Abstract

Objectives

Different accelerometer cutpoints used by different researchers often yields vastly different estimates of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA). This is recognized as cutpoint non-equivalence (CNE), which reduces the ability to accurately compare youth MVPA across studies. The objective of this research is to develop a cutpoint conversion system that standardizes minutes of MVPA for six different sets of published cutpoints.

Design

Secondary data analysis

Methods

Data from the International Children’s Accelerometer Database (ICAD; Spring 2014) consisting of 43,112 Actigraph accelerometer data files from 21 worldwide studies (children 3-18 years, 61.5% female) were used to develop prediction equations for six sets of published cutpoints. Linear and non-linear modeling, using a leave one out cross-validation technique, was employed to develop equations to convert MVPA from one set of cutpoints into another. Bland Altman plots illustrate the agreement between actual MVPA and predicted MVPA values.

Results

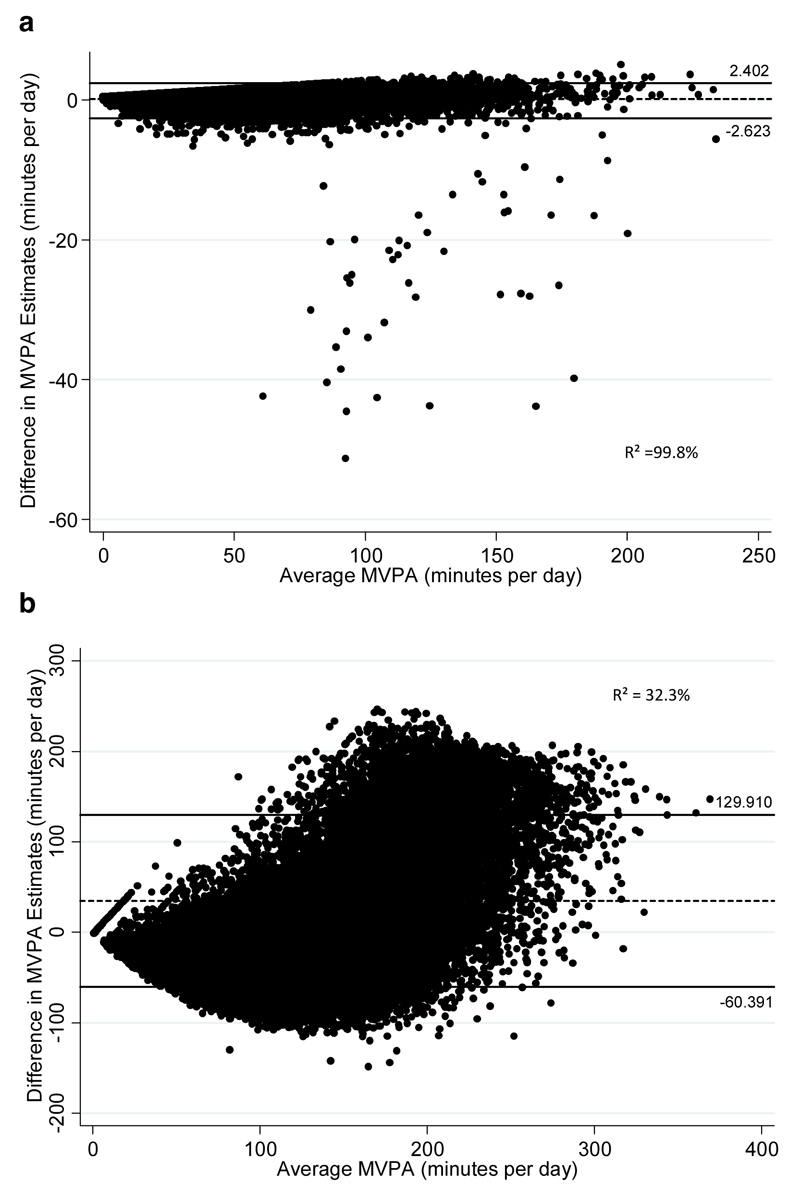

Across the total sample, mean MVPA ranged from 29.7 MVPA min.d-1 (Puyau) to 126.1 MVPA min.d-1 (Freedson 3 METs). Across conversion equations, median absolute percent error was 12.6% (range: 1.3 to 30.1) and the proportion of variance explained ranged from 66.7% to 99.8%. Mean difference for the best performing prediction equation (VC from EV) was -0.110 min.d-1 (limits of agreement (LOA), -2.623 to 2.402). The mean difference for the worst performing prediction equation (FR3 from PY) was 34.76 min.d-1 (LOA, -60.392 to 129.910).

