Main Text

Viroimmunotherapy has emerged as a powerful cancer therapy because oncolytic viruses are immunogenic and can initiate an anti-tumor response.1 Preclinical and clinical results using a herpes simplex virus-based oncolytic virus (T-VEC) have provided considerable evidence that viroimmunotherapy can control both local (treated with viral vector) and metastasized (untreated) tumors by activating host anti-tumor immune responses in patients with advanced melanoma.2 Since there is now clear evidence that the host immune response contributes to long-term tumor control in viroimmunotherapy-treated patients, preclinical models and clinical trials have tested the combination of checkpoint inhibitors with viroimmunotherapies to boost host antitumor immune responses. T-VEC and ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) were recently tested together in patients with advanced melanoma, and this combination appeared to have greater efficacy than T-VEC or ipilimumab alone.3 Another approach to enhance the anti-tumor effects of viroimmunotherapy has been to combine viroimmunotherapy with adoptively transferred antigen-specific T cells (adoptive cell therapy [ACT]). Two types of ACT product are widely used. The first is amplified from tumor-infiltrated lymphocytes that recognize tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) through their T cell receptors (TCRs). These T cells have induced durable complete regressions in patients with melanoma.4 The second T cell product is amplified from peripheral blood mononuclear cells, after which T cells are genetically modified to express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells) for relevant cancer cell surface antigens. Striking clinical successes against B cell malignancies have been reported using CAR T cells targeting CD19 (Porter et al.5). In this issue of Molecular Therapy, Shim et al.6 evaluate whether combination of all three agents (VSV-TAA, ACT, and a checkpoint inhibitor) maximizes anti-tumor effects in syngeneic melanoma animal models.

Previously, the authors’ group has shown that systemic treatment with an enveloped RNA virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), expressing TAAs mounts systemic anti-tumor responses against disseminated metastatic disease.7 Additionally, they combined systemic VSV-TAA with tumor-specific adoptive T cell transfer and showed that this two-pronged approach had superior anti-tumor effects compared to single agent treatments.8 Cockle et al.9 also reported that combination of systemic VSV-TAA with a checkpoint inhibitor enhanced anti-tumor effects by de-repressing tumor-specific Th1 and Th17 T cells in a syngeneic glioma mouse model.

In the study by Shim et al.,6 the authors first confirmed that combining VSV-TAA (gp100) with ACT (Pmel CD8+ T cells) significantly improves anti-tumor effects compared to treatment with single agents alone in oligometastatic (limited systemic metastatic tumors for which local ablative therapy could be curative) syngeneic mouse models of melanoma. They next confirmed that endogenous CD8+ T cells are increased in the blood and spleen of VSV-treated mice and that these increased CD8+ T cells express high levels of PD-1 and TIM-3. The authors then compared the anti-tumor effects of VSV-TAA and ACT in the presence or absence of checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1 antibody or anti-TIM-3 antibody) in different single metastatic melanoma syngeneic mouse models. Surprisingly, given the observed T cell phenotypes, the authors found that the presence of checkpoint inhibitors had little to no impact on animal survival. They subsequently quantified and phenotyped the endogenous T cells and ACTs in the blood of these mice at different time points and found that checkpoint inhibitors induced minimal expansion of endogenous CD8+ T cells, but no expansion of ACTs, over time. The authors re-challenged mice surviving more than 190 days with the same cancer cells to confirm whether checkpoint treatment increases the activity of endogenous CD8+ effector T cells. However, there was no difference between the number and activity of T cells in the absence or presence of checkpoint inhibitors in this re-challenge model. The authors, therefore, hypothesized that excess amounts of tumor-specific T cells are required for checkpoint inhibitors to improve anti-tumor efficacy. To test this idea, they transplanted cancer cells into Pmel transgenic mice (the source of ACT in this study) and evaluated the anti-tumor effect of VSV-TAA in the presence or absence of anti-PD-1 antibody. Although CD8+ T cells in these transgenic mice expressed high levels of PD-1, the anti-PD-1 antibody gave rise to only a modest improvement in the anti-tumor effect.

