Abstract

Objective

To characterize vaping behavior and nicotine intake during ad libitum e-cigarette access.

Methods

Thirteen adult e-cigarette users had 90 minutes of videotaped ad libitum access to their usual e-cigarette. Plasma nicotine was measured before and every 15 minutes after the first puff; subjective effects were measured before and after the session.

Results

Average puff duration and interpuff interval were 3.5±1.4 seconds (±SD) and 118±141 seconds, respectively. 12% of puffs were unclustered puffs while 43%, 28%, and 17% were clustered in groups of 2–5, 6–10, and >10 puffs, respectively. On average, 4.0±3.3 mg of nicotine was inhaled; the maximum plasma nicotine concentration (Cmax) was 12.8±8.5 ng/mL. Among the 8 tank users, number of puffs was positively correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled, Cmax, and area under the plasma nicotine concentration-time curve (AUC0→90min) while interpuff interval was negatively correlated with Cmax and AUC0→90.

Conclusion

Vaping patterns differ from cigarette smoking. Plasma nicotine levels were consistent with intermittent dosing of nicotine from e-cigarettes compared to the more bolus dosing from cigarettes. Differences in delivery patterns and peak levels of nicotine achieved could influence the addictiveness of e-cigarettes compared to conventional cigarettes.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, vaping topography, addictive potential, vaping patterns, nicotine pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use has increased considerably in recent years among youth and adults.1,2 Although there are safety concerns, it is the efficacy of e-cigarettes as an alternative source of nicotine and tool for smoking cessation which have been most controversial.3,4 Of interest is the addictiveness of e-cigarettes which is expected to influence intensity and prevalence of use in the population. Nicotine delivery and pharmacokinetics (PK) are associated with tobacco product addictiveness.5 We recently showed that 15 puffs from e-cigarettes deliver on average similar levels of nicotine compared to tobacco cigarettes, although the maximum plasma nicotine levels (Cmax) were lower than after smoking a tobacco cigarette.6 Our study and others suggest that newer generations of e-cigarettes are effective nicotine delivery devices.7–9

As e-cigarettes evolve in design and nicotine delivery becomes more efficient, it is important to characterize and monitor patterns of use and vaping topography among users. Vaping topography is a measure of how a person uses or vapes an e-cigarette, and consists of a range of parameters including number of puffs, puff duration, puff volume, puff velocity, and inter-puff interval. Smoking topography of conventional tobacco cigarettes is associated with nicotine dependence or ability to quit;10,11 vaping topography may also be indicative of nicotine dependence among vapers.

Vaping topography influences e-cigarette nicotine delivery in controlled vaping machine experiments12 and is therefore an important determinant of nicotine exposure and abuse liability. Number of puffs and interpuff interval (time between 2 puffs) are important variables to understand patterns of e-cigarette use (spacing of puffs). Patterns of use and topography differ between e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. Smokers generally inhale 10 to 15 puffs in 5 to 8 minutes, and repeat this behavior with each cigarette.13 On the other hand, e-cigarette users may puff intermittently throughout the whole day and puffs may or may not be clustered like tobacco cigarettes. For this study we define a cluster as 2 or more puffs with no more than 60 seconds between the puffs. Clustering of puffs among e-cigarette users has not been adequately explored. In addition, puff duration for e-cigarettes is longer than for tobacco cigarettes.14 Also, puff velocity (flow rate) influences nicotine delivery in tobacco cigarettes15 but not in e-cigarettes.12

Given the abundance and variety of e-cigarette products, e-liquid flavors, and nicotine concentrations, as well as constantly evolving designs, it is important to understand how users vape e-cigarettes and how vaping topography influences nicotine exposure. Some studies have examined e-cigarette topography using computerized handheld devices and/or video analysis.14,16–22 Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, studies have not assessed the relationship between vaping topography and nicotine pharmacokinetic parameters during ad libitum use. This is an important gap to address since e-cigarette users do not use these devices in a standardized way. Since we did not measure topography parameters such as puff velocity and puff volume, we will hereafter use the term vaping behavior to collectively describe the topography variables we measured.

The objective of our study was to characterize vaping behavior, puff clustering, and nicotine intake during a period of ad libitum access among experienced e-cigarette users and to correlate vaping behavior with nicotine exposure and pharmacokinetic parameters.

METHODS

This study was part of a project which examined the clinical pharmacology of a variety of e-cigarettes. It consisted of a standardized session in which we assessed nicotine delivery, systemic retention, and pharmacokinetics, which have been presented elsewhere6 and a 90-minute period of ad libitum access to examine vaping patterns and puffing behavior, reported here.

Participants

A convenience sample of 17 healthy adult e-cigarette users was recruited. Four participants (all males, 3 whites and 1 mixed-race, and median age 22 years (range 19 to 69)) were eligible but did not attend the inpatient session for unknown reasons. Thirteen participants completed the study. Participants were recruited via Craigslist.com and flyers. They were screened for eligibility at a clinical research facility. Exclusive e-cigarette users or dual users who smoked less than 5 tobacco cigarettes per day, who used e-cigarettes at least once daily for 3 months or more, and had saliva cotinine levels greater than 30 ng/mL were eligible (saliva cotinine was measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)).23 Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, use of nicotine metabolism altering medications, use of zero-nicotine e-cigarettes or e-liquid, chronic diseases, and active substance abuse or dependence other than marijuana. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and all participants were financially compensated.

Experimental Procedure

The details and findings of the standardized session which preceded the ad libitum session have been described previously.6 Briefly, participants came to the Clinical Research Center at the San Francisco General Hospital for a 1-day pharmacokinetic study. They came to the hospital the evening before and abstained from e-cigarettes and/or other tobacco products after 10 PM. Participants were awakened at 7:00 AM and an intravenous (IV) line for blood sampling was placed in the forearm at 8:00 AM followed by a light breakfast. Baseline blood was sampled, urine was collected, subjective questionnaires (ie, urge, affect, and withdrawal) were administered, and heart rate measurements were taken by pulse oximeter before e-cigarette use. At approximately 9:30 AM the participants used their usual brand of e-cigarette (and usual e-liquid in tanks and rebuildable atomizer models, RBA), which were supplied by the study. Participants took 15 puffs, one every 30 seconds during the standardized session. Participants exhaled through their mouth after each puff into a sterile polypropylene mouthpiece which was connected to gas dispersion bottles containing dilute hydrochloric acid to assess nicotine retention. After the 15 puffs, participants abstained from e-cigarette use for 4 hours, during which time intermittent blood samples were taken and questionnaires administered.

