Abstract

Previous studies on the Sasang typology have focused on the differential diagnosis of each Sasang type with type-specific pathophysiological symptoms (TSPS). The purpose of this study was to elucidate the latent physiological mechanism related to these clinical indicators. We searched six electronic databases for articles published from 1990 to 2015 using the Sasang typology-related keywords, and found and analyzed 35 such articles. The results were summarized into six TSPS categories: perspiration, temperature preference, sleep, defecation, urination, and susceptibility to stress. The Tae-Eum and So-Eum types showed contrasting features with TSPS, and the So-Yang type was in the middle. The Tae-Eum type has good digestive function, regular bowel movement and defecation, high sleep quality, and low susceptibility to stress and cold. The Tae-Eum type has relatively large volumes of sweat and feels fresh after sweating; however, the urine is highly concentrated. These clinical features might be related to the biopsychological traits of the Tae-Eum type, including a low trait anxiety level and high ponderal and body mass indices. This study used the autonomic reactivity hypothesis for explaining the pathophysiological predispositions in the Sasang typology. The Tae-Eum and So-Eum Sasang types have a low threshold in parasympathetic and sympathetic activation, respectively. This study provides a foundation for integrating traditional Korean personalized medicine and Western biomedicine.

Keywords: autonomic reactivity hypothesis, Sasang typology, systematic review, type-specific pathophysiological symptoms (TSPS)

1. Introduction

The Sasang typology is traditional Korean personalized medicine based on the yin–yang philosophy and Confucianism along with the thousands of years of medical heritage in Korea.1, 2 The Sasang typology classifies humans into four types—Tae-Yang, So-Yang, Tae-Eum, and So-Eum—and provides type-specific clinical guidelines for prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation using acupuncture and medical herbs.2 The Sasang type of person is a clinical prototype explaining type-specific pathophysiological symptoms (TSPS), prognosis, and responses to type-specific intervention.3

Each Sasang type has typical temperament and physical characteristics.3 The So-Yang type is an extroverted, easygoing, and impulsive person, whereas the So-Eum type is an introverted, organized, and nervous person. Although the psychological characteristics of the Tae-Eum type is in between the So-Yang and So-Eum types, the Tae-Eum type has higher ponderal and body mass indices and greater chest and neck circumferences than the So-Yang and So-Eum types.3, 4 The Tae-Yang type is an originative, persistent, and independent person physically akin to the So-Eum type and psychologically akin to the So-Yang type.

There have been studies on the psychological,5, 6, 7 physical,3, 8 genetic,9, 10 and pathophysiological symptoms8 of each Sasang type, and these have shown that the biopsychosocial profile of each Sasang type is stable across the lifespan using the Sasang Personality Questionnaire3 and the ponderal index.4 The biopsychological distinction between Sasang types may be related to specific mechanisms, such as extroversion and neuroticism,5 novelty seeking and harm avoidance,6, 11, 12 behavioral activation and inhibition systems (neurotransmitters),3, 12, 13 hypothalamic activity,4 basal metabolic rate,4 thyroid activity,4 and the autonomic nervous system.14, 15, 16 The detailed mechanisms can be examined through macroscopic system biology.9, 10

The Sasang TSPS are type-specific clinical symptoms in digestion, sweat, sleep, urination, and defecation, and they are considered important clinical indices for diagnosis, intervention, and prognosis along with the biopsychological traits of each Sasang type.3, 8, 17 As for the underlying physiological systems, the Tae-Yang type is a person with strong sympathetic activation and weak anabolism and energy-storing characteristics, whereas the Tae-Eum type has strong anabolism and energy-saving and weak sympathetic activation. The So-Yang type has strong intake and digestion and weak waste discharge; by contrast, the So-Eum type has strong waste discharge and weak intake and digestion.3

Although TSPS and their related clinical symptoms are pivotal for the clinical application of the Sasang typology, previous studies have focused on finding clinical symptoms for differential diagnosis between Sasang types18 rather than examining the fundamental pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these differences.3 The pathophysiological mechanism is crucial for understanding Sasang typology; however, previous sporadic studies emphasizing clinical conditions for Sasang type discrimination have inevitable limitations.15, 19

For that reason, we systematically reviewed the TSPS of the Sasang typology by searching six electronic databases for articles published during the past 25 years, and analyzed them to elucidate the underlying Sasang type-specific physiological mechanisms. Jema Lee's Longevity and Life Preservation in Eastern Medicine2 and clinical studies8, 15, 19 consider five categories of TSPS—perspiration, sleep, digestive function, urination, and defecation—to be clinically important. In the present study, we incorporated three more proven TSPS categories: temperature preference, susceptibility to stress or fatigue, and physical characteristics. For the analysis, we integrated previous reviews on digestive function,8 body shape,3 and temperament6, 11 because satisfactory systematic reviews had been published elsewhere.

This study aims to provide a foundation for understanding the Sasang typology and its type-specific clinical symptoms, and contribute to establishing integrative medicine incorporating traditional Korean personalized medicine and Western biomedicine.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Search strategy and data sources

We searched the following six electronic databases in either Korean or English: PubMed (www.pubmed.org), DBpia (www.dbpia.com), the Research Information Service System (RISS, www.riss4u.net), the Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal (www.koreantk.com), the Korean Studies Information Service System (kiss.study.com), and National Discovery for Science Leaders (www.ndsl.kr).

The keywords entered for screening were “Sasang,” “Sasang typology,” “Sasang constitution,” and “Sasang classification” in Korean and English, and we extracted only articles published from 1990 to 2015. We excluded duplicate or irrelevant articles and then manually searched additional articles from our departmental files and relevant journals.

2.2. Article selection and data extraction

2.2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles presenting specific and detailed Sasang TSPS in perspiration, sleep, defecation, urination, temperature preference, and response to stress were included. Sasang TSPS in digestive function,8, 17 body shape,1, 3, 8 and temperament6, 11 were also included from previous systematic reviews.

We excluded articles with type-specific interventions or their therapeutic effects, hypotheses, clinical cases, or type-specific diagnostic methods. Reviews on medical classics, textbooks, or translated texts were also excluded. Only articles with detailed, specific, clear, and objective measures on Sasang type-specific clinical symptoms were analyzed.

2.2.2. Data extraction

All selected articles were independently reviewed by two authors (Y.R.H. and H.C.), and data from the articles were extracted based on the predefined criteria. Data pertaining to demographic characteristics, such as the number of participants, sex distribution, description of the participants, and mean age, were collected. The Sasang-type classification method and the prevalence of each Sasang type were also provided. Significant differences in TSPS between the Sasang types in terms of perspiration, sleep, defecation, urination, stress response, and temperature preference were organized for comparison.

2.2.3. Data analysis

Significant differences in pathophysiological symptoms between the Sasang types were obtained through the following steps. First, the articles were categorized into groups depending on the symptom: perspiration, sleep, defecation, urination, response to stress or fatigue, and temperature preference. We then extracted and organized the major features of the type-specific clinical symptoms reported in the articles. Lastly, we selected repeatedly and reliably reported clinical symptoms for each Sasang type and elucidated the latent physiological and pathological mechanisms for the Sasang typology.

3. Results

3.1. Article selection

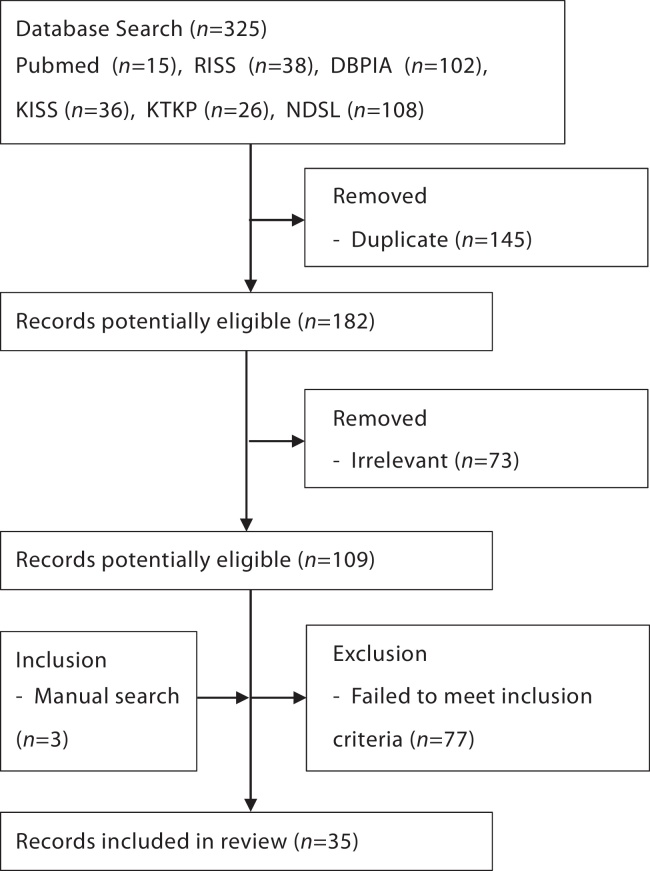

There were 325 potentially relevant articles identified from the six databases, and 145 were removed as duplicates. Three articles were added from the manual search, and 77 articles were excluded because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. As a result, 35 articles were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Data extraction process of the current review.

