Abstract

Epidemiological studies evaluating the association between the intake of vitamin C and lung cancer risk have produced inconsistent results. We conducted a meta-analysis to assess the association between them. Pertinent studies were identified by a search of PubMed, Web of Knowledge and Wan Fang Med Online through December of 2013. Random-effect model was used to combine the data for analysis. Publication bias was estimated using Begg's funnel plot and Egger's regression asymmetry test. Eighteen articles reporting 21 studies involving 8938 lung cancer cases were included in this meta-analysis. Pooled results suggested that highest vitamin C intake level versus lowest level was significantly associated with the risk of lung cancer [summary relative risk (RR) = 0.829, 95%CI = 0.734–0.937, I2 = 57.8%], especially in the United States and in prospective studies. A linear dose-response relationship was found, with the risk of lung cancer decreasing by 7% for every 100 mg/day increase in the intake of vitamin C [summary RR = 0.93, 95%CI = 0.88–0.98]. No publication bias was found. Our analysis suggested that the higher intake of vitamin C might have a protective effect against lung cancer, especially in the United States, although this conclusion needs to be confirmed.

Lung cancer accounts for a significant proportion of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with an estimated 1.3 million newly diagnosed cases each year; furthermore, the overall survival rate for lung cancer patients is extremely low1. The age-adjusted incidence rate of lung cancer was recently reported at 62.6 cases per 100,000 people per year, and the age-adjusted death rate at 50.6 per 100,000 people per year2. Thus, primary prevention of lung cancer is critical. Many studies have shown that lung cancer is associated with genetic factors3,4, and environmental factors including tobacco use5, alcohol consumption6, and intake of fruit, vegetables7 and vitamins8,9 can also affect the incidence of lung cancer.

Vitamin C is one of the most common antioxidants in fruits and vegetables, and it may exert chemopreventive effects10. It has generally been acknowledged that vitamin C protects cells from oxidative DNA damage, thereby blocking carcinogenesis11. To date, a number of epidemiologic studies have been published exploring the relationship between vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk. However, the results of these studies are not consistent. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis in order to (1) assess lung cancer risk for the highest vs. lowest categories of vitamin C intake; (2) assess the dose-response association of lung cancer for every 100 mg/day increment in vitamin C intake; and (3) assess heterogeneity and publication bias among the studies we analyzed.

Methods

Search strategy

Studies were identified using a literature search of PubMed, Web of Knowledge and Wan Fang Med Online through December 2013, and by hand-searching the reference lists of the retrieved articles. The following search terms were used: ‘lung cancer’ or ‘lung carcinoma’ combined with ‘nutrition,’ ‘diet,’ ‘lifestyle,’ ‘vitamin C,’ ‘vitamins’ or ‘ascorbic acid’. Two investigators searched articles and reviewed all the retrieved studies independently. Disagreements between the two investigators were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer.

Study selection

For inclusion, studies had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) have a prospective or case-control study design; (2) vitamin C intake was the independent variable of interest; (3) the dependent variable of interest was lung cancer; (4) relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was provided; and (5) for dose-response analysis, the intake of vitamin C for each response category must also have been provided (or data available to calculate them). If data were replicated in more than one study, we included the study with the largest number of cases. Accordingly, the following exclusion criteria were also used: (1) reviews; (2) the RR or OR with 95%CI was not available and (3) repeated or overlapped publications.

Data extraction

Two researchers independently extracted the following data from each study that met the criteria for inclusion: the first author's last name, year of publication, geographic locations, study design, sample source, the age range of study participants, duration of follow-up, the number of cases and participants (person-years), and RR (95%CI) for each category of vitamin C. From each study, we extracted the RR that reflected the greatest degree of control for potential confounders. If there was disagreement between the two investigators about eligibility of the data, it was resolved by consensus with a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

