Abstract

Alhagi species are well known in Iran (locally known as Khar Shotor) and other parts of Asia as a popular folk medicine. Recent research has shown extensive pharmacological effects of these species. This paper is a comprehensive review of the phytopharmacological effects and traditional uses of Alhagi species and their active constituents with special attention to the responsible mechanisms, effective dosages and routes of administration. The Alhagi species studied in this paper include: A. maurorum, A. camelorum, A. persarum, A. pseudoalhagi, and A. kirgisorum. In order to include all the up to date data, the authors went through several databases including the Web of Science, Embase, etc. The findings were critically reviewed and sorted on the basis of relevance to the topic. Tables have been used to clearly present the ideas and discrepancies were settled through discussion. Alhagi species have significant biomedical properties which can be exploited in clinical use. Proantocyanidin isolated from A. pseudoalhagi has significant biochemical effects on blood factors. Among Alhagi species, A. camelorum and A. maurorum possess the highest anti-microbial activity. Most of the effects observed with A. maurorum are dose-dependent. This paper indicates with emphasis that Alhagi species are safe and rich sources of biologically active compounds with low toxicity. Since DNA damage has been observed following the ingestion of specific concentrations of A. pseudalhagi, care should be taken during administration of the plant for therapeutic use. Further studies are required to confirm the safety and quality of these plants to be used by clinicians as therapeutic agents.

Keywords: A. camelorum, A. persarum, Alhagi maurorum, folk medicine, mechanistic review

Introduction

The genus Alhagi includes a number of species, the most important of which are A. maurorum, A. camelorum, and A. persarum. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and the most inclusive review paper prepared so far, regarding the traditional usages and pharmacological effects of Alhagi species [Tables 1 and 2] with special emphasis on the mechanisms involved [Table 3]. We have compiled the most effective dosages responsible for each effect based on previous pharmacological studies. This is to provide a reliable source for other researchers. The findings were critically reviewed and sorted on the basis of relevance to the topic. Tables were used to clearly present the ideas and discrepancies were settled through discussion.

