Abstract

Background

Allometric scaling, which represents the dependence of biological traits or processes on body size, is a long-standing subject in biological science. However, there has been no study to consider heat loss to the ambient and an insulation layer representing mammalian skin and fur for the derivation of the scaling law of metabolism.

Methods

A simple heat transfer model is proposed to analyze the allometry of mammalian metabolism. The present model extends existing studies by incorporating various external heat transfer parameters and additional insulation layers. The model equations were solved numerically and by an analytic heat balance approach.

Results

A general observation is that the present heat transfer model predicted the 2/3 surface scaling law, which is primarily attributed to the dependence of the surface area on the body mass. External heat transfer effects introduced deviations in the scaling law, mainly due to natural convection heat transfer, which becomes more prominent at smaller mass. These deviations resulted in a slight modification of the scaling exponent to a value < 2/3.

Conclusion

The finding that additional radiative heat loss and the consideration of an outer insulation fur layer attenuate these deviation effects and render the scaling law closer to 2/3 provides in silico evidence for a functional impact of heat transfer mode on the allometric scaling law in mammalian metabolism.

Keywords: body heat transfer, scaling law of metabolism, theoretical analysis

1. Introduction

Allometric scaling, which represents the dependence of biological traits or processes on body size, is a long-standing subject in biological science. Extensive review articles1, 2, 3, 4, 5 indicate that the relevance of this subject spans a wide spectrum of biological fields, such as the principles of animal design and evolution of life.

Allometric scaling describes the basal metabolic rate (BMR) as a power function of body mass (m), i.e., BMR = amb, where a is a proportionality constant and b is the scaling exponent. Sarrus and Rameaux6 first presented the hypothesis that metabolic rate is limited by heat loss and linearly proportional to the surface area. An experimental study by Rubner7 confirmed a linear relationship in dogs. Considering that the surface area is proportional to m2/3, this implies that b = 2/3, which is referred to as the surface scaling law. A later study by Kleiber8 estimated BMR in a number of mammalian species and found that b is actually > 2/3 and closer to 3/4 which is now well-known as the 3/4 power scaling. Brody9 and Hemmingsen10 further claimed the validity of the 3/4 power scaling for a variety of organisms ranging from bacteria to elephants, including ectotherms and microorganisms. The empirical and theoretical basis for the 3/4-power law was extensively reviewed by Glazier.11

Theoretical investigations have attempted to provide a physical explanation for the empirical 3/4 power scaling. Among them, the fractal network theory (FNT)12 has attracted significant attention. FNT assumes that the resource distribution system in an organism has a self-similar fractal structure that is independent of body size. An optimal cascade path is sought for fluid transporting nutrients from the central reservoir to the finest tubes (e.g., capillaries). A detailed mathematical analysis yielded b = 3/4. Similar approaches13, 14 employing simpler assumptions have predicted the same scaling exponent. Consequently, FNT has been considered a reasonable explanation for a large number of empirical relationships found in the entire range of organisms including plants.

The universal 3/4 power scaling law, however, has been subjected to critical scrutiny. For example, the reliability of the data and interpretation was questioned, and it was argued that the basic assumptions behind the theoretical analysis may pose substantial limitations in generalizing the results.2, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 In particular, a major concern was that a large amount of empirical data yielded significant scatters in the scaling exponent between 1/2 and 1. These discrepancies have eventually led to a suspicion as to whether the metabolism of the entire organism can be correlated with a simple two-variable power relationship. As a result, alternative models of metabolic scaling have been proposed.11, 15, 20

Another strategy to reconcile the observed discrepancies in the scaling exponent is to narrow down the analysis to a smaller group of species that share some specific features of physics, geometry or biology. For example, White and Seymour17 considered only mammalian metabolism and reprocessed the existing BMR data to account for variations associated with body temperature, digestive state, and phylogeny. The refined data clearly showed that b = 2/3 rather than 3/4. These results are consistent with the findings of Heusner18 who performed a statistical analysis focusing on intraspecific comparisons. The revival of the surface scaling law demonstrates the important role of heat dissipation in mammalian metabolism.

