Abstract

Background and objectives

Bowel cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related death in people with CKD. Shared decision making regarding cancer screening is particularly complex in CKD and requires an understanding of patients’ values and priorities, which remain largely unknown. Our study aimed to describe the beliefs and attitudes to bowel cancer screening in patients with CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Face to face, semistructured interviews were conducted from April of 2014 to December of 2015 with 38 participants ages 39–78 years old with CKD stages 3–5, on dialysis, or transplant recipients from four renal units in Australia and New Zealand. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the transcripts.

Results

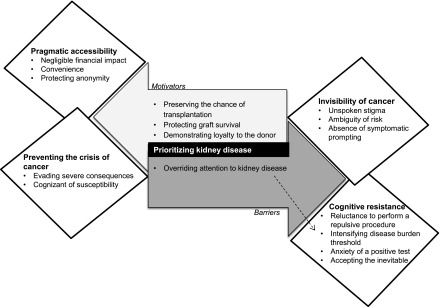

Five themes were identified: invisibility of cancer (unspoken stigma, ambiguity of risk, and absence of symptomatic prompting); prioritizing kidney disease (preserving the chance of transplantation, over-riding attention to kidney disease, protecting graft survival, and showing loyalty to the donor); preventing the crisis of cancer (evading severe consequences and cognizant of susceptibility); cognitive resistance (reluctance to perform a repulsive procedure, intensifying disease burden threshold, anxiety of a positive test, and accepting the inevitable); and pragmatic accessibility (negligible financial effect, convenience, and protecting anonymity).

Conclusions

Patients with CKD understand the potential health benefits of bowel cancer screening, but they are primarily committed to their kidney health. Their decisions regarding screening revolve around their present health needs, priorities, and concerns. Explicit consideration of the potential practical and psychosocial burdens that bowel cancer screening may impose on patients in addition to kidney disease and current treatment is suggested to minimize decisional conflict and improve patient satisfaction and health care outcomes in CKD.

Keywords: bowel cancer screening; chronic kidney disease; kidney transplant recipient; shared-decision making; qualitative research; interview; Anxiety; Attention; Attitude; Australia; Cognition; Early Detection of Cancer; Graft Survival; Humans; kidney; Neoplasms; New Zealand; Patient Satisfaction; renal dialysis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Risk; Transplant Recipients

Introduction

Patients with CKD have a substantially increased risk of cancer. Kidney transplant recipients have up to a fourfold increased risk of developing cancer, and predialysis patients and patients on dialysis have excess risk of 1.5 times compared with the general population (1–3). After urogenital cancers, bowel cancer is the second most common solid organ cancer among people with CKD (4) and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in CKD. The Choosing Wisely Campaign advocates for shared decision making regarding cancer screening in CKD (5), but this is particularly complex given the severity of CKD, the uncertainty of benefit, and the potential complications of screening, which may exacerbate the current condition.

The effects of bowel cancer screening are well established in the general population, but the benefits and harms of screening in CKD are largely unknown (6–12). Patients on dialysis are susceptible to gastrointestinal bleeding due to inflammation of the mucosa, anticoagulation use, and reduced platelet function as a result of uremia; thus, screening may lead to false positive results, requiring follow-up with colonoscopy. There is also increased risk with colonoscopy preparation given the nutritional deficits in patients with CKD (5). Moreover, patients with CKD must manage comorbidities, burdensome treatment responsibilities including polypharmacy, dialysis, appointments, and costs of treatment for CKD, which compounds the complexity of decision making about cancer screening in this setting (13–15).

The lack of empirical evidence about the priorities and perspectives of patients with CKD regarding cancer screening may limit the relevance of the information provided to patients to assist them in making a fully informed choice regarding participation in such a program. As such, the aim of this study was to describe the attitudes and beliefs to bowel cancer screening among patients with CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study reporting is on the basis of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (16).

Participant Selection

Participants were eligible if they were ages >35 years old (given the increased risk compared with age- and sex-matched individuals in the general population) (17); were nondialysis dependent (CKD stages 3–5), were on dialysis (5D), or had received a kidney transplant (5T); and were English speaking. Purposive sampling was used to ensure a range of ages, ethnicities, comorbidities, and exposure to cancer screening (including participants who had been screened and those who had not been screened) and a balance of sex within each CKD stage. Participants were recruited from Australia (Western Sydney Local Health District and Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital) and New Zealand (Christchurch Hospital). Participants were interviewed either in their homes or at the hospital. Ethics approval was obtained from all recruiting hospitals.