Conclusions

For six different sets of published cutpoints, the use of this equating system can assist individuals attempting to synthesize the growing body of literature on Actigraph, accelerometry-derived MVPA.

Keywords: cutpoints, MVPA, measurement, policy, public health, children

Introduction

Accelerometers are widely used for assessing free living physical activity levels of children and adolescents 1–3. The data typically derived from accelerometers, activity counts, are most commonly processed using a set of calibrated and cross-validated cutpoints 1, 4. The use of cutpoints allows for the data to be distilled into categories of intensity ranging from sedentary to vigorous intensity, with these commonly reported as minutes per day (min⋅d-1) 5. Over the past decade, different sets of cutpoints have been developed for use in studies investigating the activity levels of youth (<18yrs)6–8. Thus, even when raw accelerometer count data between or among studies are very similar, the application of different cutpoints for estimating minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) to those raw data offer vastly different estimates of MVPA 9. Unfortunately, even though studies report physical activity in minutes per day, direct comparison cannot be made across studies employing different sets of cutpoints.

Put simply, activity intensity estimates can differ greatly between studies investigating the same population solely because of the cutpoints chosen by the researchers 10, 11. Bornstein et al., (2011) defined this problem as ‘cutpoint non-equivalence’ (CNE) 12. The overarching limitation inherent in CNE is that direct comparisons across studies measuring physical activity via accelerometry cannot be made since the outcome metric (min⋅d-1) is not equivalent, even though expressed in the same units. Thus, attempts at synthesizing a body of literature, disregarding CNE, leads to distorted and biased conclusions (e.g., combining studies using overly conservative cutpoints with studies using overly generous cutpoints). An example of this issue can be found in the recent Institute of Medicine report “Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies” where physical activity recommendations were made for preschool-age children by evaluating studies that provide different estimates of physical activity based on different cutpoints 13. This scenario substantially impacts the soundness of public health policies and initiatives.

A solution to CNE has been proposed by Bornstein et al. (2011) who employed secondary data to devise a conversion system to translate reported MVPA estimates from one set of cutpoints into another 12. Within the findings, originally disparate estimates of MVPA were able to be compared by using a conversion equation. For instance, comparing three studies that used three different sets of cutpoints reporting 91.2 min⋅d-1, 55.2 min⋅d-1, and 20.8 min⋅d-1 of MVPA was problematic. But after applying the conversion equations the estimates were similar, 59.2 min⋅d-1, 55.2 min⋅d-1, and 58.0 min⋅d-1 of MVPA 12, and, therefore, logical evaluations could be drawn on daily MVPA between the three studies. Converting activity estimates into the same set of cutpoints for evaluation purposes allows practitioners, policy-makers, and researchers to interpret the abundance of evidence on physical activity levels of populations from a common standpoint.

Currently, there are no universally accepted cutpoints, and with the different methodological approaches to calibration studies 14, 15, discrepancies in MVPA estimates between studies (i.e. CNE) will continue. Bornstein et al. (2011) provided a solution to CNE for preschool aged children, therefore, the purpose of this study is to illustrate the use of a conversion system that will translate MVPA (min⋅d-1) produced by one set of cutpoints to an MVPA (min⋅d-1) estimate using a different set of cutpoints for children and adolescents.

Methods

This is a secondary data analysis using existing pooled data from the International Children’s Accelerometer Database (ICAD, http://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/research/studies/icad/; Spring 2014). This database was constructed to gather data on objectively measured physical activity of youth from around the world 16, 17. All individual studies went through their own ethics committee approval. The aims, design, study selection, inclusion criteria, and methods of the ICAD project have been described in detail elsewhere 17. In short, a PubMed search and personal contacts resulted in 24 studies worldwide being approached and invited to contribute data. Inclusion criteria consisted of studies that used a version of the Actigraph accelerometer (Actigraph LLC, Pensacola, FL) in children 3-18 years with a sample size greater than 400 17. After identification, the principal investigator was contacted, and upon agreement, formal data-sharing arrangements were established. All partners (i.e. contributors of data) consulted with their respective research boards to obtain consent before contributing their data to the ICAD. In total, 21 studies conducted between 1998 and 2009 from 10 countries contributed data to the ICAD. The majority of the studies were located in Europe (N=14), with the United States, Brazil, and Australia contributing 4 studies, 1 study, and 2 studies, respectively 17. All individual data within the pooled data set were allocated a unique and non-identifiable participant ID to ensure anonymity of data.