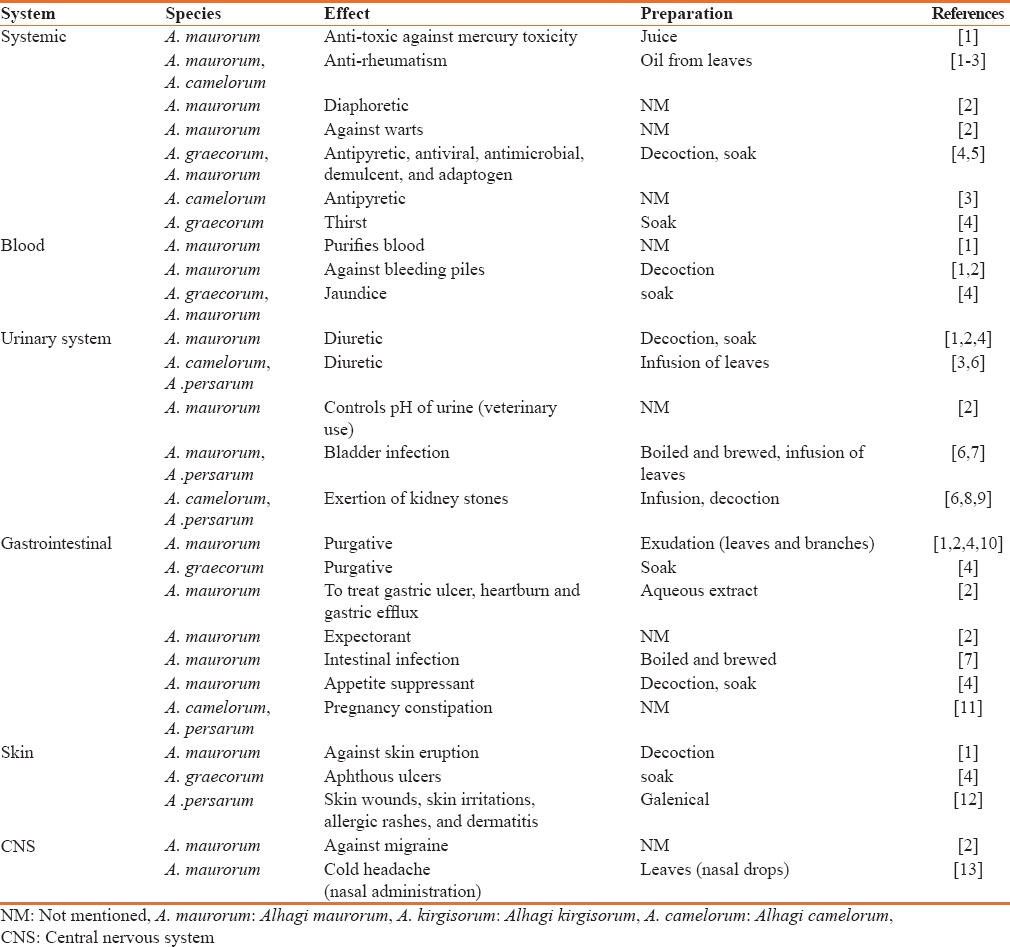

Table 1.

Traditional uses of Alhagi species

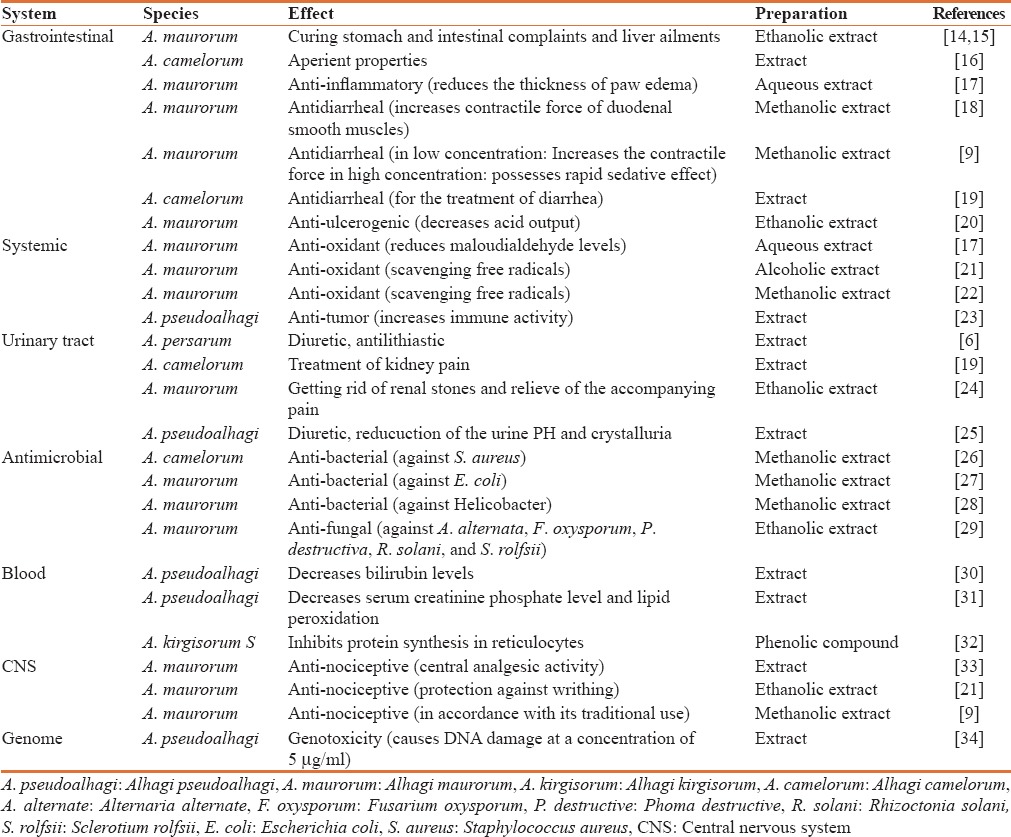

Table 2.

