Abstract

Hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are very rare. We report a primary hepatic PEComa with a review of the literature. A 56-year-old women presented with a nodular mass detected during the management of chronic renal failure and chronic hepatitis C. Diagnostic imaging studies suggested a nodular hepatocellular carcinoma in segment 5 of the liver. The patient underwent partial hepatectomy. A brown-colored expansile mass measuring 3.2×3.0 cm was relatively demarcated from the surrounding liver parenchyma. The tumor was mainly composed of epithelioid cells that were arranged in a trabecular growth pattern. Adipose tissue and thick-walled blood vessels were minimally identified. A small amount of extramedullary hematopoiesis was observed in the sinusoidal spaces between tumor cells. Tumor cells were diffusely immunoreactive for human melanoma black 45 (HMB45) and Melan A, focally immunoreactive for smooth muscle actin, but not for hepatocyte specific antigen (HSA).

Keywords: Hepatic, PEComa, HMB45, Melan A

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, the WHO defined PEComas as “mesenchymal tumors composed of histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells [1]”. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas) as mesenchymal tumors composed of distinctive cells that show a focal association with blood vessel walls and usually express melanocytic and smooth-muscle markers [2]. Bonetti et al were the first group to propose the concept of a PEComa family [3], which include angiomyolipoma (AML), clear cell sugar tumor of lung (CCST), lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and a group of histologically and immunophenotypically similar tumors which includes primary extrapulmonary sugar tumor, clear cell myomelanocytic tumor, abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelioid cells, PEComa arising at a variety of soft tissue and visceral sites. PEComas show a wide anatomical distribution, but most arise in the retroperitoneum, abdominopelvic region, uterus, and gastrointestinal tract [4,5].

Hepatic PEComas are very rare [6,7]. A gold standard for identification using diagnostic imaging studies is lacking and instead, the diagnosis of hepatic PEComa is obviously made on the basis of positive immunohistochemical staining for HMB45 and Melan A. Herein, we presented a case of partial hepatectomy specimen of primary hepatic PEComa occurring in 56-year-old women and accomplished a review of literature.

CASE REPORT

A 56-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic hepatic mass that unexpectedly detected during the follow-up monitoring and treatment of chronic renal failure and chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody was positive in serum but hepatitis B virus surface antigen and autoantibodies against anti-nuclear antigen and anti-double strand DNA were not found. Quantitative analysis for HCV RNA was 836,000 IU/mL and HCV RNA genotype was 1b in serum. Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) level was 15 mAU/mL in preoperative analysis. Ten years ago, since she had suffered from acute pyelonephritis and multifocal renal abscess, renal function was gradually declined and proceeded to chronic renal failure and underwent hemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. No evidence of tuberous sclerosis was found.

