Abstract

In the blooming field of on-surface synthesis, molecular building blocks are designed to self-assemble and covalently couple directly on a well-defined surface, thus allowing the exploration of unusual reaction pathways and the production of specific compounds in mild conditions. Here we report on the creation of functionalized organic nanoribbons on the Ag(110) surface. C–H bond activation and homo-coupling of the precursors is achieved upon thermal activation. The anisotropic substrate acts as an efficient template fostering the alignment of the nanoribbons, up to the full monolayer regime. The length of the nanoribbons can be sequentially increased by controlling the annealing temperature, from dimers to a maximum length of about 10 nm, limited by epitaxial stress. The different structures are characterized by room-temperature scanning tunnelling microscopy. Distinct signatures of the covalent coupling are measured with high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy, as supported by density functional theory calculations.

On-surface synthesis, in which molecular units assemble and couple on a defined surface, can access rare reaction pathways and products. Here, the authors synthesize functionalized organic nanoribbons on the Ag(110) surface, and monitor the evolution of the covalent reactions by an unorthodox vibrational spectroscopy approach.

The emerging field of on-surface synthesis aims at producing novel and original reactions templated on the surface of a well-defined metal substrate1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. The latter can be catalytically active and compels the confinement of the molecular precursors upon adsorption, allowing for the exploration of new reaction pathways in soft conditions. Robust covalent nanostructures can thus form directly on surfaces by combining supramolecular self-assembly processes with chemical activation. After exfoliation process, integration of the organic structures into electronic devices is envisioned, whereby exquisite and steerable properties are expected for a wide range of applications10,11,12. The on-surface synthesis strategy can lead, for example, to soft linear polymerization of alkyl chains13,14 or to the formation of well-defined extended nanoribbons15,16,17. A large variety of reactions has been explored to activate the formation of covalent bonds between instructed molecular building-blocks. Nevertheless, the community is still looking for a robust rationale before being able to effectively control and further develop this technological field. In fact, despite nearly a decade of successful demonstrations of on-surface covalent coupling, the choice and availability of efficient systems is still limited. For example, Ullmann coupling on surfaces is a very popular C–C coupling technique3,18,19 but has important drawbacks: atomic halogens are produced as byproducts impeding the coupling process20, and the high reactivity of the radical intermediates leads to the competitive formation of organometallics21,22. More recently, coupling of alkyne moieties has been demonstrated, but because it is non-specific, the on-surface reaction leads to the concomitant formation of a variety of chemical species23. Also, introducing specific functionalization into the as-formed covalent nanostructures while preserving the reactivity of the precursors is not straightforward24,25,26,27. Finally, and most importantly, non-ambiguous demonstration of the covalent nature of the structures is always challenging21,28,29,30. This is usually done through direct observation and measurement of the spatial extension by scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM)21 or by high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging31. Chemical characterization can be fulfilled using scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS)28,32 or photoemission spectroscopy (XPS/UPS)33,34,35,36,37 but the correct interpretation of the experimental data normally requires the development of advanced and extensive theoretical modelling.

High-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy (HREELS) is one of the most advanced spectroscopy technique mainly used to obtain the vibrational signature of surface and adsorbate species. By assigning the vibrational modes, it is possible to evidence the chemical bonding between surface and adsorbate, between several adsorbates, or any chemical modification upon stimulation38,39,40,41.

The polycondensation of small aromatics containing oxygen is an appealing class of reactions for the creation of extended on-surface networks as it releases only harmless byproducts upon C–C coupling but it has been only scarcely and recently reported: the cyclotrimerization of acetyls42, the aldol condensation43, the reductive coupling of aldehydes44, and the ortho C–H functionalization of phenol derivatives45. The molecule s-indacene-1,3,5,7(2H,6H)-tetrone (also named ‘Janus dione'46 or in the following work, INDO4) belongs to the family of indanone derivatives. These compounds have been extensively studied in the literature, especially for the design of highly soluble planar heptacyclic polyarene structures (10,15-dihydro-5H-diindeno[1,2-a;1′,2′-c]fluorene), more commonly known as truxenes, that result from the trimerization of three indan-1-one units47. By increasing the content of ketone units per trimerizable units, similarly trimerization of indanedione derivatives can furnish truxenone analogues with three keto groups at the inner positions48. While generating symmetrical units such as in the case of INDO4, bifunctional tetraketoindacenes open the way towards carbonyl-functionalized microporous ladder polymers49.

In this report we present a covalent coupling mechanism for the polycondensation of the simple INDO4 precursor to form 1D functionalized nanoribbons. Dihydrogen is formed as byproduct, and the ketone functions are retained into the structures, thus preserving their functionality. Remarkably, we show that the surface-supported covalent coupling can be characterized by vibrational spectroscopy. The use of the surface-sensitive HREELS is here demonstrated as a unique and efficient tool to monitor in situ the covalent character of surface-supported transformations, positioning it as a promising technique for the field of on-surface synthesis. Upon deposition of INDO4 on the well-defined Ag(110) surface, extended supramolecular networks are observed. The cohesion is ensured by a dense network of hydrogen bonds, thanks to the presence of peripheral ketone groups and hydrogen atoms. C–H bond activation and homo-coupling of the precursors is achieved by thermal activation. For an annealing temperature of 300 °C, the anisotropic substrate acts as an efficient template fostering the formation and the alignment of covalent nanoribbons along the [001] direction. The length of the ribbons is limited to two to three monomeric units and is gradually increasing with increasing annealing temperature. A supplemental coupling mechanism is activated at higher temperatures (≥400 °C) producing longer transverse nanoribbons. The different structures are characterized by room-temperature STM. Distinct signatures of the covalent coupling are measured with HREELS by observing the stretching mode of the as-formed C=C bond between precursors in addition to the appearance of an exalted macrocycle-breathing mode, as supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Results

