Abstract

Background

Yijin-tang (YJ) has been used traditionally for the treatment of cardiovascular conditions, nausea, vomiting, gastroduodenal ulcers, and chronic gastritis. In this study, a simple and sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method was developed for the quantitation of nine bioactive compounds in YJ: homogentisic acid, liquiritin, naringin, hesperidin, neohesperidin, liquiritigenin, glycyrrhizin, 6-gingerol, and pachymic acid.

Methods

Chromatographic separation of the analytes was achieved on an RS Tech C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm) using a mobile phase composed of water containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and acetonitrile with a gradient elution at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

Results

Calibration curves for all analytes showed good linearity (R2 ≥ 0.9995). Lower limits of detection and lower limits of quantification were in the ranges of 0.03–0.17 μg/mL and 0.09–0.43 μg/mL, respectively. Relative standard deviations (RSDs; %) for intra- and interday assays were < 3%. The recovery of components ranged from 98.09% to 103.78%, with RSDs (%) values ranging from 0.10% to 2.59%.

Conclusion

This validated HPLC method was applied to qualitative and quantitative analyses of nine bioactive compounds in YJ and fermented YJ, and may be a useful tool for the quality control of YJ.

Keywords: HPLC-DAD, LC/MS, simultaneous determination, validation, Yijin-tang

1. Introduction

Yijin-tang (YJ, Erchen-tang in Chinese, Nichin-to in Japanese) is a traditional prescription for the prevention and treatment of diverse diseases; it has been used widely to treat nausea, vomiting, gastroduodenal ulcers, and chronic gastritis.1 YJ has also been shown to improve digestive function in clinical research trials. Recently, YJ was reported to show therapeutic effects on diseases of the circulatory system and protective effects against gastric mucosa in in vivo experiments.2, 3 YJ is composed of Pinellia ternata Breitenbach, Citrus unshiu Markovich, Poria cocos Wolf, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, and Zingiber officinale Roscoe, according to the Korean Herbal Pharmacopeia. The major components of each herbal medicine in YJ are known to be bioactive components, including flavonoids (e.g., liquiritin, liquiritigenin, hesperidin, rutin, naringin, neohesperidin, and poncirin), triterpenoids (e.g., glycyrrhizin, pachymic acid, and eburicoic acid), phenolic acids (e.g., homogentisic acid), and pungent principles (e.g., 6-gingerol and 6-shogaol).4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 These compounds, derived from each herbal medicine, have various pharmacological activities including anticancer, -inflammatory, -bacterial, and -oxidant activities.4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 In this study, specific biomarkers were selected to evaluate the quality of YJ and its ingredients, including homogentisic acid for P. ternata Breitenbach, hesperidin, naringin and neohesperidin for C. unshiu Markovich, pachymic acid for P. cocos Wolf, liquiritigenin and glycyrrhizin for G. uralensis Fisch, and 6-gigerol for Z. officinale Roscoe (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition and biomarkers of five herbal medicines in Yijin-tang

| Herbal medicine | Amount (g) | Ratio | Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinellia ternata Breitenbach | 800 | 41.0 | Homogentisic acid |

| Citrus unshiu Markovich | 400 | 20.5 | Hesperidin, naringin, neohesperidin |

| Poria cocos Wolf | 400 | 20.5 | Pachymic acid |

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch | 200 | 10.3 | Liquiritigenin, glycyrrhizin |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | 150 | 7.7 | 6-Gingerol |

Several analytical methods for these compounds have been developed for qualitative and quantitative analyses using high-performance liquid chromatography-diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD) and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS).17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 However, these methods cannot simultaneously determine the multiple bioactive components in YJ. Although a HPLC-DAD method to detect six compounds in YJ was recently developed, the identification and quantification of compounds based on retention times and UV spectra are limited due to the interference of nontarget molecular components in YJ.26 Therefore, methods for simultaneously detecting these biomarkers in YJ is needed to ensure efficient quality control and pharmaceutical evaluation using LC/MS.

In this study, a rapid, simple, and efficient analytical method for nine biomarkers in YJ was developed using HPLC-DAD for quantitation and LC/MS for identification. Subsequently, the method was applied to chemically profile targeted analytes in YJ and Lactobacillus-fermented YJ.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

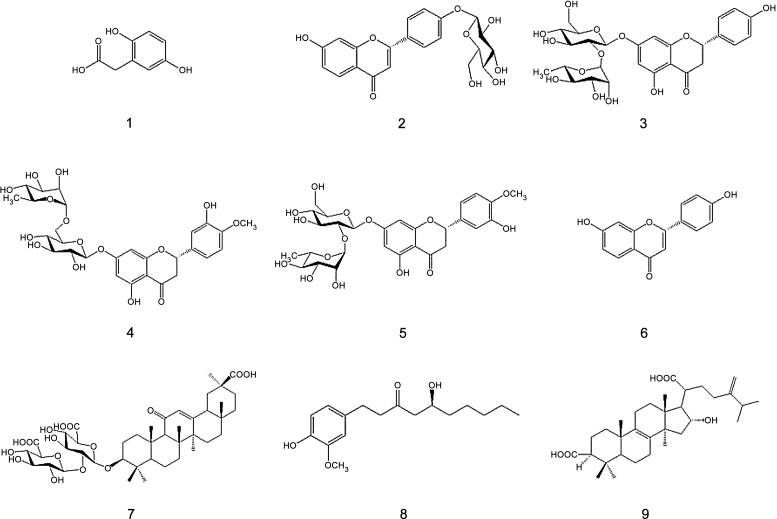

Homogentisic acid, liquiritin, naringin, neohesperidin, and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA.). Liquiritigenin, 6-gingerol, and pachymic acid were obtained from Faces Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Hesperidin and glycyrrhizin were purchased from ICN Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA, USA) and Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. The purity of all standards was > 97%. All herbal medicines were purchased at the Yeongcheon traditional herbal market (Yeongcheon, South Korea). The chemical structures of the nine bioactive compounds are shown in Fig. 1. HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from J.T. Baker Inc. (Philipsburg, NJ, USA). Deionized water was prepared using an ultrapure water production apparatus (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of the nine compounds (1, homogentisic acid; 2, liquiritin; 3, naringin; 4, hesperidin; 5, neohesperidin; 6, liquiritigenin; 7, glycyrrhizin; 8, 6-gingerol, and 9, pachymic acid).