The pooled measure was calculated as the inverse variance-weighted mean of the logarithm of RR with 95% CI, to assess the association between vitamin C intake and the risk of lung cancer. Random-effects model was used to combine study-specific RR (95%CI), which considers both within-study and between-study variation12. The I2 was used to assess heterogeneity, and I2 values of 0, 25, 50 and 75% represent no, low, moderate and high heterogeneity13, respectively. Meta-regression with restricted maximum likelihood estimation was performed to assess the potentially important covariates that might exert substantial impact on between-study heterogeneity14. If no significant covariates were found to be heterogeneous, the “leave-one-out” sensitive analysis15 was carried out to evaluate the key studies with substantial impact on between-study heterogeneity. Publication bias was evaluated using Begg's funnel plot16 and Egger regression asymmetry test17. A study of influence analysis18 was conducted to describe how robust the pooled estimator was to removal of individual studies. An individual study was suspected of excessive influence if the point estimate of its omitted analysis lay outside the 95% CI of the combined analysis.

For the dose-response analysis, the method reported by Greenland et al.19 and Orsini et al.20 was used to calculate study specific slopes (linear trends) based on the results across categories of vitamin C intake. The method requires that the distribution of cases and person-years or non-cases and the RR with the variance estimates for at least three quantitative exposure categories are known. When this information was not available, we estimated the slopes (linear trends) by using variance-weighted least squares regression analysis21,22. The median or mean level of vitamin C in each category was assigned to the corresponding RR with 95% CI for each study. When vitamin C was reported by range of intake in the paper, the midpoint of the range was used. When the highest category was open-ended, we assumed the width of the category to be the same as that of the adjacent category. When the lowest category was open-ended, we set the lower boundary to zero23,24. The dose-response results in forest plots are presented for every 100 mg/day increment in vitamin C intake. A potential curve linear dose-response relation between vitamin C and lung cancer risk was examined by using restricted cubic spline model with three knots at the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles25 of the distribution. A P-value for non-linearity was calculated by testing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the second spline is equal to zero. All statistical analyses were conducted with STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Two-tailed P ≤ 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

