Abstract

Psychotherapeutic genetic counseling is an increasingly relevant practice description. In this paper we aim to demonstrate how psychotherapeutic genetic counseling can be achieved by using psychological theories to guide one’s approach to working with clients. We describe two illustrative examples, fuzzy trace theory and cognitive behavior theory, and apply them to two challenging cases. The theories were partially derived from evidence of beneficial client outcomes using a psychotherapeutic approach to patient care in other settings. We aim to demonstrate how these two specific theories can inform psychotherapeutic genetic counseling practice, and use them as examples of how to take a psychological theory and effectively apply it to genetic counseling.

Keywords: Psychotherapeutic genetic counseling, Genetic counseling, Fuzzy trace theory, Shared decision making, Cognitive behavior therapy

Introduction

Austin and colleagues have argued that genetic counseling falls under the umbrella of psychotherapies broadly defined (Austin et al. 2014). Psychotherapy is: “the informed and intentional application of clinical methods and interpersonal stances derived from established psychological principles for the purpose of assisting people to modify their behaviors, cognitions, emotions, and/or other personal characteristics in directions that the participants deem desirable” (Zeig and Munion 1990). This describes genetic counseling. The NSGC definition of genetic counseling as the process of “helping people understand and adapt to the medical, psychological, and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease” is absolutely compatible with this definition of psychotherapy (Kessler 1979; Resta et al. 2006).

Yet imposter syndrome is common in the profession–genetic counselors do not all feel that they are up to the task. Genetic counselors may feel uncomfortable identifying their practice as falling under the umbrella of psychotherapy, perhaps due to perceptions that their training in this domain was insufficient to justify this alignment. Yet the Accreditation Council of Genetic Counseling (ACGC) practice-based competencies include: employing active listening and interviewing skills to identify, assess, and empathically respond to stated and emerging concerns, using a range of genetic counseling skills and models to facilitate informed decision-making and adaptation to genetic risks or conditions, and promoting client-centered, informed, non-coercive and value-based decision making (Accreditation Council of Genetic Counseling 2015). Core genetic counseling skills are psychotherapeutically oriented. Genetic counselors can own the moniker of “psychotherapeutic” genetic counseling.

Why is it important to conceptualize genetic counseling as a type of psychotherapy? One reason is that there is evidence to guide psychotherapeutic practice. For example, encouraging patients to articulate their feelings, offering empathic responses, and avoiding verbal dominance by the provider result in higher levels of satisfaction, improved affective outcomes, and better cognitive (knowledge-based) outcomes (Edwards et al. 2008; Ellington et al. 2011; Meiser et al. 2008). Avoiding verbal dominance in genetic counseling sessions invites client contributions to the session to share prior experience, knowledge, values and beliefs related to the indication for the consultation. Another reason is that decades of research on the effectiveness of psychotherapy across theories identifies relational elements as central to positive client outcomes (Horvath and Symonds 1991). The therapeutic alliance, mutual engagement and interaction, is more important than what theory a therapist ascribes to or what interventions she favors.

Genetic counselors have positioned the client-counselor relationship and client affective responses at the core of their practice as diagramed in the reciprocal engagement model (Veach et al. 2007). Even for genetic counselors that view their roles to be genetics educators, evidence suggests that enhanced knowledge or understanding may best be achieved using a psychotherapeutic approach (Edwards et al. 2008; Ellington et al. 2011; Meiser et al. 2008). Adult learning is most effective when it is experiential, meaning adults relate new information to what we know. To achieve understanding of new information, counselors need to appreciate clients’ relevant prior experiences. This may be best achieved by forming a therapeutic alliance to engage in a psychotherapeutic approach that facilitates assessment of ideas, values and beliefs that contribute to current understanding and form the basis for acquiring new information in the context of the relationship.