For the present analysis, data from all 21 studies on children and adolescents aged between 3-18 years were used. These data are comprised of 44,454 viable baseline and repeated measures files from a total of 31,976 participants (female 62.4%). A comprehensive description of the assessment of physical activity is available elsewhere 17. Across all studies, Actigraph accelerometers were waist-mounted 17, and all children with a minimum of 1 day, with at least 500 minutes of measured accelerometer wear time were included. The ICAD database epochs varied from 5 seconds to 60 seconds, therefore reintegrated 60-second epochs formed the pooled ICAD database 17. Although the reintegration procedure may slightly over or underestimate MVPA 18, it is commonly accepted when handling different epoch lengths 19, 20.

In an effort to provide researchers with physical activity data derived from a range of Actigraph cutpoints, the ICAD distilled intensity categories (e.g. sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous) from six commonly used Actigraph cutpoints 17, 21. After receiving the ICAD dataset, a MVPA variable was created for each of the six cutpoints. A breakdown of these cutpoints, along with their corresponding MVPA counts-per-minute can be found in Table 1. The cutpoints used by ICAD, and for analysis in this study, were Pate et al. (PT) 7, Puyau et al. (PY) 8, Freedson equation et al., where the MVPA threshold can be either 3 METs (FR3) or 4 METs (FR4) 22–24, Van Cauwenberghe et al. (VC) 25, and Evenson et al. (EV) 26.

Table 1.

Accelerometer cutpoints associated with moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in children and adolescents aged 3-18 years.

| MVPA Cutpoint | Symbol | Age (yrs.) | Meanᵃ | SD | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||||

| Pate et al. | PT | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 1680 | 77.5 | 38.5 |

| Puyau et al. | PY | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 3201 | 29.7 | 21.4 |

| Freedson et al. (3 METS) | FR3 | 369 | 446 | 527 | 614 | 706 | 803 | 906 | 1017 | 1136 | 1263 | 1400 | 1547 | 1706 | 1880 | 2068 | 2274 | 126.1 | 75.8 |

| Freedson et al. (4 METS) | FR4 | 1090 | 1187 | 1290 | 1400 | 1515 | 1638 | 1770 | 1910 | 2059 | 2220 | 2392 | 2580 | 2781 | 3000 | 3239 | 3499 | 64.9 | 47 |

| Van Cauwenberghe et al. | VC | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 2340 | 47.8 | 28.5 |

| Evenson et al. | EV | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 2296 | 49.4 | 29.2 |

Note: All cut-points are presented as counts per minute (CPM).

MVPA minutes per day (N = 43,112)

The development and validation of the prediction equations followed a similar procedure previously used by Bornstein et al. (2011) 12. Linear and non-linear regression models, accounting for valid days and repeated measures on a single participant (i.e. longitudinal data) were used to develop the conversion equations. Due to the nature of the dataset, access to raw accelerometer count data were not available. However, an additional analysis was run to explore if any fixed effects existed between studies that collected data using 60 second epochs (n=14), and studies employing shorter epochs (E.g. 5-30 second epochs, n=7). A ‘leave one out’ cross-validation procedure was employed to assess how well each equation performed 27. In this procedure, each study assumed the role of the validation sample and the remaining 20 studies were used as the derivation sample. This procedure was repeated 21 times until each study had served as the validation sample.

The development of the prediction equations included linear and non-linear terms where appropriate. Furthermore, key covariates were incorporated into the equations where these added significantly to the model including: age (years); gender; and wear time (average wear time per day in minutes). Inclusion criteria for these variables were contingent upon a significant increase in the proportion of variance explained (R2), and a reduction in the average error and absolute percent error. Average error (a) and absolute percent error (b) were calculated using the following formulae:

Above, “Y” is the actual MVPA value and “Yprime” is the predicted MVPA value from the generated equation 12. All equations containing significant demographic variables (e.g. age, gender, wear time) were reported. Finally, Bland Altman plots 28 were used to illustrate the agreement between the actual MVPA value and the predicted MVPA values. Limits of agreement were calculated as [ ṁ ± (2 x ṡ) ] where “ṁ” is the mean difference between the actual and predicted MVPA, and “ṡ” is the mean standard deviation 28. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (v.12.1, College Station, TX).