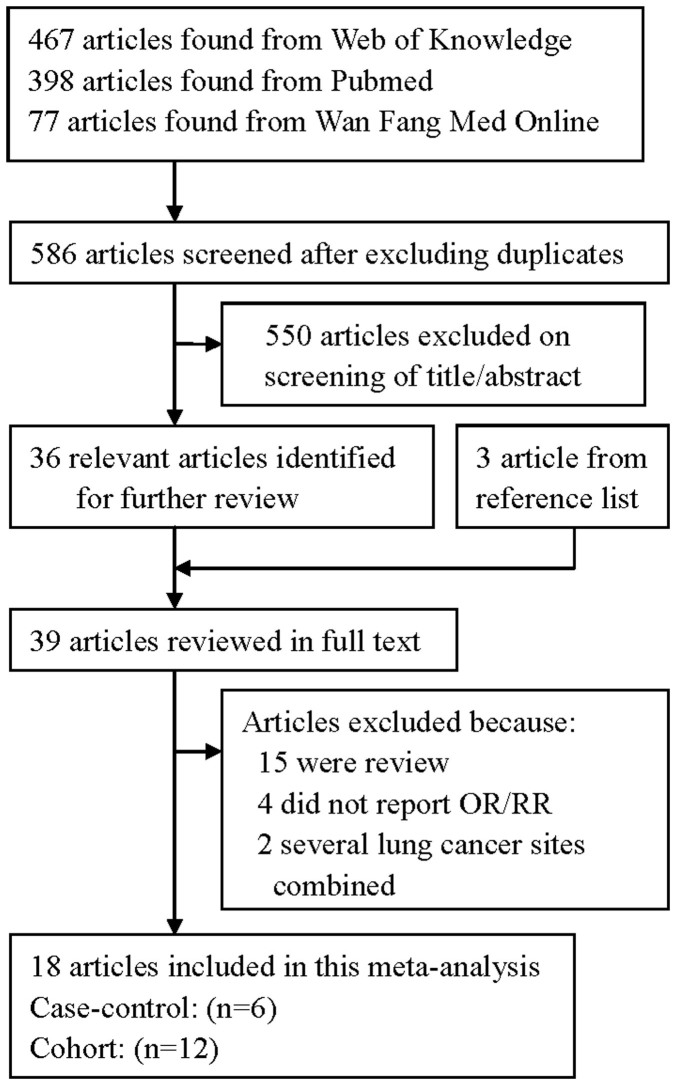

The search strategy identified 398 articles from Pubmed, 77 from Wan Fang Med Online and 467 from the Web of Knowledge; 36 articles were reviewed in full after reviewing the title/abstract. By studying reference lists, we identified 3 additional articles. Twenty-one of these 39 articles were subsequently excluded from the meta-analysis for various reasons. In total, 18 articles26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 reporting 21 studies (14 prospective studies and 7 case-control studies) involving 8938 lung cancer cases were used in this meta-analysis. The detailed steps of our literature search are shown in Figure 1. The characteristics of these studies are presented in Table 1. Fifteen studies were conducted in the United States, two in the Netherlands, two in China, one in Canada and one in Uruguay.

Figure 1. The flow diagram of screened, excluded, and analyzed publications.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies on vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk.

| Study, year | Country | Study design | Participants (cases) | Age (years) | RR (95%CI) for highest versus lowest category | Adjustment for covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bandera et al.1997 | United States | Prospective (PNCC) | 48,000 (525) | 40–80 | 0.63(0.53–0.88) for males | Adjusted for age, education, cigarettes/day, years smoking, and total energy intake (except calories) based on Cox Proportional Hazards Model. |

| 0.88(0.57–1.37) for females | ||||||

| Candelora et al. 1992 | United States | Case-control (PCC) | 387 (124) | Case: 71.9 Control: 69.8 | 0.5(0.3–1.0) | Adjusted for age, education (≤8 and >8 grades), and total calories. |

| Feskanich et al. 2000 | United States | Prospective | 125,061 (793) | 30–75 | 1.04(0.71–1.53) for males | Adjusted for age, follow-up cycle, smoking status, years since quitting among past smokers, cigarettes smoked/day among current smokers, age at start of smoking, total energy intake, and availability of diet data after baseline measure. |

| 0.82(0.62–1.10) for females | ||||||

| Fontham et al. 1988 | United States | Case-control (HCC) | 2,527 (1,253) | <40-≥70 | 0.67(0.53–0.84) | Adjusted in logistic regression model for age, race, sex, and pack years of cigarette use. |

| Gaziano et al. 2009 | United States | Prospective | 14,641 (50) | ≥50 | 0.95(0.64–1.39) | Adjusted for age, PHS cohort (original PHS I participant, new PHS participant), and randomized treatment assignment (beta-carotene, multivitamin, and either vitamin E or vitamin C); and stratified on baseline cancer. |

| Jain et al. 1990 | Canada | Case-control (PCC) | 1,611 (839) | 20–75 | 1.08(0.86–1.36) | Adjusted for cumulative cigarette smoking |

| Hinds et al. 1984 | United States | Case-control (PCC) | 991 (364) | ≥30 | 0.77(0.42–1.39) | Adjustment by multiple logistic regression for age, ethnicity, cholesterol intake, occupational status, vitamin A intake, pack-years of cigarette smoking, and sex where appropriate. |

| Le Marchand et al. 1989 | United States | Case-control (PCC) | 1,197 (332) | 30–85 | 0.50(0.28–0.90) for males | Adjusted for age, ethnicity, smoking status, pack-years of cigarette smoking, cholesterol intake (for males only), and intakes of other nutrients in the table. |

| 2.50(1.12–5.59) for females | ||||||

| Neuhouser et al. 2003 | United States | Prospective | 14,120 (742) | Case: 60.4 Control: 57.6 | 0.66(0.47–0.94) | Adjusted for sex, age, smoking status, total pack-years of smoking, asbestos exposure, race/ethnicity, and enrollment center. |

| Ocke et al. 1997 | Netherlands | Prospective | 561 (54) | Case: 59.3 Control: 59.5 | 0.46(0.24–0.88) | Adjusted for age, pack-years of cigarettes, and energy intake, |

| Slatore et al. 2008 | United States | Prospective | 77,721 (521) | 50–76 | 0.97(0.76–1.23) | Adjusted for age, sex, years smoked, pack-years, and pack-years squared. |