After 4 hours of abstinence, subjective questionnaires were administered and a blood sample was taken. E-cigarettes were re-filled (if using a tank or RBA style device) and weighed using a microbalance. At 2:00 PM participants were given their usual e-cigarettes (and e-liquid) and were instructed to vape as desired over a 90-minute period of ad libitum access. Blood samples were taken every 15 minutes. At the end of the 90-minute session, the e-cigarette was reweighed and the subjective questionnaires were administered again.

E-cigarette use during the ad libitum session was recorded using a high definition video camera that was positioned to capture the participant puffing on the e-cigarette, including hand and mouth movements. Handheld devices such as the Clinical Research Support System (CReSS Pocket) which measure many topography variables have been validated for evaluation of e-cigarette topography.17 However, these devices were originally designed for use with conventional cigarettes and are adaptable for use with cig-a-likes but are not designed to be used with larger tanks and RBAs. Other than puff velocity and volume, puff topography parameters can be reliably measured using video cameras, as done previously.14,24,25

Subjective Questionnaires

The Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS),26 the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-Brief) modified for e-cigarettes,27 and the Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS)28 were used to measure nicotine withdrawal, craving, and positive and negative affective states, respectively, before and after e-cigarette use. The modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ),29 further modified for e-cigarettes, was used to measure reward after using the e-cigarette.

Analytical Chemistry

Nicotine concentration in plasma was determined by GC-MS/MS, using our published GC-MS method,30 modified for tandem mass spectrometry for improved sensitivity. The limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 0.2 ng/mL. Nicotine in the participants’ e-cigarettes or e-liquids was measured by LC-MS/MS as previously described,6 with an LOQ of 0.4 ng/mg.

Vaping Behavior and Grouping of Puffs

Videos of the ad libitum session were analyzed for vaping behavior variables for each participant, including the total number of puffs and duration of each puff. Puff duration was measured as the time the e-cigarette was placed in the mouth and the mouth was closed to when the e-cigarette was removed or when possible, the time the device was placed in the mouth and the button pressed to when the e-cigarette was removed. In addition, we assessed the interpuff interval as the elapsed time between the end of one puff to the beginning of the next puff. The average interpuff interval was then computed for each participant.

We identified clusters or grouping of puffs by counting the number of puffs with no more than 60 seconds between puffs. Clusters were classified as short (2 to 5 puffs), medium (6 to 10 puffs), and long (greater than 10 puffs), and puffs not within 60 seconds of a preceding puff were classified as an unclustered single puff. We computed the average number of puffs taken in each cluster (ie, 2–5, 6–10, and >10 puffs) and the percentage of puffs relative to the total number of puffs taken in the entire ad libitum session for puffs taken as a single puff, and in clusters of 2–5, 6–10, and >10 puffs.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated from plasma nicotine concentrations using Phoenix WinNonlin 6.3 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA). Time of maximal concentration (Tmax), maximum plasma nicotine concentration (Cmax), and area under the plasma nicotine concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 to 90 minutes (AUC0→90) were estimated using a noncompartmental model and trapezoidal rule. We corrected all measures for baseline values (plasma nicotine concentration immediately before the ad libitum session) in order to assess the changes in plasma nicotine attributed to the ad libitum session only. This was done by estimating the plasma nicotine concentration from baseline levels (pre-ad libitum use) at each sampling time-point using the formula Ct = C0e−Kt, where Ct is the estimated plasma nicotine concentration at a time-point after baseline, C0 is the baseline plasma nicotine concentration, K is the participant’s nicotine elimination rate constant, and t is the elapsed time after baseline. K for each participant was computed from the standardized session (average, 0.0077 min−1; range, 0.0046 to 0.0193 min−1).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed for the number of puffs taken, puff duration (s), interpuff interval (s), amount of e-liquid vaped (mg), amount of nicotine inhaled (mg), Tmax (min), plasma nicotine Cmax (ng/mL), and AUC0→90 (ng/mL min). The amount of nicotine inhaled was computed as the amount of e-liquid vaped (mg) × the concentration of nicotine in the e-liquid (ug/mg). Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between vaping behavior variables and e-liquid nicotine content, amount of e-liquid vaped, amount of nicotine inhaled, Tmax, Cmax, and AUC0→90. Correlations were computed for all participants and for users of tank (2nd generation) devices only, respectively. The number of cig-a-like (n = 2) and RBA (n = 3) users were too small for separate analyses for these e-cigarette designs. We also assessed the cross-correlations between actual nicotine inhaled (as described above), and estimated nicotine inhaled, Tmax, Cmax, and AUC0→90. Estimated amount of nicotine inhaled was determined as the amount of nicotine inhaled per puff from the standardized session (ie, amount of e-liquid vaped from 15 puffs × the concentration of nicotine in the e-liquid divided by 15 puffs) multiplied by the number of puffs taken during the ad libitum session. This was done to determine if one can use average nicotine delivery per puff during the standardized session combined with number of puffs taken during the ad libitum sessions to predict nicotine intake during ad libitum use. Correlation analyses included all participants and tank users only. Other analyses included correlations between nicotine intake and PK between the standardized session and the ad libitum session. Changes in individual items and overall scores for MNWS, QSU, and PANAS were assessed using paired samples t-test. Correlation analysis was also conducted between vaping behavior variables, nicotine intake and PK, and changes in MNWS, QSU, and PANAS and post-vaping mCEQ scores. All analyses were carried out using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Statistical tests were considered significant at α < .05.

