Abstract

Background and objectives

Patients with CKD are asked to perform self-management tasks including dietary changes, adhering to medications, avoiding nephrotoxic drugs, and self-monitoring hypertension and diabetes. Given the effect of aging on functional capacity, self-management may be especially challenging for older patients. However, little is known about the specific challenges older adults face maintaining CKD self-management regimens.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study designed to understand the relationship among factors facilitating or impeding CKD self-management in older adults. Six focus groups (n=30) were held in August and September of 2014 with veterans≥70 years old with moderate-to-severe CKD receiving nephrology care at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Grounded theory with a constant comparative method was used to collect, code, and analyze data.

Results

Participants had a mean age (range) of 75.1 (70.1–90.7) years, 60% were black, and 96.7% were men. The central organizing concept that emerged from these data were managing complexity. Participants typically did not have just one chronic condition, CKD, but a number of commonly co-occurring conditions. Recommendations for CKD self-management therefore occurred within a complex regimen of recommendations for managing other diseases. Participants identified overtly discordant treatment recommendations across chronic conditions (e.g., arthritis and CKD). Prioritization emerged as one effective strategy for managing complexity (e.g., focusing on BP control). Some patients arrived at the conclusion that they could group concordant recommendations to simplify their regimens (e.g., protein restriction for both gout and CKD).

Conclusions

Among older veterans with moderate-to-severe CKD, multimorbidity presents a major challenge for CKD self-management. Because virtually all older adults with CKD have multimorbidity, an integrated treatment approach that supports self-management across commonly occurring conditions may be necessary to meet the needs of these patients.

Keywords: geriatric nephrology; self-management; chronic kidney disease; adult; African Americans; blood pressure; comorbidity; diabetes mellitus; focus groups; gout; grounded theory; humans; hypertension; male; nephrology; qualitative research; renal insufficiency, chronic; self care; veterans

Introduction

Moderate-to-severe CKD defined as an eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 disproportionately affects older adults (1,2). At this level of reduced eGFR, achieving CKD self-management as recommended by clinical practice guidelines may require that patients make dietary and lifestyle changes, take multiple daily medications, avoid certain over-the-counter drugs, and self-monitor co-occurring chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes (3). Chronic disease self-management programs have the potential to slow CKD progression or improve management of CKD risk factors (4–7). However, qualitative studies have identified barriers to self-management including lack of knowledge about self-management, poor coping mechanisms, and lack of social support (8,9). Because both CKD and older age are associated with reduced functional capacity (10,11), self-management may be especially challenging for these patients. The purpose of this study was to identify and describe the relationship among factors that facilitate or impede CKD self-management for older veterans with moderate-to-severe CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participant Selection

We conducted an exploratory qualitative study designed to obtain patients’ perspectives on CKD self-management. Six focus groups were conducted in August and September of 2014 to elicit a broad range of views and allow for interactive discussion. Participants were recruited from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center Renal Clinic. Patients were eligible to participate if they were ≥70 years old, had a diagnosis of CKD, had been seen in the Renal Clinic ≥2 occasions, had available data on eGFR, and had an eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Exclusions included dementia diagnosis, Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test score ≥10, and self-reported hearing or visual impairment. The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent. Our analysis and manuscript preparation was informed by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative studies (Supplemental Table 1) (12,13).

Prior studies have shown considerable heterogeneity in CKD progression and identified uncertainty about the expected trajectory of CKD as an important concern for patients (14–16). Because self-management education may be provided in the context of CKD progression, rather than CKD stage alone (17), we categorized potential participants into three CKD trajectories in order to represent a variety of CKD patient experiences while facilitating conversation among patients in similar situations. Trajectories included: stable (rate of decline <2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year, total decrease not >4.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and no decline by >8 ml/min per 1.73 m2 between any two measurements), linear decline (consistent rate of decline >4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year throughout available follow-up and total decline ≥8 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and nonlinear (all other trajectories). We adapted trajectory definitions from prior studies and available electronic health record eGFR data from the prior 3 years (14).

We mailed letters to 108 Renal Clinic patients to announce the study, and inform them that we would be contacting them by phone to determine their interest in participation (Supplemental Figure 1). Participants were recruited until we scheduled five to eight individuals for each of the six focus groups (two groups per CKD trajectory). Of 64 patients contacted by phone, 14 patients declined to participate because they were not interested, five reported transportation difficulty/lived too far away, and three declined because of active health problems. Two patients were not eligible because of self-reported impairments in vision, and eight were interested in participation but had conflicts on the scheduled focus group dates. Two patients did not attend the scheduled focus groups. Altogether, 30 veterans participated (47% of those contacted by phone).

