Abstract

Among 14–24 year-olds who used drugs and were recruited from an emergency department, we examined two-year trajectories of sexual risk behaviors. We hypothesized that those in higher risk trajectories would have more severe substance use, mental health concerns, and dating violence involvement at baseline. Analyses identified three behavioral trajectories. Individuals in the highest risk trajectory had a more severe profile of baseline alcohol use, marijuana use, dating violence involvement, and mental health problems. Future research will examine longitudinal differences in risk factors across trajectories. Understanding risk factors for sexual risk behavior trajectories can inform the delivery and tailoring of prevention interventions.

Keywords: drug use, adolescents, sexual risk, longitudinal trajectories

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, adolescents and emerging adults have disproportionately acquired new HIV infections [1]. For example, 13–24 year-olds comprised about 17% of the U.S. population in 2010, but accounted for about one-quarter of new infections [2]. HIV also disproportionately occurs in urban areas [3] and among African Americans [1]. Most youth who acquire HIV are infected either through sexual contact or through sexual contact combined with injection drug use, as opposed to perinatal transmission [1]. Substance use is linked to HIV transmission, since individuals who use drugs are more likely to engage in riskier behaviors while acutely intoxicated due to the disinhibiting effects of substances [2]. The developmental period of adolescence and emerging adulthood is accompanied by increased HIV risk, as both substance use and sexual risk behaviors are typically initiated during adolescence and reach a peak during emerging adulthood [4–9].

The co-occurrence of substance use and HIV risk is supported by problem behavior theory [10], which suggests that risk behaviors cluster and youth who engage in one risk behavior are also more likely to engage in others (e.g., substance use and/or risky sex and/or violence, etc.). This developmental period is distinguished by increases in sensation seeking, novelty seeking, and limitations in cognitive and behavioral control, which may amplify risk-taking in some youth [11, 12]. Sexual risk behaviors are also impacted by factors across different levels of socio-ecological influence (e.g., individual, peer/family relationships, community), which can fluctuate over time [13, 14]. For example, Voisin and colleagues’ conceptual framework [13] suggests that community violence exposure is associated with HIV risk behaviors, but is mediated by factors at other socio-ecological levels (e.g., peer influences, individual psychological distress).

Given this social and developmental context, and the role of substance use in HIV transmission, identifying distinct trajectories of sexual risk behaviors among substance-using adolescents and young adults can provide important information for targeted prevention and intervention programs that attempt to disrupt longitudinal involvement in risk behaviors. Examining such risk trajectories can help inform precision medicine approaches to prevention which take individual and environmental factors into account when treating or preventing disease. Therefore, identifying distinct subgroups, particularly among individuals presenting in clinical settings, can aid in determining appropriate interventions at the point of care, based on baseline markers of elevated risk. For example, youth in low-risk trajectories may need minimal intervention (e.g., universal prevention), whereas individuals in high-risk trajectories may need more intensive prevention programming and referrals to specialty services (e.g., treatment for co-occurring mental health concerns, case management to address other psychosocial concerns). Although school-based research and interventions may have utility for reducing some aspects of sexual risk [15], clinical settings provide a window of opportunity to reach high-risk youth who may struggle with truancy in secondary school [16] or who do not enroll in college (e.g., ~60% of college-age youth) [17].

Although data are lacking from clinical settings, such as the emergency department, researchers have identified longitudinal trajectories of sexual risk in broad populations of youth. These trajectories have been constructed using indices of different risk behavior measures (e.g., unprotected sex, multiple partners) collected across multiple time points, with groups described relative to each other (i.e., high vs. low-risk trajectories in the same sample) and in terms of how they change over time (e.g., decreasing, stable, increasing). For example, in a national sample of youth aged 15 to 25 surveyed annually from 1997 to 2005, Murphy and colleagues [18] used data about annual condom use and number of partners to identify four trajectories of sexual risk. The high-risk group was most common (42% of women; 39% of men); their sexual risk behaviors increased until age 21 and then decreased slightly, while still exhibiting the highest level of risk. The remaining trajectories were: decreasing risk (6% women; 12% men), increased risk (36% women; 34% men), and low risk (16% women; 15% men). The high-risk group had the most severe alcohol and marijuana use, with decreasing severity of substance use observed as sexual risk severity decreased in lower risk trajectories.

In another national sample of youth [19] aged 15 to 24 surveyed annually from 1998 to 2004, only three trajectories emerged: early-onset increasing (69%), mid-onset increasing (23%), and abstaining (9%). Joint trajectories were also identified with regard to alcohol use, sexual risk, and delinquency, with the most common joint trajectory (46%) indicating sex and alcohol use being initiated in early adolescence with increasing risk into emerging adulthood. These and similar studies [18–20] provide a foundation for understanding trajectories of sexual risk among the general population of young people, indicating that subgroups of youth who engage in more sexual risk behaviors over time are likely to also report other risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, delinquency).