KISS, Korean Studies Information Service System; KTKP, Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal; NDSL, National Discovery for Science Leaders; RISS, Research Information Service System.

3.2. Demographic characteristics of participants

The demographic characteristics of the participants and the details of the Sasang type classification are described in Table 1. Most studies were conducted with Koreans, except for two, which employed Vietnamese and Japanese participants. Seventeen articles dealt with clinical patients, nine with healthy or nonclinical participants, and another nine with a mixed group of participants. Eleven articles incorporated only one sex, seven employed women, and four employed men.

Table 1.

Demographic features of the articles reviewed in this study

| References | Demographic features |

Sasang-type classification |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (male, female) | Characteristics of participants | Age (y) | Method | Prevalence (TY, SY, TE, SE) | |

| Kim K et al (2010)20 | 338 (307, 295) | Healthy individuals | 20–29, 60–69 | Clinical specialist | 0, 131, 257, 214 |

| Park GS et al (2003)21 | 305 (0, 305) | Female college students | n.a. | QSCC II | 0, 33, 51.6, 15.4 (%) |

| Choi JY et al (2002)22 | 504 (214, 290) | Outpatients | 39.9 | Clinical specialist, drug response | 8, 125, 148, 223 |

| Baek YH et al (2010)23 | 171 (171, 0) | Outpatients | 10–80 | Clinical specialist | 0, 46, 70, 55 |

| Kim HJ et al (2009)24 | 1,523 | Outpatients | 9–85 | Clinical specialist, drug response | 0, 514, 603, 406 |

| Kim TY et al (2013)25 | 488 (0, 488) | Female college students | n.a. | QSCC II | 0, 112, 59, 168 |

| Jang ES et al (2009)26 | 315 (0, 315) | Outpatients | 10–80 | Clinical specialist | 0, 109, 124, 82 |

| Shin SW et al (2013)27 | 9,213 (4,750, 4,463) | Health-screening population, obesity patients | 45.6 ± 11.1 | QSCC II, clinical specialist | 0, 2974, 4281, 1958 |

| Choi JY et al (2002)28 | 504 (214, 290) | Outpatients | 39.9 | Clinical specialist | 8, 125, 148, 223 |

| Kwon JH et al (2013)29 | 170 (62, 108) | Healthy individuals, Vietnamese | 20–80 | Clinical specialist | 0, 51, 62, 57 |

| Lee SH et al (2005)30 | 1,083 (421, 662) | Outpatients | n.a. | Clinical specialist with chart review* | 3, 288, 548, 244 |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | 1,241 (476, 765) | Outpatients | 10–80 | Clinical specialist | 0, 389, 541, 311 |

| Jang ES et al (2007)32 | 418 (168, 250) | Outpatients | 13–75 | Clinical specialist, drug response | 0, 126, 191, 101 |

| Choi JR et al (2003)33 | 610 (258, 352) | Outpatients | 39.1 (10s–80s) | Clinical specialist, drug response | 12, 137, 182, 279 |

| Kim YY et al (2011)34 | 2,629 (973, 1,656) | Outpatients | > 10 | Clinical specialist, drug response | 0, 885, 1061, 683 |

| Park HJ et al (2006)35 | 1229 (529, 700) | Outpatients | n.a. | Clinical specialist with chart review | Male (11, 261, 207, 50), female (3, 104, 154, 439), total (TY+TE = 375, SY+SE = 854) |

| Kim SH et al (2005)36 | 30 (30, 0) | Healthy individuals | 20s | QSCC II, body measures, face measures, clinical specialist | 0, 10, 10, 10 |

| Kim YY et al (2012)37 | 144 (68, 76) | Healthy individuals, Japanese | 24.5 | Arbitrary tool by KIOM† | 0, 53, 28, 63 |

| Sok S et al (2009)38 | 405 (103, 302) | Healthy individuals | > 65 | Arbitrary tool by KHU‡ | 0, 134, 137, 134 |

| Lee SK et al (1996)39 | 196 (107, 86) | Health-screening population | 42.84 (male: 43.45; female: 42.06) | QSCC I, clinical specialist | 0, 28, 110, 58 |

| Choi JY (2004)40 | 1,229 (529, 700) | Outpatients | 38.6 (7–88) | Clinical specialist with chart review | 14, 365, 361, 489 |

| Jung SO et al (2009)41 | 99 (69, 30) | College students | n.a. | QSCC II | Male (0, 14, 17, 38), female (0, 9, 6, 15) |

| Kim YM et al (2014)42 | 109 (0, 109) | Healthy individuals | TE: 57.5; SE: 56.1 (50–70) | Arbitrary tool by KIOM§ | 0, 0, 63, 46 |

| Cho JH et al (2007)43 | Experimental group: 72 (27, 45); healthy control: n.a. | Outpatients with chronic fatigue, without any physical or mental problems; healthy control | Experimental group: 20–66; healthy control: n.a. | QSCC II | Experimental group: n.a., 24, 14, 20, [n.a., 41.4, 24.1, 34.5 (%)]; healthy control: 0, 29.1, 46.9, 24.0 (%) |

| Yoo JH et al (2003)44 | 258 (219, 39) | College students | 27 (19–48) | QSCC II, clinical specialist | 0, 80, 87, 91 |

| Choi EY et al (2008)45 | 226 (0, 226) | Female college students | n.a. | Modified QSCC II | 9, 28, 45, 18 (%) |

| Cha NH et al (2005)46 | 825 (825, 0) | Industrial workers | 36.5 (23–57) | QSCC II, clinical specialist | 0, 219, 315, 291 |

| Seo BY et al (2003)47 | 479 (479, 0) | Laborers in workplace, health-screening population | n.a. | Arbitrary questionnaire, clinical specialist | 0, 136, 188, 155 |

| Kim K et al (2013)48 | 63 (fatigue group: 12, 20; nonfatigue group: 12, 19) | Healthy individuals | Fatigue group: 48.81 ± 5.12; nonfatigue group: 49.06 ± 5.40 (40–60) | Arbitrary tool by KIOM,§ clinical specialist | Fatigue group: 0, 10, 8, 14; nonfatigue group: 0, 15, 7, 9; total: 0, 25, 15, 23 |

| Shin EJ et al (2004)49 | 51 (0, 51) | Middle-aged women, outpatients with fatigue | 46.3 (40–60) | QSCC II | 0, 12, 13, 26 |

| Lee AY et al (2013)50 | 73 (0, 73) | Healthy postpartum women | 31.45 ± 3.86 | Arbitrary questionnaire, clinical specialist | 0, 22, 33, 18 |

| Jeon EY et al (1992)51 | 87 (46, 41) | Outpatients | 50 (24–78) | Arbitrary questionnaire | 0, 27, 33, 27 |

| Chang JY et al (2012)52 | 30 (19, 11) | Oriental medicine students with higher-than-average stress | 23.47 | QSCC II | 0, 8, 13, 9 |

| Kim KB et al (2001)53 | 112 (52, 60) | Hemodialysis patients | 52.05 | QSCC II | 0, 43, 39, 30 |

| Pham DD et al (2015)54 | 550 (297, 253) | Healthy individuals | 20–49 | Arbitrary tool by KIOM§ | Male (0, 57, 62, 59), female (0, 40, 46, 40) |

No specific adverse events related to the Sasang type-specific medication.

Constitution-diagnosing tool developed by KIOM in 2011.

Constitution-diagnosing tool developed by Department of Sasang, Oriental Medical School (KHU) in 1996.

Sasang Constitutional Analytical Tool developed by KIOM.