Conceptualizing genetic counseling as psychotherapy also allows genetic counselors to draw on the wealth of theory and evidence from psychology and social science. In this paper we explore how theoretical frameworks and empiric evidence can guide aspects of psychotherapeutic genetic counseling. Among a number of decision and psychotherapeutic theories, we chose two that emerged directly from our clinical work and hold promise for genetic counseling. We describe the fuzzy trace theory and how it can direct genetic counselors in facilitating decisions and explore use of a cognitive behavioral orientation in genetic counseling. In presenting these two theories, we are not suggesting that these are the only theories relevant to genetic counseling practice, but rather exemplars to model the use of psychotherapeutic theories in this context.

In the desire to help people integrate, process and use information in a way that helps them and their families, the key role of genetics presides. In choosing a psychotherapeutic approach the counselor need not do so at the expense of genetic information. The integration of both is essential to what constitutes genetic counseling (Kessler 1997).

Decision Science

Decision science can be applied to guide the process and outcomes of health-related decision making. Facilitating decision making, such as whether to undergo genetic testing, is a prominent component of genetic counseling. It appears in the ACGC practice-based competencies, NSGC practice guidelines and in the definition of genetic counseling (Accreditation Council of Genetic Counseling 2015; National Society of Genetic Counselors; Resta et al. 2006). Decision theories can inform facilitation of decision making by genetic counselors within a psychotherapeutic approach.

Genetic counselors strive for clients to make informed choices that are in keeping with their values and beliefs (Michie et al. 2002). An informed choice has been defined as one that is based on sufficient knowledge and consistent with one’s attitudes toward the object of the decision; one’s attitudes are shaped by values and beliefs. This model is consistent with decision science that has shown that decision making is not exclusively the product of rational thought (Ariely 2010). Rather rational thinking is intertwined with feelings, personalities and the context of the decisions that leads to a bounded rationality (Gigerenzer and Selten 2001). Gain-loss experiments demonstrate that there are commonalities among how people make decisions and we can often predict their choices. For example, people are more averse to losing something of value that they have than failing to gain something of the same value (Kahneman and Tversky 1984). Knowledge of this human tendency allows counselors to consider whether they are offering clients choices as potential losses or gains. As genetic counselors are in the business of framing choices for their clients, they function as choice architects. Thaler and Sunstein (2008) convey the key role choice architects have in framing how choices about health are offered in their book, Nudge. They cite evidence to support the inference that the way genetic counselors offer choices to clients may generate unintended contributions to the outcome. Evidence for this comes from an experimental study of panel testing with different numbers of genes that showed test selection varied according to the number of genes on the panel (Barr 2015).

Fuzzy Trace Theory

Fuzzy trace is a decision making theory with direct application to genetic counseling. It is a dual processing theory centered on two mental processes involved in making decisions: gist and verbatim (Reyna 2008). Gist traces are fuzzy representations of an event (e.g., its bottom-line meaning). Verbatim traces are detailed representations. Evidence reveals that people often reason using gist traces rather than verbatim when making decisions (Reyna 2008). Even when clients understand probabilities their choice will often be governed by the bottom-line meaning of the information (e.g. a perception that “the risk is high” or “the risk is low”; “the outcome is bad” or “the outcome is good”) rather than the actual risk (Austin et al. 2012). A study of the role of gist traces about breast cancer risk revealed its prominence as a key factor in decisional outcomes (Lloyd et al. 2001). As such, genetics practicing a psychotherapeutic approach to decision making may opt to facilitate clients’ use of bottom line meaning or gist of the information over actual risk perception when the client can articulate the gist of the information and it’s relevance to the decision. Applying fuzzy trace theory to genetic counseling, it follows that clients can make informed decisions based on gist that they feel confident about and are less likely to regret.