However, as noted by Brookmeyer and Henrich [19], youth engaging in multiple risk behaviors (i.e., sexual risk behaviors and drug use or delinquency) may display unique trajectories of risk. For example, researchers have used national data collected over six years to demonstrate that youth with more severe alcohol and/or marijuana use had higher levels of delinquency and early and increasing sexual risk behaviors. Those in more high-risk delinquency trajectory groups were more likely to demonstrate early and increasing sexual risk behaviors [21]. However, research is needed among sub-populations who may be at highest risk for HIV and related health outcomes (e.g., Sexually Transmitted Infections [STIs]). For example, when examining overlapping risk trajectories for substance use, sexual behaviors, and conduct problems among low-income African American youth, Mustanski and colleagues [22] derived four specific trajectory groups. Most youth in their sample (74%) comprised a low-risk group, which showed low involvement in substance use and conduct problems, but youth in this group did exhibit increasing sexual risk across adolescent development. Further, the remaining 26% of youth comprised three other trajectory groups that showed, at times, increased levels of risk-taking compared to the low risk group. These trajectory groups were characterized by increasing, high-risk behaviors (12%), adolescent-limited involvement in risk behaviors (8%), or early experimentation (6%).

Another study of youth from urban, high-crime neighborhoods followed from ages 10 to 21 (1985 to 1996) found that alcohol and marijuana use had distinct relationships with number of sexual partners and unprotected sex over time [23]. Youth who were in chronic and late-onset binge drinking trajectories had more sexual partners at age 21 than non-binge drinkers. In addition, youth in a late-onset marijuana use trajectory also had more sexual partners and were more likely to use condoms inconsistently at age 21 than non-users of marijuana. Although these studies of at-risk youth are informative, additional studies of sexual risk trajectories among at-risk youth presenting to medical settings would provide data that are currently lacking to inform sexual risk reduction interventions for these settings. Furthermore, most examinations of general sexual risk trajectories took place before the more recent rise in HIV infections among youth, [1, 24] and may not capture generational differences in sexual risk behaviors.

Thus, we examined longitudinal trajectories of sexual HIV risk behaviors over two years by conducting secondary data analyses of a prospective cohort study that included a sample of drug-using adolescents and emerging adults attending an urban emergency department. Despite injection drug use (IDU) being an important mode of HIV transmission, in the present sample, we focused on sexual risk behaviors as the primary risk for HIV transmission because the rates of IDU in our sample were very low. Thus, at the time these youth were studied, they were at greater immediate risk for HIV transmission through sexual contact. These data provide novel information given that we include a more extensive and/or new measures in several areas, including: a) proximal sexual risk behaviors (e.g., past month unprotected anal sex, sex with unknown partners, transactional sex), b) substance use severity as opposed to frequency measures, c) baseline mental health characteristics, and d) relationship violence. Although we did not have specific hypotheses about the trajectories that we would find in these data, we hypothesized that those youth in trajectories demonstrating more frequent sexual risk behaviors over time would be characterized by more severe patterns of risk factors at baseline, including substance use, mental health, and relationship violence involvement.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

Data come from the Flint Youth Injury project (FYI; [25, 26]), a prospective cohort study of 14–24 year-old youth who presented for emergency care at the Hurley Medical Center Emergency Department (ED), a Level-1 trauma center in urban Flint, Michigan. FYI was designed to examine longitudinal differences in health service utilization and risk behaviors among drug-using adolescents and emerging adults who presented to the ED for an assault-related injury (injury group; per the CDC’s definition where confirmed or suspected assault injuries result from violence or physical force [26]) and those presenting for other reasons (comparison group). Specifically, the study sought to identify whether youth involved in violence (i.e., presenting for assault-related injury) had different service needs [25]. All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan and Hurley Medical Center and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Participant Recruitment

Recruitment procedures and participant characteristics are detailed in prior publications [25, 26]. Patients were recruited seven days per week, except on major holidays, from December 2009 through September 2011. Bachelor’s and Master’s-level Research Assistants (RAs) with backgrounds in psychology, social work, and related health fields recruited 24 hours per day from Thursday through Monday and from 5am until 2am on Tuesday and Wednesday (shortened times on these days due to lower patient volumes). Drug-using youth presenting for assault-related injury were over-sampled (N = 350) and a comparison group (N = 250) was recruited to be proportionally balanced with the injury group on gender and age range (14–17 years, 18–20 years, and 21–24 years).

Patients were identified for screening using the electronic health record system and approached in ED areas. We employed a systematic enrollment procedure to recruit patients into both groups. Individuals in the study age range who presented for assault-related injury were prioritized and approached first. When an individual with assault-related injury met inclusion criteria (e.g., drug use; see below), patients of the same gender and age range presenting for other reasons were approached for screening until an eligible patient in the comparison group met inclusion criteria (e.g., drug use). Primary exclusion criteria for screening included: presenting for acute sexual assault or suicidal ideation (requiring additional ED-based social services during the visit), insufficient cognition precluding informed consent, and not having a parent/guardian present (if under age 18). Assault-injured patients who were medically unstable due to trauma and admitted were approached for recruitment if they stabilized within three days.