Data Collection

An interview guide was developed from current literature and discussed among the research team (Supplemental Table 1). L.J.J. and N.W. conducted face to face semistructured interviews from April of 2014 to December of 2015 until thematic saturation was achieved (that is, no new concepts were raised) within each CKD stage. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Data Analyses

All transcripts were imported into HyperRESEARCH (Version 3.7.1; ResearchWare Inc.) software to facilitate analysis of qualitative data. On the basis of thematic analysis, L.J.J. read the transcripts line by line and coded all meaningful extracts of text into concepts. Similar concepts were then grouped into themes and subthemes. Conceptual patterns among the themes were identified and mapped in a schema. The preliminary findings were discussed among the research team (researcher triangulation) to ensure that the analytic framework captured the depth of data.

Results

Thirty-eight patients ages between 39 and 78 years old (mean =58.7 years old; SD=10.9 years old) participated (83% response rate). Nonparticipation was due to refusal or ill health. The participants had CKD stages 3–5 (n=11; 29%), were on hemodialysis (n=8; 21%), were on peritoneal dialysis (n=3; 8%), or had a kidney transplant (n=16; 42%). Of the 38 participants, 33 (87%) had been tested for the purpose of screening (i.e., had no symptoms), three (8%) had been screened as clinically indicated (on the basis of symptoms, such as bleeding), and two (5%) had never received screening. Thirty-two (84%) participants had completed a fecal immunochemical test (six [15.8%] of which had a positive result), and 22 (58%) had a colonoscopy. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean duration of the interviews was 30 minutes.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=38)

| Characteristics | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 21 | 55.3 |

| Women | 17 | 44.7 |

| Age, yr | ||

| 30–49 | 11 | 28.9 |

| 50–69 | 19 | 50.0 |

| ≥70 | 8 | 21.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 31 | 81.6 |

| Asian | 2 | 5.3 |

| Middle Eastern | 4 | 10.5 |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 1 | 2.6 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Tertiary—university degree | 14 | 36.8 |

| Tertiary—certificate/diploma | 7 | 18.4 |

| Secondary school (grade 12) | 11 | 28.9 |

| Secondary school (grade 10) | 4 | 10.5 |

| Middle school | 2 | 5.3 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 13 | 34.2 |

| Part time | 7 | 18.4 |

| Not employed | 4 | 10.5 |

| Retired | 13 | 34.2 |

| Student | 1 | 2.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/de facto | 25 | 65.8 |

| Separated/divorced | 7 | 18.4 |

| Never married | 4 | 10.5 |

| Widowed | 2 | 5.3 |

| CKD stage | ||

| Stage 3–5 | 11 | 28.9 |

| Hemodialysis | 8 | 21.1 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 3 | 7.9 |

| Transplant | 16 | 42.1 |

| History of cancer | ||

| Yes | 7 | 18.4 |

| No | 31 | 81.6 |

| Family history of bowel cancer | ||

| Yes | 3 | 7.9 |

| No | 35 | 92.1 |

| Previous fecal immunochemical test | ||

| Yes | 32 | 84.2 |

| No | 6 | 15.8 |

| Previous colonoscopy | ||

| Yes | 22 | 57.9 |

| No | 16 | 42.1 |

We identified five major themes: invisibility of cancer, prioritizing kidney disease, preventing the crisis of cancer, cognitive resistance, and pragmatic accessibility. The themes and subthemes are outlined below, with illustrative quotations provided in Table 2. A thematic schema depicting the conceptual patterns and links among themes is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Selected quotations to illustrate each theme

| Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Invisibility of cancer | |

| Unspoken stigma | It’s probably not the sort of thing males talk about when they are having a beer with each other or whatever. I certainly never had—if I’m out fishing or something like that with one of my friends, I’ll never hear him start talking about things like that. (Man, 60s) |

| It’s just not something that you would have come up in a conversation. (Woman, 60s) | |