In genetic counseling, clients’ decisions may be preference-based or medically recommended. Preference-based decisions are made in the absence of evidence that one choice is significantly better than another and when those choices are based on values and beliefs. They differ from medically recommended decisions where there is evidence of clinical benefit in following a course of action such as screening for women who have a pathogenic variant in BRCA1. If they follow clinical guidelines they reduce their mortality from cancer. Preference-based decisions are prominently guided by values and beliefs. The classic examples of preference-based decisions in genetic counseling are in the prenatal setting. In prenatal genetic counselors aim to promote client-centered decisions. Decisions whether to act on a recommended course of action are complicated as they can involve multiple steps (such as undergoing recurrent screening).

Shared decision making is a collaborative deliberation used to help people make both types of decisions (Elwyn et al. 2014). Shared decision making describes the cooperation between clients and health care providers to consider alternative courses of action, where alternatives are explicit and well understood, and clients are supported to consider their personal and relational preferences (Elwyn et al. 2014). Three essential elements to shared decision making are curiosity, respect and empathy. Together these elements constitute a working alliance, a relational element found to be key in predicting positive outcomes in psychotherapy (Horvath and Symonds 1991). Genetic counselors’ professional curiosity about their clients stimulates them to engage in learning what clients are thinking, while conveying deep respect and empathic concern about the situation in which they are making a decision. Shared decision making recognizes relevant and alternative courses of action, suggesting clients need to be aware of and know what will happen if they do not follow each option. This strategy for engagement capitalizes on the therapeutic alliance to compare alternative courses of actions and their consequences and elicit preferences for a specific course of action, contextualizing a psychotherapeutic counseling approach. The strategy of engaging in shared decision making in genetic counseling (Elwyn et al. 2000; Sivell et al. 2008) is particularly relevant to incorporating theories of decision making such as fuzzy trace theory.

In addition to a theoretical framework (ie., fuzzy trace theory), practice model (ie., reciprocal engagement) and decision strategy (ie., shared decision making) the personal resources of our clients and the context for making a decision matter. Cognitive and emotional load significantly affect decision making. Cognitive load may result from striving to understand risk information. “Numeracy” describes our comfort and ability to manipulate numbers (Peters et al. 2007; Portnoy et al. 2010). Many people have low numeracy skills. Genetic counselors may assume that providing risk information in several different ways and illustrating the numbers are sufficient for people to understand and use the information. For clients with low numeracy skills and those who do not think in terms of abstract probabilities, this may not be achieved (Reyna et al. 2009). Gist of a health risk may dominate decision making in these circumstances. Similarly with literacy, the ability to understand spoken and written language, clients may not be able to extract useful meaning from hearing genetic information. People who may be generally literate can simultaneously have low health literacy skills or genetic literacy skills (Erby et al. 2008; Roter et al. 2009). Evidence shows that genetic counselors use complex terms during genetic counseling sessions that may challenge the accessibility of information to clients (Ashtiani et al. 2014; Roter et al. 2009). Use of less complex language and scientific jargon may help clients to learn new information and put it to use.

In the health context, the most challenging circumstances under which to make a decision are when it is life altering, there is little time to make it and the decision is emotionally burdensome. Therefore, genetic counselors in the prenatal context facilitate the hardest types of decisions. Immediately emotional decisions, such as whether to continue a pregnancy when the fetus is affected with a condition, may more often result in decisions guided by emotions at the expense of understanding. For example, the emotional burden of learning abnormal results may lead parents to choose termination as a subconscious effort to move beyond excruciating circumstances rather than as the outcome of a carefully deliberated decision that weighs potential harms and benefits to the child and their family. Using a psychotherapeutic approach, genetic counselors can help couples acknowledge and manage the emotional burden and strive to articulate their values and beliefs that are critical to the decision at hand. As such, a psychotherapeutic counseling approach to pre-test prenatal sessions should include clients’ anticipation of the low probability that their fetus is affected in the context of less psychological stress and time pressure. Laying the groundwork for consideration of the clients’ values and beliefs can be of critical importance to having to make downstream decisions under duress within a short interval for the few patients who will face a decision whether to continue a pregnancy.

