Abstract

Advances in podocytology and genetic techniques have expanded our understanding of the pathogenesis of hereditary steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS). In the past 20 years, over 45 genetic mutations have been identified in patients with hereditary SRNS. Genetic mutations on structural and functional molecules in podocytes can lead to serious injury in the podocytes themselves and in adjacent structures, causing sclerotic lesions such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis or diffuse mesangial sclerosis. This paper provides an update on the current knowledge of podocyte genes involved in the development of hereditary nephrotic syndrome and, thereby, reviews genotype-phenotype correlations to propose an approach for appropriate mutational screening based on clinical aspects.

Keywords: Nephrotic syndrome, Genetics, Inheritance

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a common chronic glomerular disease in children and is characterized by significant proteinuria (>40 mg/m2/hr or a spot urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio of more than 2 mg/mg) and consequent hypoalbuminemia (<3.0 g/dL), which in turn causes edema and hyperlipidemia1,2,3). Although NS is associated with many types of renal disease, the most common form (90%) in children is primary (idiopathic) NS, which develops in the absence of clinical features of nephritis or associated primary extrarenal disease. Occasionally, childhood NS can be associated with systemic inflammatory or autoimmune disease or can develop as a result of ischemic insult, infections, drugs, toxins, or inherited renal diseases1,2,3).

Most patients (approximately 90%) with idiopathic NS respond to steroid and achieve remission with a good long-term renal prognosis; however, up to 90% of responders will relapse, with approximately half of these patients becoming frequent relapsers or steroid-dependent. The remaining 10%, who continue to have proteinuria after 4 weeks of steroid therapy, are considered to have steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS). The prognosis of patients with SRNS is poor, with 50% developing end-stage renal disease (ESRD) within 15 years1,2,3,4,5). To our disappointment, steroid therapy is effective in only about 8%–10% of inherited genetic NS, which subsequently shows multidrug-resistance4,5,6). Therefore, SRNS can ensue owing to genetic, idiopathic, or multifactorial pathogenesis. However, with the increase in the identification of specific defects, cases in the idiopathic group are decreasing.

Pathologically, in most cases (~80%, according to the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children [1967–1974] or ISKDC), patients have minimal change NS, which is characterized by steroid responsiveness. In 5%–10% of NS patients (ISKDC), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is found. Less frequent histologic lesions include mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and membranous glomerulopathy7,8,9). FSGS can be classified as idiopathic, genetic, and secondary caused by injury, medication, or drug abuse based on the underlying causes. Although most histological lesions in genetic NS are unspecific, FSGS is more prevalent than other histologic types10,11,12,13). Therefore, because the majority of genetic NS is clinically steroid-resistant and FSGS is more pathologically prevalent, genetic NS is difficult to treat, has poor prognosis, and often progresses to ESRD.

Most children with SRNS present with genetic defects in podocytes. Most cases of genetic NS have monogenic causes and present as an isolated glomerular disease or a syndromic disorder with extrarenal manifestations. Molecular genetic research during the past decade has highlighted the central role of podocytes in the pathogenesis of genetic NS. The ongoing discovery of genetic defects in podocyte-related molecules has significantly added to our understanding of pathophysiology and heterogeneity in genetic NS with respect to pathophysiologic mechanisms, clinical onset, diagnostic assessments, therapeutic approaches, and prognostic judgment13,14,15,16). Although genetic testing together with clinical and biochemical investigations in genetic NS will have significant implications on the comprehensive management of NS, genetic diagnosis is far superior to histopathologic classification in predicting responsiveness to immunosuppressants and clinical outcomes13,14,15,16). Further research is needed to reveal novel mutations in identified and unknown SRNS podocyte genes. This review focuses on podocyte genes involved in the development of genetic NS and proposes the use of appropriate mutational screenings based on epidemiologic and clinical aspects.

Indications for genetic testing in NS

Genetic testing should be offered to any patient and his/her family afflicted with hereditary NS to help predict the clinical course, responsiveness to immunosuppressive drugs, rate of progression to ESRD, and risk of posttransplant recurrence; thereby, subsequent management of SRNS can be tailored accordingly13).

Although no consensus exists, appropriate genetic testing for SRNS-related mutations can be determined on the basis of current evidence in scenarios with (1) a positive family history of SRNS, (2) congenital or infantile onset (<1 year) of SRNS, (3) SRNS with onset before 25 years of age, (4) lack of response to immunosuppressive drugs, (5) histological findings of idiopathic FSGS or diffuse mesangial sclerosis (DMS) on renal biopsy, (6) presence of extrarenal manifestations (syndromes), (7) reduced renal function or renal failure, and (8) certain ethnic groups13,17).