2.2. Preparation and fermentation of YJ

All herb samples were purchased from the Yeongcheon Herbal Store (Yeongcheon, South Korea) and all specimens (#50 for P. ternata Breitenbach, #22 for C. unshiu Markovich, #61 for P. cocos Wolf, #3 for G. uralensis Fisch, and #6 for Z. officinale Roscoe) were stored in the herbarium of the KM Application Center, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine. Five medicinal herbs (1.95 kg, Table 1) were extracted in 19.5 L of distilled water for 3 hours using a COSMOS-660 extractor (Kyungseo Machine Co., Incheon, Korea). Extracts were sieved (106 μm) to yield 15.8 L of the decoction. To ferment YJ, 10 bacterial strains (including Lactobacillus rhamnosus KFRI 144, Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI 150, Lactobacillus amylophilus KFRI 161, L. acidophilus KFRI 162, Lactobacillus plantarum KFRI 166, L. acidophilus KFRI 217, Lactobacillus brevis KFRI 221, L. brevis KFRI 227, Lactobacillus curvatus KFRI 231, and L. acidophilus KFRI 341) were obtained from the Korean Food Research Institute (Seongnam, Korea). Bacterial strains were cultured in de Man, Rogsa and Sharpe (MRS) broth at 37 °C for 24 hours and viable cell counts of each strain were determined in triplicate using a pour plate method on MRS agar. Solutions of YJ extracts were adjusted to pH 8 using 1 M sodium hydroxide and autoclaved for 15 minutes at 121 °C. Sterilized-YJ solutions (500 mL) were inoculated with 5 mL of the inoculum (1% v/v, 2 × 109 CFU/mL). Inoculated samples were incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours and a brownish powder of fermented YJ extract was obtained via lyophilization. These fermented YJ (f-YJ) samples were stored at 4 °C before use.

2.3. Preparation of calibration standards, quality control, and analytical samples

Standard stock solutions of the nine bioactive standards—homogentisic acid, liquiritin, naringin, hesperidin, neohesperidin, liquiritigenin, glycyrrhizin, 6-gingerol, and pachymic acid—were prepared at concentrations of 200 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, 800 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, 600 μg/mL, 200 μg/mL, and 400 μg/mL, respectively, by dissolving them in methanol. The nine bioactive standards were mixed from stock solutions and then diluted serially to five concentrations for the construction of calibration curves. Quality control samples for method validation were prepared at three serially diluted concentrations. The standard stock solutions, calibration standards, and quality control samples were stored at 4 °C before use. The YJ powder and f-YJ (1.0 g) were weighed exactly and dissolved at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in 50% methanol. After dissolution, the samples were centrifuged (8,000 g, 10 minutes, 25 °C) and the suspension was then filtered through a 0.2 μm membrane filter (Whatman International ltd., Maidstone, UK) prior to injection. All working solutions and sample solutions were stored at 4 °C before use.

2.4. Chromatographic conditions

The simultaneous determination of nine bioactive compounds in YJ was conducted using an Elite Lachrom HPLC-DAD system equipped with an L-2130 pump, an L-2200 autosampler, an L-2350 column oven, and an L-2455 photodiode array UV/VIS detector (Lachrom Elite, Hitachi High Technologies Co., Tokyo, Japan). The output signal of the detector was recorded using the EZchrom Elite software (version 3.3.1a, Hitachi High Technologies Co.,Tokyo, Japan). The separation was achieved on a C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm I.D., 5 μm, RS Tech, Daejeon, South Korea) and the column temperature was kept at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% TFA (v/v) water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution system, to improve the chromatographic separation capacity, was programmed as follows: 10% B (0–5 minutes), 10–20% B (5–15 minutes), 20–27% B (15–20 minutes), 27–37% B (20–35 minutes), 37–53% B (35–50 minutes), 53–100% B (50–55 minutes), and 100% B (55–70 minutes) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The detection wavelengths for analytes were set at 254 nm and 280 nm and the injection volume of each sample was 10 μL.

LC/MS analysis of YJ was performed according to a method developed previously with some modification. All LC/MS spectra for qualitative analysis of nine bioactive compounds were acquired using an Agilent 1100 series LC/MS system (Agilent 1100+ G1958, agilent technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed on a Kinetex C18 (100 mm × 4.6 mm inner diameter (I.D.), 2.6 μm, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) by gradient elution, which consisted of 0.1% TFA (v/v) water (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution system was programmed as follows: 10% B (0–5 minutes), 10–20% B (5–15 minutes), 20–27% B (15–20 minutes), 27–37% B (20–35 minutes), 37–53% B (35–40 minutes), 53–100% B (40–45 minutes), and 100% B (45–60 minutes) at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The conditions of the mass spectrometer analysis were optimized and were as follows: ionization source was Atmospheric pressure ionization-electrospray (positive ion mode), scan mode from m/z 100–900, fragmentor voltage was set to 60 V, quadrupole was heated to 99 °C, capillary voltage was set to 3,000 V, nebulizer pressure was set at 35 psig, drying gas flow was 12.0 L/min, drying gas temperature was 350 °C, and the column oven temperature was 40 °C.

2.5. Method validation

The method was validated for selectivity, linearity, precision, accuracy, and recovery. Method validation was carried out according to the Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology Q2 (R1) Guideline of the International Conference on Harmonisation.27

2.5.1. Linearity, limits of detection, and limits of quantification

Standard stock solutions of the nine bioactive compounds were diluted with methanol to appropriate concentrations for plotting the calibration curves. Six different concentrations of the nine bioactive compounds solution were analyzed in triplicate. To demonstrate the linearity of the analytical method, calibration curves were constructed by plotting the concentration of each analyte versus the value of the peak. Lower limit of detection (LLOD) and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for each analyte were determined on the basis of S/N of 3.3 and 10, respectively.

2.5.2. Precision, accuracy, and recovery

The precision of the method was evaluated by intra- and interday tests. Standard solutions at three different concentrations were analyzed. The intraday precision test was performed by analyzing a mixed standard solution in five replicates during 1 day. The interday precision test was conducted by analyzing the same standard solution in five replicates each day on 3 consecutive days. Precision was expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD, %); a value of RSD within 3% is generally acceptable.

