Abstract

Background and objectives

Two recent studies reported increased risk of ESRD after kidney donation. In both, the majority of ESRD was seen in those donating to a relative. Confounding this observation is that, in the absence of donation, relatives of those with ESRD are at increased risk for ESRD. Understanding the pathogenesis and risk factors for postdonation ESRD is critical for both donor selection and counseling.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We hypothesized that if familial relationship was an important consideration in pathogenesis, the donor and linked recipient would share ESRD etiology. We obtained information from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) on all living kidney donors subsequently waitlisted for a kidney transplant in the United States between January 1, 1996 and November 30, 2015, to determine (1) the donor–recipient relationship and (2) whether related donor–recipient pairs had similar causes of ESRD.

Results

We found that a significant amount of information, potentially available at the time of listing, was not reported to the OPTN. Of 441 kidney donors listed for transplant, only 169 had information allowing determination of interval from donation to listing, and only 99 (22% of the total) had information on the donor–recipient relationship and ESRD etiology. Of the 99 donors, 87 were related to their recipient. Strikingly, of the 87, only a minority (23%) of donor–recipient pairs shared ESRD etiology. Excluding hypertension, only 8% shared etiology.

Conclusions

A better understanding of ESRD in donors requires complete and detailed data collection, as well as a method to capture all ESRD end points. This study highlights the absence of critical information that is urgently needed to provide a meaningful understanding of ESRD after kidney donation. We found that of living related donors listed for transplant, where both donor and recipient cause of ESRD is recorded, only a minority share ESRD etiology with their recipient.

Keywords: Outcomes; living; kidney; donation; transplant; live kidney donor; ESRD; Counseling; Donor Selection; Humans; hypertension; Kidney Failure, Chronic; kidney transplantation; risk factors; Tissue Donors; Tissue and Organ Procurement; United States

Introduction

Long-term studies comparing live kidney donors with age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched general population controls have found no increased risk of ESRD for donors (1–5). In contrast, two studies comparing donors with selected, healthy matched controls found that although the absolute risk of developing ESRD postdonation remained low, the relative risk in donors versus controls increased 3- to 11-fold (6,7). In each study, the actual number of donors with ESRD was small: nine of 1901 in the first (6) and 99 of 96,217 in the second (7). In each, the majority of ESRD occurred in those donating to a relative: all nine (100%) in the first and 83 of 99 (84%) in the second. Of note, however, in the absence of donation, relatives of individuals with ESRD have increased ESRD risk (8–14).

These findings are difficult to assimilate into an understanding of donor risk that can be defined and communicated to donor candidates, particularly given the small numbers of donors with ESRD in each study. Understanding the pathogenesis of ESRD after donation would facilitate both donor candidate selection and better education to promote informed consent. For example, if increased risk is mainly limited to those with a family history of ESRD, then those without ESRD in their families could be counseled differently as they consider donation. Postdonation ESRD might be caused by nephrectomy-imposed reduction in GFR followed by the fall in GFR associated with aging, new-onset kidney disease, or new-onset systemic disease (e.g., diabetes, congestive heart failure, or hypertension) affecting kidney function.

We hypothesized that because of shared biology and/or environmental factors, related donors who subsequently developed ESRD would have the same cause of ESRD as their recipients. To better understand the role of familial risk in donors who had been listed for transplant, and to determine whether the donor and recipient shared the same primary disease, we obtained information on United States kidney donors listed for kidney transplantation with the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

In the United States, there is no formal mechanism to track long-term donor outcomes. The United Network for Organ Sharing, a nonprofit organization funded via a grant from the US Department of Health and Human Services, administers the OPTN, which in turn functions as a quasi-regulatory body to manage the national transplant waitlist and the database for all organ transplants performed in the United States (including information about all live organ donors) (15). Kidney donors’ outcomes are tracked by the OPTN for 2 years after donation, a relatively recent requirement for transplant centers. Before 1996, when a patient with ESRD was listed with the OPTN for a transplant, there was no requirement for a transplant center to identify the patient as a past kidney donor; in 1996, the OPTN began giving waitlist priority points for past donors, a change that increased the likelihood that past donors on the waitlist would be identified as such.

