Abstract

Background

The pathogenicity of copy number variations (CNV) in neurodevelopmental disorders is well supported by research literature. However, few studies have evaluated the utility and counseling challenges of CNV analysis in the clinic.

Methods

We analyzed the findings of CNV studies from a cohort referred for clinical genetics evaluation of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), developmental disability (DD), and intellectual disability (ID).

Results

Twenty-two CNV in 21 out of 115 probands are considered to be pathogenic (18.3%). Five CNV are likely pathogenic and 22 CNV are variants of unknown significance (VUS). We have found 7 cases with more than 2 CNV and 2 with a complex rearrangement of the 22q13.3 Phelan-McDermid syndrome region. We identified a new and de novo 1q21.3 deletion that encompasses SETDB1, a gene encoding methylates histone H3 on lysine-9 (H3K9) methyltransferase, in a case with typical ASD and ID.

Conclusions

We provide evidence to support the value of CNV analysis in etiological evaluation of neurodevelopmental disorders. However, interpretation of the clinical significance and counseling families are still challenging because of the variable penetrance and pleotropic expressivity of CNVs. In addition, the identification of a 1q21.3 deletion encompassing SETDB1 provides further support for the role of chromatin modifiers in the etiology of ASD.

Introduction

The discovery of copy number variations (CNV) in patients with various neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (ASD), developmental disability (DD), and intellectual disability (ID), has supported the use of CNV analysis in clinical genetics practice[1, 2]. Endorsed by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) [3], CNV analysis using array-based comparative genomic hybridization (Array-CGH) or chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) is now routinely performed in clinical genetics laboratories. A consensus statement, published in 2010, recommended CMA as the first tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with DD and/or congenital anomalies [4]. Evidence accumulated in the research literature has strongly supported the pathogenic role of rare and de novo CNV in ASD, DD, and ID [5, 6]. Numerous large-scale research studies have identified CNV in various genomic loci in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders, primarily ASD [7, 8]. However, for the majority of CNV reported in the research literature, the calling for pathogenicity of a given CNV is determined by a statistical comparison of its frequency in cases and controls. Few studies have assessed the clinical utility and counseling challenges of genome wide CNV analysis in the clinic. In this study, we report the yield and specific findings of CNV analysis in 115 patients referred to the Duke Autism Genetics Clinic for clinical genetics evaluation of ASD and DD/ID. Most importantly, we report a novel deletion of chromosome 1q21.3 encompassing the H3K9 methyltransferase SETDB1 gene, and two cases (#37 and #38) of complex chromosomal rearrangements involving the Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) region, located at chromosome 22q13.3, which is associated with ASD and ID.

Results

Study subjects

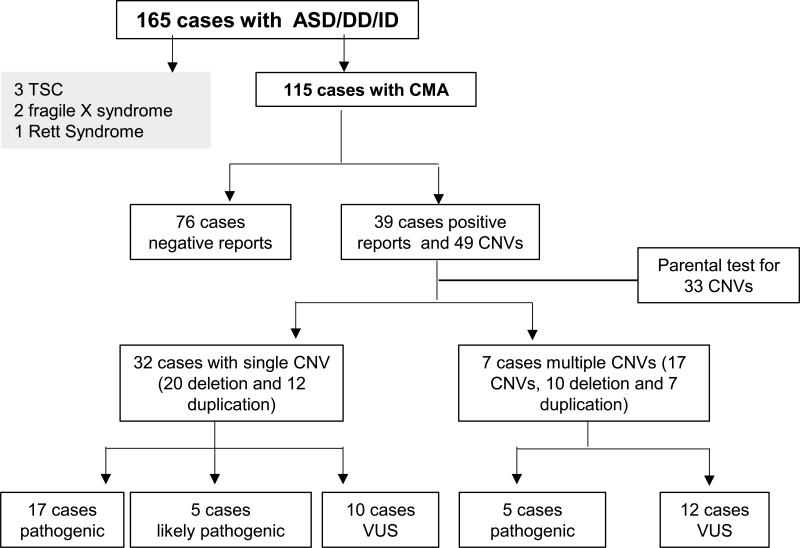

CMA was performed in 115 out 165 cases (69.7%) referred for genetics evaluation of ASD/DD/ID (Figure 1). The reasons varied for why CMA was not performed for 50 of the cases. The lack of insurance coverage and parental consent were two major issues encountered. CMA was performed in 83 males and 32 females with male to female ratio of 2.6 to 1. The mean age at the time of evaluation was 5.7 years, ranging from 18 months to 15.1 years with a 95% confidence interval of 5-6.3 years. There were 66 cases (66/115, 57.4 %) with a confirmed primary diagnosis of ASD and 49 cases (49/115, 42.6%) with the primary diagnosis of DD or ID at the time referred for clinical genetics evaluation. The clinical evidence to support these diagnoses varied. DSM-IV, DSM-5, ADOS, and ADI-R were used to support the diagnosis of ASD. IQ and DQ scores were used for diagnosis of ID and DD respectively. The referral providers include general pediatrician (33%), developmental pediatrician (41%), neurology (24.8%), others including child psychiatry and clinical psychology (1.2%).

Figure 1.

The summary of genetic evaluation of 165 cases with ASD, ID, DD in genetic clinic

Basic genetic evaluation

Prior to referral to the Autism Genetics clinic, the primary care providers or other sub-specialty providers had performed a basic genetic evaluation for these cases. These included chromosome analysis, and basic biochemical screening for disorders related to inborn errors of metabolism. In the Autism Genetics Clinic, molecular testing for fragile X syndrome was recommended for all cases and completed in >93% of cases. Molecular testing for Rett syndrome and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) was requested if the clinical presentations suggested these diagnoses. We have confirmed 2 cases of fragile X syndrome (2/165, 1.2%), 3 cases of TSC (3/165, 1.8%), and 1 case (1/165, 0.6%) of Rett syndrome (Figure 2) (Table 1).