Recently, there have been several papers to model and explain these phenomena effectively.20, 21, 22 In particular, Roberts et al22 proposed a new conceptual model (hereinafter, the RLP model) of mammalian metabolism based on the macroscopic energy balance in a body with heat generation. Experimental data from 10 mammalian species were carefully collected from the literature, so as to satisfy the requirements to be basal. Utilizing the physiological variables derived from collected data, a closed-form equation was derived for allometric scaling. The model, which was verified by the experimental data, showed that BMR is proportional to the surface-to-volume ratio (i.e., b = 2/3) and identified factors affecting the proportionality constant. This simple and informative model, however, had a few limitations. In particular, the assumption that the temperature difference between the core and surface is constant, aside from verifying its validity with the experimental data, poses several logical limitations. Specifically, since the surface temperature, which is the only external factor in the model, is constant, heat balance is determined by only internal factors. The neglect of variations in external factors, such as convective heat loss (possibly a strong function of length), inherently rules out size-dependence from the model.

In this study, we develop a new theoretical model of metabolism that is based on the RLP model, but considers two additional factors: heat loss to the ambient and an insulation layer representing mammalian skin and fur. Allometric scaling in mammals is examined numerically solving the full heat transport equation as well as by an analytic investigation of a simplified heat flow circuit. The results for mammalian metabolism are compared with those obtained by Roberts et al22 and the biological implications are discussed. Particular attention is paid to the significance of external heat transfer properties in the prediction of the allometric scaling law.

2. Methods

2.1. Physical and mathematical model

A simple conceptual model for allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism was developed. The original RLP model22 was modified to incorporate the interactions between BMR and external environmental factors. The major modifications were: (1) the geometry was changed from an ellipsoid to a cylinder with spherical ends; (2) an additional passive layer covering the main body was considered; and (3) heat loss to the ambient, which was not included in the RLP model, was considered.

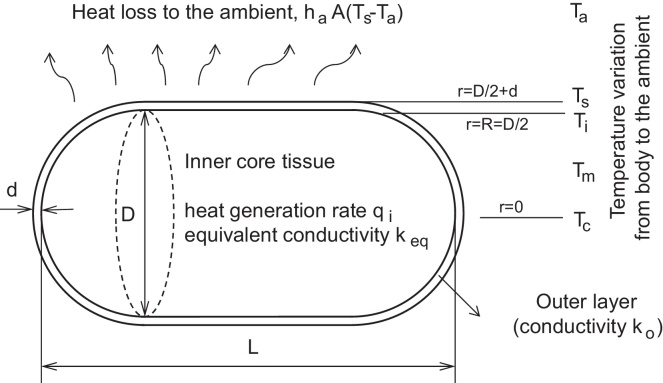

Fig. 1 depicts the configuration of a mammal in a thermoneutral state. Roberts et al22 chose a horizontally aligned prolate spheroid with an aspect ratio 5.4 as the best geometrical representation of animals in a thermoneutral posture. Unfortunately, no correlations of natural convection are available for this geometry in the literature. Therefore, an alternative geometry of a cylinder with spherical ends was adopted, for which a correlation for the heat transfer coefficient can be determined with good accuracy.23 For geometrical similarity, however, the ratio of volume V to surface area A is chosen to be identical to that of the ellipsoid, V/A = 0.2017D, where D is the diameter. This yields a fixed value of the length-to-diameter ratio, L/D = 1.724.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the model configuration for the heat transport from a mammalian body to the ambient.

The body is assumed to have a duplex structure: an inner core of tissue and an outer insulation layer representing the epidermis and fur. The metabolism is modeled by heat generation uniformly distributed within the inner core, at a volumetric heat generation rate, qi,

| (1) |

where Qgen and Qres denote the BMR and the respiratory heat loss, respectively. Roberts et al22 suggested a proportionality between the respiratory heat loss and BMR, Qres = 0.27Qgen, based on the collected experimental data, which is adopted in this study.