Case Example: Fuzzy Trace Theory

Susan is a 52 year-old woman who learned upon her mother’s recent death that genetic testing revealed a pathogenic variation in TDP-43, posthumously diagnosing her with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Frontotemporal Dementia (ALS/FTD) proteinopathy. Susan is at 50 % risk for this neurodegenerative condition that can manifest as either or both conditions and for which there are limited treatments and no cure. She sought genetic counseling to discuss preference-based predictive testing.

The genetic counselor began by asking Susan to relate the story of learning of her mother’s diagnosis and her own risk to establish the backdrop for a working alliance. Susan described how unexpected the information was given that her mother had carried a long-standing diagnosis of bipolar disorder and the recent onset of her ALS symptoms. In relating the history, Susan conveyed her clear understanding of the characteristics of the condition and the risk.

In processing the information, Susan expressed a strong desire for testing because “knowing was better than not knowing” her status. The genetic counselor respectfully responded to the threatening circumstances and demonstrated that she was following Susan’s narrative by using empathic responses to validate her understanding.

The genetic counselor recognized that while Susan understood details about the information (verbatim), she also had a gut response to the availability of testing and attraction to the option of certainty in learning whether she has the pathogenic variant (gist). Her gist response arose from a feeling judgment that living with uncertainty was inferior to living with the knowledge that she will develop ALS/FTD proteinopathy.

The case led the genetic counselor to consider Fuzzy Trace theory and the evidence that people may prefer to make decisions based on gist and that such decisions often lead to less decisional regret than those based on verbatim. As such, the counselor explored the feeling judgment with Susan who felt her gist related to a need to relieve herself of some of the uncertainty about her sons’ futures. The value of knowing her status exceeded the burden of learning she was at risk. Susan went on to explain her discomfort with uncertainty and her desire to have time to contemplate and plan for her future health. She related the close support of her husband and close friends in supporting the outcome of her decision. The genetic counselor reflected that Susan’s gist represented thoughts and feelings important to her, even though it felt to her like merely a gut feeling guiding her. Less attention was spent exploring further details about the condition or the 50 % risk as early on Susan had demonstrated clear understanding of the condition and actual risk. Instead the genetic counselor selectively reinforced Susan’s gist after deliberating the values and beliefs that were contributing to it and the potential consequences of her decision. Susan returned to the clinic for a subsequent counseling session where the genetic counselor ultimately verified Susan’s perceptions of the value in undergoing predictive testing, allowing for continued work upon learning the results.

In this case, Fuzzy trace theory offered theoretical and experimental evidence for the valuable role of gist, formulated by intrinsic feelings and thoughts that often reflect values and beliefs. While Susan demonstrated early on her understanding of the actual risk and of the condition she was at risk for, she arrived at a strong gut feeling that she needed to know. She was able to articulate some of the values and beliefs that contributed to her gist but not all of them. This case challenges common assumptions that decisions are extrinsic, rational and well articulated. Clients benefit from genetic counselors’ acceptance of the key roles that feeling judgments play within the multi-dimensional ways people make decisions.