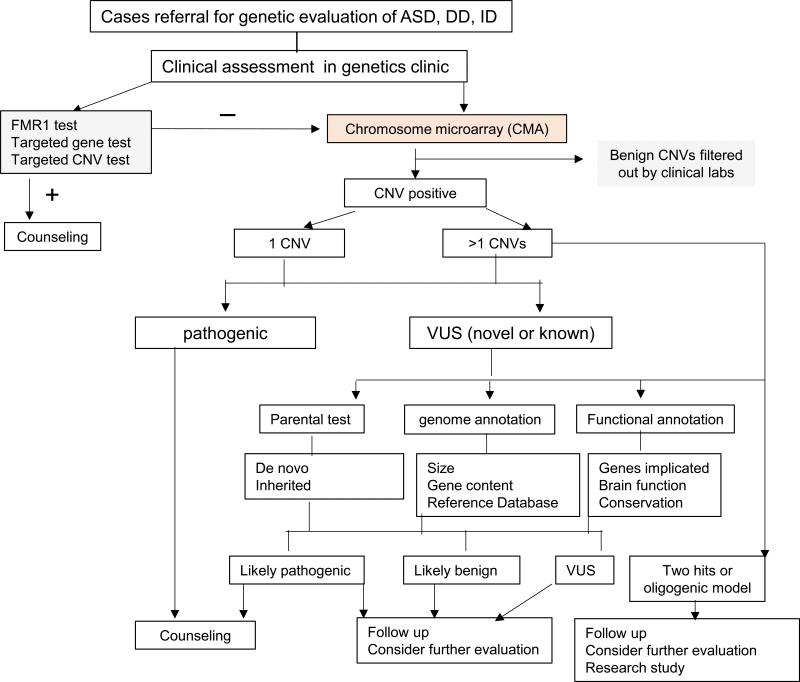

Figure 2.

A patient (case #18) with a 260-kb deletion at 1q21.3 that disrupts the SETDB1 gene. A) A facial profile of patient. Noted for slightly deep set of eyes, mild hypotelorism, small chin and short neck. B) A local view of the 17p13.3 deletion from SNP array. C) The diagram of deletions of SETDB1 and other genes in 260 kb deleted interval. D) FISH confirmation for the deletion in proband but absence in both parents.

Table 1.

CNVs identified from individuals referred for clinical genetics evaluation in autism clinic

| A. Single CNV | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Chromosome Location |

Deletion/ Duplication |

Position | Size, kb |

Assembly | Parent of Origin |

Primary Diagnosis |

Novel CNV |

Clinical Significance |

FMR1 | MeCP2 | Karotype |

| Pathogenic | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1p36.31 | deletion | 4,901,696-10,067,420 | 5,165 | hg18 | mother normala | DD | - | ||||

| 2 | 1p36.32 | deletion | 4,075,966-11,812,055 | 7,700 | hg18 | De novo | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 3 | 2q32.1 | deletion | 186,401,261-186,791,896 | 391 | hg18 | NA | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 4 | 3q29 | deletion | 193,800,001- 199,501,827 | 5,701 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | NA | NA | - | |

| 5 | 14q12 | deletion | 25,488,077-28,883,347 | 3,400 | hg18 | NA | ID | - | - | - | NA | |

| 6 | 15q11.2-q13.1 | deletion | 20,085,783-26,714,565 | 6,600 | hg18 | maternal | Angelman Syndrome | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 7 | 15q13.2-q13.3 | deletion | RP11-38E12->RP11-164K24 | 900 | hg17 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 8 | 15q13.3 | deletion | 30,073,735-32,446,830 | 2,370 | hg19 | maternal | ASD | - | ||||

| 9 | 15q26.1 | duplication | 90,486,082-90,967,701 | 482 | hg18 | maternal | ASD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 10 | 16p11.2 | deletion | 29,425,200-30,085,308 | 660 | hg19 | De novo | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 11 | 16p13.11 | deletion | RP11-489O1 | 200 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | NA | NA | NA | |

| 12 | 16p13.11 | deletion | 14,899,719-16,508,304 | 1,600 | hg19 | maternal | ASD | - | - | - | - | |

| 13 | 16p13.12 | deletion | 12,664,828-12,877,151 | 212 | hg17 | NA | CHARGE Syndrome | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 14 | 18q22.1 | deletion | 62,098,937-62,364,101 | 265 | hg18 | mother normala | ASD | - | - | - | - | |

| 15 | 22q11.21 | deletion | 17,173,935-19,941,337 | 2,700 | hg18 | De novo | ASD | - | - | - | - | |

| 16 | 22q11.21 | duplication | 17,173,935-20,164,236 | 3,000 | hg18 | mother normala | ASD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 17 | Xp11.4 | deletion | 38,310,495-38,402,885 | 92 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| likely Pathogenic | ||||||||||||

| 18 | 1q21.2 | deletion | NA | 260 | hg18 | De novo | ASD | + | - | NA | - | |

| 19 | 5q12.1-q12.3 | duplication | 61,718,070-64,507,614 | 2,800 | hg18 | paternal | ASD | + | - | - | - | |

| 20 | 7q31.1 | duplication | 109,999,318-110,819,951 | 821 | hg19 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 21 | 15q26.3 | duplication | 97,226,481-98,882,636 | 1,600 | hg18 | maternal | ASD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 22 | 16p12.1 | deletion | 21,883,228-22,338,859 | 456 | hg18 | paternal | ASD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| Variant of Unknown Significance (VUS) | ||||||||||||

| 23 | 4q22.2 | duplication | 94,645,324-95,366,771 | 721 | hg18 | mother normala | ASD | - | NA | NA | NA | |

| 24 | 6p21.1 | deletion | 44,968,645-45,091,828 | 123 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 25 | 6p21.2 | duplication | RP3-350J21->RP1-278E11 | 1,000 | hg17 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | - | |

| 26 | 8p22 | duplication | 13,400,616-14,700,476 | 1,299 | hg19 | NA | ASD | - | - | - | - | |

| 27 | 11q22.3 | deletion | 103,313,942-103,367,161 | 53 | hg19 | NA | ASD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 28 | 12q24.11 | duplication | 109,501,323-109,603,748 | 100 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | - | |||

| 29 | 13q12.11 | deletion | 19,695,316-20,002,412 | 307 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | NA | NA | NA | |

| 30 | 17p12b | duplication | 14,035,412-15,423,228 | 1,380 | hg18 | maternal | DD | - | - | NA | NA | |

| 31 | 18q12.2 | duplication | 32,161,410-32,635,174 | 474 | hg18 | NA | DD | + | - | NA | NA | |

| 32 | Xq21.31 | duplication | RP11-192B18 | 2,700 | hg17 | maternal | ASD | - | - | NA | - | |

| B. Multiple CNVs | ||||||||||||

| 33 | 5q35.3 15q11.2-q13.1 |

deletion duplication |

179,815,908-180,459,915 21,192,943-26,234,399 |

644 5,041 | hg17 | De novo paternal | ASD | - | Unclear Pathogenicc | - | - | - |

| 34 | 1q21.1 1q21.1 |

duplication deletion |

144,083,908-144,503,409 144,643,813-146,297,795 |

420 1,600 |

hg18 | paternal De novo | DD | + + |

Unclear Pathogenic | - | NA | NA |

| 35 | 9p21.3-p21.2 Yp11.2 |

deletion deletion |

24,863,950-26,314,013 6,460,193-7,035,072 |

1,400 575 |

hg18 | maternal paternal | DD | - - |

Unclear Unclear |

NA | NA | NA |

| 36 | 16q24.3 21q22.13 |

duplication deletion |

88,195,201-88,504,477 37,291,678-37,390,702 |

309 99 |

hg18 | paternal paternal |

ASD | - - |

Unclear Unclear |

- | NA | N/A |

| 37 | 1p31.1 16p13.2 22q13.33 |

deletion duplication deletion |

75,731,050-76,402,593 8,753,360-9,202,843 49,320,608-49,581,309 |

672 449 260 |

hg18 | maternal mother normal mother normal |

Phelan-McDermid syndrome | - | Unclear Pathogenic Pathogenic |

- | - | - |

| 38 | 22q13.31 22q13.31 22q13.32-q13.33 |

duplication deletion deletion |

44,744,569-45,629,066 45,629,066-46,956,456 49,059,493-51,197,838 |

884 1,330 2,100 |

hg19 | NA NA NA |

Phelan-McDermid syndrome | - - - |

Unclear Unclear Pathogenic |

- | NA | NA |

| 39 | 4q28.1-q28 12p13.33 Xq28 |

deletion duplication duplication |

126,784,753-127,148,514 733,738-880,267 153,444,055-154,533,675 |

363 156 1,089 |

hg18 | paternal maternal maternal |

ASD | - - - |

Unclear Unclear Unclear |

- | NA | NA |

Not present in mother but father was not available for study

The CNV gain is the known cause for the Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A. So this is likely an incidental finding.

The paternal duplication has been implicated in individuals with mild or moderate ASD and ID in literature. See discussion for the clinical relevance in this case in text.

Abbreviation: NA: not available; −: negative; +: positive

Copy number variations (CNV)

Copy number variant analysis was performed in clinical laboratories using three different array platforms. The BlueGnome CytoChip v2 comparative genomic hybridization array was used in 18 cases (15.7%), the Affymetrix v6.0 single-nucleotide polymorphism array was used in 69 cases (60%), and the Affymetrix Cytoscan HD array was used in 28 cases (24.3%). These analyses reported a total of 49 pathogenic or potentially clinically relevant CNV in 39 out of 115 patients (Figure 1). CNV considered to be not clinically relevant, or benign, were not reported by clinical laboratories. Thirty-two cases had a single CNV (20 deletions and 12 duplications), and 7 patients had more than one CNV (4 cases with 2 CNV and 3 cases with 3 CNV). Parental tests, including both father and mother, were performed for 33 of 49 CNV. Six CNV (6/33, 18.2%) were de novo, and 27 CNV (27/33, 82.8%) were inherited. Seven CNV (7/49, 14.3%) were detected in the mother but the father was not tested, and parents were not available to be tested for 9 CNV. The clinical relevance of the 49 CNV identified was assessed first by the clinical laboratories based on the size, inheritance, gene content, and previous clinical and research reports in published literature. We performed an additional assessment based on further literature review, genome and gene function annotation following the recommendations by others in literature [9,10]. In some cases, the further research studies in extended family members were conducted. We categorized the CNV as “pathogenic” if the same CNV had been previously implicated in a known deletion or duplication syndrome, or a similar disease phenotype with good evidence in literature. For CNV that are rare, novel, and likely disease causing, we defined them as “likely pathogenic” based on assessment of size of CNV, inheritance pattern, and functional annotation of the genes within the deleted or duplicated interval of CNV. CNV lacking sufficient evidence to support their pathogenicity were classified as “Variants of Unknown Significance” (VUS). We concluded that 22 CNV (17 single CNV and 5 CNV found in 4 probands with more than one CNV) are “pathogenic” because the same CNV has been associated with ASD, ID, and/or DD in previous reports in literature. Five CNV [5 single CNV (Table 1)] were “likely pathogenic” and 22 were “VUS”. Because there is evidence in literature supporting that the 15q11.2-q13.1 duplication, identified in #33, can cause mild ASD and ID [11,12], we classified it as pathogenic (see detail discussion below). However, the pathogenicity of this duplication is not certain in this family. Other genetic defects may also contribute to the clinical presentations of both siblings.

