Abstract

The present study examines whether individuals with a history of child sexual abuse are at risk of sexual revictimization in marriage and, if so, whether these experiences are associated with increased trauma symptomatology. Two hundred heterosexual newlywed couples were recruited from marriage license records and completed self-report assessments of past sexual victimization and sexual coercion within the marital dyad. Actor-Partner Interdependence Models revealed that, compared to non-victims, women with a history of child sexual abuse (CSA) experienced more acts of sexual coercion by their husbands during the past year. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between CSA and sexual coercion such that, among women who experienced CSA, the relationship between marital revictimization and trauma symptoms was stronger. Findings suggest that, for women but not men, sexual revictimization may occur in the context of a new marriage, and these experiences are associated with increased trauma symptoms. These findings have implications for understanding female survivors’ perceptions of risk, and are particularly concerning given the high degree of personal and legal commitment involved in marriage.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, long-term effects, intimate partner violence, sexual assault

Child sexual abuse is a widespread problem, affecting approximately 20% of women and 8% of men internationally (Pereda, Guilera, Forns, & Gómez-Benito, 2009). One well-established finding is that individuals with a history of early sexual abuse are more likely to experience a sexual assault in adulthood than those without a history of sexual abuse (e.g., Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Messman-Moore & Long, 2003). Although most often studied in women, sexual revictimization has also been demonstrated in men (Coxell, King, Mezey, & Gordon, 1999; Desai, Arias, Thompson, & Basile, 2002; Elliott, Mok, & Briere, 2004; Nelson et al., 2002). The relationships between victims and those who perpetrate against them are varied. Among sexually assaulted women, 16.7% report being assaulted by a stranger, 21.3% by an acquaintance, 6.5% by a relative who is not a spouse, and 61.9% by an intimate partner (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Although intimate partners are most often the perpetrators of adult sexual assaults against women (Black et al., 2011)1, studies of sexual revictimization typically focus on stranger and acquaintance perpetrators. Recent studies have added to this literature, revealing positive associations between a history of child sexual abuse (CSA) and adult sexual victimization by an intimate partner (Chan, 2011; Daigneault, Hébert, & McDuff, 2009; Jaffe, Cranston, & Shadlow, 2012; Messing, La Flair, Cavanaugh, Kanga, & Campbell, 2012; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, & Livingston, 2007).

Despite indications that revictimization occurs at the hands of intimate partners, it remains unclear whether revictimization occurs specifically in the context of marital relationships. However, several unique characteristics of marriage make this an important relational context in which to examine possible revictimization. Unlike other romantic relationships, marriage is a legally sanctioned union between partners who have espoused a lifelong commitment to each other. Yet, the physical proximity that comes with marital cohabitation may not only increase opportunities for revictimization to occur but can also leave victims with an ongoing sense of vulnerability to future abuse. Moreover, marital partners experience a high degree of interdependence, not only emotionally but also structurally, through shared financial arrangements, overlapping social networks, and perhaps joint child rearing (e.g., Kearns & Leonard, 2004). This interdependence may limit victims’ responses to revictimization, including their ability to seek safety by leaving the relationship. Finally, the physical and emotional violations of sexual victimization are antithetical to many attributes of a lasting relationship (e.g., trust, mutual respect, and support between spouses; Bachand & Caron, 2001), potentially jeopardizing the marriage itself. Together, these factors indicate that the marital relationship is an especially challenging context in which sexual revictimization may occur. It appears, however, that no prior work has examined sexual revictimization specifically among married couples.

In the present study, we investigate the occurrence and psychological ramifications of sexual revictimization in a sample of newlywed couples. On one hand, we might predict that sexual revictimization would be rare among newlywed couples. As a whole, this group reports strong marital satisfaction (Lavner, Bradbury, & Karney, 2012). Accordingly, we might reasonably expect high levels of trust and perceived safety in these couples—characteristics that are seemingly incompatible with the perpetration of sexual aggression. On the other hand, there are reasons to suspect that adult victims of CSA are at risk of further victimization at the hands of a spouse. If, as theorized, adult victims of CSA hold misconceptions about the role and meaning of sex, and experience confusion about sexual norms (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985), these beliefs may affect the degree to which one perceives sexually aggressive behavior from partners to be normative. Moreover, some adults with a history of sexual abuse may be motivated to minimize their partners’ use of aggressive behavior because of an overwhelming desire to be in a romantic relationship that is free of fear or vulnerability (Davis & Petretic-Jackson, 2000). There is also evidence from the assortative mating literature that men and women tend to choose long-term romantic partners with whom they identify and perceive as similar to themselves (Buss, 1985; Kalick & Hamilton, 1986; South, 1991) along dimensions such as psychiatric symptomatology (du Fort, Kovess, & Boivin, 1994; Maes et al., 1998), drinking behaviors (Leonard & Das Eiden, 1999), and antisocial tendencies (Han, Weed, & Butcher, 2003). Unfortunately, these characteristics are also common sequelae among women with a history of sexual abuse (e.g., Chen et al., 2010; Maniglio, 2011), as well as characteristics of sexually aggressive men (e.g., Calhoun, Bernat, Clum, & Frame, 1997; Testa, 2002). If adults with a history of CSA enter romantic relationships with partners who mirror themselves along these dimensions, the result may be an increased risk for revictimization in marriage.