Cognitive Behavior Theory

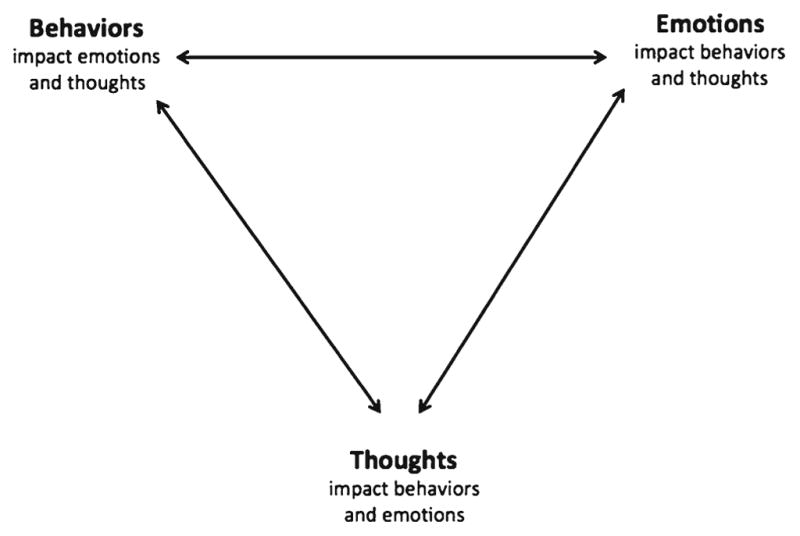

In addition to decision-making, other key psychotherapeutic aspects of genetic counseling include facilitation of effective coping, adaptation, and post-traumatic positive growth. One psychological orientation that supports these counseling goals is cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The guiding principle is that there are inherent relationships among our thoughts, behaviors and emotions (see Fig. 1). What we think affects how we act and feel, how we feel affects how we think and act, and how we act reflects how we think and feel. Much of modern psychology is steeped in CBT and significant evidence supports its efficacy (Dattilio 2000).

Fig. 1.

Cognitive Behavioral Theory Diagram

The majority of CBT-based therapies focus on cognition as the point of intervention, to effect change in emotions and/or behavior. Of note, the target is not knowledge, but cognition. This is particularly important when considering application of CBT to genetic counseling, with its inherent intertwining of medical education and psychotherapeutic counseling. CBT guides the practitioner to focus not on what the client knows about her genetic condition or risk, but what she thinks and believes, as it is her thoughts that shape her emotional experience.

Re-framing, an intervention frequently used in genetic counseling has its origin in CBT. When genetic counselors use person-first language or re-state the 3 % risk of an aneuploidy as a 97 % risk of normal chromosomes, the goal is to affect how the client thinks about his/her condition or risk. CBT techniques that can assist in facilitating coping with genetic information include identifying and challenging what are referred to in the CBT literature as “distorted thoughts” and “irrational beliefs.” These are thoughts and beliefs that are inconsistent with reality and are experienced by everyone, particularly in response to stressors. Such thoughts are frequently the source of emotional distress or maladaptive behavior and working to dispel them can lead to improved emotional and behavioral outcomes. Conversely, intentional focus on adaptive cognitions can also be beneficial to client outcomes. Since this work can involve challenging a client’s beliefs it requires a strong therapeutic alliance.

Case Example: Cognitive Behavior Theory

Robert is a 32-year-old man at 50 % risk for long QT syndrome. Long QT syndrome is an inherited arrhythmia; people with it are healthy and well, but have an increased risk for abnormal rhythms. At its worst, long QT can cause sudden death, though that risk is fairly low and the risk can be well managed by taking beta-blockers, refraining from intense exercise, avoiding QT-prolonging medications and, in select cases, using an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Genetic testing revealed that Robert inherited the familial predisposition, the electrocardiogram was abnormal, and he was diagnosed with long QT syndrome.

In this case, the genetic counselor established a strong working alliance with the client over several sessions. In discussion with the client the counselor addressed his adaptation to the diagnosis and expressed curiosity about what it’s been like for him. He conveyed that he was trying to find a way to think about it. He shared that he had been considering that it may be like having a fatal bee allergy. “It’s very unlikely that something will happen to you, but the thing that could happen to you is very serious.” Applying CBT, the genetic counselor recognized that Robert was actively engaged in his thoughts and beliefs about long QT as he appraised his new diagnosis. She engaged him in an exploration of why he’d been drawn to this analogy and what it meant to him. He reported that it allowed him to feel like he was healthy and did not have an illness, which was accurate. It also gave him a sense of confidence and activated an internal locus of control for him to use to cope with his risk of arrhythmia. Triggers can be avoided in both situations and if, in spite of prevention, a life-threatening event does occur, life-saving therapy is available (an epinephrine pen for allergies, an external or implanted defibrillator for long QT). Using a CBT-orientation, the counselor identified an opportunity to appreciate and bolster his efforts to cope with his diagnosis by thinking about it in a way that increased his sense of control.