Cases with single CNV

Pathogenic CNV

The single CNV found in 17 probands were considered to be pathogenic (Table 1). These CNV included the maternal deletions of 1p36.3, 15q11-q13, and deletions of 16p11.2, 2q32.1, 3q29, and 22q11.3 that are frequently reported in the literature. For the CNV that are known to be pathogenic and have a known parental origin, 9 out 13 (69.2%) were inherited from reported healthy and normal parents. This is higher than that of inherited CNV reported in other research studies in literature [13,14] although this may also be biased because parental testing was not done in other cases.

Likely pathogenic CNV

Five cases have single CNV that are likely pathogenic including copy number loss in chromosomal regions 1q21.3 and 16p12.1 and copy number gain in 5q12.1-q12.3, 7q31.1, and 15q26.3. The 1q21.3 deletion is de novo but the others are inherited. These CNV have neither been reported to associate with ASD or ID consistently nor are present in a large number of controls. A de novo 210 Kb deletion of 1q21.3 was found in an 11 year old Caucasian male with ASD, seizures, developmental delay, and mild facial dysmorphisms including small chin and flat nasal bridge, and flat feet (case #18, Figure 2). This CNV has not been previously reported in the literature. There are 10 genes (ARNT, SETDB1, CERS2, ANXA9, FAM63A, PRUNE, CDC42SE1, BNIPL, MLLT11, C1orf56) mapped in the deleted interval. CERS2 encodes a ceramide synthase [15] and SETDB1 encodes a histone methyltransferase which methylates histone H3 on lysine-9 (H3K9)[16]. The function of the other genes is either unrelated to brain function or poorly characterized. For the other 3 CNV gains in this category, there are case reports describing individuals with variable clinical presentations including ID and DD[17-20]. However, the correlations or causal roles of these CNV with particular clinical phenotypes have not been firmly established. We also identified a maternally inherited duplication of 17p12, a known cause for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A), in the case (#30) of 9-year-old boy with dysmorphic face, hypospadias, short stature, DD, and ID but no sign of neuropathy at the time of evaluation. The ASD, DD, and ID have not been reported individuals with CMT1A in the literature. Although it is possible that this duplication may contribute to some clinical features in the proband, a more plausible interpretation is that this is simply an incidental finding.

Variant of Unknown Significance (VUS)

Ten of the CNV identified are novel and rare, and their clinical significance is currently unknown. None of these CNV have been reported in the literature or in reference database. The size of these CNV is generally <2Mb and the inheritance is either de novo or inherited from healthy parents. The functions of genes within these CNV are either unknown or not revealing based on the review of literature. Therefore, it is not possible to assign a causal role to these CNV at this point.

Cases with multiple CNV or a complex genomic rearrangement

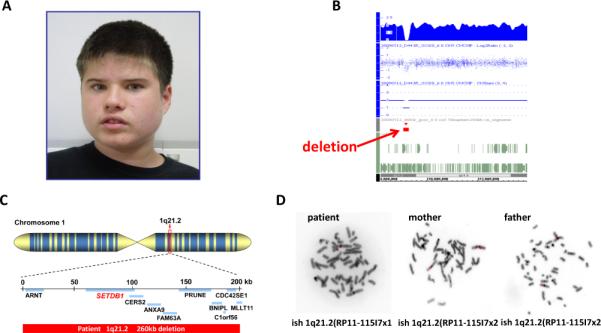

Seven cases had CNV in more than one chromosomal region. Four cases had 2 CNV and 3 cases had 3 CNV (Table 1). Two cases with 3 CNV (#37 and #38) had copy number loss of the Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) region located at 22q13.3. In addition to this CNV in the PMS region, case #37, has a copy number loss at 1p31.1 and a copy number gain at 16p13.2. In the 22q13.3 PMS region of this patient, a 260 kb deletion began at linear position 49,320,608 and ended at 49,581,309 (www.genome.ucsc.edu; hg19). This interval overlaps 12 known genes including SHANK3, a causative gene for ASD and a key player in PMS[21,22]. The proband's clinical features include profound speech delay, motor development delay, severe intellectual disability, repetitive behaviors, significant self-injurious behavior and aggression. Interestingly, her social behavior and social communication appear much less affected compared to other individuals with PMS. In the 1p31.1 region, a 672 kb maternally inherited loss was identified that includes 11 known or predicted genes, 4 of which, ACADM, RABGGTB, MSH4, and ST6GALNAC3, are listed in OMIM. In the 16p13.2 region, a 449 kb copy number gain was found that includes 10 known or predicted genes, including ABAT, PMM2, and USP7 which are listed in OMIM. Chromosome analysis and FISH analysis showed no evidence of an unbalanced chromosomal translocation. The deletion at 1p31.1 was confirmed to be present in the mother, however, the duplication of 16p13.2 and the deletion of 22q13.3 were not. Unfortunately, the father was not available to determine the inheritance of the CNV in 22q13.3 and 16p13.2. Case #38 was a 13-year-old boy with severe ASD, non-verbal, seizures, and global developmental delay. CNV analysis revealed a complex rearrangement involving the 22q13.3 PMS region as diagramed in Figure 3. A proximal interstitial duplication of 884 kb in the 22q13.31 region (44,744,569 to 45,629,066) is adjacent to an interstitial deletion of at least 1.3 Mb in the 22q13.31 region (45,629,259 to 46,956,456), followed by a region of normal copy number and then a terminal deletion of at least 2.1 Mb of the 22q13 region (49,059,493 to 51,197,838) (hg19). The terminal deletion includes the SHANK3 gene. These rearrangements were de novo and similar rearrangements have not been reported in the literature.

Figure 3.

A diagram of complex chromosomal rearrangements in the 22q13 Phelan-McDermid region in case #38. The position for each CNV and genes disrupted in deleted or duplicated interval is diagramed. SHANK3, the key gene for Phelan-McDermid syndrome, is highlighted.

