ABSTRACT

Chlamydia trachomatis infection is the most prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection and can cause significant reproductive morbidity in women. There is insufficient knowledge of C. trachomatis-specific immune responses in humans, which could be important in guiding vaccine development efforts. In contrast, murine models have clearly demonstrated the essential role of T helper type 1 (Th1) cells, especially interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-producing CD4+ T cells, in protective immunity to chlamydia. To determine the frequency and magnitude of Th1 cytokine responses elicited to C. trachomatis infection in humans, we stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 90 chlamydia-infected women with C. trachomatis elementary bodies, Pgp3, and major outer membrane protein and measured IFN-γ-, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-, and interleukin-2 (IL-2)-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses using intracellular cytokine staining. The majority of chlamydia-infected women elicited CD4+ TNF-α responses, with frequency and magnitude varying significantly depending on the C. trachomatis antigen used. CD4+ IFN-γ and IL-2 responses occurred infrequently, as did production of any of the three cytokines by CD8+ T cells. About one-third of TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells coproduced IFN-γ or IL-2. In summary, the predominant Th1 cytokine response elicited to C. trachomatis infection in women was a CD4+ TNF-α response, not CD4+ IFN-γ, and a subset of the CD4+ TNF-α-positive cells produced a second Th1 cytokine.

KEYWORDS: Chlamydia trachomatis, Th1 responses, tumor necrosis factor

INTRODUCTION

Chlamydia trachomatis, an obligate intracellular bacterium, causes mucosal infection (chlamydia) of the genital, anorectal, and oropharyngeal surfaces in humans. Chlamydia is the most prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide (1), and genital chlamydia is associated with significant reproductive morbidity, including tubal factor infertility. Despite over 2 decades of national screening efforts in the United States, the prevalence of chlamydia continues to rise (2). Availability of a chlamydia vaccine could improve chlamydia prevention efforts (3, 4), but vaccine development efforts have been hindered in part by insufficient knowledge of the immune responses to C. trachomatis infection in humans that contribute to protective immunity (5).

Because of the ethical concerns about performing Chlamydia challenge or natural history studies in humans, animal models have played a critical role in identifying the mechanisms of protective immunity to chlamydia (6). In murine models of genital chlamydia, protective immunity is largely mediated through CD4+ T helper type 1 (Th1) cell responses, with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) playing an essential role (7). Another Th1 cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), has also been implicated in protective immunity to chlamydia in murine studies (8–10). TNF-α is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine released from monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes that stimulates a cascade of other cytokines (11). In the murine chlamydia model, the influence of TNF-α on chlamydia clearance appears to be specific to the mucosal site infected. For example, in the mouse pneumonitis model (which uses Chlamydia muridarum), TNF-α deletion significantly accelerates mortality and increases organism burden in the lung (8, 9), suggesting a protective role for TNF-α. However, TNF-α depletion seems to have no effect on C. muridarum clearance from the genital tract (12–14), although its expression in the genital tract increases within days of chlamydia infection (12, 15), suggesting TNF-α alone is not sufficient for chlamydia clearance. Interestingly, several studies demonstrate TNF-α may exert its effects in synergy with other cytokines (16) or interleukins (ILs) (17). One murine study demonstrated that CD4+ T cells producing both IFN-γ and TNF-α correlated with protection against chlamydia challenge (16). While the role of TNF-α in mediating protective immunity remains unclear, murine studies have reported this proinflammatory cytokine may contribute to upper genital tract pathology (13).

Translating immune mechanisms of chlamydia protection from animal studies to humans is difficult, as mechanisms can differ by animal model (7, 18). For example, mice deficient in CD8+ T cells still resolve primary infection (7, 19), yet a nonhuman primate model demonstrated a key role for CD8+ T cells in mediating protection against chlamydia (20). The dominant mucosal mononuclear cell type response to chlamydia also differs by species, with CD4+ T cells being more numerous in the genital tract in mice (21) and CD8+ T cells in the nonhuman primate trachoma model (22). Additionally, differences in Chlamydia species tested, time to infection clearance, estrous cycle duration, and variable susceptibility to upper genital tract infection make correlation to humans difficult (7, 18). In humans, evidence for protective immunity to chlamydia is mainly based on epidemiological studies, which have shown that a history of prior chlamydia, spontaneous resolution of chlamydia, and persons with a high likelihood of repeated chlamydia exposures (e.g., commercial sex workers) are associated with a lower reinfection risk (23–25). Although immune mechanisms that mediate protection against C. trachomatis in humans remain to be fully elucidated, sparse evidence from two prospective human studies that measured C. trachomatis-specific IFN-γ production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay revealed IFN-γ was associated with protective immunity (26, 27).

To advance our understanding of C. trachomatis-specific immune mechanisms that contribute to protective immunity in humans, a more in-depth evaluation of the C. trachomatis-specific T-cell effector responses and T-cell phenotypes is needed. To address this knowledge gap, we have established a cohort of chlamydia-infected women from which we have characterized clinical manifestations and are conducting immunological experiments to help unravel the key C. trachomatis-specific immune mechanisms and their contribution to protective immunity. Here, we present findings from our initial investigation of the C. trachomatis-specific Th1 cytokine responses (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2) in chlamydia-infected women prior to treatment using intracellular cytokine staining.

RESULTS

Ninety women with chlamydia infection at the time of enrollment were investigated in this study (Table 1). The median age was 21 years (range, 16 to 32 years), 97% were African American, and 1% were Hispanic. Fifty-four percent of women were asymptomatic, and 40% were diagnosed with coinfections bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, or vaginal candidiasis. Fifty-seven percent of the women had a history of chlamydia, based on self-report and/or documentation of prior positive chlamydia test results.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the subjects in this study (n = 90)

| Characteristic | Value for characteristic |

|---|---|

| Median age, yr (range) | 21 (16–32) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 87 (97) |

| White | 3 (3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 89 (99) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1) |

| Use of hormonal contraception, n (%) | 41 (46) |

| Median no. (range) of prior sex partners within last 3 moa | 1 (1–5) |

| Prior chlamydia, n (%)b | 51 (57) |

| Asymptomatic, n (%) | 49 (54) |

| Cervicitis, n (%)b | 17 (19) |

| No. (%) with coinfection | |

| HIV | 0 |

| Gonorrhea | 0 |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 26 (29) |

| Trichomoniasis | 3 (3) |

| Candidiasis | 11 (12) |

n = 88.

n = 89.

