Abstract

Maternal feeding is a frequent intervention target for the prevention of early childhood obesity but longitudinal associations between feeding and child overweight are poorly understood. This observational cohort study sought to examine the cross-lagged associations between maternal feeding and overweight across ages 21, 27, and 33 months. Feeding was measured by maternal self-report (n=222) at each age. Child weight and length were measured. Cross-lagged analysis was used to evaluate longitudinal associations between feeding and overweight, adjusting for infant birth weight, maternal body mass index, maternal education, and maternal depressive symptoms. The sample was 50.5% white, 52.3% male and 37.8% of mothers had a high school education or less. A total of 30.6%, 29.2%, and 26.3% of the sample was overweight at each age, respectively. Pressuring to Finish, Restrictive with regard to Amount, Restrictive with regard to Diet Quality, Laissez-Faire with regard to Diet Quality, Responsiveness to Satiety, Indulgent Permissive, Indulgent Coaxing, Indulgent Soothing, and Indulgent Pampering each tracked strongly across toddlerhood. There were no significant associations between maternal feeding and child overweight either in cross-sectional or cross-lagged associations. Our results do not support a strong causal role for feeding in childhood overweight. Future work longitudinal work should consider alternative approaches to conceptualizing feeding and alternative measurement approaches.

Keywords: feeding, infant, child, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Maternal feeding is often conceptualized in five domains. Pressuring feeding is characterized by seeking to increase the amount of food consumed. Restrictive feeding is characterized by seeking to limit the types and quantity of food consumed. Responsive feeding is characterized by attending to hunger and satiety cues. Indulgent feeding is characterized by not limiting the quantity or quality of food consumed. Laissez-faire feeding is characterized by not limiting food and also interacting little during feeding.

Maternal feeding is believed to contribute to childhood obesity risk, and has frequently been a target for interventions to prevent obesity in early childhood (Campbell et al., 2008; Daniels et al., 2009; Savage, Birch, Marini, Anzman-Frasca, & Paul, 2016; Taveras et al., 2011). The literature examining associations between maternal feeding and child obesity risk, however, is conflicting (Faith, Scanlon, Birch, Francis, & Sherry, 2004; Vollmer & Mobley, 2013). Measuring both maternal feeding and child weight status longitudinally provides the opportunity to evaluate temporal associations, which can identify potential intervention targets. For example, if pressuring or restrictive feeding temporally precede the development of overweight, they may be targets for intervention. If, on the other hand, maternal feeding changes following the development of child overweight, feeding may be reactive as opposed to causal and therefore a less viable intervention target.

Few observational studies have measured both maternal feeding and child weight status longitudinally (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory, Paxton, & Brozovic, 2010; Jansen et al., 2014; Lumeng et al., 2012; Rhee et al., 2009; Rodgers et al., 2013; Thompson, Adair, & Bentley, 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010; Worobey, Islas Lopez, & Hoffman, 2009) and findings have been mixed. Findings may be mixed due to differences in study populations or differences in measurement of maternal feeding. For example, the ages of children in prior work range from 3 months (Thompson et al., 2013; Worobey et al., 2009) to 10 years (Thompson et al., 2013). Samples were recruited from Australia (Gregory et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013), Portugal (Afonso et al., 2016), the United Kingdom (Webber et al., 2010), and the United States (Faith et al., 2004; Lumeng et al., 2012; Rhee et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Worobey et al., 2009). The number of longitudinal measurement points were primarily two (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2014; Rhee et al., 2009; Rodgers et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber, et al., 2010) occasionally three (Lumeng et al., 2012; Worobey et al., 2009), and in one study five (Thompson et al., 2013). Intervals between these measurements ranged from a minimum of three months (Thompson et al., 2013; Worobey et al., 2009) to a maximum of three years (Afonso et al., 2016), with most studies having an interval of about two years (Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2014; Rhee et al., 2009; Webber et al., 2010). Study cohorts were primarily white, with few exceptions (Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015). Sample sizes ranged broadly from fewer than 100 (Faith et al., 2004; Worobey et al., 2009) to more than 4000 (Jansen et al., 2014), with most studies having sample sizes from 100 to 400.