For the assault-related injury group, we approached 849 individuals (84.6% screened) and for the comparison group we approached 846 individuals (86.3% screened). Patients reporting past six-month illicit drug use (marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, inhalants, hallucinogens, or street opioids) or misuse of a prescription drug (sedatives, stimulants, opioids) were eligible for the longitudinal study (N = 388 in the assault-related injury group and N = 278 in the comparison group). These drug use eligibility criteria were assessed using a computerized version of the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; [27, 28]) administered during screening.

After self-administering screening surveys (i.e., the ASSIST, demographics) on a tablet computer in ED treatment and waiting areas, patients who were eligible and provided written informed consent (or assent with parental consent for those under 18) completed a baseline assessment consisting of additional self-administered surveys and a semi-structured interview. Participants received a gift valuing $1.00 (e.g., pens, lip balm) for screening and $20 for baseline assessment. Follow-up assessments mirrored the baseline, and took place at community locations or the patient’s home. Compensation was as follows: $35 for 6-month, $40 for 12-month, $40 for 18-month, and $50 for 24-month follow-up.

Measures

Demographics and background characteristics

Items assessing several demographics were administered at screening/baseline and adapted from prior research. Participants self-reported their gender, current age, and school status [29] and, as an indicator of socio-economic status (SES), whether they or their parents received public assistance [30], in addition to number of children. Self-reported race was based on NIH guidelines [31] but, due to lack of variability, participants were separated into two categories (African American and Other) for analyses. Also due to lack of variability of responses assessing marital status [32, 33], participants were characterized as married, living with a partner, or never married/widowed/separated/divorced. At baseline and the 24-month follow-up appointment, participants were offered a saliva-based HIV antibody test (OraQuick Advance Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test, OraSure Technologies, Inc., Bethlehem, PA). Participants received pre-test counseling by reviewing an HIV information brochure and were provided results of their tests. In the event of a positive test, a second test was conducted and participants were counseled to seek confirmatory testing.

Substance Use

Baseline past 6-month drug use was assessed by the ASSIST [27, 28] as described above. Marijuana was by far the most commonly used drug (97.2% in past 6 months); therefore, for these analyses, we included participants’ severity scores on the marijuana subscale of the ASSIST. Scores in the range 0–3 are considered lower risk, 4–26 are moderate risk, and 27 or higher is high risk; internal consistency in the present sample was α=.70. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C; [34]) total score was used at baseline to measure severity of alcohol use; the item measuring binge drinking queried episodes of 5 drinks or more, rather than 6 drinks or more based on prior work [35]. Possible AUDIT scores range from 0 to 12, with higher scores reflecting more severe alcohol use; internal consistency in the present sample was α=.86. Lifetime injection drug use [27, 28] was asked at baseline and past-month injection drug use [36, 37] was assessed at each time point.

Sexual risk behaviors

At baseline, participants who reported lifetime sexual intercourse [38] received eight additional questions about recent sexual behaviors. All items were coded yes/no (1, 0) for analyses to reflect any risk. First, using four items adapted from the HIV Risk-Taking Behaviour Scale [36, 37], participants reported number of sexual partners (≥2 partners was coded as yes =1 to reflect the risk associated with multiple partners, and 0 or 1 partners was coded no = 0), unprotected sex with regular partners, unprotected sex with casual partners (described as “casual partners [acquaintances]” for participants), and unprotected anal sex for the past month. One item adapted from AddHealth [30] queried past-month exchanging sex for money or drugs (coded 1 = yes, 0 = no). Two items assessing past-month exchanging sex for food/shelter and sex with an unknown partner (i.e., “someone you did not know and were not planning on seeing again”) were created for use in this study (coded 1 = yes, 0 = no). Another item was adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey [39] to assess whether alcohol or drugs were used prior to the last event of sexual intercourse (coded 1= yes, 0 = no). These eight items were repeated at each follow-up assessment. Similar to prior research [40, 41], we created a composite of sexual risk measures by totaling the number of items on which the participant indicated any risk behavior (composite scores range from 0 to 8) at each assessment. Participants who reported no history of sexual intercourse at each follow-up received a score of 0.

Mental health

Past-week symptoms of depression and anxiety were measured at baseline with selected subscales from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; [42, 43]). Participants rated how much (from not at all to extremely) they were bothered by six anxiety symptoms and six depression symptoms. Scores on each subscale were summed, ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Internal consistency in our sample was α=.87 for depression and α=.88 for anxiety items. At baseline, RAs who were trained by the Co-investigators administered modules of The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and the MINI-KID (version 6.0, 1/1/10; [44, 45]) to assess diagnostic criteria for antisocial personality (for ages 18 or older) and conduct disorders (for ages under 18). Participants were coded as either meeting or not meeting criteria for a current diagnosis of antisocial personality or conduct disorder (α = .83 for MINI-KID, n = 89; α = .78 for MINI, n = 487).