RESULTS

Participants

Thirteen participants (6 females, 7 males) were enrolled in the study. The characteristics of the participants, including their usual devices and e-liquid flavors, have been described previously.6 The average age was 38.4 ± 13.1 (mean ± SD) years; 9 were white, 2 were Asian, 1 was black, and 1 was mixed race. Nine participants were self-reported exclusive e-cigarette users, confirmed by their low expired carbon monoxide (CO) levels at screening (range 1 – 4 ppm). Two participants used cig-a-likes, 8 used tanks, and 3 used RBAs. Seven of the 8 tanks used were KangerTech devices. The average nicotine concentration of the e-liquids used was 9.4 ± 4.1 ug/mg (median, 8.6 ug/mg; interquartile range, IQR, 5.7 – 12.6 ug/mg). Average lifetime duration of e-cigarette use was 1.3 ± 1.6 years. Device-type, vaping behavior, nicotine intake and PK were not significantly related to duration of e-cigarette use and sex.

Vaping Behavior

Vaping behavior measures during 90 minutes of ad libitum access to e-cigarettes are presented in Table 1. The average number of puffs taken was 64 ± 38 (median, 71 puffs; IQR, 33 – 84 puffs). The average puff duration of all participants was 3.5 ± 1.4 seconds (median, 3.2 seconds; IQR, 2.6 – 3.9 seconds). The average interpuff interval of all participants was 118 ± 141 seconds (median, 71 seconds; IQR, 50 – 139 seconds).

Table 1.

Vaping behavior and nicotine pharmacokinetics during 90 minutes of ad libitum access to electronic cigarettes

| Participant | Brand | Nicotine concentration in e-liquid (ug/mg) | Number of puffs in 90minutes | Average puff duration (s) | Average interpuff interval (s) | Amount of e-liquid used (mg) | Nicotine inhaled (mg) | Tmax (min) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0→90 (ng/mL min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Tank e-cigarettes | ||||||||||

| 1 | Kanger EVOD2 | 15.3 | 37 | 3.2 | 139 | 166 | 2.5 | 75 | 11.0 | 591 |

| 3 | Kanger T3D | 11.4 | 84 | 2.7 | 57 | 309 | 3.5 | 60 | 10.8 | 568 |

| 5 | Kanger T3D | 15.3 | 123 | 2.0 | 41 | 255 | 3.9 | 90 | 12.6 | 834 |

| 6 | Kanger EVOD | 8.6 | 82 | 3.2 | 60 | 237 | 2.0 | 90 | 9.5 | 608 |

| 7 | Kanger Aerotank V2 | 12.1 | 121 | 2.3 | 43 | 644 | 7.8 | 90 | 18.6 | 1144 |

| 10 | Kanger EVOD | 5.6 | 26 | 5.9 | 181 | 171 | 1.0 | 60 | 2.9 | 200 |

| 12 | Vapor4Life | 5.9 | 98 | 4.3 | 50 | 548 | 3.2 | 60 | 11.5 | 750 |

| 13 | Kanger Protank II | 5.7 | 71 | 1.7 | 74 | 374 | 2.1 | 30 | 6.8 | 457 |

| B. Cartridge e-cigarettes | ||||||||||

| 2 | V2 Cigs Red 18 | 13.9 | 60 | 6.6 | 84 | 258 | 3.6 | 90 | 12.5 | 656 |

| 9 | Blu E-cigarette | 12.6 | 10 | 3.9 | 554 | 29 | 0.4 | 90 | 1.6 | 65 |

| C. Rebuildable atomizers (RBAs) | ||||||||||

| 4 | Vulcan | 5.7 | 33 | 3.2 | 168 | 1349 | 7.7 | 90 | 29.0 | 1669 |

| 8 | K101 | 5.0 | 10 | 3.9 | 7 | 376 | 1.9 | 15 | 10.0 | 603 |

| 11 | Nimbus | 5.0 | 71 | 2.6 | 71 | 2373 | 12.0 | 90 | 29.7 | 1574 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean | 9.4 | 64 | 3.5 | 118 | 545 | 4.0 | 71.5 | 12.8 | 748 | |

| Median | 8.6 | 71 | 3.2 | 71 | 309 | 3.2 | 90 | 11.0 | 608 | |

| SD | 4.1 | 38 | 1.4 | 141 | 641 | 3.3 | 25.4 | 8.5 | 470 | |

| Q1 | 5.7 | 33 | 2.6 | 50 | 237 | 2.0 | 60 | 9.5 | 568 | |

| Q3 | 12.6 | 84 | 3.9 | 139 | 548 | 3.9 | 90 | 12.6 | 834 | |

Note: Subject IDs correspond to subject IDs in a previously published study (reference 6); Tmax, time to maximum plasma nicotine concentration; Cmax, maximum plasma nicotine concentration; AUC0→90, area under the plasma nicotine concentration time curve from 0 to 90 minutes; SD, standard deviation; Q1 is the first quartile; Q3 is the third quartile.

Grouping and Patterns of Puffs

Table 2 presents the grouping or clustering of puffs during the ad libitum session. On average, participants took an unclustered puff 5.2 times, and short, medium, and long clusters were taken 8.6, 2.4. and 0.8 times, respectively. The average number of puffs taken in the short and medium clusters was 2.6 and 6.1 puffs, respectively. Of 13 participants, 6 had at least one long cluster. Among these 6 participants, the average number of puffs taken in the long cluster was 19.6 puffs (SD, 5.0; median, 18.9 puffs). Of all puffs taken during the ad libitum session, 11.9% were unclustered single puffs, and 42.9%, 27.8%, and 16.5% were taken in short, medium, and long clusters, respectively.

Table 2.

Grouping of puffs during 90 minutes of ad libitum access to electronic cigarettes

| Frequency of puff clusters | Average number of puffs per cluster | Percent of total puffs in session (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Subject | 1 puff | 2–5 puffs | 6–10 | >10 puffs | 2–5 puffs | 6–10 puffs | >10 puffs | 1 puff | 2–5 puffs | 6–10 puffs | >10 puffs |

| A. Tank e-cigarettes | |||||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2.6 | 8.0 | 0 | 29.7 | 48.6 | 21.6 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 15.0 | 1.2 | 20.2 | 31.0 | 35.7 |

| 5 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 22.0 | 1.6 | 20.3 | 42.3 | 35.8 |

| 6 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 20.5 | 7.3 | 34.1 | 8.5 | 50.0 |

| 7 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2.8 | 7.3 | 17.3 | 0 | 20.7 | 36.4 | 43.0 |

| 10 | 11 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 42.3 | 57.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 5 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 2.8 | 9.7 | 28.0 | 5.1 | 36.7 | 29.6 | 28.6 |