| Speizer et al. 1999 | United States | Prospective | 121,700 (593) | 30–55 | 1.35(1.00–1.80) | Age, total energy intake, smoking (past and current amount in 1980; 1 ± 4, 5 ± 14, 15 ± 24, 25 ± 34, 35 ± 44, 45+) and age of starting to smoke. |

| Stefani et al. 1999 | Uruguay | Case-control (HCC) | 981 (541) | 30–89 | 1.03(0.70–1.52) | Adjusted for age, residence, urban/rural status, education, family history of a lung cancer in 1st-degree relative, body mass index, tobacco smoking (pack-yr), and total energy and total fat intakes, IQR, interquartile range. |

| Steinmetz et al. 1993 | United States | Prospective | 41,837 (179) | 55–69 | 0.81(0.46–1.43) | Adjusted by inclusion of continuous variables for age, energy intake, and pack-years of smoking in multivariale logistic regression models. |

| Takata et al. 2013 | China | Prospective | 61,491 (359) | 40–74 | 0.84(0.61–1.16) | Adjusted for age, years of smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day, current smoking status, total caloric intake, education, BMI category, ever consumption of tea, history of chronic bronchitis, and family history of lung cancer among first-degree relatives. |

| Voorrips et al. 2000 | Netherlands | Prospective | 58,279 (939) | 55–69 | 0.77(0.54–1.08) | Adjusted for current smoking, years of smoking cigarettes, number of cigarettes per day, highest educational level, family history of lung cancer, and age. |

| Yong et al. 1997 | United States | Prospective | 1,068 (248) | 25–74 | 0.66(0.45–0.96) | Adjusted for sex race, educational attainment, nonrecreabonal activity level, body masa index, family history, smoking status/pack-years of smoking, total calorie intake, and alcohol intake. |

| Yuan et al. 2003 | China | Prospective | 63,257 (482) | 45–74 | 0.81(0.59–1.09) | Adjusted for age at baseline, sex, dialect group, year of interview, level of education, and BMI, number of cigarettes smoked per day, number of years of smoking, and number of years since quitting smoking for former smokers. |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; PNCC = population-based nested case–control study; HCC = hospital-based case–control study; PCC = population-based case–control study; RR = relative risk.

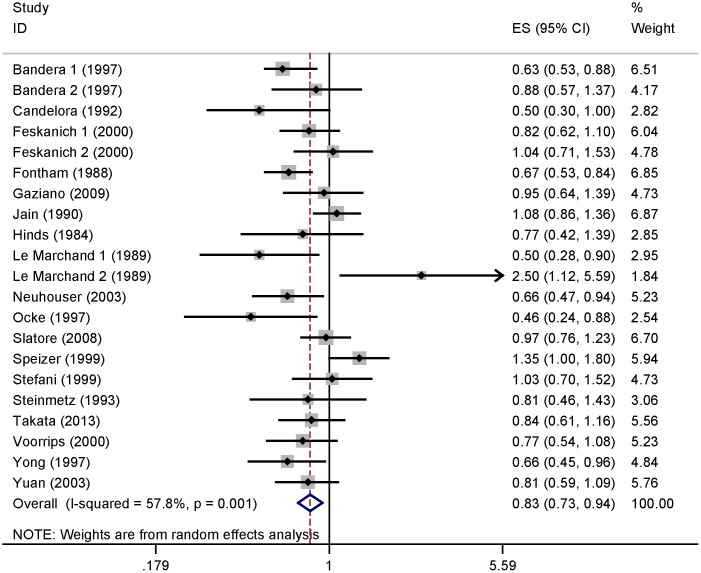

Analysis of high versus low vitamin C

Six of the studies included in our analysis reported an inverse association of vitamin C intake with the risk of lung cancer. No significant association was reported in 13 studies, while 2 studies reported that high vitamin C intake could increase the risk of lung cancer. Our pooled results suggested that the highest vitamin C intake level compared to the lowest level was significantly associated with the risk of lung cancer [summary RR = 0.829, 95%CI = 0.734–0.937, I2 = 57.8%] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The forest plot between highest versus lowest categories of vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk.

Studies are subgrouped according to design.