Relationship violence involvement

Involvement in dating/relationship violence during the six months prior to baseline was assessed with revised items from the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 [46]. Using 26 items (13 reflecting aggression, 13 reflecting victimization), participants reported whether violent behaviors occurred with their “dating partner (girlfriend/boyfriend, fiancé, husband/wife).” Given the reciprocal nature of dating violence victimization and perpetration [47–49], for the current analyses, items were collapsed to reflect any involvement (aggression or victimization) in relationship violence.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, proportions) were calculated for demographics and variables of interest. Group-based trajectory modeling was used to examine patterns of sexual risk behaviors over time. The method assumes individuals belong to one of a number of unobservable groups, and their group membership determines the response distribution at each time point; the inferential targets are the number of groups, and the trajectory structure within each group. Trajectory structures were restricted to linear, quadratic, or cubic, and the censored normal distribution was employed due to the bounded nature of the outcome variable. Polynomial degree was selected by sequential deletion (cubic, then quadratic, etc.) until the leading term was statistically significant. Age, gender, and initial ED presentation reason (assault-related injury, other reason) were included as time-stable covariates. Following prior recommendations [50–52], we examined the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and considered parsimony in selecting the optimal trajectories. To evaluate class separation, we calculated average posterior probabilities and entropy for the derived trajectory solution. For subsequent analyses, individuals were assigned to groups based on maximum posterior probability. Bivariate analyses (ANOVAs, Chi-Square tests) were used to examine how trajectory groups differed on baseline characteristics (demographics, alcohol and marijuana use severity, dating violence, mental health), controlling for gender, age group, and baseline ED presentation reason.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

At study enrollment, participants comprised 350 youth presenting for assault-related injury and 250 youth presenting for other reasons (additional sample details can be found in prior articles [25, 53]). For the purpose of the current analyses, we excluded individuals who reported being married at baseline (n = 24; 13 from the assault-related injury group). Across all 576 participants, the mean age was 20.0 years (SD = 2.4) and 41.2% were female. Over half (59.6%) of participants were African American and 40.5% were of European American or other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Only 25.4% were living with a partner; nearly all (94.6%) reported lifetime sexual activity and 39.2% had at least one child. Regarding sexual orientation, 94.7% of sexually active men reported their lifetime sexual partners were “all female” and 76.0% of sexually active females reported their lifetime sexual partners were “all male” As an indicator of socioeconomic status, 72.7% of the sample reported that they or their parents received public assistance.

Regarding their substance use history, 97.2% of participants reported marijuana use in the 6 months prior to baseline. Misuse of prescription sedatives (11.3%) and prescription opioids (9.9%) occurred next most frequently; all other substances assessed with the ASSIST were used by fewer than 6% of the sample. At baseline, 3.3% (n = 19) reported lifetime injection drug use; past-month injection drug use was even more infrequent with 1.4% (n = 8) reporting injection drug use.

At baseline, 562 participants agreed to HIV testing. Results indicated that all tests were negative except for one, which was inconclusive. At 24-month follow-up, 418 participants agreed to HIV testing, with all participants testing negative with the exception of two inconclusive results and one positive result. Injection drug use remained infrequent over time, with 7 or fewer participants reporting injection at each follow-up assessment. Thus, given the low frequency of positive HIV test results and self-reported injection drug use, these variables were not included in analyses of sexual risk behavior trajectories.

Sex Risk Behaviors at Baseline

Among the 8 sexual risk behaviors assessed, the most commonly reported risk behavior was unprotected sex with a regular partner (54.0%) in the month preceding baseline. Consuming alcohol or drugs prior to most recent sexual intercourse (34.2%), past-month multiple partners (30.6%), and past-month unprotected sex with casual partners (27.1%) were the next most commonly reported behaviors. Other past-month risk behaviors were reported by fewer than 20% of the sample, including sex with an unknown partner (16.5%), unprotected anal sex (7.6%), exchanging sex for money/drugs (5.0%), and exchanging sex for food/shelter (3.8%).

Sexual Risk Behavior Trajectories

To select the number of groups, we examined the BIC for one, two, three, and four-group solutions (shown in Table I). For the three-group solution, there was a decrease in BIC relative to the two-group solution, but the four-group solution demonstrated an increase in BIC, supporting the three-group solution. Linear trajectories were deemed sufficient for all groups. Average posterior probabilities for the final solution were .85 for group 1, .87 for group 2, and .85 for group 3 with relative entropy = .71.

Table I.