| It’s obviously a very serious type of cancer that needs to be caught in time, and it’s probably one that people are less likely to seek treatment for initially because of mainly embarrassment or have to have a colonoscopy. (Man, 40s) | |

| Ambiguity of risk | I think once you’ve had a transplant and you’ve got the reduced immunity, because you’re taking immunosuppressants, I think then you’ve probably got a greater chance. I suppose if you’re in poor health overall, then you’ve probably got a greater risk too, so if you’ve got, you know, the disease is well advanced, then your general health is not that wonderful, so therefore you’ve probably got a greater chance. (Man, 60s) |

| I didn’t recognize the correlation between kidney transplant and the prevalence of other cancers, other than melanoma. (Man, 40s) | |

| I don’t know why chronic kidney disease would make your bowels any more prone to cancer. I have no idea. Absolutely none. (Woman, 40s) | |

| Absence of symptomatic prompting | But until the symptoms appear, I suppose people like me just don’t think about it (Man, 60s) |

| If I’ve got pain or if I’ve got blood, anything like that. If I got to the doctor, and he says you’ve got signs of it. That’d become my number one priority, I’d have to do something about it then. But until then, I’ve got no signs or nothing yet. (Man, 50s) | |

| I’d probably wait for symptoms. I don’t know why. I spend enough time at the doctors as it is without going looking for other things. (Woman, 60s) | |

| Prioritizing kidney disease | |

| Preserving the chance of transplantation | I’d like to know that I’m healthy and that I could deserve it. (Man, 60s) |

| Then when I was doing the transplant workup, it became part of it, so I did it just to get it out of the way. Of course, when it came back negative, it was a peace of mind. (Man, 60s) | |

| I had the colonoscopy before the transplant to make sure I didn’t have bowel cancer, because it would be pointless doing it if I did. (Man, 50s) | |

| Over-riding attention to kidney disease | Bowel screening is at the bottom of my list really. Do you know what I mean? The top of my list is keeping well now, not in the future when I’m 60 or something. (Woman, 40s) |

| I’ve got other things to worry about. I mean, I may get something else, but when you’ve got kidneys and other things and that’s sort of down the bottom a little bit. (Woman, 60s) | |

| That includes exercise and maintain my fluid level and my—what I eat. So that’s a higher priority, only because it’s an everyday thing. It’s an everyday thing. It’s something that you have to do every day to have longevity or until you get a transplant at least. (Woman, 40s) | |

| Protecting graft survival | Having had a kidney transplant, you take every opportunity to make sure your own heath stays good, whether it’s looking after your skin, the mammogram, this, whatever, do it. (Man, 60s) |

| If something happens to me and that would stop me from having another transplant, and I’ve run through my whole family, I mean I don’t have another donor. (Man, 50s) | |

| As a transplant patient, I am obligated to test for cancer. (Man, 50s) | |

| Showing loyalty to the donor | If I ever forget, I’ve got the transplant donor to remind me. (Man, 60s) |

| I’ve got a gift from somebody that the words thank you were not enough, but I believe the best that I can do for the gift I’ve got is to go out and live the best life and look after it. (Woman, 40s) | |

| Preventing the crisis of cancer | |

| Evading severe consequences | Personally obviously, it gives me peace of mind knowing that I don’t have bowel cancer or if I do have cancer, that I can get some early treatment. (Man, 50s) |

| The best thing about that is I suppose you’re taking steps to take care of your health. (Woman, 40s) | |

| It’s better to know that you’ve got it or you haven’t got it to me. You have peace of mind. (Man, 60s) | |

| No one wants to die if early detection could save you, you know? If you want to live a bit longer, have the test done (Man, 50s) | |

| Cognizant of susceptibility | Finding out that I am susceptible to getting bowel cancer, so that’s always on my mind. (Man, 40s) |

| Knowing that renal transplant patients have a susceptibility to cancers, and so for that reason, I will take any cancer screening I can get. (Woman, 40s) | |

| If you able to have these tests, yeah I’m all for it. Prevention is better than getting into a terrible, terrible illness. (Man, 60s) | |

| Cognitive resistance | |

| Reluctance to perform a repulsive procedure | Only from personal feelings of—what would you call it—discomfort I suppose—distaste about the whole idea of basically dealing with feces. (Man, 50s) |