Results

The final ICAD sample consisted of 43,112 files, representing 31,113 children (female 61.5%) between the ages of 3-18 years. Table 1 displays the average MVPA in minutes per day (min.d-1) for the six sets of cutpoints for the entire sample. Across the six cutpoints, MVPA estimates were from PY 29.65 min.d-1 (± 21.38), VC 47.81 min.d-1 (± 28.52), EV 49.38 min.d-1 (± 29.17), FR4 64.87 min.d-1 (± 47.02), PT 77.55 min.d-1 (± 38.49), and FR3 126.12 min d-1 (± 75.82). Prediction models with the corresponding proportion of variance explained, average error, and absolute percent error are displayed in Table 2. In total, 61 prediction equations were generated. With the exception of two of these equations (VC from EV, and EV from VC), age contributed significantly to the models, while gender was included in three models (VC from FR3, EV from FR3, and PY from FR3). The third covariate under consideration, wear time, did not contribute significantly to any of the models. Additionally, there were no fixed effects between studies that originally used 60 second epochs, and those studies collecting data in shorter epochs, therefore, this was not considered further in any of the models. Using the best model from each possible conversion, the mean absolute percent error was 12.6%, with 1.3% and 30.1% representing the minimum (VC from EV) and maximum (PY from FR3) percent error, respectively. The proportion of variance explained ranged from 66.7% (FR3 from PY) to 99.8% (VC from EV). Figures 1 (a) and (b) illustrates the best (VC from EV) and the worst (FR3 from PY) prediction equations in the form of Bland Altman plots. The mean difference for VC from EV was -0.110 min.d-1, with -2.623 to 2.402 representing the lower and upper bounds of the limits of agreement (LOA), respectively. The mean difference for FR3 from PY was 34.76 min.d-1 (LOA -60.392 to 129.910).

Table 2.

Prediction equations to transform estimates of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA; min.d-1) from one set of cutpoints into MVPA (min.d-1) estimated from another set of cutpoints

| Accelerometer cutpoint MVPA min.d-1 | Prediction Equations ᶧ | Demographics | Leave One Out Cross Validation* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable ᵃ | Predictor Variable | Intercept | MVPA (min.d-1) |

MVPA (min.d-1) Squared |

MVPA (min.d-1) Square root |

Age (years) |

Genderᵇ | Adjusted R2 |

Average Error (min/day) ᶜ |

Absolute % Error ᵈ |

| Freedson (4 MET) | Van Cauwenberghe | -4.5855 | 1.7206 | -0.0026 | 0.611 | 34.68 | 30.9 | |||

| Van Cauwenberghe | 118.5514 | 1.0465 | 0.0004 | -9.0859 | 0.931 | 15.18 | 13.0 | |||

| Evenson | -2.9598 | 1.4872 | -0.0017 | 0.618 | 34.30 | 30.6 | ||||

| Evenson | 117.2174 | 1.0222 | 0.0004 | -9.0203 | 0.933 | 14.97 | 12.8 | |||

| Pate | -15.8486 | 1.0409 | 0.726 | 29.15 | 25.5 | |||||

| Pate | 112.5384 | 1.0780 | 0.0003 | -5.2759 | -7.7031 | 0.945 | 13.43 | 12.3 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -10.0605 | 0.4168 | 0.0002 | 1.4270 | 0.904 | 15.94 | 14.9 | |||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -57.4086 | 0.5821 | 0.0002 | 0.3919 | 3.3287 | 0.921 | 15.06 | 13.6 | ||

| Puyau | -6.5762 | 0.7572 | -0.0009 | 9.8330 | 0.498 | 39.82 | 36.3 | |||

| Puyau | 133.2262 | 1.3785 | -0.0015 | 1.5535 | -9.9722 | 0.894 | 18.81 | 16.3 | ||

| Van Cauwenberghe | Freedson (4 MET) | -10.6973 | 0.0346 | -0.0001 | 7.5217 | 0.640 | 20.88 | 24.7 | ||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -112.7420 | 0.6121 | -0.0009 | 5.8395 | 7.1432 | 0.916 | 10.35 | 11.5 | ||

| Evenson | -0.4432 | 0.9772 | 0.998 | 1.28 | 1.3 | |||||

| Pate | 3.0936 | 0.8355 | 0.0001 | -2.4403 | 0.937 | 8.07 | 11.1 | |||

| Pate | -11.4262 | 0.9492 | -0.0002 | -3.1015 | 1.1471 | 0.950 | 7.01 | 9.9 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -17.4535 | 0.2050 | -0.0005 | 4.7324 | 0.467 | 24.43 | 30.9 | |||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -148.3597 | 0.6616 | -0.0007 | 1.8747 | 9.2024 | 0.778 | 15.73 | 20.3 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -142.2791 | 0.5771 | -0.0006 | 2.6592 | 8.9591 | -5.2698 | 0.785 | 15.49 | 19.9 | |

| Puyau | 0.2787 | 1.1261 | -0.0011 | 3.0543 | 0.946 | 7.31 | 10.0 | |||

| Puyau | 11.4445 | 1.1768 | -0.0011 | 2.3872 | -0.7958 | 0.953 | 6.74 | 9.2 | ||