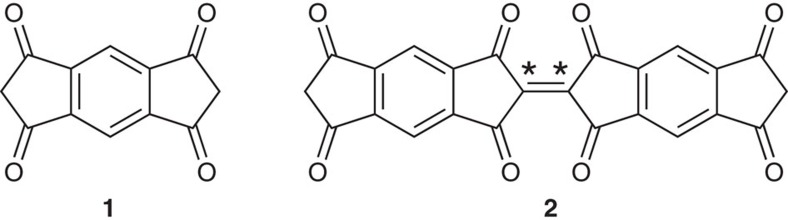

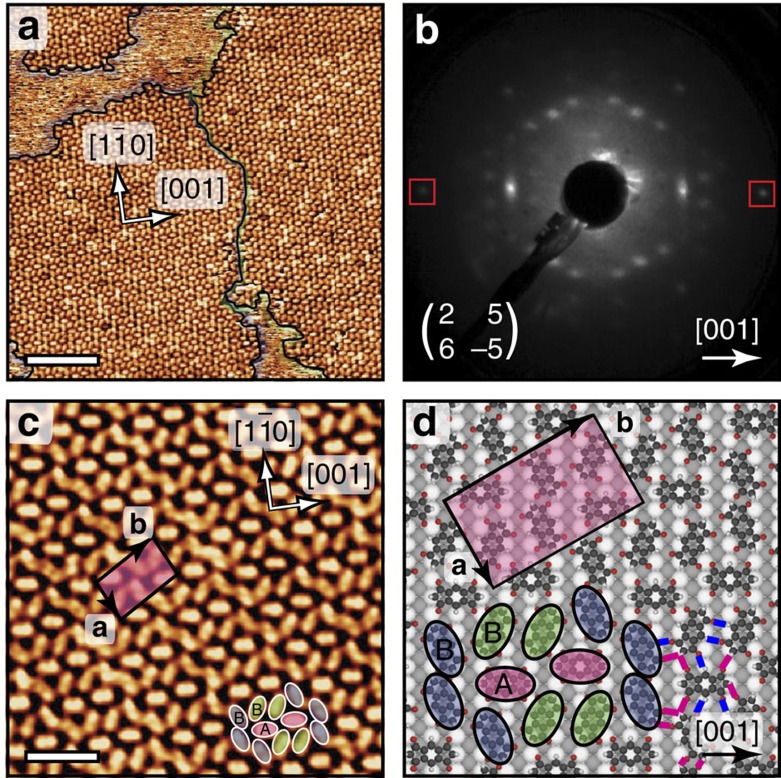

Supramolecular phase

The INDO4 molecule46 (1, Fig. 1) consists of a s-indacene core whereby each five-membered ring is composed of two carbonyl groups (at the 1,3,5,7-positions) and one CH2 (at the 2,6-positions). The sub-monolayer deposition of this molecule on Ag(110) surface (Supplementary Fig. 1) kept at room temperature leads to the formation of small domains poorly ordered (Supplementary Fig. 2) whereby the intermolecular cohesion is ensured by a dense network of hydrogen bonds50,51,52. The subsequent surface annealing or direct molecule deposition on a substrate held at a slightly elevated temperature (50 °C) fosters the growth of extended two-dimensional (2D) highly ordered molecular islands with two chiral domains, as shown in the large-scale STM image and corresponding low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) pattern of Fig. 2a,b, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). This close-packed structure appears as a complex pattern whereby two [001]-oriented molecules (type A, see pink ovals in Fig. 2c) are encapsulated in elongated 10-membered cavities (with type B molecules, see blue and green ovals in Fig. 2c). The unit cell of this molecular assembly comprises 6 molecules of three distinct orientations and corresponds to a commensurate (2 5; 6 -5) superstructure with respect to the Ag(110) surface. The tentative model of the tiling pattern as shown in Fig. 2d was derived from superimposing carefully scaled ball-and-stick models of INDO4 onto the experimental STM images, and subsequently placed on the space-filled model of the silver surface. This routine allows not only identifying the observed assembly and azimuthal orientations of the molecules, but also provides hints on their intended adsorption sites and intermolecular interactions. The model thus indicates an adsorption configuration of the type A molecules with their phenyl ring being most probably in the on-top site of the first Ag layer, and with their long axes being aligned with the [001] direction. In such configuration, all O atoms would be also lying close to on-top sites of Ag substrate, as it is also observed for other molecules53. The remaining type B molecules have two different symmetric orientations rotated by ±25° with respect to [1 0] directions, see green and blue ovals in Fig. 2c,d.

0] directions, see green and blue ovals in Fig. 2c,d.

Figure 1. INDO4 molecule.

Schematic representation of s-indacene-1,3,5,7(2H,6H)-tetrone (INDO4, 1)46 and related dimer (2).

Figure 2. Supramolecular phase.

Self-assembled structures formed by INDO4 upon adsorption on a Ag(110) surface held at 50 °C. (a) Large-scale scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image showing 2D molecular islands of opposite chirality highlighted by violet and green contours and (b) corresponding low-energy electron diffraction pattern (recorded at 17.3 eV) with Ag spots marked by the square outlines. (c) High-resolution STM image and (d) corresponding tentative model of the superstructure with rectangular unit cell and lattice directions indicated. Ag atoms in the topmost close-packed rows are shown white, while lower lying Ag atoms are grey. The formation of C=O···HC intermolecular hydrogen-bonding is indicated by blue and pink lines. Scale bars (a) 10 nm; (c) 3 nm.

Careful inspection of island perimeters and vacancy defects within this structure was performed to extract the most energetically favourable adsorption site. The molecular islands are preferentially terminated by type A [001]-oriented INDO4 molecules, while the defects in island interiors are mainly found for type B molecules (Supplementary Fig. 4). Therefore one can conclude that the [001]-oriented (type A) molecules are more stable with possibly stronger surface interaction. The presence of two distinct adsorption sites A and B in this assembly is additionally confirmed by the difference in molecular contrast. Specifically, the backbones of type A and type B molecules can be visualized in STM images as oval-shaped dim and bright protrusions, respectively, or occasionally in a reverse way due to the change of tip condition (see Supplementary Fig. 5). The distances of 2.6±0.1 and 2.7±0.2 Å between O and H atoms of neighbouring molecules derived from the tentative model in Fig. 2d indicate that the stability of such complex structure is further enhanced by the formation of C=O···HC intermolecular hydrogen bonds54,55.