| The preparation was disgusting, most uncomfortable. (Woman, 70s) | |

| The worst thing with stool is collecting the samples. (Man, 60s) | |

| Intensifying disease burden threshold | I would imagine that people who are facing dialysis or transplant would have a fair degree of trepidation or hesitation, worry or concern about their illness—about their state of health. They may not want to know more bad news. If they had bad news at one time, they may not want—they might not be able to cope and handle one particular problem, but if they have a second but of problem that’s indirectly related to it, it might put an extra pressure on them they mightn’t want to face. (Man, 50s) |

| If people thought that, if it was picked up, that that’s the end, and it’s just one more thing they’re got to deal with, and it could kill them and may not actually want to deal with it. (Woman, 50s) | |

| I’ve got enough problems without worrying about that as well. (Woman 40s) | |

| Anxiety of a positive test | I was quite relieved when it came back negative. (Man, 40s) |

| Just the fear of the unknown. If I had to have one again, I’d be fine, but knowing, like anything to do with a medical procedure, there’s a certain amount of anxiety that wasn’t warranted. (Man, 40s) | |

| The procedure itself from what I understand is no real big drama. It’s just the fear of finding out. Yeah that’s a scary one. C is a bad work. But there’s only one way to alleviate those fears and that’s to find out. (Man, 50s) | |

| Accepting the inevitable | If it happens, [I’ll] deal with it then, [I’m] not worrying about if and when. It’s like anything in life. (Woman, 60s) |

| It’s not enough for me to stay up at night or anything; I just have to deal with whatever comes my way. (Man, 40s) | |

| No, I’m not going to be weighted down, shall we say, with something extra that I don’t have to worry about. I think that’s about right. It doesn’t cross my mind. (Woman, 70s) | |

| Pragmatic accessibility | |

| Negligible financial effect | Taking a bit of time off work, you weigh that up against the benefit. It’s always the cost-benefit thing. I feel very benefited by the whole thing and not inconvenienced in any way at all. (Man, 60s) |

| How does an individual put a monetary value on the peace of mind of having a bowel screening test? (Woman, 40s) | |

| From purely a financial point of view, it might cost them, I don’t know, $10 per sample or whatever, if they save some money from radical surgery and chemotherapy and the whole works. You just cannot from a purely financial point of view put a price on that. (Woman, 50s) | |

| Convenience | Well there’s no inconvenience, because it’s for the betterment of my health, so I didn’t see it as an inconvenience. (Woman, 60s) |

| I think it was convenient, because they didn’t put a time limit on it. They just said do it in your own time. I didn’t feel pressured or rushed into it. (Man, 40s) | |

| The inconvenience is even to participate, but that pales in comparison with benefits, so really it’s not an inconvenience; it’s only a very small inconvenience for much better rewards. I don’t know why people wouldn’t want to do it, I really don’t; to me, it’s an easy decision to make. It’s a win/win. (Man, 40s) | |

| Protecting anonymity | It was something that you did in the privacy of your own home, top back on, put away, and a drop place that you weren’t identified. (Man, 40s) |

| I think the thing that makes it a little bit more palatable is the fact that it’s in your own home, and you don't have to go anywhere, and it can be in the privacy of your bathroom, and you don’t have to be in front of anybody. Then, once you’ve got the sample sealed up in the bag, it doesn’t look like anything innocuous. I think that makes it a little bit more palatable for people. (Woman, 40s) | |

| I mean, I was in the privacy of my own home. It was a little bit uncomfortable, only because it’s not the norm—like it’s not usually what you do. (Woman, 40s) | |

| It was private, and it was one to one. No one had to know about what you did. (Woman, 40s) |

Figure 1.

Thematic schema. Decision making in patients regarding bowel cancer screening revolves around the overwhelming burden of their kidney disease, which is their main priority. Although patients with CKD acknowledge the importance of early detection to prevent further morbidity, the conflicting priorities, stigma, repulsion towards the screening process and anxiety of test outcome are ongoing barriers for participating in bowel cancer screening.

Invisibility of Cancer

Unspoken Stigma.