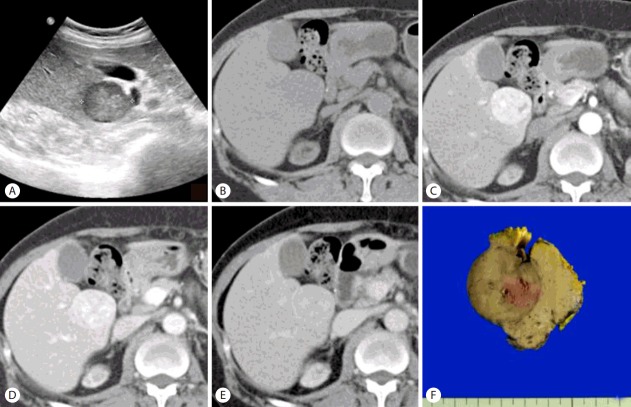

Ultrasonography (US) revealed a slightly heterogeneous hypoechoic nodule in segment 5 of the liver (S5) but this was not seen in the US examination taken at 3 years ago (Fig. 1A). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with 3 phase enhanced was performed. Pre-contrast CT scan (Fig. 1B) shows a low-density mass of S5 of the liver with well-defined border. Contrast-enhanced CT scans show the lesion is heterogeneously and significantly enhanced on arterial phase (Fig. 1C), slightly hypodense on portal venous phase (Fig. 1D) and enhancing rim on delayed phase (Fig. 1E), suggestive of hepatocellular carcinoma in the background of diffuse liver disease. Ultimately, she underwent partial hepatectomy. On gross examination, the resected specimen of the liver was 4.5×4.5×3.0 cm in dimensions and 29.3 gm in weight and a prominent bulging portion was centered on the specimen showing diffuse nodularity. On section, the mass was measured 3.2×3.0 cm and a relatively well-demarcated but not encapsulated and showed brown to gray color and expansile growth pattern (Fig. 1F). Hemorrhage or necrosis was not identified grossly.

Figure 1.

Ultrasonography reveals a slightly heterogeneous hypoechoic nodule in segment 5 of the liver (S5) (A). Pre-contrast CT scan (B) shows a low-density mass of S5 of the liver with well-defined border. Contrast-enhanced CT scans show the lesion is heterogeneously and significantly enhanced on arterial phase (C), slightly hypodense on portal venous phase (D) and enhancing rim on delayed phase (E), suggestive of hepatocellular carcinoma in the background of diffuse liver disease. On section, the mass measures 3.2×3.0 cm and a relatively well-demarcated but not encapsulated and shows brown to gray color and expansile growth pattern (F).