Data Collection

Each participant reported marital status, race, ethnicity, and family income. Health literacy, kidney disease self-efficacy, and perceptions of social support were measured using validated brief instruments (18–23). Community mobility was assessed using the life-space mobility assessment (24). Self-rated health was assessed as part of the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form (25). Age, medical history, health care utilization, and laboratory values were obtained from the VA electronic health record using a standardized chart abstraction method.

Focus groups were led by the last author (K.V.E.). Each focus group followed a semistructured facilitator’s guide (Supplemental Table 2). The guide was developed by the first and last authors (C.B.B. and K.V.E.) and refined on the basis of feedback from the target population and included the following topics: experience living with CKD, physician-recommended self-management tasks, and barriers and facilitators to performing those activities. The facilitator probed to support discussion of specific self-management tasks for sodium and fluid management, dietary restrictions (potassium, phosphorus, and protein), medications management, and avoiding nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Not all participants would have experience with each of these tasks, therefore we aimed to elicit challenges with self-management tasks in cases in which these had been recommended.

Statistical Analyses

Consistent with the grounded theory (26), we used a constant comparative method to simultaneously collect, code, and analyze data. We used Nvivo 10 to assist with data management. The second author (A.V.) led the formal data analysis, which began after audio-recorded focus groups were transcribed verbatim. In the first stage, known as open coding, she assigned a name to each coherent idea within the interview transcripts. In the second stage, known as focused coding, she grouped frequent and significant codes into conceptual categories with a range that described most of the responses. Factors that shaped self-management, including symptoms, social support, and self-efficacy, were also identified and later grouped into larger domains.

At this stage, we considered the emergent fit between this final set of concepts and relevant frameworks of functioning (27–29). In doing so, we discovered that our domains influencing self-management bore similarities to those of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). The ICF framework conceptualizes functioning as a dynamic interaction among a person’s health condition (disorder or disease), their personal factors, and their environmental factors. Functioning itself is defined at the level of the body (“Body Function and Structures”), the whole person (“Activity”), and the whole person in a social context (“Participation”) (30). The ICF framework has been applied to functional activity in a variety of ways, including characterizing specific patient populations, identifying factors to promote health behaviors, and designing housing to enhance inclusion of specific disabled populations (31–33).

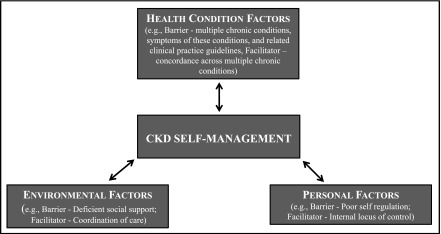

Because our focus was specifically on the functional outcome of self-management within the context of a specific disease, CKD, we eliminated all functional domains except Activity, and defined this domain more specifically as CKD Self-Management (Figure 1). ICF conceptualizes the influences on Activity as Environmental Factors (including social support) and Personal Factors (such as coping styles), and Health Condition (disorder or disease) (30,34). We saw that our data readily grouped similarly into Environmental Factors and Personal Factors. However, we found that Health Condition was more than one disorder or disease in the case of these older patients. Moreover, there was no place in the model to account for the instructions patients with CKD were receiving as part of their care in the context of having multiple chronic conditions. As with Environment and Personal, Health Condition was a whole constellation of contextual factors including multiple chronic conditions, symptoms of these conditions, and their related clinical practice guidelines. We therefore broadened this domain and renamed it Health Condition Factors. The central organizing concept that emerged from the data was managing complexity.

Figure 1.