| Evenson | Pate | -7.6013 | 0.7347 | 0.941 | 8.05 | 10.6 | ||||

| Pate | -22.9695 | 0.7633 | 1.1398 | 0.953 | 6.87 | 9.4 | ||||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -17.7246 | 0.2088 | -0.0005 | 4.8722 | 0.475 | 24.86 | 30.3 | |||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -151.3777 | 0.6753 | -0.0007 | 1.9502 | 9.3962 | 0.785 | 15.89 | 19.7 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -145.2212 | 0.5898 | -0.0006 | 2.7444 | 9.1499 | -5.3351 | 0.792 | 15.64 | 19.2 | |

| Van Cauwenberghe | 0.5413 | 1.0215 | 0.998 | 1.31 | 1.3 | |||||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -10.6026 | 0.0329 | 0.0000 | 7.7146 | 0.647 | 21.18 | 24.1 | |||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -114.2384 | 0.6204 | -0.0009 | 5.9992 | 7.2554 | 0.919 | 10.39 | 11.2 | ||

| Puyau | -0.0162 | 1.0679 | -0.0007 | 3.6674 | 0.942 | 7.77 | 10.4 | |||

| Puyau | 12.2396 | 1.1234 | -0.0008 | 2.9359 | -0.8736 | 0.950 | 7.13 | 9.1 | ||

| Pate | Freedson (3 MET) | -19.5240 | 0.2505 | -0.0006 | 7.2571 | 0.616 | 28.65 | 21.2 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -181.2504 | 0.8145 | -0.0008 | 3.7267 | 11.3690 | 0.880 | 16.40 | 11.3 | ||

| Van Cauwenberghe | 15.1517 | 1.3052 | 0.935 | 11.27 | 9.6 | |||||

| Van Cauwenberghe | 36.4870 | 1.2695 | -1.7003 | 0.952 | 9.41 | 8.2 | ||||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -5.3433 | 0.0244 | 0.0002 | 10.6224 | 0.754 | 23.44 | 17.4 | |||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -116.4227 | 0.6531 | -0.0007 | 8.7913 | 7.7757 | 0.934 | 11.67 | 9.2 | ||

| Evenson | 14.3381 | 1.2802 | 0.941 | 10.80 | 9.2 | |||||

| Evenson | 34.7490 | 1.2459 | -1.6215 | 0.956 | 9.02 | 7.7 | ||||

| Puyau | 3.7073 | 0.8087 | -0.0007 | 9.9610 | 0.817 | 18.79 | 16.0 | |||

| Puyau | 41.4428 | 0.9799 | -0.0009 | 7.7065 | -2.6895 | 0.860 | 16.05 | 13.9 | ||

| Freedson (3 MET) | Van Cauwenberghe | -8.7703 | 1.0464 | -0.0025 | 14.1213 | 0.430 | 68.67 | 33.3 | ||

| Van Cauwenberghe | 247.3136 | 0.6734 | 0.0005 | 8.9683 | -18.3805 | 0.908 | 27.39 | 13.7 | ||

| Freedson (4 MET) | 12.5470 | 2.0066 | -0.0022 | 0.910 | 26.89 | 13.0 | ||||

| Freedson (4 MET) | 120.4882 | 1.5802 | -0.0017 | -7.2474 | 0.950 | 19.98 | 9.9 | |||

| Evenson | 22.1710 | 2.5511 | -0.0065 | 0.436 | 68.31 | 33.1 | ||||

| Evenson | 266.2679 | 1.6217 | -0.0021 | -18.3044 | 0.910 | 27.26 | 13.5 | |||

| Pate | 10.3366 | 1.5058 | 0.566 | 59.91 | 28.0 | |||||

| Pate | 233.2335 | 1.1204 | -16.6202 | 0.940 | 22.86 | 10.3 | ||||

| Puyau | 1.1251 | -0.5376 | 0.0011 | 27.3953 | 0.3234 | 74.95 | 37.2 | |||

| Puyau | 273.8841 | 0.6415 | -0.0001 | 11.7666 | -19.4780 | 0.8735 | 31.42 | 16.3 | ||

| Puyau | Pate | -8.8032 | 0.4958 | 0.799 | 10.66 | 23.2 | ||||

| Pate | -27.3259 | 0.5302 | 1.3738 | 0.833 | 9.50 | 21.2 | ||||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -2.0648 | 0.3641 | -0.0007 | 0.343 | 19.80 | 41.5 | ||||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -109.0616 | 0.5579 | -0.0006 | 6.9629 | 0.659 | 14.00 | 30.7 | |||

| Freedson (3 MET) | -101.9867 | 0.5345 | -0.0006 | 6.7734 | -4.1982 | 0.667 | 13.85 | 30.1 | ||