Ongoing genotype-phenotype studies of NS patients with several genes and genetic variants have identified correlations with clear clinical significance. When supplemented with hereditary, clinical, laboratory, and/or histologic data obtained, genetic testing results would allow the clinician to refine their diagnostic and therapeutic understanding of an individual case of NS. This could guide a more accurate prognosis or family counseling for a patient or optimize the clinical decision making process in terms of prenatal diagnosis, genotype-phenotype correlations, choice of pharmacotherapy and dosage, or appropriate frequency or type of clinical monitoring, including risk assessment of recurrence after kidney transplantation18,19).

Genetic methods in hereditary NS

Historically, genetic research in NS has studied families with SRNS in order to discover rare mutations in single podocyte genes that lead to this disease13,14,20). The methodology of genetic testing is changing rapidly. Traditionally, genetic testing in diagnostic laboratories involved the Sanger sequencing of known disease-related genes. However, recent technical advances in high-throughput sequencing allow a high diagnostic yield and a continuous reduction in cost17,21,22).

Sanger sequencing is a straightforward and highly sensitive tool to test one or few genes per patient; however, in genetically heterogeneous disorders with multiple causal genes, Sanger sequencing of all known and suspected genes is time-consuming and not cost-effective23). Thereafter, Sanger sequencing for the detection of a single causational gene of SRNS has been replaced by high-throughput sequencing techniques like next-generation sequencing (NGS); however, Sanger sequencing still plays a very important role for the confirmation of genetic variants identified using high-throughput sequencing techniques.

Massive parallel NGS encompasses several high-throughput sequencing approaches and can provide the selective sequencing of a small number of genes, the coding portion of the genome (the exome), or the entire genome. Using NGS technologies, most monogenic SRNS genes can now be determined within days by utilizing a single blood test and at competitive prices compared with traditional Sanger methods. NGS can be used to identify new genes in SRNS or to simultaneously study the mutational spectrum of many genes in SRNS13,21,22,24). Gene panel analysis performed using NGS currently has higher traction in clinical use compared to whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS), because of its cost-effectiveness. Gene panels are optimized for target sequence coverage and consequently have higher read depth and accuracy compared to the WES or WGS output; however, the number of genes is limited to ~30. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) typically focus on associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms and traits such as major diseases. GWAS of cohorts of unrelated, affected subjects with SRNS can uncover disease-associated loci20). These and other approaches including enrichment and DNA pooling can complement rare variant discovery17,20,21,22).

Glomerular filtration structure

NS is a consequence of primary increase in the permselectivity barrier of the glomerular capillary wall, leading to passage of proteins through the defective filtration barrier1,2,3). Therefore, elucidating the glomerular filtration structure is mandatory for understanding the development of NS.

The glomerulus is a tuft of capillary loops supported by the mesangium, and is enclosed in a pouch-like extension of the renal tubule, known as the Bowman capsule. The glomerulus consists of 4 types of resident cells (mesangial, glomerular endothelial, visceral epithelial [known as the podocyte], and parietal epithelial), and 3 major types of matrices (mesangial, glomerular basement membrane [GBM], and Bowman basement membrane). The renal filtering apparatus of the glomerular capillary tuft consists of three major components: the inner fenestrated endothelial cell layer, the GBM, and the outer podocyte layer25,26,27).

The highly specialized and terminally differentiated podocytes branch off cytoplasmic processes to cover the outside of the glomerular capillary, with primary major, secondary minor, and tertiary processes—the so-called ‘foot processes’ (FPs)25,26,27). The podocyte cell body contains a prominent nucleus, a well-developed Golgi system, abundant rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, prominent lysosomes, and abundant mitochondria. The high density of organelles in the cell body indicates high levels of anabolic as well as catabolic activities19). In contrast to the cell body, the cytoplasmic processes contain few organelles. In the cell body and primary processes, microtubules and intermediate filaments such as vimentin and desmin dominate; whereas, microfilaments, in addition to a thin cortex of actin filaments beneath the cell membrane, densely accumulate and form loop-shaped bundles in the FPs27,28,29).

The FPs of podocytes regularly interdigitate with those from neighboring podocytes, leaving between them meandering filtration slits about 25–40 nm in width, which are bridged by the slit diaphragm (SD). The filtration slits between SDs are critical for the filtering process through the podocyte FPs and retention of protein in the blood stream26,27,30). The SD comprises nephrin and other related structural proteins that are linked intimately to the actin-based cytoskeleton through adaptor proteins such as CD2-associated protein (CD2AP), zonula occludens-1, β-catenin, Nck, and p130Cas, located at the intracellular SD insertion area near lipid rafts26,27,28,29,30,31). Signaling pathways from these SD molecules through adaptor proteins regulate podocyte structure, cell adhesion, cell survival/apoptosis, differentiation, and cellular homeostasis26,28,31).

Recently, the structures of the SD and podocyte molecules have become the mainstay of many studies, and several novel proteins have been found to be important for their function and the development of genetic and nongenetic NS.

Podocyte genes associated with hereditary NS

Currently, over 45 recessive or dominant genes have been associated with SRNS/hereditary NS in humans; the known podocyte genes explain not more than 20%–30% of hereditary NS. However, they explain 57%–100% of familial and infant-onset NS, as compared with 10%–20% of sporadic cases15,24).