Materials and Methods

For this study, we included all donors known to have developed ESRD after donation, and who were listed with the OPTN from January 1, 1996 to November 30, 2015 (irrespective of when they donated). We requested information on date of donation, age at donation, date of listing, age at listing, interval between donation and listing, ethnicity, sex, donor–recipient relationship (first-degree relative [parent, child, or sibling], other relative, or unrelated), and primary cause of donor and recipient ESRD. For comparison, we also requested the characteristics of all living donors reported to the OPTN as of November 30, 2015.

We studied interval from donation to transplant, donor–recipient relationship, time from donation to ESRD, and whether related donor–recipient pairs shared a common cause of ESRD. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD and categorical variables as a percent. The paired t test and chi-squared test were used to compare these variables. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of Donors Listed for Transplant

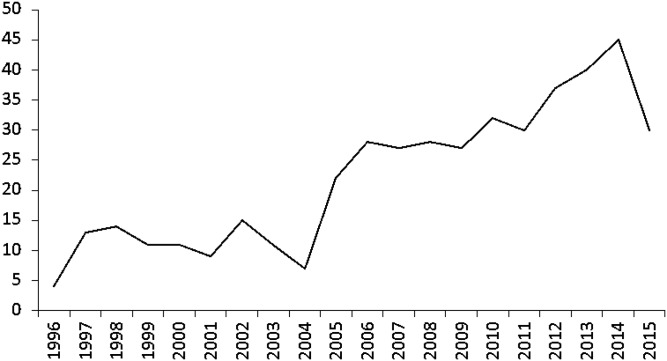

Between January 1, 1996 and November 30, 2015, a total of 441 kidney donors who developed ESRD were listed for a kidney transplant with the OPTN. The number listed each year increased up until 2014 (Figure 1). Of the 441, 60% were men. The median age at listing was 54 years (interquartile range [IQR], 46–62). Table 1 shows the percent listed for ages 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥65 years. By ethnicity, 46% were white, 39% were black, 10% were Hispanic, and 6% were other.

Figure 1.

Entire cohort of 441: number of donors listed for a kidney transplant, by year of listing.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the entire cohort of donors listed with the OPTN between January 1, 1996 and November 30, 2015 (n=441) and the subset with information on donor–recipient relationship and recipient cause of disease (n=99)

| Characteristics | Entire Cohort (n=441) | Subset (n=99) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at listing, yr | 54 | 48 |

| % listed when 18–34a | 5 | 11 |

| % listed when 35–49 | 29 | 47 |

| % listed when 50–64 | 47 | 34 |

| % listed when ≥65 | 19 | 7 |

| Ethnicity, % | ||

| White | 46 | 38 |

| Black | 39 | 43 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 14 |

| Other | 6 | 4 |

| Most common causes of ESRD, %b | ||

| Hypertension | 32 | 35 |

| Other | 18 | 15 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 17 | 7 |

| FSGS | 12 | 10 |

OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

Between groups, P<0.001.

Between groups, P=0.002.