The fur layer plays an important role in energy balance in endotherms, but is an abstruse object for thermal modeling.24, 25 For simplicity, it is assumed that the outer fur layer is shallow (d/D <<1, where d is the thickness), thermally passive (no heat generation), and consists of a single material with a low conductivity ko. The insulation effect of this layer is represented by an effective heat transfer coefficient, ho = ko/d.

The thermoneutral state, which is an essential requirement for basal metabolism, is interpreted as the environment demanding a minimal energy requirement. In this study, the effects of wind and solar radiation were ignored, and the surface heat loss to the surroundings at a temperature Ta was assumed to be mainly by natural convection and radiation. We considered the steady heat transport equation in human tissue suggested by Pennes,26

| (2) |

where kt is the conductivity of the tissue, and q is the volumetric heat generation rate. HB represents the heat exchange by the blood circulation, and must be modeled. Following the RLP model, an effective heat transfer coefficient in a mammalian body is defined as:

| (3) |

where kb is the basal conductivity having an almost constant value of 0.5 W/mK,27 K is an artificially introduced conductivity representing the thermal mixing effect of blood flow, and R = D/2 is the radius of the cylinder. From the experimental data, Roberts et al22 found that h* is almost invariant around a mean value h* = 21.8W/m2K. Since kb is also constant, this implies that K depends on size (R). Following this, the net heat transfer through the core tissue and blood is described by a conductive heat transfer model,

| (4) |

with the equivalent heat conductivity defined as:

| (5) |

since K cannot be negative. The governing equation in the outer layer is also written as:

| (6) |

with the interface condition that the temperature is continuous across the inner core tissue to the outer layer. The boundary condition at the outer surface is written as:

| (7) |

where n denotes the unit normal outward vector to surface and Ts is the surface temperature.

Note that the present conductive heat transfer model in the core tissue produces a parabolic temperature profile, which is somewhat unrealistic, because the blood circulation tends to even out the temperature distribution within the core tissue. The present model is intended as a conservative case in which the effect of internal heat transfer on the metabolism is artificially overestimated, such that the possibility of an internal mechanism affecting the allometric scaling law can be assessed. As will be shown later, these effects were found to be minimal.

The heat transfer coefficient ha between the surface and the ambient environment is decomposed into two components: one due to natural convection hNC and the other due to radiation, hR, i.e.,

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

| (10) |

in which ka is the conductivity value of normal air, σ = 5.67 × 10−8W/m2K4 is the Stephan–Boltzmann constant, and ɛ is the surface emissivity. Temperature unit is Kelvin. While the emissivity of an animal skin varies among species, in general, it is known to be > 0.9 (0.97 for the human skin), hence ɛ = 0.95 is used in the model. For the geometry under study, the Nusselt number Nu, a dimensionless parameter measuring the relative intensity of natural convection to conduction, is available in the literature23:

| (11) |

where r = 9.5. Eq. (11) is applicable to a full range of length scales relevant in the present study, since it is derived by a power blending of the Nusselt number for laminar (Nul) and turbulent (Nut) convection:

| (12) |

| (13) |

where n = 1.07, NuD = 1.58, and . The Prandtl and Rayleigh numbers are defined as:

| (14) |

where g is the gravity and α, ν, and κ are the thermometric expansion coefficient, kinematic viscosity and thermal diffusivity of air, respectively.

2.2. Computational method

Eqs. (4–6) with a prescribed boundary condition (7) were numerically solved by FLUENT 6.3 (ANSYS, Canonsburg, PA). For the two-dimensional axisymmetric geometry, finite-volume quad elements of pave-type generated with an interval D/100 were employed. The computation model was validated for a test problem of conduction in a cylinder with a uniform heat generation. The acquired numerical solution showed excellent agreement with the analytic solution at an accuracy within the order of the truncation error at O(10–4).

Note that the numerical solution to Eqs. (4–7) requires the value of the volumetric heat generation qi (i.e., 0.73BMR/V). In practice, however, the objective of the study is to determine the corresponding BMR for a given body temperature. Therefore, the actual calculation procedure involves an iterative approach to obtain the correct BMR until the numerical solution for the body temperature matches the prescribed reference value within a tolerance of 0.01 °C. The reference body temperature is given by the correlation suggested by White and Seymour2:

| (15) |

where the units for temperature and mass are Celsius and kg, respectively.

