Abstract

The enteric nervous system (ENS) of jawed vertebrates arises primarily from vagal neural crest cells that migrate to the foregut and subsequently colonize and innervate the entire gastrointestinal tract. To gain insight into its evolutionary origin, we examined ENS development in the basal jawless vertebrate, the sea lamprey. Surprisingly, we found no evidence for the existence of a vagally-derived enteric neural crest population in the lamprey. Rather, DiI labeling showed that late-migrating cells, originating from the trunk neural tube and associated with nerve fibers, differentiated into neurons within the gut wall and typhlosole. We propose that these trunk-derived neural crest cells are homologous to Schwann cell precursors (SCPs), recently shown in mammalian embryos to populate post-embryonic parasympathetic ganglia1,2, including enteric ganglia3. Our results suggest that neural crest-derived SCPs made an important contribution to the ancient ENS of early jawless vertebrates, a role that was largely subsumed by vagal neural crest cells in early gnathostomes.

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is comprised of thousands of interconnected ganglia embedded within the wall of the gut4,5, making it the most complex portion of the peripheral nervous system in amniotes. The ENS of jawed vertebrates innervates the entire gastrointestinal tract to regulate muscle contraction, chemosensation, water balance, and gut secretion6. Classical transplantation experiments have demonstrated that the neurons and glia of the gut are largely derived from the “vagal” population of neural crest cells that arise within the post-otic portion of the hindbrain7,8. They subsequently migrate to the foregut and embark upon the longest migration of any embryonic cell type, from foregut to hindgut.

The sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus, is a jawless (agnathan) vertebrate and an experimentally tractable representative of the cyclostomes. As the sister group to jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes), lamprey are an important model for identifying traits common throughout vertebrates. Lamprey possess migrating neural crest cells that give rise to many cell types, including melanocytes, cartilage, sensory neurons and glia, but lack other neural crest-derived structures that are present in gnathostomes like jaws and sympathetic chain ganglia9,10. Given that lamprey embryos lack sympathetic ganglia, we sought to examine other components of the autonomic nervous system, with a focus on the ENS. Adult lamprey have a simple ENS that includes ganglionated plexuses of serotonin (5-HT) producing cells, as well as a smaller number of catecholamine-containing neurons11,12. However, the developmental origin of these enteric neurons is unknown.