| Van Cauwenberghe | -2.4459 | 0.6144 | 0.0009 | 0.943 | 5.61 | 11.8 | ||||

| Van Cauwenberghe | -9.8824 | 0.6432 | 0.0007 | 0.5610 | 0.949 | 5.25 | 11.1 | |||

| Freedson (4 MET) | 3.2866 | 0.5067 | -0.0010 | 0.510 | 17.86 | 34.7 | ||||

| Freedson (4 MET) | -82.9904 | 0.8491 | -0.0014 | 5.7854 | 0.832 | 10.55 | 20.4 | |||

| Evenson | -2.5646 | 0.5941 | 0.0009 | 0.939 | 5.80 | 12.4 | ||||

| Evenson | -10.5480 | 0.6249 | 0.0007 | 0.5994 | 0.946 | 5.40 | 11.7 | |||

Key:

Prediction equations developed using entire sample (n = 43112)

For example, predicting Freedson (4MET) MVPA min.d-1 using Van Cauwenberghe cutpoints

1 = males, 0 = Females

Average Error calculated using formula: √ [Σ(Y - Y')2 / (N - 1)] where Y is the actual value and Y' is the predicted value

Absolute Percent Error calculated using formula: [(Y - Y')/Y] x 100

One study used as validation, 20 studies as derivation. Repeated until each study served as validation.

Figure 1.

Bland Altman plots of best (a) and worst (b) agreement between actual MVPA and predicted MVPA values.

(a) Van Cauwenberghe MVPA predicted from Evenson MVPA. Dashed line signifies mean difference (-0.110 min.d-1).

(b) Freedson (3MET) MVPA predicted from Puyau MVPA (Age not in model). Dashed line signifies mean difference (34.76 min.d-1)

Discussion

The use of accelerometers provides researchers with a practical, reliable, and valid tool to objectively measure physical activity levels of children and adolescents. Despite these benefits, the widespread use of accelerometers in the field of physical activity measurement has continued to be burdened by CNE4, 11, 29. The use of different cutpoints has resulted in contrasting estimates of physical activity for children and adolescents, thereby, significantly limiting comparisons of the estimates of physical activity intensity and the prevalence of meeting physical activity guidelines9, 15, 29.

This study has built on the concept of cutpoint conversion first demonstrated by Bornstein et al. (2011) for preschool-aged children, and provides a solution to the problem of CNE for children and adolescents aged 3-to-18 years. Table 3 (supplementary table) demonstrates the utility and accuracy of this equating system by using previous research that has published MVPA estimates (min.d-1) on two or more cutpoints coinciding with the cutpoints used in this study 10, 25, 29. Recognizing the problem of CNE, Guinhouya et al. examined MVPA of children aged 9 years using FR3 and PY cutpoints 10. Of concern, was the difference in the estimate of MVPA between the two sets of cutpoints (113 MVPA min.d-1) 10. Using the specific conversion equation developed herein for these two cutpoints, the difference is reduced to 7 MVPA min.d-1. In comparison, converting FR3 MVPA in to PY MVPA has taken MVPA estimates from uninformative (141 MVPA min.d-1 vs. 28 MVPA min.d-1) 10, to coherence ( 21 MVPA min.d-1 vs. 28 MVPA min.d-1). It must be noted that a degree of heteroscedasticity can be observed in Figure 1b, where the proportion of variance explained was low (>33%). Rosetta Stone users must interpret their MVPA predictions with caution when using some of the ‘poorer performing’ prediction equations (R2 = <60%). Ultimately, these conversion equations present a practical solution to synthesizing the growing body of literature that reports estimates of youth MVPA using accelerometers to guide public health policy for children and adolescent physical activity recommendations.

A major strength of this study is the diversity and sample size of the data used to derive the conversion equations. The ICAD sample consisted of information on over 30,000 children and adolescents, from 10 different countries, representing 21 studies using waist-mounted Actigraph accelerometers 17. Although the conversion equations are limited to the six cutpoints used for this study, the cutpoints employed herein are commonly used within the physical activity literature 21, therefore providing widespread utility of the prediction equations for future research to evaluate their findings. Lastly, the equating system is relatively simple to use and requires commonly published and accessible information (e.g. MVPA min.d-1, age, gender).