The genetic counselor, using a psychotherapeutic approach, described Robert’s effort to make meaning of the diagnosis by making it transparent and providing an opportunity for him to confirm that she has understood him accurately. The counselor stated, “What you’re doing here is engaging in an activity where you’re figuring out how to think about long QT; what you want it to look like in your head, and considering whether this mental representation makes it feel like something you can live with successfully.” A response like this can reinforce the effort he was making to do something natural and intuitive and simultaneously help him understand its emotional benefit. This also has important implications for Robert’s behavior, because he needs to take beta-blockers everyday to reduce his chances for an adverse cardiac outcome.

The patient’s infant son later also tested positive for the familial pathogenic variant. The genetic counselor continued a CBT approach and asked, “How do you think about your son’s long QT diagnosis and how does it affect your feelings and behavior?” The patient responded, “It means having a 13-year-old dressed all in black doing heroin and never being a productive member of society because he can’t engage in sports.” Sports were a big part of Robert’s childhood, his upbringing, and his high school and college experiences. Within the safety of the working alliance with the counselor he was able to share his difficult beliefs about his son’s future. He acknowledged that he was being extreme in his response. The genetic counselor further explored its meaning and Robert shared how critical he believed sports to be to the development of character and how he had expected to rely heavily on sports in his relationship with his son. The counselor listened and explored what this meant within a respectful and trusting relationship while offering empathic responses. Then the counselor gently challenged his beliefs about what his son’s diagnosis meant for his future. CBT strategies often entail confrontation, including challenging clients on irrational beliefs. The genetic counselor further challenged Robert on whether there may be other routes to a child’s wellbeing beyond sports. CBT often involves homework. At the genetic counselor’s recommendation, Robert and his wife agreed to think and talk about alternative ways to raise their son beyond sports activities.

At two points in this case the genetic counselor’s use of CBT allowed her to recognize a specific opportunity for brief intervention to facilitate appraisals of the diagnosis. The effort was deliberate but did not take much time. The CBT counseling took 10–15 min in one session and about 10 min in the other. Use of theory can allow for efficient and parsimonious psychotherapeutic counseling by directing the counselor’s focus and interventions. This theory-guided work was supported by a strong working alliance built upon curiosity, respect and empathy.

In addition to general use of CBT in genetic counseling, specific types of CBT can be useful to genetic counseling, such as Acceptance and Commitment therapy as discussed by Broley (2013), used to help a mother of a child with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome adapt to her child’s condition.

Permission to include this case was obtained from the patient as details may be identifiable.

Conclusion

Key genetic counseling core competencies and aspects of the definition of genetic counseling are inherently psychotherapeutic. Conceptualizing genetic counseling as psychotherapy allows genetic counselors to draw from theoretical frameworks and empiric evidence from psychology and social science. Fuzzy trace theory and use of a shared decision making approach can be effective in genetic counseling when decisions are often preference based and emotionally wrought. CBT can be applied in genetic counseling cases, used by genetic counselors to help patients in making meaning of a threatening diagnosis, and ultimately to adapt to the condition. These are only two examples of how empiric findings and theoretical orientations can inform psychotherapeutic genetic counseling. Other theories can be applied to genetic counseling to guide psychotherapeutic practice and improve client outcomes. Genetic counselors can learn further about them in psychotherapy textbooks (Corey and California State 2013; Dattilio 2000).

Psychotherapeutic approaches do not need to take longer than genetic counselors have for their counseling session or than approaches they might otherwise use. Eijzenga et al. (2014) found that increased attention to psychological needs improved outcomes but did not increase session length. Yet, it is critical that genetic counselors work to help third party payers and their employers recognize that this approach is foundational to achieving meaningful positive patient outcomes, and that genetic counseling practice cannot be reduced to churning out information without helping patients process it. To make a meaningful difference to patient outcomes, genetic counselors need to help people consider the affective consequences of the information alongside the cognitive.