Pharmacological effects of Alhagi species

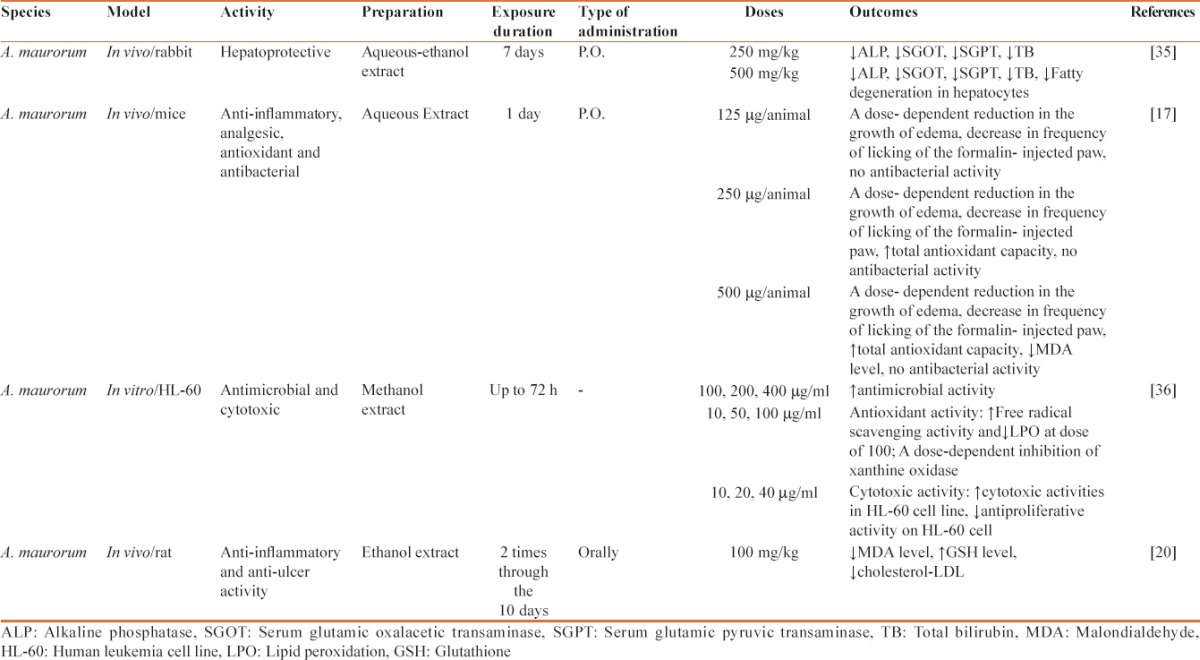

Table 3.

Detailed presentation of some previously proven phyto-pharmacological properties of Alhagi species

Approach to Systematic Review

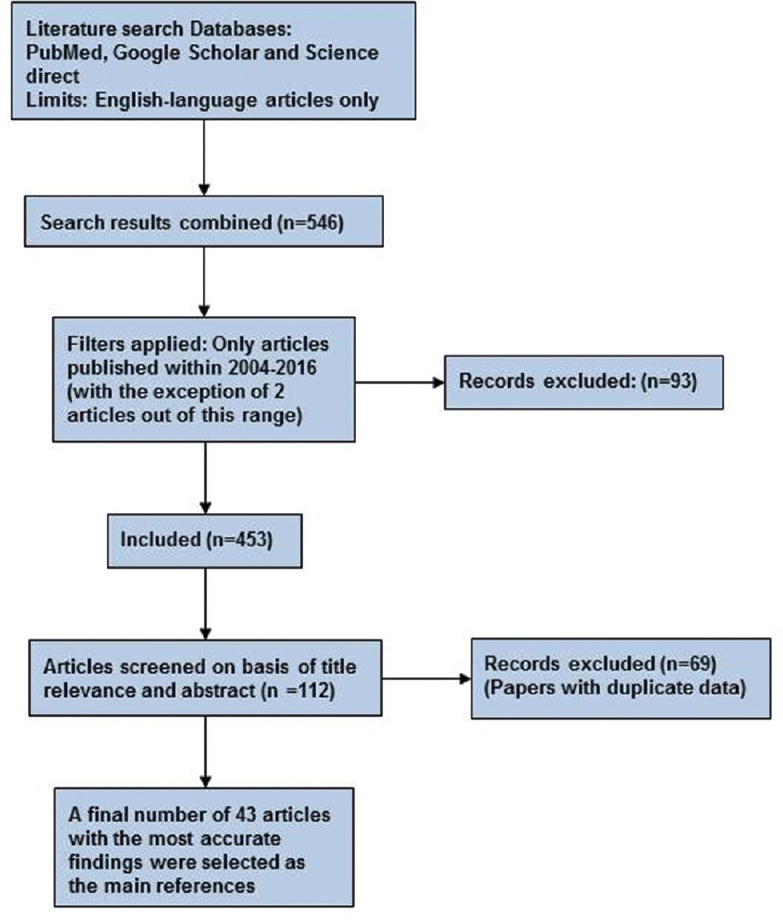

An online literature search was performed on Web of science, Embase, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases for the key words of Alhagi, pharmacol, etc., with a time limit of papers published from 2004 up to November 2015 in accordance to PRISMA guidelines. The search strategy is illustrated in a flow diagram [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic literature search strategy