Bowel cancer and bowel cancer screening were described as a “taboo” topic. Some participants were reluctant to initiate discussion regarding bowel cancer, because they felt that speaking about bowel cancer made them feel as if their “privacy has been invaded.” Many felt that the topic was “too graphic,” and they would prefer to “bury their head in the sand” than to address the issue and talk about it with their family and friends. Although participants felt the cancer was “a very serious type,” the associated stigma meant that patients would be “less likely to seek treatment mainly because of embarrassment.” Some felt that that bowel cancer needed to be “talked about more” to increase the social acceptability of the topic.

Ambiguity of Risk.

Some transplant recipients understood that they had a “greater chance” of cancer because of immunosuppression use, although some thought that this increased risk was only for skin cancer. Some patients on dialysis and some patients with less advanced stage CKD “would not have dreamt” that bowel cancer was associated with kidney disease. Furthermore, some felt that they were “probably no worse” than the general population, because their health condition was “stabilized” with medications.

Absence of Symptomatic Prompting.

Participants were not prompted to “worry” about bowel cancer, because “until the symptoms appear, you just don’t think about it.” After symptoms, such as blood and pain, occur, then the issues would be their “number one priority”; until then, undergoing testing was not a priority, because they “spend enough time at the doctors as it is without going looking for other things.”

Prioritizing Kidney Disease

Preserving the Chance of Transplantation.

For participants who participated in bowel cancer screening as a part of their transplant assessment, the results of the screening gave them “peace of mind.” They became reassured that they were “healthy and they could deserve” the kidney when the opportunity for transplant arose, because it would be “devastating” to find out that they had cancer after receiving a transplant. Furthermore, they were particularly concerned that, if they then died due to the cancer, it was a “waste of someone else’s life, because [the other potential recipient] may die [due to not being transplanted].”

Over-Riding Attention to Kidney Disease.

Participants prioritized kidney disease as their main health concern, because “it’s an everyday thing.” Predialysis participants were focused on preventing progression to ESRD requiring dialysis—“you’re on dialysis for the rest of your life, you’re not thinking about cancer.” Transplant recipients strived to avoid “wasting the transplant” by “keeping well now, not in the future,” and some did not prioritize bowel cancer screening, because it was seen as a long-term preventative action. For participants who had completed bowel cancer screening, it did not “interest them that much at the moment,” because they had been reassured by their results and were able to focus on their kidney health, which was “very important at the moment.”

Protecting Graft Survival.

Kidney transplant recipients felt that it was important to be “proactive” and “take every opportunity” to make sure that they stay healthy and protect their transplant. One participant believed that it was important to maintain their health by undertaking preventative measures, such as bowel cancer screening, to ensure the longevity of their kidney, because they had “run out” of potential donors.

Showing Loyalty to the Donor.

Transplant recipients felt motivated to maintain their health out of a “responsibility to the donor” or as a way of “giving back.” One participant who received a kidney from his spouse believed that having “the donor to remind me” encouraged him to attend follow-up and tests, including bowel cancer screening.

Preventing the Crisis of Cancer

Evading Severe Consequences.

Performing a “quick test” for bowel cancer screening was worthwhile, because the results gave participants “peace of mind.” They felt reassured knowing that they could eliminate bowel cancer as a threat to their health, and it “relaxes the pressure on life.” Participants understood that, if you “get [bowel cancer] early enough, it’s treatable,” and you can “stop it getting any worse or killing you,” because “prevention is better than cure.” They also felt that it was worth taking the time to take a test, because it may “save a lot of pain and anguish” later on. Participants who had colonoscopies that detected polyps felt “happy” that they were now having regular checkups by gastroenterologists. Furthermore, participants were “accepting” of the possibility of having a false positive result, because it is “just part of the process.” They believed that proceeding with colonoscopy and being found to be normal after receiving a positive fecal immunochemical test result “is better than dying from cancer” and that “you need to know for sure” if there is anything serious.

Cognizant of Susceptibility.

Understanding the seriousness of the cancer and their heightened susceptibility was “all they needed to hear.” Patients who understood their heightened risk were motivated to participate in screening, and for many, they “jumped to the opportunity,” because “you can’t treat it lightly” and “prevention is better than getting a terrible, terrible illness.”

Cognitive Resistance

Reluctance to Perform a Repulsive Procedure.