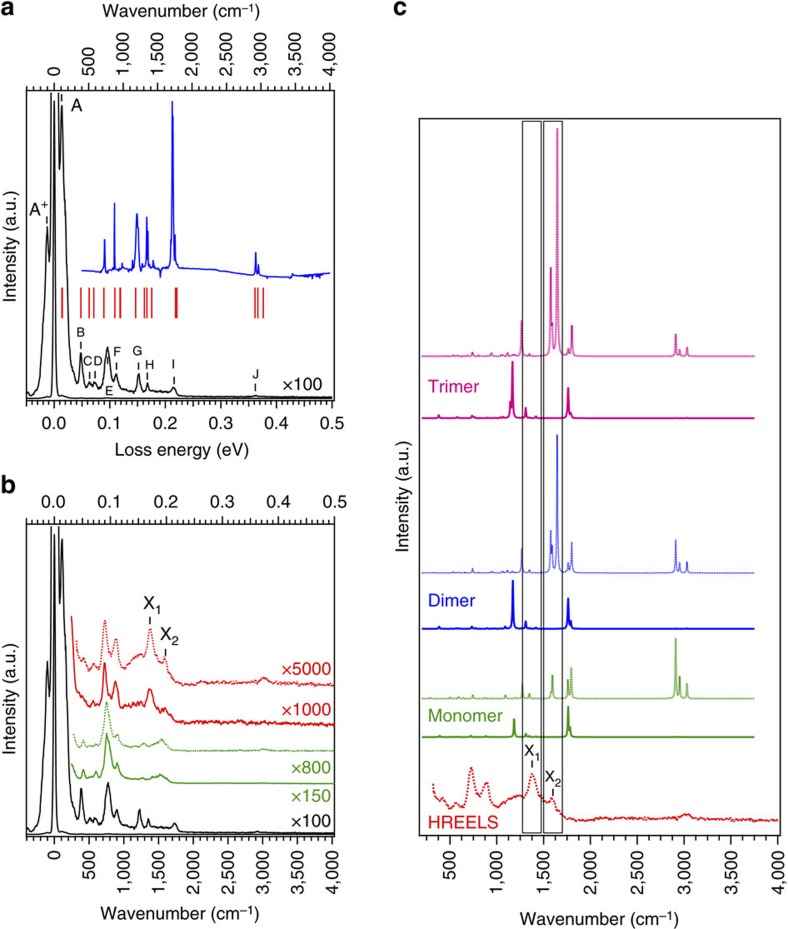

Optical methods such as infrared and Raman spectroscopies are powerful techniques of probing the vibrational modes of atoms and molecules in bulk material. However, when employed to the study of adsorbates on surfaces, the signals are usually very weak and difficult to extract from the background. And this becomes even more difficult when the substrate is a metal because of its high reflectivity in the infrared range. Due to the use of suitably chosen low-energy electrons, HREELS is extremely surface-sensitive. Despite the fact that its resolution is substantially less than in optical spectroscopies, HREELS is an adequate and efficient tool to study the vibrational modes of adsorbed molecules on metals. Figure 3a exhibits the HREELS data recorded on the pristine INDO4, that is, the thick film of INDO4/Ag(110), and the infrared spectrum of the INDO4 powder, together with the positions of infrared active modes as calculated from DFT. The good overall agreement between the different experimental set of data and the theoretical one allowed us to assign the different loss structures observed, as reported in Table 1. Figure 3b displays HREELS data of the pristine INDO4 (thick film, black curve), which serves as a reference to assign the peaks, together with that of the monolayer regime (supramolecular phase, green curve). No essential difference is observed between the loss signature of the pristine INDO4 and that of the monolayer phase. Mainly, peaks G to I are no longer present, or at least of weaker intensity. To explain this issue one has first to notice that loss features G, H and I mostly correspond to in-plane vibrational modes, that is, parallel to the surface, and do not belong to a fully symmetric representation (cf. Table 1). Then we should consider that in specular geometry, and for highly ordered film, the dipole scattering is the dominant mechanism. In such conditions, the selection rules state that only vibrations that belong to the totally symmetric representations can be observed38. Therefore according to the dipole selection rules and due to the symmetry of the involved G, H and I features, they cannot be observed at monolayer completion and in specular geometry. The fact that there are no substantial modification of the vibrational structure upon adsorption at the monolayer regime further suggests that the interaction between the INDO4 molecules and the underlying Ag(110) substrate is weak, that is, van der Waals interactions. The C–H stretching mode for the monolayer regime is measured at an energy of 3,017 cm−1, in contrast to the thick film case where two components at 2,944 and 3,041 cm−1 can be observed, corresponding to the C–H sp3 and C–H sp2 stretching modes, respectively38 (Supplementary Fig. 6). This suggests that the molecules underwent a dehydrogenation reaction, at least partially, leading to the disappearance of all CH2 groups. Dehydrogenation is sometimes observed to occur on silver surfaces already at room temperature or upon mild annealing45,56. The C–H stretching mode is observed in off-specular geometry only, that is, when the dipolar scattering mechanism is not the dominating one, in agreement with the flat lying adsorption observed by STM.

Figure 3. Vibrational characterization.

(a) High-resolution electron energy loss (HREELS) spectrum of INDO4 thick film (black), together with infrared spectrum of the INDO4 powder (blue) and theoretical infrared active modes (red sticks). The corresponding vibrational modes are assigned in Table 1. (b) HREELS spectra of the INDO4: thick film (black), monolayer (supramolecular phase, green), monolayer annealed at 380 °C (polymeric phase, red). Full line curves were recorded in specular geometry while dashed lines were taken in off-specular geometry. All spectra were normalized to the intensity of peak E at 775 cm−1. (c) Theoretical spectra of the infrared (full line) and Raman (dotted line) active vibrational modes for the monomer, the dimer and the trimer together with the HREELS spectrum obtained after annealing at 380 °C. Theoretical data have been scaled to the infrared spectrum of the pristine INDO4. For the sake of comparison the calculated infrared active modes of the monomer, dimer and trimer have been normalized to the peak at 1,760 cm−1. A similar normalization was done for the Raman active modes using the peak at 1,790 cm−1.

Table 1. Vibrational modes assigned to HREEL spectra.

| Label | HREELS | Infrared | Theory IR act. (sym.) | Theory R act. (sym.) | Assignment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TF | A+ | −107 | — | — | — | CCCH2 OPB* |

| A | 107 | — | 112 (B1U) | — | CCCH2 OPB | |

| B | 387 | — | 387 (B3U) | — | CCCO IPB | |

| C | 513 | — | 507 (B1U) | 498 (AG) | CH OPB | |

| D | 593 | — | 575 (B3U) | 565 (B3G), 589 (AG) | macro. OPB | |

| E | 775 | 732 | 721 (B3U) | 742 (AG) | macro. br., CC str. | |

| F | 903 | 875 | 880 (B1U) | — | CH OPB | |

| G | 1225 | 1201 | 1182 (B3U) | 1197 (B1G) | macro. br., CH sp2 IPB, wag. CH sp3 | |

| H | 1350 | 1344, 1361 | 1346 (B3U) | 1346 (AG) | sci. CH sp3 | |

| I | 1740 | 1713, 1723 | 1760 (B2U), 1781 (B3U) | 1758 (B1G), 1793 (AG) | CO str. | |

| J | 2944, 3041 | 2925, 2963 | — | 2911 (AG), 2952 (B2G), 3030 (AG) | CH str. sp3, CH str. sp2 | |

| Annealed ML | X1 | 1383 | — | 1307 (AU) | — | macro. br. |

| — | 1416 (AU) | — | macro. br., CH sp2 IPB | |||

| X2 | 1600 | — | — | 1574 (AG) | macro. br., C*=C* str. | |

| — | — | 1644 (AG) | C*=C* str. |

br., breathing mode; IPB, In-Plane Bending; IR act., Infrared active mode; macro., macrocycle; ML, monolayer; OPB, Out of Plane Bending; R act., Raman active mode; sci., scissor mode; str., stretching mode; TF, thick film; wag., wagging mode.

Values are given in cm−1.

+Indicates a gain process, the counter part of the loss one.

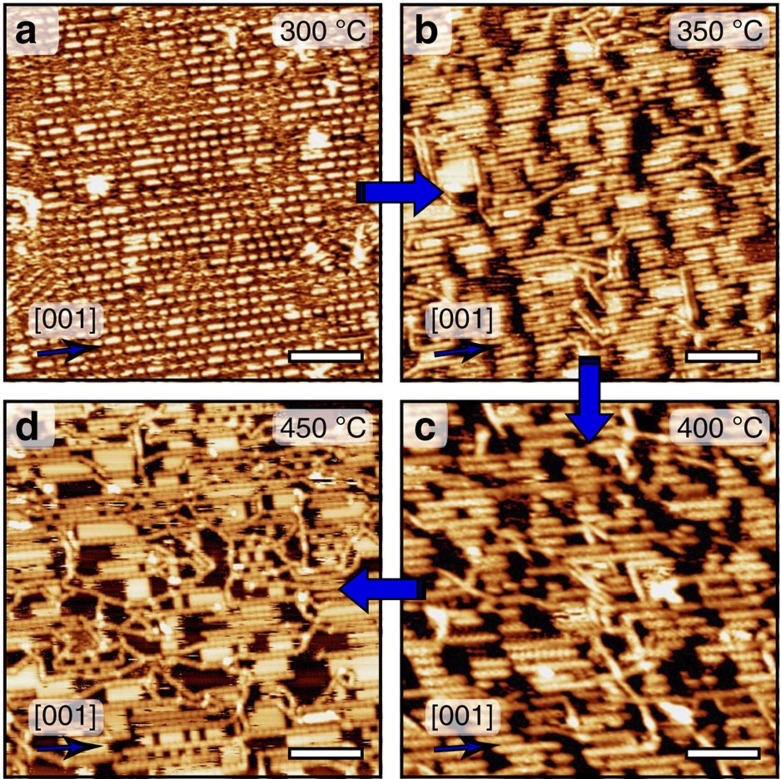

Polymeric phase

Covalent coupling is sequentially activated at more elevated temperatures (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. 7). Covalent dimerization (homo-coupling reaction) takes place through release of hydrogen and creation of a new C*=C* double bond (for example, dimer 2, Fig. 1). Molecular dihydrogen byproduct is expected to spontaneously desorb from noble-metal substrates under the conditions employed57. We assume here that the possibility of a C–C single bond formation is not allowed because the oligomeric structures are imaged perfectly homogeneous and parallel to the surface plane (Supplementary Fig. 8). This hypothesis is also supported by previous works devoted to the dimerization of 1,3-indandione derivatives where the dimer 2,2′-biindanylidene-1,3,1′,3′-tetraone could be formed by homo-coupling of 2,2-dichloro-1,3-indandione in the presence of copper58. Similarly, the reported conversion of 3,3′-dihydroxy-2,2′-bi-1H-indene]-1,1′dione to 2,2′-biindanylidene-1,3,1′,3′-tetraone by oxidation with 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ)59 is sustaining the possibility of an oxidation assisted by the metal surface providing the dimer 2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Nanoribbon formation and their evolution upon further annealing.