Gastrointestinal Effects

Local inhabitants of India use A. maurorum to cure stomach and intestinal complaints including diarrhea, dyspepsia, constipation, bloating, diminished appetite and also for the treatment of liver inflammation. Major chemical compounds found in A. maurorum are b-sitosterol, cinnamic acid, coumaric acid, hydroxybenzoic acid.[14] In Arabian traditional medicine A. maurorum is used for the prevention and treatment of liver ailments (such as jaundice), lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting and other stomach disorders. A study on the ethno-veterinary usage of A. camelorum of Greater Cholistan desert of Pakistan indicated that A. camelorum has aperient properties in animals.[16] Investigations on the hepato-protective effect A. maurorum showed that Ethanolic Extract of this plant at the doses of 250 and 500 mg/kg failed to inhibit the raised biomarkers (SGOT, SGPT, ALP and bilirubin levels).[15]

Anti-inflammatory Effects

One study showed that the aqueous extract of A. maurorum may be useful in protection against inflammatory diseases, especially if free radicals are a part of its pathophysiology. The extract significantly reduced the thickness of paw edema induced by formalin in a dose-dependent manner.[17] It has been shown that A. maurorum Medic is a more potent anti-inflammatory agent in comparison to diclofenac sodium (30 mg/kg), a conventional anti-inflammatory drug.[21]

Antioxidant Effects

The aqueous extract of A. maurorum exerts antioxidant effects by reducing malondialdehyde levels.[17] The alcoholic extract of A. maurorum Medic has also shown antioxidant activity by scavenging free radicals at different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 mg/ml).[21] The leaf extract has higher antioxidant potential than the flower extract due to its higher phenolic contents.[22] Three important antioxidant flavonoids have been isolated from A. maurorum which include isorhamnetin-3-O-[-alpha-l-rhamnopyranosyl- (1-3)]- beta- D-glucopyranoside, 3’-O-methylorobol and Quercetin 3-O-beta-d-glucopyranoside.[37]

Urinary Tract Effects

In Iranian traditional medicine, a glass of A. persarum is taken before meals to treat urinary tract infections. It is also used as an effective diuretic and anti-lithiastic agent.[6] An ethno-pharmacological survey in the north of Iran showed that the concentrated decoction of A. camelorum was used among Iranians for the treatment of kidney pain.[19] It was shown in a study that the ethanolic extract of the roots of A. maurorum possesses spasmolytic and ureter relaxing activity. It is also effective in relieving the pain resulting from renal stones (contraction of the ureter).[24] The same anti-lithiastic effect has been elicited from 2% aqueous acetic acid extract of A. maurorum powdered roots.[38] In addition to its diuretic effect, A. pseudalhagi can reliably reduce the urine pH for a long time. This species of Alhagi also has the potential to reduce crystalluria.[25]

Anti-microbial Effects

A. camelorum has been long used by native Iranians in the treatment of infectious diseases.[27] A study indicates that the methanolic extract of A. camelorum has antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, supporting its traditional use by Iranians. Methanolic extract of A. maurorum used in folklore Iranian medicine has antibacterial activity against two strain of Escherichia coli at a concentration of 20 mgmL-1.[26]

In an in vitro study on the anti-helicobacter activity of some Egyptian plants, the extracts of A. maurorum exhibited the strongest activity. This effect of the plant was assessed after determination of its MIC by agar diffusion method.[28]

Another in vitro study in Saudi Arabia on the anti-fungal activity of A. maurorum showed that the ethanolic extract of this plant is effective against Alternaria alternata, Fusarium oxysporum, Phoma destructiva, Rhizoctonia solani, and Sclerotium rolfsii at a concentration of 9%.[29]