Of the three Th1 cytokines tested, the predominant CD4+ cytokine elicited by stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from chlamydia-infected women was TNF-α, not IFN-γ.

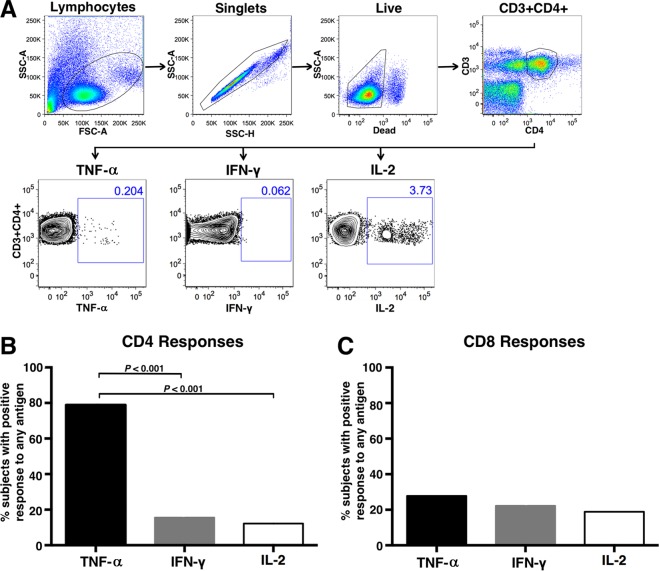

Figure 1A illustrates the gating scheme utilized for the analyses of CD4+ T cells from a representative chlamydia-infected subject, showing Pgp3-stimulated flow cytometry plots. CD8+ T cells were gated similarly. A CD4+ TNF-α response comprised the majority of C. trachomatis-specific CD4+ Th1 cytokine responses to any antigen, with 79% of women mounting a positive CD4+ TNF-α response to any of the 3 antigens, compared to 16% and 12% of women having a CD4+ IFN-γ or IL-2 response, respectively (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). There was no difference in the proportions of women with a positive CD4+ IFN-γ versus IL-2 response. CD8+ T-cell IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 responses were infrequent, with 19 to 28% of subjects' CD8+ T cells eliciting a positive cytokine response for any cytokine to any antigen (Fig. 1C). There was no difference in the proportions of women with a positive CD8+ IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-2 response.

FIG 1.

Intracellular cytokine staining of PBMCs from chlamydia-infected women that were stimulated with C. trachomatis antigens. PBMCs from 90 chlamydia-infected women were stimulated with C. trachomatis MOMP peptides, Pgp3, and EB, and production of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 was measured by intracellular cytokine staining. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the intracellular cytokine staining gating strategy for CD4+ T cells producing TNF-α, IFN-γ, or IL-2. Numbers indicate the percentage of gated cells. CD8+ T cells were gated similarly. Panels B and C show the proportions of women with a positive CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell cytokine response against any of the 3 antigens. A positive cytokine response was defined as >0.05% and twice the background (media + costimulatory antibodies). Significance was evaluated by McNemar's chi-square test.

We further investigated whether a positive response for any of the CD4+ Th1 cytokines was associated with demographic or clinical characteristics of subjects, especially age and history of prior chlamydia, as both have been found to be associated with a reduced risk of reinfection (23, 28). There were no significant associations found between CD4+ Th1 cytokine responses and age, symptom status, history of chlamydia, number of sexual partners, hormonal contraception, cervicitis, or coinfections (data not shown).

The proportion of women with a positive cytokine response varied with the C. trachomatis antigen used for stimulation.

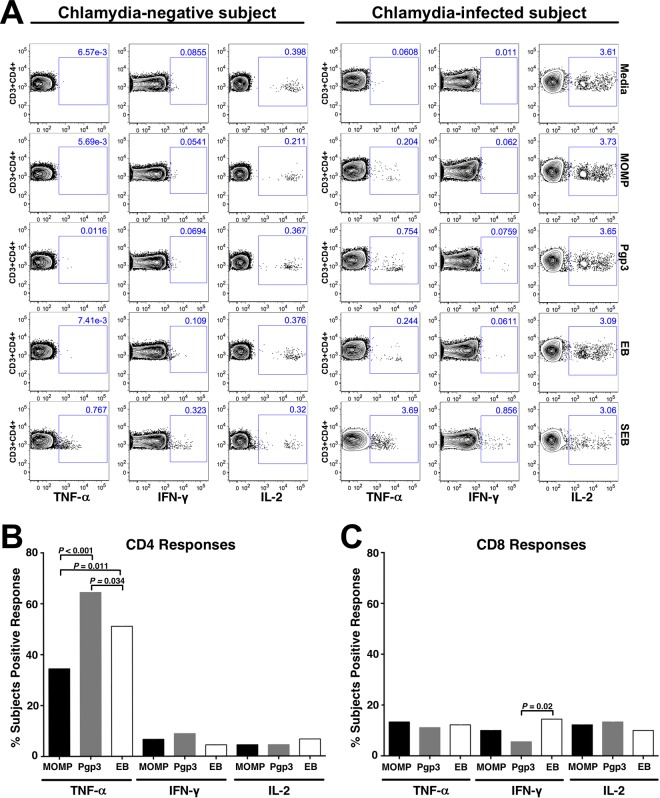

Stratifying the intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) responses by C. trachomatis antigens used for stimulating PBMCs, we assessed whether there was a difference in the proportions of women with a positive cytokine response elicited by different C. trachomatis antigens. Figure 2A shows representative flow cytometry plots for a chlamydia-infected subject and a chlamydia-negative control subject. As shown in Fig. 2B, all three antigens generated predominantly CD4+ TNF-α qualitative responses, but these responses were most often generated with Pgp3 stimulation compared with stimulation with major outer membrane protein (MOMP) (64% versus 34%; P < 0.001) or elementary bodies (EB) (64% versus 51%; P = 0.034). The proportion of women with a positive CD4+ TNF-α response to EB was significantly higher than that to MOMP (51% versus 34%; P = 0.011). There was no significant difference in the proportions of women with a positive CD4+ IFN-γ or IL-2 response between the antigens. The proportion of women with positive CD8+ IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-2 responses across different antigens was lower, with a response occurring in 6 to 15% of women (Fig. 2C). The proportion of women with a positive CD8+ IFN-γ response when stimulated with Pgp3 was significantly lower than that for stimulation with EB (6% versus 14%; P = 0.02); otherwise there was no significant difference in the proportion of women with positive CD8+ cytokine responses between the antigens.