| 13 | 2 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 2.3 | 8.0 | 0 | 2.8 | 74.6 | 22.5 | 0 |

| B. Cartridge e-cigarettes | |||||||||||

| 2 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 2.8 | 8.7 | 0 | 20.0 | 36.7 | 43.3 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| C. Rebuildable atomizers (RBAs) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 12 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 36.4 | 63.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 11 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 3.1 | 6.3 | 15.0 | 8.5 | 43.7 | 26.8 | 21.1 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | 5.2 | 8.6 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 9.1 | 11.9 | 42.9 | 27.8 | 16.5 |

| Median | 5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2.8 | 7.3 | 0 | 5.1 | 36.7 | 26.8 | 0 |

| SD | 4.8 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 10.7 | 15.0 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 19.7 |

| Q1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 0 | 1.2 | 20.7 | 8.5 | 0 |

| Q3 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2.8 | 8.0 | 17.3 | 20.0 | 57.7 | 36.4 | 35.7 |

Note: Subject IDs correspond to subject IDs in a previously published study (reference 6); SD, standard deviation; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile.

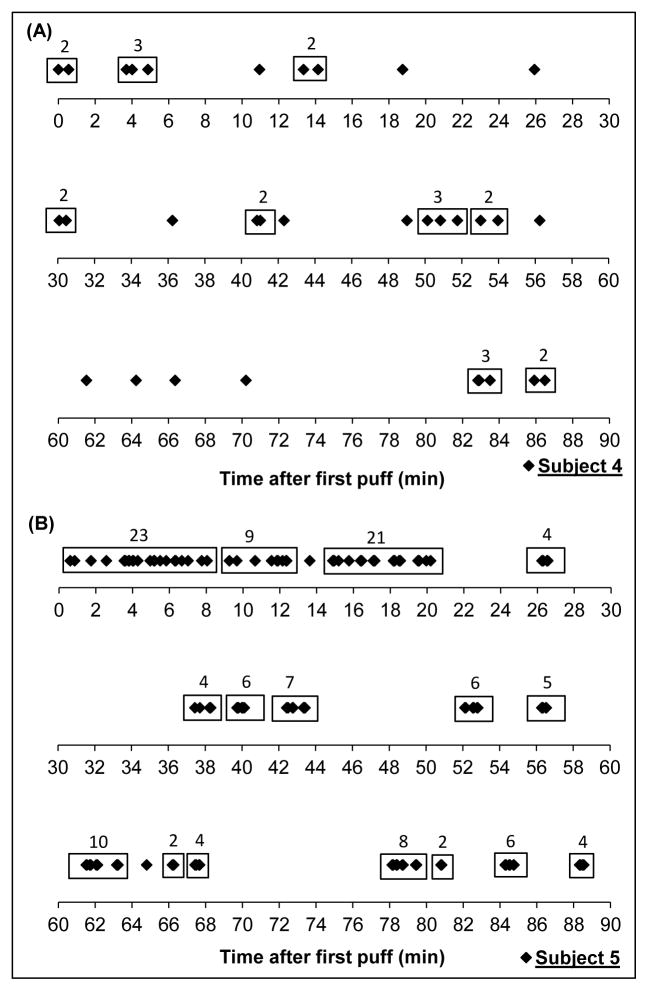

As shown in Figure 1, we observed 2 main patterns of vaping during the ad libitum session. The first pattern included 2 participants who vaped intermittently during the session using unclustered single puffs or short clusters (as depicted by participant 4 in Figure 1A). The second pattern included 9 participants who began the session with at least a medium cluster followed by intermittent vaping, often in short or medium clusters (as depicted by participant 5 in Figure 1B). For the 2 participants who did not fall into these patterns, one participant took 10 puffs over the first 2 minutes of the ad libitum session with no subsequent vaping, and another participant took only 10 puffs total in 3 small clusters spread almost evenly over the ad libitum session (see Figure 2D).

Figure 1.

Vaping pattern of a subject who vaped intermittently in clusters of no more than 3 puffs (A) and a subject who vaped in several clusters of 6–10 and greater than 10 puffs over a 90-minute ad libitum vaping session (B). A cluster is defined as a group of 2 or more puffs with no more than 60 seconds between puffs. Each marker (◆) represents a puff.

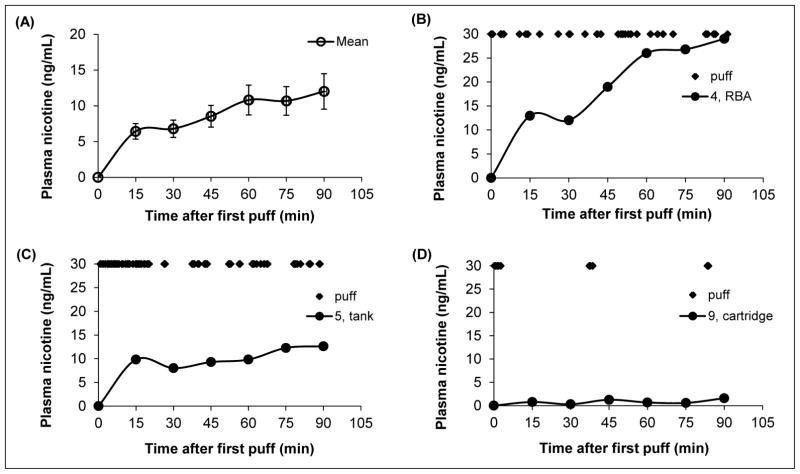

Figure 2.

Average plasma nicotine, corrected for baseline levels [mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM)] in experienced users (n = 13) during 90 minutes of ad libitum e-cigarette access (A); vaping and plasma nicotine profile of subject 4 (B); vaping and plasma nicotine profile of subject 5 (C); and, vaping and plasma nicotine profile of subject 9. Markers (◆) at the top of Figures 2B, 2C, and 2D represent when a puff was taken.

