Abstract

An immunocompetent health care worker with no known history of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) disease was exposed to a patient with herpes zoster and was immunized 2 days later. Twenty-seven days after receiving the varicella vaccine, while hospitalized, she developed a disseminated rash. This exposure and subsequent development of symptoms posed infection control challenges. A polymerase chain reaction analysis of her vesicular fluid was positive for vaccine-type VZV, and a blood specimen collected before vaccination demonstrated a positive VZV titer by the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen test. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previous reports of an immunocompetent seropositive person developing vaccine-type VZV after receiving the vaccine.

Keywords: Immunocompetent, vaccine, rash, infection control, polymerase chain reaction

Between 5% and 10% of Americans reach adulthood still susceptible to varicella. The disease is often more serious in adults than in children. The varicella vaccine was found to be highly immunogenic in several trials in adults,1,2 and it is recommended for adults without demonstrated immunity.3 However, as reported by Marin et al,4 only 3% of adults with varicella had been vaccinated. It is especially important for health care workers to be immune to protect both themselves and their patients.

Adverse events from the varicella vaccine include vesicular rashes in 6%–8% of healthy, susceptible adults.2 Vesicular rashes due to the vaccine (Oka) strain (vaccine-type varicella-zoster virus [vVZV]) typically occur 14–28 days after vaccination (range, 5 days to 6 weeks).“Breakthrough” varicella (wild-type VZV) is a vesicular rash appearing after exposure to natural varicella in a vaccinated person in whom the vaccine provides only partial protection. Distinguishing between vVZV and wild-type VZV is important, because vVZV rarely causes serious illness and is not highly communicable.

Here we report an unusual case of a vVZV rash in a immunocompetent seropositive health care worker. The rash developed while the health care worker was hospitalized for endocarditis, raising several complex infection control issues.

CASE REPORT

A 60-year-old female registered nurse with a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cared for a patient with a vesicular neck rash that was subsequently diagnosed as herpes zoster. The nurse had no known history of chickenpox, and antibody titers drawn in 2000, 2003, and 2008 were negative by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). She had previously declined immunization with the varicella vaccine.

When informed of her exposure 2 days later, she decided to be immunized. Before immunization, a serum specimen was sent for VZV antibody measurement by the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) test.

Later, while at home, the patient became febrile (103°F), with cough, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. After 3 days, she presented to the emergency department (ED) and was hospitalized with broad differential diagnoses, including a possible adverse reaction to the varicella vaccine. Blood and urine cultures grew Proteus mirabilis, and transthoracic echocardiography revealed a large, mobile vegetation on the mitral valve. She was ultimately diagnosed with P mirabilis urosepsis and endocarditis and underwent valve replacement surgery.

Because of concerns about the possible concurrent development of varicella, the patient was placed on isolation precautions for days 10–21 postexposure. No sign of VZV disease developed during this period. On day 27 postexposure, while still hospitalized, she developed scattered papular and vesicular lesions with erythematous bases on her thighs that subsequently spread to her trunk, back, and arms (12–24 lesions in total). A dermatologist diagnosed varicella.

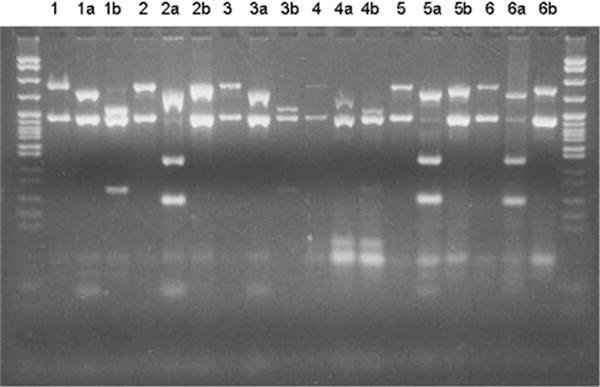

On day 29 postexposure, the patient was again placed on isolation precautions and started on antiviral treatment (valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 10 days). Skin scrapings were performed. A thigh lesion was negative by culture, and a back lesion was negative for VZV by direct immunofluorescence antibody and culture. A fluid specimen from another lesion was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which revealed vVZV5 (Fig 1). At this time, it was discovered that the patient’s FAMA test, performed before vaccination, was positive for VZV antibodies at a titer of 1:4. This test was performed twice on the pre-vaccination specimen to verify the result. This positive serology was considered an accurate indication of previous immunity, given that antibodies in the setting of primary infection are not seen until days after the varicella rash appears. The lesions were fully crusted by day 37 postexposure, and the patient did not develop any complications from vVZV.