Biochemical Effects

An in vitro study revealed that A. pseudalhagi extract may decrease bilirubin levels by cathartic effect or activation of liver enzymes.[30] Another study showed that intravenous administration of proantocyanidin isolated from A. pseudoalhagi diminishes serum creatinine phosphate levels and lipid peroxidation both in the myocardium and serum in animals with experimental myocardial infarction.[31] A survey in 1990 indicated that a phenolic compound from A. kirgisorum S. (Polyproanthocyanidin) impressively inhibited protein synthesis in rabbit reticulocyte.[32] A. camelorum also has therapeutic potential in the treatment of diabetes and other chronic diseases. The suggested mechanism of action is a-Glucosidase inhibition.[23]

Anti-diarrhoeal Effects

A. maurorum and a concentrated decoction of A. camelorum have been used in traditional medicine of Egypt and Iran for the treatment of diarrhea.[9,19] In an in vitro study, methanol extract of the aerial parts of A. maurorum at a dose of 200 mg/kg (IP) exhibited a significant anti-diarrheal effect against castor oil-induced diarrhea, and also increased the contractile force of duodenal smooth muscles in rabbits.[18] In another study it was shown that the oral administration of the extract can exert anti-diarrheal effects as well. The suggested mechanism of action in low concentrations (0.4 mg/ml) is increasing the contractile force. Higher concentrations (3.2 mg/ml) caused a rapid sedative effect. The sedative effect induced by A. maurorum (at higher doses) appeared to be due to calcium channel blocking effect.[19]

Anti-ulcerogenic Effects

In one study, six main flavonoid glycosides were isolated from the ethanol extract of A. maurorum. The flavonoids were identified as kaempferol, chrysoeriol, isorhamnetin, chrysoeriol-7-O-xylosoid, kaempferol-3-galactorhamnoside and isorhamnetin3-O-b-D-apio-furanosyl (1-2) b-D-galactopyranoside. The total extract (300 and 400 mg/kg) and two of the isolated compounds (chrysoeriol 7-O-xylosoid and kaempferol-3-galactorhamnoside, 100 mg/kg each) showed a very promising anti-ulcerogenic activity with curative ratios of 66.31%, 69.57%, 75.49%, and 77.93%, respectively.[39] It was also shown that the ethanolic extract of A. maurorum in combination with ranitidine can be used in rats to protect them against the side effects of aspirin administered two times through 10 days. Decreased acid output as a result of the plant extract and ranitidine administration was suggested as the mechanism responsible for this effect.[20]

Anti-tumoral Effects

Abnormal Savda Munziq (ASMq), a traditional Uyghur medicinal herbal preparation from the Xinjiang region of China, has long been used in Traditional Uyghur Medicine for the treatment of complex diseases such as tumors. ASMq is composed of ten medicinal herbs one of which is A. pseudalhagi. The anti-tumour activity of this compound has been pharmacologically proven with a suggested mechanism of increasing immune activity.[40]

Anti-nociceptive Effects

A. maurorum has been traditionally used by Egyptians to relieve pain.[9] The plant has been shown to possess central analgesic effect at the dose of 500 mg/kg. This activity is mediated through opiodergic receptors.[33] In one study, ethanol extracts of A. maurorum Medic was shown to exert significant protection against writhing.[21]

Genotoxicity

A. pseudalhagi which has been long used by traditional Iranians has been shown to cause DNA damage at a concentration of 5 μg/ml, and a concentration less than 5 μg/ml is proven to be safe.[31]

Implications in Traditional Medicine

A multitude of preparations made from Alhagi species have been acknowledged in [Iranian] traditional medicine. These preparations have been beneficial in treating a number of disorders involving different systems. A. maurorum has been used in the treatment of gastric ulcers,[2] intestinal tract infections,[7] as an expectorant,[2] appetite suppressant[4] and as a purgative.[1,2] A. camelorum and A. persarum also have been used in ameliorating pregnancy constipation.[11] In dermatologic conditions, A. maurorum, A. graceum and A. persarum have been applied on skin eruptions,[1] aphtous ulcers[4] and skin wounds and inflammations[12] respectively. Interestingly, A. maurorum has antimigraine properties[2] and has been further administered nasally to soothe headache due to colds.[13] In the urinary system, A. maurorum, A. camelorum and A. persarum can cause diuresis[1,2,3,4,6] and aid in passing renal stones.[6,8,9] In addition, boiled infusions of A. maurorum and A. persarum act as a urinary disinfectant.[6,7] Moreover, A. maurorum is proven to be protective in various other conditions such as, mercury poisoning and rheumatism[1,2,3] and is active against microbial and viral organism.[2,4,5] These enormous therapeutic effects of Alhagi species indicate their great potential as traditional remedies and should inspire researchers to further investigate this marvelous genus.