Approaches to measurement of maternal feeding in these longitudinal studies varied broadly. Some studies used videorecorded observational measures (Lumeng et al., 2012; Worobey et al., 2009). Most studies used the Child Feeding Questionnaire (Afonso et al., 2016; Birch et al., 2001; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Jansen et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013; Webber et al., 2010). One study used a single question items (Rhee et al., 2009). Other questionnaires used included the Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire (Thompson et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2009), Preschool Feeding Questionnaire (Baughcum et al., 2001; Rodgers et al., 2013), Parent Feeding Style Questionnaire (Rodgers et al., 2013; Wardle, Sanderson, Guthrie, Rapoport, & Plomin, 2002), Control Over Eating Questionnaire (Ogden, Reynolds, & Smith, 2006; Rodgers et al., 2013), Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire (Musher-Eizenman & Holub, 2007; Rodgers et al., 2013), the Parental Feeding Practices Questionnaire (Tschann et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015), the Overt/Covert Control Scale (Ogden et al., 2006), and the Maternal Feeding Attitudes Scale (Kramer, Barr, Leduc, Boisjoly, & Pless, 1983; Worobey et al., 2009). Each of these measures conceptualizes feeding slightly differently. Finally, few of these longitudinal studies have examined stability of feeding over time (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Lumeng et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013; Webber, Cooke, et al., 2010), and all but two of these (Lumeng et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2013) were in children who were preschool aged or older.

Overall, few studies have examined these associations in children younger than age 3 years (Lumeng et al., 2012; Rodgers et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013; Worobey et al., 2009). Of studies involving United States populations (Faith et al., 2004; Lumeng et al., 2012; Rhee et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Worobey et al., 2009), few included a cohort that was diverse with regard to race/ethnicity and included a substantial proportion of low-income children (Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015). Examining potential contributors to excessive weight gain among low-income children is especially important given the higher prevalence of overweight in this population (Cunningham, Kramer, & Narayan, 2014). Therefore, within a diverse cohort of low-income children followed longitudinally at ages 21, 27, and 33 months, we sought to address two main objectives: (1) To describe maternal feeding and its change or stability across this age range; and (2) To examine the cross-lagged associations between maternal feeding and overweight during toddlerhood.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

Recruitment occurred between 2011 and 2014. Participants were recruited via flyers posted in community agencies serving low-income families. The study was described as examining whether children with different levels of stress eat differently. Inclusion criteria were: (1) the biological mother was the legal guardian; (2) mother had an education level less than a 4-year college degree; (3) mother was at least 18 years old; (4) the family was eligible for Head Start, Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program, or Medicaid; (5) the family was English-speaking; (6) the child was between 21 and 27 months old; (7) the child was born at a gestational age ≥ 36 weeks; and (8) the child had no food allergies or significant health problems, perinatal or neonatal complications, or developmental delays. Mothers provided written informed consent. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Mother-child dyads were invited to participate in three waves of data collection at child ages 21, 27, and 33 months. The data collection procedures at each age spanned across 5 days. Data were collected regarding eating behavior and biobehavioral self-regulation. A total of 244 dyads participated. Most (n = 186) dyads entered the study when the child was age 21 months, but 58 entered the study when the child was age 27 months to maximize recruitment. Measures obtained at study entry are henceforth referred to as “baseline” measures. This report is limited to children whose mother completed the feeding questionnaire for at least one age point and children who provided at least one anthropometric measurement.

A total of 222 of the 244 participants completed a feeding questionnaire during at least one age point and anthropometry during at least one age point. These 222 participants included in this analysis did not differ from the excluded participants with regard to child sex, child age, maternal BMI, maternal education, maternal depressive symptoms, food security, family structure, or race/ethnicity. A total of 42 children (18.9%) participated at only one age point, 73 (32.9%) participated at only two age points, and 107 (48.2%) participated at all three age points. Mother-child dyads who participated at two or three age points did not differ at baseline from those who participated at only one with regard to child sex, child age, maternal BMI, maternal education, maternal depressive symptoms, food security, or family structure. Non-Hispanic white children were more likely to participate at two or three age points, compared to Hispanic or non-white children (p=0.01).