KHU, Kyung Hee University; KIOM, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine; n.a., not available; QSCC, Questionnaire for Sasang Constitution Classification; SE, So-Eum; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

With regard to the Sasang type classification, various tools and methods were used, including the Questionnaire for Sasang Constitutional Classification (QSCC) I and II, the modified QSCC, the Sasang Constitutional Analytical Tool, diagnosis by a clinical specialist, Sasang type-specific medication response, measurements of face and body shape, and arbitrary measures by the authors. Twenty-two studies used only one classification method, and 13 used a combination of two or more methods for diagnosis. Only six articles showed pathophysiological clinical symptoms of the Tae-Yang type.

3.3. Perspiration

Fifteen articles showed Sasang typology-related characteristics in perspiration (Table 2).20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 39, 40, 41, 42, 54 As for the amount of sweat, nine articles showed that the Tae-Eum type tends to sweat excessively,20, 22, 24, 27, 29, 31, 32, 39, 41 and one article showed that the Tae-Eum or So-Yang type has a larger amount of sweat than the So-Eum type.40 In addition, seven articles reported that the So-Eum type sweats less than the others,22, 24, 27, 31, 32, 39, 41 and one article showed that the So-Yang type sweats only a little.29 However, two articles reported that the So-Yang type sweats moderately,24, 32 while another article showed that it is the So-Eum type that sweats moderately.29

Table 2.

Sasang type-specific clinical features with perspiration

| References | Amount of sweat | Feeling after sweat | Pathological features of sweat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kim K et al (2010)20 | Overall: excessive [TE > SY > SE‡ (39.7%, 28%, 14.5%)]; 20s: excessive [TE > SY > SE‡ (38.1%, 24.6%, 7.8%)]; 60s: N.S. |

N.S. | n.a. |

| Choi JY et al (2002)22 | Excessive [TE > SE, SY > SE‡ (TE:45.1%, SY:40.4%, SE:17.8%)], less [SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:46.7%, SY:30.3%, TE:23.3%)] | Fresh [TE > SE, SY > SE‡ (TE:37.2%, SY:43.8%. SE:20.0%)], fatigue [SE > TE, SE > SY‡ (SE:43.7%, TE:24.5%, SY:21.3%)] | Sweats less overall but gets cold sweats in poor condition, then the physical condition gets worse [SE, SY, TE, TY* (SE:32.7%, SY:20.8%, TE:16.4%, TY:12.5%)]; feels hot overall, sweats more than others, and sweats at night when in poor health [SY, TE, SE, TY* (SY:24.8%, TE:18.4%, SE:10.3%, TY:0%)] |

| Kim HJ et al (2009)24 | Excessive [TE > non-TE‡ (TE:36.4%, SY:25.0%, SE:15.5%)], moderate [SY > non-SY‡ (SY:35.4%, SE:32.5%, TE:28.4%)], less [SE > non-SE‡ (SE:40.4%, SY:29.7%, TE:28.6%)] | Fresh [TE > non-TE‡ (TE:47.2%, SY:36.8%, SE:25.1%)], fatigue [SE > non-SE‡ (SE:41.1%, SY:29.4%, TE:21.4%)] | Sweats when having a meal (TE > non-TE‡) |

| Jang ES et al (2009)26 | n.a. | n.a. | SF-36 [difference between normal and abnormal sweating (SE > non-SE)] |

| Shin SW et al (2013)27 | Excessive [TE, SY, SE‡ (60.9%, 52.3%, 34.5%)], less [SE, SY, TE‡ (65.5%, 47.7%, 39.1%)] |

n.a. | n.a. |

| Kwon JH et al (2013)29 | Excessive [TE > SY, TE > SE‡ (TE:42%, SY:34.6%, SE:23.5%)], moderate [SE > TE, SE > SY‡ (SE:47.8%, TE:34.8%, SY:17.4%)], less [SY > SE, SY > TE‡ (SY:55.0%, SE:25.0%, TE:20%)] | n.a. | n.a. |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | Excessive [TE > SY > SE‡ (39.6%, 25.5%, 14.1%)], less [SE > SY > TE‡ (45.1%, 27.3%, 19.3%)] | Fresh [TE > SY > SE‡ (49.8%, 37.5%, 24.1%)], fatigue [SE > SY > TE‡ (45.6%, 31.4%, 22.1%)] | Sweats during meals [TE > SY > SE† (TE:24.4%, SY:19.9%, SE:13.5%)] |

| Jang ES et al (2007)32 | Excessive [TE > SY, TE > SE‡ (TE:40.8%, SY:28.1%, SE:13.5%)], moderate [SY, TE, SE‡ (SY:43.8%, TE:36.1%, SE:32.3%)], less [SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:44.8%, SY:21.9%, TE:14.7%)] | Refreshed [TE > SY > SE‡ (36.7%, 33.9%, 14.6%), fatigue [SE > TE > SY‡ (SE:37.1%, TE:22.0%, SY:16.1%)] | n.a. |

| Kim YY et al (2011)34 | n.a. | n.a. | Symptomatic involvement in perspiration during physical exhaustion [TE > non-TE‡ (TE:16.5%, SY:9.9%, SE:8.5%)] |

| Park HJ et al (2006)35 | Less (SY + SE > TY + TE) | Not fresh (SY + SE > TY + TE) | Sweats at night (TY + TE > SY + SE), breaks out in a cold sweat during physical exhaustion (SY + SE > TY + TE), sweats during meals (TY + TE > SY + SE) |

| Lee SK et al (1996)39 | Excessive (TE > SY, TE > SE‡), less (SE > TE, SE > SY‡) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Choi JY, (2004)40 | Excessive (TE > SE, SY > SE) | Fresh (TE > SE, SY > SE) | Sweats during meals (TE > SE, SY > SE), sweats at night (TE > SE, SY > SE), breaks out in a cold sweat during physical exhaustion (SE > TE, SE > SY) |

| Jung SO et al (2009)41 | A lot [TE > SY, TE > SE* (TE:69.6%, SY:26.1%, SE:18.9%)]; not a lot [SE > SY, SE > TE* (SE:56.6%, SY:30.4%, TE:13%)]; skin humidity variation (after forced perspiration – before forced perspiration): TE > SE, TE > SY† |

Refreshed [TE > SY, TE > SE* (TE:69.6%, SY:26.1%, SE:18.9%)], tired [SE > SY, SE > TE* (SE:56.6%, SY:30.4%, TE:13%)], not really tired [SY > SE, SY > TE* (SY:43.5%, SE:24.5%, TE:17.4%)], refreshed after sweating when feeling unwell [TE > SY, TE > SE* (TE:60.9%, SY:34.8%, SE:17.0%)] |

Experiences more cold sweats when the sickness worsens, although normally does not perspire a lot [SE > TE* (SE:45.3%, SY:30.4%, TE:8.7%)] |

| Kim YM et al (2014)42 | Perspiration on forehead after induced perspiration (TE > SE*) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Pham DD et al (2015)54 | Local sweat rate at chest and back after 7 and 5 min of exercise, male (TE > SY, TE > SE, respectively); local sweat rate at chest and back after 5 and 6 min of exercise, female (TE > SY, TE > SE, respectively); whole-body sweat rate after 1 min of exercise, female (TE > SE), whole-body sweat rate in the middle stage of exercise, female (TE > SY, TE > SE) |

n.a. | n.a. |

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

n.a., not available; N.S., not significant; SE, So-Eum; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

There were seven articles available with significant differences between the Sasang types in terms of the feeling after sweating.22, 24, 31, 32, 35, 40, 41 Six articles reported that mainly the Tae-Eum type feels fresh after sweating, followed by the So-Yang and So-Eum types.22, 24, 31, 32, 40, 41 In particular, one article reported that the Tae-Eum type feels refreshed after sweating when feeling uncomfortable.41 Five articles showed that the So-Eum type tends to feel fatigue after sweating, followed by the So-Yang and Tae-Eum types.24, 31, 32, 40, 41 One article revealed that the So-Yang and So-Eum types do not feel fresh after sweating compared with the Tae-Yang and Tae-Eum types,35 and another found that the So-Yang type does not become tired after sweating.41

Eight articles dealt with various pathological features of sweating,22, 24, 26, 31, 34, 35, 40, 41 and detailed symptoms are presented in Table 2.

3.4. Preferred temperature

Nine articles measured temperature preference or preference for warm or cold food and drinks (Table 3).24, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 36, 37, 40 Eight articles reported that the So-Eum type prefers warmth over cold and feels relatively cold and the Tae-Eum type prefers cold than warmth.24, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 36, 37 Three articles additionally mentioned that the So-Yang type has a stronger preference for cold than the So-Eum type.30, 32, 40

Table 3.