Scanning tunnelling microscopy images of the on-surface synthesis of aligned functional nanoribbons by the subsequent surface annealing or the direct deposition of INDO4 on Ag(110) substrate held at (a) 300 °C (b) 350 °C (c) 400 °C and (d) 450 °C. Scale bars, 8 nm.

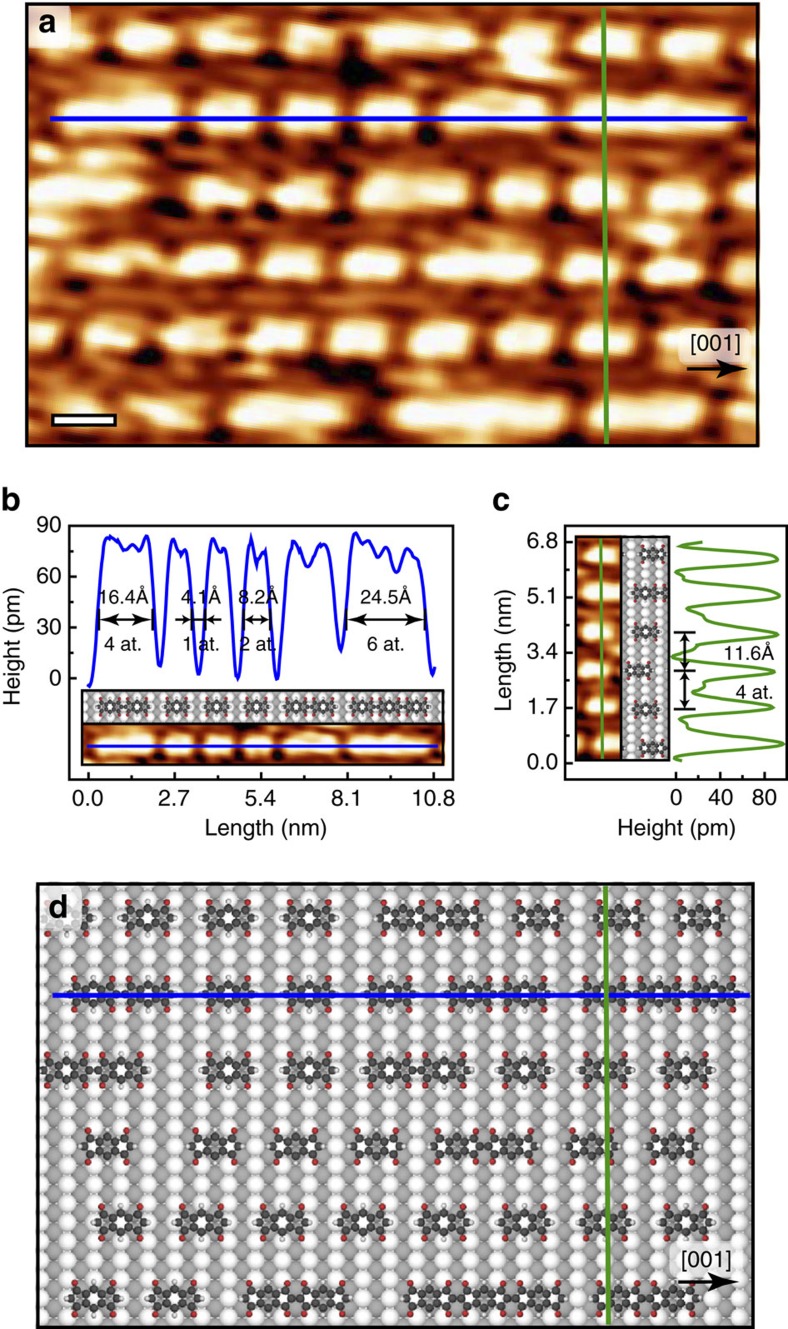

Annealing of the supramolecular phase, or deposition of INDO4 on a substrate held at 300 °C results in the formation of parallel molecular rows running along the [001] direction (Figs 4a and 5a). Within each row, elongated features of different sizes can be distinguished. Their lengths are restricted to 8.2, 16.4, 24.5 Å, consistent with the sizes of single isolated molecules, head-to-head covalently bonded dimers and trimers, respectively. Also, the distance of 4.1 Å between individual units along [001]-oriented rows (Fig. 5b) corresponds nicely to a single atomic periodicity of the underlying Ag surface, thus entailing molecular chain growth in perfect registry with the substrate. It is expected that INDO4 and its polymerized forms preferentially adopt type A adsorption site, which corresponds to the most stable configuration found in the room temperature supramolecular phase of Fig. 2, or eventually a shifted site by sliding by half a unit cell in the [001] direction. Remarkably, in all cases O atoms are similarly lying close to on-top sites of the Ag substrate (Fig. 5d). Besides, the strictly uniform inter-row spacing of 11.6 Å in the [1 0] direction corresponds to four-atomic distance of the Ag(110) substrate (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Fig. 9a,b).

0] direction corresponds to four-atomic distance of the Ag(110) substrate (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Fig. 9a,b).

Figure 5. First polymerization steps.

Deposition of INDO4 on a substrate kept at 300 °C lead to the formation of parallel rows composed of single isolated molecules, head-to-head covalently bonded dimers and trimers that are all oriented along [001] direction. (a) High-resolution scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) image. Scale bar, 1 nm. (b) Line profiles along a single molecular row in the [001] direction and (c) across parallel rows in the transverse [1 0] direction, indicated by blue and green lines in (a), respectively. 1 at. corresponds to 1 Ag lattice parameter. Epitaxy is preserved in both directions. (d) Tentative model of the molecular network presented in the STM image of (a).

0] direction, indicated by blue and green lines in (a), respectively. 1 at. corresponds to 1 Ag lattice parameter. Epitaxy is preserved in both directions. (d) Tentative model of the molecular network presented in the STM image of (a).

At the temperature of 300 °C the polymerization process is restricted to its first steps, providing exclusively dimers or trimers. Higher activation energy is required to extend the reaction to longer oligomers. In fact, the coupling mechanism for a dimer or a trimer may be significantly different than for an isolated molecule because fine epitaxial effects can take place due to the exceptionally strong catalytic implication of the metal substrate19,45,60. Also, the diffusivity of dimers and trimers is probably reduced, lowering similarly the reaction probability.