On the other hand, there are limitations to this study that need to be considered. As mentioned previously, the original cutpoints provided by ICAD do not represent the entire range of cutpoints available for use in the field (e.g. Treuth30, Mattocks22 ), however, future iterations of the Rosetta Stone should look to include new prediction equations developed on different cutpoints than those employed in this study. It must be noted that the cutpoints employed in this analysis were developed with some amount of error, and the prediction equations generated within this study bring an additional degree of error. However, while this error exists, one must consider what is worse - comparing estimates of MVPA that indicate a difference of over 100 min⋅d-1 between cut points or 7 min⋅d-1? Also, the 21 studies forming the ICAD database reported epochs ranging from 5 seconds to 60 seconds. The ICAD database reintegrated seven of the 21 studies into 60 second epochs 17, and research has shown how MVPA data collected in shorter epochs (e.g. 5 seconds) can result in higher estimates of MVPA compared to MVPA data collected in longer epochs 18. Although an additional analysis confirmed no fixed effects existed between studies that collected data using 60 second epochs and studies employing shorter epochs, the impact the reintegration procedure may hold over conversion equations is still unknown. Further investigation is required into the degree of error surrounding the formation of prediction equations from different epoch lengths, and how that may compromise the generalizability of the conversions.

Conclusion

In summary, this study proposes a solution to CNE by illustrating the use of an equating system that demonstrates acceptable accuracy allowing for comparisons across six different sets of cutpoints used for measuring MVPA in children and adolescents. Until a universally accepted cutpoint can be agreed, researchers will continue to select different cutpoints, and disparities will continue among studies evaluating physical activity levels of similar populations. This considerably impedes efforts to synthesize the growing body of literature on children and adolescents physical activity behavior. Utilizing the equating system gives researchers, practitioners and policymakers the capacity to “paint a better picture” of physical activity levels through which relevant policies can be developed and evaluated.

Supplementary Material

Practical Implications.

-

-

The prediction equations developed within this study allow practitioners to synthesize accelerometer-derived MVPA estimates of children and adolescents between the ages of 3 and 18 years across six commonly used Actigraph cutpoints.

-

-

Converting accelerometer-derived MVPA estimates into the same set of cutpoints for evaluation purposes allows practitioners, policy-makers, and researchers to interpret the abundance of evidence on physical activity levels of populations (e.g. youth of different ages) from a common standpoint.

-

-

With a coherent understanding of the population prevalence of physical activity, policy-makers can evaluate, and potentially reconsider, the realism of policies and standards pertaining to children and adolescents physical activity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants of the original studies that contributed data to ICAD. No financial assistance was provided for the secondary data analysis of this project. The pooling of the data was funded through a grant from the National Prevention Research Initiative (Grant Number: G0701877) (http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Ourresearch/Resourceservices/NPRI/index.htm). The funding partners relevant to this award are: British Heart Foundation; Cancer Research UK; Department of Health; Diabetes UK; Economic and Social Research Council; Medical Research Council; Research and Development Office for the Northern Ireland Health and Social Services; Chief Scientist Office; Scottish Executive Health Department; The Stroke Association; Welsh Assembly Government and World Cancer Research Fund. This work was additionally supported by the Medical Research Council [MC_UU_12015/3; MC_UU_12015/7], Bristol University, Lougborough University and Norwegian School of Sport Sciences. We also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Professor Chris Riddoch, Professor Ken Judge and Dr Pippa Griew to the development of ICAD. Jo Salmon is supported by an Australian National Health & Medical Research Council Principal Research Fellowship (APP1026216); Anna Timperio is supported by a National Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (Award ID 100046).

Footnotes

ICAD Collaborators

The ICAD Collaborators include: Prof LB Andersen, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark (Copenhagen School Child Intervention Study (CoSCIS)); Prof S Anderssen, Norwegian School for Sport Science, Oslo, Norway (European Youth Heart Study (EYHS), Norway); Prof G Cardon, Department of Movement and Sports Sciences, Ghent University, Belgium (Belgium Pre-School Study); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Hyattsville, MD USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)); Prof A Cooper, Centre for Exercise, Nutrition and Health Sciences, University of Bristol, UK (Personal and Environmental Associations with Children's Health (PEACH)); Dr R Davey, Centre for Research and Action in Public Health, University of Canberra, Australia (Children’s Health and Activity Monitoring for Schools (CHAMPS)); Prof U Ekelund, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, Norway & MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, UK; Dr DW Esliger, School of Sports, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, UK; Dr K Froberg, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark (European Youth Heart Study (EYHS), Denmark); Dr P Hallal, Postgraduate Program in Epidemiology, Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil (1993 Pelotas Birth Cohort); Prof KF Janz, Department of Health and Human Physiology, Department of Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, US (Iowa Bone Development Study); Dr K Kordas, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, UK (Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)); Dr S Kriemler, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Zürich, Switzerland (Kinder-Sportstudie (KISS)); Dr A Page, Centre for Exercise, Nutrition and Health Sciences, University of Bristol, UK; Prof R Pate, Department of Exercise Science, University of South Carolina, Columbia, US (Physical Activity in Pre-school Children (CHAMPS-US) and Project Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (Project TAAG)); Dr JJ Puder, Service of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, University of Lausanne, Switzerland (Ballabeina Study); Prof J Reilly, Physical Activity for Health Group, School of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK (Movement and Activity Glasgow Intervention in Children (MAGIC)); Prof. J Salmon, Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia (Children Living in Active Neigbourhoods (CLAN)); Prof LB Sardinha, Exercise and Health Laboratory, Faculty of Human Movement, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal (European Youth Heart Study (EYHS), Portugal); Dr LB Sherar, School of Sports, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, UK; Dr A Timperio, Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research, Deakin University Melbourne, Australia (Healthy Eating and Play Study (HEAPS)); Dr EMF van Sluijs, MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, UK (Sport, Physical activity and Eating behaviour: Environmental Determinants in Young people (SPEEDY)).