Sasang type-specific clinical features in temperature preference

| References | Preference for heat (aversion to cold) | Preference for cold (aversion to heat) | Temperature of hands or feet | Preferred temperature of drinking water or food |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim HJ et al (2009)24 | SE > TE, SE > SY‡ (SE:53.7%, SY:44.8%, TE:39.1%) | TE > SY, TE > SE‡ (TE:41.3%, SY:32.2%, SE:20.4%) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Kwon JH et al (2013)29 | SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:52.0%, SY:28.0%, TE:20.0%) | TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE:45.5%, SY:31.8%, SE:22.7%) | Hands: warm [TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE:43.3%, SY:32.0%, SE:24.7%)], cold [SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:64.7%, SY:23.5%, TE:11.8%)]; feet: warm [TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE:46.6%, SY:30.7%, SE:22.7%)], cold [SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:44.8%, SY:31.0%, TE:24.1%)] |

Warm [SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:40.8%, SY:35.5%, TE:23.7%)], cold [TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE: 46.6%, SY: 29.3%, SE:24.1%)] |

| Lee SH et al (2005)30 | SE > non-SE‡ (aversion to heat, RDA=–0.5) | TE > SE, SY > SE‡ (RDA=0.1) | Warm [TE > non-TE‡ (RDA=0.2)], cold [SE > non-SE‡ (RDA=0.2)] | Warm [SE > non-SE‡ (RDA=0.5)], cold [TE > SE, SY > SE‡ (RDA=0.1)] |

| Shin SW et al (2013)27 | SE, SY, TE‡ (42.9%, 25.3%, 22.9%) | TE, SY, SE‡ (31.2%, 26.4%, 13.5%) | Cold [SE, SY, TE‡ (41.1%, 18.9%, 18.9%)] | Cold [TE, SY, SE‡ (52.4%, 48.2%, 26.8%)] |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:53.6%, SY:40.6%, TE:37.9%) | TE > SY, TE > SE‡ (TE:35.8%, SY:31.8%, SE:15.6%) | Hands: warm [TE, SY, SE‡ (52.3%, 41.5%, 37.7%)], cold [SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:33.2%, SY:24.5%, TE:12.3%)]; feet: warm [TE, SY, SE‡ (43.8%, 35.3%, 31.3%)], cold [SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:37.1%, SY:28.6%, TE:18.8%)] |

Warm [SE > SY, SE > TE‡ (SE:45.3%, SY:29.4%, TE:28.5%)], cold‡ [SY, TE, SE (49.5%, 49.2%, 37.3%)] |

| Jang ES et al (2007)32 | SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:50.0%, SY:38.0%, TE:36.1%) | TE > SE, SY > SE† (TE:27.2%, SY:25.6%, SE:12.0%) | Cold [SE > TE, SE > SY‡ (SE:50.0%, TE:30.4%, SY:28.5%)] | Warm [SE > SY > TE† (SE:58.1%, SY:44.1%, TE:42.1%)], cold [TE > SE, SY > SE† (TE:57.9%, SY: 55.9%, SE:41.8%)] |

| Kim SH et al (2005)36 | Feels relatively cold (SE > non-SE) (significant at 27 °C, humidity 50%) | Feels relatively hot (TE > non-TE) (significant at 27 °C, humidity 50%) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Kim YY et al (2012)37 | n.a. | n.a. | Cold [SY > non-SY* (SY:79.2%, SE:74.6%, TE:46.4%)] | Cold [TE > SY > SE† (TE:89.3%, SY:81.0%, SE:64.2%)] |

| Choi JY, (2004)40 | SE > TE, SY > TE | TE > SE, SY > SE | Cold (SE > TE, SE > SY) | Cold (TE > SE, SY > SE) |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

n.a., not available; RDA, relative discrimination ability; SE, So-Eum; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

There were seven studies on the temperature of the extremities (e.g., hands or feet).27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 37, 40 Three studies showed that the Tae-Eum type has warmer hands or feet than other types.29, 30, 31 In addition, six studies reported that mainly the So-Eum type has cold hands or feet,27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 37 although one of them found that the So-Yang type also does.37

As for the preferred temperature of drinking water or food, there were seven studies.27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 37, 40 Four studies showed that the So-Eum type prefers warm water or food.29, 30, 31, 32 Six studies showed that the Tae-Eum type prefers cold water or food,27, 29, 30, 32, 37, 40 and five of them mentioned that the So-Yang type has a stronger preference for cold water or food than the So-Eum type.27, 30, 32, 37, 40 In addition, one study reported that the preference for cold water or food decreases in this order: So-Yang, Tae-Eum, and So-Eum.31 However, there were relatively small and nonsignificant differences.

3.5. Sleep

Three studies identified sleeping-related differences between the Sasang types using objective measures (Table 4).25, 33, 38 One study that used a part of the Sasang Constitutional Analytical Tool reported that the So-Eum type tends to dream a lot, the Tae-Yang type has difficulty with going to sleep and frequently awakens, and the Tae-Eum type tends to sleep less.33 Another study, which used Sleep Scale A, reported that the Tae-Eum type presents a higher score of sleep state, which means it has a better sleep state than others.38 Yet another study, which used the Graphics Rating Scale, showed that satisfaction with sleep decreases in this order: Tae-Eum, So-Yang, and So-Eum.38

Table 4.

Sasang type-specific clinical features in sleep

| References | Sleeping patterns | Feeling after sleeping |

|---|---|---|

| Kim TY et al (2014)25 | n.a. | PSQI (N.S.) |

| Choi JR et al (2003)33 | [Questionnaire]§ Dreams: a lot [SE > non-SE‡ (SE:24.7%, TE:12.1%, SY:8.0%, TY:0%)], less [non-SE > SE* (TY:41.7%, SY:38.0%, TE:30.2%, SE:21.9%)] Has difficulty falling asleep, wakes frequently [TY > non-TY*, non-SY > SY* (TY:75.0%, SE:41.2%, TE:37.4%, SY:28.7%)] Sleeps less [TE > non-TE* (TE:22.0%, SY:13.2%, SE:10.4%, TY:0%)] |

n.a. |

| Sok S et al (2009)38 | [Sleep scale A] Score of sleep state [TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE:37.80 ± 0.63, SY:34.93 ± 0.43, SE:32.95 ± 0.33)] |

[Graphic rating scale]|| Satisfaction of Sleep [TE > SY > SE‡ (TE:5.79 ± 0.68, SY:4.13 ± 0.62, SE:3.31 ± 0.75)] |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Questionnaire made by Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine.

Graphic rating scale made by Song et al.55

n.a., not available; N.S., not significant; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SE, So-Eum; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

3.6. Bowel movement and defecation

With regard to the characteristics of defecation, 10 studies were identified (Table 5),20, 23, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 40 and six of them showed specific features of defecation and stool.20, 28, 31, 35, 37, 40 Two studies showed that the Tae-Eum type tends to have partly solid28 or thick31 stool, whereas two other studies reported that the So-Eum type has tender stool20 or constipation.40 One study noted that the So-Yang and So-Eum types have relatively looser stool (as in diarrhea) than the Tae-Yang and Tae-Eum types.35 Another study indicated that the possibility of gold-colored stool decreases in this order: Tae-Eum, So-Eum, and So-Yang.37

Table 5.