A recovery test was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of the method. The recoveries of analytes were determined by adding three different concentrations of each standard solution into the YJ sample solution (5.0 mg/mL) in triplicate. Recovery (%) was calculated with the following equation:

| (1) |

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of chromatographic conditions

Optimized HPLC-DAD and LC/MS conditions were determined as follows. Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analyses of nine bioactive compounds in YJ were carried out using HPLC-DAD and LC/MS (electrospray ionization MS ion trap in positive mode). To improve the chromatographic separation capacity, 0.1% TFA (v/v) water and acetonitrile were used as mobile phases with a gradient elution system. TFA was added to the water to improve the ionization reaction and to reduce peak tailing; as a result, the addition of TFA enhanced the separation capacity and sensitivity.28 Additionally, acetonitrile was found to have a better analyte resolution than MeOH.

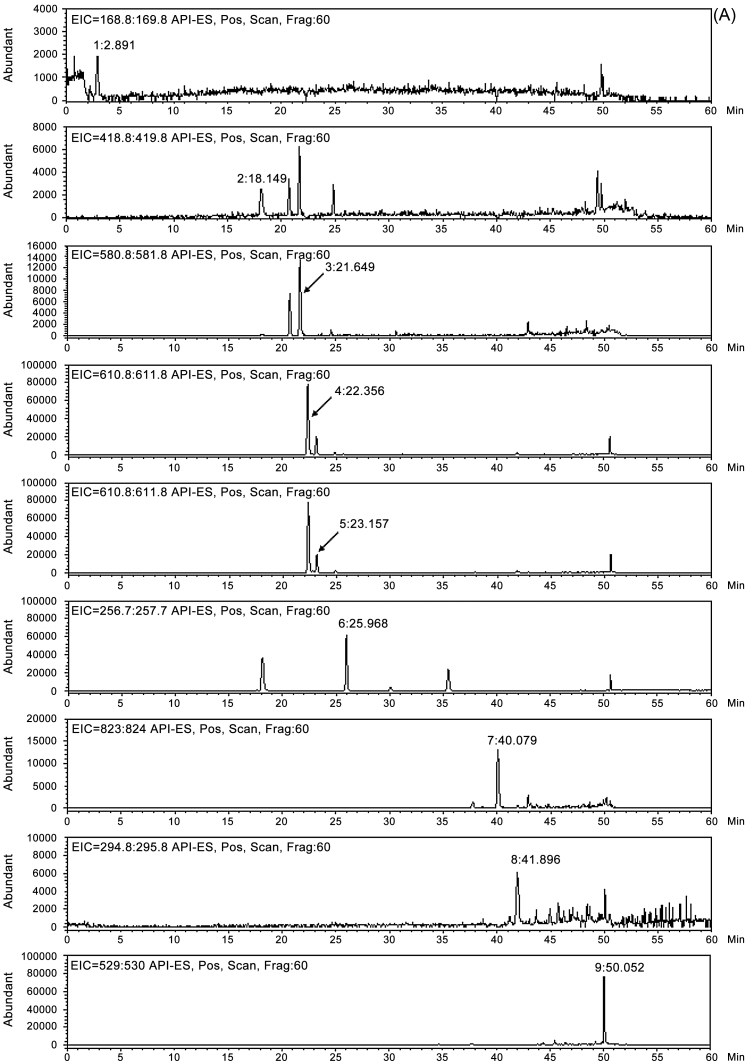

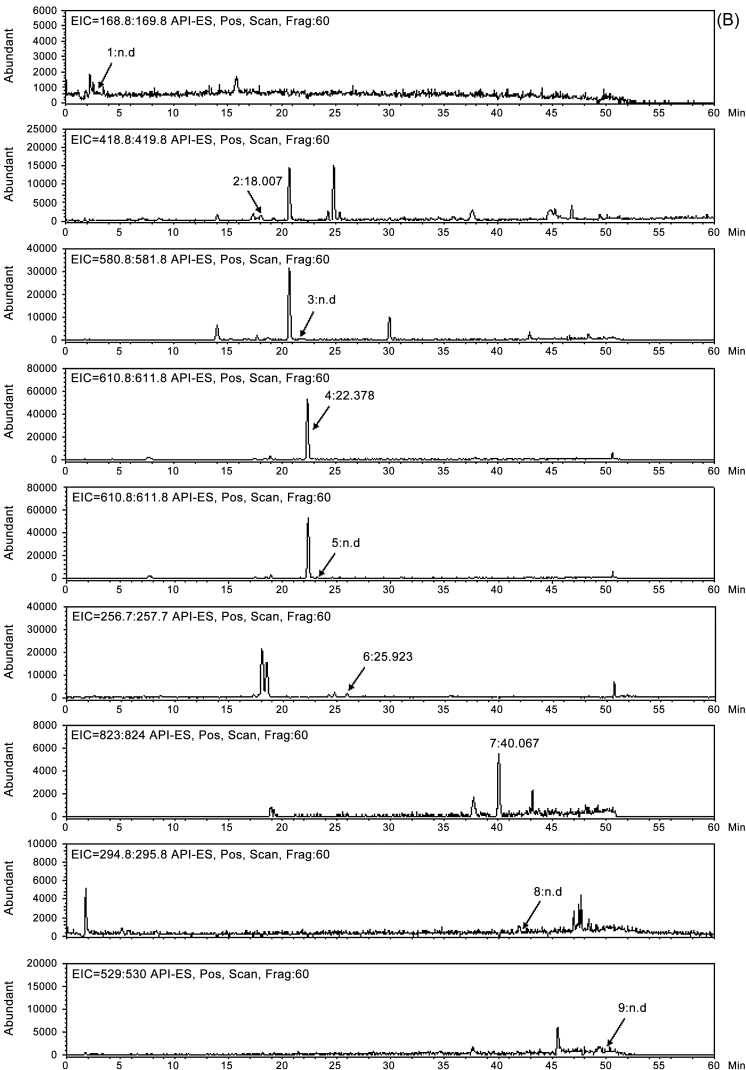

Identification of nine bioactive compounds in YJ was conducted with an LC/MS analysis. An extracted ion chromatogram of the identified compounds is shown in Fig. 2. In positive ion mode, molecular ions for each analyte in the standard mixture were observed at m/z 169.1 [M+H]+ for homogentisic acid, at m/z 419.0 [M+H]+ for liquiritin, at m/z 581.1 [M+H]+ for naringin, at m/z 611.1 [M+H]+ for hesperidin, at m/z 611.1 [M+H]+ for neohesperidin, at m/z 257.0 [M+H]+ for liquiritigenin, at m/z 823.3 [M+H]+ for glycyrrhizin, at m/z 295.1 [M+H]+ for 6-gingerol, and at m/z 529.3 [M+H]+ for pachymic acid. Under the same conditions, molecular ions for each analyte in the YJ control sample were detected at m/z 169.0 [M+H]+ for homogentisic acid, at m/z 419.1 [M+H]+ for liquiritin, at m/z 611.1 [M+H]+ for hesperidin, at m/z 257.0 [M+H]+ for liquiritigenin, and at m/z 823.2 [M+H]+ for glycyrrhizin (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) of the nine components (1, homogentisic acid; 2, liquiritin; 3, naringin; 4, hesperidin; 5, neohesperidin; 6, liquiritigenin; 7, glycyrrhizin; 8, 6-gingerol, and 9, pachymic acid) in the standard mixture. (B) EIC of the nine components (1, homogentisic acid; 2, liquiritin; 3, naringin; 4, hesperidin; 5, neohesperidin; 6, liquiritigenin; 7, glycyrrhizin; 8, 6-gingerol, and 9, pachymic acid) in the Yijin-tang (YJ) sample.

Table 2.