Sexual revictimization occurring in the context of marriage would be concerning for many reasons, including the potential for these experiences to compound already existing psychological difficulties among victims. Research consistently shows that revictimization is associated with a host of negative psychological outcomes, beyond that associated with a single victimization experience (see Messman-Moore, Long, & Siegfried, 2000). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder are especially prevalent among those who are revictimized (Arata, 1999; Ullman & Peter-Hagene, 2016; Walsh et al., 2012), with evidence suggesting a cumulative impact of multiple sexual victimizations on trauma symptoms (e.g., Follette, Polusny, Bechtle, & Naugle, 1996). Despite these general findings, and specific indications that sexual assault in marriage may leave victims feeling violated, confused, and betrayed by a loved one (e.g., Mahoney & Williams, 1998), no known studies have examined the potential cumulative psychological effects resulting from sexual revictimization in marriage. Reflecting the larger literature on sexual revictimization, we expect that revictimization by a marital partner will be associated with increased trauma symptoms.

A primary goal of this study is to investigate associations between wives’ and husbands’ sexual abuse histories and both partners’ experience of sexual coercion in the context of new marriage. Prior work examining revictimization at the hands of intimate partners has tended to use individual- rather than couple-level data (e.g., Daigneault et al., 2009; Testa et al., 2007). However, this individual approach does not address the possibility that each partner’s experiences of past CSA and sexual coercion in the relationship may influence the other partner. To address this, we employed Actor-Partner Interdependence Models (APIM; Kashy & Kenny, 1999; Kenny, 1996), which allow for the evaluation of actor effects (i.e., the degree to each partner’s CSA history impacts his/her own victimization in marriage) and partner effects (i.e., the degree to which each partner’s CSA history impacts the other partner’s marital victimization).

Within this dyadic approach, we first hypothesized that, for both wives and husbands, those with a history of CSA would experience greater sexual coercion from a spouse during the first year of marriage. In addition to impacting women’s and men’s own sexual victimization in the relationship (i.e., actor effects), each individual’s sexual abuse history may also have a bearing on their partners’ risk of victimization in the relationship (i.e., partner effects) such that partners with a history of CSA would be more likely to perpetrate against their spouse.

Second, we examined the psychological toll of revictimization by assessing wives’ and husbands’ reports of trauma-related symptoms. We expected that women’s and men’s own experiences of sexual victimization as a child and adult would interact, such that among those who experienced CSA, the relationship between sexual victimization by a spouse and trauma-related symptoms would be stronger (actor effects). The analyses conducted also produce partner effects, permitting us to explore the relationship between an individual’s revictimization and his or her spouse’s trauma symptoms. Given the lack of prior research in this area, no specific hypotheses were made with regard to these effects.

Method

Participants

Participants were 204 heterosexual newlywed couples (N = 408 participants) randomly recruited from publicly available marriage license records. Both spouses were required to be in their first marriage and at least 19 years of age (the legal age of majority in Nebraska) at the time of data collection. Recruitment efforts resulted in a sample of couples that had been married between 11 and 15 months at the time of data collection. A total of four couples were excluded from analyses due to missing data2, leaving a final sample of 200 couples. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 50 (M = 26.56, SD = 4.10). Reflecting the ethnic makeup of the recruitment area, 93.3% of participants identified as European American, 1.5% Hispanic/Latino, 0.8% African American, 0.8% Native American, and 0.8% Asian American; 3.0% did not report their ethnicity. Reports of current household income were as follows: $40,000 or less = 43.87%; $41,000 to 80,000 = 46.08%; and greater than $81,000 = 7.8%; 2.2% did not report on current income.

Measures

Child sexual abuse

The Computer Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI; DiLillo et al., 2010) is a web-based, self-report questionnaire used to assess experiences of child maltreatment retrospectively from adults. For the purposes of the present study, only the CAMI sexual abuse subscale was used. On this subscale, participants respond to a series of behaviorally specific screener questions that assess whether they have experienced various abusive acts prior to age 18 (i.e., fondling, attempted intercourse, intercourse) under circumstances that were any of the following: (a) against their will; (b) involved a close family relative; or (c) involved someone significantly older than themselves (i.e., more than five years older if the victim was 13 or younger; 10 or more years older if the victim was 14–17 years old). Those who respond affirmatively to any screener are identified as victims. The sensitivity and specificity of the CAMI in detecting sexual abuse has been supported in prior research (DiLillo, Fortier et al., 2006), as has participants’ willingness to disclose abuse via the CAMI’s computer administered format (DiLillo, DeGue et al., 2006). The CAMI has solid test-retest reliability and criterion related validity and is free from significant social desirability biases (DiLillo et al., 2010).

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) is a 28-item scale designed to measure five subtypes of child maltreatment (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect, emotional abuse and neglect). For the purposes of the present study, only the CTQ sexual abuse subscale was used. This subscale is comprised of five items tapping various aspects of sexual abuse, which are scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true) in response to the stem “When I was growing up….” Sample items from this subscale include “Someone tried to touch me in a sexual way, or tried to make me touch them” and “Someone tried to make me do sexual things or watch sexual things.” The CTQ can be used to classify individuals as abused or non-abused based on cut scores provided by the authors. The CTQ also provides a continuous score that serves as an index of abuse severity. The developers of the CTQ report strong internal consistency for the sexual abuse subscale across a variety of samples, as well as solid criterion-related validity of the severity scores across samples in the form of expected convergent and discriminant correlations with interview data and therapists’ independent ratings of participants’ abuse history (Bernstein & Fink, 1998).