Sasang type-specific features in bowel movement and defecation

| References | Condition of stool | Frequency of defecation | Feeling after evacuation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kim K et al (2010)20 | Overall: tender [SE > SY > TE‡ (24.4%, 10.7%, 9.3%)]; 20s: tender [SE > SY > TE‡ (23.4%, 9.8%, 5.0%)]; 60s: N.S. |

N.S. | n.a. |

| Baek YH et al (2010)23 | n.a. | SF-36 [difference between regular and irregular (SY > TE > SE)†] | n.a. |

| Shin SW et al (2013)27 | n.a. | Unable to excrete some days [SE, TE, SY* (24.5%, 16.6%, 9.9%)] | n.a. |

| Choi JY et al (2002)28 | Partly solid [TE > SY > SE† (TE:20.3%, SY:18.4%, SE:9.9%)], thick: N.S. | n.a. | N.S. |

| Kwon JH et al (2013)29 | n.a. | Unable to excrete some days [SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:50.0%, SY:25.0%, TE:25.0%)], no problem with excretion [TE > SY, TE > SE† (TE:41.0%, SY:32.0%, SE:27.0%)] | n.a. |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | Thick [TE > SY > SE† (13.8%, 10.8%, 7.2%)] | n.a. | n.a. |

| Jang ES et al (2007)32 | n.a. | n.a. | Good [TE > SE, SY, > SE* (TE:35.8%, SY:33.1%, SE:22.2%)], moderate [SE > SY > TE* (SE:55.6%, SY:50.8%, TE:36.9%)], discomfort [TE > SY, SE > SY* (27.3%, SE:22.2%, SY:16.1%)] |

| Park HJ et al (2006)35 | Diarrhea in poor condition (SY+SE > TY+TE) | SY+SE < TY+TE | Less discomfort from constipation (SY+SE > TY+TE) |

| Kim YY et al (2012)37 | Golden-colored stool [non-SY > SY† (TE:35.7%, SE:34.9%, SY:15.1%)] | N.S. | Tenesmus [SY > non-SY† (SY:15.1%, SE:6.3%, TE: 0%)] |

| Choi JY, (2004)40 | Constipation (SE > TE, SE > SY) | Less (SE > SY > TE) | n.a. |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

n.a., not available; N.S., not significant; SE, So-Eum; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

Five studies presented significant differences between the Sasang types in terms of bowel movement or the number of defecations a day.23, 27, 29, 35, 40 One study showed that the influence of irregular defecation decreases in this order: So-Yang, Tae-Eum, and So-Eum.23

The frequency of defecation is higher in the So-Yang and So-Eum types than in the Tae-Yang and Tae-Eum types in one study35 and increases in the order of So-Eum, So-Yang, and Tae-Eum type in another.40 Two studies also showed that mainly the So-Eum type is sometimes unable to defecate;27, 29 one of them showed that the Tae-Eum type tends to have no problem with defecation.29

Three studies dealt with the feeling after defecation.32, 35, 37 One study showed that the feeling after defecation is good in the Tae-Eum and So-Yang types but uncomfortable in the Tae-Eum and So-Eum types.32 Another study showed that the So-Yang type has a high tendency toward tenesmus,37 while the third study reported that the So-Yang and So-Eum types do not feel discomfort in constipation.35

3.7. Urination

Six studies had clinical data on urination according to Sasang type (Table 6).20, 26, 31, 32, 35, 40 One article reported that the So-Eum type has the highest frequency of urination, followed by the So-Yang and Tae-Eum types.31 Three articles showed that the Tae-Eum type or both the Tae-Yang and Tae-Eum types have a higher frequency with foamy urine, which can be seen in high blood glucose or diabetes.31, 35, 40

Table 6.

Sasang type-specific clinical features in urination

| References | Frequency of urination | Strength of urination | Symptom of urination | Feeling after urination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim K et al (2010)20 | N.S. | N.S. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Jang ES et al (2009)26 | N.S. | N.S. | SF-36 [difference between no symptom and some symptom (SE > TE, SE > SY)‡] | n.a. |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | SE > SY > TE† (72.2%, 52.5%, 41.3%) | n.a. | Foamy [TE, SY, SE† (12.4%, 6.9%, 6.8%)] | n.a. |

| Jang ES et al (2007)32 | n.a. | n.a. | Yellow [TE > SE > SY* (47.4%, 41.2%, 29.2%)] | Good [SE > TE > SY† (SE:52.5%, TE:47.6%, SY:33.9%)], moderate [SY, TE, SE† (55.1%, 41.4%, 38.6%)], discomfort [TE, SY, SE† (11.0%, 11.0%, 8.9%)] |

| Park HJ et al (2006)35 | N.S. | N.S. | Foamy (TY+TE > SY+SE) | n.a. |

| Choi JY, (2004)40 | n.a. | n.a. | Foamy (TE > SE, SY > SE) | n.a. |

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

n.a., not available; N.S., not significant; SE, So-Eum; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

One study showed that straw-colored urine is frequently shown in decreasing order of the Tae-Eum, So-Eum, and So-Yang types.32 Another showed that changes in the color of urination may be related to the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) measures of So-Yang, Tae-Eum, and So-Eum types (in decreasing order).26 Yet another showed that the So-Eum type tends to have a good feeling after urination, the So-Yang type has a moderate feeling, and the Tae-Eum and So-Yang types feel discomfort.32

3.8. Susceptibility to stress or fatigue

Seventeen studies showed clinical data on susceptibility to stress or fatigue (Table 7).21, 23, 29, 31, 34, 37, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 Two studies reported that the So-Eum type is the most susceptible to general stress,44, 51 whereas another suggested that the Tae-Eum type is.21 Two studies dealt with stress responses, such as depression, anxiety, and emotional irritability.45, 52 The So-Eum type appears to be the most susceptible to stress, but sometimes the So-Yang type is. Three studies showed data on psychosocial stress, saying that the proportion of So-Eum types is higher in high-risk groups with stress than that of other types46, 47 and that of Tae-Eum types is higher in normal-risk groups.45

Table 7.

Sasang type-specific clinical features of susceptibility to stress or fatigue

| References | Stress or fatigue | Degree of susceptibility |

|---|---|---|

| Park GS et al (2003)21 | General stress | Susceptible (TE > SY > SE†) |

| Kim YY et al (2011)34 | Fatigue when waking up | SE > SY, SE > TE† (SE:31.0%, SY:26.3%, TE:25.4%) |

| Baek YH et al (2010)23 | Fatigue degree, fatigue time | SF-36: N.S. |

| Baek YH et al (2009)31 | Fatigue in the morning | SE > non-SE† (SE:30.5%, TE:23.1%, SY:22.1%) |

| Kwon JH et al (2013)29 | Fatigue in the afternoon | SE > non-SE† (SE:50.0%, SY:36.4%, TE:13.6%) |

| Kim YY et al (2012)37 | Fatigue time | N.S. |

| Cho JH et al (2007)43 | Chronic fatigue | SY > SE > TE (SY:41.4%, SE:34.5%, TE:24.1%) |

| Yoo JH et al (2003)44 | General stress | Perception of stress (SE > TE > SY†) |

| Choi EY et al (2008)45 | Stress response | Depression symptom (SE > SY > TE > TY†), anxiety (SE > SY > TY > TE†), emotional irritability (SY > SE > TY > TE*), total stress response (SE > SY > TY > TE†) |

| Cha NH et al (2005)46 | Psychosocial stress, job stress | Psychosocial stress: high-risk group [SE > TE > SY* (SE:27.1%, TE:20.1%, SY:18.0%), moderate-risk group [SY > TE > SE* (SY:78.2%, TE:75.5%, SE:70.7%)]; job stress: N.S. |

| Seo BY et al (2003)47 | Psychosocial stress | Statistical difference: N.S. (p=0.085); optimal scaling and homogeneity analysis: high-risk group (SE > TE, SE > SY), potential-risk group (SY > SE, SY > TE), normal group (TE > SE, TE > SY) |

| Kim K et al (2013)48 | Fatigue | Fatigue severity (SE > SY > TE) |

| Shin EJ et al (2004)49 | Common fatigue degree, distress due to fatigue, degree of daily activity fatigue, fatigue frequency in the previous week | Common fatigue degree (SE > SY > TE†), distress due to fatigue (SE > SY > TE†), degree of daily activity fatigue (N.S.), fatigue frequency in the previous week (N.S.), total degree of fatigue (SE > SY > TE†) |

| Lee AY et al (2013)50 | Postnatal depression, fatigue | N.S. |

| Jeon EY et al (1992)51 | Stress | Stress perceptual level (SE > SY, SE > TE‡) |

| Chang JY et al (2012)52 | Response to stress (e.g., school life, interpersonal, self-problem, environmental, home problem stress) | Depression (SE > TE > SY), emotional irritability / anger (TE > SY > SE), anxiety/fear (SE > SY > TE), cognitive disorganization (SE > SY > TE), habitual patterns (SY≒SE > TE), peripheral vascular syndrome (SE > TE > SY), upper airway syndrome (N.S.), central neurological syndrome (SY > SE > TE), gastrointestinal syndrome (SE≒TE > SY), awakeness syndrome (SE > SY≒TE), muscle tension (SY≒SE > TE) |

| Kim KB et al (2001)53 | Hemodialysis patients’ stress | N.S. |

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

n.a., not available; N.S., not significant; SE, So-Eum; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SY, So-Yang; TE, Tae-Eum; TY, Tae-Yang.