FIG 2.

Percentage of chlamydia-infected women with a positive Th1 cytokine response based on the C. trachomatis antigen used for stimulation of PBMCs. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots from intracellular cytokine staining of CD4+ T cells from a chlamydia-negative subject and chlamydia-infected subject. (B and C) Percentage of women with a positive cytokine response to chlamydia antigens in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. A positive cytokine response was defined as >0.05% and twice the background (media + costimulatory antibodies). Significance was determined using McNemar's chi-square test.

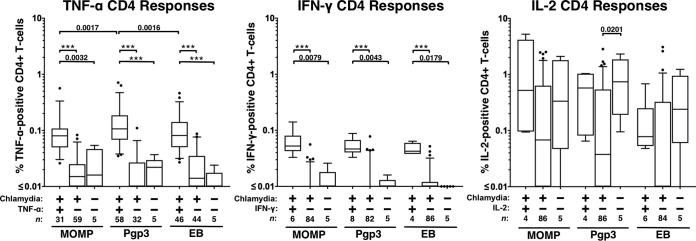

In subjects with a positive Th1 cytokine response, a higher magnitude of TNF-α- and IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells was seen in response to all antigens, with Pgp3 eliciting the highest magnitude of TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells.

Although we expected an increase in the number of cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in subjects with positive cytokine responses to the various antigens compared to cytokine-negative chlamydia-infected women (based on our qualitative analysis cutoff described in Materials and Methods), we wanted to compare the magnitudes of those responses. To evaluate the differences in the magnitudes (measured by percentage of cytokine-positive cells) of the responses between these two groups of women and chlamydia-negative controls (all of whom had a negative response for all Th1 cytokines we tested), we stratified the data into chlamydia-infected cytokine-positive, chlamydia-infected cytokine-negative, and chlamydia-negative control groups. Given the low proportion of women with positive CD8+ cytokine responses, we focused our quantification analyses of cytokine-producing cells on CD4+ T cells. As shown in Fig. 3, comparison of the magnitudes of the cytokine-positive CD4+ responses between antigens showed that Pgp3 elicited a 40% higher CD4+ TNF-α response (median TNF-α-producing cells, 0.11%) than MOMP or EB (0.08% for both; P = 0.0017 and P = 0.0016, respectively). IFN-γ or IL-2 CD4+ cytokine-positive responses were not significantly different between antigens.

FIG 3.

Magnitude of cytokine responses from CD4+ T cells stimulated with C. trachomatis antigens in chlamydia-infected women with a positive or negative cytokine response (qualitative) and in chlamydia-negative control women. Responses were measured by intracellular cytokine staining. A positive cytokine response was defined as >0.05% and twice the background (media + costimulatory antibodies). The magnitude of the cytokine response is shown as a percentage of total CD4+ T cells after subtracting the background response, stratified by the C. trachomatis antigen used. The box denotes the interquartile range, and the whiskers denote the 5th and 95th percentiles. Dots denote outliers. The median is shown as the horizontal line in the box. n denotes the number of subjects. Significance was evaluated by Wilcoxon's signed-rank or rank sum tests. The asterisks denote P < 0.001. The y axis is in log10.

Comparing the magnitudes of the cytokine responses in cytokine-positive chlamydia-infected women to those in either cytokine-negative chlamydia-infected women or chlamydia-negative-control women for each antigen, we found a significant increase in the magnitudes of TNF-α- and IFN-γ-positive CD4+ T-cell responses for the cytokine-positive chlamydia-infected women compared to the other groups for each antigen, but there was no difference in the magnitudes of the IL-2 responses. The median TNF-α-positive CD4+ T-cell responses ranged from 0.080 to 0.11% in cytokine-positive chlamydia-infected women versus 0.010 to 0.015% in cytokine-negative chlamydia-infected women. The median IFN-γ-positive CD4+ cell response ranged from 0.043 to 0.053% in cytokine-positive chlamydia-infected women versus 0.000 to 0.004% in cytokine-negative chlamydia-infected women. There was no difference in the magnitudes of the cytokine responses between cytokine-negative chlamydia-infected women and negative-control women for any of the cytokines, with the exception of Pgp3-stimulated IL-2 responses, which were higher in the control group than those in the chlamydia-infected IL-2-negative group (P = 0.02). Taken together, these data suggest that responses to chlamydia antigens are chlamydia specific and demonstrate the immunogenicity of Pgp3 in generating TNF-α-positive CD4+ T-cell responses.

In CD4+ TNF-α-positive subjects, the frequency of positive responses differed by antigen.