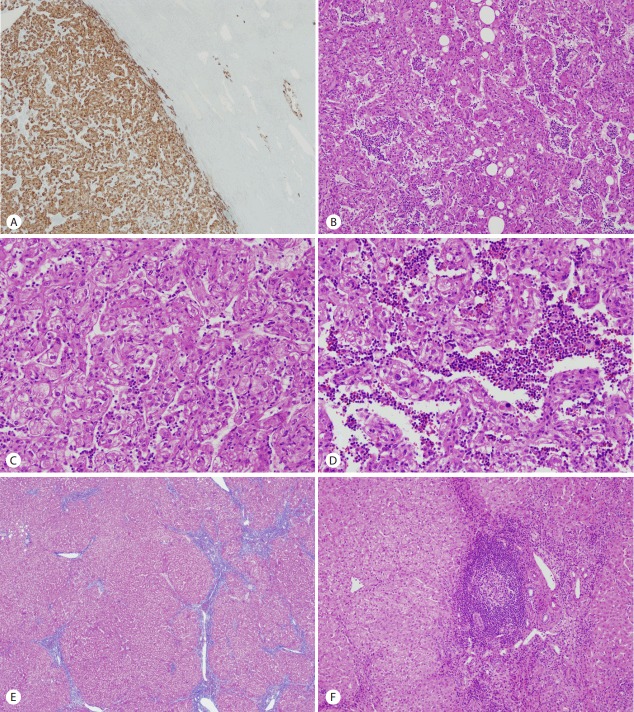

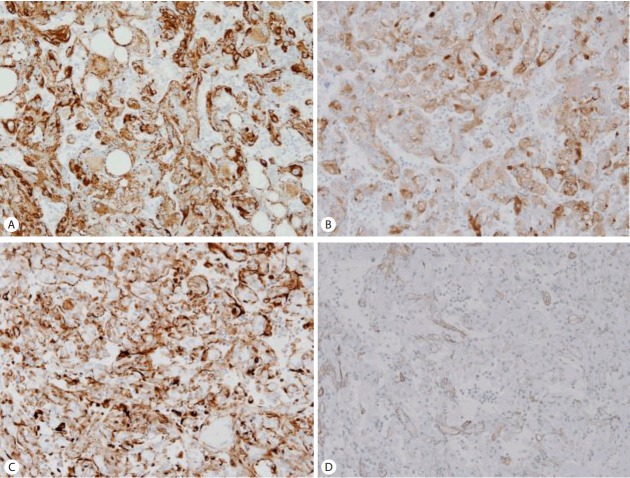

On histopathologic findings, the tumor was well-circumscribed along the edge of the tumor but focal foci of infiltrative growth into the surrounding non-tumorous liver parenchyme were seen in the immunostaining of HMB45 (Fig. 2A). The tumor mainly composed of epithelioid cells and arranged in trabecular growth pattern (Fig. 2B). The epithelioid tumor cells had abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinct cell border, eccentrically located round nuclei with small nucleoli, and foci of mild to moderate nuclear atypism (Fig. 2C). Mitotic figure or necrosis was absent. The nests or trabecular were surrounded by thin-walled capillary vessels. Adipose tissue and thick-walled blood vessels were minimally identified. Somewhat amount of extramedullary hematopoiesis was recognized in the sinusoidal spaces between the tumor cells (Fig. 2D). The surrounding non-tumorous liver parenchyme showed chronic hepatitis with early cirrhotic change (Fig. 2E) and foci of lymphoid aggregate in some portal tracts (Fig. 2F). The tumor cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for HMB45 (1:40, Dako, CA, USA) (Fig. 3A), Melan A (1:50, Dako) (Fig. 3B), and vimentin (1:50, Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) (Fig. 3C) and focally immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA, 1:100, Novocastra) (Fig. 3D) but negative for hepatocyte specific antigen (HSA, 1:40, Novocastra), α-fetoprotein (α-FP, 1:50, Novocastra), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA, 1:40, Novocastra), pan-cytokeratin (pan-CK, 1:200, Novocastra), CD10 (1:50, Novocastra), D2-40 (pre-dilution, Dako), S100 (1:200, Novocastra), synaptophysin (1:100, Novocastra), chromogranin (1:50, Novocastra), desmin (1:50, Dako), and c-kit (1:600, Dako). Ki-67 labeling index was 3%.

Figure 2.

The tumor was well-circumscribed along the edge of the tumor but focal foci of infiltrative growth into the surrounding non-tumorous liver parenchyme were seen in the immunostaining of HMB45 (×40) (A). The tumor mainly composed of epithelioid cells and arranged in trabecular growth pattern (×100) (B). The epithelioid tumor cells had abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinct cell border, eccentrically located round nuclei with small nucleoli, and foci of mild to moderate nuclear atypism (×200) (C). Extramedullary hematopoiesis was recognized in the sinusoidal spaces between the tumor cells (×200) (D). The surrounding non-tumorous liver parenchyme showed chronic hepatitis with early cirrhotic change (Masson trichrome stain, E) and foci of lymphoid aggregate in some portal tracts (×100) (F).

Figure 3.

The tumor cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for HMB45 (A), Melan A (B), and vimentin (C) and focally immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (D). (A-D ×200).

After hepatectomy, she received the abdominal operation twice due to acute appendicitis and intra-abdominal abscess but the evidence of recurrence or metastasis was not found during the follow-up period of eight months.

DISCUSSION

PEComas other than angiomyolipoma (AML) and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) are rare and markedly more frequent in females than males (female-to-male ratio, 6:1), with a wide age range and a peak in young to middle-aged adults. Most PEComas other than AML and LAM are sporadic and a small fraction of PEComas are closely related with the genetic changes of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and deletion of 16p, the locus of the TSC2 gene, which suggests the oncogenesis of PEComas as a TSC2-associated neoplasm [8]. PEComas show a wide anatomical distribution, but most arise in the retroperitoneum, abdominopelvic region, uterus, and gastrointestinal tract [4,5]. Hepatic PEComas are very rare. Maebayashi et al. identified 33 cases with primary hepatic PEComas from 25 articles and 40 cases with epithelioid AML from 17 articles [6]. It occurs principally in adults, with a wide age range (10-86 years) and female predominance (female-to-male ratio, 2:1 to 5:1). Most patients are asymptomatic or have nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, and the tumors are found incidentally. Large lesions cause epigastric pain and rarely, rupture with hemoperitoneum occurs in large subcapsular tumors. Our present case was 56-year-old woman and she was not associated with tuberous sclerosis and presented with asymptomatic hepatic mass that unexpectedly detected during the follow-up monitoring and treatment of chronic renal failure and chronic hepatitis C, which are considered to be unrelated to PEComas.