When the studies were stratified by study design, the association was also found in the prospective studies [summary RR = 0.829, 95%CI = 0.729–0.942] but not in the case-control studies. In subgroup analyses for geographic locations, an inverse association of vitamin C intake with risk of lung cancer was found in the United States [summary RR = 0.849, 95%CI = 0.735–0.982], but not in Europe or Asia. When we conducted the subgroup analysis by sex, a significant association was found in males [summary RR = 0.740, 95%CI = 0.631–0.868], but not in females. Furthermore, with stratification for histological type, associations were found with both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Details results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary risk estimates of the association between vitamin C and lung cancer risk.

| No. | No. | Heterogeneity test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroups | (cases) | studies | Risk estimate (95% CI) | I2 (%) | P-value |

| All studies | 8938 | 21 | 0.829(0.734–0.937) | 57.8 | 0.001 |

| Study design | |||||

| Prospective | 5485 | 14 | 0.829(0.729–0.942) | 48.0 | 0.023 |

| Case-control | 3453 | 7 | 0.838(0.620–1.133) | 73.2 | 0.001 |

| Geographic locations | |||||

| America | 7104 | 17 | 0.849(0.735–0.982) | 63.4 | 0.000 |

| Europe | 993 | 2 | 0.642(0.397–1.040) | 46.8 | 0.170 |

| Asia | 841 | 2 | 0.824(0.660–1.029) | 0.0 | 0.873 |

| Sex | |||||

| Males | 3474 | 8 | 0.740(0.631–0.868) | 31.9 | 0.173 |

| Females | 2037 | 8 | 0.999(0.751–1.329) | 59.5 | 0.016 |

| Histological type | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1009 | 3 | 0.634(0.524–0.768) | 0.0 | 0.852 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 482 | 3 | 0.713(0.549–0.926) | 0.0 | 0.632 |

| Sources of control (case-control studies) | |||||

| Population-based | 2184 | 7 | 0.808(0.590–1.107) | 73.4 | 0.001 |

| Hospital-based | 1794 | 2 | 0.807(0.531–1.225) | 71.4 | 0.062 |

| History of smoking | |||||

| Never-smokers | 262 | 3 | 1.025(0.640–1.642) | 0.0 | 0.474 |

| Current smokers | 1044 | 4 | 0.641(0.445–0.922) | 52.2 | 0.099 |

| Former smokers | 702 | 4 | 0.901(0.712–1.139) | 0.0 | 0.926 |

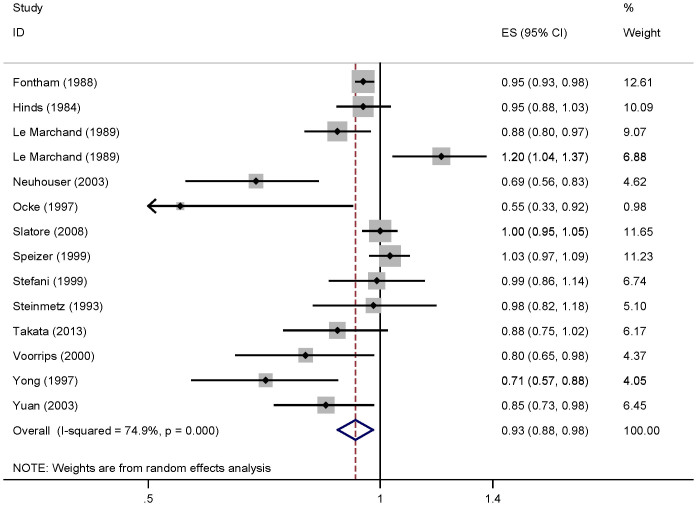

Dose-response analysis

For dose-response analysis, data from fourteen studies29,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 comprising 6607 cases were used for vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk. We found no evidence of statistically significant departure from linearity (P for nonlinearity = 0.24). Our dose-response analysis of vitamin C indicated that an increase in vitamin C intake of 100 mg/day was statistically significantly associated with a 7% decrease in the risk of developing lung cancer (summary RR = 0.93, 95%CI = 0.88–0.98; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dose-response meta-analyses of every 100 mg/day increased intake of vitamin C and the risk of lung cancer.

Squares represent study-specific RR, horizontal lines represent 95%CI and diamonds represent summary relative risks.