Amount of Nicotine Inhaled and Nicotine Pharmacokinetics

The participants used an average of 545 ± 641 mg of e-liquid during the session, which delivered an average of 4.0 ± 3.3 mg of nicotine (range, 0.4 12.0 mg) (Table 1). The average Cmax was 12.8 ± 8.5 ng/mL (95% CI, 7.7 – 18.0), and ranged between 1.6 to 29.7 ng/mL. The average plasma nicotine profile for all participants is shown in Figure 2A, as well as variations in plasma nicotine between participants (Figures 2B – 2D). The plasma nicotine profiles shown in Figures 2B and 2C correspond to puffing patterns illustrated in Figures 1A and 1B, respectively.

Compared to the standardized session, which has been reported previously,6 amount of nicotine inhaled during the ad libitum session was significantly higher (4.0 ± 3.3 mg vs 1.3 ± 0.7 mg, p = .005) (presented as ad libitum vs standardized session) but Cmax (12.8 ± 8.5 ng/mL vs 8.4 ± 5.1 ng/mL, p = .12) was not significantly different. Nicotine inhaled during the standardized session was significantly correlated with nicotine inhaled (r = 0.61, p = .03), plasma nicotine Cmax (r = 0.70, p = .01), and plasma nicotine AUC (r = 0.71, p = .01) during ad libitum access. Plasma nicotine Cmax during the standardized session was significantly correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled (r = 0.63, p = .02) and AUC during ad libitum access (r = 0.56, p = .048).

Correlations Between Nicotine Pharmacokinetics and Vaping Behavior Variables

Pearson correlation coefficients between nicotine pharmacokinetic parameters and vaping behavior variables are presented in Table 3 for all participants and for users of tanks only, respectively. Vaping behavior variables (numbers of puffs taken, total puffing time, average puff duration, and average interpuff interval) were not significantly correlated with e-liquid nicotine concentration, amount of e-liquid vaped, nicotine inhaled, Tmax, Cmax, and AUC0→90 when all participants were considered. Among tank users only, number of puffs taken was significantly positively correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled (r = 0.74, p = .04), Cmax (r = 0.77, p = .02) and AUC0→90 (r = 0.85, p = .008), and average interpuff interval was significantly negatively correlated with AUC0→90 (r = −0.74, p = .04) and marginally significantly correlated with Cmax (r = −0.69, p = .06).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between vaping behavior variables and nicotine delivery and nicotine pharmacokinetics during 90 minutes of ad libitum access to e-cigarettes

| Number of puffs taken | Total puffing time (s) | Average puff duration (s) | Average interpuff interval (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. All subjects, users of cartridges, tanks, and RBAs (n = 13) | ||||

| E-liquid nicotine (ug/mg) | 0.26 (0.38) | 0.20 (0.51) | −0.03 (0.93) | 0.18 (0.55) |

| E-liquid vaped (mg) | 0.09 (0.76) | −0.02 (0.94) | −0.27 (0.37) | −0.20 (0.51) |

| Nicotine inhaled (mg) | 0.36 (0.23) | 0.16 (0.60) | −0.35 (0.24) | −0.32 (0.29) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.11 (0.72) | −0.31 (0.31) | −0.35 (0.25) |

| Tmax (min) | 0.29 (0.33) | 0.32 (0.29) | 0.02 (0.95) | 0.29 (0.33) |

| AUC0→90 | 0.31 (0.30) | 0.14 (0.64) | −0.35 (0.24) | −0.40 (0.18) |

| B. Users with tanks only (n = 8) | ||||

| E-liquid nicotine (ug/mg) | 0.29 (0.49) | −0.15 (0.72) | −0.48 (0.23) | −0.18 (0.67) |

| E-liquid vaped (mg) | 0.66 (0.08) | 0.64 (0.09) | −0.26 (0.54) | −0.62 (0.10) |

| Nicotine inhaled (mg) | 0.74 (0.04) | 0.39 (0.33) | −0.48 (0.23) | −0.60 (0.11) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.77 (0.02) | 0.48 (0.23) | −0.55 (0.16) | −0.69 (0.06) |

| Tmax (min) | 0.42 (0.30) | 0.31 (0.45) | −0.08 (0.85) | −0.25 (0.56) |

| AUC0→90 (ng/mL min) | 0.85 (0.008) | 0.55 (0.16) | −0.54 (0.16) | −0.74 (0.04) |

Note: Tmax, time to maximum plasma nicotine concentration; Cmax, maximum plasma nicotine concentration; AUC0→90, area under the plasma nicotine concentration time curve from 0 to 90 minutes; RBA is rebuildable atomizer; p-values shown in parentheses.

Among all participants, actual amount of nicotine inhaled was significantly correlated with Cmax (r = 0.94, p < .001) and AUC0→90 (r = 0.92, p < .001) while estimated nicotine inhaled (based on average amount of nicotine inhaled per puff from the standardized session) was not significantly correlated with Cmax (r = 0.44, p = .15) or AUC0→90 (r = 0.48, p = .11). Among tank users only, nicotine inhaled was significantly correlated with Cmax (r = 0.93, p < .001) and AUC0→90 (r = 0.92, p < .001). Estimated nicotine inhaled was also significantly correlated with Cmax (r = 0.83, p = .02) and AUC0→90 (r = 0.83, p = .02) among tank users only. The correlation between actual nicotine inhaled and estimated nicotine inhaled was 0.56 (p = .06) for all participants and 0.94 (p = .002) for tank users only.

Subjective responses

The overall MNWS score decreased significantly from 9.8 to 3.7 (p = .014) (Table 3). Total QSU scores and all individual item scores except vaping “makes me less depressed” decreased significantly (p < .05). PANAS-negative affect decreased significantly (p = .026) while the change in PANAS-positive affect was not significant. The mCEQ subscales (with maximum possible score shown in [ ]) were as follows: Satisfaction [21], 18.5 ± 13.5 (mean ± SD); Reward [35], 22.0 ± 11.5; Aversion [14], 3.5 ± 2.2; Sensations [7], 5.2 ± 3.3; and, Craving Reduction [7], 5.4 (2.9). Subjective measures were not significantly different with sex and type of e-cigarette, with the caveat that most participants used tanks.

When all participants were included, amount of nicotine inhaled, Cmax, and AUC were not significantly correlated with subjective measures. Number of puffs was correlated with change in QSU (r = −0.60, r = .04). Among tank users only, change in MNWS was significantly correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled (r = −0.71, p = .047) and AUC (−0.76, p = .03) while vaping behavior variables were not correlated with subjective measures.