Measures

We used the Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire (IFSQ) to measure mothers’ feeding (Thompson et al., 2009). The IFSQ was chosen because of its strengths in comparison to other available measures in the literature at the time the study began. First, other available measures asked mothers to report on behaviors only in the first 12 months of life (Baughcum et al., 2001; Hurley, Black, Papas, & Caufield, 2008), or were validated in children (Birch et al., 2001; Hughes, Power, Fisher, Mueller, & Nicklas, 2005) slightly older than the children aged 21 to 33 months in this study. The face validity of the question items in these questionnaires developed for other age ranges was also uncertain (i.e., a large number of questions focused on early bottle feeding or a large number of questions assumed greater receptive and expressive language development in the child). The IFSQ asked mothers to think about feeding a “12 month old to 2 year old.” Finally, the IFSQ included a focus on diet quality as opposed to quantity alone.

Items in the IFSQ are answered on a 5-point scale (1 to 5), with higher scores indicating more of the given type of feeding, with reverse scoring applied as appropriate. Response options were never, seldom, half of the time, most of the time, and always for behaviors, and disagree, slightly disagree, neutral, slightly agree, and agree for beliefs. The IFSQ contains 83 items which generate 13 subscales. To reduce participant burden we retained 9 subscales: Pressuring: Finish (8 items; α = .67–.70 across age points), Restrictive: Amount (4 items; α = .64–.70), Restrictive: Diet Quality (7 items; α = .73–.77), Laissez-Faire: Diet Quality (6 items; Cronbach’s α = .59–.68), Responsive: Satiety (7 items; α = .61–.68), Indulgent: Permissive (8 items; α = .79–.86), Indulgent: Coaxing (8 items), Indulgent: Soothing (8 items; α = .83–.86), and Indulgent: Pampering (8 items; α = .82–.89).

Weight and length were measured by trained research staff. Weight-for-length was calculated and percentiled based on United States Centers for Disease Control Growth Charts. Overweight was defined as a weight-for-length for age and sex > 85th percentile. Mothers’ weight and height were measured and body mass index (BMI) calculated.

Mothers reported child sex, race and ethnicity, maternal education, and family structure (single mother versus not). Mothers completed the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977); response options range from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time) and are summed so that a higher score indicates more symptoms (range: 0–60). The United States Department of Agriculture 18-item Household Food Security Survey (Bickel, Nord, Price, Hamilton & Cook, 2000) categorizes households as food secure versus not. Mothers reported child birth weight, which was converted to a z-score adjusted for gestational age and sex using reference data based on National Center for Health Statistics Natality Data Sets (Oken, Kleinman, Rich-Edwards, & Gillman, 2003).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Univariate statistics were used to describe the sample. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs and Chi square were used to test whether feeding or overweight prevalence differed across 21, 27, and 33 months.