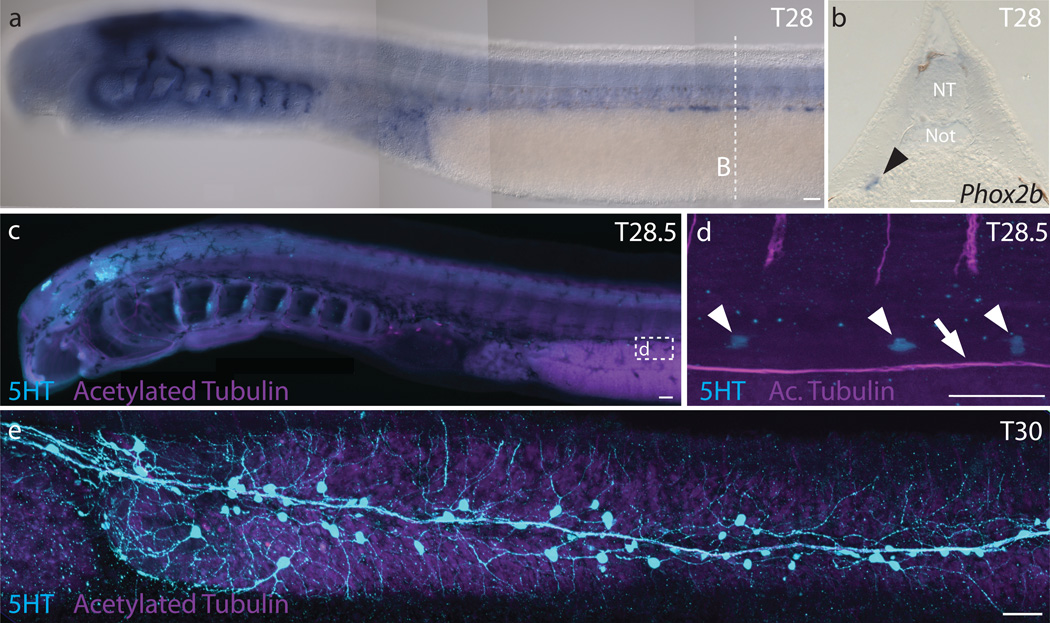

As a first step in analysis of lamprey ENS development, we examined the time course of neuronal appearance along the developing embryonic gut by performing in situ hybridization for Phox2b, which is expressed in enteric neurons in many jawed vertebrates9. Expression of lamprey Phox2b is detectable along the gut from early stages (Tahara Stage 25 [T25]9), and by stage T28 or embryonic day (E) 20, Phox2b expressing cells are associated with a depression in the gut that will become the typhlosole, an hematopoietic tissue associated with elements of the ENS (Fig. 1a–b). Using a 5-HT antibody, serotonin-immunoreactive neurons were first observed within the gut wall at ~T28.5 (Fig. 1c–d) in the anterior trunk region. With time, the numbers increased, and 5-HT+ neurons were noted progressively posteriorly, with particularly high cell numbers in the cloacal region, as reported previously13. By T30 (E30), there are >100 neurons along the gut in association with the typhlosole and vagus nerve (Fig. 1e; Extended Data Fig. 1). Interestingly, individual serotonergic neuroblasts also were often associated with axon bundles emanating ventrally from the dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 2f; Extended Data Fig. 1a). In addition to 5-HT+ neurons, we also noted 5-HT+ columnar cells that may represent gut enterochromaffin cells (Extended Data Fig. 1a–b).

Figure 1. Early formation of enteric neurons in the lamprey P. marinus.

a, Phox2b expression in dorsolateral cells of a T28 embryo. b, Transverse cross-section of a T28 embryo shows Phox2b expression in the depression of the typhlosole (black arrowhead). c, 5-HT and acetylated tubulin immunoreactivity in a slightly older T28.5 embryo. d, 5-HT is detectable in neurons (white arrowheads) adjacent to the vagus nerve (white arrow). e, Serotonergic neurons form small ganglia within the enteric plexus of a T30 embryo. NT: neural tube; Not: notochord. Scale bar indicates 50 um.

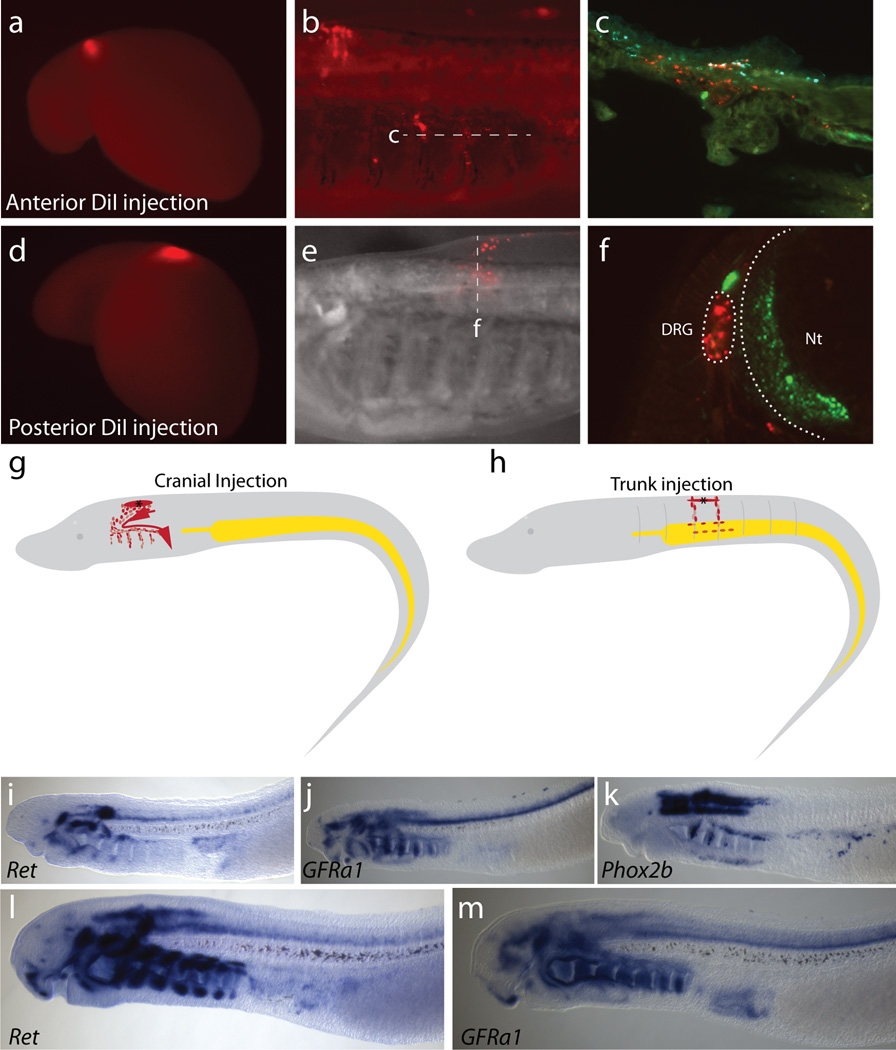

Figure 2. DiI labeled cells in the neural tube contribute to enteric ganglia.