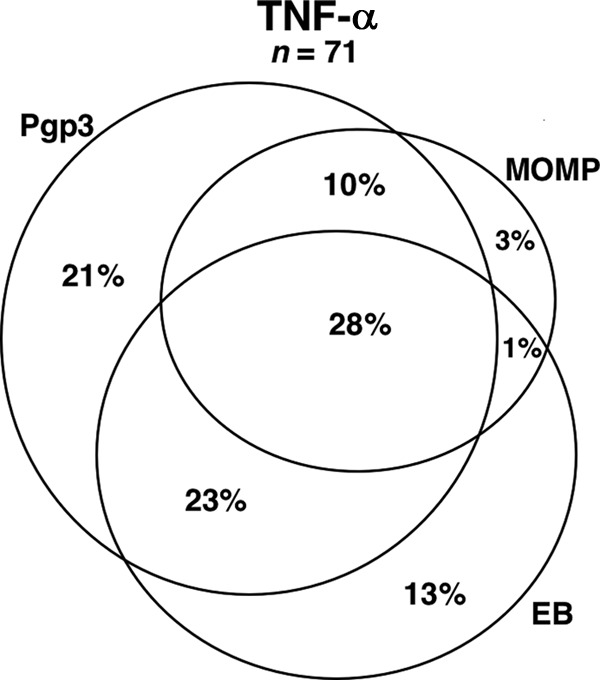

In subjects who had a positive CD4+ TNF-α response, we evaluated the frequency of interantigenic TNF-α-positive responses across each C. trachomatis antigen to determine if the tested antigens generated isolated responses (i.e., cytokine responses only to that antigen). We had initially hypothesized that EB, being a whole C. trachomatis organism, would elicit the greatest cross-antigenic responses due to a more diverse antigen presentation than either Pgp3 or MOMP. Including only women with a positive CD4+ TNF-α response to any antigen (n = 71), we saw significant interantigenic variability, as expected, with 28% of women mounting TNF-α-positive responses to all three antigens, 21% to Pgp3 only, 13% to EB only, and 3% to MOMP only (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Venn diagram demonstrating the overlap of CD4+ TNF-α responses across C. trachomatis antigens used for PBMC stimulation. Subjects with a positive CD4+ TNF-α response to any antigen were identified (n = 71), and the concordance of positive responses across the antigens MOMP, Pgp3, and EB was evaluated. The percentages indicate the proportion of total positive CD4+ TNF-α responses elicited by the antigen(s).

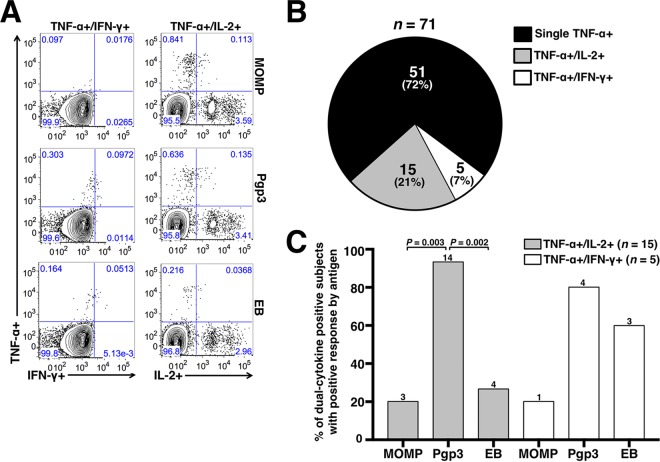

A subset of TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells demonstrated dual-cytokine responses.

Using dual gating, we determined the proportion of TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells that were dual positive for either IL-2 or IFN-γ. Representative dual-gated flow cytometry plots are shown in Fig. 5A. As shown in Fig. 5B, dual-cytokine-positive CD4+ populations were identified in 28% of subjects with positive TNF-α responses, with TNF-α/IL-2 dual-positive responses being more frequently identified than TNF-α/IFN-γ dual-positive responses (21% versus 7%, respectively). Corresponding to the immunodominance observed earlier with Pgp3 eliciting TNF-α responses, Pgp3 elicited a significantly higher frequency of TNF-α/IL-2 dual-positive responses than MOMP (93% versus 20%, respectively; P = 0.003) and EB (93% versus 27%, respectively; P = 0.002) (Fig. 5C). No significant difference by antigen was identified for TNF-α/IFN-γ responses.

FIG 5.

Dual-cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells from chlamydia-infected women expressing TNF-α and either IL-2 or IFN-γ. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots from chlamydia-infected women with dual-positive CD4+ TNF-α and either IFN-γ or IL-2 responses. (B) Pie chart showing proportion of positive CD4+ TNF-α responses that produced TNF-α alone or produced both TNF-α and IL-2 or TNF-α and IFN-γ responses. (C) Percentage of total dual-positive subjects with a dual-positive cytokine response by antigen. n = 15 for a positive CD4+ TNF-α+/IL-2+ response to any of the 3 antigens and n = 5 for a positive CD4+ TNF-α+/IFN-γ+ response to any of the 3 antigens. A positive cytokine response was defined as >0.05% and twice the background (media + costimulatory antibodies). The number of positive responses by antigen is indicated above each bar. Significance was determined using McNemar's chi-square test.

DISCUSSION

With murine chlamydia models convincingly demonstrating the importance of Th1 CD4+ IFN-γ in chlamydia infection clearance (7) and some animal studies demonstrating a potential protective role for TNF-α (8, 29), our study sought to increase our understanding of the frequency and magnitude of C. trachomatis-specific Th1-associated cytokine responses in humans. Using intracellular cytokine staining, we analyzed C. trachomatis-specific TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 cytokine production from both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from chlamydia-infected women before treatment. We report for the first time that the predominant Th1-associated cytokine response in women with chlamydia was a CD4+ TNF-α response, not IFN-γ, with PBMCs from approximately 80% of women eliciting a CD4+ TNF-α response to at least one of the three C. trachomatis antigens we tested. Other CD4+ Th1 cytokine responses, IFN-γ and IL-2, were present, but at much lower frequencies. Also TNF-α-positive responses had a higher magnitude than IFN-γ-positive responses, by almost 2-fold.

The overall frequencies of CD8+ T-cell TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 responses were low, occurring in <30% of infected women. Although one might anticipate low CD8+ responses with the use of a recombinant protein and EB, we also observed weak CD8+ responses with the use of five 17- to 20-mer MOMP peptides, which have been shown to contain strong and functional CD8+ epitopes (30, 31). Furthermore, we did not see any differences in the responses between peptide and protein antigens with longer incubation times before Golgi transport inhibition, which allowed additional time for antigen processing (data not shown). Therefore, we feel confident that our observed low CD8+ responses are accurate, although we cannot exclude the possibility that epitopes not present in our MOMP peptides may contribute to CD8+ responses.