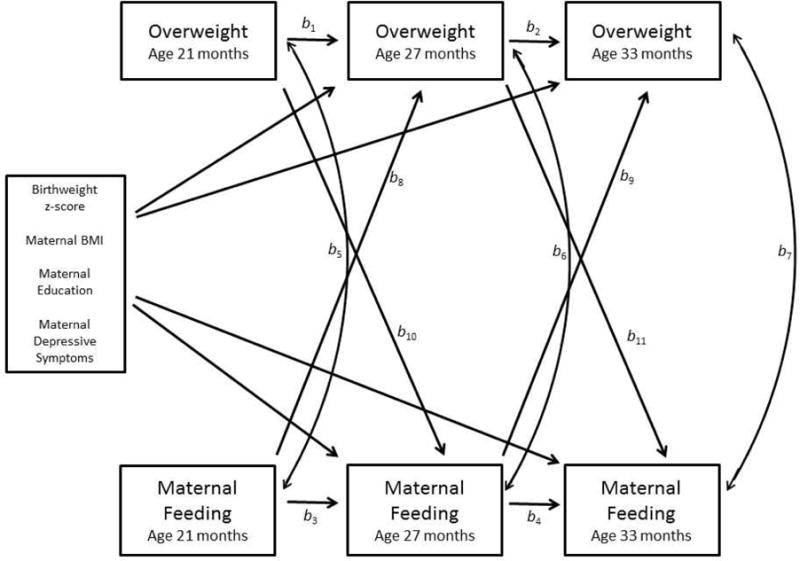

Path models were conducted (using MPLUS version 4.1; Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA) to test the concurrent and cross-lagged associations between feeding and overweight at ages 21, 27, and 33 months (Figure 1). This approach estimates the stability in feeding at individual level measured by the auto-correlation or longitudinal correlation. Bayesian estimation technique in MPLUS was used to fit models which contained both continuous and binary variables. Bayesian posterior predictive checks (PPC) using Chi-square statistics and the corresponding posterior predictive p-values (ppp) were used to assess the goodness of fit in each model (Gelman, 2004). We controlled for infant birthweight in these models given prior work linking infant birth weight with maternal feeding (Blissett & Farrow, 2007; Hurley et al., 2008). We also controlled for maternal BMI, maternal education, and maternal depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for longitudinal associations between maternal feeding and child overweight in toddlerhood

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The sample was 52.3% male, 50.5% white, 25.7% black, and 13.1% Hispanic. Among the mothers, (37.8%) had an education level of a high school diploma or less. Depressive symptoms, as measured by the CES-D, were greater than in the general population but consistent with ratings in low-income U.S. mothers of young children (Campbell-Grossman et al., 2016; Hall, Williams, & Greenberg, 1985). The sample size of participants contributing to analyses at each age is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (at baseline unless otherwise noted), n = 222

| Variable | N (%) or Mean (Standard Deviation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Sex | |||||

| Female | 106 (47.7) | ||||

| Male | 116 (52.3) | ||||

| Child Race | |||||

| White | 112 (50.5) | ||||

| Black | 57 (25.7) | ||||

| Biracial | 48 (21.6) | ||||

| Other | 4 (1.8) | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | ||||

| Child Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 29 (13.1) | ||||

| Not Hispanic | 192 (86.5) | ||||

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | ||||

| Child Birthweight z-score | − 0.2 (1.0) | ||||

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 32.4 (9.3) | ||||

| Maternal Education | |||||

| < high school | 30 (13.5) | ||||

| High school | 37 (16.7) | ||||

| General Education | 17 (7.7) | ||||

| Diploma | |||||

| Some college courses | 116 (52.3) | ||||

| 2 year college degree | 22 (9.9) | ||||

| Single parent | |||||

| Yes | 45 (23.9) | ||||

| No | 143 (76.1) | ||||

| Maternal CES-D score | 12.3 (10.0) | ||||

| Food Secure | |||||

| Yes | 136 (67.0) | ||||

| No | 67 (33.0) | ||||

| 21 months | 27 months | 33 months | Test statistic | p-value | |

| Child overweight | |||||

| Yes | 49 (30.6) | 52 (29.2) | 40 (26.3) | Χ2(2)=3.26 | .20 |

| No | 111 (69.4) | 126 (70.8) | 112 (73.7) | ||

| Feeding | |||||

| Pressuring: Finish | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.8) | F(2,85)=1.88 | .16 |

| Restrictive: Amount | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.0) | F(2,84)=1.42 | .25 |

| Restrictive: Diet Quality | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | F(2,84)=1.17 | .32 |

| Laissez-Faire: Diet | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | F(2,84)=0.09 | .92 |

| Quality | |||||

| Responsive: Satiety | 4.6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.4) | F(2,84)=2.64 | .08 |

| Indulgent: Permissive | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.8) | F(2,84)=1.46 | .24 |

| Indulgent: Coaxing | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.6) | F(2,84)=1.90 | .16 |

| Indulgent: Soothing | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.6) | F(2,84)=1.27 | .29 |

Table 2.

Sample size contributing to analysis at each age

| 21m | 27m | 33m | Only 21m | Only 27m | Only 33m | Only 21 and 27m | Only 27 and 33m | Only 21 and 33m | Complete for 21, 27, and 33m | Any time point | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entered study at 21m and had complete anthropometry or IFSQ subscales | 166 | 130 | 119 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 2 | 10 | 107 | 169 |

| Entered study at 27m and had complete anthropometry or IFSQ subscales | 0 | 53 | 41 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 53 |

| Total participants | 166 | 183 | 160 | 29 | 13 | 0 | 20 | 43 | 10 | 107 | 222 |

IFSQ = Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire; m=months

Cross-lagged analysis results for the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 are presented in Table 3. Overweight status tracked strongly between ages 21 and 33 months. Maternal feeding also tracked strongly between ages 21 and 33 months, though not as strongly as weight status. There were no significant associations between maternal feeding and child overweight either in cross-sectional or cross-lagged associations.