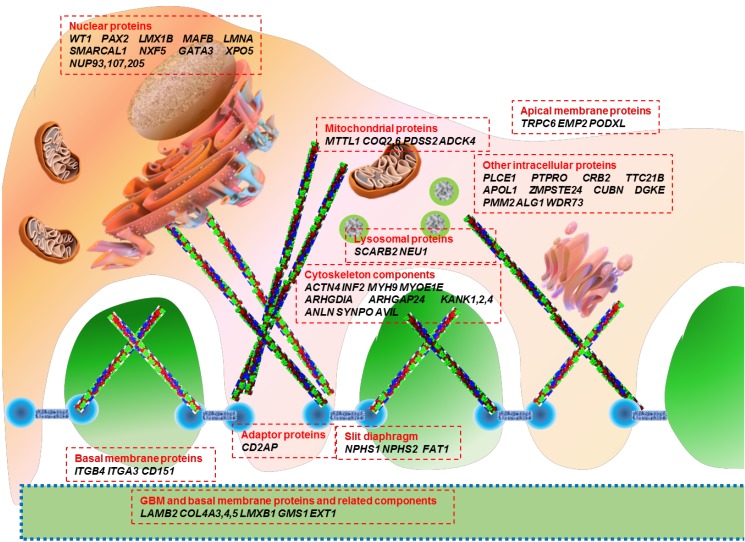

Genetic mutations affect proteins that are expressed at a variety of locations within the podocyte, including the cell membrane, nucleus, cytoskeleton, mitochondria, lysosomes, and intracellular cytoplasm (Fig. 1). The podocyte proteins uncovered so far belong to the following categories: (1) located at the SD and connected adaptor proteins, (2) involved in regulation of actin dynamics, which are essential for the maintenance of podocyte structure and function, (3) adhesive proteins at the basal membrane and GBM components, (4) apical membrane proteins related to cell polarity, (5) nuclear transcription factors, (6) proteins belonging to intracellular organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes, which are central players in podocyte metabolism, and (7) other intracellular proteins (Table 1)32,33,34,35,36).

Fig. 1. Schematic view of podocyte gene mutations associated with nephrotic syndrome indicated in Table 1.

Table 1. Genetic causes of nephrotic syndrome categorized according to the location of mutated proteins in podocytes.

| Gene | Protein | Inheritance | Locus | Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slit diaphragm and adaptor proteins | ||||

| NPHS1 | nephrin | AR | 19q13.1 | CNS, SRNS (NPHS1) |

| NPHS2 | podocin | AR | 1q25–q31 | CNS, SRNS (NPHS2) |

| PLCE1 | phospholipase C, ε1 | AR | 10q23 | DMS, SRNS (NPHS3) |

| CD2AP | CD2-associated protein | AD/AR | 6p12.3 | SRNS (FSGS3) |

| FAT1 | FAT1 | AR | 4q35.2 | NS, Ciliopathy |

| Cytoskeleton components | ||||

| ACTN4 | α-actinin-4 | AD | 19q13 | Late onset SRNS (FSGS1) |

| INF2 | inverted formin-2 | AD | SRNS (FSGS5), Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with glomerulopathy | |

| MYH9 | myosin, heavy chain 9 | AD | 22q12.3-13.1 | Macrothrombocytopenia with sensorineural deafness, Epstein syndrome, Sebastian syndrome, Fechtner syndrome |

| MYO1E | myosin IE | AR | 15q22.2 | Childhood-onset SRNS (FSGS6) |

| ARHGDIA | rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor (GDI) a1 | AR | 17q25.3 | Childhood-onset SRNS (NPHS8), seizures, cortical blindness |

| ARHGAP24 | Arhgap24 (RhoGAP) | AD | 4q22.1 | Adolescent-onset FSGS |

| ANLN | Anillin | AD | 7p14.2 | (FSGS8) |

| GBM and basal membrane proteins and related components | ||||

| LAMB2 | laminin subunit β2 | AR | 3p21 | Pierson syndrome DMS, FSGS (NPHS5) |

| ITGB4 | Integrin-β4 | AR | 17q25.1 | Epidermolysis bullosa, Anecdotic cases presenting with NS and FSGS |

| ITGA3 | Integrin-β3 | AR | Epidermolysis bullosa, Interstitial lung disease, SRNS/FSGS | |

| CD151 | Tetraspanin | AR | 11p15.5 | Epidermolysis bullosa, Sensorineural deafness, ESRD |

| EXT1 | glycosyltransferase | AR | 8q24.11 | SRNS |

| COL4A3,4 | collagen (IV) α3/α4 | AD/AR | 2q36–q37 | Alport syndrome, FSGS |

| COL4A5 | collagen (IV) α5 | XD | Xq22.3 | Alport syndrome, FSGS |

| Apical membrane proteins | ||||

| TRPC6 | transient receptor potential channel 6 | AD | 11q21–q22 | SRNS (FSGS2) |