Fig. 2 shows the typical temperature distribution in a mammalian body acquired from numerical computation. Since the two-dimensional temperature field varies both radially and axially, a proper way to define the equivalent body temperature is necessary. In the analysis by Roberts et al,22 the core temperature TC, which is the maximum temperature in the body, was used as the reference body temperature. However, there is little information on the detailed temperature distribution in a mammalian body. Furthermore, the present conductive model tends to overestimate the core temperature of the body. Therefore, the bulk mean temperature Tm, defined as the bulk-mass-weighted average temperature in the core tissue, is used as the reference body temperature in the subsequent analysis.

Fig. 2.

Temperature distribution in the inner core tissue of a mammal. m = 10 kg, ɛ = 0.95, d = 0 and Ta = 15°C. Here, A is the surface area, ha is the heat transfer coefficient between the surface and the ambient environment, Ts is the surface temperature, the ambient temperature is Ta, the core temperature is TC, Ti is the surface temperature of the inner core, and the body temperature is represented by Tm.

2.3. Analytic model

In addition to the numerical solutions, a simplified analysis model was also developed in order to derive a closed-form relationship between BMR and the external factors. Considering the uniform heat generation in the inner body, qi, adopted in this study, the net energy balance within the core tissue can be written as:

| (16) |

where Ti is a surface temperature of the inner core, hi is an equivalent heat transfer coefficient in the inner core, and is related to the equivalent conductivity defined in Eq. (5) as follows:

| (17) |

The constant C was determined from the numerical solutions. Based on the curve fit, the value was found to be nearly constant at 43.7, which was used in the analytic solution process.

Consequently, the heat flow from the body to the ambient is written as:

| (18) |

where the assumption of the shallow outer layer (d/D <<1) yields an almost constant surface area. Based on the heat flow circuit analysis, the total heat flow rate is expressed as:

| (19) |

where the overall heat transfer coefficient heq is given by:

| (20) |

For a given value of Tm − Ta, the solution to Eqs. (19), (20) provides BMR = Qgen = Q/0.73.

The standard properties of air as a function of temperature were used. The density of the inner tissue is constant, ρ = 1, 000 kg/m3. A basic assumption adopted for studying allometric scaling is that the ambient temperature Ta and the heat transfer coefficient of the outer layer ho, are independent of body mass. For several sets of (Ta, ho), BMR is calculated with mass varying in the range 10–3–104 kg.

3. Results

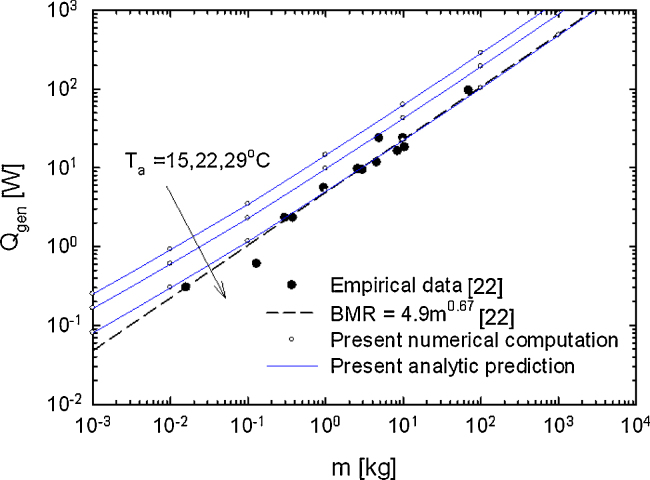

As a reference condition, we first consider a case with no radiation (ɛ = 0) and no insulation due to an outer layer (ho = ∞). Fig. 3 shows the allometric curves for three values of Ta = 15 °C, 22 °C, and 29 °C. The effects of the ambient temperature Ta (the thermoneutral temperature) are as expected: an increase in Ta results in reduced heat loss, thus requiring generation of a smaller amount of heat. The collected experimental data and the scaling function suggested by Roberts et al22 are also shown for comparison. For larger mammals, such as m ≥ 100kg, the present model predicts a result consistent with the RLP model at a slope of nearly 2/3. For smaller mammals, such as m < 1 kg, the slope of the curves deviates from 2/3 toward a somewhat lower value.