The “Managing Complexity in CKD Self-Management” model shows Health Condition Factors, Environmental Factors, and Personal Factors dynamically interacting to facilitate or impede the functional “Activity” of CKD self-management. Example barriers and facilitators are provided for each factor.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants had a mean age (range) of 75.1 (70.1–90.7) years, 60% were black, and all but one participant (96.7%) were men. The majority of participants (86.7%) had an eGFR<45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 on the most recent clinically obtained laboratory work. In addition to CKD, a majority of participants had co-occurring hypertension (90.0%), arthritis (73.3%), diabetes (66.7%), and gout (53.3%). All participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of focus group participants (n=30)

| Characteristics | Median (Range) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 75.1 (70.1–90.7) |

| Black race | 18 (60.0) |

| Men | 29 (96.7) |

| Income<$20,000/yr | 10 (33.3) |

| Low health literacya | 7 (23.3) |

| Confidenceb | 10.5 (6.0–18.0) |

| Life-space mobilityc | 76.0 (43.5–120.0) |

| Married | 15 (50.0) |

| Social supportd | 20.0 (12.0–25.0) |

| Self-reported health (excellent, very good, good) | 17 (56.7) |

| Hypertension | 27 (90.0) |

| Diabetes | 20 (66.7) |

| Heart failure | 7 (23.3) |

| Arthritis | 22 (73.3) |

| Gout | 16 (53.3) |

| Depression/PTSD | 6 (20.0) |

| Number of medications | 12.5 (3.0–29.0) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | |

| 45–59 | 4 (13.3) |

| 30–44 | 18 (60.0) |

| <30 | 8 (26.7) |

| CKD trajectory | |

| Stable | 9 (30.0) |

| Linear decline | 10 (33.3) |

| Nonlinear | 11 (36.7) |

| Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, mg/g | |

| <30 | 15 (50) |

| 30–299 | 8 (26.7) |

| ≥300 | 7 (23.3) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.9 (9.3–16.8) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.6 (2.9–4.1) |

| Serum potassium, mEq/L | 4.1 (3.0–5.1) |

| Serum bicarbonate, mEq/L | 27.5 (20.0–38.0) |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dl | 3.6 (2.3–5.1) |

| Serum intact PTH, pg/ml | 80 (37.8–359.1) |

| Nephrology care, yr | 3.3 (0.3–12.9) |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Health literacy screening defined as “somewhat, a little bit, or not at all” when asked “how confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?” (15,19,20).

Self-reported confidence in CKD-related self-management tasks. Scores range from 6 to 30 with higher scores indicating lower confidence (16).

Life-space assessment measures of how far, how frequent, and amount of assistance needed when moving through one’s environment in the last 4 weeks. Scores range from 0 (bedbound) to 120 (beyond one’s town without the use of an assistive device or help from another person) (21).

Barriers and Facilitators to CKD Self-Management

Older adults with CKD experience multiple challenges maintaining CKD self-management regimens. Barriers were related to the interaction between Health Condition Factors, contextual Environmental Factors, and contextual Personal Factors (Figure 1). Barriers and facilitators to CKD self-management by the number of focus groups in which they were discussed are displayed in Table 2. These findings were similar across CKD trajectory groups.

Table 2.

Barriers and facilitators to CKD self-management by ICF domain and number of focus groups reporting

| Barriers and Facilitators | Number of Focus Groups |

|---|---|

| Health condition factors | |

| Symptoms | |

| Barrier: Asymptomatic nature of CKD | 6 |

| Barrier: Symptoms across multiple chronic conditions | 5 |

| Treatment advice | |

| Barrier: Unclear treatment goals | 6 |

| Barrier: Unclear treatment regimen | 5 |

| Barrier: Discordance across multiple chronic conditions | 5 |

| Facilitator: Concordance across multiple chronic conditions | 5 |

| Facilitator: Prioritization of health conditions | 4 |

| Personal factors | |

| Self-regulation | |

| Barrier: Poor self-regulation | 6 |

| Facilitator: Planning and organization | 5 |

| Facilitator: Adjusting to new tastes and behaviors | 5 |

| Empowerment | |

| Barrier: External locus of control | 5 |

| Barrier: Poor self-efficacy | 1 |

| Facilitator: Information seeking | 6 |

| Facilitator: Identification of self-care alternatives | 4 |

| Facilitator: Internal locus of control | 4 |

| Environmental factors | |

| Support and relationships | |

| Barrier: Deficient social support | 5 |

| Barrier: Deficient provider support | 5 |

| Facilitator: Positive social support | 4 |

| Services, systems, and policies | |

| Barrier: Deficient coordination of care across multiple chronic conditions | 5 |

| Facilitator: Positive provider support | 3 |

| Facilitator: Coordination of care across multiple chronic conditions | 3 |

| Healthy food product market availability | |

| Barrier: Lack of availability and access | 3 |

ICF, World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.