DISCUSSION

During 90 minutes of ad libitum access to e-cigarettes, the average puff duration was 3.5 seconds and the average interpuff interval was about 2 minutes. On average, participants took 5 unclustered single puffs and about 9 short clusters (2 to 5 puffs), 2 medium clusters (6 to 10 puffs), and 1 long cluster (>10 puffs). Of the total number of puffs taken, 12% were unclustered single puffs while approximately 43%, 28%, and 17% were short, medium, and long clusters, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between vaping behavior variables and nicotine PK parameters during ad libitum use has not been presented before. When users of tank devices were considered separately, number of puffs taken was positively correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled. Number of puffs was also positively associated with Cmax and AUC0→90 while interpuff interval was negatively correlated with Cmax and AUC0→90. On the other hand, when all device types were considered (all participants), we found that vaping behavior variables were not significantly correlated with amount of e-liquid vaped, nicotine inhaled, and nicotine PK parameters.

The average puff duration of e-cigarettes observed in this study are consistent with other studies,14,16,18,19 and are longer than reported puff duration of tobacco cigarette smokers.31 On the other hand, the average interpuff interval was longer than other studies that reported interpuff intervals closer to 30 seconds.14,16,17,32 Most of these studies utilized shorter ad libitum sessions than our study, such as 20 minutes, and therefore likely captured the initial cluster of puffs over the first 5 to 15 minutes observed in 9 of our study participants, resulting in shorter average interpuff intervals. Considerable inter-subject variability in vaping topography has been reported.19 Robinson and colleagues assessed vaping topography using a handheld device over a 24-hour period in the participants’ naturalistic settings and identified 3 representative puff topographies: (1) those who take many short puffs (~1.4 second puff duration and interpuff interval of 18 seconds); (2) those who are described as typical, who take puffs of ~3.7 seconds and 49 second-interpuff interval; and (3) those who take few but longer puffs of ~7 seconds and 48 second interpuff interval.19 Given the high inter-subject variability in topography, we agree with Robinson and colleagues that a range of vaping topography patterns should be employed when conducting machine-based evaluation of e-cigarette aerosolization. It also appears, based on observed significant correlations between nicotine inhaled and nicotine PK parameters during the standardized and ad libitum sessions, that nicotine intake and systemic exposure during a standardized session where puff duration is not fixed is predictive of nicotine intake and systemic exposure during a period of ad libitum access to e-cigarettes. (We have not assessed nicotine intake and PK during a standardized session with fixed-puff duration.)

While a medium or long cluster of puffs, which is more likely to resemble cigarette-like smoking, was observed in 10 of 13 participants (77%), most of the puffs were taken in short clusters (43% of total puffs). About 12% of puffs were unclustered single puffs, 28% were in medium clusters, and 17% were in long clusters. This indicates that, on average, vaping patterns are more variable than tobacco cigarette smoking in which each cigarette is puffed about 10 to 15 times in 5 to 8 minutes.13 The dominant vaping pattern we observed entailed beginning with medium and/or long clusters over the first 5 to 20 minutes of the ad libitum session followed by intermittent vaping primarily in short clusters.

On average, 4.0 mg of nicotine was delivered to the participants, as much nicotine as 3–4 typical tobacco cigarettes.33 However, the average plasma nicotine Cmax was 12.8 ng/mL, which is similar to the average plasma nicotine boost from smoking one tobacco cigarette.34,35 This is consistent with the intermittent dosing of nicotine from e-cigarettes compared to the nearly bolus dosing from tobacco cigarettes. The maximum plasma nicotine levels were generally achieved towards the end of the 90-minute session. This suggests that e-cigarette users are not using e-cigarettes to achieve rapid rise in blood nicotine levels as commonly seen among tobacco cigarette smokers but are instead producing a gradual rise over a longer period of time when given free access to e-cigarettes. While some of the participants were able to attain tobacco cigarette-like plasma nicotine levels from 15 puffs (one puff every 30 seconds) during the standardized session, such behavior was rarely seen during ad libitum use. This observation has implications for the abuse liability of e-cigarettes, which would be expected to be less addictive if plasma nicotine Cmax is produced over a long versus short time. While slower nicotine absorption might indicate lower abuse liability, more slowly absorbed forms of nicotine delivery, such as smokeless tobacco, can also be addictive.36,37

The relationship between vaping behavior variables during ad libitum use and nicotine PK has not, to our knowledge, been reported before. Topography variables such as puff volume (a function of flow rate and puff duration) and intercigarette interval have been shown to be associated with nicotine boost in cigarette smokers.38,39 Among tank users only, most of which were of the KangerTech brand, number of puffs was positively correlated with amount of nicotine inhaled, Cmax and AUC0→90, and interpuff interval was negatively correlated with Cmax and AUC0→90. On the other hand, puff duration and interpuff interval were not significantly correlated with Cmax and AUC0→90 when all participants (all e-cigarette designs) were considered. This finding reflects the fact that the design of the device has an important influence on how much e-liquid is aerosolized per puff, and that relationships between puff topography and aerosol exposure cannot be extrapolated across types of device.

We observed strong correlations between the actual amount of nicotine inhaled during the ad libitum session and the estimated amount of nicotine inhaled among tank users only. Computations of the estimated amount of nicotine inhaled during the ad libitum session is based on the average amount of nicotine inhaled per puff during the standardized session multiplied by the number of puffs taken during the ad libitum session, a vaping behavior variable. The estimated amount of nicotine inhaled was also significantly correlated to Cmax and AUC0→90. While we saw that amount of nicotine inhaled during the standardized session was predictive of nicotine inhaled, Cmax, and AUC during periods of ad libitum access for all participants, regardless of device-type, the estimated amount of nicotine inhaled was significantly related to Cmax and AUC only among tank devices. This suggests that predictive models of nicotine intake which include variables that combine nicotine delivery and vaping topography should be specific to e-cigarette designs.