Sources of heterogeneity

As shown in Figure 2, evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 57.8%, Pheterogeneity = 0.001) was found in the pooled results. However, univariate meta-regression analysis, with the covariates of publication year, study design, geographic locations, sex and sources of controls showed no covariate having a significant impact on between-study heterogeneity. The key contributor to this high between-study heterogeneity assessed by the leave-one-out analysis was one study conducted by Speizer et al. (1999). After excluding this study, heterogeneity was reduced to I2 = 48.2%, and the summary RR for lung cancer was 0.805 (95%CI = 0.719–0.903).

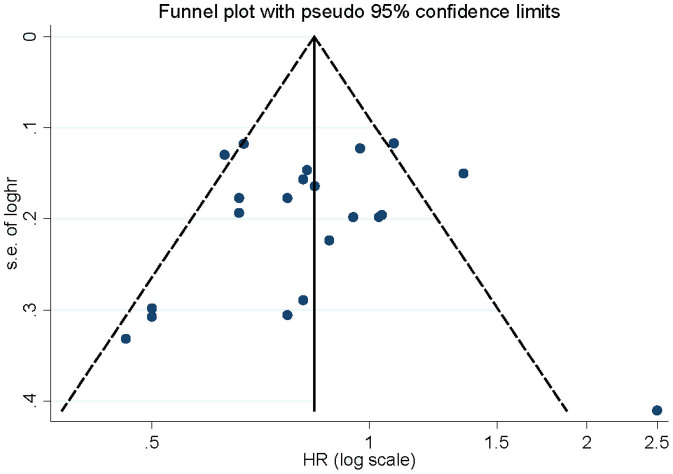

Influence analysis and publication bias

Influence analysis showed that no individual study exerted excessive influence on the association of vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk. Begg's funnel plot (Figure 4) and Egger's test (P = 0.654) showed no evidence of significant publication bias related to the association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk.

Figure 4. Begg's funnel plot for publication bias of vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk.

Discussion

Findings from this meta-analysis indicated that the highest vitamin C intake level versus the lowest level was significantly associated with the risk of lung cancer. Inverse associations were also found in prospective studies, geographic locations of the United States and in the subgroup of males. Our dose-response analysis demonstrated a linear relationship between vitamin C intake and the risk of lung cancer, with a decrease in risk of 7% for every 100 mg/day increase in the intake of vitamin C.

We found a significant association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer in the United States, from which most of the included studies (17 out of 21), and therefore most of the subjects. Only 2 studies came from Europe and 2 from Asia, in which we found no significant association, probably due to the small number of cases included. Due to this limitation, the results are applicable to the United States, but cannot be extended to populations elsewhere. More studies originating in other countries are required to investigate the association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk. As reported previously in 3 studies26,29,33, we conclude from our meta-analysis that the relationship between vitamin C and lung cancer is restricted to males, but not in the females.

Vitamin C is hypothesized to reduce the risk of cancer because of its role in quenching free radicals and reducing oxidative damage to DNA44,45,46. Previous meta-analysis has suggested that vitamin C intake reduces the risk of colorectal adenoma (RR = 0.78, 95%CI = 0.62–0.98)47, and that for gastric adenocarcinoma, each 20-μmol/L increase in plasma vitamin C was associated with a 14% decrease in risk (RR = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.76–0.96)48. Although no association was found between vitamin C intake and breast cancer in prospective studies, an inverse association of vitamin C intake with risk of breast cancer was found in case-control studies49. Meta-analysis has also suggested that the risk of endometrial cancer as estimated in dose-response models is reduced 15% for every 50 mg/1,000 kcal increase in intake of vitamin C (RR = 0.85; 95%CI = 0.73–0.98)50.