Although the correspondence between the CAMI and CTQ is high (92% overlap in classification of victim status), each has been found to detect some unique cases of CSA (DiLillo, Fortier, et al., 2006). Thus, to maximize our ability to detect victimization experiences among participants, endorsement of child sexual abuse on either measure resulted in the participant being classified as a victim of CSA.

Sexual victimization in marriage

The seven-item sexual coercion subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to assess sexual coercion victimization of each partner (perpetrated by the other partner) during the past 12 months. Respondents utilized a 7-point Likert scale anchored from 0 (never happened) to 6 (more than 20 times in the past year) to indicate the frequency of sexually coercive behaviors such as “I used threats to make my partner have sex” and “My partner made me have sex without a condom” (Straus et al., 1996). Scores were computed by summing the number of endorsed items, with higher scores indicating more partner aggression. This scoring method gives equal weight to each form of abusive behavior. Both the wife and husband reported on: (a) their own victimization, and (b) their own perpetration (i.e., the other partner’s victimization). To guard against underreporting, the score of the partner who reported a greater frequency of abuse was used in all analyses for both victimization scores (i.e., participants’ reports of their partner’s behavior and partners’ report of their own behavior). Because these scores reflect count data aggregated across partners, coefficient alpha as a measure of internal consistency is not applicable.

Trauma symptoms

The Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI; Briere, 1995) consists of 100 items assessing frequency of trauma-related sequelae over the prior 6 months on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (often). The TSI has ten clinical subscales; however, for efficiency of analysis and interpretation—and consistent with prior work (e.g., Messman-Moore, Brown, & Koelsh, 2005; Resick, Nishith, & Griffin, 2003)—we used three factor analytically derived sum scores (see Briere, 1995). The Trauma Symptom score is a sum of 34 items representing the Intrusive Experiences, Defensive Avoidance, Dissociation, and Impaired Self-Reference subscales (α = .93). Trauma symptoms are therefore reflective of some posttraumatic stress symptoms (intrusions, avoidance, dissociation, as well as trauma-related disturbances in perceptions of the self and self-identity). The Self-Dysfunction Symptom score is a sum of 26 items representing the Sexual Concerns, Dysfunctional Sexual Behavior, and Tension-Reduction Behavior subscales (α = .87). Therefore, self-dysfunction symptoms generally refer to sexual-related problems and conflicts, as well as maladaptive attempts to cope with negative affect. Lastly, the Dysphoria score is a sum of 25 items representing the Anger/Irritability, Depression, and Anxious Arousal subscales (α = .92). Dysphoria therefore represents general distress or dysphoric moods that may arise following traumatic experiences.

Procedure

Participants were recruited in 2004 through a publicly available database of all marriage license applications in Lancaster County, Nebraska. As their one year anniversary approached, couples were randomly selected from this database and mailed a letter inviting them to participate. These efforts resulted in a response rate of 14.7%, which is comparable to other studies using this method (e.g., Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997). The measures used in this study were part of a larger investigation of childhood maltreatment in relation to adult marital functioning. Spouses completed all questionnaires via computer in separate rooms to ensure privacy and prevent discussion of answers. Upon completion of the study, a $75 incentive was paid to each couple. The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Analytic Strategy

We used Actor Partner Interdependence Models (APIM; Kashy & Kenny, 1999; Kenny 1996), which account for the interdependence of dyadic data and allow for the concurrent modeling of actor and partner effects, to examine our hypotheses. In addition to modeling actor and partner effects, APIM allows each predictor to correlate with the other predictors and includes a correlation between the residuals of the two outcomes that represents the nonindependence of the outcomes not explained by the model. Analyses were conducted under maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) using Mplus v. 7 software (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to guard against Type I errors that might arise from skewed response variable data and to appropriately address missing data (e.g., Enders, 2010). First, an APIM with history of CSA as a predictor and sexual coercion as an outcome was estimated. The sexual coercion victimization outcome contained a large number of zeroes (couples reporting no sexual coercion victimization) and its distribution had a positive skew. This outcome was based on count data, or, in other words, was calculated by counting (or adding) the number of endorsed sexual coercion victimization acts. Thus, a general linear model, which assumes a normal distribution of residuals, was not appropriate for this outcome. Instead, we considered generalized linear models appropriate for count data. Because Mplus does not allow the correlation of two count outcomes, we defined a dummy factor to fit a residual correlation between the outcomes. Our final model used a Poisson distribution3, in which the model-predicted mean of the outcome is equal to its residual variance (Agresti, 1996).

We next estimated models for each of the three TSI composites in which CSA, sexual coercion victimization, and the interaction between CSA and sexual victimization were predictors. For CSA, 0 indicated no CSA and 1 indicated a history of CSA. Sexual victimization in marriage was centered at its lowest possible value, such that 0 indicated no sexual victimization. Interaction effects were constructed by multiplying each person’s CSA and sexual coercion variables. The estimated models were saturated and all fit indices were at their ideal values.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 38 (19.0%) women and 13 (6.5%) men reported a history of CSA. In four couples (2.0%), both partners reported a history of CSA. One hundred (50.0%) women and 82 (42.0%) men experienced at least one act of sexual coercion by their spouse in the previous year (see Table 1). In 69 couples (34.5%), both partners were reported to be sexually coercive and experience coercion. Intercorrelations among study variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

| Variables | Mean (SD) or n (%) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||||||||