| EMP2 | Epithelial membrane protein 2 | AD | 16p13.2 | Childhood SRNS/SSNS (MCD) (NPHS10) |

| Nuclear proteins | ||||

| WT1 | Wilms’ tumor protein | AD/AR | 11p13 | SRNS (NPHS4), Denys-Drash syndrome, Frasier syndrome, WAGR syndrome |

| LMX1B | LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-β | AD | 9q34.1 | Nail-patella syndrome, NS |

| SMARCAL1 | HepA-related protein | AR | 2q35 | Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia |

| PAX2 | Paired box gene 2 | AD | 10q24.3-q25.1 | Adult-onset FSGS (FSGS7), Renal coloboma syndrome |

| MAFB | A transcription factor | AD | 20q11.2-q13.1 | carpo-tarsal osteolysis progressive ESRD |

| LMNA | Lamins A and C | XD | 1q22 | familial partial lipodystrophy, FSGS |

| NXF5 | Nuclear RNA export factor 5 | XR | Xq21 | SRNS/FSGS cardiac conduction disorder |

| GATA3 | GATA binding protein 3 | AD | 10p14 | HDR syndrome (hypoparathyroidism, sensorineural deafness, renal abnormalities) |

| NUP93 | Nucleoporin 93kD | N/A | 16q13 | SRNS |

| NUP107 | Nucleoporin 107kD | N/A | 12q15 | Early childhood-onset SRNS/FSGS |

| Mitochondrial proteins | ||||

| COQ2 | 4-hydroxybenzoate polyprenyltransferase | AR | 4q21–q22 | Early-onset SRNS, CoQ10 deficiency |

| COQ6 | Ubiquinone biosynthesis monooxygenase COQ6 | AR | 14q24.3 | NS with sensorineural deafness, CoQ10 deficiency |

| PDSS2 | decaprenyl-diphosphate synthase subunit 2 | AR | 6q21 | Leigh syndrome, CoQ10 deficiency, FSGS |

| MTTL1 | Mitochondrially encoded tRNA leucine 1 (UUA/G) | Maternal | mtDNA | Mitochondrial diabetes, deafness with FSGS , MELAS syndrome |

| ADCK4 | aarF domain containing kinase 4 | AR | 19q13.1 | Childhood-onset SRNS (NPHS9), CoQ10 deficiency |

| Lysosomal proteins | ||||

| SCARB2 | Scavenger receptor class B, member 2 (LIMP II) | AR | 4q13–q21 | Action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome. lysosomal storage disease |

| NEU1 | Sialidase 1 | |||

| N-Acetyl-α-Neuraminidase | AR | 6p21.33 | Nephrosialidosis, SRNS | |

| Other intracellular proteins | ||||

| APOL1 | apolipoprotein L1 | AR | 22q12.3 | FSGS in African-Americans (FSGS4) |

| PTPRO | tyrosine phosphatase receptor-type O (GLEPP1) | AR | 12p12.3 | SRNS (NPHS6) |

| CRB2 | Crumbs homolog 2 | AR | 9q33.3 | Early-onset familial SRNS (FSGS9) |

| DGKE | diacylglycerol kinase-ε | AR | 17q22 | Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, membranoproliferative lesions (NPHS7) |

| ZMPSTE24 | zinc metallo-proteinase | AR | 1q34 | mandibuloacral dysplasia, FSGS |

| PMM2 | Phosphomannomutase 2 | AR | 16p13.2 | CDG syndrome, FSGS |

| ALG1 | β1,4 mannosyltransferase | AR | 16p13.3 | CDG syndrome, congenital NS |

| CUBN | Cubilin | AR | 10p13 | Childhood-onset SRNS megaloblastic anemia |

| TTC21B | IFT139 (a component of intraflagellar transport-A) | AR | 2q24.3 | Nephronophthisis (NPHP12), FSGS |

| WDR73 | WD repeat domain 73 | AR | 15q25.2 | Galloway-Mowat syndrome, SRNS/FSGS |