As reported previously, e-cigarettes reduced the urge to smoke/vape and nicotine withdrawal symptoms and increased reward and satisfaction,8,40–42 which is important if e-cigarettes are to be used for successful smoking cessation. Higher amounts of nicotine inhaled and AUC were associated with larger reductions in withdrawal and urge to vape among tank users. While participants reported significant reduction in negative affect (PANAS negative affect score), we did not see a significant increase in the positive affect score, suggesting that e-cigarettes, as used during the study, were used primarily for relief of nicotine withdrawal symptoms and negative affect associated with withdrawal. One caveat is the absolute change in positive and negative affect were similar and the nonsignificant change in PANAS positive affect (p = .09) may be due to a lack of statistical power. As far as we know, PANAS has not been used by others to assess changes in positive and negative affect after e-cigarette use. We previously found significant reduction in PANAS negative affect and nonsignificant changes in PANAS positive affect after 15 puffs in the standardized session.6

Our study has some limitations. Video analysis is limited in the number of vaping topography parameters that can be obtained. However, previous research has shown agreement between video and handheld topography devices in measuring parameters such as puff duration, puff number, and interpuff interval.24,25 In addition, while we did not use independent raters for the video data, previous research has also shown high interrater reliability for video data (r ≥ 0.94).24 Further, it was not feasible to capture exhaled breath after each puff to assess systemic retention as we did during the standardized session. As a result, we do not know how much of the nicotine taken into the mouth was inhaled and retained in the lungs. Nicotine retention was relatively high (~94%) during the standardized session and we can assume that the same is true during ad libitum use. Finally, the study was conducted in a research ward setting; our findings may not be generalizable to vaping in a natural setting.

In conclusion, e-cigarette vaping patterns differed from typical patterns of smoking tobacco cigarettes; most puffs were clustered in groups of 2 to 5 puffs. Patterns of use and vaping behavior variables versus nicotine concentration-time curves also differed from those described with conventional tobacco cigarette smoking. During 90 minutes of ad libitum access, experienced e-cigarette users took in, on average, as much nicotine as 3–4 typical tobacco cigarettes. The average plasma nicotine levels were similar to reported nicotine boosts from smoking one tobacco cigarette, consistent with the intermittent dosing of nicotine from e-cigarettes compared to the more nearly bolus dosing from a tobacco cigarette, which may have implications for e-cigarette abuse liability. Vaping behavior variables were related to Cmax and AUC0→90 among tank users only and not among all device types, demonstrating that puffing topography cannot be related to nicotine or e-cigarette aerosol exposure across e-cigarettes of different design. This suggests that effective e-cigarette regulation should be e-cigarette design/type-specific.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

This paper adds to nascent e-cigarette literature on vaping behavior among e-cigarette users and presents novel data on the relationship between vaping behavior and nicotine pharmacokinetic parameters during ad libitum access to e-cigarettes. The findings have several regulatory implications.

First, e-cigarette users vape in patterns that differ from tobacco cigarette smoking, in that they take longer puffs and group their puffs in shorter clusters. Current measures of daily e-cigarette use, such as number of puffs per day, may be highly imprecise. Researchers should explore other measures of use such as number of short, medium, and long clusters of puffs taken within a specified time (eg, 1 hour), where a short cluster is 2–5 puffs, medium is 6–10 puffs, and long is greater than 10 puffs, and examine how the distribution of puffs vary within and between users.

Second, the vaping behavior variables measured on human participants during ad libitum access to e-cigarettes in this study will enable researchers to design more relevant vaping machine studies to assess nicotine intake and toxicant exposure.

Third, participants vaped intermittently throughout the 90-minute session. This led to a gradual rise in plasma nicotine levels which peaked at the end of the session. This is different from the rapid rise in plasma nicotine which follows near-bolus nicotine dose from cigarette smoking. Given that a rapid rise in plasma nicotine is associated with greater abuse liability of tobacco products, these results suggest that while e-cigarettes may be addictive (they deliver nicotine), the addictiveness of these products may be dependent on the manner in which they are vaped. Researchers should compare nicotine dependence among vapers who dose intermittently to those who administer tobacco cigarette-like bolus doses. This may inform regulations on product design and nicotine delivery.

Finally, we did not observe significant associations between vaping behavior and nicotine intake and pharmacokinetics among all subjects but we did when we considered tank users only. This supports the importance of collecting data on device-type in all e-cigarette-related studies.

Table 4.

Withdrawal symptoms, urge to use e-cigarettes and affect before and after 90 minutes of ad libitum access to electronic cigarettes

| Scale | Pre | Post | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MNWS (0, none; 4, severe) | |||

| Angry, irritable, frustrated | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | .012 |

| Anxious, nervous | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.9) | .39 |

| Depressed mood, sad | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | .34 |

| Desire or craving to smoke | 2.4 (1.1) | 0.6 (0.8) | <.001 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.4) | .021 |

| Increased appetite, hungry | 1.2 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.6) | .03 |

| Restless | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.7 (0.6) | .04 |

| Impatient | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.1) | .14 |

| Dizziness | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.8) | .34 |

| Increased coughing | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | 1 |

| Nausea | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.3) | .34 |

| Sorethroat | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.4) | .34 |

| MNWS total score (of 48) | 9.8 (7.4) | 3.7 (0.2) | .014 |

| QSU (0, strongly disagree; 7, strongly agree) | |||

| Desire for e-cigarette now | 5.6 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.0) | < .001 |

| Nothing better than to vape now | 4.3 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.0) | < .001 |

| Would vape if possible | 5.5 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.8) | < .001 |

| Would control thing better | 3.2 (2.0) | 1.7 (1.2) | .013 |

| All I want is an e-cigarette | 4.1 (2.2) | 1.5 (1.1) | .001 |

| Urge for e-cigarette | 5.7 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.6) | < .001 |

| An e-cigarette would taste good | 5.4 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.6) | < .001 |

| Would do anything for an e-cigarette | 3.4 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.4) | .006 |

| Vaping would make me less depressed | 2.1 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.1) | .054 |

| Will vape as soon as possible | 5.3 (1.9) | 2.0 (1.4) | < .001 |

| QSU total score (of 7) | 4.4 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.1) | < .001 |

| PANAS | |||

| PANAS positive affect score (of 50) | 23.2 (7.6) | 26.8 (10.0) | .09 |

| PANAS negative affect score (of 50) | 13.3 (3.9) | 10.5 (10.8) | .026 |

Notes: Presented as mean (SD); MNWS, Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; QSU, Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Scale

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Emilio Fernandez, Jennifer Ko, and Marian Shahid for clinical coordination; Marian Shahid for video analysis; Dr. Natalie Nardone for project management; and Kristina Bello and Lisa Yu for performing analytical chemistry. This study was supported by grant number 1P50CA180890 from the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products and P30 DA012393 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and was carried out in part at the Clinical Research Center at San Francisco General Hospital Medical Center (NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR024131). K. Ross received fellowship support from National Cancer Institute grant 5R25CA113710-08. Preliminary findings from this study have been presented at the annual meetings of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco in 2015 and 2016. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Neal Benowitz serves as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies that market smoking cessation medications and has served as a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. The other authors have no conflicts to declare.