Our simplified, ICF-modified model of care, “Managing Complexity in CKD Self-Management,” emphasizes the effect of Health Condition Factors, Environmental Factors, and Personal Factors on an individual’s capacity to execute an activity, in this case CKD Self-Management. Patients typically did not have just one chronic condition, CKD, but a number of commonly co-occurring conditions including hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, heart failure, or gout. Recommendations for CKD self-management therefore occurred within a complex regimen of recommendations for other diseases (Figure 1, Health Condition Factors box). Focus group participants frequently voiced experiential factors related to CKD. For example, within this complex of diseases the asymptomatic nature of CKD (“I don’t even know if I got it or not, because I can’t tell no difference. They say I have. I don’t know what it feels like. I just don’t know”) made them doubt its existence. Unclear treatment goals (“I’m questioning: Why am I getting all of these medications.... I take my blood sugar, I take my BP…When do I feel better?”) and unclear treatment regimen (“It [doesn’t] seem like there is a lot information available…on what you should do if you’re 20% or 30% [eGFR level]… what you should do and what you shouldn’t do. What you should eat and what you shouldn’t eat. I just haven’t gotten a lot of information”) further downplayed CKD’s importance relative to other conditions.

Patients had differing abilities to cope with complexity on the basis of Personal Factors (Figure 1, Personal Factors box). Adherence to dietary recommendations to reduce sodium was challenged when the patient had poor self-regulation (“it makes it hard because, a lot of times you say well I’m hungry, so there’s a fast food joint, so you go and buy something to eat”) or an external locus of control (“I’m sorry, this is laying it at my doorstep, the patient, it is really too much, it is not my responsibility”). However, respondents stated that self-management can be helped by planning and organization (using pillboxes, measuring out daily water requirements into a large container), adjusting to new tastes and behaviors (egg whites instead of eggs; onions, peppers instead of bacon: “You gotta have something in there to give you taste”), seeking information (“You make a list of the questions you want to ask them [doctors], so you don’t forget them, because they’re rushed”), and an internal locus of control (“with me it’s just a matter of discipline”).

Finally, Environmental Factors added layers of complexity to patients’ self-management activity (Figure 1, Environmental Factors box). In keeping with the ICF, these factors included the patient’s social and medical environment. Participants described wanting to fit into social structures (i.e., families) in which the majority of the group ate high-sodium, high-protein foods and described real pressures of social acceptance. On the other hand, positive social support could aid the patient (“my wife sometimes will prepare different meals for me than she does for herself and my daughter”). When it came to the health care system, patients described deficient provider support (i.e., rushed physicians, little continuity). In addition, whereas patients are often concerned about these interacting factors and their “overall picture,” they described each provider as having a more narrow focus on the relationship between the specific disease and the self-management recommendations of interest to their medical specialty (“I see four doctors here at the VA, so I can never remember who is doing, checking, for what”).

Managing Complexity across Multiple Chronic Conditions

Patients with CKD gave repeated examples of how they attempt to negotiate complexity across multiple chronic conditions (Table 3). Respondents sometimes pointed to overtly discordant treatment recommendations across chronic conditions. For example, patients with both CKD and heart failure face the discordance that “One doctor says drink a lot of water. Another doctor says you’re drinking too much water. Well what is it?” For some, the complexity and personal burden of self-management responsibilities was overwhelming: “[Y]ou really are just presented with a host of things that you have to do…you gotta deal with the kidney, you gotta deal with the back, you gotta deal with the heart. Sometimes you just want to give up. I’m not dealing with any of it…” In some cases, co-occurring conditions such as addiction or post-traumatic stress disorder were unrelated to CKD, but dominated a patient’s time and resources, limiting their ability to address all other self-management tasks.

Table 3.

Reported treatment advice and related self-management situations across comorbid chronic conditions

| CKD Treatment Advice | Comorbidity | Comorbidity Treatment Advice | Self-Management Situation | Examples of Self-Management Conflict |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoid NSAIDs | Arthritis, gout | Take NSAIDs | Discordant | “[L]ast week I had tremendous gout attack in my wrists, I mean it was swoll and I couldn’t, if I try to move my wrist that far, I was in excruciating pain, so I took some Aleve, which I’m not supposed to take, but it relieved the pain that I had, it was the only thing that I had that would relieve the pain” (FG1) |

| “Got a little arthritis and things like that, that I need anti-inflammatories” (FG1) | ||||