Fig 1.

PCR comparing wild-type VZV and vVZV. Lane 5 shows the patient presented in this report.

DNA markers: 622–67 bp.

Lane 1: Uncut wild-type VZV DNA control: 350- and 222-bp bands

1a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band is uncut.

1b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band is digested, resulting in fragments of 250 and 100 bp.

Lane 2: Uncut vVZV DNA control: 350- and 222-bp bands

2a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band digested, resulting in fragments of 135 and 87 bp.

2b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band is uncut.

Lane 3: Uncut amplified DNA from a clinical sample: 350- and 222-bp bands

3a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band is uncut.

3b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band is digested, resulting in fragments of 250 and 100 bp. Interpretation: wVZV

Lane 4: Uncut amplified DNA from a clinical sample: 350- and 222-bp bands

4a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band is uncut.

4b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band is digested, resulting in fragments of 250 and 100 bp. Interpretation: wVZV

Lane 5: Uncut amplified DNA from the patient reported here: 350- and 222-bp bands

5a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band digested, resulting in fragments of 135 and 87 bp.

5b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band is uncut. Interpretation: vVZV

Lane 6: Uncut amplified DNA from a clinical sample: 350- and 222-bp bands

6a: BgL I digestion: The 222-bp band digested, resulting in fragments of 135 and 87 bp

6b: Pst I digestion: The 350-bp band digested, resulting in fragments of 250 and 100 bp. Interpretation: vVZV.

Because it was initially unclear whether the patient had wild-type VZV or vVZV, an extensive exposure workup was performed that identified 21 patient contacts and 49 physician and staff contacts. Once the PCR results were known, the investigation was terminated. There were no subsequently reported contact cases of VZV.

DISCUSSION

vVZV in a seropositive, immunocompetent individual has not been reported previously. There are known cases of secondary transmission of vVZV to persons with a self-reported history of varicella,6 but these are extremely rare. This case also raises several important issues regarding vaccinating health care workers, limitations of commonly used antibody testing methods, adverse events associated with immunization, and infection control issues surrounding VZV exposure in the health care setting.

Compared with children, adults have more severe VZV disease in terms of both clinical presentation and frequency of complications.7 Therefore, organizations including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention3 now recommend the vaccine for susceptible adults. Questioning an individual regarding a previous history of VZV disease is often inadequate, however. As Krasinski et al8 reported, in 6 incidents of hospital exposure to VZV, approximately 30% of patients and staff were unaware of their immune status; when tested, only 10% were susceptible. Laboratory determination of immune status has been recommended for health care workers before varicella vaccination or after exposure to VZV.9

Although testing for immunity is clearly valuable, there are problems with the methods in current use. Antibodies can be detected by either ELISA or latex agglutination, but these tests have their limitations.7 ELISA is the most commonly used assay; however, Saiman et al10 reported only 74% sensitivity and 89% specificity when testing for seroconversion after vaccination. Latex agglutination cannot be automated and does not demonstrate VZV IgM, and the investigator must be certain of the appearance of both the latex agglutination and prozone reactions.11

What is needed is a robust and convenient serologic assay to indicate varicella immunity.7 Although the FAMA can provide this, it is primarily a research test that is not widely available.11 Recently, Sauerbrei and Wutzler12 identified an ELISA that appears to be more sensitive and specific than the commercial ELISA, but more studies are needed. In this case, the chain of events described herein could have been avoided had the health care worker’s immune status been clear from the beginning.