Munafo and Flint reported that between-study heterogeneity is common in meta-analyses51. Exploring potential sources of between-study heterogeneity is therefore an essential component of meta-analysis. We found a moderate degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 57.8%, Pheterogeneity = 0.001) in our pooled results. This might have arisen from publication year, study design, geographic location, sex, sources of controls or number of cases. Thus, we used meta-regression to explore the causes of heterogeneity for covariates. However, no covariate having a significant impact on between-study heterogeneity was found among those mentioned above. We then performed subgroup analyses by the type of study design (prospective or case-control studies), geographic locations, sex and sources of controls (population-based and hospital-based) to explore the source of heterogeneity. However, between-study heterogeneity persisted in some of the subgroups, suggesting the presence of other unknown confounding factors. The key contributor to this heterogeneity as assessed by the leave-one-out analysis was one study conducted by Speizer et al. (1999). After excluding this study, heterogeneity was reduced to I2 = 48.2%, without changing the results (RR = 0.805, 95%CI = 0.719–0.903).

We report here the first comprehensive meta-analysis of vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk based on high versus low analysis and dose-response meta-analysis. Our study included a larger number of participants than others, allowing a much greater possibility of reaching reliable conclusions about the association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk. There were some limitations in this meta-analysis. First, a meta-analysis of observational studies is susceptible to potential bias inherent in the original studies, especially for case-control studies. Several case-control studies were included in this meta-analysis, and no association was found between vitamin C intake and lung cancer risk in case-control studies. Second, as in any meta-analysis, the possibility of publication bias is of concern, because small studies with null results tend not to be published. However, the results obtained from Begg's funnel plot analysis and Egger's test did not provide evidence for such bias.