The enhanced and drainage imaging patterns of hepatic PEComas are similar to those of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Maebayashi et al suggested that PEComas should still be considered when blotchy vascular pattern within the tumor are present and no signs of hemorrhage within the tumor and no abnormalities are found in the background parenchyma and the results of hepatitis virus markers are negative [6]. Our present case was chronic hepatitis C and showed diffuse early cirrhotic change in the background liver parenchyma. Furthermore, the enhanced and drainage imaging patterns were nearly identical those of HCC pattern in the retrospective examination of our CT scans. The histopathologic differential diagnoses of PEComa are quite extensive and influenced by the sites of the tumor origin and morphologic predominance (spindled versus epithelioid). Our present case was consistent with monomorphic variants of PEComas, composed almost exclusively of epithelioid cells and with less well pronounced blood vessels and fat cells. In the liver, most of the PEComas may be of this type [9]. The epithelioid morphology of the tumor cells and the trabecular pattern may misjudge to the erroneous diagnosis of HCC. The observation of large clear cells or large cells with eosinophilic condensation around the nucleus alerts the pathologists to the possibility of a PEComa. For confirmation, immunohistochemical stains for HMB45 or Melan A should be performed. In our case, the tumor cells were diffusely and strongly immunoreactive for HMB45 and Melan A but not for HSA. Other differential diagnoses include epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE), paraganglioma, and metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and adrenocortical carcinoma. The neoplastic cells of EHE exhibit epithelioid, dendritic, or intermediate features and show the characteristic vacuolated signet ring-cell-like features representing intracytoplasmic lumina sometimes containing erythrocytes and are immunoreactive for factor VIII-associated antigen, CD31, and CD34. Primary nonfunctioning paraganglioma confined to the liver have been rarely reported and the tumor cells are immunoreactive for chromogranin, neuron-specific enolase, and synaptophysin and the surrounding sustentacular cells are immunoreactive for S100 protein [10]. Metastatic carcinoma from kidney or adrenal glands could be excluded from the absence of the tumor in the primary sites. Like our case, there are often foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the hepatic PEComa.

At present, a normal counterpart or origin of perivascular epithelioid cells (PEC) is not fully known, but some hypotheses have been suggested. One is that PEC are originated from multipotent stem cells of the neural crest that can manifest dual phenotypes of smooth muscle and melanocytic differentiation; a second is that PEC have a myoblastic origin with a subsequent gaining of micromorphological changes that produces the phenotypes of melanocytic markers; a third is that PEC are originated from the pericytes [11]. Immunohistochemically, PEC manifest of the expression of myogenic and melanocytic markers, such as HMB45, HMSA-1, Melan A, microophtalmia transcription factor (Mitf), actin and, less commonly desmin [9,12].

Most authors consent that criteria for malignancy and the biologic behavior of PEComas have not been sufficiently established. This may be partly attributable to the paucity of reported cases and partly to histologic tumor cell heterogeneity, various nomenclature, and organ-specificity of the origin sites. The criteria for malignancy in PEComas of soft tissue and gynecologic origin are determined by mitotic activity, necrosis, marked nuclear atypia, and pleomorphism [5]. Folpe et al proposed a provisional categorization of PEComas into benign, uncertain malignant potential (UMP), and malignant neoplasm [5]. The worrisome features (less than 5 cm in size, noninfiltrative, low to moderate nuclear grade and cellularity, mitotic activity less than 1/50 high power fields (HPF), no coagulative necrosis or vascular invasion) are not identified in resected specimens and categorize into benign. Tumors of UMP had either nuclear pleomorphism/multinucleated giant cells only or tumor size greater than 5 cm. Tumors with two or more worrisome features categorize into malignant. Recently, they reclassified that PEComas with none of the above worrisome features are benign, while PEComas with one of these features are of UMP, and PEComas with more than one features are clearly malignant [13]. Although the majority of reported PEComas have behaved in a benign fashion, an important minority have demonstrated malignant behavior with locally destructive recurrence and distant metastasis. In the literature review, four cases of malignant PEComas or angiomyolipoma with local recurrence or metastasis were reported in liver [14-17]. But we think that several other cases can probably exhibit local recurrence or metastasis in long-term follow up. Ahn et al pointed out that this might be attributable to the fact that the follow-up durations of the reported cases were relatively short [7]. Parfitt et al reported a case of hepatic PEComa that lacked these worrisome features but later brought to unexpected clinical course of extensive metastasis during a long term follow-up [15]. They suggested the stratification of these lesions into relative-risk categories may offer a more sensible approach, rather than attempting to use morphology to define a truly benign subset of PEComas. Our present case showed only one of the above worrisome features, that is, infiltrative growth and thus could be categorized into UMP. However, the area of infiltrative growth was focal and was not prominently seen in hematoxylin-eosin stain (HE stain) but detected in the immunostains of HMB45 and Melan A. Therefore, we think that thoughtful tissue sampling, serial sections and the immunohistochemical staining with HMB45 or Melan A are inevitably necessary for the exact determination of biologic behavior in the individual cases and a long-term follow up will be needed in our present case.

