pathological symptoms prior to the onset. Fig. 5 illustrates the process of treatment and recovery in SM.

Fig. 5.

Treatment strategy and progress of each Sasangin are determined based on the characteristics of the original symptom.

To sum up, the treatment strategy and progress of each Sasangin are determined following the characteristics of the OS. However, this does not mean that the chief complaints are ignored in the process. It means that OS is as important as the chief complaints in SM.

5. Brief summary and further study

OS is defined as the sum of clinical information featured by an individual's intrinsic characteristics as Sasangin and health status prior to the onset. It is the intrinsic characteristics that originated from the typical imbalance in the function of internal organ systems and the key factor of the clinical procedures in SM. It helps practitioners identify the constitutional type and diagnose Sasang symptomatology. Physicians can detect Sasang symptomatology, measure its severity, and decide the treatment strategy by the characteristics of OS.

In the future, specific criteria for the diagnosis of Sasang symptomatology for each constitutional type, beyond Sasangin,8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 31, 32 should be studied theoretically and clinically.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through a grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (NRF-2014M3A9D7045482).

References

- 1.Lee J., Jung Y., Yoo J., Lee E., Koh B. Perspective of the human body in Sasang constitutional medicine. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):31–41. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y., Shin S., Hwang M. Morality and longevity in the viewpoint of Sasang medicine. Integr Med Res. 2015;4:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J., Pham D.D. Sasang constitutional medicine as a holistic tailored medicine. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):11–19. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J. Donguisusebowon. In: Dept. of Sasang Constitutional, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, ed. The manual book of Sasang constitutional medicine. 2nd ed. Seoul: Hanmibook; 2012. [In Korean]

- 5.Yoo J., Lee E., Kim C., Lee J., Lixing L. Sasang constitutional medicine and traditional Chinese medicine: a comparative overview. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:980807. doi: 10.1155/2012/980807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chae H., Lyoo I., Lee S., Cho S., Bae H., Hong M. An alternative way to individualized medicine: psychological and physical traits of Sasang typology. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:519–528. doi: 10.1089/107555303322284811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham D.D., Lee J., Lee M., Kim J. Sasang types may differ in eating rate, meal size, and regular appetite: a systematic literature review. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012;21:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S., Jang E., Lee J., Kim J. Current researches on the methods of diagnosing Sasang constitution: an overview. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):43–49. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee M., Bae N., Hwang M., Chae H. Development and validation of the digestive function assessment instrument for traditional Korean medicine: Sasang digestive function inventory. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:263752. doi: 10.1155/2013/263752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Do J., Jang E., Ku B., Jang J., Kim H., Kim J. Development of an integrated Sasang constitution diagnosis method using face, body shape, voice, and questionnaire information. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang E., Do J., Jin H., Park K., Ku B., Lee S. Predicting Sasang constitution using body-shape information. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:398759. doi: 10.1155/2012/398759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang E., Kim J., Lee H., Kim H., Baek Y., Lee S. A study on the reliability of Sasang constitutional body trunk measurement. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:604842. doi: 10.1155/2012/604842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S., Park S., Cloninger C.R., Kim Y., Hwang M., Chae H. Biopsychological traits of Sasang typology based on Sasang personality questionnaire and body mass index. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:315. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham D.D., Do J., Ku B., Lee H., Kim H., Kim J. Body mass index and facial cues in Sasang typology for young and elderly persons. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:749209. doi: 10.1155/2011/749209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang J., Ku B., Kim Y., Nam J., Kim K., Kim J. A practical approach to Sasang constitutional diagnosis using vocal features. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:307. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song H., Lee S., Park Y., Woo S. Quantitative Sasang constitution diagnosis method for distinguishing between Taeeumin and Soeumin types based on elasticity measurements of the skin of the human Hand. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):93–98. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung S., Park S., Chae H., Park S., Hwang M., Kim S. Analysis of skin humidity variation between Sasang types. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):87–92. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae H., Lee S., Park S., Jang E., Lee S. Development and validation of a personality assessment instrument for traditional Korean medicine: Sasang personality questionnaire. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:657013. doi: 10.1155/2012/657013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chae H., Park S., Lee S., Kim M., Wedding D., Kwon Y. Psychological profile of Sasang typology: a systematic review. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):21–29. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S., Kim M., Lee S., Kim J., Chae H. Temperament and character profiles of Sasang typology in an adult clinical sample. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:794795. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek Y., Kim H., Lee S., Ryu J., Kim Y., Jang E. Study on the ordinary symptoms characteristics of gender difference according to Sasang constitution. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2009;23:251–258. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim M., Lee H., Jin H., Yoo J., Kim J. Study on the relationship between personality and ordinary symptoms from the viewpoint of Sasang constitution and cold–hot. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2008;22:1354–1358. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi B., Ha K., Choi D., Kim J. Study on the “Dispositional symptoms (Dispositional diseases)” in 『Dongyi Suse Bowon』 [The discourse on the constitutional symptoms and disease] Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2007;21:1–9. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi Y., Kim K. Changes and distortions in the meaning of yin and yang, cold and heat, exterior and interior, deficiency and excessiveness in the constitutional medicine. J Sasang Constit Med. 1997;9:25–101. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S., Han S., Jang E., Kim J. Clinical study on the characteristics of heat and cold according to Sasang constitutions. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2005;19:811–814. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang E., Kim M., Baek Y., Kim Y., Kim J. Influence of cold and heat characteristics and health state in Sasang constitution diagnosis. J Sasang Constit Med. 2009;21:76–88. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the Western Pacific region. World Health OrganizationWHO; 2007. http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/PUB_9789290612483/en/. [Accessed 13 January 13, 2016].

- 28.Shin S., Lee E., Koh B., Lee J. Study on the development of diagnosis algorithm of Soeumin symptomology. J Sasang Constit Med. 2011;23:33–43. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin S., Lee E., Koh B., Lee J. Study on the development of diagnosis algorithm of Soyangin symptomatology. J Sasang Constit Med. 2011;23:294–303. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin S., Lee E., Koh B., Lee J. The study on the development of diagnosis algorithm of Taeeumin symptomology. J Sasang Constit Med. 2012;24:28–39. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang J., Kim Y., Ku B., Kim J. Recent progress in voice-based Sasang constitutional medicine: improving stability of diagnosis. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:920384. doi: 10.1155/2013/920384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J., Ku B., Kim Y., Do J., Jang J., Jang E. The concept of Sasang health index and constitution-based health assessment: an integrative model with computerized four diagnosis methods. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:879420. doi: 10.1155/2013/879420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]