Participants were reluctant to participate in bowel cancer screening due to the “horrendous” preparation of the colonoscopy and the fear of the “discomfort” of the test. They felt “embarrassed about [collecting a stool sample] more than anything,” and it was “distasteful performing the test.” For participants who had a colonoscopy, the preparation was the “uncomfortable” part, because it was “not very nice tasting” and “made a very messy business.” Some speculated that patients would “prefer to suffer the consequences [of bowel cancer] than take the test.”

Intensifying Disease Burden Threshold.

Participants commonly felt that screening for bowel cancer was “another thing to add to the list.” Already contending with multiple serious health issues, the thought of potentially being diagnosed with bowel cancer was perceived as another burden that would be too overwhelming with which to cope. Some were reluctant to participate, because they did “not want to know more bad news”: that would be “one more thing they’ve got to deal with,” and they have “enough problems without worrying” about bowel cancer as well.

Anxiety of a Positive Test.

Participants who completed the stool test or colonoscopy were “terrified” and “nervous” to find out the results. For many, it was “worrying at the time,” because they anticipated further burden on their life and risk to their survival. Some feared that they would “wake up with a colostomy bag” after the colonoscopy; however, they were “relieved” to find out that the results were normal.

Accepting the Inevitable.

Bowel cancer was “put on the backburner,” because participants had “other issues that are real.” They were willing to take a chance, and “if it happens, deal with it then,” because they did not want to be “weighted down” by a disease that had not yet occurred. Participants also felt that they “already had bad enough luck,” and they were hopeful that they would not suffer from any other health problems.

Pragmatic Accessibility

Negligible Financial Effect.

Costs to participate in screening (purchase of a fecal immunochemical test from the chemist and having time off work for the colonoscopy procedure) were not perceived as a major deterrent to screening. Bowel cancer screening was regarded as “hugely worthwhile,” and participants stated that, if the screening can be “lifesaving, then you can’t put a cost on that.” However, many participants believed that more patients with CKD may be more willing to complete the screening if it was free, because “cost-effectiveness is a priority” given their other health expenses. Participants who had proceeded with a colonoscopy after a positive fecal immunochemical test result felt that taking a bit of time off work was justified with the outcome of the colonoscopy result.

Convenience.

Before participating in the fecal immunochemical test, patients felt “apprehensive” toward the process but were reassured when they received “straightforward instructions” and the test was “less invasive” than having a colonoscopy. The “quick and easy” test was perceived as only a “small inconvenience for much better rewards,” acknowledging that the screening was integral for the “betterment of their health.”

Protecting Anonymity.

Participants felt that it was “more palatable” to complete their fecal immunochemical tests within the privacy of their own homes, because “no one had to know about what you did,” and they could not be identified. Although the test was considered out of the ordinary, the convenience of sending the test back in the mail (they could remain “anonymous,” and it did not “look like anything innocuous”) was applauded.

Decisions about bowel cancer screening were made in the context of managing what was perceived to be an overwhelming burden of kidney disease and maintaining and not disrupting the current health status. We did not identify any differences on the basis of age or burden of comorbidity. However, some differences were noted across CKD stages. Kidney transplant recipients, committed to preserving their graft, were particularly motivated to participate in cancer screening if it was perceived to prolong graft survival. In contrast, patients on dialysis had to contend with the daily, ongoing, and onerous dialysis regimen, and some felt that they did not have the physical and emotional capacity to participate in bowel cancer screening. A major barrier for predialysis patients and patients on dialysis was the fear of potential complications from a positive fecal immunochemical test result or a cancer diagnosis, because they are already overwhelmed with their current disease and its associated treatment burden.

Discussion

Patients with CKD understood the potential importance of early detection of bowel cancer through screening to potentially improve their overall survival, prevent serious morbidity, and maintain quality of life. However, CKD, in terms of both the disease and the treatment, was their predominant and over-riding health priority, and some patients relegated bowel cancer screening to be of more peripheral concern. Stigma, repulsion about the process of screening, and anxieties about the uncertain outcomes were additional barriers to participating in bowel cancer screening. Although recommendations around bowel cancer screening tend to be framed around prognosis, this did not seem to be a key focus or motivator for participants in our study.