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for trajectory solutions

| Number of trajectory groups | BIC |

|---|---|

| 1 | 4326.15 |

| 2 | 4205.78 |

| 3 | 4177.88 |

| 4 | 4180.30 |

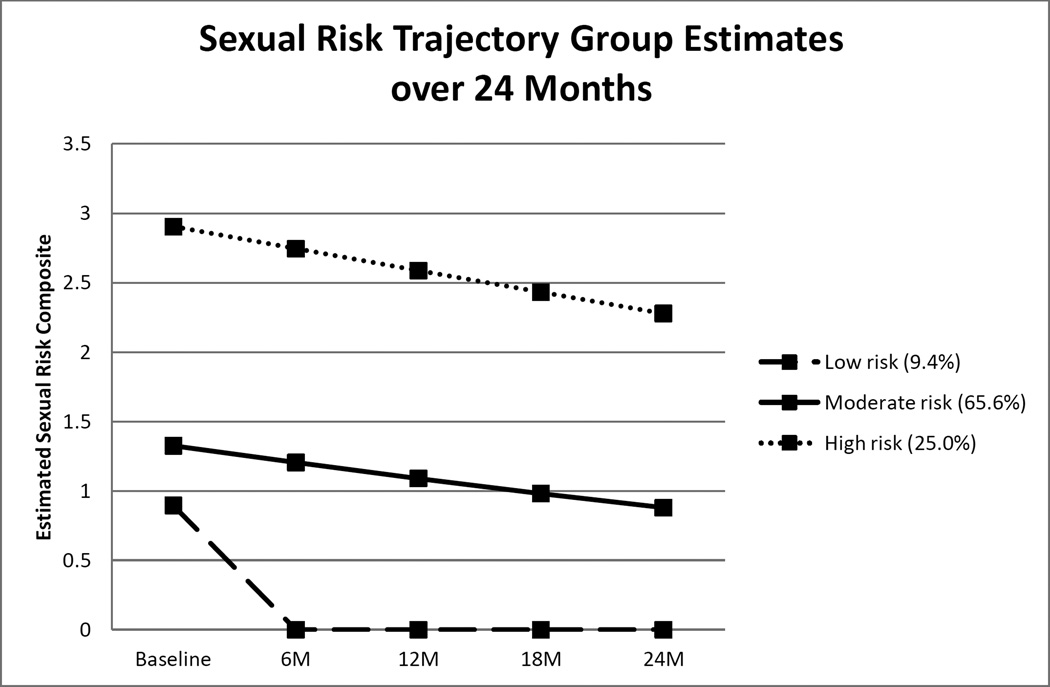

As shown in Figure 1 which depicts estimated values, 9.4% (N = 54) participants were in group 1, described as a low-risk group that was characterized by estimates reflecting low to no involvement in sexual risk behaviors over two years. After the initial ED visit, trajectory estimates suggest that youth in this group avoided most, if not all, sexual risk behaviors assessed. The majority of the sample (65.6%, N = 378) comprised group 2, which is a moderate-risk group characterized by some involvement in sexual risk behaviors over two years that appears to decline slightly. One-quarter (25.0%, N = 144) of participants comprised group 3, a high-risk group that consistently engaged in more sexual risk behaviors than groups 1 and 2; however, the high-risk group’s involvement in sexual risk behaviors is also shown to decline somewhat over the two year period. Table II displays the demographic characteristics of participants in each trajectory group.

Figure 1.

Trajectory groups’ estimated scores on the sexual risk composite measure at each time point

Table II.

Baseline characteristics by trajectory group

| Low Risk (N = 54) % or M (SD) |

Moderate Risk (N = 378) % or M (SD) |

High Risk (N = 144) % or M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male (vs. female) | 63.0% | 58.2% | 59.0% |

| African American (vs. Caucasian and other)* | 61.1% | 56.1% | 68.2% |

| Age | 19.5 (2.7) | 20.2 (2.4) | 20.2 (2.3) |

| Live With a Partner (vs. Not) | 18.5% | 26.2% | 25.7% |

| Receipt of public assistance | 74.1% | 71.4% | 75.7% |

| ED visit for assault-related injury at baseline* | 55.6% | 57.7% | 61.8% |

| Substance Use | |||

| Alcohol severity score***a,b,c | 2.3 (4.0) | 4.1 (5.8) | 7.3 (8.5) |

| Marijuana severity score***a, c | 12.1 (8.8) | 12.4 (8.7) | 15.9 (9.1) |

| Mental health and violence | |||

| Dating violence involvement*** | 68.5% | 57.7% | 76.4% |

| Anxiety symptoms***c | 4.4 (6.1) | 3.6 (4.7) | 5.5 (6.0) |

| Depression symptoms**a,c | 3.4 (5.0) | 4.3 (5.1) | 5.8 (5.7) |

| Antisocial/conduct disorder*** | 13.0% | 18.0% | 35.4% |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p <.001

High group > Low group

Moderate group > Low group

High group > Moderate Group

Results of follow-up analyses identified several differences between trajectory groups on baseline characteristics when controlling for gender, age group, and baseline ED presentation reason. Regarding demographics, as shown in Table II, somewhat fewer African American individuals comprised the moderate group (56.1%) versus the low and high groups (61.1% and 68.2%, respectively). The proportion of individuals presenting to the ED at baseline for assault-related injury was also significantly different across the groups, ranging from 55.6% in the low group to 61.8% in the high group. We did not find differences between trajectory groups on gender, age, living with a partner (vs. not), or receipt of public assistance. The high group had the most severe pattern of substance use at baseline; both alcohol and marijuana severity were significantly higher among this group compared to the low and moderate groups. The moderate group also had significantly higher alcohol use severity than the low group. Regarding mental health, the high group had significantly higher scores on the measure of depression symptoms compared to the other groups, but the only difference on the anxiety measure occurred between the high and moderate group. Relationship violence involvement and antisocial personality/conduct disorder symptoms were both most frequently endorsed among the high group.