TNF-α is an effector cytokine with known antichlamydial activity. In vitro, recombinant TNF-α alone inhibits C. trachomatis in cell culture (32). C. trachomatis growth inhibition by TNF-α has been shown to be synergistic with IFN-γ, with a 100-fold increase in TNF-α potency (32). Inhibition by TNF-α likely occurs by enhancing mechanisms of IFN-γ-dependent tryptophan depletion, as inhibition can be reversed by tryptophan supplementation in vitro (33). In animal models, the contribution of TNF-α to Chlamydia clearance appears tissue and/or species specific. For example, in the genital tract, studies with mice and guinea pigs show increased TNF-α production during chlamydial infection (15), but the absence of TNF-α does not appear to influence chlamydia clearance (13, 14). However, in the mouse pneumonitis model, TNF-α inhibition increased susceptibility to C. muridarum and increased mortality (8). An in vivo study comparing rates of C. trachomatis and C. muridarum infection of different mouse strains demonstrated that TNF-α-deficient mice had delayed chlamydia clearance, which differed by Chlamydia species (29). This may explain the variation in the influence of TNF-α on Chlamydia growth inhibition and highlights the importance of human studies for understanding mechanisms of chlamydia clearance.

Our finding that TNF-α is the predominant cytokine elicited to the intracellular pathogen C. trachomatis suggests it may be an important component of the systemic effector immune response and is consistent with other studies showing it contributes to the immune response to C. trachomatis. For example, in individuals with trachoma, sequence variation associated with the TNF locus has been associated with increased risk of trachomatous scarring and trichiasis and elevated TNF responses induced by EB (34). The presence of the TNF-α-308A allele has been associated with an increased risk of scarring trachoma (35) and development of severe adhesions in tubal factor infertility caused by C. trachomatis (36). These studies suggest that although TNF-α is an effector cytokine that may contribute to protective immune responses, excess levels of this proinflammatory cytokine can lead to immunopathology after infection (12, 37). Other evidence supporting the importance of TNF-α in immune control of intracellular organisms includes studies demonstrating that TNF-α-inhibitory monoclonal antibodies are strongly associated with an increased susceptibility to infection with the intracellular pathogens Histoplasma and Listeria and reactivation of latent tuberculosis (38). Whether TNF-α is associated with a reduced risk for C. trachomatis reinfection remains unknown, and we are conducting studies that will address this important question.

Our finding that positive Th1 cytokine responses, especially IFN-γ, are not generated in all chlamydia-infected women is consistent with other studies. Two previous human studies evaluated the frequency of positive IFN-γ responses with PBMC stimulation with C. trachomatis antigens, measured by either ELISpot assay or ELISA, but did not evaluate the frequency of other Th1 cytokine responses, including TNF-α (26, 27). In a cohort of commercial sex workers at risk for C. trachomatis infection, Cohen et al. reported positive IFN-γ responses to EB occurred in 40% (26). In a cohort of female adolescents with current or prior C. trachomatis infection, Barral et al. reported positive IFN-γ responses to EB and MOMP occurred in 62% and 38% of adolescents, respectively (27). In our study, we used ICS rather than ELISpot assay or ELISA to characterize cytokines responses, which allowed us to determine IFN-γ responses produced specifically by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. In our cohort of chlamydia-infected women, a positive CD4+ IFN-γ response to any of the 3 antigens occurred in 16% of subjects and a positive CD8+ IFN-γ response in 22% of subjects. Our lower frequency of positive IFN-γ responses compared with those of the studies described above could, in part, reflect differences in assay cutoff for positivity (with all of the studies using different assays) or the fact that we measured IFN-γ produced specifically by CD4+ and CD8+ cells, whereas the above studies likely measured IFN-γ production from all CD3+ T cells with an unknown contribution from other mononuclear cells (e.g., NK cells, monocytes, etc.); it is worth noting that the study by Barral et al. used partially depleted CD8+ cells to limit detection of IFN-γ from that cell source (27), although other mononuclear cells remained present.

Murine studies have revealed that TNF-α can act in synergy with other cytokines, including IL-22 (17) and IFN-γ (16), to modulate the immune response, and the presence of dual-positive TNF-α/IFN-γ CD4+ T-cell responses in mice correlates with protection against chlamydia challenge (16). In our study, we found that almost one-third of TNF-α-positive CD4+ T cells were able to produce two cytokines, with the majority coproducing IL-2 rather than IFN-γ. IL-2, a prosurvival cytokine, is known to positively modulate TNF-α production (39). IL-2 also has an important role in lymphocyte proliferation and arming effector T cells, as well as maintaining effector T cells in the circulation (40). Goon et al. reported a higher frequency of TNF-α/IL-2 dual-cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in patients with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-associated pathology than that in asymptomatic carriers with similar viral load (41). Their observation raises an interesting question about the role of TNF-α/IL-2 dual-cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells in C. trachomatis infection; it would be important to determine whether these dual-cytokine-producing CD4+ T cells contribute to immune protection or pathology.