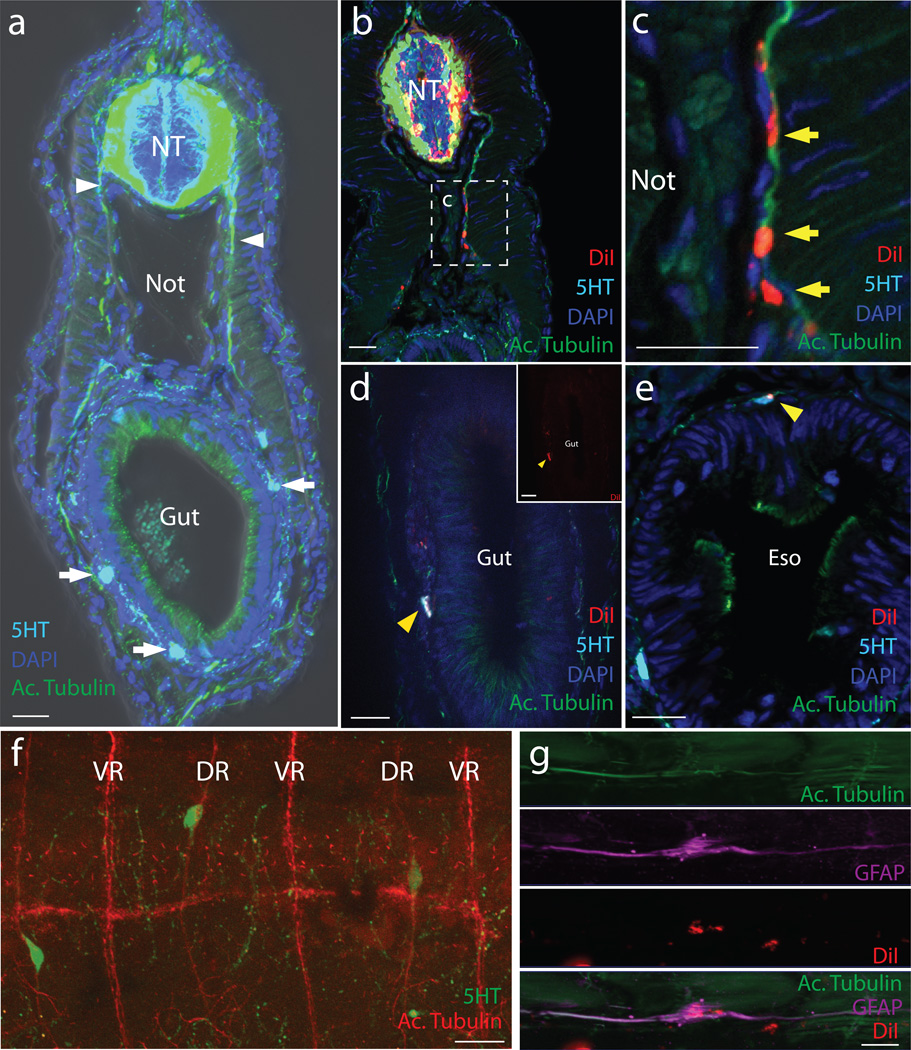

Immunohistochemistry of T30 lamprey transverse cryosections. a, Uninjected control highlighting neuronal projections (white arrowhead) and serotonergic neurons (white arrows) around the gut. Green:Acetylated tubulin; Blue:DAPI; Cyan:5-HT. b–d, DiI injected “tubefill” embryos. Red:DiI; Green:Acetylated Tubulin; Cyan:5HT; Blue:DAPI. b & c, DiI within the neural tube, dorsal root ganglia and along axon bundles. d, A DiI-labeled enteric neuron (acetylated tubulin+, 5-HT+) within the gut wall typhlosole (white arrowhead). Inset shows DiI only. e, A DiI-labeled neuron (acetylated tubulin+, 5HT+) in the esophagus (yellow arrowhead). See cell counts in Table 1. f, 5-HT+ cells along dorsal root (DR) nerve processes but not ventral roots (VR). g, A DiI-labelled GFAP-positive cell associated with the lateral line. Eso: esophagus; NT: neural tube; Not: notochord. Scale bar indicates 20 um.