Mass spectral data of the nine analytes

| Peak | Identification | Chemical formula | Calculated mass | Precursor ion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard mixture | ||||

| 1 | Homogentisic acid | C8H8O4 | 168.0 | 169.1 [M+H]+ |

| 2 | Liquiritin | C21H22O9 | 418.1 | 419.0 [M+H]+ |

| 3 | Naringin | C27H32O14 | 580.2 | 581.1 [M+H]+ |

| 4 | Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | 610.2 | 611.1 [M+H]+ |

| 5 | Neohesperidin | C28H34O15 | 610.2 | 611.1 [M+H]+ |

| 6 | Liquiritigenin | C15H12O4 | 256.1 | 257.0 [M+H]+ |

| 7 | Glycyrrhizin | C42H62O16 | 822.4 | 823.3 [M+H]+ |

| 8 | 6-Gingerol | C17H26O4 | 294.2 | 295.1 [M+H]+ |

| 9 | Pachymic acid | C33H52O5 | 528.4 | 529.3 [M+H]+ |

| Yijin-tang sample | ||||

| 1 | Homogentisic acid | C8H8O4 | 168.0 | 169.0 [M+H]+ |

| 2 | Liquiritin | C21H22O9 | 418.1 | 419.1 [M+H]+ |

| 4 | Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | 610.2 | 611.1 [M+H]+ |

| 6 | Liquiritigenin | C15H12O4 | 256.1 | 257.0 [M+H]+ |

| 7 | Glycyrrhizin | C42H62O16 | 822.4 | 823.2 [M+H]+ |

3.2. Analytical methods validation

3.2.1. Selectivity

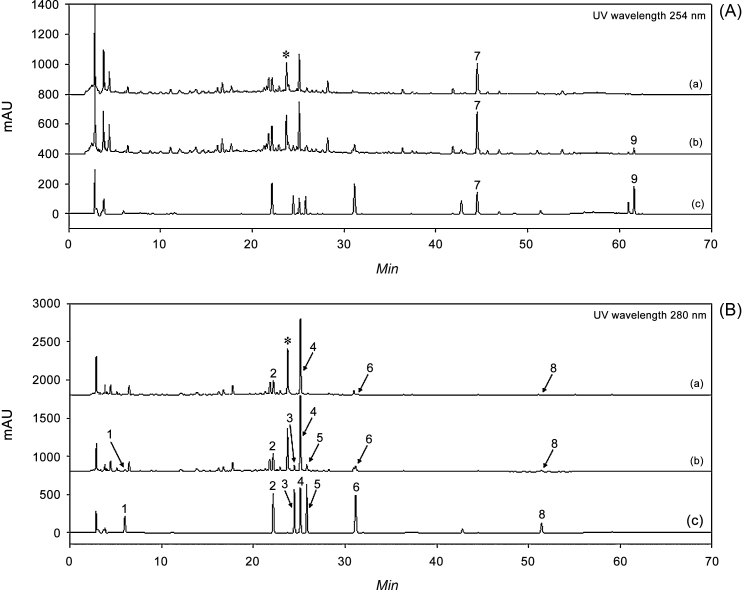

The identification of the nine bioactives was based on comparisons of their retention times (tR), UV spectra, and chromatograms with those of each standard. As shown in Fig. 3, the retention time of the compounds, homogentisic acid (1, 5.95 minutes), liquiritin (2, 22.13 minutes), naringin (3, 24.47 minutes), hesperidin (4, 25.11 minutes), neohesperidin (5, 25.81 minutes), liquiritigenin (6, 31.07 minutes), glycyrrhizin (7, 44.58 minutes), 6-gingerol (8, 51.31 minutes), and pachymic acid (9, 61.51 minutes) were well separated, within 60 minutes, and showed good selectivity, without interference by other analytes. The UV wavelength of the nine bioactive compounds was optimized according to the maximum absorption UV spectrum of each. Analytes (7) and (9) were detected at 254 nm, and (1–6) and (8) were detected at 280 nm. These results indicated that the method shows acceptable selectivity and specificity.

Fig. 3.

High-performance liquid chromatography-diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD) chromatogram of the nine components (1, homogentisic acid; 2, liquiritin; 3, naringin; 4, hesperidin; 5, neohesperidin; 6, liquiritigenin; 7, glycyrrhizin; 8, 6-gingerol, and 9, pachymic acid) in Yijin-tang (YJ) samples. The UV wavelength was set at (A) 254 nm and (B) 280 nm, (a) YJ control sample, (b) YJ control sample spiked with standard mixture, (c) standard mixture.