Fig. 3.

Scaling relation between basal metabolic rate (Qgen) and body mass (m) in mammals for the reference case with no radiation (ɛ = 0) and no outer layer for insulation (d = 0).

Fig. 4 depicts the allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism under a more realistic situation in which radiation heat loss is included. The additional radiative heat loss demands an increase in BMR, resulting in the allometric curves moving upward as compared to those in Fig. 3. In particular, the prediction at Ta = 29 °C shows a good match with the results of Roberts et al.22 In addition to the radiative heat loss, we examined the effect of the additional outer layer. Fig. 5 shows the same BMR scaling curves with an outer layer whose effective heat transfer coefficient is ho = 5 W/m2K. Since the typical effective conductivity of a fur layer is 0.02–0.06 W/m2K,25 the adopted value of ho represents an intensive insulation using a fur coat of 1 cm thickness. The slope of the curves now becomes almost constant at 2/3 throughout the mass range. In this case, the model with Ta = 15 °C shows excellent agreement with the scaling by Roberts et al.22

Fig. 4.

Scaling relation between basal metabolic rate (Qgen) and body mass (m) in mammals with radiative heat loss (ɛ = 0.95).

Fig. 5.

Scaling relation between basal metabolic rate (Qgen) and body mass (m) in mammals with an outer skin layer (ho = 5 W/m2K).

Fig. 6 shows the variations in the heq that are determined by the present model for all cases examined in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, plotted in terms of the body mass. Eq. (20) indicates that heq is a harmonic average of three components: (1) the equivalent heat transfer coefficient in the inner core hi; (2) the effective heat transfer coefficient of the outer layer ho; and (3) the external heat transfer coefficient ha. Of these three, heq is determined mainly by the smallest value.

Fig. 6.

Overall heat transfer coefficients versus body mass for all cases considered in this study.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of heat loss and insulation on allometric scaling law of metabolism using analytic and numerical methods. For this purpose, we proposed a theoretical model incorporating various external heat transfer parameters and additional insulation layers. The model equations were solved numerically and by an analytic heat balance approach.

Simulated results showed that the effects of the ambient temperature Ta (the thermoneutral temperature) are as expected: an increase in Ta results in reduced heat loss, thus requiring generation of a smaller amount of heat (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the slope of the allometric curves was found to be insensitive to variation in Ta. This implies that the ambient temperature has a minor effect on the scaling exponent.

For larger mammals, the present model predicts the slope of nearly 2/3. By contrast, the slope deviates from 2/3 toward a somewhat lower value for smaller mammals. Therefore, the external heat transfer model introduces discrepancies in the scaling exponent for smaller mammals. To identify the main cause of the deviation, we considered mammalian metabolism including radiation heat loss and found that the deviation in the slope of the curves is affected by the additional radiative heat loss, in that the slope for a smaller mass approaches 2/3 (Fig. 3, 4). The added insulation reduces heat loss to the ambient and subsequently leads to a decrease in BMR (Fig. 5).

As can be seen in heat flow model of Eq. (19), the scaling of BMR is determined primarily by three parameters: (1) the overall heat transfer coefficient, heq; (2) the surface area, A; and (3) the difference between the body and the ambient temperatures, Tm − Ta. Among these, the variations in body temperature (represented by Tm) are small; based on Eq. (15), the variation is only 1.4 °C within the full range of mass considered. Moreover, Ta was assumed to be independent of mass in this study. Therefore, the variation in the temperature difference Tm − Ta is insignificant. Secondly, the surface area, given the fixed surface-to-volume ratio under study, A ∝ m2/3 and is primarily responsible for the 2/3 scaling behavior. Therefore, the deviation in the slope from 2/3 is attributed to the dependence of heq on mass.