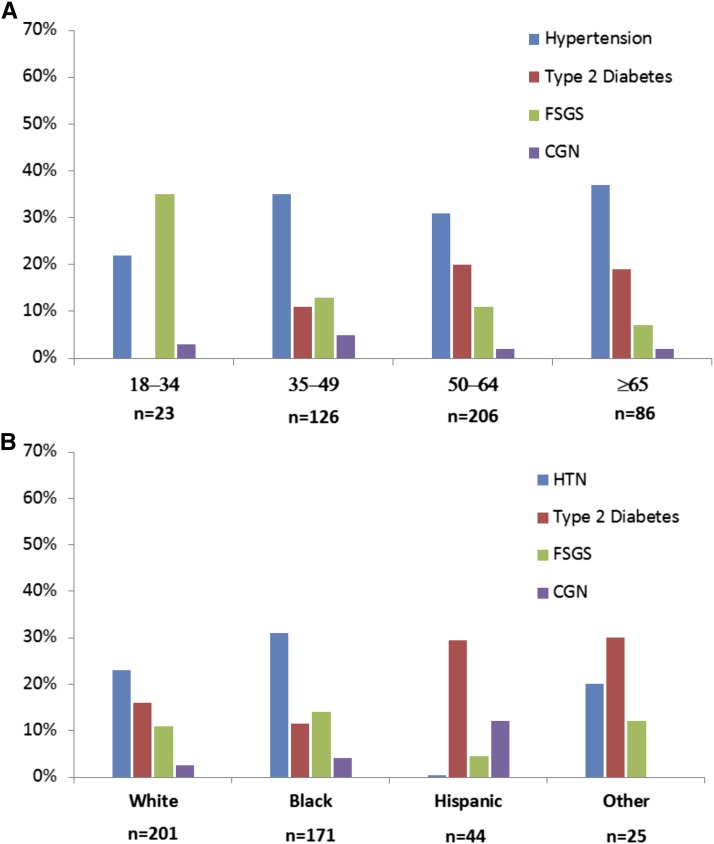

The four most frequently reported causes of ESRD, accounting for 79% of the total, were hypertension (32%), other (18%), type 2 diabetes (17%), and FSGS (12%) (Table 1). Less common diagnoses are shown in Table 2. Those listed at a younger age were more likely to have ESRD attributed to FSGS or hypertension (Figure 2A). With increasing age at listing, hypertension and diabetes accounted for most of the causes. Hypertension was the most common cause of ESRD in whites and blacks, whereas diabetes was the most common in Hispanics and others (Figure 2B).

Table 2.

Less common etiologies of ESRD in donors listed for transplant

| Cause of ESRD | n |

|---|---|

| Glomerular disease (n=60) | |

| Chronic GN (unspecified) | 20 |

| IgA nephropathy | 9 |

| Membranous GN | 5 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 5 |

| Chronic glomerulosclerosis (unspecified) | 4 |

| Familial nephropathy | 4 |

| Alport syndrome | 3 |

| Postinfectious GN | 2 |

| Amyloidosis | 2 |

| Nephronophthisis | 1 |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | 1 |

| Thin basement membrane | 1 |

| Scleroderma | 1 |

| Sarcoidosis | 1 |

| HIV nephropathy | 1 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 9 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 4 |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 3 |

| Analgesic nephropathy | 2 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 1 |

| Fabry disease | 1 |

| Acute tubular necrosis | 1 |

| Vasculitis | 1 |

| Acquired obstructive nephropathy | 1 |

| Nephrolithiasis | 1 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 1 |

Figure 2.

Entire cohort of 441: primary cause of ESRD by age at listing and ethnicity. (A) Age at listing. B) Ethnicity. CGN, chronic GN; HTN, hypertension.

Age at Donation and Listing, and Interval from Donation to Listing

Of the 441 donors listed for transplant, only 169 (38%) had information available on age at donation and interval from donation to listing. For this subset, the median age at donation was 34 (IQR, 27–41) years; at listing, 49 (IQR, 43–58) years. The median time from donation to listing was 14 (IQR, 10–19) years. The age at donation in relation to the interval from donation to listing is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subset of 169 donors with age at donation listed: interval from donation to listing by age at donation

| Years from Donation to Listing | Age at Donation, yr | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 (n=93), n(%) | 35–49 (n=59), n(%) | ≥50 (n=17), n(%) | |

| 0–4 | 5 (5) | 5 (8) | 0 |

| 5–9 | 19 (20) | 10 (17) | 5 (29) |

| 10–14 | 25 (27) | 18 (31) | 9 (53) |

| 15–19 | 21 (23) | 14 (24) | 2 (12) |

| ≥20 | 23 (25) | 12 (20) | 1 (6) |

Alarmingly, ten donors (6%) were listed within 4 years of donation, and an additional 34 (20%) were listed within 5–9 years. Glomerular disease accounted for the majority of those listed within 10 years of donation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cause of ESRD for 44 donors listed within 10 yr of donation

| Cause | n |

|---|---|

| Glomerular disease (n=20) | |

| FSGS | 11 |

| Chronic GN | 4 |

| Membranous nephropathy | 2 |

| IgA nephropathy | 1 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 |

| Postinfectious crescentic GN | 1 |

| Hypertension | 7 |

| Chronic pyelonephritis | 2 |

| Chronic nephrosclerosis | 1 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1 |

| Other | 13 |

Relationship to Recipient

Of the 169 donors with information on age at donation and interval from donation to listing, only 99 had information included on donor and recipient ethnicity, donor–recipient relationship, and recipient primary disease. The majority of missing information was for those donating before 1994.