We next sought to determine the embryological origin of the neurons in the gut by performing lineage labeling with the lipophilic dye DiI14. In chicken, vagal neural crest cells that contribute to the ENS arise from the hindbrain neural tube adjacent to somites 1–77. After exiting the neural tube, they migrate ventrally, invade the foregut, and undergo a collective cell migration along the rostrocaudal extent of the gut. To test whether lamprey possess a homologous cell population, we performed focal injections of DiI into the dorsal portion of the caudal hindbrain (corresponding to the site of origin of vagal neural crest in gnathostomes) of T20 (E6) embryos. Regardless of the exact injection site, dye labeled cells spread within the hindbrain and emigrated from the neural tube as a stream directly above the pharynx (Extended Data Fig. 2). From this site, they progressed ventrally, then turned caudally to populate all of the branchial arches (Extended Data Fig. 2), similar to previously reported migration patterns of cranial neural crest cells15,16. However, despite many focal injections (n=46) into the caudal hindbrain homologous to “vagal”, we failed to find evidence of DiI-labeled cells in the gut. We next looked for expression of the vagal neural crest marker, ret, in lamprey, since it is required for vagal neural crest development in gnathostomes17–19. To this end, we cloned a lamprey ret homolog and the ret co-receptor GFRα1 and examined their expression patterns by in situ hybridization. The results show lamprey ret and GFRα1 are expressed in many parts of the embryo, including the typhlosole. Ret and GFRα1 expression are first observed in a region anterior to the gut at T26 (Extended Data Fig. 2i–j) in a manner reminiscent of Phox2b expression (Extended Data Fig. 2k). However, we did not observe expression in neural crest cells migrating from caudal hindbrain, raising the intriguing possibility that enteric neurons might arise from a different cellular source.

In gnathostomes, migrating trunk neural crest cells fail to invade the immediately underlying gut due to the presence of repulsive signals like Slit that block their entry20. Recently, however, a secondary contribution to the mammalian ENS has been uncovered that comes not from vagal neural crest but rather from trunk neural crest-derived Schwann cell precursors (SCPs) associated with extrinsic nerves that contribute post-natally to calretinin-containing neurons of the gut3. Using Dhh-cre mice to lineage trace immature Schwann cells, Uesaka and colleagues found that ~15% of enteric neurons in mice were derived from trunk SCPs. Intriguingly, this population persists in ret null mice3. To examine the possibility that a homologous population may exist in lamprey, we asked whether cells emerging from the trunk neural tube might contribute to neurons of the gut. To test this, we performed focal DiI injections into the dorsal trunk neural tube as well as neural tube lumen injections following its cavitation at T22-T23 (~E8), thus labeling the entire neural tube as well as presumptive neural crest cells prior to their emigration. Both labeling techniques yielded similar results. By T25 (E14), such injections label neural crest-derived cells in dorsal root ganglia and mesenchyme cells of the fin9. Interestingly, at later stages, we observed DiI-labeled cell bodies closely associated with nerve processes, recognized by acetylated tubulin staining above the gut (n=47 embryos) (Fig. 2a–c). These individual DiI-labeled cells were visible as early as T28 (E18–20) and persisted until the latest stages examined, T30 (E30-E35), by which time the yolk is reduced, facilitating imaging. In the trunk of lamprey, there are two nerve roots per trunk segment—a dorsal root that contains fibers emanating from neural crest-derived dorsal root ganglia and a ventral root that contains motor neuron nerve fibers. Interestingly, DiI labeled cells were associated with these dorsal roots (Fig. 2c). Similarly, serotonergic neuroblasts were selectively associated with and appeared to migrate only along these dorsal root bundles (Fig. 2d), consistent with a neural crest origin.

To establish whether the DiI-labeled cells differentiated into enteric neurons, embryos were sectioned and stained with antibodies to serotonin and acetylated tubulin as a mature neuronal marker. The results, based on examination of transverse sections through 25 representative embryos at T30 (E30–35) in which we quantitated cells that were both acetylated tubulin and serotonin-positive, are summarized in Table 1. We noted numerous DiI-labeled serotonergic neurons (DiI/5HT/acetylated tubulin-positive cells) in the anterior gut (Fig. 2d), esophagus (Fig. 2e), typhlosole, and adjacent tissues, as well as other DiI+ neurons that were serotonin negative (Extended Data Fig. 1c). These results demonstrate that neural crest cells originating from the trunk neural tube can contribute to enteric neuron populations within the gut wall.

Table 1.

Number of DiI-labeled neurons (AcTub+) in 25 representative E30–35 embryos in which DiI had been injected into the neural tube.

| Location | DiI+, 5HT+ | DiI+, 5HT− | Total DiI-labeled Neurons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagus | 22 | 2 | 24 |

| Intestine (Basal Typhlosole) | 26 | 0 | 26 |

| Intestine (Typhlosole mesenchyme) | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Total | 52 | 7 | 59 |

To determine if markers associated with neural crest-derived SCPs were present in the lamprey trunk, we stained embryos with an antibody to GFAP, which labels glial and Schwann cells in amniotes. We observed prominent GFAP+ cells in lamprey embryos including some that were DiI positive along the lateral line (Fig. 2g), consistent with the possibility that neural crest cells give rise to the nonmyelinating Schwann cells of lampreys21.