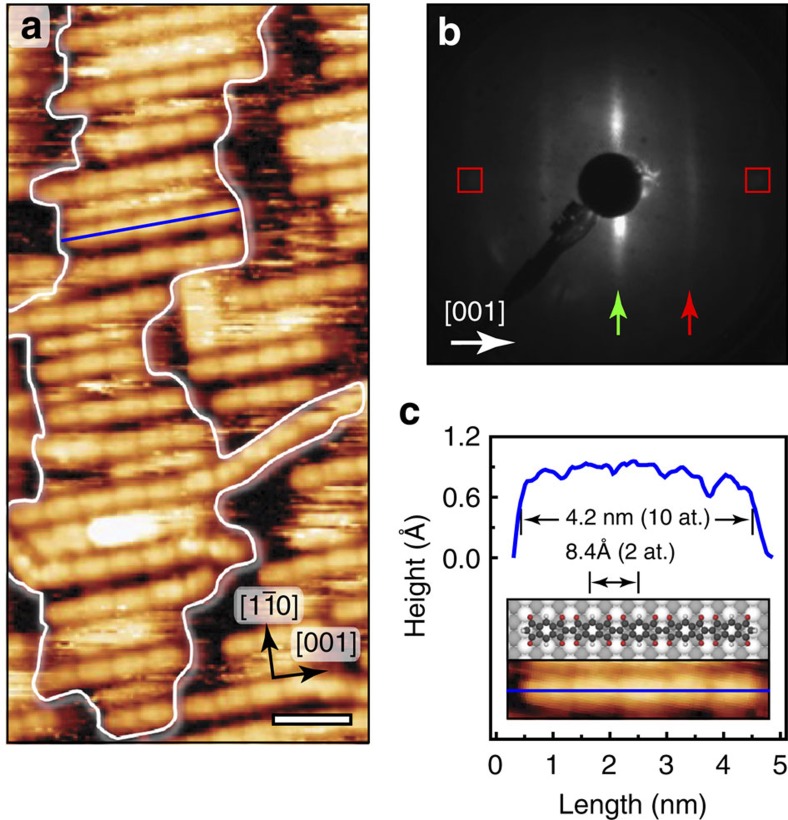

Annealing of the surface to 350 °C produces further modification of the assembly, namely the growth of longer straight covalent chains, with lengths corresponding principally from dimers to hexamers, still running along the [001] direction (Figs 4b and 6a). The monomeric units are distinguishable inside the covalently bonded chains with a periodicity of 8.2 Å (Fig. 6a,c). The ends of the parallel chains interact with each other and tend to accommodate in the perpendicular direction, leading to the formation of domains drastically elongated along the [1 0] direction, as highlighted by a white line in Fig. 6a. The chain interspacing is here non-uniform but corresponds mainly to integer numbers of substrate Ag atomic rows, providing thus a non-perfectly ordered structure in the [1

0] direction, as highlighted by a white line in Fig. 6a. The chain interspacing is here non-uniform but corresponds mainly to integer numbers of substrate Ag atomic rows, providing thus a non-perfectly ordered structure in the [1 0] direction. The corresponding LEED pattern confirms this poor order in the form of elongated spots along the [1

0] direction. The corresponding LEED pattern confirms this poor order in the form of elongated spots along the [1 0] direction, in agreement with the Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the STM images (Supplementary Fig. 9c,d). The periodic sequence generated inside the polymeric chains is represented as dim stripes along the [001] direction in the LEED pattern (Fig. 6b). The reciprocal distance corresponds to ∼8.2 Å (2 at.) or twice the substrate atomic periodicity in this direction, confirming the epitaxial growth of the polymeric chains. Occasionally, few covalent chains, referred to as transverse, are seen by STM in-between the patches, sometimes not strictly straight and occasionally aligned with [1

0] direction, in agreement with the Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the STM images (Supplementary Fig. 9c,d). The periodic sequence generated inside the polymeric chains is represented as dim stripes along the [001] direction in the LEED pattern (Fig. 6b). The reciprocal distance corresponds to ∼8.2 Å (2 at.) or twice the substrate atomic periodicity in this direction, confirming the epitaxial growth of the polymeric chains. Occasionally, few covalent chains, referred to as transverse, are seen by STM in-between the patches, sometimes not strictly straight and occasionally aligned with [1 0] direction. Also, a few unreacted molecules are still present on the surface.

0] direction. Also, a few unreacted molecules are still present on the surface.

Figure 6. Growth of functional nanoribbons upon surface annealing to 350 °C.

(a) High-resolution scanning tunnelling microscopy image showing head-to-head covalently bonded INDO4 chains. Scale bar, 2 nm. (b) Corresponding low-energy electron diffraction pattern (recorded at 23.3 eV) with Ag spots marked by the square outlines. The presence of vertical stripes, extended along [1 0], indicates non-uniform inter-chain spacing along the [1

0], indicates non-uniform inter-chain spacing along the [1 0] direction (green arrow) and molecular periodicity within polymeric chains oriented along [001] direction (red arrow). (c) Line profile along a pentameric molecular chain oriented in the [001] direction, indicated by blue line.

0] direction (green arrow) and molecular periodicity within polymeric chains oriented along [001] direction (red arrow). (c) Line profile along a pentameric molecular chain oriented in the [001] direction, indicated by blue line.

The reason for the limited size of the chains along [001] may arise from epitaxial stress. DFT calculations of free-standing oligomers (up to the pentamer) suggest a good epitaxy with the substrate: the length increase of the oligomer by adding one monomeric unit is 8.3±0.1 Å according to DFT while the size of 2 unit cells of Ag substrate along [001] is 8.2 Å. The small discrepancy (0.1 Å per monomer) is probably responsible for the existence of a chain size limit (hexamer to octamer, 5 to 7 nm) above which epitaxy is prohibited. Longer chain can grow only by deviating from perfect [001] epitaxial alignment. This further suggests that the reaction mechanism is intimately related to the adsorption configuration of the reactants, as it was shown for other on-surface syntheses19,60.

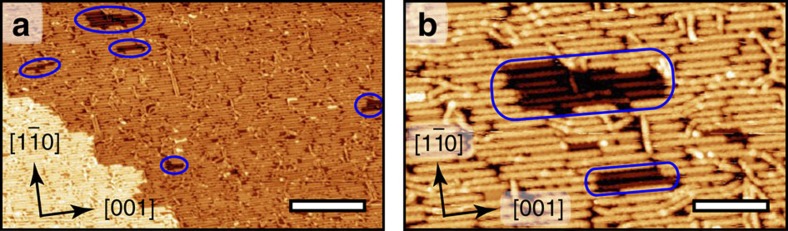

Remarkably here the coverage of the surface can be increased to monolayer range, thus providing a complete sheet of well-aligned organic nanoribbons (Fig. 7). Although it is suggested that at room temperature the molecules are weakly interacting with the substrate, the situation is very different at annealing temperature along the reaction pathway. Indeed, for high coverage and after annealing at 350 °C small pits of a few nm wide are sparsely observed inside the Ag substrate (Fig. 7b). The extraction of Ag adatoms from the surface is thus probably required in the reaction mechanism. Vacancy pits on Ag(110) are expected to annihilate readily at elevated temperature61. The molecular layer is thus also stabilizing, at least partially, their formation upon cooling back to room temperature. Indeed, small molecular structures are usually found inside the pits. Several STM images were sequentially recorded at room temperature to confirm the stability of covalent chains and vacancy pits, and the presence of isolated molecules (Supplementary Fig. 10; Supplementary Movie 1). The images taken on the same location demonstrate the presence of very mobile isolated molecules located in between the chains and in the pits of the surface. These molecules appear as structureless bright features, with slightly higher apparent height. On the other hand, the polymeric chains are perfectly stable (not diffusing) in this assembly within the measurement timeframe (≥1 h).

Figure 7. Full monolayer of aligned nanoribbons formed by INDO4 deposition on Ag(110) surface kept at 350 °C.

(a) Large scale and (b) high-resolution scanning tunnelling microscopy images. Pit formation is highlighted by blue oval contours. Scale bar, (a) 30 nm; (b) 10 nm.