This subset (n=99) differed from the entire cohort listed with the OPTN (n=441) in age at listing (P<0.001) (Table 1). For example, in the subset of 99, 58% were listed before age 50 years (34% for the total cohort) (Table 1). In addition, the two cohorts differed in the frequency of the four most common causes of ESRD (P=0.002).

Of the 99 donors with information on donor and recipient cause of disease, 82 (83%) were first-degree relatives, five (5%) were other relatives, and 12 (12%) were unrelated. Of the 87 donors related to their recipient, only 20 (23%) had a similar primary cause of ESRD. Of these 87 related donors, 35 had hypertension as the primary cause of ESRD, and of these, 16 (46%) donated to a recipient with hypertension. Of seven donors with type 2 diabetes as the primary cause of ESRD, only two (29%) donated to a recipient with the same diagnosis; for other diseases, only two of 45 (4%) shared diagnoses (FSGS and Alport syndrome).

Discussion

We identified a considerably higher number (n=441) of living kidney donors listed for transplant than have been reported in previous studies (7,16–19). This is likely, in part, because we included a (slightly) longer time span for this study. Over time, a growing number of kidney donors have been listed for transplant, with an increasing rate in recent years (Figure 1). It is unknown if this trend is because (1) in the first years of the OPTN database, there was inconsistent reporting and/or lack of true donor follow-up; (2) an increasing number of donors are currently receiving follow-up care, making diagnosis more likely; (3) an increasing number of donors are now >20 years postdonation; and/or (4) changing practices in donor selection have led to an increased risk of ESRD postdonation.

We found that for the majority of waitlisted donors, a significant amount of information readily available at the time of their transplant listing was missing. Schold et al. (20) have previously noted the significant amount of donor follow-up information not reported to the OPTN within the first 2 years postdonation. In this study, those listed most recently did have more complete information on date and age at donation, interval from donation to listing, and donor–recipient relationship. Muzaale et al. (7) have previously reported that those donating more recently had more complete data, but still had a great deal of missing information that would have been available at the time of listing, such as BP, smoking status, body mass index, renal function, education level, and relationship to the recipient (Table 5).

Table 5.

Percent of missing information at the time of donation for 96,217 donors listed with the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) between April 1, 1994 and November 30, 2011 [adapted from Muzaale et al. (7)]

| First Available in OPTN Data | % Missing Data | |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine level | After 1997 | Between 1998 and 2001, 34% missing |

| Between 2002 and 2005, 5% missing | ||

| After 2006, 1% missing | ||

| Smoking status | After 2004 | Between 2005 and 2009, 5% missing |

| Between 2010 and 2011, 1% missing | ||

| BP | After 1999 | Between 2000 and 2004, 24% missing |

| Between 2005 and 2009, 8% missing | ||

| Between 2010 and 2011, 4% missing | ||

| Body mass index | After 2003 | Between 2005 and 2009, 33% missing |

| Between 2010 and 2011, 19% missing | ||

| Education | After 1998 | Between 2000 and 2004, 42% missing |

| Between 2005 and 2009, 21% missing | ||

| Between 2010 and 2011, 9% missing | ||

| Relationship to recipient | — | Between 1991 and 2011, 0.25% missing |

—, not presented.

The missing information limits development of an understanding of reasons and risk factors for ESRD after donation. For example, in the OPTN database, there is detailed information on only those both donating and developing ESRD since June of 1994. For these, the mean time from donation to ESRD was 14 years (IQR, 10–19 years). However, it is likely that for the entire donor population (including those donating before 1994), the mean time to ESRD was longer. For donors at the University of Minnesota who subsequently developed ESRD (n=36), the mean (±SD) time from donation to ESRD was 27.4±9.5 years (median, 30 years [unpublished data, H Ibrahim and A Matas]). Similarly, a survey of Canadian transplant centers showed a mean (n=16) time from donation to ESRD of 27.5±7.01 years (range, 14–39 years) (personal communication from J. Lesage and J. Gill).