* Unknown peak.

3.2.2. Linearity, LLOD, and LLOQ

The linearity of the method was assessed in triplicate with six different concentrations of the standard solutions mixture. The results of linearity, LLOD, and LLOQ for each analyte are summarized in Table 3. Excellent linearity of the method was confirmed by the correlation coefficients (r2 ≥ 0.9995). The values of LLOD and LLOQ were in the ranges of 0.03–0.17 μg/mL and 0.09–0.43 μg/mL, respectively. The results showed that the calibration curves were within the adequate range and exhibited good sensitivity for the analysis of the nine bioactive components.

Table 3.

Calibration curves, lower limit of detection (LLOD) and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of the nine analytes

| Analyte | Regression equation* | Correlation coefficient (r2) | Linear range (μg) | LLOD (μg/mL) | LLOQ (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogentisic acid | y = 21,178.81 x + 6,992.74 | 0.9995 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Liquiritin | y = 68,007.99 x + 7,479.75 | 1.0000 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Naringin | y = 62,510.77 x + 6,691.15 | 1.0000 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Hesperidin | y = 60,914.20 x + 27,066.04 | 1.0000 | 1.11–88.89 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| Neohesperidin | y = 73,062.94 x + 8,067.88 | 1.0000 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Liquiritigenin | y = 90,170.91 x + 9,631.00 | 1.0000 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Glycyrrhizin | y = 22,633.10 x + 13,541.15 | 0.9997 | 0.83–66.67 | 0.17 | 0.41 |

| 6-Gingerol | y = 24,815.32 x + 5,641.04 | 1.0000 | 0.28–22.22 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| Pachymic acid | y = 4,847.30 x – 959.46 | 1.0000 | 0.56–44.44 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

Y, peak area; x, concentration (μg/mL).

3.2.3. Precision and accuracy

Results of the intra- and interday precision tests are shown in Table 4. The values of RSD (%) for intra- and interday tests were within the ranges of 0.09–1.19% and 0.04–1.00%, with accuracy from 100.38% to 105.86% and 98.12% to 105.43%, respectively. The values of RSD were < 2.0%, and were thus within the standards of the guideline.27 These results indicated that this method was accurate and reliable for all the analytes.

Table 4.

Precision (intra- and interday) and accuracy of the nine analytes

| Analyte | Analyte concentration (μg/mL) | Intraday (n = 5) |

Interday (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated concentration (mean ± SD, μg/mL) | RSD (%) | Accuracy (%) | Calculated concentration (mean ± SD, μg/mL) | RSD (%) | Accuracy (%) | ||

| Homogentisic acid | 2.78 | 2.82 ± 0.02 | 0.85 | 101.69 | 2.84 ± 0.01 | 0.16 | 102.12 |

| 5.56 | 5.76 ± 0.04 | 0.75 | 103.61 | 5.60 ± 0.05 | 0.91 | 100.87 | |

| 11.11 | 11.37 ± 0.06 | 0.55 | 102.34 | 10.90 ± 0.08 | 0.75 | 98.12 | |

| Liquiritin | 2.78 | 2.79 ± 0.01 | 0.25 | 100.60 | 2.81 ± 0.01 | 0.40 | 100.99 |

| 5.56 | 5.69 ± 0.07 | 1.19 | 102.34 | 5.71 ± 0.01 | 0.13 | 102.81 | |

| 11.11 | 11.42 ± 0.03 | 0.24 | 102.82 | 11.44 ± 0.01 | 0.04 | 102.96 | |

| Naringin | 2.78 | 2.87 ± 0.01 | 0.35 | 103.45 | 2.89 ± 0.01 | 0.25 | 104.12 |

| 5.56 | 5.67 ± 0.03 | 0.61 | 102.08 | 5.63 ± 0.02 | 0.43 | 101.27 | |

| 11.11 | 11.49 ± 0.01 | 0.11 | 103.40 | 11.35 ± 0.01 | 0.09 | 102.14 | |

| Hesperidin | 11.11 | 11.76 ± 0.03 | 0.27 | 105.86 | 11.71 ± 0.02 | 0.17 | 105.43 |

| 22.22 | 23.46 ± 0.16 | 0.68 | 105.55 | 23.24 ± 0.10 | 0.41 | 104.57 | |

| 44.44 | 46.39 ± 0.19 | 0.40 | 104.38 | 46.36 ± 0.15 | 0.33 | 104.32 | |

| Neohesperidin | 2.78 | 2.86 ± 0.02 | 0.58 | 103.08 | 2.88 ± 0.01 | 0.20 | 103.54 |

| 5.56 | 5.69 ± 0.03 | 0.59 | 102.47 | 5.70 ± 0.02 | 0.38 | 102.67 | |

| 11.11 | 11.46 ± 0.02 | 0.15 | 103.10 | 11.32 ± 0.03 | 0.26 | 101.86 | |

| Liquiritigenin | 2.78 | 2.90 ± 0.02 | 0.65 | 104.31 | 2.88 ± 0.01 | 0.31 | 103.73 |

| 5.56 | 5.80 ± 0.01 | 0.13 | 104.48 | 5.74 ± 0.04 | 0.61 | 103.34 | |

| 11.11 | 11.60 ± 0.05 | 0.44 | 104.41 | 11.44 ± 0.01 | 0.04 | 102.92 | |

| Glycyrrhizin | 8.33 | 8.45 ± 0.05 | 0.57 | 101.37 | 8.46 ± 0.01 | 0.15 | 101.50 |

| 16.67 | 17.08 ± 0.01 | 0.09 | 102.50 | 16.96 ± 0.01 | 0.06 | 101.74 | |

| 33.33 | 33.70 ± 0.07 | 0.21 | 101.09 | 33.68 ± 0.07 | 0.20 | 101.03 | |

| 6-Gingerol | 2.78 | 2.85 ± 0.01 | 0.09 | 102.65 | 2.85 ± 0.01 | 0.20 | 102.53 |

| 5.56 | 5.60 ± 0.02 | 0.33 | 100.84 | 5.62 ± 0.06 | 1.00 | 101.18 | |

| 11.11 | 11.40 ± 0.04 | 0.31 | 102.58 | 11.23 ± 0.03 | 0.30 | 101.06 | |

| Pachymic acid | 5.56 | 5.61 ± 0.03 | 0.59 | 100.98 | 5.60 ± 0.02 | 0.42 | 100.88 |

| 11.11 | 11.15 ± 0.05 | 0.41 | 100.38 | 11.20 ± 0.04 | 0.37 | 100.80 | |

| 22.22 | 22.56 ± 0.05 | 0.21 | 101.32 | 22.47 ± 0.05 | 0.22 | 101.11 | |

RSD, relative standard deviation; SD, standard deviation.