Table 3.

Path coefficients for model shown in Figure 1 in total sample (n =222)

| Path | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Longitudinal associations of Ovwt | Longitudinal associations of maternal feeding | Concurrent associations of ovwt and maternal feeding | Cross-lagged associations Maternal feeding predicting future ovwt | Cross-lagged associations of ovwt predicting future maternal feeding | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Maternal feeding variable | Ovwt 21m → Ovwt 27m |

Ovwt 27m → Ovwt 33m |

Maternal feeding 21m → Maternal feeding 27m |

Maternal feeding 27m→ Maternal feeding 33m |

Ovwt 21m → Maternal feeding 21m |

Ovwt 27m → Maternal feeding 27m |

Ovwt 33 mos → Maternal feeding 33m |

Maternal feeding 21m → Ovwt 27m |

Maternal feeding 27m→ Ovwt 33m |

Ovwt 21 mos → Maternal feeding 27m |

Ovwt 27m → Maternal feeding 33m |

|

| |||||||||||

| b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | b5 | b6 | b7 | b8 | b9 | b10 | b11 | |

| Pressuring: Finish ppp=.42

|

2.19* | 1.14* | 0.69* | 0.69* | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.19 | 0.19 | −0.22 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Restrictive: Amount ppp=.23

|

2.19* | 1.20* | 0.62* | 0.65* | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.21 | 0.32 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.13 |

| Restrictive: Diet Quality ppp=.30

|

2.07* | 1.40* | 0.67* | 0.57* | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.28 | −0.18 | 0.51 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| Laissez-Faire: Diet Quality ppp=.24

|

2.11* | 1.19* | 0.59* | 0.69* | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.12 | 0.33 | 0.07 | −0.05 |

| Responsive: Satiety ppp=.33

|

2.13* | 1.16* | 0.31* | 0.43* | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | −0.11 | 0.45 | 0.06 | −0.19 |

| Indulgent: Permissive ppp=.24

|

2.09* | 1.21* | 0.74* | 0.63* | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.20 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Indulgent: Coaxing ppp=.23

|

2.15* | 1.18* | 0.68* | 0.53* | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.18 | −0.36 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Indulgent: Soothing ppp=.09

|

2.05* | 1.28* | 0.56* | 0.50* | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.36 | −0.25 | −0.01 | 0.16 |

| Indulgent: Pampering ppp=.10 | 2.06* | 1.19* | 0.59* | 0.46* | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

p<.05. Adjusting for birth weight z-score, maternal BMI, maternal education, and maternal depressive symptoms (CES-D score); ovwt = overweight, ppp= posterior predictive p-values, m=months

DISCUSSION

There were two key findings in this study. First, maternal feeding was notably stable across toddlerhood. Second, maternal feeding showed no association with the child being overweight, neither concurrently, as a predictor of overweight, nor in response to child overweight.

Stability of Feeding

We found that pressuring feeding was relatively stable across toddlerhood (r = .69), consistent with prior work (r = .49–.83) (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Webber et al., 2010). The only study that did not find stability in pressuring feeding over time used observational as opposed to self-report methods (Lumeng et al., 2012). We also found that restrictive feeding was relatively stable across toddlerhood (r = .57–.67), which is also consistent with prior reports of stability (r =.28–.59) in later childhood (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Webber et al., 2010). In general, stability of monitoring tends to be lower in prior work (r = .23–.53) (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Webber et al., 2010) We did not have a measure of monitoring, but our measure of laissez-faire feeding for diet quality showed slightly higher stability than restrictive feeding (r = .59–.69). We also found that indulgent feeding was relatively stable across toddlerhood (r = .46–.74), while the stability of responsiveness to satiety was moderate (r = .31 – .43). To our knowledge, the stability of these types of feeding have not been previously reported in the literature.