At 400 °C annealing temperature, the molecular structure (Fig. 4c) is similar to that at 350 °C with no substantial elongation of the [001]-aligned polymeric chains. HREELS data for the polymer phase annealed at 380 °C are shown in Fig. 3b (red curves). Two clear peaks, labelled X1 and X2 appeared. As reported in Table 1, peak X1 can be assigned to an infrared active macrocycle-breathing mode and/or an in-plane bending mode of the sp2 C–H bonds (Supplementary Movies 2,3). According to DFT calculations, both modes are already observable for the monomer case but their intensity increases with the chain length (for dimers and trimers, see Fig. 3c). Therefore, since the HREELS signature of these features is much more intense upon annealing, one could emphasize, in relation with the STM data, that the homo-coupling reaction effectively occurs upon annealing. But more stimulating is the peak X2. According to its frequency this peak can only be assigned to two different, fully symmetric Raman active modes corresponding to a macrocycle-breathing mode and, most interestingly, to a C*=C* stretching mode (Table 1; Supplementary Movies 4,5). According to DFT calculations, the former mode is already observable for the monomer but its intensity is significantly increased for dimers and trimers (Fig. 3c). Also, the latter mode only appears upon annealing and oligomerization. In fact, peak X2 has a width larger than the elastic peak and can thus include in principle these two close but hardly distinguishable contributions (Supplementary Fig. 11). The presence of the peak X1 and the broader peak X2 thus clearly highlights the fact that annealing induces an on-surface reaction towards an effective homo-coupling of the INDO4 molecules. The signature of the C–H stretching mode (peak J) did not evolve upon annealing (Supplementary Fig. 6). A single component corresponding to C–H sp2 stretching mode is measured in off-specular geometry only. It is thus suggested that the dehydrogenation reaction, that occurred already in the supramolecular phase and that led to the disappearance of all CH2 groups, represents a first intermediate state towards the polymerization reaction.

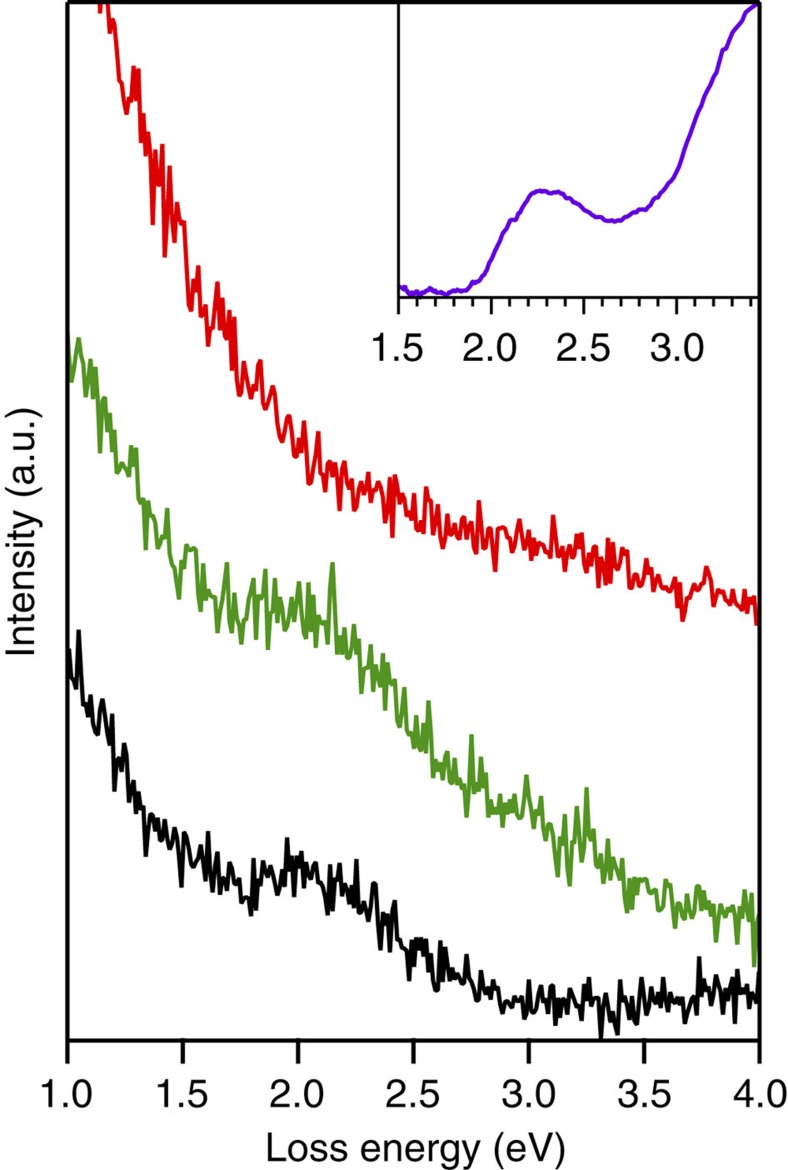

To further reinforce the conclusions drawn from the STM data and the analysis of the vibrational modes of the system, we studied the evolution of the electronic signature of the system with HREELS by analysing high-energy losses, that is, above 1 eV. For organic conjugated materials, this region corresponds to the excitation of the lowest energetic electronic transitions, mainly between the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) of the molecules and the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO). Figure 8 displays HREELS spectra of the thick film (black), monolayer (green) and monolayer annealed at 380 °C (red), together with ultraviolet–visible data from the pristine molecules. In the case of the thick film there is a large loss structure at about 2.1 eV (∼0.5 eV wide). This structure matches the one observed by ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy and is attributed to the lowest electronic transition between the HOMO and the LUMO of the pristine INDO4. At monolayer coverage and prior annealing, this loss feature is still present demonstrating that the electronic structure of INDO4 is more or less unchanged upon adsorption, as expected considering the weak molecule-substrate interaction62,63. After annealing, the loss structure at 2.1 eV is no longer distinguishable. There might be two main reasons for such observation. First, upon annealing some molecules would have desorbed and the HREELS signal became too weak. Second, due to the polymerization there is a bathochromic effect and the feature of the peak is hidden in the HREELS background which is higher at lower loss energy. According to the in situ STM measurements performed after annealing but prior to HREELS, the INDO4 coverage was still high, estimated to be 0.8 Ml (Supplementary Fig. 12). Therefore we believe that the fade of the loss structure at 2.1 eV confirms the polymerization upon annealing. Indeed, the decrease of the HOMO-LUMO gap is characteristic of the oligomerization of π-conjugated 1D or 2D organic systems37,64,65,66. Accordingly, the lowest excitation energies mainly from HOMO to LUMO evaluated by means of the time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) method are 3.36, 1.98, 1.95, 1.93, and 1.92 eV for the monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer and pentamer, respectively (see Supplementary Table 1 for a comparison of different functionals). Although our approach does not take into account the influence of the substrate interaction and electronic screening effect67,68, and intermolecular interactions, such as π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding, the computational results clearly demonstrate that a drastic red-shift of the transition peak appears at the initial step of oligomerization, that is, the formation of dimers, and then the lowest excitation energy is gradually reduced as the length of molecular ribbon increases.

Figure 8. High-energy loss region.

High-resolution electron energy loss (HREELS) spectra from 1 to 4 eV of the INDO4: thick film (black), monolayer (green), monolayer annealed at 380 °C (red). Top-right inset ultraviolet–visible spectrum of pristine INDO4 molecule in acetone.

At 450 °C annealing temperature the formation of transverse chains is significantly increased (Fig. 4d). These covalently bonded transverse chains thus likely originate from a different and subsequent reaction pathway, whereby the epitaxial conditions are lost. In fact most transverse ribbons are seen as continuous extensions of the finite size [001]-aligned chains. The deviation from the [001] orientation allows for relaxing the epitaxial stress that limits the primary chain growth. At higher temperatures additional conformational configurations can be extensively explored, allowing for the activation of a supplemental reaction pathway for non-aligned monomers. Additional chain growth is possible because isolated and unreacted molecules are still available at high temperature, as mentioned above for the 350 °C experiment. Finally, at 500 °C, the structure does not show significant modification with respect to that obtained at 450 °C (Supplementary Fig. 13). The observation of preserved covalent nanoribbons after such high annealing temperature attests for their remarkably high robustness.