For genetic counselors seeking further tools for practicing a psychotherapeutic approach, one resource is to review the Genetic Counseling Outcome scale (McAllister et al. 2011). This 24-item scale includes questions such as, “I feel guilty because I (might have) passed this condition on to my children.” This scale was created to assess clinical outcomes of genetic counseling. The items were developed from interviews with patients and other stakeholders about desirable practice outcomes. As such, it can be used to inform conversations with patients about outcomes they may value, across a wide range of genetic counseling indications and practice settings. In cancer genetic counseling, research is underway using the Psychosocial Aspects of Hereditary Cancer (PAHC) questionnaire to minimize the time genetic counselors spend dominating conversations in sessions and maximize the time attending to patients’ emotions (Eijzenga et al. 2014).

Other strategies that genetic counselors can use to build a psychotherapeutic focus into their practice include devoting time to self reflection – challenging oneself to consider questions such as: “what would I have done in that session if I was taking more risk?” and “what did I avoid?” Addressing similar questions with colleagues in the context of peer supervision sessions allows for growth as a result of learning from others’ experiences and reflections too. Audiotaping one’s sessions, or asking a colleague with strong psychotherapeutic counseling skills to observe sessions and to provide feedback or mentoring can be useful strategies too. In finding a mentor who is strong in psychotherapeutic counseling, genetic counselors may consider exploring the mentors who are available through the NSGC mentorship program, and/or non-genetic counselor colleagues (e.g. psychologists, social workers) at one’s institution. These resources can be critical assets in supporting the development of psychotherapeutic genetic counseling practice.

Recommendations: Integrating a psychological theory into your psychotherapeutic practice.

Reflect on your clinical population and their psychotherapeutic counseling needs

Identify a psychological theory well suited to your population1

Learn about the theory in journal articles and textbooks1

“Shift your lens:”

View your own experiences, relationships, and needs through the lens of the theory

Examine audio recordings and written transcripts of your counseling sessions through the lens of the theory

Practice application

Try applying the theoretical approach to your own experiences

Rework transcripts or audio recordings of your sessions with application of the theory (i.e. re-write the sessions, especially your interventions and responses)

Start applying the theory in your practice

Discussion application of the theory to your practice in one-on-one or group supervision

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elizabeth Harrington for transcription of our 2015 NSGC Annual Education Conference session on this topic and to Alexis Heidlebaugh for formatting the references. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program at the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (BBB), by the Canada Research Chairs Program and BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services (JA) and by the Stanford University School of Medicine (CC).

Footnotes

A psychological counseling textbook that reviews a variety of counseling theories can greatly support your psychotherapeutic genetic counseling practice

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Barbara Biesecker reports no conflict of interest. Jehannine Austin reports no conflict of interest. Colleen Caleshu reports no conflict of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human participants conducted by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the commentary.

Animal Studies This article does not contain any studies with animals conducted by any of the authors.

References

- Accreditation Council of Genetic Counseling. Practice-based competencies for Genetic Counseling. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.gceducation.org/Documents/ACGC%20Core%20Competencies%20Brochure_15_Web.pdf.

- Ariely D. Predictably irrational: the hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York: Harper Perennial; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashtiani S, Makela N, Carrion P, Austin J. Parents’ experiences of receiving their child’s genetic diagnosis: a qualitative study to inform clinical genetics practice. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A. 2014;164a(6):1496–1502. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JC, Hippman C, Honer WG. Descriptive and numeric estimation of risk for psychotic disorders among affected individuals and relatives: implications for clinical practice. Psychiatry Research. 2012;196(1):52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J, Semaka A, Hadjipavlou G. Conceptualizing genetic counseling as psychotherapy in the era of genomic medicine. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2014;23(6):903–909. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9728-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr M. Testing for hereditary cancer predisposition: the impact of the number of options and a provider recommendation on decision-making outcomes. Johns Hopkins University; 2015. Retrieved from https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/38034. [Google Scholar]