Our study used a panel of multiple C. trachomatis antigens to provide a more comprehensive characterization of C. trachomatis-specific T-cell responses. We found that Pgp3 most often elicited a positive CD4+ TNF-α-positive response compared with the other antigens and also more often elicited dual-positive CD4+ cytokine responses. To our knowledge, Pgp3 has never been investigated in prior studies of C. trachomatis-specific cytokine cellular immune responses in humans, although it has been demonstrated in a murine model that Pgp3 deficiency significantly attenuates infectivity and pathogenicity of C. trachomatis (42). In our study, both single- and dual-positive TNF-α-producing CD4+ T-cell responses to Pgp3 were higher in frequency and magnitude than responses to MOMP or EB, the latter of which contain, as part of their surface, the chlamydial outer membrane complex comprised of over 300 different proteins (43). Although it remains unclear why EB did not elicit cytokine responses as frequently as Pgp3, it could indicate that the key EB antigenic T-cell epitopes are relatively diluted compared to a single protein like Pgp3, which thereby may blunt the magnitude of the immune response. Although an insufficient EB concentration is another possibility, we think this is unlikely as we used a 4-fold-higher concentration of EB in our ICS assays than Barral et al. (27), and we found that EB generally elicited more frequent CD4+ TNF-α responses than MOMP and comparable IFN-γ responses (Fig. 2B and C). Although the difference in percentage of positive cells elicited by Pgp3 stimulation versus the other antigens may appear insignificant (0.11% versus 0.08%), that represents an approximate 40% increase in circulating TNF-α-positive CD4+ T cells, and a magnitude of 0.1% is consistent with CD4+ T-cell responses reported by others in postvaccinated subjects vaccinated with hepatitis B (44), influenza (45), and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) (46) vaccines. Additionally, the observation that Pgp3 generated more dual-positive responses than MOMP or EB may be an important observation for Pgp3 vaccine candidacy since TNF-α/IFN-γ dual-positive responses have been shown to be functionally superior and elicit protective responses in murine models (16).

Our study had strengths and limitations. This is the largest study investigating human C. trachomatis-specific T-cell responses using ICS; a previous study by Miguel et al. that used ICS only studied cytokine responses in 14 C. trachomatis-infected women and did not present data on the proportion of women with a positive response (47). Because we included multiple C. trachomatis antigens in our ICS studies, we were able to investigate interantigenic variation of cytokine responses, which revealed significant variability in CD4+ TNF-α responses. Our study is the first to evaluate C. trachomatis-specific cellular immune responses through incorporation of dual gating into our ICS methodology, which allowed us to differentiate single-cytokine-producing cells from dual-cytokine-producing cells. One notable caveat with our findings is that the majority of subjects studied were African American, representative of the race/ethnicity of the clinic population, and therefore these findings may not be generalizable to other populations. In this study, we focused on Th1 cytokine responses, which was the aim of our initial investigation into C. trachomatis-specific immune responses in humans because of animal models demonstrating the importance of Th1 responses (7). In future studies, we will be evaluating a broader group of cytokines, including Th2-associated cytokines, and will evaluate immune responses at follow-up visits to determine longevity of C. trachomatis-specific immune responses and association of cytokine responses (single and dual functional) with chlamydia reinfection. Ultimately, we hope to identify immune correlates of protection to C. trachomatis infection in humans.

In summary, the predominate Th1-associated cytokine response in women with uncomplicated chlamydia was a CD4+ TNF-α response, and CD4+ T cells producing both TNF-α and IL-2 were not uncommon. The frequency of CD4+ TNF-α responses was influenced by the antigen used for stimulation of PBMCs, with Pgp3 most often eliciting CD4+ TNF-α single- and dual-positive responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and procedures.

The study population was comprised of females ≥16 years of age who presented to the Jefferson County Department of Health (JCDH) STD Clinic in Birmingham, AL, USA, for treatment based on a recent positive C. trachomatis screening nucleic acid amplification test (Aptima Combo 2 [AC2]; Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA). Patients did not receive empirical chlamydia therapy at the time of screening because they had no cervicitis findings and no other chlamydia treatment indications. Patients interested in the study provided written consent and were enrolled. Women who were pregnant, had a prior hysterectomy, were coinfected with HIV, syphilis, or gonorrhea (tested at screening), were immunosuppressed, or had received antibiotics with antichlamydial activity in the prior 30 days were excluded.

At enrollment, participants were interviewed and demographic, clinical, and behavioral data were collected. A pelvic examination was performed in which a vaginal swab specimen was collected for wet mount microscopy and an endocervical swab specimen for chlamydia and gonorrhea testing by the AC2 per the manufacturer's instructions. Blood was collected for isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). All participants received directly observed therapy with 1 g azithromycin and were advised to refer all sexual partners for treatment, if not already treated. PBMCs from five healthy, low-risk C. trachomatis-seronegative women (tested with a C. trachomatis elementary body-based ELISA [48]) without a history of chlamydia were used as negative controls. The study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board and JCDH.

PBMC isolation.

At the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences Specimen Processing and Analytical Nexus, PBMCs were isolated from blood by centrifugation through lymphocyte separation medium (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA). Upon isolation, cells were counted and examined for viability. PBMCs were frozen in 1-ml aliquots in 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until used for immunological studies.

ICS.

PBMCs were stimulated with C. trachomatis antigens and analyzed for cytokines as previously reported, with modifications (49). Briefly, 2.5 × 105 cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 in RPMI-10 medium (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% human AB serum, penicillin-streptomycin [50 U/ml], HEPES [25 mM], and l-glutamine [2 mM]) in the presence of costimulatory antibodies CD28 and CD49d (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and antigen, followed by a 5-h incubation in the presence of brefeldin A and monensin (both from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). The antigens used were recombinant C. trachomatis Pgp3 (5 μg/ml) (Biorbyt, San Francisco, CA), pooled major outer membrane protein (MOMP) peptides (5 μg/ml) (VS1 75-92, VS2 132-151, VS2 145-163, VS4 300-318, and VS4 308-324; UAB Peptide Core, Birmingham, AL), formalin-fixed C. trachomatis elementary bodies (EB [4 μg/ml]) representing pooled serotypes D, F, and J (obtained from Richard Morrison from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR), and Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB [10 μg/ml]) (Toxin Technologies, Sarasota, FL) as the positive control. RPMI-10 supplemented with anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d antibodies, but without antigen, was used to determine background T-cell responses. Cells were subsequently labeled with LIVE/DEAD fluorescent-reactive dye (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR), stained with surface antibodies CD3-Pacific Blue (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), CD4-Qdot 655, and CD8-Qdot 605 (both from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), fixed and permeabilized (Cytofix/Cytoperm; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), and stained with antibodies for intracellular cytokines IFN-γ–Alexa 700, TNF-α-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7, and IL-2–PE (all from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Approximately 100,000 events were acquired on a LSRII (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Diego, CA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software v9.8.5 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). All responses are reported after subtracting the background responses (media + costimulatory antibodies).