In this work, we introduced a chemical functionality to perform surface-supported C–H bond activation and homo-coupling reaction. The combination of STM imaging and HREEL spectroscopy proved very efficient to effectively characterize the chemical transformations. The presence of reactive functional groups (carbonyl oxygen) preserved along the reaction path greatly enhanced the epitaxy of the precursors, which most probably facilitated the coupling mechanism. Extended theoretical support would now be required to elucidate the complex mechanism usually encountered in such surface-supported C–C coupling69. In particular, the role of the prior hydrogen-bonded self-assembly is probably essential to the formation of the first dimerization steps. In fact the original precursor presented here is highly versatile and can produce a large variety of supramolecular or covalent structures on other coinage metal surfaces, as we will show in future publications. Our results confirm that the characterization tools employed in the blooming field of on-surface synthesis and the advanced description of such well-defined systems are able to provide an exquisite understanding of the fine physicochemical processes taking place.

Methods

Sample preparation

The experiments were performed in two distinct ultra-high vacuum systems working at base pressures in the low 10−10 mbar range and equipped with LEED and standard facilities for sample preparation. The first experimental set-up was used for the STM measurements while the second set-up was dedicated to combined STM/HREELS studies.

The single-crystal Ag(110) surface was cleaned by several cycles of Ar+ bombardment followed by annealing. INDO4 molecules were provided by Sigma-Aldrich as rare and unique chemical. The precursors were thoroughly degassed prior to deposition onto the atomically clean substrate held at different temperature (room temperature to 400 °C). No difference could be observed for the structures formed by room temperature deposition and subsequent annealing or by deposition on a hot substrate. The molecular powder was thermally sublimated from an evaporator heated to 150 °C for typical dosing time of 30 min to allow tuning the formation of well-ordered supramolecular or covalently bonded organic films.

STM measurements

The self-assemblies of as-deposited INDO4 supramolecular architecture and the molecular film modified by thermal treatment were studied with a commercial Omicron VT-STM system operated at room temperature. The STM images were acquired in constant current mode with typical tunnelling current IT≈0.3 nA and sample bias VT≈1–1.5 V. All images were subsequently calibrated using atomically resolved images of the well-known Ag(110) surface. Images were partly treated with the free software WSXM70. The STM images allow to unambiguously identify organization and orientation of single molecules in H-bonded networks, and to resolve important aspects of internal structure within covalent chains.

HREELS measurements

HREELS measurements were carried out using a VSI DELTA 0.5 spectrometer. All spectra were recorded with the same incident electron beam energy of 5.8 eV, measured from the cutoff of the loss spectra, and with a typical energetic resolution of about 5 meV, estimated from the full width at half maximum of the elastic peak. Scattering geometry: θi=θs=64° for specular geometry, θi=64°, θs=58° for off-specular. For the high-loss measurements in off-specular geometry: θi=64°, θs=48°.

UV/Vis measurements

Ultraviolet–visible data were carried out in acetone and measured using a double-beam spectrophotometer SAFAS DES 190, in the range from 350 to 900 nm with a typical resolution of 4 nm.

Infrared measurements

Infrared measurements were recorded from 400 to 4,000 cm−1 using a Bruker IFS 66/S Fourier transform infrared spectrometer equipped with a HgCdTe detector. The data were recorded on INDO4 powder, in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode, using a Ge module and a typical resolution of 1 cm−1.

DFT calculations

DFT calculations at the gas phase were carried out to support experimental data, where the geometric and vibrational structures of monomer and all oligomers (from dimer to pentamer) were evaluated using M06-2X hybrid functional71 and 6-311++G(2d,p) basis set implemented in Gaussian 09 software package72. To compare the vibrational frequencies obtained from DFT calculations with experimental values, we scaled the computational data to the experimental infrared data using a compression factor of 0.929 and a rigid shift of 35 cm−1. In addition, the lowest excitation energy was also evaluated using the time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) method at the same level of theory. We used the ultrafine grid in numerical integration and the tight self-consistent field convergence criterion in all calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Kalashnyk, N. et al. On-surface synthesis of aligned functional nanoribbons monitored by scanning tunnelling microscopy and vibrational spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 8, 14735 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14735 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Table.