| 1. CSA | 13 | (6.5%) | -- | |||||||||

| 2. Sexual coercion victimization | 0.58 | (0.83) | 0 – 5 | −.04 | -- | |||||||

| 3. TSI trauma | 51.25 | (12.35) | 34 – 105 | .23** | .28** | -- | ||||||

| 4. TSI self-dysfunction | 33.09 | (6.80) | 26 – 65 | .22** | .11 | .46** | -- | |||||

| 5. TSI dysphoria | 39.96 | (9.40) | 26 – 70 | .19** | .16* | .67** | .45** | -- | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Women | ||||||||||||

| 6. CSA | 38 | (19%) | .08 | .17* | .18* | .09 | .11 | -- | ||||

| 7. Sexual coercion victimization | 0.76 | (0.96) | 0 – 5 | .05 | .68** | .15* | .20** | .07 | .23** | -- | ||

| 8. TSI trauma | 51.67 | (12.86) | 34 – 102 | .16* | .29** | .29** | .24** | .32** | .27** | .31** | -- | |

| 9. TSI self-dysfunction | 32.41 | (7.04) | 26 – 64 | .14* | .30** | .21** | .25** | .20** | .17* | .32** | .70** | -- |

| 10. TSI dysphoria | 43.93 | (11.15) | 27 – 81 | .09 | .24** | .26** | .30** | .31** | .13 | .24** | .79** | .69** |

Note. CSA = child sexual abuse, TSI = Trauma Symptom Inventory.

p < .01

p < .05.

CSA and Sexual Victimization in Marriage

Actor effects

As hypothesized, results indicate that women with a history of CSA experienced more acts of sexual coercion (i.e., revictimization) by their husbands during the past year than women without a history of CSA (b = .62, p < .01). However, among men, a history of CSA was not associated with experiencing sexual coercion in marriage (b = 0.00, p = 0.99).

Partner effects

Results also revealed a significant partner effect, such that wives with a history of CSA were more likely to engage in sexual coercion against their husbands (b = 0.62, p < .01). Husbands with a history of CSA were not more likely to sexually coerce against their wives (b = −0.44, p = .34).

TSI Trauma Symptoms

Results for the APIM model examining the effects of CSA and sexual coercion victimization on TSI trauma symptoms are displayed in Table 2. The dependent variables had the following R2 values for explained variance by the model: women’s trauma symptoms (R2 = .20, SE = .07, p < .01) and men’s TSI trauma symptoms (R2 = .17, SE = .06, p < .01).

Table 2.

APIM results for child sexual abuse and sexual coercion victimization predicting TSI trauma symptoms.

| Variable | Actor effects: W→W | Partner effects: M→W | Actor effects: M→M | Partner effects: W→M | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Child sexual abuse | 1.82 | 2.19 | 10.54** | 2.84 | 13.93** | 3.85 | 7.26* | 3.30 |

| Sexual coercion victimization | 0.75 | 1.35 | 2.47 | 1.54 | 5.25** | 1.70 | −0.16 | 1.15 |

| Child sexual abuse x sexual coercion victimization | 4.83** | 1.86 | −8.30* | 3.97 | −4.15 | 4.78 | −3.09 | 2.28 |

Note. We fit the distinguishable or fully saturated model (i.e., df = 0), which allowed actor and partner effects to vary across men’s (M) and women’s (W) trauma symptoms.

p < .01

p < .05.

Actor effects

The interaction between women’s CSA and women’s sexual coercion victimization was a significant predictor of women’s TSI trauma symptoms (b = 4.83, p < .01), revealing that among women who experienced CSA, the relationship between women’s sexual victimization in marriage and trauma symptoms was stronger (see Figure 1). Specifically, among women who experienced CSA, women’s sexual victimization positively predicted women’s TSI trauma symptoms (b = 5.57, p < .01), but among women who did not experience CSA, women’s sexual victimization did not predict TSI trauma symptoms (b = 0.74, p = .58).

Figure 1.

The impact of the interaction between women’s CSA and women’s sexual coercion victimization on women’s trauma symptoms.

Men with a history of CSA had higher TSI trauma symptoms (b = 13.93, p < .001) and men’s sexual coercion victimization was related to higher TSI trauma symptoms (b = 5.25, p < .01). However the interaction between men’s CSA and men’s sexual victimization was not significant in predicting men’s TSI trauma symptoms.

Partner effects

The interaction between men’s CSA and men’s sexual coercion victimization negatively predicted women’s TSI trauma symptoms (b = −8.30, p < .05), revealing that among men who experienced CSA, the relationship between men’s sexual victimization and women’s trauma symptoms was more negative. However, the relationship between men’s coercion victimization and women’s TSI trauma symptoms was not significant among men who experienced no CSA (b = 2.47, p = .11), or among men who did experience CSA (b = −5.83, p = .16). Men had greater TSI trauma symptoms when their wives had experienced CSA (b = 7.26, p < .05). No other significant partner effects were found for men’s TSI trauma symptoms.

TSI Self-Dysfunction Symptoms

Results for the APIM model examining the effects of CSA and sexual coercion victimization on TSI self-dysfunction symptoms are displayed in Table 3. The dependent variables had the following R2 values for explained variance by the model: women’s self-dysfunction symptoms (R2 = .18, SE = .08, p < .05), and men’s TSI self-dysfunction symptoms (R2 = .08, SE = .04, p = .06).

Table 3.