Concurrent Associations between Feeding and Overweight

We found no concurrent associations between any type of feeding and overweight status. Overall, our generally null findings are consistent with the prior studies that have also examined concurrent associations and generally found null associations (Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2013). The few exceptions include reports that less pressuring to finish (Thompson et al., 2013), greater intrusive prompting to eat (Lumeng et al., 2012), and less monitoring (Faith et al., 2004) were all linked to greater body mass index z-score. These reports finding associations were all among U.S. samples, as in our study, included children ranging from 3 months to 7 years, and samples sizes ranging from 57 to 1218. Two of the three reports finding associations used maternal self-report measures (one with the CFQ (Faith et al., 2004) and one with the IFSQ (Thompson et al., 2009), as in our study), and one study used videorecorded observational measures (Lumeng et al., 2012). In summary, we were unable to identify a pattern among studies that identified concurrent associations between maternal feeding and child body mass index z-score based on sample characteristics or methodology that might explain our null findings in relation to these prior reports.

Associations between Feeding and Future Overweight

We found no prospective associations between maternal feeding and future overweight, largely consistent with prior work in this same age range using the same measure (Thompson et al., 2013). Many prior studies have found either no association between pressuring feeding and future markers of adiposity (Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Lumeng et al., 2012; Webber et al., 2010) or have found an inverse association (Afonso et al., 2016; Jansen et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015). No study that measured both pressuring feeding and child weight longitudinally found a positive association between greater pressure and greater future overweight. The studies, including our own, that found no association did not differ systematically from studies that found an inverse association in any way that we were able to identify with regard to sample size, sample characteristics, or methodology. Thus, although it remains unclear why some studies find no association and others find that greater pressure to eat is associated with a lower risk of future overweight among children, it is noteworthy that no study has found that greater pressure to eat is associated with a higher risk of future overweight.

We found no association between restriction and future overweight. These results are similar to most prior studies which have also found no association of restrictive feeding with future overweight (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2010; Rodgers et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber et al., 2010). Two studies have found greater restriction associated with greater future adiposity (Jansen et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2013). There was again no identifiable difference in the sample size, sample characteristics, or methodology used in the two studies that found greater restriction to be associated with greater future overweight as compared to the studies that did not find an association.

We found no prospective association between laissez-faire feeding and future overweight, similar to the one prior study using the same measure in a similar age range (Thompson et al., 2013). Laissez-faire can be conceptualized as the opposite of monitoring. Of the seven prior studies that have examined feeding and weight longitudinally, three have found that greater monitoring is associated with less future overweight (Afonso et al., 2016; Faith et al., 2004; Rhee et al., 2009), while four found no association (Gregory et al., 2010; Rodgers et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber et al., 2010). There was again no identifiable pattern in sample size, sample characteristics, or methodology to explain these disparate results.

We did not find an association between greater responsiveness to satiety and future overweight. This contrasts with the single prior study we could identify examining both responsiveness to satiety and weight status longitudinally. In this prior study, greater maternal sensitivity to infant feeding cues at 6 months was associated with subsequent lesser increases in adiposity from 6 to 12 months (Worobey et al., 2009). Our study used maternal self-report and was in a slightly older age range. It is possible that maternal responsiveness to satiety or sensitivity to cues is more closely related to weight gain in infancy as opposed to later toddlerhood, as in our study. It is also possible that the association is identifiable by observation of maternal behavior, but not by maternal self-report. Self-report is influenced by reporting bias, either due to social desirability or differing interpretations of the meaning of different descriptions of feeding. Observational approaches, however, are limited by capturing only single feeding episodes, and feeding approaches may certainly vary depending on child behavior as well as foods served. Further work is needed to reconcile the meaning of disparate results based on self-report versus observational feeding methodologies.

Associations between Overweight and Future Feeding

We found no prospective associations between overweight and future feeding, consistent with prior work with this measure in this age range in a U.S. sample which also found primarily null associations (Thompson et al., 2013).