STM movie, 45 × 52 nm2, corresponding to a total real time of 52 min

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X1a

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X1b

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X2a

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X2b

Acknowledgments

Financial support from Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Aix-Marseille University is gratefully acknowledged. This work has been carried out thanks to the support of the A*MIDEX project (no ANR-11-IDEX-0001-02) funded by the ‘Investissements d′Avenir′ French Government program, managed by the French National Research Agency (ANR). J.J. acknowledges financial support from the National Research Foundation of Korea grant (2015R1C1A1A01052947). L. Giovanelli, F. Bocquet, M. Koudia, M. Abel from IM2NP, and C. Martin, S. Coussan from PIIM are acknowledged for motivating discussions and experimental support for optical measurements.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions S.C., N.K., F.D. and D.G. designed the experiments. N.K. and S.C. performed the STM experiments, E.S. and T.A. performed the HREELS experiments, J.O. and J.J. performed the theoretical analysis. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Dong L., Liu P. N. & Lin N. Surface-Activated coupling reactions confined on a surface. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2765–2774 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackinger M. On-surface polymerization - a versatile synthetic route to two-dimensional polymers. Polym. Int. 64, 1073–1078 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q., Gottfried J. M. & Zhu J. Surface-catalyzed C–C covalent coupling strategies toward the synthesis of low-dimensional carbon-based nanostructures. Accounts Chem. Res 48, 2484–2494 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk J. & Hanke F. Towards design rules for covalent nanostructures on metal surfaces. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 928–934 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. M., Zeng Q. D. & Wang C. On-surface single molecule synthesis chemistry: a promising bottom-up approach towards functional surfaces. Nanoscale 5, 8269–8287 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Garah M., MacLeod J. M. & Rosei F. Covalently bonded networks through surface-confined polymerization. Surf. Sci. 613, 6–14 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Franc G. & Gourdon A. Covalent networks through on-surface chemistry in ultra-high vacuum: state-of-the-art and recent developments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 14283–14292 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J., Lopez M. F. & Martin-Gago J. A. On-surface synthesis of cyclic organic molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4578–4590 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair S., Abel M. & Porte L. Growth of boronic acid based two-dimensional covalent networks on a metal surface under ultrahigh vacuum. Chem. Commun. 50, 9627–9635 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmolejo-Tejada J. M. & Velasco-Medina J. Review on graphene nanoribbon devices for logic applications. Microelectron. J. 48, 18–38 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yuan H., Li Y. & Chen Z. Two-dimensional iron-phthalocyanine (Fe-Pc) monolayer as a promising single-atom-catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction: a computational study. Nanoscale 7, 11633–11641 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. C., Choi J. W. & Grossman J. C. Two-dimensional covalent triazine framework as an ultrathin-film nanoporous membrane for desalination. Chem. Commun. 51, 14921–14924 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong D. Y. et al. Linear alkane polymerization on a gold surface. Science 334, 213–216 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L. L., Sun Q., Zhang C., Ding Y. Q. & Xu W. Dehydrogenative homocoupling of alkyl chains on Cu(110). Chem. Eur. J. 22, 1918–1921 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. M. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. et al. Synthesis of pyrene-fused pyrazaacenes on metal surfaces: toward one-dimensional conjugated nanostructures. ACS Nano 10, 1033–1041 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirera B. et al. Synthesis of extended graphdiyne wires by vicinal surface templating. Nano Lett. 14, 1891–1897 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill L. et al. Nano-architectures by covalent assembly of molecular building blocks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 687–691 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björk J. Reaction mechanisms for on-surface synthesis of covalent nanostructures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 083002 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Sun Q., Chen H., Tan Q. G. & Xu W. Formation of polyphenyl chains through hierarchical reactions: Ullmann coupling followed by cross-dehydrogenative coupling. Chem. Commun. 51, 495–498 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q. T. et al. Covalent, organometallic, and halogen-bonded nanomeshes from tetrabromo-terphenyl by surface-assisted synthesis on Cu(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 13018–13025 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. H., Shi X. Q., Wang S. Y., Van Hove M. A. & Lin N. A. Single-molecule resolution of an organometallic intermediate in a surface-supported Ullmann coupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13264–13267 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klappenberger F. et al. On-surface synthesis of carbon-based scaffolds and nanomaterials using terminal alkynes. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2140–2150 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faury T. et al. Side functionalization of diboronic acid precursors for covalent organic frameworks. CrystEngComm 15, 2067–2075 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sanchez C. et al. On-surface synthesis of BN-substituted heteroaromatic networks. ACS Nano 9, 9228–9235 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J. M. et al. Graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 896–900 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basagni A. et al. Tunable band alignment with unperturbed carrier mobility of on-surface synthesized organic semiconducting wires. Acs Nano 10, 2644–2651 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kezilebieke S., Amokrane A., Abel M. & Bucher J. P. Hierarchy of chemical bonding in the synthesis of Fe-phthalocyanine on metal surfaces: a local spectroscopy approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3175–3182 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veld M. I., Iavicoli P., Haq S., Amabilino D. B. & Raval R. Unique intermolecular reaction of simple porphyrins at a metal surface gives covalent nanostructures. Chem. Commun. 2008, 1536–1538 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirera B. et al. Thermal selectivity of intermolecular versus intramolecular reactions on surfaces. Nat. Commun. 7, 11002 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oteyza D. G. et al. Direct Imaging of Covalent Bond Structure in Single-Molecule Chemical Reactions. Science 340, 1434–1437 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. M. et al. On-Surface Synthesis of Rylene-Type Graphene Nanoribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4022–4025 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klappenberger F. Two-dimensional functional molecular nanoarchitectures – Complementary investigations with scanning tunneling microscopy and X-ray spectroscopy. Prog. Surf. Sci. 89, 1–55 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas L. et al. Synthesis and electronic structure of a two dimensional pi-conjugated polythiophene. Chem. Sci. 4, 3263–3268 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Matena M. et al. Aggregation and Contingent Metal/Surface Reactivity of 1,3,8,10-Tetraazaperopyrene (TAPP) on Cu(111). Chem. Eur. J. 16, 2079–2091 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Q. et al. Homo-coupling of terminal alkynes on a noble metal surface. Nat. Commun. 3, 1286 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiengarten A. et al. Surface-assisted dehydrogenative homocoupling of porphine molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9346–9354 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibach H. & Mills D. L. Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy and Surface Vibrations Academic Press (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Swami N., He H. & Koel B. E. Polymerization and decomposition of C-60 on Pt(111) surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 59, 8283–8291 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Houplin J. et al. Selective terminal function modification of SAMs driven by low-energy electrons (0-15 eV). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 7220–7227 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiaud L. et al. Low-energy electron induced resonant loss of aromaticity: consequences on cross-linking in terphenylthiol SAMs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 1050–1059 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B. et al. Synthesis of surface covalent organic frameworks via dimerization and cyclotrimerization of acetyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4904–4907 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers J. et al. Convergent fabrication of a nanoporous two-dimensional carbon network from an aldol condensation on metal surfaces. 2D Mater. 1, 034005 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Arado O. D. et al. On-surface reductive coupling of aldehydes on Au(111). Chem. Commun. 51, 4887–4890 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. Surface-controlled mono/diselective ortho C-H bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2809–2814 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krief P. et al. s-indacene-1,3,5,7(2H,6H)-tetraone (‘Janus dione') and 1,3-dioxo-5,6-indane-dicarboxylic acid: Old and new 1,3-indandione derivatives. Synthesis 2004, 2509–2512 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Goubard F. & Dumur F. Truxene: a promising scaffold for future materials. RSC Adv. 5, 3521–3551 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinet L. et al. Synthesis and characterization of new truxenones for Nonlinear optical applications. Chem. Mater. 18, 4259–4269 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sprick R. S., Thomas A. & Scherf U. Acid catalyzed synthesis of carbonyl-functionalized microporous ladder polymers with high surface area. Polym. Chem. 1, 283–285 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Sigalov M., Krief P., Shapiro L. & Khodorkovsky V. Inter- and intramolecular C-H...O bonding in the anions of 1,3-indandione derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 673–683 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Chetkina L. A. & Belsky V. K. X-Ray structure investigation of 1,3-indandione and 1,3-dicyanomethyleneindan derivatives: A review. Crystallogr. Rep. 53, 579–607 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Clair S. et al. STM study of terephthalic acid self-assembly on Au(111): hydrogen-bonded sheets on an inhomogeneous substrate. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 14585–14590 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bohringer M., Schneider W. D., Glockler K., Umbach E. & Berndt R. Adsorption site determination of PTCDA on Ag(110) by manipulation of adatoms. Surf. Sci. 419, L95–L99 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T. The hydrogen bond in the solid state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 48–76 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju G. R. Hydrogen bridges in crystal engineering : Interactions without borders. Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 565–573 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli L. et al. Combined photoemission spectroscopy and scanning tunneling microscopy study of the sequential dehydrogenation of hexahydroxytriphenylene on Ag(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 14899–14904 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-L., White J. M. & Koel B. E. Chemisorption of atomic hydrogen on clean and Cl-covered Ag(111). Surf. Sci. 218, 201–210 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg A. & Moubasher R. 50. Studies on indene derivatives. Part IV. Synthesis of bis-1 : 3-diketoindanylidene, and experiments with ‘ninhydrin' (triketoindane hydrate). J. Chem. Soc. 212–214 (1949). [Google Scholar]

- Khodorkovsky V., Ellern A. & Neilands O. A new strong electron acceptor. The resurrection of 2,2′-biindanylidene-1,3,1′,3′-tetraone (BIT). Tetrahedr. Lett. 35, 2955–2958 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Bieri M. et al. Two-dimensional polymer formation on surfaces: insight into the roles of precursor mobility and reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 16669–16676 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern K., Laegsgaard E. & Besenbacher F. Brownian motion of 2D vacancy islands by adatom terrace diffusion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5739–5742 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch N., Vollmer A., Duhm S., Sakamoto Y. & Suzuki T. The effect of fluorination on pentacene/gold interface energetics and charge reorganization energy. Adv. Mater. 19, 112–116 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Auerhammer J. M., Knupfer M., Peisert H. & Fink J. The copper phthalocyanine/Au(100) interface studied using high resolution electron energy-loss spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. 506, 333–338 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Luo D., Cheng L., Zhao K. & Ma H. B. Electronic structure properties of two-dimensional pi-conjugated polymers. Macromolecules 49, 1305–1312 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Gutzler R. & Perepichka D. F. pi-Electron conjugation in two dimensions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16585–16594 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasseur G. et al. Quasi one-dimensional band dispersion and surface metallization in long-range ordered polymeric wires. Nat. Commun. 7, 10235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt A. & Schuurmann G. COSMO: a new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Transac. 2, 799–805 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Neaton J. B., Hybertsen M. S. & Louie S. G. Renormalization of molecular electronic levels at metal-molecule interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 216405 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floris A. et al. Driving forces for covalent assembly of porphyrins by selective C-H bond activation and intermolecular coupling on a copper surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5837–5847 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horcas I. et al. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Inst. 78, 013705 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. & Truhlar D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J. et al. Gaussian 09 Gaussian, Inc. (2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Table.

STM movie, 45 × 52 nm2, corresponding to a total real time of 52 min

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X1a

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X1b

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X2a

Vibrational mode assigned to peak X2b

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.