3.2.4. Recovery

The average recovery (%) of each analyte showed the accuracy of this analytical method. The average recovery ranged from 97.65% to 104.50%, and the values of RSD were < 1.43%. These results are summarized in Table 5. Thus, no significant matrix effect was found, indicating that no internal interference was detected for any of the analytes.

Table 5.

Recoveries of the nine analytes

| Analyte | Spiked amount (μg/mL) | Measured amount (μg/mL) | RSD (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogentisic acid | 1.39 | 1.40 ± 0.01 | 0.15 | 100.58 |

| 2.78 | 2.82 ± 0.02 | 0.59 | 101.44 | |

| 5.56 | 5.61 ± 0.02 | 0.42 | 101.01 | |

| Liquiritin | 1.39 | 1.44 ± 0.01 | 0.43 | 103.42 |

| 2.78 | 2.83 ± 0.02 | 0.74 | 102.05 | |

| 5.56 | 5.81 ± 0.03 | 0.53 | 104.50 | |

| Naringin | 1.39 | 1.41 ± 0.01 | 0.22 | 101.44 |

| 2.78 | 2.85 ± 0.02 | 0.68 | 102.68 | |

| 5.56 | 5.45 ± 0.01 | 0.32 | 98.07 | |

| Hesperidin | 5.56 | 5.67 ± 0.04 | 0.78 | 102.10 |

| 11.11 | 11.45 ± 0.06 | 0.54 | 103.01 | |

| 22.22 | 22.99 ± 0.16 | 0.70 | 103.46 | |

| Neohesperidin | 1.39 | 1.42 ± 0.01 | 0.79 | 102.22 |

| 2.78 | 2.83 ± 0.01 | 0.46 | 101.82 | |

| 5.56 | 5.70 ± 0.01 | 0.05 | 102.64 | |

| Liquiritigenin | 1.39 | 1.44 ± 0.01 | 0.47 | 103.72 |

| 2.78 | 2.85 ± 0.01 | 0.17 | 102.55 | |

| 5.56 | 5.70 ± 0.02 | 0.28 | 102.60 | |

| Glycyrrhizin | 4.17 | 4.26 ± 0.05 | 1.20 | 102.20 |

| 8.33 | 8.53 ± 0.05 | 0.56 | 102.37 | |

| 16.67 | 16.74 ± 0.04 | 0.22 | 100.45 | |

| 6-Gingerol | 1.39 | 1.38 ± 0.02 | 1.43 | 99.31 |

| 2.78 | 2.78 ± 0.01 | 0.25 | 100.03 | |

| 5.56 | 5.43 ± 0.04 | 0.76 | 97.65 | |

| Pachymic acid | 2.78 | 2.81 ± 0.02 | 0.55 | 101.08 |

| 5.56 | 5.71 ± 0.02 | 0.35 | 102.75 | |

| 11.11 | 11.06 ± 0.04 | 0.37 | 99.58 |

RSD, relative standard deviation.

3.3. Analysis of YJ and fermented YJ samples

The established HPLC-DAD and LC/MS method was used for analyses of the nine bioactive compounds in YJ control and f-YJ samples. The contents of the nine standard compounds were determined with the calibration curves of the standards. The results of quantitative analyses of the YJ and f-YJ samples are shown in Table 6, along with the concentrations of the nine biomarkers in each sample. Homogentisic acid, naringin, neohesperidin, and pachymic acid were present in the HPLC chromatograms of the YJ samples, but their contents were below the LLOQ, and so are listed as “nd” (not detected). As shown in Table 7, fermentation by Lacobacillus species led to a marked decrease in liquiritin and liquiritigenin levels.

Table 6.

Amounts of nine analytes in Yijin-Tang (YJ) and YJ fermented by various Lactobacillus strains

| Strains | Amounts (μg/g extract) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homogentisic acid | Liquiritin | Naringin | Hesperidin | Neohesperidin | Liquiritigenin | Glycyrrhizin | 6-Gingerol | Pachymic acid | |

| Control | n.d. | 2.542 | n.d. | 14.661 | n.d. | 0.680 | 6.305 | 0.113 | n.d. |

| L. rhamnosus KFRI 144 | n.d. | 0.267 | n.d. | 13.613 | n.d. | 2.470 | 4.171 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. acidophilus KFRI 150 | n.d. | 0.532 | n.d. | 13.271 | n.d. | 2.397 | 7.974 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. amylophilus KFRI 161 | n.d. | 0.402 | n.d. | 13.248 | n.d. | 2.262 | 4.104 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. acidophilus KFRI 162 | n.d. | 0.356 | n.d. | 13.571 | n.d. | 2.412 | 4.221 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. plantarum KFRI 166 | n.d. | 0.249 | n.d. | 13.445 | n.d. | 2.394 | 3.563 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. acidophilus KFRI 217 | n.d. | 0.432 | n.d. | 13.502 | n.d. | 2.255 | 3.482 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. brevis KFRI 221 | n.d. | 0.358 | n.d. | 14.475 | n.d. | 2.660 | 5.429 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. brevis KFRI 227 | n.d. | 0.363 | n.d. | 13.064 | n.d. | 2.434 | 7.721 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. curvatus KFRI 231 | n.d. | 0.391 | n.d. | 13.725 | n.d. | 1.635 | 3.859 | n.d. | n.d. |

| L. acidophilus KFRI 341 | n.d. | 0.643 | n.d. | 13.380 | n.d. | 2.039 | 4.013 | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d., not detected.

Table 7.