Conclusion

Our aim of conducting this study was to present a compilation of evidence-based comprehensive information regarding the traditional usage of Alhagi species with special attention to their previously proven pharmacological effects and mechanisms. Since there are a vast number of studies in the literature conducted on Alhagi species, this paper can provide almost all the required information as a comprehensive reference for further studies that might be performed by other researchers in the future. As it is evident from this study, Alhagi species possess a wide range of pharmacological effects, the most important of which include: gastrointestinal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects among many others. These species have been traditionally used for renal stones, stomach complaints, to relieve pain, and to reduce paw edema in veterinary medicine, etc, Proantocyanidin isolated from A. pseudalhagi has significant biochemical effects on blood factors. Among Alhagi species, A. camelorum and A. maurorum possess the highest anti-microbial activity. Most of the effects observed with A. maurorum have had a dose-dependent behaviour. The doses at which the best effects have been recorded in different systems following the administration of A. maurorum, ranged between 100 to 500 mg/kg for in vivo studies. Since DNA damage has been observed following the ingestion of specific concentrations of A. pseudalhagi, care should be taken during administration of the plant for therapeutic use. A vast number of pharmacological and medicinal properties of Alhagi species make these plants a desirable source for development of new drugs; however, more studies are required to be conducted to specify the precise quality and safety of the plants to be further used by clinicians and other healthcare professionals for therapeutic purposes.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is related to the project NO. 1395/76874 From Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. We also appreciate the “Student Research Committee” and “Research and Technology Chancellor” in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Iqbal H, Sher Z, Khan ZU. Medicinal plants from salt range Pind Dadan Khan, district Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:2157–68. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad N, Bibi Y, Saboon, Raza I, Zahara K, Idrees S, et al. Traditional uses and pharmacological properties of Alhagi maurorum: A review. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2015;5:856–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behzad S, Pirani A, Mosaddegh M. Cytotoxic activity of some medicinal plants from hamedan district of Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13(Suppl):199–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amiri MS, Joharchi MR, Taghavizadehyazdi ME. Ethno-medicinal plants used to cure jaundice by traditional healers of Mashhad, Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:157–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamedi A, Farjadian S, Karami MR. Immunomodulatory properties of Taranjebin (camel's thorn) manna and its isolated carbohydrate macromolecules. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015;20:269–74. doi: 10.1177/2156587215580490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikaili P, Shayegh J, Asghari MH. Review on the indigenous use and ethnopharmacology of hot and cold natures of phytomedicines in the Iranian traditional medicine. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(2 Suppl):S1189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahmani M, Saki K, Shahsavari S, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Sepahvand R, Adineh A. Identification of medicinal plants effective in infectious diseases in Urmia, Northwest of Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2015;5:858–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahmani M, Zargaran A. Ethno-botanical medicines used for urinary stones in the Urmia, Northwest Iran. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7:657–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudaib M, Mohammad M, Bustanji Y, Tayyem R, Yousef M, Abuirjeie M, et al. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Jordan, Mujib nature reserve and surrounding area. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atta AH, Abo EL-Sooud K. The antinociceptive effect of some Egyptian medicinal plant extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;95:235–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashem Dabaghian F, Taghavi Shirazi M, Amini Behbahani F, Shojaee A. Interventions of Iranian traditional medicine for constipation during pregnancy. J Med Plants. 2015;14:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mamedov N, Gardner Z, Craker LE. Medicinal plants used in Russia and Central Asia for the treatment of selected skin conditions. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2004;11:191–222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghorbanifar Z, Delavar Kasmaei H, Minaei B, Rezaeizadeh H, Zayeri F. Types of nasal delivery drugs and medications in Iranian traditional medicine to treatment of headache. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e15935. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.15935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hameed M, Ashraf M, Al-Quriany F, Nawaz T, Ahmad MS, Younis A, et al. Medicinal flora of the cholistan desert: A review. Pak J Bot. 2011;43:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alqasoumi SI. Isolation and chemical structure elucidation of hepatoprotective constituents from plants used in traditional medicine in Saudi Arabia. King Saudi University; 2007. p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan FM. Ethno-veterinary medicinal usage of flora of greater Cholistan desert (Pakistan) Pak Vet J. 2009;29:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neamah NF. A pharmacological evaluation of aqueous extract of Alhagi maurorum. Glob J Pharmacol. 