| Drink plenty of water | Heart failure | Avoid drinking water | Discordant | “One doctor says drink a lot of water. Another doctor says you’re drinking too much water. Well, what is it?” (FG3) |

| “One of the doctors mentioned the volume of water that I should drink, and then another said ‘Don’t drink very much water; you got too much as it is.’ So I’m caught in between so I just take it when I get thirsty, I get something to drink.” (FG6) | ||||

| “They told me to drink water, a lot of water. But, then my cardiologist told me not to drink too much water.” (FG2) | ||||

| Avoid potassium | Hypokalemia – leg cramps | Take potassium pills Eat high-potassium foods | Discordant | “…but I’ve got to have so many bananas. That’s the way I can keep from getting leg cramps at night” (FG1) |

| “[I]f potassium is a problem for the kidney, why would your doctor give you potassium pills, why? So, evidently that is not affecting my kidneys….Because I take 10 mg of potassium and that is from my doctor.” (FG2) | ||||

| Avoid protein | Gout | Avoid protein | Concordant | “I mostly just reduce the amount of meat. I have gout too like the gentleman number 5 here. Does anyone else have gout here? I just wondered how common it is with kidney problems. Anyhow, I just have to watch these kinds of foods with the gout too.” (FG1) |

| “I have gout also. So I have two things working there. I can’t have steak anymore, because it is red meat and it [also] activates the gout.” (FG3) | ||||

| Take medicine for hypertension | Hypertension | Take medicine for hypertension | Concordant | “That’s what every doctor, my primary care and all, says. The most dangerous thing is BP for kidneys, that’s the most dangerous. If you keep your BP under control that is better for your kidneys.” (FG2) |

| “High BP. If you have to put it to one thing, high BP, that’s what they tell me.... That’s the worst thing in the world, gives you everything. That’s the worst thing in the world.” (FG3) | ||||

| Limit potassium (fruit juices), phosphorus (colas) | Diabetes | Avoid sugar (sugar sweetened beverages) | Concordant | Facilitator: “…has the dietician or doctor told you to cut back on things like bananas?….” |

| “Yeah. Bananas and pineapples. They got so much sugar.” (FG5) | ||||

| “Well in relation to that and your diabetes. They tell you not to drink the colored drinks and try to stay more with clear drinks, and that’s good for your kidneys. Drink mostly water, you know.” (FG6) | ||||

| Adhere to treatment recommendations | Mental health issues (i.e., addiction, PTSD) | Adhere to treatment recommendations | Unrelated | “I’m an addict. I have to acknowledge that, every time I eat, every time I drink. So I have to try and not eat and those things that feed into my addiction…. Stay away from certain things….Salt.” (FG5) |

| “Many veterans today, people who have problems, tend to say if they’re asked, they say ‘I’m ok.’ Well, that’s a lie, you’re not ok, you do have a problem. Like so many guys walking around with the PTSD. They say, ‘I’m ok.’ Well you’re not ok, because you do have a problem.” (FG6) |

We present treatment advice here in lay terms used by focus group participants rather than back-translating participant language into clinical terminology. NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; FG, focus group; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Prioritization emerged as one effective strategy for managing complexity (“The most dangerous thing for kidneys is BP. If you keep your BP under control, that is better for your kidneys”). In addition, some patients would arrive at the conclusion that they could group similar recommendations (i.e., concordant recommendations) to simplify their regimens. For example, avoiding protein consumption because of gout and CKD (“I have two things working there”) effectively addressing two disease recommendations with a single self-management task.

Participants expressed the viewpoint that a health care system environment that considers only one condition at a time does not meet their needs as older adults with multimorbidity. After hearing from the others, one participant concluded that “all of us have multiproblems.” Another stated:

You go to one doctor, or you go the nephrology people…they don’t talk anything about diabetes or your heart or whatever the case may be. Seems like there should be some coordination amongst them, “now wait a minute this guy has a heart problem too what are we gonna do about this,” or “now since he has all three, what kind of instructions are we going to give him?”

With refusals at one dysfunctional extreme of the self-management behavior continuum and total adherence to all recommendations at the other, most patients with CKD expressed living in the middle, struggling somewhat ineffectively to self-manage burdensome complexity.