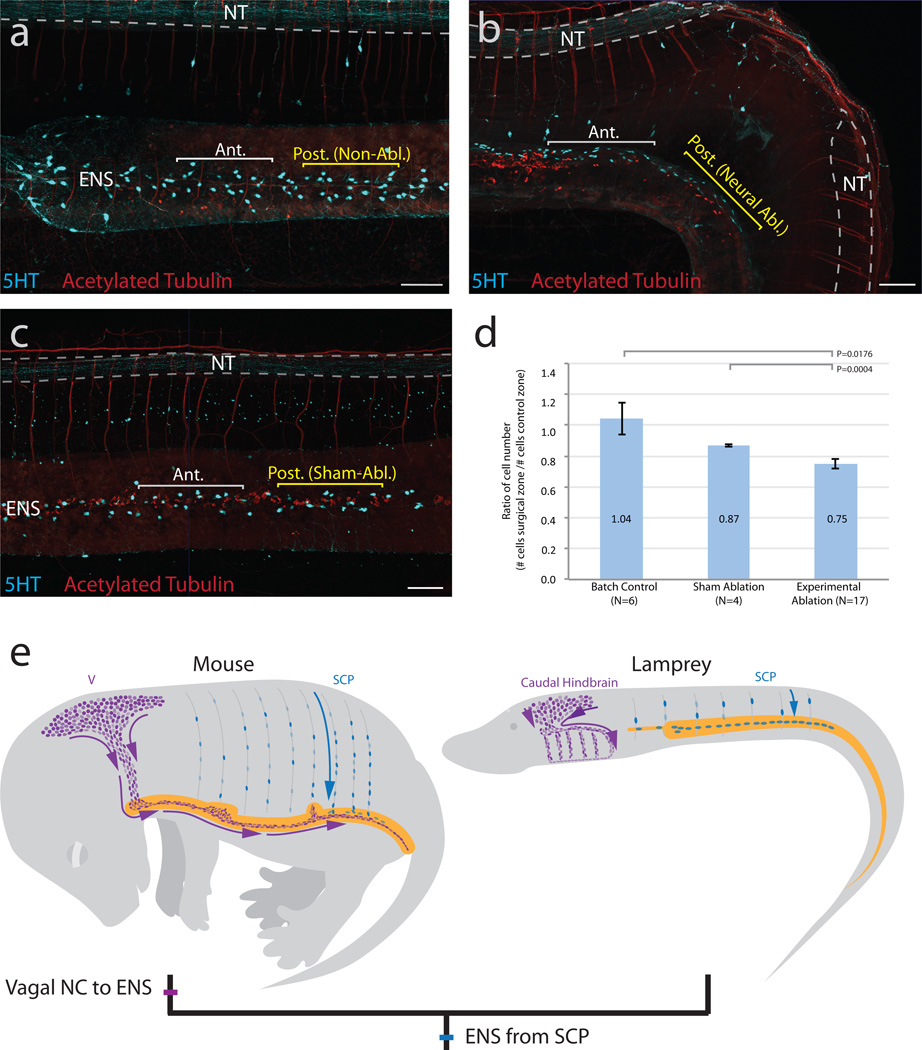

Finally, as an additional means of testing whether enteric neurons originate from within the trunk neural tube, we performed neural tube ablation (n=17), a method classically used to demonstrate the neural crest origin of enteric neurons8,22, at approximately T24. To accommodate slight natural variation in the number of ENS neurons between embryos, we expressed counts as the ratio of serotonergic cells in the zone adjacent to the ablation versus an identically sized region spaced approximately one somite length to the anterior. In comparison to control nonablated (n=6) or sham-ablated (n=4) embryos (Fig. 3a,c), experimental embryos show a significant decrease in the ratio of ENS serotonergic cells (Fig. 3b,d). We noted an ~12% decrease of serotonergic neurons in the ablated region compared with sham-ablated embryos and an ~25% decrease relative to stage controls, consistent with a model of ENS neuronal precursors migrating from trunk NC-derived cells. This decrease was particularly surprising given the remarkable regenerative capacity of the lamprey spinal cord23,24.

Figure 3. Neural tube ablation disrupts ENS development.

a–c, Whole-mount images of T30 lamprey embryos (Red:HuC/D and acetylated tubulin; Cyan:5HT). a, Control nonablated embryo. b, Ablation of the neural tube at T24 results in a decrease of serotonergic (5HT+) cells in the adjacent gut relative to an equivalently sized anterior region. c, A sham-ablated embryo, in which epidermis and neural tube were cut but not removed, does not show a reduction of cells. d, Ablated embryos show a significantly lower ratio of serotonergic cells (# cells in surgical zone/# cells in anterior zone) than sham-ablated controls (Ttest; P=0.0004) and non-ablated batch controls (Ttest, P=0.0176). Error bars indicate s.e.m. e, Schematic model of neural crest contributions to the ENS in mouse compared with lamprey. Vagal neural crest (V; purple); Schwann cell precursors (SCP; blue); Lamprey branchial crest (BC; purple). Scale bar indicates 100 um.