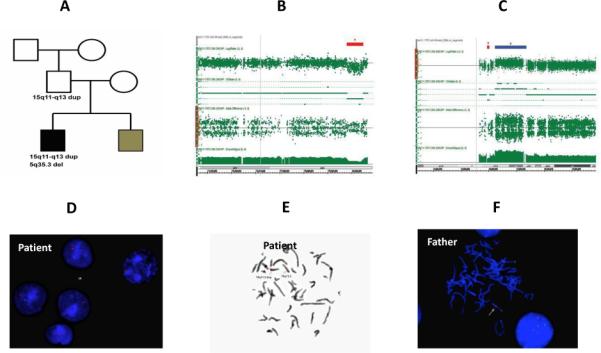

One of the cases with 2 CNV (#37) has a copy number gain in the 15q11-q13 Angelman syndrome (AS) and Prader-Willi syndrome region (PWS). The proband and his male sibling were affected by ASD (Figure 4). The older brother was more severely affected than the younger sibling. The older sibling carries a 5 Mb interstitial duplication of the 15q11.2-q13.1 AS and PWS region that was inherited from his healthy and normal father. The proband's younger affected bother and unaffected sister did not carry this duplication. This duplication was most likely a de novo event in the father because the paternal grandparents did not carry the same duplication in blood leukocyte DNA although the possibility of germline mosaicism could not be ruled out. The older sibling also carries a de novo 644 kb interstitial deletion of 5q35.3. Five OMIM genes including CNOT6, SCGB3A1, FLT4, MGAT1, and BTNL3 were mapped in the deleted interval of 5q35.3 region. MGAT1 is known to be involved in brain function by encoding a N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, an enzyme for the glycosylation of proteins [1]. However, screening for a glycosylation disorder by carbohydrate-deficient transferring analysis was unremarkable. Maternal duplication of 15q11-q13 is strongly associated with ASD while the pathogenic role of the same duplication of paternal origin in ASD and ID has not been firmly established [11-12,23-24]. The deletion of 5q35.3 has not been reported in literature to be associated with any disease phenotype.

Figure 4.

A patient (case #33) with CNV of 5q35.3 deletion and the 15q11-q13 duplication. A) A three generation pedigree. The proband has severe end of ASD and young brother has moderate end of ASD. The proband carries a de novo 640kb deletion at 5q35.3 region and paternally inherited 5Mb duplication of the 15q11-q13 region. Sibling brother, sister, mother, paternal grandmother and paternal grandfather do not carry either CNV. B) Local view of 5q35.3 deletion by CMA. C) Local view of 15q11-q13 duplication by CMA. D) Interphase FISH of the proband shows the duplication of 15q11-q13 probe. E) Metaphase FISH of the proband shows the duplication of 15q11-q13. F) Interphase FISH of father shows the same duplication of 15q11-q13.

Discussion

Clinical benefit of CNV analysis

Based on the results of CNV analysis, performed in clinical laboratories, and additional research analysis for some cases, we detected “pathogenic” CNV in 21 out 115 individuals (18.3%) with ASD and/or ID referred to our Autism Genetics Clinic (20 cases with single and 1 case with two CNV). Our detection rate of pathogenic CNV is slightly higher than that of 10-15% reported in other research studies [4, 13]. The difference is likely due to ascertainment bias of our patient cohort as it is possible that the patients referred to genetics clinic are more probably more severely affected. A significant number of cases in which CNV are considered to be pathogenic and parental origins are known in our cohort were inherited (9/13, 46.1%). The frequency of inherited CNV appears higher than expected. Unfortunately, the parental origins of CNV are not fully investigated in many research studies of genome wide CNV analysis for ASD in the literature [8, 25]. Most of the parents carrying the CNV identified in their affected children do not have significant medical or mental health problems based on review of available medical records although careful clinical and neuropsychiatric evaluation have not been conducted. Therefore, counseling for these CNV is challenging even if the evidence supporting the pathogenicity of these CNV is strong in the research literature. In research studies, the “pathogenicity” of a given CNV is typically made based on the statistical value from population-based case and control studies. Translation of these research findings into the clinic and counseling families is clearly not straightforward if the CNV are inherited from healthy parents.

A novel CNV containing histone methyltransferase associated with ASD and ID

The finding of a de novo CNV loss in the 1q21.3 region is novel and has not been reported in the literature. There are 10 genes (ARNT, SETDB1, CERS2, ANXA9, FAM63A, PRUNE, CDC42SE1, BNIPL, MLLT11, C1orf56) mapped in the deleted interval. However, the functions for these genes, except CERS2 and SETDB1, are either not related to brain function or have not been characterized. CERS2 encodes ceramide synthase, and ceramides form the lipid backbone of all complex sphingolipids. Cers2 homozygous mutant mice have a short life span, liver dysfunction, and generalized and symmetrical myoclonic jerks [15]. The defects in ceramide metabolism are implicated in a list of neurometabolic diseases. However, these diseases exclusively follow autosomal recessive inheritance in humans and the clinical relevance of the haploinsufficiency of CERS2 is probably not significant unless there is a pathogenic mutation in other allele that is missed. On the other hand, deletion of SETDB1, a histone methyltransferase, is particularly interesting. SETDB1 is a promising candidate gene for ASD/ID because of its role in epigenetic modification and brain function [26]. In mice, Setdb1 deficiency modifies the neuronal phenotypes caused by deficiency of the Rett syndrome protein MeCP2[27] and regulates the expression of NMDA receptor 2B[28], a gene implicated in cognitive function and epilepsy. Functional studies in vitro strongly support a role for Setdb1 in synaptic development and function [27, 28]. In humans, an in-frame 3 bp deletion in SETDB1 was reported in an individual with ASD[29]. Furthermore, de novo loss of function (LOF) or likely gene-disrupting mutations (LGD) in a list of genes encoding chromatin modifier proteins have been identified in individuals with ASD from several large scale whole exome sequencing studies[30]. Although pathogenic mutations in SETDB1 have not been identified in these studies, the LOF and LGD mutations in genes regulated by SETDB1 are frequently found in ASD individuals. These data provide evidence supporting the pathogenicity of haploinsufficiency of SETDB1 in ASD and ID.