Discussion

Among veterans ≥70 years old with moderate-to-severe CKD receiving active nephrology care, multimorbidity was reported as a major challenge for CKD self-management. Older adults with CKD must negotiate the complexity that arises when they are asked to adhere to discordant treatment recommendations. They experience this in the context of differing personal abilities to cope with complexity and within a health care environment that is not organized to address multiple chronic conditions. Because virtually all older adults with CKD have multimorbidity, an approach that supports self-management across commonly occurring conditions may be necessary to meet the needs of these patients.

Prior studies have reported barriers to chronic disease self-management among older adults including lack of knowledge regarding chronic disease management, poor self-efficacy, and poor social support (7). Specific to CKD, barriers to self-management tasks have been reported to include poor understanding of CKD-related health risks among patients and poor prioritization of CKD among primary care providers (35). The burden of dietary and fluid restriction in CKD has been previously described in terms of “fighting temptations” and “navigating change” in a thematic synthesis of 41 qualitative studies (9). In the general non-CKD population, presence of multimorbidity has been previously reported by patients to impede chronic disease self-management in several ways. Challenges that arise include the worsening of one condition by the treatment of another condition, being overwhelmed by dominant conditions, and receiving conflicting treatment recommendations (36,37).

Our findings extend those of prior studies in several important ways. ICF is a conceptual framework for functioning that has been used to categorize functional determinants and to design studies to improve function by addressing these. ICF has, however, not been used in considering CKD self-management (30,34). As modified, the ICF-based Managing Complexity in CKD Self-Management model theorizes that Personal Factors, Environmental Factors, and Health Condition Factors dynamically interact to facilitate or impede the functional “Activity” of CKD self-management. The challenges that arise for these patients with CKD were commonly reported when CKD co-occurred with heart failure, arthritis, or gout. Although such conditions commonly co-occur, discordant treatment advice is not explicitly reconciled in routine clinical practice. Patients included in our study suggested solutions for handling the complexity that arises with multimorbidity including prioritizing or reconciling conflicting treatments and bundling similar treatment recommendations for patients with multiple chronic conditions.

There is a growing awareness of the importance of CKD self-management as well as new reimbursement models for CKD education and chronic disease management (35). On the basis of the ICF model, health system interventions that support older adults within their environmental context may improve CKD self-management. A first step is for providers to recognize the possible effect of discordant recommendations on patients’ ability to self-manage CKD, not often acknowledged by the disease-based model of care supported by current CKD clinical practice guidelines. When possible, primary care providers could help patients prioritize treatments on the basis of their preferences and health goals or identify treatment alternatives when CKD limits the treatment of other conditions. Across our focus groups, the asymptomatic nature of CKD was reported as a barrier to CKD self-management, which had important implications when discordant treatment recommendations arose. For example, when faced with decisions about self-medicating for arthritis, patients reported prioritizing pain relief, without discussing this with their nephrologists. Future studies are necessary to identify which disease combinations should be targeted. Innovative models of care that improve coordination across multiple conditions and improve integration of self-management recommendations from nephrology, other specialists, and primary care should be developed and tested.

Although our study had several strengths including a focus on older adults with moderate-to-severe CKD and a sampling strategy that included distinct CKD trajectories, these findings must be interpreted within the context of known limitations. Our sample included older, primarily male veterans from a single VA medical center. In addition, the 47% participation rate and exclusion of patients with vision, hearing, or cognitive impairment or transportation barriers may have resulted in possible bias toward relatively healthier patients with CKD. There is opportunity for further research among those with greater disability or in younger CKD populations. Furthermore, although the number of planned focus groups was informed by prior literature (13,38), homogeneity of the participants (i.e., age, sex, veteran status, CKD trajectory) and complexity of the research questions, the scope of this project, and available resources precluded sampling until we reached theoretic saturation.