Because VZV is highly communicable to nonimmune persons, all patients with any VZV disease are placed on isolation in our hospital. This patient was twice placed on precautions, during the VZV disease incubation period and later when she developed a varicella-like rash. The latter episode led to an extensive contact investigation, because she was potentially infectious for 1–2 days before the rash appeared and was not isolated for 2 additional days thereafter.

This raises another infection control issue, involving the differentiation between wild-type VZV and vVZV. Our patient was initially considered a candidate for wild-type VZV, although her presentation (small number of lesions; absence of fever, pain, pruritus; and longer incubation period than customary for wild-type disease) was more consistent with vVZV.13,14 PCR can diagnose VZV infection within a few hours without isolating the virus in culture.11 Fortunately, we had access to PCR testing, and once the results were known, the exposure investigation ended, given that contagion from vVZV is extremely rare (1 in 10 million exposures) and the resulting disease is almost always mild (<50 lesions).13,14

CONCLUSIONS

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports of a seropositive immunocompetent patient developing vVZV after receiving the varicella vaccine. This case illustrates the need for a highly sensitive and specific serologic test for immunity to VZV. Moreover, it is best to vaccinate identified nonimmune health care workers promptly instead of waiting until an exposure occurs. When a rash develops after vaccination, PCR is the gold standard for diagnosis and differentiation of wild-type VZV and vVZV.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: A.A.G. lectures and consults for Merck and Co. and GlaxoSmithKline. She receives research funding from Merck. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gershon AA, Steinberg SP, LaRussa P, Ferara A, Hammerschlag M, Gelb L. Immunization of healthy adults with live attenuated varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:132–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy IR, Gershon AA. Prospects for use of a varicella vaccine in adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4:159–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-4):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marin M, Watson T, Chaves S, Civen R, Watson B, Zhang J, et al. Varicella among adults: data from an active surveillance project, 1995–2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:S94–100. doi: 10.1086/522155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaRussa P, Lungu O, Hardy I, Gershon A, Steinberg S, Silverstein S. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of polymerase chain reaction products from vaccine and wild-type varicella-zoster virus isolates. J Virol. 1992;66:1016–20. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1016-1020.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossberg R, Harpaz R, Rubtcova E, Loparev V, Seward J, Schmid D. Secondary transmission of varicella vaccine virus in a chronic care facility for children. J Pediatr. 2006;148:842–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hambleton S, Gershon AA. Preventing varicella-zoster disease. Clin Micro Rev. 2005;18:70–80. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.70-80.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krasinski K, Holzman R, La Couture R, Florman AL. Hospital experience with varicella-zoster virus. Infect Control. 1986;7:312–6. doi: 10.1017/s019594170006433x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher J, Quaid B, Cryan B. Susceptibility to varicella-zoster virus infection in health care workers. Occup Med. 1996;46:289–92. doi: 10.1093/occmed/46.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saiman L, LaRussa P, Steinberg S, Zhou J, Baron K, Whittier S, et al. Persistence of immunity to varicella-zoster virus after vaccination of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:279–83. doi: 10.1086/501900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon A. Varicella-zoster virus: prospects for control. In: Arnoff SC, Hughes WT, Wald ER, Kohl S, Speck WT, editors. Advances in pediatric infectious diseases. Vol. 10. St Louis: Mosby; 1995. pp. 93–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. Serological detection of varicella-zoster virus–specific immunoglobulin G by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using glycoprotein antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3094–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00719-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsolia M, Gershon AA, Steinberg S, Gelb L, NIAID Varicella Vaccine Collaborative Study Group Live attenuated varicella vaccine: evidence that the virus is attenuated and the importance of skin lesions in transmission of varicella-zoster virus. J Pediatr. 1990;116:184–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaRussa P, Steinberg S, Meurice F, Gershon A. Transmission of vaccine strain varicella-zoster virus from a healthy adult with vaccine-associated rash to susceptible household contacts. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1072–5. doi: 10.1086/516514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]