Our findings reflect some common perspectives of other populations without CKD regarding decision making for bowel cancer screening. Barriers to bowel cancer screening, including lack of patient knowledge regarding risk factors and screening practices (18–22), unawareness that bowel cancer can be asymptomatic (22–24), fear of a positive result (22,25,26), time constraints, lack of knowledge on how to complete the test (25), and the perceived unpleasantness of the test (19), have been reported. In contrast, facilitators of bowel cancer screening identified in the general population include beliefs that screening is efficacious, safe, and able to provide “peace of mind” (22). However, our findings identify specific and unique concerns and priorities that underpin treatment decisions about cancer screening in patients with CKD as outlined above.

Our study has some potential limitations. Although participants from a diverse range of cultural backgrounds were included, non–English-speaking patients were excluded to avoid potential cultural and linguistic misinterpretation. Also, some interviews were conducted in the hospital, which may have inhibited open discussion. Although the study was conducted at three sites, the transferability of the findings to other settings is uncertain.

Patients with CKD articulated a number of priorities, values, and concerns about bowel cancer screening, which have key implications for shared decision making (27). This is of relevance, particularly because one of the recommendations put forward by the American Society of Nephrology under the Choosing Wisely Campaign states that routine cancer screening for patients on dialysis with life expectancies of <5 years does not improve survival and is not cost effective (5). Moreover, they suggest “an individualized approach to cancer screening incorporating patients’ health care goals and preferences, cancer risk factors, expected survival, and transplant status will improve the patient experience” (5). In view of this, patients in our study did not explicitly identify their expected survival as a consideration in their decisions about bowel cancer screening, and risk factors mentioned were limited to being on immunosuppression. Patients on dialysis did emphasis that they would be willing to participate in screening to protect their chance of receiving a kidney transplant. However, our study reiterates the need for a patient goal–orientated approach (28) that involves addressing the individual’s health goals and priorities. For patients with CKD, the kidney disease and treatment responsibilities related to kidney health may take higher priority than bowel cancer screening, which may be perceived as a potential pragmatic and psychosocial burden.

Guidance for clinicians and patients on how to achieve shared decision making in clinical practice is particularly limited for patients with complex comorbidities, because current tools, such as decision aids, are largely generic. We suggest the development of a communication rubric that incorporates the existing evidence of harms, barriers, facilitators, and patient preferences of screening in CKD to guide shared decision making. A better understanding of patients’ preferences is necessary to inform and support the development of policies to improve patient engagement and empowerment in decision making. Therefore, we suggest additional work to elicit tradeoffs using discrete choice experiments, which have been previously used in other areas of CKD (29), to assess what outcomes of screening are most valued by patients and their willingness to trade between the potential benefits and risks of screening. Additional research may be conducted with clinicians, who may also face decisional conflict around the issues as raised by the patients in the study.

Decision making for bowel cancer screening is complex in the CKD population. Although patients with CKD believed in the potential survival and health benefits of bowel cancer screening, the burden of CKD and treatment responsibilities are their immediate and prevailing priorities. The over-riding commitment to kidney-related needs can be a barrier given the additive burden and potential health consequences of bowel cancer screening; however, kidney transplant recipients may be more motivated to participate in cancer screening to preserve their graft survival. Addressing bowel cancer screening in the context of CKD, patients’ current health burdens, life priorities, and treatment goals can help to facilitate a patient-centered approach that may improve decisional satisfaction and screening outcomes in patients with CKD.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients who gave up their time to openly share their beliefs and experiences.

L.J.J. is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Program grant APP1092957. A.T. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (APP1106716).