DISCUSSION

The current analyses begin to address a critical gap in the literature with regard to the sexual risk trajectories of high-risk youth engaged at a clinical setting. Prior research has not focused on drug-using youth who may be at higher risk for contracting HIV and has not typically followed youth who seeking clinical care, where they could receive interventions to disrupt future risk trajectories. When using an 8-item index of sexual risk behaviors, the present findings identified three separate trajectories of sexual risk behaviors among urban, drug-using youth aged 14 to 24 followed for two years. Almost 10% of youth maintained little to no involvement in sexual risk over time. The majority of the sample (65.6%) fell into a group with slightly more involvement in sexual risk behaviors over time; these youth may be displaying a normative pattern of sexual risk, given their developmental stage. Perhaps more concerning is that 25.0% of individuals were in the high group. This group reported an average of 2.8 sexual risk behaviors in the month before baseline and still an average of 2.2 sexual risk behaviors two years later, which is more than twice that reported by the moderate group. Each group appeared to decline somewhat over time, which may reflect the known developmental peak in sexual risk-taking that occurs in early adulthood [6–8]; however, as these youth were only followed for two years, it is not clear whether these reductions are maintained over time. The high-risk youth also tended to have the most severe profile of psychosocial risks at baseline, including marijuana and alcohol use, dating violence involvement, and mental health symptoms. This increased severity suggests that targeted, multi-level early interventions that address multiple psychosocial factors (e.g., violence, substance use, mental health) may help deter the sexual risk trajectories of individuals in the highest risk group. For example, such interventions might be effective if they combine resources for case management with access to social services (e.g., domestic violence services) and mental health services (e.g., medications, psychological therapy). Urban emergency departments, where many high-risk youth seek healthcare, may play a critical role in facilitating linkages to such resources.

Similar to prior studies [18, 22], we have identified varying degrees of severity in trajectories of sexual risk among youth. Unlike national data collected over longer time periods [18, 20], only three groups emerged in our sample and they all tended to decline in risk involvement over time. Consistent with Guo and colleagues [23], who found developmental differences in substance use initiation were associated with sexual risk at age 21, we also found that marijuana and alcohol use, and in particular severity of use, predicted sexual risk over time. It is important to note that the focus of our study on drug-using youth likely affected the trajectories identified. Our current analyses, however, extend beyond prior research in that we included a composite measure of several sexual risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected anal sex, transactional sex, sex with unknown partners) that have not been included in prior examinations of longitudinal trajectories, particularly among substance-using youth. Accounting for behaviors such as transactional sex and sex with unknown partners provides a more comprehensive assessment of the constellation of risky behaviors related to sex that can contribute to the transmission of HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Due to the disinhibiting effects of substances, such high-risk behaviors may more frequently occur in substance-using samples than general samples of youth, and thus may need to be considered in developing and tailoring interventions for this population. In particular, although incidence of HIV in our sample was low over time, such risk profiles are also reflective of risk for STIs, which also have significant morbidity [54–58].

Despite the inclusion of mental health symptoms and relationship violence in socio-ecological models [13, 14] of HIV risk, prior research has also not examined these constructs as markers of sexual risk trajectories over time among youth. The present findings underscore the importance of these factors and are consistent with prior research using other methodologies [59–62]. Our finding that drug-using youth in the higher risk trajectory had more severe mental health symptoms suggests that future research should expand this area to investigate additional mental health conditions (e.g., PTSD, bipolar illnesses) in relation to trajectories of sexual risk. Research is also needed to examine mechanisms of influence between relationship violence and sexual risk behavior, given that most individuals in the highest risk trajectory were involved in relationship violence. There is evidence that women in violent relationships experience higher rates of unintended pregnancy and STIs, and that higher severity and frequency of violence is associated with greater health consequences [63].

Our results suggest that interventions to alter sexual risk trajectories may be enhanced by addressing mental health and relationship violence involvement. Tailored interventions may be necessary depending on which risk factors are present at baseline. For example, depending on baseline characteristics, an intervention could include content related to coping skills for managing depression and anxiety, anger management, communication strategies, and coping skills for those involved in relationship violence, along with referrals to specialty treatment or resources for those with more severe symptoms or problems. While these youth were recruited from an emergency department setting, where initial brief interventions for substance use and risky behaviors may lead to reductions in risk behaviors [64–67], extended, multi-pronged, and/or community-oriented approaches may be necessary to address more pervasive factors (e.g., lack of housing or food potentially leading to transactional sex) that can influence and/or co-occur with risky behaviors over time. Future studies should develop and evaluate the impact of such interventions on altering behavioral trajectories longitudinally. Examining how these trajectories predict future sexual and drug use-related outcomes would also aid in further refinement of targeted interventions. Prevention of injection drug use remains an important area of concern with drug-using youth; however, we did not include this in our analyses due to our focus on sexual risk and the low base rates of injection drug use in our sample over time.