Clinical relevance of multiple CNV in clinic

We found 7 families (6.1%) with a complex pattern of multiple CNV, illustrating the challenges related to interpretation of the clinical relevance of CNV. For example, our case #33 that has an inherited paternal duplication of 15q11.2-q13.1 and de novo deletion of 5q35.3 in one but not the other affected sibling is particularly interesting. While maternal duplication of 15q11-q13 has been consistently implicated in severe ASD and ID [31, 32], the clinical relevance of paternal duplication of 15q11-q13 is much less clear and has been associated with a wide range of clinical presentations from normal to mild or moderate ASD and ID [31, 33]. In this family, the healthy father carried a de novo 15q11.2-q13.1 duplication that presumably derived from the paternal chromosome 15. It is difficult to establish that the paternal duplication of 15q11.2-q13.1 is the cause of ASD for the severely affected sibling based on the available data in the literature. However, the presence of the de novo 5q35.3 deletion may support a two hit model as suggested by others[34, 35]; the combination of the paternal duplication of 15q11.2-q13.1 and 5q35.3 deletion may be responsible for the symptoms in the more severely affected sibling. The 5q35.3 deletion contains MGAT1, a gene encoding a N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I and involving protein glycosylation. Although MGAT1 has not been associated with any genetic disease, deficiency of many other enzymes required for glycosylation cause a group of rare disorders, congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG), in which developmental delay is an almost universal feature. Because all known CDG follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, the significance of haploinsufficiency of MGAT1 is not clear. However, in a two hit model, the plausible hypothesis is that the deletion of 5q35.3 may modify the paternal duplication of 15q11-q13 and contribute to the more severe clinical presentation of the older sibling. Because of the rarity of these CNV, it is challenging, if not impossible, to test this hypothesis directly in humans.

Alternatively, both CNV of 15q11.2-q13.1 and 5q35.3 are not pathogenic, and other genetic defects, such as point mutations in another gene or genes, or epigenetic factors may be responsible for the clinical presentation in the older sibling while the cause for young sibling remains to be identified.

The 2 cases with 3 CNV, that both involve 22q13.3 PMS region, are also interesting. In the case #37, the 1p31.1 deletion is inherited from the unaffected mother. The inheritance patterns for 16p13.2 and 22q13.3 could not be determined because the father was unavailable. The deletion of 22q13.3 is a definitive cause for ASD and deletion of the SHANK3 gene specifically is a major cause of the Phelan-McDermid syndrome. The de novo duplication of 16p13.2 has been associated with ASD in a recent report [36] and also found rarely in a control population[37]. The patient's overall clinical presentation is consistent with PMS. Surprisingly, the patient's social interaction and communication are quite intact. Because ASD and impaired social interaction and communication are prominent features associated with PMS[38-40], this raised an interesting question whether her unique clinical phenotypes are modified by CNV of 1p13.3 and 16p13.2. The deletion of 1p13.1 was inherited from the patient's unaffected mother and has not been associated with any disease phenotype; therefore, it is less likely that this deletion will have a major role in her clinical presentation. An interesting question is whether the combination of 22q13.3 deletion and 16p13.2 duplication are responsible for her unique behavioral features, which are not apparently more severe than in cases carrying only one of these CNV. Alternatively, it can be hypothesized that the 1p31.1 deletion may modify the contribution of the deletion of 22q13.3 and the duplication of 16p13.2 to her presentation, or a more provocative question is whether CNV of 16p13.2 and 1p31.1 may function as a protective allele to SHANK3 deficiency in 22q13.3 CNV.

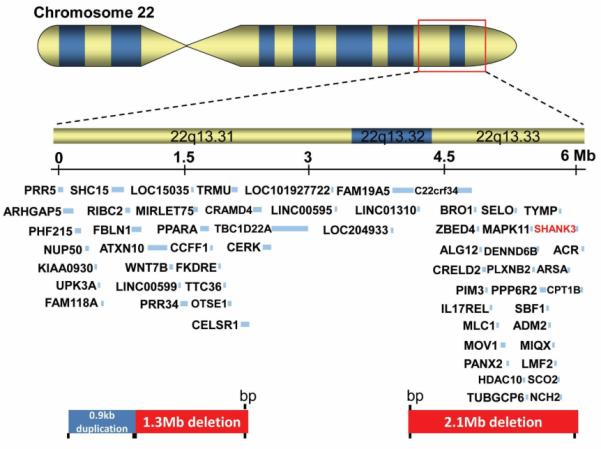

A practical algorithm and the challenge of interpreting and counseling CNV findings in clinic

The clinical benefit and technical merit of using genome wide CNV analysis to detect many well-defined deletion and duplication syndromes are clear in both research and clinical literature[10, 2]. However, there are few studies that systematically address the challenges of interpreting the CNV results and the accompanying counseling issues including the psychologic and economic impact to families. For newly-identified CNV associated with ASD and ID, the evidence supporting their pathogenicity is mostly drawn from population-based studies. In the population-based research studies, while variable penetrance and pleotropic expressivity have been frequently observed and extensively discussed, clinical decision-making for individual cases is usually not addressed during the research phase of the studies. However, the situation is different for clinical CNV analysis because physicians will have to interpret the findings and counsel the family accordingly and in a timely manner. For this reason, we propose a practice algorithm for interpreting CNV findings in clinic (Figure 5). The counseling and classification of pathogenic CNV that are known to cause well defined deletion or duplication syndromes such as Angelman and Phelan-McDermid syndromes are straight forward. However, for the examples of 16p11.2 deletion, 15q11-q13 paternal duplication, and 15q13.3 deletion, the clinical decision making and counseling was challenging. Evidence from research literature clearly supports the classification of these CNV to be pathogenic. However, because these CNV can be inherited from an apparently healthy parent or de novo, and have variable penetrance or pleotropic effects, the interpretation of pathogenicity and counseling in the family with a severely affected proband and CNV inherited from a healthy parent is challenging. The counseling in prenatal setting is even more complex. This is best illustrated in case #10 with the deletion of 16p11.2[41].