2012;6:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutiérrez SP, Sánchez MA, González CP, García LA. Antidiarrhoeal activity of different plants used in traditional medicine. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:2988–94. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirdeilami SZ, Barani H, Mazandarani M, Heshmati GA. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Maraveh Tappe region, North of Iran. Iran J Plant Physiol. 2011;2:327–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaker E, Mahmoud H, Mnaa S. Anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcer activity of the extract from Alhagi maurorum (camelthorn) Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2785–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awaad AS, El-Meligy R, Qenawy S, Atta A, Soliman GA. Anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and antipyretic effects of some desert plants. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2011;15:367–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laghari AH, Ali Memon A, Memon S, Nelofar A, Khan KM, Yasmin A. Determination of free phenolic acids and antioxidant capacity of methanolic extracts obtained from leaves and flowers of camel thorn (Alhagi maurorum) Nat Prod Res. 2012;26:173–6. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.538846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandeya KB, Tripathi IP, Mishra MK, Dwivedi N, Pardhi Y, Kamal A, et al. A critical review on traditional herbal drugs: An emerging alternative drug for diabetes. Int J Org Chem. 2013;3:1–22. Doi: 10.4236/ijoc.2013.31001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marashdah M, Al-Hazimi H. Pharmacological activity of ethanolic extract of Alhagi maurorum roots. Arabian J Chem. 2010;3:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaybullaev A, Kariev S. Phytotherapy of calcium urolithiasis with extracts of medicinal plants: Changes of diuresis, urine pH and crystalluria. Appl Technol Innov. 2012;7:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonjar GS. Screening for antibacterial properties of some Iranian plants against two strains of Escherichia coli. Asian J Plant Sci. 2004;3:310–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonjar GS. Inhibition of three isolates of Staphylococcus aureus mediated by plants used by Iranian native people. J Med Sci. 2004;4:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramadan MA, Safwat N. Antihelicobacter activity of a flavonoid compound isolated from Desmostachya bipinnata. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3:2270–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Askar AA. In vitro antifungal activity of three Saudi plant extracts against some phytopathogenic fungi. J Plant Prot Res. 2012;52:458–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nabavizadeh S, Nabavi M. The effect of herbal drugs on neonatal jaundice. Iran J Pharm Res. 2010;3:39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khushbaktova Z, Syrov V, Kuliev Z, Bashirova N, Shadieva Z, Gorodeyskaia E, et al. The effect of proanthocyanidins from Alhagi pseudoalhagi (MB) Desv on the course of experimental myocardial infarct. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 1991;55:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smailov SK, Mukhamedzhanov BG, Lee AV, Iskakov BK, Denisenko ON. An inhibitor of protein synthesis initiation from Alhagi kirgisorum S. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:99–101. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81448-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almeida R, Navarro D, Barbosa-Filho J. Plants with central analgesic activity. Phytomed. 2001;8:310–22. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Etebari M, Ghannadi A, Jafarian-Dehkordi A, Ahmadi F. Genotoxicity evaluation of aqueous extracts of Cotoneaster discolor and Alhagi pseudalhagi by comet assay. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(Suppl 2):S237–41. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rehman JU, Aktar N, Khan MY, Ahmad K, Ahmad M, Sultana S, et al. Phytochemical screening and hepatoprotective effect of Alhagi maurorum boiss (Leguminosae) against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rabbits. Trop J Pharm Res. 2015;14:1029–34. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sulaiman GM. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of methanol extract of Alhagi maurorum. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:1548–57. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad S, Riaz N, Saleem M, Jabbar A, Nisar-Ur-Rehman M, Ashraf M. Antioxidant flavonoids from Alhagi maurorum. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2010;12:138–43. doi: 10.1080/10286020903451724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marashdah M, Farraj A. Pharmacological activity of 2% aqueous acetic acid extract of Alhagi maurorum roots. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2010;14:247–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Awaad Amani A, Maitland D, Soliman G. Antiulcerogenic activity of Alhagi maurorum. Pharm Biol. 2006;44:292–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aikemu A, Umar A, Yusup A, Upur H, Berké B, Bégaud B, et al. Immunomodulatory and antitumour effects of abnormal Savda Munziq on S180 tumour-bearing mice. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:157. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]