According to Eqs. (8–14), the natural convection component of ha is determined by the Nusselt number, which depends on the Rayleigh number, but at different power relations. For example, as Ra increases, Nu is initially independent of Ra (for Ra < 1), scales with Ra1/4 in the laminar convection regime, and with Ra1/3 when turbulent convection is dominant. Since Ra ∝ D3 and hNC ∼ Nu/D, this implies that hNC ∼ D−1 ∝ m−1/3 for very small Ra, hNC ∼ D−1/4 ∝ m−1/12 for moderate Ra, and hNC ∼ D0 ∝ m0 for large Ra. The open symbols shown in Fig. 6, which represent the cases in the absence of radiation and the outer layer, clearly show this trend in the transition of the slope. This is primarily responsible for the deviation in the slope from the 2/3 scaling shown in Fig. 3. Note that the slope does not recover −1/3 in the small mass limit because the Rayleigh number corresponding to m = 10–3 kg is still significant at 600, hence the slope is close to −1/6.

The effect of radiative heat loss on heq is examined. Eq. (10) indicates that the radiative heat transfer coefficient is independent of body size. For ɛ = 0.95, a typical value of hR is 5.4–6.2 W/m2K depending on the ambient temperature. By contrast, hNC decreases with body mass, ranging from 11.6 W/m2K at m = 10–3 kg to 1.84 W/m2K at m = 104 kg. Consequently, as body mass increases, the contribution from radiative heat loss becomes increasingly dominant, making heq less sensitive to body mass, as shown by the solid symbols in Fig. 6.

We will now discuss the effect of heat transfer in the inner core. In the present conductive body model, hi is explicitly given by Eq. (17), i.e., hi ∼ keqD/A. Considering the definition of equivalent conductivity in Eq. (5) (keq ∼ D), hi is nearly constant. The value of hi from our numerical computations was about 90 W/m2K or larger, which is an order of magnitude larger than ha. Consequently, the effect of hi, representing the heat transfer characteristics in the body tissue, on the allometric scaling is insignificant.

Finally, the effect of the outer insulation layer is expected to be similar to that of radiation. Since ho is considered to be independent of body mass, the influence on heq is determined solely by its absolute magnitude. For ho >> ha, the insulation does not affect the allometric scaling. For ho ∼ ha, however, the inclusion of the insulation layer considerably attenuates the dependence of ha on mass, hence heq is almost insensitive to body mass, as shown by the triangle symbols in Fig. 6. As a result, the surface scale dominates the allometric scaling, i.e., m 2/3.

Thus, consistent with the RLP model, our heat transfer model predicted the surface scaling law with a scaling exponent of 2/3.22 Additional effects contributed to slight modifications in the scaling exponent, but only toward a value smaller than 2/3. Considering the basic heat flow model, a possible explanation for the observation of a scaling exponent larger than 2/3 (thus supporting the existing 3/4 scaling law) may require a modification in the assumption that the surface-to-volume ratio is fixed. In other words, mammalian shape changes significantly with size. This effect will be investigated in our future study.

Although the present study investigated the physics of heat transfer and radiative loss from organisms, and what the implications of this are for allometric scaling, there were several limitations. First the configuration of a mammal for heat transfer analysis was conceptually simplified by a horizontally aligned prolate spheroid. Second, the present model is based on steady state assumption and thus did not produce transient solutions according to time because of cost-effective simulation for 147 model cases. However, these limitations were not expected to alter the main findings of this study greatly.

We propose a model to predict the allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism based on the heat transfer balance. Our model incorporated several additional effects associated with external heat loss parameters and examined their impact on the scaling exponent. A general conclusion is that our heat transfer model predicted the 2/3 surface scaling law, which is primarily attributed to the dependence of the surface area on body mass for a fixed surface-to-volume ratio. External heat transfer effects introduced deviations in the scaling law, mainly due to the natural convection heat transfer which becomes more prominent at smaller masses. This yielded a slightly modified scaling exponent smaller than 2/3. Additional radiative heat loss and consideration of an outer insulation fur layer, being relatively insensitive to size, attenuated these deviation effects and rendered the scaling law closer to 2/3. Based on these data, the effect of internal heat transfer within the mammalian body is unlikely to alter the observed scaling behavior significantly.