With regard to fatigue, six studies were identified.29, 31, 34, 43, 48, 49 The So-Eum type tends to feel tired in the morning31, 34 and afternoon.29 Also, fatigue severity,48 the common degree of fatigue,49 distress due to fatigue,49 and the total degree of fatigue49 were highest in the So-Eum type. One study reported that the frequency of chronic fatigue decreases in this order: So-Yang, So-Eum, and Tae-Eum.43

4. Discussion

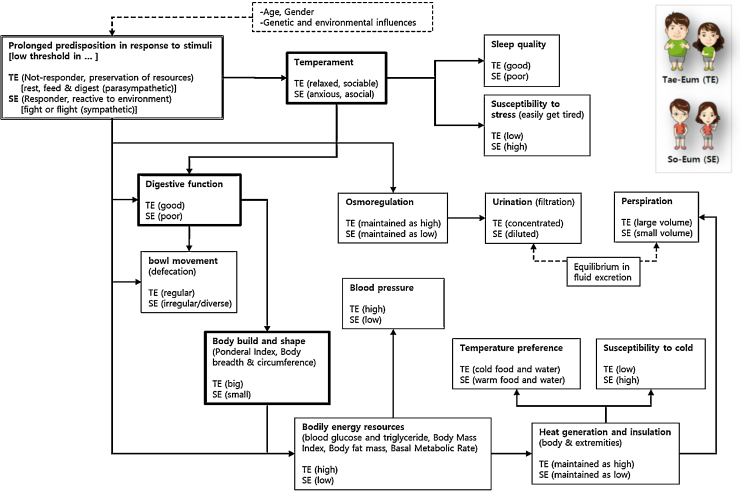

This study systematically reviewed the significant differences between Sasang types in terms of TSPS, including perspiration (Table 2), temperature preference (Table 3), sleep (Table 4), defecation or bowel movement (Table 5), urination (Table 6), susceptibility to psychological stress or fatigue (Table 7), and other biopsychological characteristics, and analyzed them to illuminate the latent physiological mechanisms (Table 8, Fig. 2).

Table 8.

Summary of type-specific pathophysiological symptoms and sympathetic reactivity of each Sasang type

| Sasang type | Digestive function8 | Bowel movement and defecation | Ponderal index,4 body mass index,1, 4, 8 body fat mass1 | Temperature preference | Perspiration (amount and feeling after it) | Urination | Sleep | Susceptibility to stress or fatigue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tae-Yang | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| So-Yang | Moderate or good | Feels good when regular23 | Middle | Moderate24, 27, 29, 31, 32 | Moderate amount20, 22, 24, 27, 31, 32, 41 Moderate feeling24, 31, 41 |

– | – | Moderate29, 34, 46, 47, 48, 52 |

| Tae-Eum | Good | Good condition20, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37 | High | Prefers cold24, 27, 29, 31, 32, 36, 40 | Excessive amount,20, 22, 24, 27, 29, 31, 32, 39, 41 fresh24, 31, 32, 41 |

Foamy31, 35 or yellow32 | Good38 | Low29, 34, 43, 47, 48, 49, 52 |

| So-Eum | Poor | Various conditions20, 27, 29, 35, 40 | Low | Prefers warm24, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 36, 40 | Less amount,20, 22, 24, 27, 31, 32, 39, 40, 41 fatigue22, 24, 31, 32, 40, 41 | Less foamy40 and less frequent,31 feels good after urination32 |

Not good33, 38 | High29, 31, 34, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 52 |

Fig. 2.

Schematic type-specific physiology of Tae-Eum (TE) and So-Eum (SE) Sasang types, which showed opposite clinical characteristics. The bold-outlined boxes are the major biopsychological features of the Sasang typology.

Although previous studies have tried to shape a clinical phenotype by measuring each clinical symptom of each Sasang type, they did not examine the underlying physiological mechanisms by combining all the Sasang type-specific pathophysiological and clinical predispositions.8, 9 Insufficient primary data14 and a lack of an operational definition or standardized objective measure of the clinical features8, 17 of the Sasang typology might be the reason. However, this narrative description of symptoms has an inherent limitation for a generalizable understanding of the complex biological system of the Sasang typology.

In this study, the systematic description of the pathophysiological predispositions of each Sasang type provided clinical phenotypes related to the Sasang typology (Table 8, Fig. 2) and showed significant differences between the Tae-Eum and So-Eum Sasang types, and the So-Yang in between both of them.

The Tae-Eum Sasang type is a person with strong anabolism and energy-saving and weak sympathetic or strong parasympathetic activation.2, 3, 56 The TSPS (Fig. 2) showed that the Tae-Eum type has a good digestive function, good bowel movement and defecation, and a large body build and shape, as previously reported.8, 17 The Tae-Eum type prefers cold food and water and is resistant to cold distress, which might result from the high heat generation36, 54 and insulation associated with the physical characteristics of high basal metabolic rate, blood glucose and triglyceride concentration, body mass index, and body fat mass.4, 57, 58 The Tae-Eum type has a large volume of sweat and feels fresh after sweating, and the urine is highly concentrated as dark yellow to maintain equilibrium in fluid excretion and relatively high osmolality, shown as the type-specific symptom of thirst.37 Tae-Eum types have relatively good sleep quality and low susceptibility to stress from their low state anxiety and sociable nature.5

The Tae-Eum Sasang type seems to have increased parasympathetic reactivity in general and therefore an anabolism dominant state, which easily results in a high body mass index8 and body fat mass1 and overweight59, 60 with cardiovascular61 and metabolic disease.32, 57, 58, 62, 63 Although the blood pressure increase is generally induced by the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, the high blood pressure of Tae-Eum types with low sympathetic activation is brought about by obesity and high blood triglyceride levels and body fat mass.57, 58, 61 Good perspiration represents the healthy state of the Tae-Eum type2 because the generated heat can be drained by it36, 54 and, as a result, straw-colored or dark yellow urine might be attributed to excessive sweating.64 Tae-Eum types might elevate heat generation owing to their increased lean body mass and elevated thyroid metabolic activity compared with others.4

Tae-Eum Sasang type-specific medicinal herbs disperse and eliminate dampness2, 56 and increase the catabolism and sympathetic activity controlling sweating.14, 16 Ephedra sinica, a representative type-specific herb for the Tae-Eum Sasang type, increases the metabolic rate.65, 66 However, it has adverse effects, such as insomnia and tachycardia,1, 67 with the So-Eum Sasang type.1, 2, 3

The TSPS of the So-Eum Sasang type is the opposite of those of the Tae-Eum Sasang type. The So-Eum Sasang type has weak intake and poor digestive function and bowel movement.2, 3, 56 As a result, the So-Eum type has a small build and shape with a low ponderal index, small neck and chest circumferences, and consequently, low blood glucose and triglyceride levels, body mass index, basal metabolic rate, and body fat mass.4, 8, 57, 58 As for temperature preference, the So-Eum type prefers warm or hot food and water and is not resistant to cold distress. So-Eum types have relatively poor sleep quality and is easily disturbed because of their high state anxiety,5 which might be the result of prolonged elevated sympathetic activation.

The type-specific clinical symptoms of the So-Eum Sasang type in urination, digestive function, bowel movement, and defecation might be related to the activated sympathetic nervous system, which stimulates the contraction of sphincters and suppresses the tension and contraction of the wall of the digestive tract and urinary bladder, resulting in the clinical symptoms of poor bowel movement and urination. They might also be related to the suppressed parasympathetic nervous system, which maintains the peristaltic rhythm of the intestines as well as decent digestive function.

So-Eum Sasang types have poor spleen function2 and frequent digestion-related problems, unstable bowel movement, and dyspepsia8 owing to their high sympathetic reactivity and stress responses, which might be the reason for their low body mass index and small body build.8, 17 The low basal metabolic rate, body fat mass, and body mass index4 might explain their vulnerability to cold distress and their small volume of sweat.

As a whole, these clinical phenotypes of the Tae-Eum and So-Eum Sasang types might be explained with autonomic reactivity, an individual autonomic response in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (Fig. 2). Each Sasang type might have his or her typical predisposition to maintaining homeostasis or a slightly high or low set-point with sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity.15, 16 The autonomic nervous system regulates and maintains the homeostasis of basic functions of the human body.14, 15, 16 The sympathetic nervous system is activated to prepare for fight or flight from a potential threat, and the parasympathetic nervous system promotes relaxation and facilitates eating and digestion to preserve resources, controlling bodily myogenic tonus, perspiration, waste discharge, secretion and movement in the digestive system, the volume and tonicity of bodily fluids, blood pressure, and body temperature as well as psychological activity.