Despite these implications, findings should be interpreted in light of the present study’s limitations. A potential limitation includes the reliance on retrospective self-report data, though we used procedures that encourage accurate reporting (e.g., assuring confidentiality, obtaining a Certificate of Confidentiality, computerized measures completed in private). The generalizability of our results to other youth in different settings or geographic locations is another limitation. While these data do not represent all youth, urban, drug-using youth are an important risk group to study given current epidemiological trends in HIV transmission. Nonetheless, replication is required in order to identify whether these trajectories are distinct or whether others may emerge. Analytically, the wide age range of our sample prohibited us from structuring the data by age, but we were able to include age in our analyses as a control variable. However, this approach does not identify distinct age-related trajectories, which limits comparability to other trajectories identified in youth [41].

Although we excluded married individuals from analyses, estimates of sexual risk behaviors could be over-estimated due to the fact that a small portion of our sample reported living with a partner. Presumably, some of the sexual risk behaviors measured may not be as risky in the context of a long-term, committed monogamous sexual partnership where partners may be either attempting to have children, thus not using condoms, or using other forms of birth control. We note that, in our study, most individuals in our sample were not in such partnerships and there were many participants with both multiple partners and unprotected sex during a brief one-month period across time points (e.g., at baseline, 16% of cohabiting individuals had multiple partners in the previous month prior and 30% had sex without a condom with a casual partner). We are also limited in that we did not ask participants to report on the HIV status of their cohabiting partners, nor do we have reliable information on their partner’s sexual risk behaviors; thus, we are missing information that might better characterize partnered participants’ risk profiles. Finally, our index of sexual risk behaviors is limited by potential overlap in behaviors measured because data are not event-specific, which is a limitation of the literature in this area (for example: [18, 22]). Future studies are needed using daily process methodology to obtain data on discrete sexual risk behaviors to aid in understanding behavioral trajectories.

Despite these limitations, our study provides new information on trajectories of sexual risk among urban, drug-using youth which can help inform intervention development and future research to prevent HIV and STI transmission. At baseline, youth in the highest risk trajectory had the most severe profile of mental health symptoms, substance abuse, and relationship violence involvement - all factors which can presumably complicate care for HIV and STIs. Future research is needed to evaluate overlapping risk trajectories and determine the most effective interventions for altering the trajectory of sexual risk behaviors to prevent future HIV and STI transmission in youth, in addition to other psychosocial sequelae of risky behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 #024646). The first author was supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23 #036008) during her work on this project. Center support was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U01CE001957). The authors wish to acknowledge statistical support from Ms. Linping Duan, the FYI study staff, and the patients and staff at the Hurley Medical Center.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Informed Consent: Informed consent (or assent with parental consent for those under 18) was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. 2013;25 [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth. 2015 [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/index.html.

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS in the United States by Geographic Distribution. 2015 [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/geographicdistribution.html.