This study provides a general heat transfer model that incorporates various additional parameters, and thus is applicable to a general class of extended consideration, such as the effect of size-dependent surface-to-volume ratio. This effect will be considered in a future study.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Research Fund, Kumoh National Institute of Technology.

References

- 1.West G.B., Brown J.H. The origin of allometric scaling laws in biology from genomes to ecosystems: toward a quantitative underlying theory of biological structure and organization. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1575–1592. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White C.R., Seymour R.S. Allometric scaling of mammalian metabolism. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1611–1619. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagy K.A. Field metabolic rate and body size. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1621–1625. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suarez R.K., Darveau C.A. Multi-level regulation and metabolic scaling. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1627–1634. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speakman J.R., Krol E. The heat dissipation limit theory and evolution of life histories in endotherms—time to dispose of the disposable soma theory? Integr Comp Biol. 2010;50:793–807. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarrus R., Rameaux N. Mathématique appliquée à la physiologie. Bull Acad R Méd. 1839;3:1094–1100. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubner M. Über den eifluss der körpergrösse auf stoff- and kraftwechsel. Zeit Biol. 1883;19:536–562. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiber M. Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia. 1932;6:315–353. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brody S. Reinhold; New York: 1945. Bioenergetics and growth. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemmingsen A. Energy metabolism as related to body size and respiratory surfaces, and its evolution. Rep Steno Mem Hosp Cph. 1960;9:1–110. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glazier D.S. Beyond the ‘3/4-power law’: variation in the intra- and interspecific scaling of metabolic rate in animals. Biol Rev. 2005;80:611–662. doi: 10.1017/S1464793105006834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West G.B., Brown J.H., Enquist B.J. A general model for origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science. 1997;276:122–126. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.122. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/276/5309/122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banavar J.R., Maritan A., Rinaldo A. Size and form in efficient transportation networks. Nature. 1999;399:130–131. doi: 10.1038/20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bejan A. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. Shape and structure, from engineering to nature; pp. 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agutter P.A., Tuszynski J.A. Analytic theories of allometric scaling. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:1055–1062. doi: 10.1242/jeb.054502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolokotrones T., Savage V., Deeds E.J., Fontana W. Curvature in metabolic scaling. Nature. 2010;464:753–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White C.R., Seymour R.S. Mammalian basal metabolic rate proportional to body mass 2/3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4046–4049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heusner A.A. Energy metabolism and body size. I. Is the 0.75 mass exponent of Kleiber's equation a statistical artifact? Respir Physiol. 1982;48:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKechnie A.E., Wolf B.O. The allometry of avian basal metabolic rate: good predictions need good data. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:502–521. doi: 10.1086/383511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porter W.P., Kearney M.R. Size, shape and the thermal niche of endotherms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(Suppl. 2):19666–19672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907321106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartelt P.E., Klaver R.W., Porter W.P. Modeling amphibian energetics, habitat suitability, and movements of western toads, Anaxyrus (=Bufo) boreas, across present and future landscapes. Ecol Model. 2010;221:2675–2686. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts M.F., Lightfoot E.N., Porter W.P. A new model for the body size-metabolism relationship. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2010;83:395–405. doi: 10.1086/651564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raithby G.D., Hollands K.G.T. Natural convection. In: Rosenow W.M., Hartnett J.P., Cho Y.I., editors. Handbook of heat transfer. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. p. 4.1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter W.P., Munger J.C., Stewart W.E., Budaraju S., Jaeger J. Endotherm energetics: from a scalable individual-based model to ecological applications. Aust J Zool. 1994;42:125–162. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis L.B., Birkebak R. Convective energy transfer in fur. In: Gates D.M., Schmerl R.B., editors. Perspectives of biophysical ecology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1975. pp. 525–548. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pennes H.H. Analysis of tissue and arterial blood temperatures in the resting human forearm. J Appl Physiol. 1948;1:93–121. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1948.1.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valvano J.W., Cochran J.R., Diller K.R. Thermal conductivity and diffusivity of biomaterials measured self-heated thermistors. Int J Thermophys. 1985;6:301–311. [Google Scholar]