Statistical analysis.

Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. We evaluated quantitative and qualitative differences in cytokine responses—the latter to allow comparison with prior studies (26, 27). Cytokine responses of >0.05% and twice the background response (media + costimulatory antibodies) were considered positive for our qualitative analyses. Differences in frequencies of each CD4+ cytokine response and each CD8+ cytokine response were evaluated by McNemar's chi-square test. Differences in frequency of a specific cytokine response based on C. trachomatis antigen used for the stimulation were also evaluated by McNemar's chi-square test. Differences in the magnitudes of CD4+ TNF-α responses (enumeration of cytokine-producing cells) by C. trachomatis antigen were evaluated with the Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Differences in the magnitudes of cytokine-positive responses between chlamydia-infected cytokine-positive, chlamydia-infected cytokine-negative, and negative-control groups were evaluated with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Associations of subjects' demographic or clinical characteristics with specific cytokine responses were evaluated with the Pearson's chi-square, Fisher's exact, or Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate. Differences were considered significant at a P value of <0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hanne Harbison and Cynthia Poore for assistance in collection of specimens and clinical data for the study. We thank Richard Morrison for providing the C. trachomatis elementary bodies used in our immunological assays.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (award R01AI093692 to W.M.G.) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award UL1TR001417). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. WHO guidelines for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray RT, Beagley KW, Timms P, Wilson DP. 2009. Modeling the impact of potential vaccines on epidemics of sexually transmitted Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect Dis 199:1680–1688. doi: 10.1086/598983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de la Maza MA, de la Maza LM. 1995. A new computer model for estimating the impact of vaccination protocols and its application to the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Vaccine 13:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)80022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunham RC, Rappuoli R. 2013. Chlamydia trachomatis control requires a vaccine. Vaccine 31:1892–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Clercq E, Kalmar I, Vanrompay D. 2013. Animal models for studying female genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 81:3060–3067. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00357-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rank RG, Whittum Hudson JA. 2010. Protective immunity to chlamydial genital infection: evidence from animal studies. J Infect Dis 201(Suppl 2):S168–S177. doi: 10.1086/652399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DM, Magee DM, Bonewald LF, Smith JG, Bleicker CA, Byrne GI, Schachter J. 1990. A role in vivo for tumor necrosis factor alpha in host defense against Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 58:1572–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DM, Grubbs BG, Pack E, Kelly K, Rank RG. 1997. Humoral and cellular immunity in secondary infection due to murine Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 65:2876–2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darville T, Andrews CW, Laffoon KK, Shymasani W, Kishen LR, Rank RG. 1997. Mouse strain-dependent variation in the course and outcome of chlamydial genital tract infection is associated with differences in host response. Infect Immun 65:3065–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiers W. 1991. Tumor necrosis factor. Characterization at the molecular, cellular and in vivo level. FEBS Lett 285:199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murthy AK, Li W, Chaganty BKR, Kamalakaran S, Guentzel MN, Seshu J, Forsthuber TG, Zhong G, Arulanandam BP. 2011. Tumor necrosis factor alpha production from CD8+ T cells mediates oviduct pathological sequelae following primary genital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun 79:2928–2935. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamalakaran S, Chaganty BKR, Gupta R, Guentzel MN, Chambers JP, Murthy AK, Arulanandam BP. 2013. Vaginal chlamydial clearance following primary or secondary infection in mice occurs independently of TNF-α. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darville T, Andrews CW, Rank RG. 2000. Does inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha affect chlamydial genital tract infection in mice and guinea pigs? Infect Immun 68:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5299-5305.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darville T, Laffoon KK, Kishen LR, Rank RG. 1995. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activity in genital tract secretions of guinea pigs infected with chlamydiae. Infect Immun 63:4675–4681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, Karunakaran KP, Kelly I, Shen C, Jiang X, Foster LJ, Brunham RC. 2011. Immunization with live and dead Chlamydia muridarum induces different levels of protective immunity in a murine genital tract model: correlation with MHC class II peptide presentation and multifunctional Th1 cells. J Immunol 186:3615–3621. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao X, Zhu D, Ye J, Li X, Wang Z, Zhang L, Xu W. 2015. The potential protective role of the combination of IL-22 and TNF-α against genital tract Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Cytokine 73:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyairi I, Ramsey KH, Patton DL. 2010. Duration of untreated chlamydial genital infection and factors associated with clearance: review of animal studies. J Infect Dis 201(Suppl 2):S96–S103. doi: 10.1086/652393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrison SG, Su H, Caldwell HD, Morrison RP. 2000. Immunity to murine Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract reinfection involves B cells and CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells. Infect Immun 68:6979–6987. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6979-6987.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olivares-Zavaleta N, Whitmire WM, Kari L, Sturdevant GL, Caldwell HD. 2014. CD8+ T cells define an unexpected role in live-attenuated vaccine protective immunity against Chlamydia trachomatis infection in macaques. J Immunol 192:4648–4654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly KA, Rank RG. 1997. Identification of homing receptors that mediate the recruitment of CD4 T cells to the genital tract following intravaginal infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 65:5198–5208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Voorhis WC, Barrett LK, Sweeney YT, Kuo CC, Patton DL. 1997. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection of Macaca nemestrina fallopian tubes produces a Th1-like cytokine response associated with fibrosis and scarring. Infect Immun 65:2175–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz BP, Batteiger BE, Jones RB. 1987. Effect of prior sexually transmitted disease on the isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis 14:160–164. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunham RC, Kimani J, Bwayo J, Maitha G, Maclean I, Yang C, Shen C, Roman S, Nagelkerke NJ, Cheang M, Plummer FA. 1996. The epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis within a sexually transmitted diseases core group. J Infect Dis 173:950–956. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geisler WM, Lensing SY, Press CG, Hook EW. 2013. Spontaneous resolution of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women and protection from reinfection. J Infect Dis 207:1850–1856. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen CR, Koochesfahani KM, Meier AS, Shen C, Karunakaran K, Ondondo B, Kinyari T, Mugo NR, Nguti R, Brunham RC. 2005. Immunoepidemiologic profile of Chlamydia trachomatis infection: importance of heat-shock protein 60 and interferon-γ. J Infect Dis 192:591–599. doi: 10.1086/432070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barral R, Desai R, Zheng X, Frazer LC, Sucato GS, Haggerty CL, O'Connell CM, Zurenski MA, Darville T. 2014. Frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis-specific T cell interferon-γ and interleukin-17 responses in CD4-enriched peripheral blood mononuclear cells of sexually active adolescent females. J Reprod Immunol 103:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarro C, Jolly A, Nair R, Chen Y. 2002. Risk factors for genital chlamydial infection. Can J Infect Dis 13:195. doi: 10.1155/2002/954837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perry LL, Su H, Feilzer K, Messer R, Hughes S, Whitmire W, Caldwell HD. 1999. Differential sensitivity of distinct Chlamydia trachomatis isolates to IFN-γ-mediated inhibition. J Immunol 162:3541–3548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SK, Angevine M, Demick K, Ortiz L, Rudersdorf R, Watkins D, DeMars R. 1999. Induction of HLA class I-restricted CD8+ CTLs specific for the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis in human genital tract infections. J Immunol 162:6855–6866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SK, Devine L, Angevine M, DeMars R, Kavathas PB. 2000. Direct detection and magnetic isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein-specific CD8+ CTLs with HLA class I tetramers. J Immunol 165:7285–7292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. 1988. Inhibition of Chlamydia trachomatis growth by recombinant tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun 56:2503–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shemer-Avni Y, Wallach D, Sarov I. 1989. Reversion of the antichlamydial effect of tumor necrosis factor by tryptophan and antibodies to beta interferon. Infect Immun 57:3484–3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natividad A, Hanchard N, Holland MJ, Mahdi OSM, Diakite M, Rockett K, Jallow O, Joof HM, Kwiatkowski DP, Mabey DCW, Bailey RL. 2007. Genetic variation at the TNF locus and the risk of severe sequelae of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection in Gambians. Genes Immun 8:288–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conway DJ, Holland MJ, Bailey RL, Campbell AE, Mahdi OS, Jennings R, Mbena E, Mabey DC. 1997. Scarring trachoma is associated with polymorphism in the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) gene promoter and with elevated TNF-alpha levels in tear fluid. Infect Immun 65:1003–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohman H, Tiitinen A, Halttunen M, Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Surcel HM. 2009. Cytokine polymorphisms and severity of tubal damage in women with Chlamydia-associated infertility. J Infect Dis 199:1353–1359. doi: 10.1086/597620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manam S, Thomas JD, Li W, Maladore A, Schripsema JH, Ramsey KH, Murthy AK. 2015. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily member 1b on CD8+ T cells and TNF receptor superfamily member 1a on non-CD8+ T cells contribute significantly to upper genital tract pathology following chlamydial infection. J Infect Dis 211:2014–2022. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rychly DJ, DiPiro JT. 2005. Infections associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Pharmacotherapy 25:1181–1192. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddy J, Chastagner P, Fiette L, Liu X, Thèze J. 2001. IL-2-induced tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-beta expression: further analysis in the IL-2 knockout model, and comparison with TNF-alpha, lymphotoxin-beta, TNFR1 and TNFR2 modulation. Int Immunol 13:135–147. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyman O, Sprent J. 2012. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 12:180–190. doi: 10.1038/nri3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goon PKC, Igakura T, Hanon E, Mosley AJ, Asquith B, Gould KG, Taylor GP, Weber JN, Bangham CRM. 2003. High circulating frequencies of tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-2-secreting human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1)-specific CD4+ T cells in patients with HTLV-1-associated neurological disease. J Virol 77:9716–9722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9716-9722.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramsey KH, Schripsema JH, Smith BJ, Wang Y, Jham BC, O'Hagan KP, Thomson NR, Murthy AK, Skilton RJ, Chu P, Clarke IN. 2014. Plasmid CDS5 influences infectivity and virulence in a mouse model of Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital infection. Infect Immun 82:3341–3349. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01795-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Afrane M, Clemmer DE, Zhong G, Nelson DE. 2010. Identification of Chlamydia trachomatis outer membrane complex proteins by differential proteomics. J Bacteriol 192:2852–2860. doi: 10.1128/JB.01628-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang JJ, Wightman F, Bartholomeusz A, Ayres A, Kent SJ, Sasadeusz J, Lewin SR. 2005. Reduced hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-HBV-coinfected individuals receiving HBV-active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol 79:3038–3051. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3038-3051.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolfi DV, Mansfield KD, Kurupati RK, Kannan S, Doyle SA, Ertl HCJ, Schmader KE, Wherry EJ. 2013. Vaccine-induced boosting of influenza virus-specific CD4 T cells in younger and aged humans. PLoS One 8:e77164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin W-HW, Pan C-H, Adams RJ, Laube BL, Griffin DE. 2014. Vaccine-induced measles virus-specific T cells do not prevent infection or disease but facilitate subsequent clearance of viral RNA. mBio 5:e01047-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01047-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vicetti Miguel RD, Harvey SAK, LaFramboise WA, Reighard SD, Matthews DB, Cherpes TL. 2013. Human female genital tract infection by the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis elicits robust type 2 immunity. PLoS One 8:e58565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geisler WM, Morrison SG, Doemland ML, Iqbal SM, Su J, Mancevski A, Hook EW, Morrison RP. 2012. Immunoglobulin-specific responses to Chlamydia elementary bodies in individuals with and at risk for genital chlamydial infection. J Infect Dis 206:1836–1843. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang S, Bakshi RK, Suneetha PV, Fytili P, Antunes DA, Vieira GF, Jacobs R, Klade CS, Manns MP, Kraft ARM, Wedemeyer H, Schlaphoff V, Cornberg M. 2015. Frequency, private specificity, and cross-reactivity of preexisting hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD8+ T cells in HCV-seronegative individuals: implications for vaccine responses. J Virol 89:8304–8317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00539-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]