References

- 1.Reilly JJ, Penpraze V, Hislop J, et al. Objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviour: review with new data. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(7):614–619. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.133272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cliff DP, Okely AD. Comparison of two sets of accelerometer cut-off points for calculating moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in young children. J Phys Act Health. 2007;4(4):509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S531–543. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Beets MW, Welk GJ. Everything you wanted to know about selecting the “right” Actigraph accelerometer cut-points for youth, but…: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15(4):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trost SG. State of the art reviews: measurement of physical activity in children and adolescents. AM J Lifestyle Med. 2007;1(4):299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pate RR, Almeida MJ, McIver KL, et al. Validation and calibration of an accelerometer in preschool children. Obesity. 2006;14(11):2000–2006. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, et al. Validation and calibration of physical activity monitors in children. Obes Res. 2002;10(3):150–157. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beets MW, Bornstein D, Dowda M, et al. Compliance with national guidelines for physical activity in US preschoolers: measurement and interpretation. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):658–664. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guinhouya CB, Hubert H, Soubrier S, et al. Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity among Children: Discrepancies in Accelerometry-Based Cut-off Points. Obesity. 2006;14(5):774–777. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bornstein DB, Beets MW, Byun W, et al. Accelerometer-derived physical activity levels of preschoolers: a meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(6):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bornstein DB, Beets MW, Byun W, et al. Equating accelerometer estimates of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: In search of the Rosetta Stone. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(5):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birch LL, Parker L, Burns A. Early childhood obesity prevention policies. National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Routen AC, Upton D, Edwards MG, et al. Discrepancies in accelerometer-measured physical activity in children due to cut-point non-equivalence and placement site. J Sport Sci. 2012;30(12):1303–1310. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2012.709266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, et al. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43(7):1360–1368. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318206476e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekelund U, Luan Ja, Sherar LB, et al. Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time and cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307(7):704–712. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherar LB, Griew P, Esliger DW, et al. International children's accelerometry database (ICAD): design and methods. BMC public health. 2011;11(1):485. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y, Beets MW, Pate RR, et al. The effect of reintegrating Actigraph accelerometer counts in preschool children: Comparison using different epoch lengths. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;16(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2008;40(4):622–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson A, Ekelund U, Yngve A, et al. Assessing physical activity among children with accelerometers using different time sampling intervals and placements. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2002;14(1):87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, et al. Using accelerometers in youth physical activity studies: a review of methods. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(3):437–450. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattocks C, Leary S, Ness A, et al. Calibration of an accelerometer during free-living activities in children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2(4):218–226. doi: 10.1080/17477160701408809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trost SG, Pate RR, Freedson PS, et al. Using objective physical activity measures with youth: how many days of monitoring are needed? Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2000;32(2):426–431. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedson P, Pober D, Janz K. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S523. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185658.28284.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Cauwenberghe E, Labarque V, Trost SG, et al. Calibration and comparison of accelerometer cut points in preschool children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2-2):e582–e589. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.526223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, et al. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sport Sci. 2008;26(14):1557–1565. doi: 10.1080/02640410802334196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stone M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J R Stat Soc Series B (Methodological) 1974:111–147. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin Bland J, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The lancet. 1986;327(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loprinzi PD, Lee H, Cardinal BJ, et al. The relationship of actigraph accelerometer cut-points for estimating physical activity with selected health outcomes: results from NHANES 2003–06. Res Quart Exercise Sport. 2012;83(3):422–430. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2012.10599877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Treuth MS, Schmitz K, Catellier DJ, et al. Defining accelerometer thresholds for activity intensities in adolescent girls. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2004;36(7):1259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.