Conversion rate of liquiritin and liquiritigenin in fermented-YJ (f-YJ) samples

| Strains | Conversion rate (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Liquiritin | Liquiritigenin | |

| Control | ||

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus KFRI 144 | –89.51 | 263.14 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI 150 | –79.09 | 252.40 |

| Lactobacillus amylophilus KFRI 161 | –84.21 | 232.58 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI 162 | –85.98 | 254.62 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum KFRI 166 | –90.20 | 252.06 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI 217 | –83.01 | 231.61 |

| Lactobacillus brevis KFRI 221 | –85.92 | 291.08 |

| Lactobacillus. brevis KFRI 227 | –85.73 | 257.94 |

| Lactobacillus curvatus KFRI 231 | –84.62 | 140.47 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus KFRI 341 | –74.72 | 199.86 |

4. Discussion

A reliable, simple, and sensitive HPLC-DAD and LC/MS method was developed for the simultaneous quantitation of nine biomarkers, including homogentisic acid, liquiritin, naringin, hesperidin, neohesperidin, liquiritigenin, glycyrrhizin, 6-gingerol, and pachymic acid in YJ. The HPLC-DAD method was validated and the results showed good linearity, precision, and accuracy, with RSD < 2%. Furthermore, no remarkable internal interferences were detected. The method was applied to the simultaneous determination of these nine components in YJ and f-YJ samples. Moreover, biomarkers were identified and quantified based on UV absorbance spectra, retention times, and mass spectra by comparisons with standard compounds. The results show that our method is an efficient tool that is suitable for the quality control of YJ. Note, however, that an unknown peak in the HPLC-DAD chromatogram (Fig. 3) was observed at 23.7 minutes. Further study, including chemical profiling of YJ via tandem MS chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance, is required to identify this unknown material.

To optimize the quality control of YJ, we selected biomarkers for five herbal medicines within YJ (Table 1). Variations in the amounts of these nine components in YJ, and f-YJ samples produced by Lactobacillus KFRI strains, were analyzed and are compared in Table 6. Hesperidin (for C. unshiu Markovich), 6-gingerol (for Z. officinale Roscoe), and liquiritin, liquiritigenin, and glycyrrhizin (for G. uralensis Fisch) were detected with good sensitivity in YJ samples. Hesperidin, a main flavanone glycoside in C. unshiu Markovich, was the most abundant component in YJ samples at 11.98–14.66 mg/g of dry weight.5, 6 We isolated varying amounts of liquiritin, liquiritigenin, and glycyrrhizin for G. uralensis Fisch, ranging from 0.249 mg/g to 2.542 mg/g, 0.680 mg/g to 2.660 mg/g, and 3.563 mg/g to 6.305 mg/g of dry weight, respectively. These results suggest that the detected analytes could be used as YJ biomarkers for herbal medicines. Unfortunately, homogentisic acid from P. ternata Breitenbach, naringin and neohesperidin from C. unshiu Markovich, and pachymic acid from P. cocos Wolf were not detected in YJ samples. However, the contents of bioactive compounds in herbal medicines can differ as functions of collection period, region, species, and preparation method.29 This validated analytical method for naringin, neohesperidin, and pachymic acid is therefore a useful tool for evaluating C. unshiu Markovich- and P. cocos Wolf-containing herbal medicines.

In Table 7, liquiritin in f-YJ samples decreased up to ∼90%, whereas liquiritigenin, its aglycone form increased by 291.08% compared to the control. According to literature reports, the deglycosylation activity of glycosides (e.g., liquiritin) is influenced by the activity of β-glycosidase, which is produced by lactic acid bacteria during fermentation.30, 31, 32 These findings imply that liquiritin is a good indicator of fermentation, as it is converted to liquiritigenin by Lactobacillus species. The intestinal absorption of aglycone forms is faster and greater than their glycosidic equivalents in vivo, thereby increasing bioavailability and therapeutic efficiency.33, 34, 35, 36 By contrast, the concentrations of hesperidin and 6-gingerol in YJ samples were lower after fermentation. We consider that these components were converted into aglycones (e.g., hesperetin, α-, β-glycyrrhetinic acid) or other chemical forms by microbial mechanisms or through enzymatic hydrolysis.31, 37 Further studies should be conducted to elucidate this phenomenon.

In conclusion, we established five biomarkers for YJ-composed herbal medicines and developed a novel HPLC-DAD and LC-MS method for the simultaneous determination of nine biomarkers in YJ. For the purposes of efficient quality control prior to pharmacological evaluation, this HPLC method was successfully applied to qualitative and quantitative analyses of nine bioactive compounds in YJ and f-YJ.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grant (K15280) from the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning, Republic of Korea.

Contributor Information

Youn-Hwan Hwang, Email: hyhhwang@kiom.re.kr.

Jin Yeul Ma, Email: jyma@kiom.re.kr.