The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10090916/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Birkeland SA, Løkkegaard H, Storm HH: Cancer risk in patients on dialysis and after renal transplantation. Lancet 355: 1886–1887, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stengel B: Chronic kidney disease and cancer: A troubling connection. J Nephrol 23: 253–262, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, van Leeuwen MT, Stewart JH, Law M, Chapman JR, Webster AC, Kaldor JM, Grulich AE: Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA 296: 2823–2831, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webster A, Wong G, Kelly PJ: Cancer. In: ANZDATA Registry Report 2012, edited by McDonald S, Clayton P, Hurst K, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2013, pp 10-1–10-10 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, Fink JC, Jaber BL, Linas SL, Michael B, O’Hare AM, Schaefer HM, Shaffer RN, Trachtman H, Weiner DE, Falk AR; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force : Critical and honest conversations: The evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1664–1672, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holley JL: Preventive medical screening is not appropriate for many chronic dialysis patients. Semin Dial 13: 369–371, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kajbaf S, Nichol G, Zimmerman D: Cancer screening and life expectancy of Canadian patients with kidney failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1786–1789, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBrun CJ, Diehl LF, Abbott KC, Welch PG, Yuan CM: Life expectancy benefits of cancer screening in the end-stage renal disease population. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 237–243, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiberd BA, Keough-Ryan T, Clase CM: Screening for prostate, breast and colorectal cancer in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 3: 619–625, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong G, Li MW, Howard K, Hua DK, Chapman JR, Bourke M, Turner R, Tong A, Craig JC: Health benefits and costs of screening for colorectal cancer in people on dialysis or who have received a kidney transplant. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 917–926, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong G, Howard K, Craig JC, Chapman JR: Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 85: 532–541, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong G, Howard K, Chapman JR, Tong A, Bourke MJ, Hayen A, Macaskill P, Hope RL, Williams N, Kieu A, Allen R, Chadban S, Pollock C, Webster A, Roger SD, Craig JC: Test performance of faecal occult blood testing for the detection of bowel cancer in people with chronic kidney disease (DETECT) protocol. BMC Public Health 11: 516, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong G, Chapman JR, Craig JC: Cancer screening in renal transplant recipients: What is the evidence? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3[Suppl 2]: S87–S100, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong G, Howard K, Chapman J, Pollock C, Chadban S, Salkeld G, Tong A, Williams N, Webster A, Craig JC: How do people with chronic kidney disease value cancer-related quality of life? Nephrology (Carlton) 17: 32–41, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong G, Howard K, Tong A, Craig JC: Cancer screening in people who have chronic disease: The example of kidney disease. Semin Dial 24: 72–78, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19: 349–357, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster AC, Craig JC, Simpson JM, Jones MP, Chapman JR: Identifying high risk groups and quantifying absolute risk of cancer after kidney transplantation: A cohort study of 15,183 recipients. Am J Transplant 7: 2140–2151, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beeker C, Kraft JM, Southwell BG, Jorgensen CM: Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: Qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. J Community Health 25: 263–278, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javanparast S, Ward PR, Carter SM, Wilson CJ: Barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in different population subgroups in Adelaide, South Australia. Med J Aust 196: 521–523, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo JH, Leong RW, Ching J, Yeoh K-G, Wu D-C, Murdani A, Cai Q, Chiu H-M, Chong VH, Rerknimitr R, Goh KL, Hilmi I, Byeon JS, Niaz SK, Siddique A, Wu KC, Matsuda T, Makharia G, Sollano J, Lee SK, Sung JJ; Asia Pacific Working Group in Colorectal Cancer : Knowledge of, attitudes toward, and barriers to participation of colorectal cancer screening tests in the Asia-Pacific region: A multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 76: 126–135, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J: Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med 39: 56–63, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Power E, Miles A, von Wagner C, Robb K, Wardle J: Uptake of colorectal cancer screening: System, provider and individual factors and strategies to improve participation. Future Oncol 5: 1371–1388, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Wijkerslooth TR, de Haan MC, Stoop EM, Deutekom M, Fockens P, Bossuyt PM, Thomeer M, van Ballegooijen M, Essink-Bot M-L, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ, Dekker E, Stoker J: Study protocol: Population screening for colorectal cancer by colonoscopy or CT colonography: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol 10: 47, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weitzman ER, Zapka J, Estabrook B, Goins KV: Risk and reluctance: Understanding impediments to colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med 32: 502–513, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christou A, Thompson SC: Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes and behavioural intention among Indigenous Western Australians. BMC Public Health 12: 528, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yusoff HM, Daud N, Noor NM, Rahim AA: Participation and barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13: 3983–3987, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH; Shared Decision-Making Workgroup of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force : Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention. A suggested approach from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med 26: 56–66, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM: Designing health care for the most common chronic condition--multimorbidity. JAMA 307: 2493–2494, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howell M, Wong G, Rose J, Tong A, Craig JC, Howard K: Eliciting patient preferences, priorities and trade-offs for outcomes following kidney transplantation: A pilot best-worst scaling survey. BMJ Open 6: e008163, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.