Even with the information available, there are concerns about the donors’ listed etiology of ESRD and the time from donation to ESRD. First, a number of donors with ESRD have listed etiology due to diseases with a known genetic mode of transmission. There were three cases attributed to Alport syndrome, four attributed to familial nephropathy, one to Fabry disease, and one to polycystic kidney disease. These are potentially avoidable. Second, almost 20% of donors have causes of ESRD listed as “other” (Table 1). Given the extensive choices available for documenting the causes of kidney disease, “other” likely means unknown. Although it is not entirely uncommon for etiology of ESRD to be unknown, we believe it is critical, to better understand donor risk and to be better able to inform future donor candidates, to do all due diligence to determine the etiology of donor ESRD. Third, it is concerning that of those with known interval from donation to listing (n=169), 6% were listed <5 years postdonation and 26% were listed <10 years postdonation. Certainly, a donor candidate evaluation cannot rule out future disease; however, the relatively high percent of ESRD that developed within 10 years after donation emphasizes the importance of detailed and thorough donor candidate screening.

Of the 99 donors listed for transplant whose relationship to the recipient was known, 87 (87%) were related; in contrast, 63% of all living donors reported to the OPTN (as of November 30, 2015) donated to a relative. Our study cohort represents a slightly different, but generally overlapping, time period from the OPTN data. Surprisingly, for these related donors with ESRD, there was little similarity between donor and recipient cause of ESRD. The only exception was hypertension: nearly half of donors who had hypertension as the primary cause of ESRD had donated to a relative whose ESRD was also attributed to hypertension. Given that a kidney biopsy is rarely done when a patient with ESRD presents with hypertension, the association seen with hypertension is not robust (21). However, only 6.5% of donors with other causes of ESRD had donated to a relative with the same primary disease. In support of this observation, an informal survey of transplant centers worldwide identified 51 donors who had donated to a relative and subsequently developed ESRD. Of these, only four donor–recipient pairs (8%) were known to have a similar disease (A.J. Matas, unpublished observations).

For the 441 donors with ESRD reported to the OPTN database, there is a wide range in age at donation (18 to >70 years old) and a wide range in numerous other characteristics, with varying intervals from donation to ESRD and many different ESRD etiologies. Given the information available, we can only make approximations as to the pathogenesis of ESRD after donation. Even if the OPTN database were complete, we would emphasize that an accurate analysis of donor ESRD (and any potential links to recipient ESRD causes) should tally all donors with ESRD regardless of treatment modality (transplant, dialysis, and no treatment), ideally including those without access to care and those who donated in the United States but live overseas. Because these harder-to-reach donors may also be more vulnerable (poorer and more geographically remote), their outcomes are particularly relevant in order to understand and discuss the risk of developing ESRD postdonation (22). Although some of this information can be obtained by combining searches from other databases, the ideal solution is the establishment of a national donor database (23).

Fortunately, ESRD is a relatively rare event after kidney donation. However, when we as clinicians counsel donor candidates, it is important to have a better understanding of the long-term risk of ESRD (or any other sentinel event) postdonation, along with any associated risk factors. Per the available data, donors who developed ESRD were usually related to their recipient but did not seem to share ESRD etiology with the recipient, so many questions remain. A mechanism to systematically track donor outcomes—a donor database—is warranted. Donors deserve it.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the help of Eric Beeson at the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, who provided the initial data and kindly addressed all of our follow-up questions. We thank Mary Knatterud for editorial assistance, and Hang McLaughlin and Stephanie Taylor for assistance preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services number 234-2005-37011C.