APIM results for child sexual abuse and sexual coercion victimization predicting TSI self-dysfunction symptoms.

| Variable | Actor effects: W→W | Partner effects: M→W | Actor effects: M→M | Partner effects: W→M | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Child sexual abuse | −1.54 | 1.27 | 4.32 | 2.96 | 5.31* | 2.37 | 0.31 | 1.43 |

| Sexual coercion victimization | 0.32 | 0.61 | 1.38 | 0.80 | −0.22 | 0.90 | 1.32 | 0.82 |

| Child sexual abuse x sexual coercion victimization | 3.19** | 1.22 | −2.09 | 3.87 | 0.51 | 3.40 | 0.23 | 1.21 |

Note. We fit the distinguishable or fully saturated model (i.e., df = 0), which allowed actor and partner effects to vary across men’s (M) and women’s (W) trauma symptoms.

p < .01

p < .05.

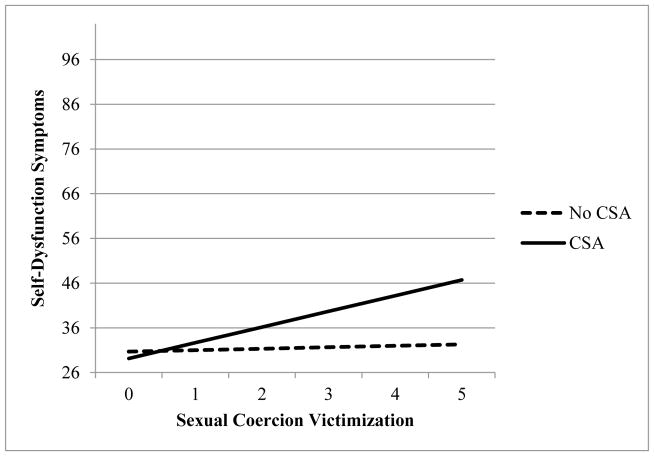

Actor effects

The interaction between women’s CSA and women’s sexual coercion victimization positively predicted women’s self-dysfunction symptoms (b = 3.19, p < .01), revealing that among women who experienced CSA, the relationship between women’s sexual victimization and self-dysfunction symptoms was stronger (see Figure 2). Specifically, among women who experienced CSA, women’s sexual victimization positively predicted women’s self-dysfunction symptoms (b = 3.51, p < .01), but among women who did not experience CSA, sexual victimization did not predict women’s self-dysfunction symptoms (b = 0.32, p = .60).

Figure 2.

The impact of the interaction between women’s CSA and women’s sexual coercion victimization on women’s self-dysfunction symptoms.

Men with a history of CSA had higher self-dysfunction symptoms (b = 5.31, p < .05). However men’s sexual coercion victimization and the interaction between men’s CSA and men’s sexual victimization were not significant in predicting men’s self-dysfunction symptoms.

Partner effects

No significant partner effects were found when predicting TSI self-dysfunction symptoms.

TSI Dysphoria

Results for the APIM model examining the effects of CSA and sexual coercion victimization on TSI dysphoria symptoms are displayed in Table 4. The dependent variables had the following R2 values for explained variance by the model: women’s dysphoria symptoms (R2 = .20, SE = .07, p < .01), and men’s TSI dysphoria symptoms (R2 = .11, SE = .05, p < .05).

Table 4.

APIM results for child sexual abuse and sexual coercion victimization predicting TSI dysphoria symptoms.

| Variable | Actor effects: W→W | Partner effects: M→W | Actor effects: M→M | Partner effects: W→M | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Child sexual abuse | −1.39 | 2.19 | 7.43 | 4.55 | 5.69 | 3.11 | 2.03 | 2.14 |

| Sexual coercion victimization | 0.51 | 1.21 | 2.05 | 1.36 | 2.71** | 1.01 | −1.21 | 0.96 |

| Child sexual abuse x sexual coercion victimization | 3.72* | 1.59 | −9.26** | 3.38 | 4.23 | 5.43 | −0.31 | 1.56 |

Note. We fit the distinguishable or fully saturated model (i.e., df = 0), which allowed actor and partner effects to vary across men’s (M) and women’s (W) trauma symptoms.

p < .01

p < .05.

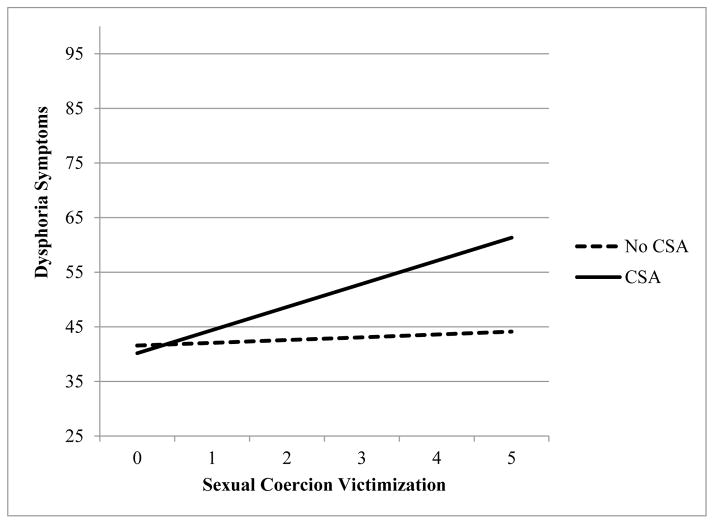

Actor effects

Among women, the interaction between women’s CSA and sexual coercion victimization positively predicted women’s dysphoria symptoms (b = 3.72, p < .05), revealing that among women who experienced CSA, the relationship between women’s sexual victimization and dysphoria symptoms was stronger (see Figure 3). Among women who experienced CSA, women’s sexual victimization positively predicted women’s dysphoria symptoms (b = 4.23, p < .01), but among women who did not experience CSA, sexual victimization did not predict women’s dysphoria symptoms (b = 0.51, p = .67).