ACTN4, actinin-alpha 4; ADCK4, AarF domain containing kinase 4; AD, autosomal-dominant; ALG1, asparagine-linked glycosylation protein 1; ANLN, anillin; APOL1 apolipoprotein L1; AR, autosomal-recessive; ARHGAP24, Rho GTPase-activating protein 24; ARHGDIA, Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) alpha; CD2AP, CD2-associated protein; CDG syndrome, congenital disorders of glycosylation; CNS, congenital nephrotic syndrome; COQ2, coenzyme Q2 4-hydroxybenzoate polyprenyltransferase; COQ6, coenzyme Q6 monooxygenase; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; CRB2, Crumbs family member 2; DGKE, diacylglycerol kinase epsilon; DMS, diffuse mesangial sclerosis; EMP2, epithelial membrane protein 2; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; EXT1, exotosin 1; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; GLEPP-1, glomerular epithelial cell protein 1; HDR syndrome, hypoparathyroidism, sensorineural deafness, and renal abnormalities; ITGA3, integrin alpha 3; ITGB4, integrin beta 4; INF2, inverted formin, FH2 and WH2 domain containing; LAMB2, laminin beta 2; LIMP2, lysosome membrane protein 2; LMX1B, LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 beta; MAFB, v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B; MELAS syndrome, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; MTTL1, mitochondrially encoded tRNA leucine 1 (UUA/G); MYH9, myosin heavy chain 9, non-muscle; MYO1E, Homo sapiens myosin IE; N/A, not available; NPHS1, nephrin; NPHS2, podocin; NS, nephrotic syndrome; NUP93, Nucleoporin 93 kD; NUP107, Nucleoporin 107 kD; PDSS2, prenyl (solanesyl) diphosphate synthase, subunit 2; PLCE1, phospholipase C, epsilon 1; PTPRO, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O; SCARB2, scavenger receptor class B, member 2; SMARCAL, SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a-like 1; SRNS, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome; TRPC6, transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 6; TTC21B, Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 21B; WAGR syndrome, Wilms' tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies and mental retardation syndrome; WDR73, WD repeat domain 73; WT1, Wilms' tumor 1.

Genotype-phenotype correlations in monogenic SRNS

Advances in podocytology and genetic techniques have expanded our understanding of the pathogenesis of hereditary SRNS, and have accelerated elucidation of the mechanism of normal and pathologic glomerular filtration through podocytes. Further, knowledge on genetic and nongenetic podocytopathies add to the genetic and phenotypic data. Genotype-phenotype correlations in hereditary NS have been explained well, and will be reviewed here.

1. Recessive versus dominant inheritance

There is significant phenotypic variability associated with defects in NS-related genes. Recessive mutations in NPHS1, NPHS2, LAMB2, and PLCE1 cause severe clinical features of early-onset NS and progress to ESRD, either during infancy or throughout childhood. Recessive mutations in CD2AP and MYO1E cause severe childhood-onset NS and progress to ESRD later. Hereditary, autosomal-dominant NS is rare, occurring mostly in juvenile and adult familial cases. Dominant mutations in ACTN4, TRPC6, and INF2 are associated with late-onset proteinuria and progress to ESRD during the third and fourth decades of life13,14,17,37). Inheritance patterns for recently reported genetic mutants responsible for hereditary NS are listed in Table 1.

For recessive mutations, family history is unlikely, because parents of individuals harboring such mutations will be healthy heterozygous carriers, and no one in the ancestry will have had disease (because if there is any inherited mutation, it will be heterozygous). For dominant mutations, one of the parents of the affected individual will most likely be affected, and the disease may have been handed down through multiple generations (except for situations of de novo mutations or incomplete penetrance, which can occur in case of autosomal-dominant genes). Thereby, the detection of dominant mutations has important clinical implications in situations of living-related donor selection in kidney transplantation17).

2. Age-at-onset and specific genes

NS that presents at birth or within the first 3 months of life is termed congenital nephrotic syndrome (CNS), while the term infantile nephrotic syndrome (INS) is used for NS presenting between 3 and 12 months of age. Later-onset NS includes early/late childhood (1–5 years/thereafter) and adult-onset NS.

CNS is usually caused by a defect in a major podocyte SD gene, nephrin (NPHS1), associated with Finnish type nephropathy. In non-Finnish populations, CNS is actually a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders caused by mutations in WT1, PLCE1, LAMB2, or NPHS2. Therefore, early-onset NS (CNS and INS) is usually caused by mutations in NPHS1, or less commonly by mutations in WT1, PLCE1, LAMB2, NPHS2I, or LMX1B14,32,33,34,37,38,39,40). Patients with CNS mostly presented steroid-resistant proteinuria in the first few days of life, and rapidly progressed to ESRD by the age of 2–8 years; NPHS1 mutations were detected in more than half of all cases. However, some NPHS1 mutations are associated with ESRD occurring after the age of 20 years38,41,42,43,44). As an example, a case series from New Zealand reported that Maori children with CNS have indolent clinical course and prolonged renal survival44). Mutations in TRPC6, CD2AP, or MYO1E cause severe childhood-onset NS.

Most cases of adult-onset familial FSGS are inherited as autosomal-dominant disease. The most common causative gene is INF2 (up to 17%); other mutations include those in TRPC6 (up to 12%), ACTN4 (3.5%), PAX2, and SCARB215). However, penetrance is often incomplete, with variable expression. Many adult patients with familial FSGS present with nonnephrotic proteinuria.

3. Renal pathology

Podocytopathies include 4 histologic patterns of glomerular injury: (1) minimal change nephropathy (MCN), if the number of podocytes per glomerulus is unchanged; (2) FSGS, if there is podocytopenia with segmental glomerulosclerosis; (3) DMS, where low proliferative index has been described; or (4) collapsing glomerulopathy, if there is marked podocyte proliferation with collapsed capillaries45,46). For specific genes and specific mutations within the same gene of podocytes, there can be a correlation between genotypes and renal histologic patterns17,37).