Recent evidence suggests that many neural crest derivatives in post-natal mammals, including skin and peripheral ganglia, arise from SCPs that are closely associated with extrinsic innervation to these structures. For example, SCPs along nerve processes differentiate into melanocytes of the skin and parasympathetic ganglia1,2,25. Moreover, SCPs that migrate along trunk spinal nerves contribute to a subpopulation of enteric neurons in mice3. These studies prove the existence of neural crest-derived cells that contribute to the peripheral nervous system and other derivatives at post-embryonic stages. Our results suggest that these trunk neural crest-derived cell types may represent an ancient and evolutionary conserved source of cells that contribute to the ENS. Moreover, our data suggest that agnathans might lack a classical “vagal” neural crest, leading us to speculate that a vagal neural crest population with ability to form enteric neurons arose in stem gnathostomes (Fig. 3e). We cannot rule out contributions from other sources, but focus here on the positive contribution of trunk neural crest-derived cells to enteric neurons. Although we cannot formally exclude the possibility that the mechanisms for populating the ENS arose independently in agnathans and gnathostomes, we favor the idea that the contribution of SCPs to the ENS might represent a primitive (plesiomorphic) state retained from early vertebrates, and perhaps common to all living vertebrates. With emergence of jawed vertebrates, new traits, including jaws, sympathetic ganglia, and vagal neural crest-derived enteric ganglia, appeared under the umbrella of embryonic neural crest derivatives.

Methods

Adult sea lamprey (P. marinus) were supplied by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Dept. of the Interior, and cultured according to previous protocols26 in compliance with California Institute of Technology IACUC protocol #1436. Embryo batches with less than 70% survival were excluded from analyses, and all experimental embryos were randomly chosen from appropriately staged cultures. Celltracker CM-DiI (Thermo Scientific) was resuspended as described9, and surgical ablations were performed using forceps and tungsten needles. For surgeries, only embryos with ablations of 2–6 somite lengths, adjacent to anterior intestine, and without damage to other tissues were included in analyses. Serotonergic neurons associated with the typhlosole were counted in a 200–300 um region adjacent to the ablation site, and an equivalently sized nonablated region beginning approximately one myotome length anterior to the ablation. Measurements were taken in sibling non-ablated embryos and sham-ablated embryos in which ectoderm and neural tissue was cut, but not removed, at similar axial locations. Investigators were not blinded to group allocations. Probes for Phox2, GFRα1, and ret were cloned from cDNA with primers for Ensembl gene models ENSPMAG00000008433, ENSPMAT00000009324, and ENSPMAT00000008763. In situ hybridizations and antibody stainings were performed using previously described protocols27,28. Anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma clone 6-11b-1, #T7541; Mouse IgG2b) and anti-5-HT (Immunostar #20080, Rabbit IgG) were used at 1:500. Anti-GFAP (Dako, #Z0334; Rabbit IgG) was used at 1:400. Embryos were processed for cryosectioning according to standard protocols, and were sectioned on a Microm HM550 cryostat. Microscopy was performed on a Zeiss AxioImager.M2 equipped with an Apotome.2. Images were cropped, rotated, and resized using Adobe Photoshop CC and image panels were constructed using Adobe Illustrator CC. Statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel.