Although here we showed that the type-specific clinical features of the Sasang typology might be explained by autonomic reactivity, there are significant differences from the sympathicotonia–vagotonia and autonomic liability theories of Western biomedicine, which are too one-sided to be useful and cannot be objectively assessed.68 Sympathicotonia–vagotonia relates certain diseases with the autonomic nervous system based primarily on the blood pressure and heart rate,69, 70 and autonomic liability refers to the arousability or easy activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in response to a stress as a biological basis of neuroticism.71, 72, 73 However, the Sasang typology provides proven clinical prototypes using acupuncture and medicinal herbs based on type-specific biopsychological and clinical features, and has the clinical heritage of Korean medicine and the theoretical backbone of yin–yang philosophy and Confucianism.3

Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain the psychological, physical, and clinical prototypes of the Sasang typology. The temperament hypothesis indicates that novelty seeking and harm avoidance, from the biopsychosocial personality theory of Cloninger, can explain the psychobiological characteristics of the So-Yang and So-Eum Sasang types.11, 13 The hypothalamus hypothesis shows that the Tae-Eum and So-Eum Sasang types have poorly and highly activated hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axes, respectively—that is, they are nonresponders and responders to environmental stimuli.4

Here we showed the autonomic reactivity hypothesis—based on the TSPS of digestive function, bowel movement and defecation, urination, perspiration, sleep, temperature preference, body build, temperament, and sensitivity to stress—that sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity might be under the influence of the hypothalamus, which controls fundamental responses to environments and maintains inner homeostasis for survival4 as a part of the limbic system (which governs basic emotion, motivation, desire, and learning).

Although this study aimed to review previous clinical reports to elucidate the physiological mechanisms related to TSPS, there are still limitations on the generalization of our findings. First, many of the articles in this review were descriptions of fragmented clinical symptoms without standardized or structured measures, and these are indirect evidence for confirmation. More clinical and animal studies are needed for constructing equations to re-evaluate and explain the physiological model of the TSPS of each Sasang type.

Second, we need adequate explanations for each Sasang TSPS for the autonomic reactivity hypothesis. There should be more studies on the control of body fluids and electrolyte balance in terms of osmoregulation for urination, perspiration, and thirst37, 74 and body fat mass, thermoregulation, the vasomotor system, and heat production and outflow for temperature preference to clarify the latent mechanisms.

Third, we could not make any decisive speculations on the Tae-Yang Sasang type because of the insufficiency of clinical reports. Considering that the health of the Tae-Yang Sasang type correlates with the increase of urination volume, which can be described as lowered sympathetic activity,2 the Tae-Yang Sasang type, which has a persistent, asocial, and extroverted temperament and small body shape,3 might have increased sympathetic reactivity compared with others.

Although there are limitations on generalization, the findings provide suggestions for future studies. First, the characteristics of each Sasang type can be explained as predisposition to one side or having a slightly high or low set-point,74 which can be likened to a seesaw.2, 56 Given this, the physiological mechanism of the Sasang typology could be understood through systems medicine, as suggested by reviews on the genetic features of the Sasang typology,9, 10 not the knockout or modification of several genes related to specific functions.

Second, as for the validation of the autonomic reactivity and hypothalamus hypotheses, we need clinical studies on patients with hypothalamus-related diseases, such as the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, body temperature, and body fluid circulation.

Third, we need to carefully examine the type-specific clinical features and split them into physiological predisposition and pathological symptoms with respect to sympathetic and parasympathetic reactivity, the HPA axis, the hypothalamus, and the limbic system for a better understanding of the Sasang typology.

Fourth, the physiological responses to Sasang type-specific medicinal herbs and acupuncture3 in the HPA axis and autonomic responses should be tested in animals and humans. Previous studies have listed Sasang type-specific medical herbs, such as Ephedrae Herba, Liriopis Tuber, Schisandrae Fructus, Dioscoreae Rhizoma, Platycodi Radix, Coicis Semen, and Puerariae Radix for the Tae-Eum type and Ginseng Radix, Atractylodis Rhizoma White, Glycyrrhizae Radix, Cinnamomi Cortex, Citri Pericarpium, and Zingiberis Rhizoma Crudus for the So-Eum type.3, 12