The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Nordén G, Lennerling A, Rizell M, Mjörnstedt L, Wramner L, Olausson M: Incidence of end-stage renal disease among live kidney donors. Transplantation 82: 1646–1648, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, Gross CR, Matas AJ: Long-term consequences of kidney donation. N Engl J Med 360: 459–469, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto M, Akioka K, Nobori S, Ushigome H, Kozaki K, Kaihara S, Yoshimura N: Short- and long-term donor outcomes after kidney donation: Analysis of 601 cases over a 35-year period at Japanese single center. Transplantation 87: 419–423, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mjøen G, Reisaeter A, Hallan S, Line PD, Hartmann A, Midtvedt K, Foss A, Dahle DO, Holdaas H: Overall and cardiovascular mortality in Norwegian kidney donors compared to the background population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 443–447, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier C, Pallet N, Cherqaoui Z, Pucheu S, Kreis H, Méjean A, Timsit MO, Landais P, Legendre C: Very long-term follow-up of living kidney donors. Transpl Int 25: 385–390, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, Foss A, Midtvedt K, Øyen O, Reisæter A, Pfeffer P, Jenssen T, Leivestad T, Line PD, Øvrehus M, Dale DO, Pihlstrøm H, Holme I, Dekker FW, Holdaas H: Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 86: 162–167, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, Montgomery RA, McBride MA, Wainright JL, Segev DL: Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA 311: 579–586, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman BI, Tuttle AB, Spray BJ: Familial predisposition to nephropathy in African-Americans with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 710–713, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson R, Grim CE, Opgenorth TJ: A familial risk of chronic renal failure among blacks on dialysis? J Clin Epidemiol 41: 1189–1196, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman BI, Spray BJ, Tuttle AB, Buckalew VM Jr: The familial risk of end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Am J Kidney Dis 21: 387–393, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei HH, Perneger TV, Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Coresh J: Familial aggregation of renal disease in a population-based case-control study. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1270–1276, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergman S, Key BO, Kirk KA, Warnock DG, Rostant SG: Kidney disease in the first-degree relatives of African-Americans with hypertensive end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 341–346, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Dea DF, Murphy SW, Hefferton D, Parfrey PS: Higher risk for renal failure in first-degree relatives of white patients with end-stage renal disease: A population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis 32: 794–801, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skrunes R, Svarstad E, Reisæter AV, Vikse BE: Familial clustering of ESRD in the Norwegian population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1692–1700, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Home page of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Available at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov. Accessed November 15, 2016

- 16.Ross LF: Living kidney donors and ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 23–27, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potluri V, Harhay MN, Wilson FP, Bloom RD, Reese PP: Kidney transplant outcomes for prior living organ donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1188–1194, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anjum S, Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Bae S, Luo X, Grams ME, Lentine KL, Garg AX, Segev DL: Patterns of end-stage renal disease caused by diabetes, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis in live kidney donors [published online ahead of print June 11, 2016]. Am J Transplant doi:10.1111/ajt.13917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Anjum S, Liao C, Garg AX, Lentine KL, Segev DL: Recipient outcomes following transplantation of allografts from live kidney donors who subsequently developed end-stage renal disease [published online ahead of print May 12, 2016]. Am J Transplant doi:10.1111/ajt.13869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schold JD, Buccini LD, Rodrigue JR, Mandelbrot D, Goldfarb DA, Flechner SM, Kayler LK, Poggio ED: Critical factors associated with missing follow-up data for living kidney donors in the United States. Am J Transplant 15: 2394–2403, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlessinger SD, Tankersley MR, Curtis JJ: Clinical documentation of end-stage renal disease due to hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis 23: 655–660, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Luo X, Kumar K, Brown RS, Anjum S, Montgomery RA, Lentine KL, Segev DL: Outcomes of live kidney donors who develop end-stage renal disease. Transplantation 100: 1306–1312, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, Charlton M, Cohen D, Confer D, Cooper M, Danovitch G, Davis C, Delmonico F, Dew MA, Garvey C, Gaston R, Gill J, Gillespie B, Ibrahim H, Jacobs C, Kahn J, Kasiske B, Kim J, Lentine K, Manyalich M, Medina-Pestana J, Merion R, Moxey-Mims M, Odim J, Opelz G, Orlowski J, Rizvi A, Roberts J, Segev D, Sledge T, Steiner R, Taler S, Textor S, Thiel G, Waterman A, Williams E, Wolfe R, Wynn J, Matas AJ; Living Kidney Donor Follow-Up Conference Writing Group : Living kidney donor follow-up: State-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant 11: 2561–2568, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]