- Broley S. Acceptance and commitment therapy in genetic counselling: a case study of recurrent worry. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2013;22(3):296–302. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey G, California State U. Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. Australia: Brooks/Cole/Cengage Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dattilio FM. Cognitive-behavioral strategies. In: Sperry JCL, editor. Brief therapy with individuals & couples. Phoenix: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen; 2000. pp. 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A, Gray J, Clarke A, Dundon J, Elwyn G, Gaff C, et al. Interventions to improve risk communication in clinical genetics: systematic review. Patient Education & Counseling. 2008;71(1):4–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijzenga W, Bleiker EM, Hahn DE, Kluijt I, Sidharta GN, Gundy C, et al. Psychosocial aspects of hereditary cancer (PAHC) questionnaire: development and testing of a screening questionnaire for use in clinical cancer genetics. Psychooncology. 2014;23(8):862–869. doi: 10.1002/pon.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington L, Kelly KM, Reblin M, Latimer S, Roter D. Communication in genetic counseling: cognitive and emotional processing. Health Communications. 2011;26(7):667–675. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.561921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Gray J, Clarke A. Shared decision making and non-directiveness in genetic counselling. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;37(2):135–138. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Lloyd A, May C, van der Weijden T, Stiggelbout A, Edwards A, et al. Collaborative deliberation: a model for patient care. Patient Education & Counseling. 2014;97(2):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erby LH, Roter D, Larson S, Cho J. The rapid estimate of adult literacy in genetics (REAL-G): a means to assess literacy deficits in the context of genetics. American Journal of Medical Genetics: Part A. 2008;146a(2):174–181. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer G, Selten R. Bounded rationality the adaptive toolbox. 2001 Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=61102.

- Horvath AO, Symonds BD. Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;38(2):139–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist. 1984;39(4):341–350. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler S. 12. The genetic counselor as psychotherapist. Birth Defects Original Articles Series. 1979;15(2):187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler S. Psychological aspects of genetic counseling. IX. Teaching and counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 1997;6(3):287–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1025676205440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd FJ, Reyna VF, Whalen P. Accuracy and ambiguity in counseling patients about genetic risk. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(20):2411–2413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.20.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Wood AM, Dunn G, Shiloh S, Todd C. The Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale: a new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services. Clinical Genetics. 2011;79(5):413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Irle J, Lobb E, Barlow-Stewart K. Assessment of the content and process of genetic counseling: a critical review of empirical studies. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2008;17(5):434–451. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM. The multidimensional measure of informed choice: a validation study. Patient Education & Counseling. 2002;48(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E, Hibbard J, Slovic P, Dieckmann N. Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk-benefit information. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(3):741–748. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy DB, Roter D, Erby LH. The role of numeracy on client knowledge in BRCA genetic counseling. Patient Education & Counseling. 2010;81(1):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta R, Biesecker BB, Bennett RL, Blum S, Hahn SE, Strecker MN, et al. A new definition of genetic counseling: National Society of genetic Counselors’ task force report. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2006;15(2):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF. A theory of medical decision making and health: fuzzy trace theory. Medical Decision Making. 2008;28(6):850–865. doi: 10.1177/0272989x08327066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, Dieckmann NF. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):943–973. doi: 10.1037/a0017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Erby L, Larson S, Ellington L. Oral literacy demand of prenatal genetic counseling dialogue: Predictors of learning. Patient Education & Counseling. 2009;75(3):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivell S, Elwyn G, Gaff CL, Clarke AJ, Iredale R, Shaw C, et al. How risk is perceived, constructed and interpreted by clients in clinical genetics, and the effects on decision making: systematic review. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2008;17(1):30–63. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Veach PM, Bartels DM, Leroy BS. Coming full circle: a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16(6):713–728. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeig JK, Munion WM. What is psychotherapy?: contemporary perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]