In infants (CNS and INS) DMS was a frequent histologic finding, whereas FSGS was observed in up to 90% of individuals with proteinuria onset at 7 to 25 years47). Individuals with CNS and the renal histology of DMS usually have mutations in the following genes: PLCE1, LAMB2, WT1, NPHS1, NPHS2, or GMS1; however, MCN and FSGS are rarely seen in CNS17,37,38,46,47). Data from human genetics and from mouse models of SRNS/FSGS show that the renal histologic patterns of DMS and FSGS lie at different ends of the spectrum of a shared pathogenesis. This means that “severe” recessive mutations (protein-truncating mutations) in NPHS2 cause a fetal-onset renal “developmental” phenotype of immature glomeruli (i.e., DMS), whereas “mild” mutations (missense mutations) in the same gene, NPHS2, cause the late feature of renal “degenerative” phenotype, FSGS17,48). Irregular microcystic dilation of the proximal tubules is a characteristic histologic feature in patients with mutations in NPHS1; and this condition may be useful for differentiating patients with NPHS1 mutations from those with NPHS2 mutations; however, this is not observed in all cases38).

Familial FSGS may have clinical characteristics that are similar to sporadic FSGS, but the prognosis is different. Patients with familial FSGS tend to be unresponsive to steroid therapy. Thus, when abundant proteinuria is present, the prognosis of familial FSGS is poor15,49).

4. Syndromic versus nonsyndromic NS

Mutations in specific SRNS genes may cause distinct clinical phenotypes in a gene-specific and/or allele-specific manner17,48). Genes implicated in nonsyndromic podocytopathies are NPHS1, NPHS2, CD2AP, PLCE1, ACTN4, TRPC6, INF2, and others14,15,17,50). In syndromic forms of FSGS, the extrarenal manifestations are most prominent and often diagnostic. Syndromic forms of SRNS, which are far less frequent, may be a result of mutations in genes encoding transcriptional factors (WT1, LMX1B), GBM components (LAMB2, ITGB4), lysosomal (SCARB2) and mitochondrial (COQ2, PDSS2, MTTL1) proteins, a DNA-nucleosome restructuring mediator (SMARCAL1) or cytoskeletal proteins, including inverted formin 2 (INF2) and nonmuscle myosin IIA (MYH9)14,15,17,51).

Mutations in the WT1 gene, encoding the Wilms' tumor 1 protein, which typically lead to Denys-Drash syndrome or Frasier syndrome, can also cause isolated SRNS52). In addition, mutations in LAMB2, encoding laminin-β2, are usually implicated in Pierson syndrome associated with neuronal or retinal involvement53,54). Individuals with LMX1B mutations usually present with Nail-Patella syndrome. However, specific LMX1B mutations have been found in individuals with isolated SRNS55). INF2 mutations can either lead to isolated NS or be present in individuals with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease56). MYH9, a podocyte-expressed gene encoding non-muscle myosin IIA, has been identified as the disease-causing gene in the rare giant-platelet disorders, including May-Hegglin anomaly, Epstein-Fechtner, or Sebastian syndrome57). Genetic causes of most syndromic NS are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Genetic causes of important syndromic nephrotic syndrome.

| Gene | Protein | Inheritance | Phenotypes | Renal pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 | Wilms’ tumor protein | AD | Denys-Drash syndrome | DMS |

| AD | Frasier syndrome, | FSGS | ||

| AD | WAGR syndrome | |||

| AR | SRNS (NPHS4) | DMS, FSGS | ||

| LAMB2 | laminin subunit β2 | AR | Pierson syndrome | DMS |

| NPHS5 | FSGS | |||

| LMX1B | LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 | AD | Nail-patella syndrome | FSGS |

| Microalbuminuria, NS | ||||

| MYH9 | myosin, heavy chain 9 | AD | Macrothrombocytopenia with sensorineural deafness | FSGS |

| Epstein syndrome | ||||

| Sebastian syndrome | ||||

| Fechtner syndrome | ||||

| SCARB2 | Scavenger receptor class B, member 2 (LIMP II) | AR | Action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome | FSGS |

| lysosomal storage disease | Collapsing glomerulopathy | |||

| MTTL1 | Mitochondrially encoded tRNA leucine 1 (UUA/G) | Maternal | MELAS syndrome | FSGS |

| Mitochondrial diabetes deafness with FSGS | ||||

| PDSS2 | decaprenyl-diphosphate synthase subunit 2 | AR | Leigh syndrome | FSGS |

| CoQ10 deficiency | ||||

| SRNS | ||||

| WDR73 | WD repeat domain 73 | AR | Galloway-Mowat syndrome | FSGS or DMS |

| SRNS | ||||

| SMARCAL1 | HepA-related protein | AR | Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia | FSGS |