Extended Data

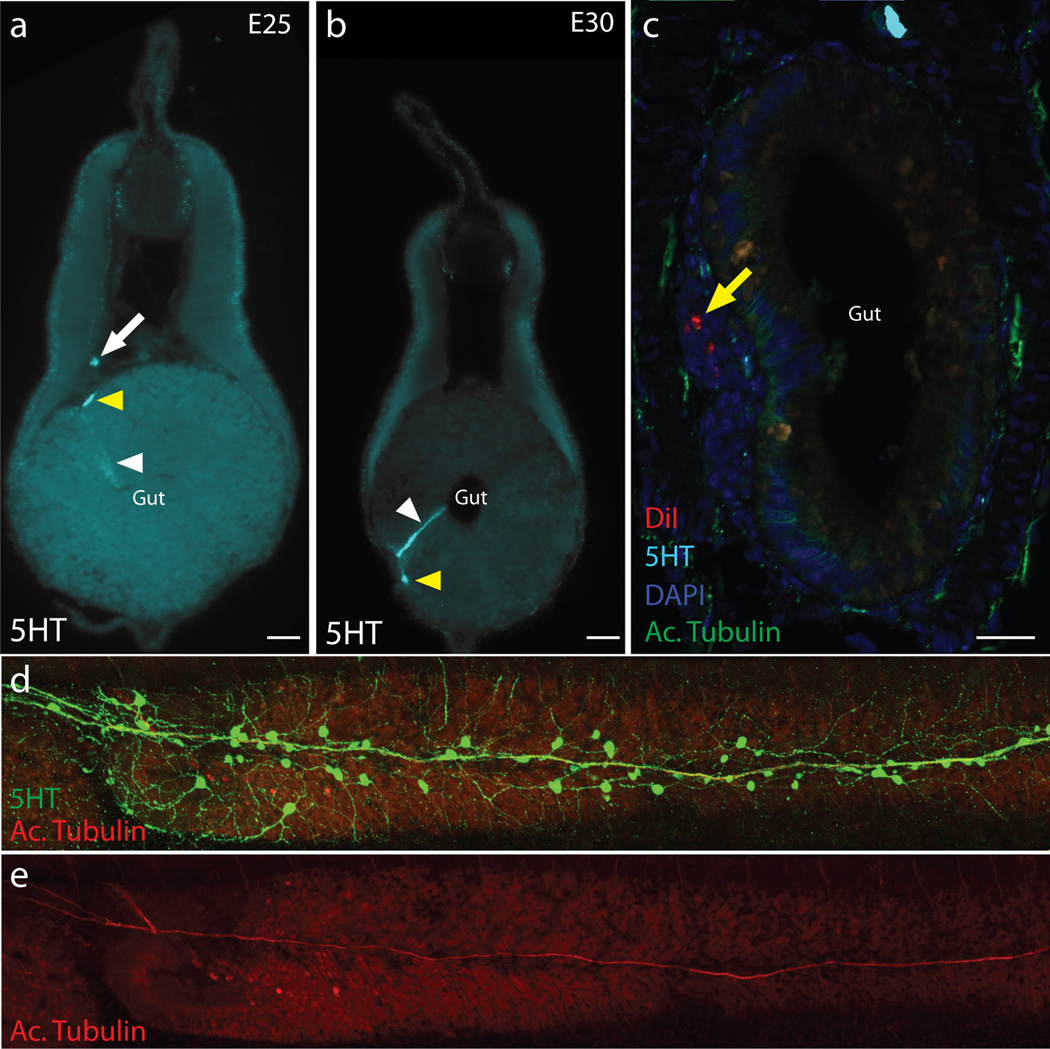

Extended Data Figure 1. 5HT immunoreactive cells in the gut, and DiI labelling.

a–b, 5-HT immunoreactivity in embryonic day (E) 25 (a) and E30 (b) embryos. Serotonergic neurons (yellow arrowheads) are positioned within the typhlosole, near the endodermal mucosa. A cell present in the columnar epithelium (white arrowhead) might represent an endocrine (enterochromaffin) cell. Cells positioned dorsal to the typhlosole might be neuroblasts (white arrow). c, DiI labeling results in labeled cells (yellow arrowhead) originating from the neural tube, migrating to the gut and typhlosole. Red:DiI; Cyan:5HT; Blue:DAPI; Green:Acet. Tubulin. d, Serotonergic (Green: 5-HT; Red: Acet. Tubulin) neurons in a T30 embryo, and e, Acetylated Tubulin staining alone shows the position of the vagus nerve.

Extended Data Figure 2. DiI labeling of the caudal hindbrain population shows contributions to the branchial arches.

a–c & e–f, Sample time lapse imaging of two separate DiI-labeled embryos around the hindbrain level. a & d, Initial injection at E6-E6.5 (T20). b, Final DiI localization of embryo in A, 10 days post injection (E16). c, Frontal cryosection through the branchial basket shows DiI along the branchial arches. Red: DiI, Green: Neurofilament-M, Cyan: Collagen type II. e, Final DiI localization of embryo in A 14 days post-injection (E20). f, Transverse section through the lamprey branchial basket shows DiI within the DRG. Red: DiI; Green: Neurofilament-M. g–h, Schematic depiction of individual injection sites for cranial (g) and trunk (h) injections. i–m, Genes associated with gnathostome enteric neurons, Ret (i, l), GFRalpha1 (j, m), and Phox2b (k) do not appear to be coexpressed at T26 (i–k) and T27 (l–m), prior to enteric neuron differentiation in lamprey. DRG:dorsal root ganglia; Nt: neural tube.