- 4.Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance us ein emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):235–253. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav. 2012;37(7):747–775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett JJ. Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Dev Rev. 1992;12:339–373. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dariotis JK, Sonenstein FL, Gates GJ, et al. Changes in sexual risk behavior as young men transition to adulthood. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(4):218–225. doi: 10.1363/4021808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. NSDUH Series H-41 (SMA) 11–4658. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessor R. Problem behavior and developmental transition in adolescence. J Sch Health. 1982;52(5):295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1982.tb04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geier CF. Adolescent cognitive control and reward processing: implications for risk taking and substance use. Horm Behav. 2013;64(2):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell MR, Potenza MN. Addictions and Personality Traits: Impulsivity and Related Constructs. Current behavioral neuroscience reports. 2014;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40473-013-0001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voisin DR, Jenkins EJ, Takahashi L. Toward a conceptual model linking community violence exposure to HIV-related risk behaviors among adolescents: directions for research. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Rosenthal SL. Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the importance of a socio-ecological perspective--a commentary. Public Health. 2005;119(9):825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Chen M, Tolley EE. School-based interventions for improving contraceptive use in adolescents. The Cochrane Library. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallfors D, Cho H, Brodish PH, Flewelling R, Khatapoush S. Identifying high school students “at risk” for substance use and other behavioral problems: Implications for prevention. Substance use & misuse. 2006;41(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/10826080500318509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Commerce CB, American Community Survey (ACS), 2009 and 2014. Percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions and percentage distribution of those enrolled, by sex, race/ethnicity, and selected racial/ethnic subgroups: 2009 and 2014. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy DA, Brecht ML, Herbeck DM, Huang D. Trajectories of HIV risk behavior from age 15 to 25 in the national longitudinal survey of youth sample. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(9):1226–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC. Disentangling adolescent pathways of sexual risk taking. J Prim Prev. 2009;30(6):677–696. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang DY, Murphy DA, Hser Y-I. Developmental trajectory of sexual risk behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. Youth & society. 2012;44(4):479–499. doi: 10.1177/0044118X11406747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang DY, Lanza HI, Murphy DA, Hser Y-I. Parallel development of risk behaviors in adolescence: Potential pathways to co-occurrence. International journal of behavioral development. 2012;36(4):247–257. doi: 10.1177/0165025412442870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustanski B, Byck GR, Dymnicki A, Sterrett E, Henry D, Bolland J. Trajectories of multiple adolescent health risk behaviors in a low-income African American population. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(4 Pt 1):1155–1169. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo J, Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):354–362. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. 2011;21 [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohnert KM, Walton MA, Ranney M, et al. Understanding the service needs of assault-injured, drug-using youth presenting for care in an urban Emergency Department. Addict Behav. 2015;41:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham RM, Carter PM, Ranney M, et al. Violent reinjury and mortality among youth seeking emergency department care for assault-related injury: a 2-year prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):63–70. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103(6):1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study--Adolescent (DATOS-A), 1993–1995: [United States] [Computer file] Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design: Carolina Population Center. University of North Carolina; 1997. [updated 3/23/2005]. Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute of Health. NIH POLICY ON REPORTING RACE AND ETHNICITY DATA: SUBJECTS IN CLINICAL RESEARCH. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith G, Ross R, Rost K. Psychiatric outcomes module: Substance abuse outcomes module (SAOM) In: Sedere LI, Dickey B, editors. Outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith GR, Burnam MA, Mosley CL, Hollenberg JA, Mancino M, Grimes W. Reliability and validity of the substance abuse outcomes module. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders identification Test (AUDIT):WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Spirito A, Monti PM. Screening adolescents for problem drinking: performance of brief screens against DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(4):579–587. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, Wodak A. The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. AIDS. 1991;5(2):181–185. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward J, Darke S, Hall W. The HIV Risk-Taking Behavior Scale (HRBS) Manual. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Zapert KM, Maton KI. A longitudinal study of stress-buffering effects for urban African American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(1):17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. National High School Questionnaire. 2009 [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/questionnaire_rationale.htm.

- 40.Mustanski B. Ethical and regulatory issues with conducting sexuality research with LGBT adolescents: A call to action for a scientifically informed approach. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(4):673–686. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy DA, Brecht ML, Huang D, Herbeck DM. Trajectories of Delinquency from Age 14 to 23 in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Sample. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2012;17(1):47–62. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2011.649401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derogatis LR, Spencer MS. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, scoring, and procedures manual-1. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID) J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):313–326. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rothman EF, Stuart GL, Greenbaum PE, et al. Drinking style and dating violence in a sample of urban, alcohol-using youth. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2011;72(4):555–566. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swahn MH, Alemdar M, Whitaker DJ. Nonreciprocal and Reciprocal Dating Violence and Injury Occurrence among Urban Youth. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2010;11(3):264–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Testa M, Hoffman JH, Leonard KE. Female intimate partner violence perpetration: stability and predictors of mutual and nonmutual aggression across the first year of college. Aggressive behavior. 2011;37(4):362–373. doi: 10.1002/ab.20391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological methods & research. 2001;29(3):374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural equation modeling. 2007;14(4):535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonar E, Whiteside LK, Walton MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV risk among adolescents and young adults reporting drug use: Data from an urban Emergency Department in the U.S. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. In Press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bishop-Townshend V. STDs: screening, therapy, and long-term implications for the adolescent patient. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1996;41(2):109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manavi K. A review on infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;20(6):941–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paavonen J. Sexually transmitted chlamydial infections and subfertility. International Congress Series. 2004;1266:277–286. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tiller CM. Chlamydia during pregnancy: Implications and impact on perinatal and neonatal outcomes. JOGNN. 2002;31:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunningham KA, Beagley KW. Male genital tract chlamydial infection: Implications for pathology and infertility. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:180–189. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Howard DE, Debnam KJ, Wang MQ. Ten-year trends in physical dating violence victimization among U.S. adolescent females. J Sch Health. 2013;83(6):389–399. doi: 10.1111/josh.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howard DE, Debnam KJ, Wang MQ, Gilchrist B. 10-year trends in physical dating violence victimization among US adolescent males. International quarterly of community health education. 2012;32(4):283–305. doi: 10.2190/IQ.32.4.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown LK, Tolou-Shams M, Lescano C, et al. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of sexual risk among African American adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):444.e1–444.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, et al. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108(5):E85. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8(2):149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Newton AS, Dong K, Mabood N, et al. Brief emergency department interventions for youth who use alcohol and other drugs: a systematic review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):673–684. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828ed325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, et al. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(8):890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]