In summary, results from this meta-analysis suggest that a high intake of vitamin C might have a protective effect against lung cancer, especially in the United States. Dose-response analysis indicated that the estimated risk reduction in lung cancer is 7% for every 100 mg/day increase in intake of vitamin C.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.L. and D.Z. designed the experiments; J.L., D.Z. and L.S. collected the date; J.L. and D.Z. wrote the main manuscript text and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Herbst R. S., Heymach J. V. & Lippman S. M. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med 359, 1367–1380 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Statin use and risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. PloS one 8, e77950 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Hao X., Zhang W., Wei Q. & Chen K. The hOGG1 Ser326Cys polymorphism and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 17, 1739–1745 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. et al. The SNP rs402710 in 5p15.33 is associated with lung cancer risk: a replication study in Chinese population and a meta-analysis. PloS one 8, e76252 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. H. et al. Exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and lung cancer by histological type: A pooled analysis of the International Lung Cancer Consortium (ILCCO). Int J Cancer: 10.1002/ijc.28835. (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druesne-Pecollo N. et al. Alcohol drinking and second primary cancer risk in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23, 324–331 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norat T. et al. Fruits and vegetables: updating the epidemiologic evidence for the WCRF/AICR lifestyle recommendations for cancer prevention. Cancer Treat Res 159, 35–50 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaniel M. T., Gardner M. P., Martin R. M. & Jeffreys M. The association of vitamin D supplementation with the risk of cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Causes Control 25, 267–271 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T. Y. et al. Vitamin D intake and lung cancer risk in the Women's Health Initiative. The Am J Clin Nutr 98, 1002–1011 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi R., Faramarzi E., Seyedrezazadeh E., Mohammad-Zadeh M. & Pourmoghaddam M. Evaluation of oxidative stress, antioxidant status and serum vitamin C levels in cancer patients. Biol Trace Elem Res 130, 1–6 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak S. K. et al. Oxidative stress and cyclooxygenase activity in prostate carcinogenesis: targets for chemopreventive strategies. Eur J Cancer 41, 61–70 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7, 177–188 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J. & Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 327, 557–560 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. & Thompson S. G. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta-regression. Stat Med 23, 1663–1682 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsopoulos N. A., Evangelou E. & Ioannidis J. P. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol 37, 1148–1157 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C. B. & Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M. & Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj 315, 629–634 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias A. Assessing the in fluence of a single study in the meta-analysis estimate. Stata Tech Bull 47, 15–17 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. & Longnecker M. P. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 135, 1301–1309 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini N. & Bellocco R. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata J 6, 40–57 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Larsson S. C., Giovannucci E. & Wolk A. Folate and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 99, 64–76 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. M. et al. Black and green tea consumption and the risk of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 93, 506–515 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Kang S. & Zhang D. Association of vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and methionine with risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 109, 1926–1944 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Tian C. & Zhang X. Dietary calcium intake, vitamin D levels, and breast cancer risk: a dose-response analysis of observational studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 136, 309–312 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell F. E. Jr, Lee K. L. & Pollock B. G. Regression models in clinical studies: determining relationships between predictors and response. J Natl Cancer Inst 80, 1198–1202 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandera E. V. et al. Diet and alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in the New York State Cohort (United States). Cancer Causes Control 8, 828–840 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelora E. C., Stockwell H. G., Armstrong A. W. & Pinkham P. A. Dietary intake and risk of lung cancer in women who never smoked. Nutr Cancer 17, 263–270 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feskanich D. et al. Prospective study of fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of lung cancer among men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst 92, 1812–1823 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontham E. T. et al. Dietary vitamins A and C and lung cancer risk in Louisiana. Cancer 62, 2267–2273 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaziano J. M. et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301, 52–62 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Burch J. D., Howe G. R., Risch H. A. & Miller A. B. Dietary factors and risk of lung cancer: results from a case-control study, Toronto, 1981–1985. Int J Cancer 45, 287–293 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds M. W., Kolonel L. N., Hankin J. H. & Lee J. Dietary vitamin A, carotene, vitamin C and risk of lung cancer in Hawaii. Am J Epidemiol 119, 227–237 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Marchand L., Yoshizawa C. N., Kolonel L. N., Hankin J. H. & Goodman M. T. Vegetable consumption and lung cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in Hawaii. J Natl Cancer Inst 81, 1158–1164 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhouser M. L. et al. Fruits and vegetables are associated with lower lung cancer risk only in the placebo arm of the beta-carotene and retinol efficacy trial (CARET). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12, 350–358 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocke M. C., Bueno-de-Mesquita H. B., Feskens E. J., van Staveren W. A. & Kromhout D. Repeated measurements of vegetables, fruits, beta-carotene, and vitamins C and E in relation to lung cancer. The Zutphen Study. Am J Epidemiol 145, 358–365 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatore C. G., Littman A. J., Au D. H., Satia J. A. & White E. Long-term use of supplemental multivitamins, vitamin C, vitamin E, and folate does not reduce the risk of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177, 524–530 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer F. E., Colditz G. A., Hunter D. J., Rosner B. & Hennekens C. Prospective study of smoking, antioxidant intake, and lung cancer in middle-aged women (USA). Cancer Causes Control 10, 475–482 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani E. D. et al. Dietary antioxidants and lung cancer risk: a case-control study in Uruguay. Nutr Cancer 34, 100–110 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz K. A., Potter J. D. & Folsom A. R. Vegetables, fruit, and lung cancer in the Iowa Women's Health Study. Cancer Res 53, 536–543 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata Y. et al. Intakes of fruits, vegetables, and related vitamins and lung cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Men's Health Study (2002–2009). Nutr Cancer 65, 51–61 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorrips L. E. et al. A prospective cohort study on antioxidant and folate intake and male lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9, 357–365 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong L. C. et al. Intake of vitamins E, C, and A and risk of lung cancer. The NHANES I epidemiologic followup study. First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 146, 231–243 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. M., Stram D. O., Arakawa K., Lee H. P. & Yu M. C. Dietary cryptoxanthin and reduced risk of lung cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12, 890–898 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R. A. et al. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 11, 85–95 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sram R. J. et al. Vitamin C for DNA damage prevention. Mutat Res 733, 39–49 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traber M. G. et al. Vitamins C and E: beneficial effects from a mechanistic perspective. Free Radic Biol Med 51, 1000–1013 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. et al. Dietary intake of vitamins A, C, and E and the risk of colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev 22, 529–539 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T. K. et al. Prediagnostic plasma vitamin C and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. Am J Clin Nutr 98, 1289–1297 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulan H. et al. Retinol, vitamins A, C, and E and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Cancer Causes Control 22, 1383–1396 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandera E. V., Gifkins D. M., Moore D. F., McCullough M. L. & Kushi L. H. Antioxidant vitamins and the risk of endometrial cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 20, 699–711 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo M. R. & Flint J. Meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Trends Genet 20, 439–444 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]