In conclusion, we presented a case of primary hepatic PEComa with uncertain malignant potential in a 56-year-old woman and inspected the nature of PEC, the importance of thoughtful examination in the diagnosis of hepatic PEComa, and the necessity of a more sensible approach and broad investigation for the stratification of the biologic behavior of PEComas.

Abbreviations

- AML

angiomyolipoma

- CCST

clear cell sugar tumor of lung

- CT

computed tomography

- EHE

epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HMB45

human melanoma black 45

- HSA

hepatocyte specific antigen

- LAM

lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- PEComa

perivascular epithelioid cell tumor

- PIVKA-II

protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II

- TSC

tuberous sclerosis complex

- UMP

uncertain malignant potential

- US

ultrasonography

- WHO

world health organization

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World Health Organization classification of tumours. In: Mertens F, ed. Pathology and genetics of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 221–222. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. World Health Organization classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Fourth Edition. Vol 5. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. pp. 230–231. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G. PEC and sugar. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:307–308. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Paulino AF, Taboada EM, Meehan SA, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239–1246. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558–1575. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173232.22117.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maebayashi T, Abe K, Aizawa T, Sakaguchi M, Ishibashi N, Abe O, et al. Improving recognition of hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5432–5441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn JH, Hur B. Primary perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. Korean J Pathol. 2011;45(Suppl 1):S93–S97. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF, Liu CY, Wang JS, Chai CY, et al. Constant allelic alteration on chromosome 16p (TSC2 gene) in perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa): genetic evidence for the relationship of PEComa with angiomyolipoma. J Pathol. 2008;214:387–393. doi: 10.1002/path.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Manfrin E, Colombari R, et al. The perivascular epithelioid cell and related lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 1997;4:343–358. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corti B, D’Errico A, Pierangeli F, Fiorentino M, Altimari A, Grigioni WF. Primary paraganglioma strictly confined to the liver and mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:945–949. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone CH, Lee MW, Amin MB, Yaziji H, Gown AM, Ro JY, et al. Renal angiomyolipoma: further immunophenotypic characterization of an expanding morphologic spectrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:751–758. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0751-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zavala-Pompa A, Folpe AL, Jimenez RE, Lim SD, Cohen C, Eble JN, et al. Immunohistochemical study of microophtalmia transcription factor and tyrosinase in angiomyolipoma of the kidney, renal cell carcinoma, and renal and retroperitoneal sarcomas: comparative evaluation with traditional diagnostic markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:65–70. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folpe AL, Kwiatkowski DJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalle I, Sciot R, de Vos R, Aerts R, van Damme B, Desmet V, et al. Malignant angiomyolipoma of the liver: a hitherto unreported variant. Histopathology. 2000;36:443–450. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parfitt JR, Bella AJ, Izawa JI, Wehrli BM. Maliganant neoplasm of perivascular epithelioid cells of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1219–1222. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1219-MNOPEC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen TT, Gorman B, Shields D, Goodman Z. Malignant hepatic angiomyolipoma: report of a case and review of literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:793–798. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181607349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng YF, Lin Q, Zhang SH, Ling YM, He JK, Chen XF. Malignant angiomyolipoa in the liver: a case report with pathological and molecular analysis. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]