| Early-onset SRNS/ESRD | ||||

| PAX2 | Paired box gene 2 | AD | Renal coloboma syndrome | FSGS |

| Adult-onset FSGS (FSGS7) |

AD, autosomal-dominant; AR, autosomal-recessive; CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; DMS, diffuse mesangial sclerosis; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; LAMB2, laminin beta 2; LIMP2, lysosome membrane protein 2; LMX1B, LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 beta; MELAS syndrome, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; MTTL1, mitochondrially encoded tRNA leucine 1 (UUA/G); MYH9, myosin heavy chain 9, non-muscle; MYO1E, Homo sapiens myosin IE; PDSS2 prenyl (solanesyl) diphosphate synthase, subunit 2; SCARB2 scavenger receptor class B, member 2; SMARCAL: SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a-like 1; SRNS, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome; WAGR syndrome, Wilms' tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies and mental retardation syndrome; WDR73, WD repeat domain 73; WT1, Wilms' tumor 1; AD, autosomal-dominant; AR, autosomal-recessive; NS nephrotic syndrome.

Conclusions

According to genotype-phenotype correlations in hereditary NS, an appropriate genetic approach for patients with hereditary NS could be determined based on inheritance, age at onset, renal histology, and presence of extrarenal malformations.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by the Clinical Research Fund of Chungbuk National University Hospital and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2013R1A1A4A03006207).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Eddy AA, Symons JM. Nephrotic syndrome in childhood. Lancet. 2003;362:629–639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiggins RC. The spectrum of podocytopathies: a unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1205–1214. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha A, Bagga A. Nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0776-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JS, Bellew CA, Silverstein DM, Aviles DH, Boineau FG, Vehaskari VM. High incidence of initial and late steroid resistance in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1275–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mekahli D, Liutkus A, Ranchin B, Yu A, Bessenay L, Girardin E, et al. Long-term outcome of idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: a multicenter study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1525–1532. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Büscher AK, Kranz B, Büscher R, Hildebrandt F, Dworniczak B, Pennekamp P, et al. Immunosuppression and renal outcome in congenital and pediatric steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2075–2084. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01190210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McTaggart SJ. Childhood urinary conditions. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:937–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava T, Simon SD, Alon US. High incidence of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in nephrotic syndrome of childhood. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s004670050555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Agati VD. The spectrum of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:271–281. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f94a96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woroniecki RP, Kopp JB. Genetics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0445-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrandt F. Genetic kidney diseases. Lancet. 2010;375:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60236-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caridi G, Trivelli A, Sanna-Cherchi S, Perfumo F, Ghiggeri GM. Familial forms of nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:241–252. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1051-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi S, Andersen R, Jespersen B, Rittig S. Genetics of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: a review of mutation spectrum and suggested approach for genetic testing. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:844–856. doi: 10.1111/apa.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benoit G, Machuca E, Antignac C. Hereditary nephrotic syndrome: a systematic approach for genetic testing and a review of associated podocyte gene mutations. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1621–1632. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1495-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rood IM, Deegens JK, Wetzels JF. Genetic causes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: implications for clinical practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:882–890. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gbadegesin RA, Winn MP, Smoyer WE. Genetic testing in nephrotic syndrome-challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovric S, Ashraf S, Tan W, Hildebrandt F. Genetic testing in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: when and how? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:1802–1813. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrodi SJ, Mukherjee S, Shan Y, Tromp G, Sninsky JJ, Callear AP, et al. Genetic-based prediction of disease traits: prediction is very difficult, especially about the future. Front Genet. 2014;5:162. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampson MG, Pollak MR. Opportunities and challenges of genotyping patients with nephrotic syndrome in the genomic era. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampson MG, Hodgin JB, Kretzler M. Defining nephrotic syndrome from an integrative genomics perspective. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:51–63. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2857-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renkema KY, Stokman MF, Giles RH, Knoers NV. Next-generation sequencing for research and diagnostics in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:433–444. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown EJ, Pollak MR, Barua M. Genetic testing for nephrotic syndrome and FSGS in the era of next-generation sequencing. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1030–1038. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neveling K, Feenstra I, Gilissen C, Hoefsloot LH, Kamsteeg EJ, Mensenkamp AR, et al. A post-hoc comparison of the utility of sanger sequencing and exome sequencing for the diagnosis of heterogeneous diseases. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:1721–1726. doi: 10.1002/humu.22450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy HJ, Bierzynska A, Wherlock M, Ognjanovic M, Kerecuk L, Hegde S, et al. Simultaneous sequencing of 24 genes associated with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:637–648. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07200712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mundel P, Shankland SJ. Podocyte biology and response to injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:3005–3015. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000039661.06947.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrakka J, Tryggvason K. Molecular make-up of the glomerular filtration barrier. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavenstädt H, Kriz W, Kretzler M. Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:253–307. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faul C, Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Kim K, Mundel P. Actin up: regulation of podocyte structure and function by components of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh GI, Saleem MA. The podocyte cytoskeleton: key to a functioning glomerulus in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;8:14–21. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiser J, Kriz W, Kretzler M, Mundel P. The glomerular slit diaphragm is a modified adherens junction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ha TS. Roles of adaptor proteins in podocyte biology. World J Nephrol. 2013;2:1–10. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v2.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machuca E, Benoit G, Antignac C. Genetics of nephrotic syndrome: connecting molecular genetics to podocyte physiology. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R2):R185–R194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy HJ, Saleem MA. Genetics in clinical practice: nephrotic and proteinuric syndromes. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;118:e1–e8. doi: 10.1159/000320878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akchurin O, Reidy KJ. Genetic causes of proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome: impact on podocyte pathobiology. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:221–233. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2753-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YM, Liapis H. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: molecular genetics and targeted therapies. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:101. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bierzynska A, Soderquest K, Koziell A. Genes and podocytes - new insights into mechanisms of podocytopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;5:226. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kari JA, Montini G, Bockenhauer D, Brennan E, Rees L, Trompeter RS, et al. Clinico-pathological correlations of congenital and infantile nephrotic syndrome over twenty years. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:2173–2180. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machuca E, Benoit G, Nevo F, Tête MJ, Gribouval O, Pawtowski A, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in non-Finnish congenital nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1209–1217. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinkes BG, Mucha B, Vlangos CN, Gbadegesin R, Liu J, Hasselbacher K, et al. Nephrotic syndrome in the first year of life: two thirds of cases are caused by mutations in 4 genes (NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, and LAMB2) Pediatrics. 2007;119:e907–e919. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heeringa SF, Vlangos CN, Chernin G, Hinkes B, Gbadegesin R, Liu J, et al. Thirteen novel NPHS1 mutations in a large cohort of children with congenital nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:3527–3533. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patrakka J, Kestilä M, Wartiovaara J, Ruotsalainen V, Tissari P, Lenkkeri U, et al. Congenital nephrotic syndrome (NPHS1): features resulting from different mutations in Finnish patients. Kidney Int. 2000;58:972–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koziell A, Grech V, Hussain S, Lee G, Lenkkeri U, Tryggvason K, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations of NPHS1 and NPHS2 mutations in nephrotic syndrome advocate a functional inter-relationship in glomerular filtration. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:379–388. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schultheiss M, Ruf RG, Mucha BE, Wiggins R, Fuchshuber A, Lichtenberger A, et al. No evidence for genotype/phenotype correlation in NPHS1 and NPHS2 mutations. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1340–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong W, Morris MC, Kara T. Congenital nephrotic syndrome with prolonged renal survival without renal replacement therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:2313–2321. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. A proposed taxonomy for the podocytopathies: a reassessment of the primary nephrotic diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:529–542. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04121206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. Advances in the biology and genetics of the podocytopathies: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:201–216. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadowski CE, Lovric S, Ashraf S, Pabst WL, Gee HY, Kohl S, et al. A single-gene cause in 29.5% of cases of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1279–1289. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hildebrandt F, Heeringa SF. Specific podocin mutations determine age of onset of nephrotic syndrome all the way into adult life. Kidney Int. 2009;75:669–671. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conlon PJ, Butterly D, Albers F, Rodby R, Gunnells JC, Howell DN. Clinical and pathologic features of familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:34–40. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh L, Singh G, Dinda AK. Understanding podocytopathy and its relevance to clinical nephrology. Indian J Nephrol. 2015;25:1–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.134531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zenker M, Machuca E, Antignac C. Genetics of nephrotic syndrome: new insights into molecules acting at the glomerular filtration barrier. J Mol Med (Berl) 2009;87:849–857. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chernin G, Vega-Warner V, Schoeb DS, Heeringa SF, Ovunc B, Saisawat P, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlation in nephrotic syndrome caused by WT1 mutations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1655–1662. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09351209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zenker M, Aigner T, Wendler O, Tralau T, Müntefering H, Fenski R, et al. Human laminin beta2 deficiency causes congenital nephrosis with mesangial sclerosis and distinct eye abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2625–2632. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hasselbacher K, Wiggins RC, Matejas V, Hinkes BG, Mucha B, Hoskins BE, et al. Recessive missense mutations in LAMB2 expand the clinical spectrum of LAMB2-associated disorders. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1008–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyer O, Woerner S, Yang F, Oakeley EJ, Linghu B, Gribouval O, et al. LMX1B mutations cause hereditary FSGS without extrarenal involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1216–1222. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boyer O, Nevo F, Plaisier E, Funalot B, Gribouval O, Benoit G, et al. INF2 mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with glomerulopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2377–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seri M, Cusano R, Gangarossa S, Caridi G, Bordo D, Lo Nigro C, et al. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May-Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. The May-Heggllin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]