We did not find an association between child overweight and future pressure. Prior work has often found that greater adiposity predicts future declines in pressure (Afonso et al., 2016; Jansen et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2013; Tschann et al., 2015; Webber et al., 2010). Again, there was no evident pattern with regard to sample size, sample characteristics, or methodology to explain our null findings compared to these other studies. We could not identify any study that found a positive association between overweight and future pressure.

We did not find an association between overweight and future restriction. Studies have found that greater adiposity predicts future increases in restriction (Afonso et al., 2016; Jansen et al., 2014; Tschann et al., 2015) though one prior study in toddlers with the same measure showed a decrease in restriction (Thompson et al., 2013). There was again no pattern to explain these discrepant findings.

We did not find an association between overweight and future laissez faire feeding. Prior work has found greater adiposity linked with increases in monitoring (only in girls) (KE Rhee et al., 2009), less decline in monitoring (Webber et al., 2010), or no association (Jansen et al., 2014). The prior studies finding that weight was associated with changes in monitoring were in school-age children. It is possible that greater monitoring of children’s eating in response to their weight status does not emerge until later childhood.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The longitudinal design is a strength, but due to the high-risk nature of the study cohort, attrition was high and there were missing data. Results may not be generalizable to other study populations outside low-income toddlers in the United States. The internal reliability of the feeding subscales was modest at some ages. Measures of maternal feeding were by self-report and videorecorded observational measures of feeding may have yielded different results. Future work should consider longitudinal videorecorded observational measures of child feeding. In addition, children’s eating behavior, temperament, or other characteristics of the child were not examined as contributors to feeding and will be an important focus of future work. Recently, there has been increasing movement in the field towards differentiating feeding styles, practices, and beliefs (Patrick, Hennessy, McSpadden, & Oh, 2013). The measure used in the current study combines beliefs and behaviors into a single subscale. Future work should consider differentiating feeding styles, practices, and beliefs, which may explain discrepant findings across studies. This analysis also did not examine maternal perceptions of child weight, which may also be relevant to the conceptual model. Despite these limitations, the study was able to describe maternal feeding in a very young age group longitudinally in a diverse population at a low socioeconomic level.

Conclusion

We found that maternal feeding was relatively stable over a year beginning at child age 21 months, suggesting that timing of interventions targeting maternal feeding may need to begin in infancy. We found no evidence that differences in feeding precede future changes in child weight status, nor that changes in weight status precede future changes in feeding. Overall, the pattern of results in our own and prior work suggests that maternal feeding either does not change in response to child weight status, or if it does change, it changes in such a way as to attempt to reduce excess adiposity. It seems unlikely that our null findings were due to power limitations, given that a number of prior studies with larger sample sizes have also had null results. It also seems unlikely that our null findings are only generalizable to a specific age range (toddlers), or a specific demographic group (low-income, U.S.), given that similar findings have been reported in samples across childhood and around the world. Additional studies that examine both child weight and maternal feeding longitudinally and employ cross-lagged analyses in large sample sizes with power to detect small but clinically significant effects will be important.

In summary, our results, which largely align with a small but growing body of evidence from longitudinal studies in the literature, call into question the value of targeting maternal feeding as a strategy for overweight prevention. The etiology of childhood obesity requires ongoing study. Future work on maternal feeding might consider focusing more closely on how mothers’ changes in feeding in response to children’s growth patterns may affect a range of outcomes related to psychological health, family functioning, and general well-being. Furthermore, providing mothers evidence-based guidance on how to change parenting to respond to a child’s excessive rate of weight gain is a critical need.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: R01HD069179

Abbreviations

- WLZ

weight-for-length z-score

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions:

JCL, KR, and ALM designed research; JCL, KR and ALM conducted research; LR and NK analyzed data; JCL wrote the paper; JCL had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Afonso L, Lopes C, Severo M, Santos S, Real H, Durão C, Oliveira A. Bidirectional association between parental child-feeding practices and body mass index at 4 and 7 y of age. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(3):861–867. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum AE, Powers SW, Johnson SB, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Jain A, Whitaker RC. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22(6):391–408. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G, N M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Measuring food security in the United States: Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. 2000 Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx#guide.