References

- 1.Katagiri F., Inoue S., Sato Y., Itoh H., Takeyama M. The Effect of Nichin-to on the Plasma Gut-Regulatory Peptide Level in Healthy Human Subjects. J Health Sci. 2005;51:172–177. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S.J., Kim S.G. Effects of the Ijintang, Sagoonjatang, and Yuggoonjatang on the hyperlipidemia induced rabbits. J Korean Orient Intern Med. 1994;15:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi J.W., Lee C.H., Ko B.M., Lee K.G. Effects of Yijin-tang extract on the immunoreactive cells of gastrin, histamine and somatostatin in rats stomach. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2001;15:554–559. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q., Ye M. Chemical analysis of the Chinese herbal medicine Gan-Cao (licorice) J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:1954–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Y., Zhang C., Bucheli P., Wei D. Citrus flavonoids in fruit and traditional Chinese medicinal food ingredients in China. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2006;61:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s11130-006-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y.Q., Ye X.Q., Fang Z.X., Chen J.C., Xu G.H., Liu D.H. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of extracts from ultrasonic treatment of Satsuma Mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.) peels. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:5682–5690. doi: 10.1021/jf072474o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamdan D., El-Readi M.Z., Tahrani A., Herrmann F., Kaufmann D., Farrag N. Chemical composition and biological activity of Citrus jambhiri Lush. Food Chem. 2011;127:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Y., Yang X.W. Two new lanostane triterpenoids from Poria cocos. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2008;10:323–328. doi: 10.1080/10286020801892250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoyama Y., Nishioka I., Hatano K. Micropropagation of Pinellia ternate. Biotechnol Agric For. 1992;19:464–480. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J.S., Lee S.I., Park H.W., Yang J.H., Shin T.Y., Kim Y.C. Cytotoxic components from the dried rhizomes of Zingiber officinale Roscoe. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:415–418. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1172-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K.J., Choi J.S., Kim K.W., Jeong J.W. The anti-angiogenic activities of glycyrrhizic acid in tumor progression. Phytother Res. 2013;27:841–846. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirata T., Fujii M., Akita K., Yanaka N., Ogawa K., Kuroyanagi M. Identification and physiological evaluation of the components from Citrus fruits as potential drugs for anti-corpulence and anticancer. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai T., Kiyohara H., Munakata K., Shirahata T., Sunazuka T., Harigaya Y., Yamada H. Pinellic acid from the tuber of Pinellia ternata Breitenbach as an effective oral adjuvant for nasal influenza vaccine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugasani S., Pichika M.R., Nadarajah V.D., Balijepalli M.K., Tandra S., Korlakunta J.N. Comparative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of [6]-gingerol, [8]-gingerol, [10]-gingerol and [6]-shogaol. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng S., Eliaz I., Lin J., Sliva D. Triterpenes from Poria cocos suppress growth and invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells through the downregulation of MMP-7. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1869–1874. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee Y.H., Lee N.H., Bhattarai G., Kim G.E., Lee I.K., Yun B.S. Anti-inflammatory effect of pachymic acid promotes odontoblastic differentiation via HO-1 in dental pulp cells. Oral Dis. 2013;19:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li T., Yan Z., Zhou C., Sun J., Jiang C., Yang X. Simultaneous quantification of paeoniflorin, nobiletin, tangeretin, liquiritigenin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritin and formononetin from Si-Ni-San extract in rat plasma and tissues by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27:1041–1053. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen L., Cong W.J., Lin X., Hong Y.L., Hu R.W., Feng Y. Characterization using LC/MS of the absorption compounds and metabolites in rat plasma after oral administration of a single or mixed decoction of Shaoyao and Gancao. Chem Pharm Bull. 2012;60:712–721. doi: 10.1248/cpb.60.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farag M.A., Porzel A., Wessjohann L.A. Comparative metabolite profiling and fingerprinting of medicinal licorice roots using a multiplex approach of GC–MS, LC–MS and 1D NMR techniques. Phytochemistry. 2012;76:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong L., Zhou D., Gao J., Zhu Y., Sun H., Bi K. Simultaneous determination of naringin, hesperidin, neohesperidin, naringenin and hesperetin of Fractus aurantii extract in rat plasma by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2012;58:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu K.Y., Fu Q., Xie H.Q., Xu S.L., Cheung A.W.H., Zheng K.Y.Z. Quality assessment of a formulated Chinese herbal decoction, Kaixinsan, by using rapid resolution liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry: A chemical evaluation of different historical formulae. J Sep Sci. 2010;33:3666–3674. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoang L., Kwon S.H., Kim K.A., Hur J.M., Kang Y.H., Song K.S. Chemical standardization of Poria cocos. Kor J Phamacogn. 2005;36:177–185. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu W.Y., Chen C.M., Tsai F.J., Lai C.C. Simultaneous detection of diagnostic biomarkers of alkaptonuria, ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency, and neuroblastoma disease by high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;420:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao Y., Li W., Liang W., Breemen R.B.V. Identification and quantification of gingerols and related compounds in ginger dietary supplements using high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:10014–10021. doi: 10.1021/jf9020224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding L., Luo X., Tang F., Yuan J., Liu Q., Yao S. Simultaneous determination of flavonoid and alkaloid compounds in citrus herbs by high-performance liquid chromatography–photodiode array detection–electrospray mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2007;857:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S.S., Kim J.H., Shin H.K., Seo C.S. Simultaneous analysis of six compounds in Yijin-tang by HPLC-PDA. Herb Formula Sci. 2013;21:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) International Conference on Harmonisation; Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology Q2(R1) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan Z., Yang X., Wu J., Su H., Chen C., Chen Y. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of chemical constituents in traditional Chinese medicinal formula Tong-Xie-Yao-Fang by high-performance liquid chromatography/diode array detection/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;691:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S., Han Q., Qiao C., Song J., Lung C., Xu H. Chemical markers for the quality control of herbal medicines: an overview. Chin Med. 2008;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien H.L., Huang H.Y., Chou C.C. Transformation of isoflavone phytoestrogens during the fermentation of soymilk with lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Food Microbiol. 2006;23:772–778. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho C.W., Jeong H.C., Hong H.D., Kim Y.C., Choi S.Y., Kim K.T. Bioconversion of isoflavones during the fermentation of Samso-Eum with Lactobacillus strains. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2012;17:1062–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park M.J., Na I.S., Min J.W., Kim S.Y., Yang D.C. Biotransformation of liquiritin in Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch extract into liquiritigenin by plant crude enzymes. Korean J Med Crop Sci. 2008;16:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hur H.G., Lay J.O., Jr., Beger R.D., Freeman J.P., Rafii F. Isolation of human intestinal bacteria metabolizing the natural isoflavone glycosides daidzin and genistin. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:422–428. doi: 10.1007/s002030000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim M.K., Lee J.W., Lee K.Y., Yang D.C. Microbial conversion of major ginsenoside Rb1 to pharmaceutically active minor ginsenoside Rd. J Microbiol. 2005;43:456–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Na I.S., Park M.J., Noh C.H., Min J.W., Bang M.H., Yang D.C. Production of flavonoid aglycone from Korean Glycyrrhizae radix by biofermentation process. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2008;22:569–574. [In Korean, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Booth C., Hargreaves D.F., Hadfield J.A., McGown A.T., Potten C.S. Isoflavones inhibit intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in vitro. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1550–1557. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzanares P., van den Broeck H.C., de Graaff L.H., Visser J. Purification and characterization of two different α-L-rhamnosidases, RhaA and RhaB, from Aspergillus aculeatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2230–2234. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2230-2234.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]