Contributor Information

Gideon St.Helen, Assistant Professor, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Kathryn C. Ross, Postdoctoral fellow, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Delia A. Dempsey, Physician, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Christopher M. Havel, Chemist, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Peyton Jacob, III, Research Chemist, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Neal L. Benowitz, Professor, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

References

- 1.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen K, et al. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):219–227. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(2):116–128. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNeill A, Brose L, Calder R, et al. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. [Accessed April 15, 2016];A report commissioned by Public Health England. 2015 https://regulatorwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf.

- 5.Henningfield JE, Keenan RM. Nicotine delivery kinetics and abuse liability. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(5):743. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.StHelen G, Havel C, Dempsey D, et al. Nicotine delivery, retention, and pharmacokinetics from various electronic cigarettes. Addiction. 2016;111(3):535–544. doi: 10.1111/add.13183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vansickel AR, Weaver MF, Eissenberg T. Clinical laboratory assessment of the abuse liability of an electronic cigarette. Addiction. 2012;107(8):1493–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawkins L, Corcoran O. Acute electronic cigarette use: nicotine delivery and subjective effects in regular users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231(2):401–407. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farsalinos KE, Spyrou A, Tsimopoulou K, et al. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices. Scientific reports. 2014;4(4133) doi: 10.1038/srep04133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strasser AA, Pickworth WB, Patterson F, et al. Smoking topography predicts abstinence following treatment with nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(11):1800–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franken FH, Pickworth WB, Epstein DH, et al. Smoking rates and topography predict adolescent smoking cessation following treatment with nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(1):154–157. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talih S, Balhas Z, Eissenberg T, et al. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):150–157. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Herrera B. Nicotine intake and dose response when smoking reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(6):703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsalinos KE, Romagna G, Tsiapras D, et al. Evaluation of electronic cigarette use (vaping) topography and estimation of liquid consumption: implications for research protocol standards definition and for public health authorities’ regulation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(6):2500–2514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10062500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond D, Collishaw NE, Callard C. Secret science: tobacco industry research on smoking behaviour and cigarette toxicity. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):781–787. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton KJ, June KM, O’Connor RJ. Initial puffing behaviors and subjective responses differ between an electronic nicotine delivery system and traditional cigarettes. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behar RZ, Hua M, Talbot P. Puffing Topography and Nicotine Intake of Electronic Cigarette Users. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0117222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hua M, Yip H, Talbot P. Mining data on usage of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) from YouTube videos. Tob Control. 2013;22(2):103–106. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson R, Hensel E, Morabito P, et al. Electronic cigarette topography in the natural environment. PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0129296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans SE, Hoffman AC. Electronic cigarettes: abuse liability, topography and subjective effects. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 2):ii23–ii29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spindle TR, Breland AB, Karaoghlanian NV, et al. Preliminary results of an examination of electronic cigarette user puff topography: The effect of a mouthpiece-based topography measurement device on plasma nicotine and subjective effects. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):142–149. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YH, Gawron M, Goniewicz ML. Changes in puffing behavior among smokers who switched from tobacco to electronic cigarettes. Addict Behav. 2015;48:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacob P, 3rd, Wilson M, Benowitz NL. Improved gas chromatographic method for the determination of nicotine and cotinine in biologic fluids. J Chromatogr. 1981;222(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blank MD, Disharoon S, Eissenberg T. Comparison of methods for measurement of smoking behavior: mouthpiece-based computerized devices versus direct observation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(7):896–903. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross KC, Juliano LM. Smoking through a topography device diminishes some of the acute rewarding effects of smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):564–571. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becoña E, Vázquez FL, Fuentes MaJ, et al. Anxiety, affect, depression and cigarette consumption. Pers Individ Dif. 1998;26(1):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose JE, Westman EC, Behm FM, et al. Blockade of Smoking Satisfaction Using the Peripheral Nicotinic Antagonist Trimethaphan. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62(1):165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob P, 3rd, Yu L, Wilson M, et al. Selected ion monitoring method for determination of nicotine, cotinine and deuterium-labeled analogs: absence of an isotope effect in the clearance of (S)-nicotine-3',3'-d2 in humans. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1991;20(5):247–252. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammond D, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. Smoking topography, brand switching, and nicotine delivery: results from an in vivo study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(6):1370–1375. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goniewicz ML, Kuma T, Gawron M, et al. Nicotine levels in electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):158–166. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hukkanen J, Jacob P, III, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(1):79–115. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson F, Benowitz N, Shields P, et al. Individual differences in nicotine intake per cigarette. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(5):468–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JM, Gandhi KK, Lu S-E, et al. Higher nicotine levels in schizophrenia compared with controls after smoking a single cigarette. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(8):855–859. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henningfield J, Fant R, Tomar S. Smokeless tobacco: an addicting drug. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(3):330–335. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh MM, Hilton JF, Ernster VL, et al. Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of spit tobacco use in a college athlete population. Addict Behav. 1994;19(4):411–427. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross KC, Dempsey DA, Helen GS, et al. The influence of puff characteristics, nicotine dependence, and rate of nicotine metabolism on daily nicotine exposure in African American smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(6):936–943. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatsukami DK, Pickens RW, Svikis DS, et al. Smoking topography and nicotine blood levels. Addict Behav. 1988;13(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vansickel AR, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):267–270. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, et al. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):98–103. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etter J-F. Explaining the effects of electronic cigarettes on craving for tobacco in recent quitters. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]