Figure 3.

The impact of the interaction between women’s CSA and women’s sexual coercion victimization on women’s dysphoria symptoms.

Men’s sexual coercion victimization was positively related to men’s dysphoria symptoms (b = 2.71, p < .01). However, men’s sexual coercion victimization and the interaction between men’s CSA and men’s sexual victimization were not significant in predicting men’s dysphoria symptoms.

Partner effects

The interaction between men’s CSA and men’s coercion victimization negatively predicted women’s TSI dysphoria symptoms (b = −9.26, p < .01), revealing that among men who experienced CSA, the relationship between men’s sexual victimization and women’s dysphoria symptoms was more negative. Specifically, the relationship between men’s coercion victimization and women’s TSI dysphoria symptoms was not significant among men who experienced no CSA (b = 2.05, p = .13), but was negatively significant among men who experienced CSA (b = −7.20, p < .05). No other significant partner effects were found.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the occurrence of sexual revictimization exclusively in a sample of heterosexual married couples. Compared to those with no CSA history, women who experienced early sexual abuse were at greater risk of being sexually revictimized by their husbands during the early stages of marriage. These revictimization experiences were in turn associated with more severe trauma symptoms for women. Among husbands with a history of CSA, sexual coercion victimization was negatively associated with their wives’ trauma and dysphoria symptoms.

Prior literature has found evidence of revictimization in non-marital intimate relationships (e.g., Daigneault et al., 2009; Jaffe et al., 2012; Testa et al., 2007). The present study adds to this work by suggesting that sexual revictimization may extend to the marital dyad. Specifically, for women with a history of CSA, rather than serving as a safe haven, the marital relationship may pose a threat for further victimization. The notion that revictimization may emanate from within the marital relationship violates foundational assumptions of trust and security between partners, and is concerning in light of the many emotional, financial, and legal ties that bind spouses to each other. This finding also supports the robust nature of sexual revictimization more generally and suggests that, for women with a history of CSA, the newlywed period may not be characterized by the high levels of satisfaction typical of other new marriages (Lavner et al., 2012). Indeed, prior studies indicate that marital satisfaction is lower when one partner has experienced prior sexual abuse (e.g., DiLillo et al., 2009).

In contrast to women, however, CSA history among men was not associated with sexual revictimization in marriage. This finding differs from prior work documenting that men are generally at risk for sexual revictimization (e.g., Desai et al., 2002). Although the rate of CSA found here (6.5%) is consistent with larger studies of male CSA (Pereda et al., 2009), the relatively few men reporting these experiences (n = 13) may have hindered our ability to detect increased risk for revictimization in this group.

Revictimization is known to have a cumulative impact on psychological functioning (e.g., Classen et al., 2005). Consistent with this notion, present findings indicate that sexual coercion victimization in marriage was associated with increased psychological symptoms among women who had previously been victimized. These symptoms encompassed a wide range of difficulties, including intrusive memories, avoidance, dissociation, sexual concerns, maladaptive coping, and high negative affect. Although sexual assault at the hands of a stranger or acquaintance is more frequently studied, assault by a spouse may be characterized by distinct pathogenic qualities that violate the fundamental tenets of marriage as a union between two trusting partners. Individuals with a history of sexual abuse may have existing difficulties placing trust in a romantic partner (DiLillo & Long, 1999). These difficulties may be exacerbated by the experience of revictimization by a spouse, which may contribute to the elevated trauma symptoms seen here. Moreover, trauma symptoms have been associated with poorer relationship quality in undergraduates (Davis, Petretic-Jackson, & Ling, 2001), as well as relationship distress, conflict, dissatisfaction, and reduced intimacy in veterans (see Dekel & Monson, 2010). If revictimization were to continue beyond the first year of marriage, when satisfaction typically decreases, even among non-violent couples (e.g., Lorber, Erlanger, Heyman, & O’Leary, 2015; Mitnick, Heyman, & Smith Slep, 2009), this could lead to an accelerated erosion of marital satisfaction and, potentially, a further exacerbation of wives’ trauma symptoms.

Although unanticipated, we found that, among husbands with a history of CSA, sexual coercion victimization was negatively associated with their wives’ trauma and dysphoria symptoms. While the reason for this finding is unclear, it is possible that husbands who have personally experienced both CSA and sexual coercion in marriage may be less likely to perpetrate sexually coercive acts toward their wives. In turn, these wives may experience less violence in the marriage than other couples, and therefore may be less likely to endorse trauma-related symptoms. Further research is needed to explore this possibility.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, reflecting its Midwestern location, the current sample of newlywed couples was predominately European American and entirely heterosexual. To determine whether the current findings generalize to newlywed couples more broadly, future studies should include more ethnically diverse samples, as well as same sex marital couples. A second limitation is the use of retrospective self-reports of child sexual abuse. Although such reports are well entrenched in this literature (see Hulme, 2004) and reasonably accurate in identifying prior documented abuse (Goodman et al., 2003), recollections of sexual victimization may be subject to distortions, particularly underreporting due to difficulties in recall or intentional withholding (Widom & Morris, 1997). Third, the cross-sectional approach used here precludes causal interpretations or conclusions about the temporal ordering of variables. Although by definition child sexual abuse precedes sexual coercion in marriage, the timing of onset of trauma symptoms remains unclear. It is possible, for example, that trauma symptoms may precede and contribute to sexual victimization in marriage. This possibility should be considered in future longitudinal studies.