In this study of focus groups of older veterans with moderate-to-severe CKD under nephrologists’ care, CKD self-management occurred in the setting of complex multimorbidity. Although patients asked for recommendations that address commonly co-occurring chronic conditions, routine clinical care follows a one-condition-at-a-time approach leaving integration of recommendations across conditions up to patients. Programs to support CKD self-management among older adults should take into account the dynamic relationship between multiple chronic conditions, personal factors, and environmental factors as barriers and facilitators to the successful performance of CKD self-management activities.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support was provided through a Career Development Award Level 2 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (1IK2CX000856-01A1) to C.B.B.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Managing Complexity in Older Patients with CKD,” on pages 559–561.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06850616/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bowling CB, Muntner P: Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease among older adults: A focus on the oldest old. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 1379–1386, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowling CB, Sharma P, Fox CS, O’Hare AM, Muntner P: Prevalence of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate among the oldest old from 1988-1994 through 2005-2010. JAMA 310: 1284–1286, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidle for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen SH, Tsai YF, Sun CY, Wu IW, Lee CC, Wu MS: The impact of self-management support on the progression of chronic kidney disease--a prospective randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3560–3566, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, Rhodes S, Shekelle P: Meta-analysis: Chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Ann Intern Med 143: 427–438, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH: Self-management education programs in chronic disease: A systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med 164: 1641–1649, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K: Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 288: 2469–2475, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Phoon RK, Chadban SJ, Shen Y, Craig JC: Knowledge deficit of patients with stage 1-4 CKD: A focus group study. Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 234–243, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer SC, Hanson CS, Craig JC, Strippoli GF, Ruospo M, Campbell K, Johnson DW, Tong A: Dietary and fluid restrictions in CKD: A thematic synthesis of patient views from qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 559–573, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowling CB, Sawyer P, Campbell RC, Ahmed A, Allman RM: Impact of chronic kidney disease on activities of daily living in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66: 689–694, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Büla CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC: Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: A systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 48: 445–469, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19: 349–357, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A, Winkelmayer WC, Craig JC: Qualitative research in CKD: An overview of methods and applications. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 338–346, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Astor BC, Lewis J, Hu B, Appel LJ, Lipkowitz MS, Toto RD, Wang X, Wright JT Jr, Greene TH: Longitudinal progression trajectory of GFR among patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 504–512, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hare AM, Batten A, Burrows NR, Pavkov ME, Taylor L, Gupta I, Todd-Stenberg J, Maynard C, Rodriguez RA, Murtagh FE, Larson EB, Williams DE: Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 513–522, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosansky SJ: Renal function trajectory is more important than chronic kidney disease stage for managing patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 36: 1–10, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ: Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 36: 588–594, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtin RB, Walters BA, Schatell D, Pennell P, Wise M, Klicko K: Self-efficacy and self-management behaviors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 15: 191–205, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritvo P, Fishcer J, Miller D, Andrews H, Paty D, LaRocca N: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A User’s Manual. The Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers Health Services Research Subcommittee, New York, NY, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL: The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32: 705–714, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, Vanryn M: Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med 23: 561–566, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarkar U, Schillinger D, López A, Sudore R: Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med 26: 265–271, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling CB, Muntner P, Sawyer P, Sanders PW, Kutner N, Kennedy R, Allman RM: Community mobility among older adults with reduced kidney function: A study of life-space. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 429–436, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays R, Kallich J, Mapes D, Coons S, Carter W, Kamberg C: Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SFTM) Version 1.3: A Manual for Use and Scoring, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 1997

- 26.Charmaz K: Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd Ed., London, UK, London Sage Publications, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellstrom I, Nolan M, Lundh U: Awareness context theory and the dynamics of dementia: Improving understanding using emergent fit. Dementia 4: 269–295, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wuest J: Negotiating with helping systems: An example of grounded theory evolving through emergent fit. Qual Health Res 10: 51–70, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glaser BG: Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis, Mill Valley, CA, Sociology Press, 1992, pp 31–37 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jette AM: Toward a common language of disablement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64: 1165–1168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho-Pinto BP, Faria CD: Health, function and disability in stroke patients in the community. Braz J Phys Ther 20: 355–366, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luchauer B, Shurtleff T: Meaningful components of exercise and active recreation for spinal cord injuries. OTJR (Thorofare, NJ) 35: 232–238, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukkay S: Multidisciplinary procedures for designing housing adaptations for people with mobility disabilities. Stud Health Technol Inform 229: 355–362, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization : Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability, and Health, ICF, The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narva AS, Norton JM, Boulware LE: Educating patients about CKD: The path to self-management and patient-centered care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 694–703, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayliss EA, Steiner JF, Fernald DH, Crane LA, Main DS: Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann Fam Med 1: 15–21, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liddy C, Blazkho V, Mill K: Challenges of self-management when living with multiple chronic conditions: Systematic review of the qualitative literature. Can Fam Physician 60: 1123–1133, 2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruseberg A, McDonagh D: Organising and Conducting a Focus Group: Logistics, New York, NY, Taylor and Francis, 2003 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.