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001;36(3):201–210. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blissett J, Farrow C. Predictors of maternal control of feeding at 1 and 2 years of age. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31(10):1520–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Grossman C, Hudson DB, Kupzyk KA, Brown SE, Hanna KM, Yates BC. Low-income, African American, adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and social support. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(7):2306–2314. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Ball K, McCallum Z. The Infant Feeding Activity and Nutrition Trial (INFANT) an early intervention to prevent childhood obesity: cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC public health. 2008;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KMV. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(5):403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels LA, Magarey A, Battistutta D, Nicholson JM, Farrell A, Davidson G, Cleghorn G. The NOURISH randomised control trial: positive feeding practices and food preferences in early childhood-a primary prevention program for childhood obesity. BMC public health. 2009;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith M, Scanlon K, Birch L, Francis L, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity research. 2004;12(11):1711–1722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Parental feeding attitudes and styles and child body mass index: Prospective analysis of a gene-environment interaction. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e429–e436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1075-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A. Bayesian data analysis. Boca Raton, Fla: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory J, Paxton S, Brozovic A. Maternal feeding practices, child eating behaviour, and body mass index in preschool-aged children: a prospective analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7(55):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LA, Williams CA, Greenberg RS. Supports, stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income mothers of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75(5):518–522. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.75.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Fisher JO, Mueller S, Nicklas TA. Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite. 2005;44(1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas MA, Caufield LE. Maternal symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety are related to nonresponsive feeding styles in a statewide sample of WIC participants. The Journal of nutrition. 2008;138(4):799–805. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.4.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen PW, Tharner A, van der Ende J, Wake M, Raat H, Hofman A, Tiemeier H. Feeding practices and child weight: is the association bidirectional in preschool children? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;100(5):1329–1336. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Barr RG, Leduc DG, Boisjoly C, Pless IB. Maternal psychological determinants of infant obesity. Development and testing of two new instruments. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1983;36(4):329–335. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Ozbeki TN, Appugliese DP, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH. Observed assertive and intrusive maternal feeding behaviors increase child adiposity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2012;95(3):640–647. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher-Eizenman D, Holub S. Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2007;32(8):960–972. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J, Reynolds R, Smith A. Expanding the concept of parental control: a role for overt and covert control in children’s snacking behaviour? Appetite. 2006;47(1):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.03.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman M. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatrics. 2003;3(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H, Hennessy E, McSpadden K, Oh A. Parenting styles and practices in children’s obesogenic behaviors: Scientific gaps and future research directions. Childhood obesity. 2013;9(s1):S-73–S-86. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–340. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee K, Coleman S, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, Corwyn R, Davidson N, Lumeng J. Maternal feeding practices become more controlling after and not before excessive rates of weight gain. Obesity. 2009;17(9):1724–1729. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Massey R, Campbell KJ, Wertheim EH, Skouteris H, Gibbons K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: a prospective study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage JS, Birch LL, Marini M, Anzman-Frasca S, Paul IM. Effect of the insight responsive parenting intervention on rapid infant weight gain and overweight status at age 1 year: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics. 2016;170(8):742–749. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, Haines J, McDonald J, Price S, Oken E. First steps for mommy and me: a pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(8):1217–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Pressuring and restrictive feeding styles influence infant feeding and size among a low-income African-American sample. Obesity. 2013;21(3):562–571. doi: 10.1002/oby.20091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(2):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Gregorich SE, Penilla C, Pasch LA, de Groat CL, Flores E, Butte NF. Parental feeding practices in Mexican American families: initial test of an expanded measure. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Martinez SM, Penilla C, Gregorich SE, Pasch LA, de Groat CL, Butte NF. Parental feeding practices and child weight status in Mexican American families: a longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer RL, Mobley AR. Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite. 2013;71:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obesity research. 2002;10(6):453–462. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L, Cooke L, Hill C, Wardle J. Child adiposity and maternal feeding practices a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;92(6):1423–1428. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.30112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L, Hill C, Cooke L, Carnell S, Wardle J. Associations between child weight and maternal feeding styles are mediated by maternal perceptions and concerns. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;64(3):259–265. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worobey J, Islas Lopez M, Hoffman DJ. Maternal behavior and infant weight gain in the first year. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2009;41(3):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]