Future Directions

Future research can build on the present findings in a number of ways. An important next step will be to consider mechanisms accounting for the linkages found here between early sexual victimization and sexual coercion in marital relationships. For example, disclosure of one’s CSA history to a spouse—and spousal reactions to those disclosures—may be key to understanding marital revictimization. A lack of disclosure or negative spousal reactions to learning of a partner’s abuse (e.g., not believing or blaming a spouse) may contribute to risk for revictimization. On the other hand, supportive responses from spouses may buffer against not only revictimization but also the victim’s individual trauma symptoms (Evans, Steel, Watkins, & DiLillo, 2014). Research supporting this possibility would suggest the need for intervention that helps couples discuss past victimization in ways that validate each other’s needs.

Other forms of child maltreatment often co-occur with sexual abuse and can have a cumulative impact on later functioning (e.g., Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003). Future research should include assessments of a wider range of maltreatment experiences, including physical and psychological abuse, and neglect, in order to explore the interactive effects of these experiences on subsequent victimization in the marital dyad. Moreover, given that sexual coercion in marriage is often accompanied by physical and psychological partner violence (Black et al., 2011), additional research is needed to clarify whether child sexual abuse is also a risk factor for other forms of partner violence in newlyweds. Finally, it would be informative to know whether the sexual coercion reported in the current couples began prior to marriage. If so, this would suggest the need for earlier intervention to address these concerns before marriage and potentially consider issues of mate selection.

Clinical Implications

Successful intervention to address sexual (re)victimization in marriage is predicated on accurate assessment of these behaviors, which may be hindered by a variety of factors, including: a victim’s desire to maintain family privacy, concern about social or economic repercussions of disclosure, and difficulty identifying the experiences as assaultive (Mahoney & Williams, 1998). Clinicians working with women who have experienced CSA should be cognizant of these factors and must be prepared to inquire about the occurrence of sexual assault by a spouse. In extreme cases, victims may need assistance with safety planning to remove themselves from sexually assaultive situations. In less severe instances, however, individuals may not perceive themselves to be in a sexually coercive relationship and instead emphasize broader sexual dysfunction or miscommunication. In these situations, gathering behaviorally-specific and contextual information about key events may help clinicians to differentiate between violent acts, milder instances of coercion, and miscommunication or other sexual dysfunction. Regardless, it is crucial for clinicians to support victims through validation of their experiences. Couples-based approaches to intervention should include efforts to foster sensitivity toward CSA experiences and increase awareness among partners that certain sexual tactics may constitute sexual coercion and could lead to increased trauma symptoms in a partner with prior CSA. Finally, particularly when a wife has experienced CSA, couples may also benefit from assistance with clarifying expectations about sex within the marriage, including what constitutes acceptable versus coercive sexual relations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant K01 MH066365 awarded to the first author (DD).

Footnotes

The relationship of perpetrators to male sexual assault victims is difficult to determine given low prevalence rates (Black et al., 2011; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000).

Mplus does not allow for missing data on predictor variables (observed covariates). Therefore, three couples who were missing data on CSA history and one couple was missing data on sexual victimization in marriage were excluded from all analyses. Although an additional two men and one woman were missing data on trauma symptoms, these individuals could be retained in analyses due to the use of maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR).

We also attempted to model a negative binomial distribution APIM, but this model would not estimate, most likely due to the complex nature of the model (in addition to estimating the dummy factor as described above, the negative binomial distribution includes a dispersion parameter). Because this model did not converge, we estimated a model with a negative binomial distribution and removed the correlation between the residuals of the two outcomes. This negative binomial model had equivalent findings to the Poisson APIM and thus we report the Poisson APIM results.

Contributor Information

David DiLillo, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Anna E. Jaffe, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Laura E. Watkins, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

James Peugh, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Amanda Kras, Albany Stratton VA Medical Center.