In this systematic review, we thoroughly collected Sasang type-specific clinical features and analyzed them to elucidate the underlying physiological mechanisms as an autonomic reactivity hypothesis. With further studies supporting this hypothesis, we might re-interpret each Sasang type as a typical psychobiosocial type for better understanding of the Sasang typology and integrative medicine combining Western biomedicine and traditional Korean personalized medicine.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Chae H., Lyoo I.K., Lee S.J., Cho S., Bae H., Hong M. An alternative way to individualized medicine: psychological and physical traits of Sasang typology. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:519–528. doi: 10.1089/107555303322284811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J. Lee JM; Seoul: 1894. Dong-yi-soo-se-bo-won (Longevity and life preservation in Eastern medicine) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S.J., Park S.H., Cloninger C.R., Kim Y.H., Hwang M., Chae H. Biopsychological traits of Sasang typology based on Sasang personality questionnaire and body mass index. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:315–325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chae H., Kown Y.K. Best-fit index for describing physical perspectives in Sasang typology. Integr Med Res. 2015;4:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae H., Park S.H., Lee S.J., Kim M.G., Wedding D., Kwon Y.K. Psychological profile of Sasang typology: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):21–29. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S.J., Park S.H., Chae H. Study on the temperament construct of Sasang typology with biopsychological measures. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2013;27:261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae H., Lee S., Park S.H., Jang E., Lee S.J. Development and validation of a personality assessment instrument for traditional Korean medicine: Sasang personality questionnaire. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2012;2012:657013. doi: 10.1155/2012/657013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee M.S., Sohn K., Kim Y.H., Hwang M.-W., Kwon Y.K., Bae N.Y. Digestive system-related pathophysiological symptoms of Sasang typology: systematic review. Integr Med Res. 2013;2:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn K., Jeong A., Yoon M., Lee S. Genetic characteristics of Sasang typology: a systematic review. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2012;5:271–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim B.Y., Yu S.G., Kim J.Y., Song K.H. Pathways involved in Sasang constitution from genome-wide analysis in a Korean population. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:1070–1080. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S.J., Cloninger C.R., Cloninger K.M., Chae H. The temperament and character inventory for integrative medicine. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2014;25:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S.H., Kim M.G., Lee S.J., Kim J.Y., Chae H. Temperament and character profiles of Sasang typology in an adult clinical sample. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2011;2011:794795. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S.J., Kim S.H., Lim N., Ahn M.Y., Chae H. Study on the difference of BIS/BAS scale between Sasang types. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:805819. doi: 10.1155/2015/805819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K.A., Park S.S., Lee W.C. A study on sweat, defecation, and urination of Sasang constitutional medicine. J Korean Orient Intern Med. 1996;17:123–138. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J.H., Seo E.H., Ha J.H., Choi A.R., Woo C.H., Goo D.M. A study on the Sasang constitutional differences in heart rate variability. J Sasang Const Med. 2007;19:176–187. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwak C.K., Sohn E.H., Lee E.J., Koh B.H., Song I.B., Hwang W. A study about Sasang constitutional difference on autonomous function after acupuncture stimulation. J Sasang Const Med. 2004;16:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M., Bae N.Y., Hwang M., Chae H. Development and validation of the digestive function assessment instrument for traditional Korean medicine: Sasang digestive function inventory. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:263752. doi: 10.1155/2013/263752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S.W., Jang E.S., Lee J., Kim J.Y. Current researches on the methods of diagnosing Sasang constitution: an overview. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):43–49. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang E.S., Kim M.G., Baek Y.W., Kim Y.J., Kim J.Y. Influence of cold and heat characteristics and health state in Sasang constitution diagnosis. J Sasang Const Med. 2009;21:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K., Oh S.Y., Joo J.C., Jang E.S., Lee S.W. Comparison of digestion, feces, sweat and urination according to Sasang constitution in the 20s and 60s. J Sasang Const Med. 2010;22:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park G.S., Kim H.K. A study on eating habits by body constitution types of the Sasang constitutional medicine among female college students. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2003;32:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi J.Y., Lee Y. The characteristics of perspiration according to Sasang constitution. J Korean Orient Med. 2002;23:186–195. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baek Y., Yoo J., Kim H., Jang E. The association between symptom evaluation index and quality of life according to Sasang constitution in men. J Sasang Const Med. 2010;22:48–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H.J., Lee H.J., Jin H.J., Kim M.G. Analysis of Sasang constitutional deviation of health condition according to the tendency of perspiration. J Sasang Const Med. 2009;21:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim T.Y. Department of Physical Education, Sookmyung Women's University; Seoul: 2014. Difference of the physical fitness and obesity according to the quality of sleep and Sasang constitution. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang E., Yoo J.H., Baek Y.W., Kim H.S., Kim J.Y., Lee S.W. The association between symptom evaluation index and health state according to Sasang constitution in women. J Sasang Const Med. 2009;21:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin S.W., Lee J. Study on the characteristics of ordinary symptoms in overweight and obesity patients according to Sasang constitution. J Soc Korean Med Obes Res. 2013;13:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S., Choi J. A clinical study of stool according to Sasang constitution. J Sasang Const Med. 2002;14:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon J.-H., Park H.-J., Pham D.D., Dong S.-O., Jang E.-S., Lee S.-W. A study on the physiological symptoms and pathological symptoms of Vietnamese according to Sasang constitutions. J Sasang Const Med. 2013;25:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S.H., Han S.S., Jang E.S., Kim J.Y. Clinical study on the characteristics of heat and cold according to Sasang constitutions. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2005;19:811–814. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baek Y.H., Kim H.S., Lee S.W., Ryu J.H., Kim Y.Y., Jang E.S. Study on the ordinary symptoms characteristics of gender difference according to Sasang constitution. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2009;23:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jang E.S., Kim H.S., Lee H.J., Baek Y.H., Lee S.W. The clinical study on the ordinary and pathological symptoms according to Sasang constitution. J Sasang Const Med. 2007;19:144–155. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S.S., Choi J.R. A clinical study of sleep according to Sasang constitution. J Sasang Const Med. 2003;15:204–215. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y.Y., Kim H.S., Baek Y.H., Yoo J.H., Kim S.H., Jang E.S. A study on the constitution type-specific presentation of physical symptoms. J Sasang Const Med. 2011;23:340–350. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park H.J., Lee Y.S., Park S.S. A comparative study on the characteristics (sweat, stool, urine, digestion) of soyang.soeumin and taeyang.taeumin in Sasang constitution. J Sasang Const Med. 2006;18:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S.H., Lee E.S., Kim J.E., Park K.M., Lee J.Y., Choi H.S. An experimental study on individual difference in reaction to mild environment in adult males—on the perspective of Sasang constitution. J Korean Orient Med. 2005;26:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y., Yoo J., Kim H., Lee S. A study on the physiological symptoms and pathological symptoms of Japanese to Sasang constitution. J Sasang Const Med. 2012;24:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sok S., Kim K.B. A comparative study on sleep state, satisfaction of sleep, and life satisfaction of Korean elderly living with family by Sasangin constitution. J Korean Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs Acad Soc. 2009;18:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S.K., Ko B.H. An analysis on the charateristics of Sasang constitution—centering on the body measures and diagnosis results. J Sasang Const Med. 1996;8:349–376. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi J.Y. Department of Oriental Medicine, Dongguk University; Seoul: 2004. A study of ordinary symptoms according to Sasang constitution using logistic regression. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung S.O., Park S.J., Chae H., Park S.H., Hwang M., Kim S.H. Analysis of skin humidity variation between Sasang types. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6(Suppl 1):87–92. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y.M., Ku B., Jung C.J., Kim J.U., Jeon Y.J., Kim K.H. Constitution-specific features of perspiration and skin visco-elasticity in SCM. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho J.H., Yoo S., Cho J., Son C.G. Analytic study for syndrome-differentiation and Sasang-constitution in 72 adults with chronic fatigue. J Korean Orient Intern Med. 2007;28:791–796. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoo J.H., Lee H.Y., Lee E.J. Perception and ways of coping with stress of Sasangin. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2003;15:173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi E.Y., Chang B.S. A study on the differences of stress responses according to Sasang constitutions. Korean J Orient Prev Med Soc. 2008;12:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cha N.H., Wang M.J., Kim J.A., Lee K.N. Difference of physical symptoms, PWI and JCQ according to Sasang constitutions for industrial workers. J Korean Community Nurs. 2005;16:508–516. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seo B.Y., Kwon S.H., Kim S.T., Seo J.Y., Jung H.K., Kim Y.C. The study on stress evaluation with Sasang constitution and lifestyle for labors in workplace. Korean J Orient Prev Med Soc. 2003;7:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim K., Ha Y.J., Park S.J., Choi N.R., Lee Y.S., Joo J.C. Characteristics of fatigue in Sasang constitution by analyzing questionnaire and medical devices data. J Sasang Const Med. 2013;25:306–319. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shin E.J., Han S.H. The degree of fatigue depending on constitution in middle-aged women. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2004;10:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee A.Y., Park G.Y., Lee E.H. Changes of depression and fatigue level according to Sasang constitution in early postpartum women. J Orient Obstet Gynecol. 2013;26:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pham D.D., Lee J.H., Park E.S., Baek H.S., Kim G.Y., Lee Y.B. A research on health state according to stress perceptual level by constitution of the Korean. J Korean Acad Nurs. 1992;22:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang J.Y., Kim K.S., Kim B.S. Study of on academic stress responses according to Sasang constitutions of oriental medicine college students. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2012;23:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim K.B., Park S.O. A study of the correlation of stress and powerlessness based on hemodialysis patients’ constitution of the Korea. J East-West Nurs Res. 2001;6:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pham D.D., Lee J.H., Park E.S. Thermoregulatory responses to graded exercise differ among Sasang types. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:879272. doi: 10.1155/2015/879272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song M., Kim S., Oh J.J. Sleep change of older adults and nursing research. J Korean Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs Acad Soc. 1995;4:45–64. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J.Y., Pham D.D. Sasang constitutional medicine as a holistic tailored medicine. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6:11–19. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi K., Lee J., Yoo J., Lee E., Koh B., Lee J. Sasang constitutional types can act as a risk factor for insulin resistance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:e57–e60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee T.G., Koh B., Lee S. Sasang constitution as a risk factor for diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2009;6:99–103. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee Y.O., Kim J.W. A clinical study of the type of disease and symptom according to Sasang constitution classification. J Sasang Const Med. 2002;14:74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee T.G., Lee S.K., Choi B.K., Song I.B. A study on the prevalences of chronic diseases according to Sasang constitution at a health examination center. J Sasang Const Med. 2005;17:32–45. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scherrer U., Randin D., Tappy L., Vollenweider P., Jequier E., Nicod P. Body fat and sympathetic nerve activity in healthy subjects. Circulation. 1994;89:2634–2640. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olive J.L., Ballard K.D., Miller J.J., Milliner B.A. Metabolic rate and vascular function are reduced in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metab Clin Exp. 2008;57:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buscemi S., Verga S., Caimi G., Cerasola G. A low resting metabolic rate is associated with metabolic syndrome. Clin Nutr. 2007;26:806–809. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vander A.J., Sherman J.H., Luciano D.S. WCB McGraw-Hill; Boston: 2001. Human physiology. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boozer C.N., Nasser J.A., Heymsfield S.B., Wang V., Chen G., Solomon J.L. An herbal supplement containing ma huang-guarana for weight loss: a randomized, double-blind trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:316–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801539. Boston. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boozer C.N., Daly P.A., Homel P., Solomon J.L., Blanchard D., Blanchard J.A. Herbal ephedra/caffeine for weight loss: a 6-month randomized safety and efficacy trial. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:593–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsing L.-c., Yang C.-s., Lee T.-h., Kim L.-h., Kwak M.-j., Seo E.-s. Short-term effects of mahuang on state-trait anxiety according to Sasang constitution classification: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Korean Orient Intern Med. 2007;28:106–114. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Myrtek M. Elsevier; Freiburg: 2012. Constitutional psychophysiology: research in review. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eppinger H., Hess L. Hirschwald; Berlin: 1910. Die vagotonie: eine klinische studie. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Curtius F. Springer; Berlin: 1954. Klinische konstitutionslehre. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eysenck H.J. Transaction Publishers; 1967. The biological basis of personality. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hinton J.W., Craske B. Differential effects on test stress on the heart rates of extraverts and introverts. Biol Psychol. 1977;5:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(77)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stelmack R.M. Biological bases of extraversion: psychophysiological evidence. J Pers. 1990;58:293–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bourque C.W. Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nrn2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]