Acknowledgments

We thank Clare Baker, Michael Piacentino, and Laura Kerosuo for discussion as well as Megan Martik and Marcos Simoes-Costa for their comments on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Project was conceived by MB, and analyses were designed by SG and MB. Descriptive analyses of enteric neurons were performed by SG. Cranial DiI labeling was performed by BU, MB, and SG. Trunk DiI labeling was performed by BU, SG, and MB. Surgeries were performed, imaged, and analyzed by SG and BU. Schematics were drawn by SG. Manuscript was written by MB, SG, and BU.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References Cited

- 1.Espinosa-Medina I, et al. Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic ganglia derive from Schwann cell precursors. Science. 2014;345:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1253286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyachuk V, et al. Neurodevelopment. Parasympathetic neurons originate from nerve-associated peripheral glial progenitors. Science. 2014;345:82–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1253281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uesaka T, Nagashimada M, Enomoto H. Neuronal differentiation in Schwann cell lineage underlies postnatal neurogenesis in the enteric nervous system. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:9879–9888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1239-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibbins I. In: Comparative Physiology and Evolution of the Autonomic Nervous System. Nilsson S, Holmgren S, editors. Vol. 4. Harwood Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lake JI, Heuckeroth RO. Enteric nervous system development: migration, differentiation, and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G1–G24. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00452.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furness JB, Costa M. The enteric nervous system. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Douarin NM, Teillet MA. The migration of neural crest cells to the wall of the digestive tract in avian embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1973;30:31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yntema, Hammond WS. The origin of intrinsic ganglia of trunk viscera from vagal neural crest in the chick embryo. J. Comp. Neurol. 1954;101:515–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.901010212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Häming D, et al. Expression of sympathetic nervous system genes in Lamprey suggests their recruitment for specification of a new vertebrate feature. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnels AG. On the development and morphology of the skeleton of the head of Petromyzon. Acta Zool. 1948;29:139–279. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgarten HG, Björklund A, Lachenmayer L. Evidence for the existence of serotonin-, dopamine-, and noradrenaline-containing neurons in the gut of Lampetra fluviatilis. Z Zellforsch. 1973;141:33–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00307395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yui R, Nagata Y, Fujita T. Immunocytochemical studies on the islet and the gut of the arctic lamprey, Lampetra japonica. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 1988;51:109–119. doi: 10.1679/aohc.51.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakao T, Ishizawa A. An electron microscopic study of autonomic nerve cells in the cloacal region of the lamprey, Lampetra japonica. J. Neurocytol. 1982;11:517–532. doi: 10.1007/BF01262422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serbedzija GN, Bronner-Fraser M, Fraser SE. A vital dye analysis of the timing and pathways of avian trunk neural crest cell migration. Development (Cambridge, England) 1989;106:809–816. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCauley DW, Bronner-Fraser M. Neural crest contributions to the lamprey head. Development (Cambridge, England) 2003;130:2317–2327. doi: 10.1242/dev.00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horigome N, et al. Development of cephalic neural crest cells in embryos of Lampetra japonica, with special reference to the evolution of the jaw. Developmental Biology. 1999;207:287–308. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pachnis V, Mankoo B, Costantini F. Expression of the c-ret proto-oncogene during mouse embryogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 1993;119:1005–1017. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcos-Gutiérrez CV, Wilson SW, Holder N, Pachnis V. The zebrafish homologue of the ret receptor and its pattern of expression during embryogenesis. Oncogene. 1997;14:879–889. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Natarajan D, Marcos-Gutierrez C, Pachnis V, de Graaff E. Requirement of signalling by receptor tyrosine kinase RET for the directed migration of enteric nervous system progenitor cells during mammalian embryogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2002;129:5151–5160. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bellard ME, Rao Y, Bronner-Fraser M. Dual function of Slit2 in repulsion and enhanced migration of trunk, but not vagal, neural crest cells. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters A. The structure of the peripheral nerves of the lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis) Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1960;4:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(60)80027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones DS. The origin of the vagi and the parasympathetic ganglion cells of the viscera of the chick. Anat. Rec. 1942 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovainen CM. Regeneration of Müller and Mauthner axons after spinal transection in larval lampreys. J. Comp. Neurol. 1976;168:545–554. doi: 10.1002/cne.901680407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selzer ME. Mechanisms of functional recovery and regeneration after spinal cord transection in larval sea lamprey. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1978;277:395–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adameyko I, et al. Schwann cell precursors from nerve innervation are a cellular origin of melanocytes in skin. Cell. 2009;139:366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikitina N, Bronner-Fraser M, Sauka-Spengler T. Culturing lamprey embryos. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2009 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauka-Spengler T, Meulemans D, Jones M, Bronner-Fraser M. Ancient evolutionary origin of the neural crest gene regulatory network. Devel Cell. 2007;13:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikitina N, Bronner-Fraser M, Sauka-Spengler T. Immunostaining of whole-mount and sectioned lamprey embryos. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2009 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]