Christopher Campbell, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

References

- Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. Vol. 135. New York: Wiley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM. Sexual revictimization and PTSD: An exploratory study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1999;8:49–65. doi: 10.1300/J070v08n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bachand LL, Caron SL. Ties that bind: A qualitative study of happy long-term marriages. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2001;23:105–121. doi: 10.1023/A:1007828317271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. Human mate selection. American Scientist. 1985;73:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun KS, Bernat JA, Clum GA, Frame CL. Sexual coercion and attraction to sexual aggression in a community sample of young men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:392–406. doi: 10.1177/088626097012003005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL. Association between childhood sexual abuse and adult sexual victimization in a representative sample in Hong Kong Chinese. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, … Zirakzadeh A. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2010;85:618–629. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxell A, King M, Mezey G, Gordon D. Lifetime prevalence, characteristics, and associated problems of non-consensual sex in men: Cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:846–850. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7187.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault I, Hébert M, McDuff P. Men’s and women’s childhood sexual abuse and victimization in adult partner relationships: A study of risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JL, Petretic-Jackson PA. The impact of child sexual abuse on adult interpersonal functioning: A review and synthesis of the empirical literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5:291–328. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(99)00010-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JL, Petretic-Jackson PA, Ling T. Intimacy dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: Long-term correlates of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:63–79. doi: 10.1023/A:1007835531614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel R, Monson CM. Military-related post-traumatic stress disorder and family relations: Current knowledge and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Arias I, Thompson MP, Basile KC. Childhood victimization and subsequent adult revictimization assessed in a nationally representative sample of women and men. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:639–653. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, DeGue S, Kras A, Di Loreto-Colgan AR, Nash C. Participant responses to retrospective surveys of child maltreatment: Does mode of assessment matter? Violence and Victims. 2006;21:410–424. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Fortier MA, Hayes SA, Trask E, Perry AR, Messman-Moore T, … Nash C. Retrospective assessment of childhood sexual and physical abuse: A comparison of scaled and behaviorally specific approaches. Assessment. 2006;13:297–312. doi: 10.1177/1073191106288391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Hayes-Skelton SA, Fortier MA, Perry AR, Evans SE, Messman Moore TL, … Fauchier A. Development and initial psychometric properties of the Computer Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI): A comprehensive self-report measure of child maltreatment history. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Long PJ. Perceptions of couple functioning among female survivors of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1999;7(4):59–76. doi: 10.1300/J070v07n04_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Peugh J, Walsh K, Panuzio J, Trask E, Evans S. Child maltreatment history among newlywed couples: A longitudinal study of marital outcomes and mediating pathways. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:680–692. doi: 10.1037/a0015708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- du Fort GG, Kovess V, Boivin J. Spouse similarity for psychological distress and well-being: A population study. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24:431–447. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700027409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:203–211. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SE, Steel AL, Watkins LE, DiLillo D. Childhood exposure to family violence and adult trauma symptoms: The importance of social support from a spouse. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:527–536. doi: 10.1037/a0036940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM, Polusny MA, Bechtle AE, Naugle AE. Cumulative trauma: The impact of child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:25–35. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman G, Ghetti S, Quas J, Edelstein R, Alexander K, Redlich A, … Jones D. A prospective study of memory for child sexual abuse: New findings relevant to the repressed–memory controversy. Psychological Science. 2003;14:113–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K, Weed NC, Butcher JN. Dyadic agreement on the MMPI-2. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:603–615. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00222-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PA. Retrospective measurement of childhood sexual abuse: A review of instruments. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:201–217. doi: 10.1177/1077559504264264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Cranston CC, Shadlow JO. Parenting in females exposed to intimate partner violence and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2012;21:684–700. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2012.726698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalick SM, Hamilton TE. The matching hypothesis reexamined. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:673–682. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.4.673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns JN, Leonard KE. Social networks, structural interdependence, and marital quality over the transition to marriage: A prospective analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:383–395. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Models of nonindependence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13:279–294. doi: 10.1177/0265407596132007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Bradbury TN, Karney BR. Incremental change or initial differences? Testing two models of marital deterioration. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:606–616. doi: 10.1037/a0029052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Das Eiden R. Husband’s and wife’s drinking: Unilateral or bilateral influences among newlyweds in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;(Supp 13):130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, Erlanger AE, Heyman RE, O’Leary KD. The honeymoon effect: Does it exist and can it be predicted? Prevention Science. 2015;16:550–559. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes HM, Neale MC, Kendler KS, Hewitt JK, Silberg JL, Foley DL, … Eaves LJ. Assortative mating for major psychiatric diagnoses in two population-based samples. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:1389–1401. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798007326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney P, Williams LM. Sexual assault in marriage: Prevalence, consequences, and treatment of wife rape. In: Jasinski JL, Williams LM, Jasinski JL, Williams LM, editors. Partner violence: A comprehensive review of 20 years of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. pp. 113–162. [Google Scholar]

- Maniglio R. The role of child sexual abuse in the etiology of substance-related disorders. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2011;30:216–228. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2011.581987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing JT, La Flair L, Cavanaugh CE, Kanga MR, Campbell JC. Testing posttraumatic stress as a mediator of childhood trauma and adult intimate partner violence victimization. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2012;21:792–811. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2012.686963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Brown AL, Koelsch LE. Posttraumatic symptoms and self-dysfunction as consequences and predictors of sexual revictimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:253–261. doi: 10.1002/jts.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:537–571. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ, Siegfried NJ. The revictimization of child sexual abuse survivors: An examination of the adjustment of college women with child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and adult physical abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:18–27. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick DM, Heyman RE, Smith Slep AM. Changes in relationship satisfaction across the transition to parenthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:848–852. doi: 10.1037/a0017004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PF, Cooper L, Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK, … Martin NG. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: Results from a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Griffin MG. How well does cognitive-behavioral therapy treat symptoms of complex PTSD? An examination of child sexual abuse survivors within a clinical trial. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:351–355. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ. Sociodemographic differentials in mate selection preferences. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:928–940. doi: 10.2307/352998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M. The impact of men’s alcohol consumption on perpetration of sexual aggression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1239–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA. Prospective prediction of women’s sexual victimization by intimate and nonintimate male perpetrators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:52–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden F, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Peter-Hagene LC. Longitudinal relationships of social reactions, PTSD, and revictimization in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016;31:1074–1094. doi: 10.1177/0886260514564069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Danielson CK, McCauley JL, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. National prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among sexually revictimized adolescent, college, and adult household-residing women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:935–942. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, Part 2: Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]