Figure 5.

The proposed practice algorithm for interpreting CNV in clinic

Because the deletion of 16p11.2 has been also found in healthy individuals in low frequency, the prenatal counseling for this family has been challenging. As illustrated in our findings from a small number of cases in this cohort, the clinical CNV analysis will discover a majority of CNV that are rare and novel but they fall into the second or third categories as described above. Families may have to deal with the uncertainty or psychological stress of being informed that their child has a CNV of unknown clinical relevance or the result is difficult to interpret. In other cases, there may also be an economic impact. Unfortunately, these questions have not been addressed systematically despite CNV analysis having been performed in clinics routinely for about a decade. A more comprehensive study is clearly warranted in this direction including assessing the long term psychosocial impact of this testing to the families and patients.

Conclusion

Our data of CNV analyses from a cohort of 115 individuals with ASD/ID/DD referred to the Autism Genetics Clinic support the clinical utilization of CNV analysis. The overall positive rate for pathogenic CNV in this cohort is 18.3% but the clinical relevance of a significant number of CNV remains unclear. Our novel finding of deletion of SETDB1 in a patient with classical autism provides the further support for the role of chromatin modifiers in the etiology of ASD. Our finding of more than one rare and novel CNV in individuals adds to the complexity for interpreting the clinical relevance of these CNV. Despite the strong evidence supporting the pathogenicity of many CNV from research studies, the clinical significance of these CNV, and counseling about these findings in clinics remain challenging because of variable penetrance and pleotropic effects. Further studies may be warranted to fully evaluate medical, social, psychological, and economical benefits related to CNV analysis in the clinical evaluation of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects and case review

A total of 165 patients carrying a diagnosis of ASD and/or ID and DD were recruited consecutively from the Autism Genetics Clinic at Duke Children's Hospital from 2010-2014. Only the medical records for the cases with positive CMA were then reviewed. The age of these patients ranged from 18 months to 15.1 years. The diagnosis of ASD/DD/ID was made by each patient's referring clinician. Additional study was conducted for selected cases. The study was approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of their individual details and accompanying images in this manuscript. The consent form is held by YHJ and available at Duke University.

Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA) or Array-based Comparative Genomic Hybridization (Array-CGH)

CMA or Array-CGH was performed in one of the following clinical laboratories: the Duke University Cytogenetics Laboratory (Durham, NC), the Baylor College of Medicine Molecular Genetics Laboratory (Houston, TX), or LabCorp genetics laboratory (Research Triangle Park, NC). The following array platforms were used: the Duke University Cytogenetics Laboratory, BlueGnome CytoChip v2 [BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome) array](Illumina, San Diego, CA), the Duke University Cytogenetics Laboratory and LabCorp, Affymetrix human genome-wide SNP 6.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and the Baylor College of Medicine Molecular Genetics Laboratory Affymetrix Cytoscan HD array [42, 43]. The BlueGnome CytoChip v2 consists of ~4400 BAC clones representing greater than 90 clinically defined syndrome loci and all 41 unique subtelomeric regions. The Affymetrix human genome-wide SNP 6.0 array consists of 1.8 million genetic markers at a median inter-marker spacing of less than 700 nucleotides. Approximately half of these markers provide SNP genotype calls in addition to copy number state information. The Affymetrix Cytoscan HD array consists of nearly 2.7 million genetic markers incorporating 743,304 SNP probes as well as 1,953,246 non-polymorphic CNV probes. For the array hybridization, 500ng of genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood was enzymatically digested, amplified, and purified. Purified products were fragmented, labeled, and hybridized to the array. After washing (Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450), arrays were scanned (Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000) and the analysis was performed using the Affymetrix Genotyping Console 3.0.2 software. CNV calling and interpretation were extracted from the reports from the individual clinical laboratories.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was performed using BAC clone RP11-11. as a probe for the 1q21.3 region, RP11-451H23 (BlueGenome) as a probe for the 5q35.3 region and the Abbott Molecular dual color probe for the Prader-Willi syndrome critical region (SNRPN) at 15q11-q13 and a distal locus for identification of chromosome 15.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

QX and XX were supported by grants 81371270 from the National Science Foundation of China (XX). QX is supported by grants 15411967900 from Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission. PW was supported Autism Speaks, YHJ is supported by National Institute of Health Grants: MH098114, HD077197, and MH104316.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

QX and YHJ conceived and conducted the study; IG, HL, CR contributed CNV analysis, WPP, AM, YHJ contributed to review the medical records, QX, JG, XX,WPW, AM, and YHJ wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Freeman JL, Perry GH, Feuk L, et al. Copy number variation: new insights in genome diversity. Genome Res. 2006;16:949–61. doi: 10.1101/gr.3677206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conrad DF, Pinto D, Redon R, et al. Origins and functional impact of copy number variation in the human genome. Nature. 2010;464:704–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ, Professional P, Guidelines C. Clinical genetics evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders: 2013 guideline revisions. Genet Med. 2013;15:399–407. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. American journal of human genetics. 2010;86:749–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning M, Hudgins L, Professional P, Guidelines C. Array-based technology and recommendations for utilization in medical genetics practice for detection of chromosomal abnormalities. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2010;12:742–5. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f8baad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaudet AL. The utility of chromosomal microarray analysis in developmental and behavioral pediatrics. Child development. 2013;84:121–32. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betancur C. Etiological heterogeneity in autism spectrum disorders: more than 100 genetic and genomic disorders and still counting. Brain Res. 2011;1380:42–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devlin B, Scherer SW. Genetic architecture in autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:229–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagoo GS, Little J, Higgins JP. Systematic reviews of genetic association studies. Human Genome Epidemiology Network. PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminsky EB, Kaul V, Paschall J, et al. An evidence-based approach to establish the functional and clinical significance of copy number variants in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2011;13:777–84. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31822c79f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas NS, Durkie M, Potts G, et al. Parental and chromosomal origins of microdeletion and duplication syndromes involving 7q11.23, 15q11-q13 and 22q11. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2006;14:831–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piard J, Philippe C, Marvier M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a large family with an interstitial 15q11q13 duplication. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2010;152A:1933–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Y, Dies KA, Holm IA, et al. Clinical genetic testing for patients with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e727–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coe BP, Witherspoon K, Rosenfeld JA, et al. Refining analyses of copy number variation identifies specific genes associated with developmental delay. Nature genetics. 2014;46:1063–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-David O, Pewzner-Jung Y, Brenner O, et al. Encephalopathy caused by ablation of very long acyl chain ceramide synthesis may be largely due to reduced galactosylceramide levels. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:30022–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.261206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarraf SA, Stancheva I. Methyl-CpG binding protein MBD1 couples histone H3 methylation at lysine 9 by SETDB1 to DNA replication and chromatin assembly. Molecular cell. 2004;15:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordgren A, Arver S, Kvist U, Carter N, Blennow E. Trisomy 5q12-->q13.3 in a patient with add(13q): characterization of an interchromosomal insertion by forward and reverse chromosome painting. American journal of medical genetics. 1997;73:351–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19971219)73:3<351::aid-ajmg23>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faivre L, Gosset P, Cormier-Daire V, et al. Overgrowth and trisomy 15q26.1-qter including the IGF1 receptor gene: report of two families and review of the literature. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2002;10:699–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelante L, Croce AI, Grifa A, Notarangelo A, Calvano S. Interstitial “de novo” tandem duplication of 7(q31.1-q35): first reported case. Ann Genet. 2003;46:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3995(03)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kant SG, Kriek M, Walenkamp MJ, et al. Tall stature and duplication of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor gene. European journal of medical genetics. 2007;50:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Beri S, et al. Molecular mechanisms generating and stabilizing terminal 22q13 deletions in 44 subjects with Phelan/McDermid syndrome. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nature genetics. 2007;39:25–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar M, Iliadi KG, Leventis PA, Schachter H, Boulianne GL. Neuronal expression of Mgat1 rescues the shortened life span of Drosophila Mgat11 null mutants and increases life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9677–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004431107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Repetto GM, White LM, Bader PJ, Johnson D, Knoll JH. Interstitial duplications of chromosome region 15q11q13: clinical and molecular characterization. American journal of medical genetics. 1998;79:82–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980901)79:2<82::aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miles JH. Autism spectrum disorders--a genetics review. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2011;13:278–94. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ff67ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan SL, Nishi M, Ohtsuka T, et al. Essential roles of the histone methyltransferase ESET in the epigenetic control of neural progenitor cells during development. Development. 2012;139:3806–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.082198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Y, Matevossian A, Guo Y, Akbarian S. Setdb1-mediated histone H3K9 hypermethylation in neurons worsens the neurological phenotype of Mecp2-deficient mice. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1088–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Y, Jakovcevski M, Bharadwaj R, et al. Setdb1 histone methyltransferase regulates mood-related behaviors and expression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7152–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1314-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cukier HN, Lee JM, Ma D, et al. The expanding role of MBD genes in autism: identification of a MECP2 duplication and novel alterations in MBD5, MBD6, and SETDB1. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2012;5:385–97. doi: 10.1002/aur.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iossifov I, O'Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–21. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook EH, Jr., Lindgren V, Leventhal BL, et al. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. American journal of human genetics. 1997;60:928–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depienne C, Moreno-De-Luca D, Heron D, et al. Screening for genomic rearrangements and methylation abnormalities of the 15q11-q13 region in autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:349–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolton PF, Dennis NR, Browne CE, et al. The phenotypic manifestations of interstitial duplications of proximal 15q with special reference to the autistic spectrum disorders. American journal of medical genetics. 2001;105:675–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girirajan S, Rosenfeld JA, Cooper GM, et al. A recurrent 16p12.1 microdeletion supports a twohit model for severe developmental delay. Nature genetics. 2010;42:203–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leblond CS, Kaneb HM, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. Dissection of genetic factors associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Experimental neurology. 2014;262(Pt B):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders SJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Hus V, et al. Multiple recurrent de novo CNVs, including duplications of the 7q11.23 Williams syndrome region, are strongly associated with autism. Neuron. 2011;70:863–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uddin M, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Walker S, et al. A high-resolution copy-number variation resource for clinical and population genetics. Genet Med. 2014 doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarasua SM, Boccuto L, Sharp JL, et al. Clinical and genomic evaluation of 201 patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Hum Genet. 2014;133:847–59. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soorya L, Kolevzon A, Zweifach J, et al. Prospective investigation of autism and genotypephenotype correlations in 22q13 deletion syndrome and SHANK3 deficiency. Molecular autism. 2013;4:18. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarasua SM, Dwivedi A, Boccuto L, et al. Association between deletion size and important phenotypes expands the genomic region of interest in Phelan-McDermid syndrome (22q13 deletion syndrome). Journal of medical genetics. 2011;48:761–6. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller DT, Chung W, Nasir R, et al. In: 16p11.2 Recurrent Microdeletion. Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle (WA): 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conlin LK, Thiel BD, Bonnemann CG, et al. Mechanisms of mosaicism, chimerism and uniparental disomy identified by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Human molecular genetics. 2010;19:1263–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaaf CP, Wiszniewska J, Beaudet AL. Copy number and SNP arrays in clinical diagnostics. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-092010-110715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]