Despite the attractive features of testing combined immunotherapy agents in preclinical models, there are some potentially confounding issues. First, the timing and dosage of checkpoint inhibitor treatment are difficult to correlate with what is used in patients. The half-life of checkpoint inhibitors in patient blood is generally about 3 weeks, and patients receive checkpoint inhibitors at less than 10 mg/kg dosages every 4–6 weeks.10 However, most groups combining viroimmunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors in preclinical models treat with checkpoint inhibitors every 2–3 days at a dose of 10 mg/kg.11 We really do not know whether this regimen accurately reflects the doses received by patients treated with viroimmunotherapy (e.g., T-VEC). Recent RNA sequencing (RNAseq) analysis of CD8+ T cells in syngeneic animal models of melanoma indicated that TIM-3 and PD-1 are markers of both activation and exhaustion,12 suggesting that early blockade of PD-1 or TIM-3, as performed in this study, might suppress T cell activation as opposed to attenuating exhaustion.

A second remaining question is whether it is better to block checkpoint receptors on T cells (e.g., PD-1, TIM-3, or CTLA-4) or block their cognate ligands on cancer cells (e.g., PD-L1, Galectin-9). Although combining viroimmunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors targeting effector cells (e.g., anti-PD-1 antibody or anti-CTLA-4 antibody) has been shown to have an additive anti-tumor effect in pre-clinical models and clinical trials,11 the authors’ data suggest that blockade of checkpoint receptors does not significantly benefit native T cells or ACTs. We recently reported that local blockade of PD-L1 on cancer cells significantly improved the anti-tumor effects of combinatorial treatment with oncolytic adenovirus (Onc.Ad) and CAR T cells in xenograft animal models.13 However, we also found that systemic treatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody prior to CAR T cell infusion had no additive anti-tumor effect compared to combination therapy alone because of a reduction in circulating CAR T cells resulting from the anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment (but not isotype antibody) in our xenograft models. Thus, our data suggest that targeting, localization, and treatment timing are all important factors that must be optimized for this kind of combinatorial treatment.

A third confounding factor is whether the host immune activation triggered by checkpoint inhibitors impacts the oncolytic effects of viral vectors. The authors’ data clearly indicate that systemic VSV-TAA treatment induced the development of anti-VSV CTLs and that these CTLs were PD-1- and/or TIM-3 positive. However, the authors did not confirm whether anti-PD-1 antibody or anti-TIM-3 antibody treatment had an impact on VSV persistence at the tumor site. If anti-VSV CTLs actively eliminate VSV-infected cells following administration of checkpoint inhibitors, they might reduce the anti-tumor effects of VSV-TAA. This point may need to be addressed in a future study.

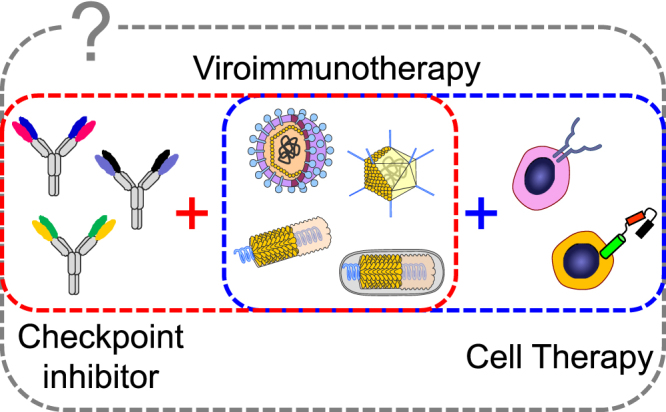

In conclusion, the article by Shim et al.6 highlights the importance of carefully considering what therapies we partner with viroimmunotherapy. Although combining immunotherapy agents with different mechanisms of action appears to be the new standard for cancer immunotherapy and remains an attractive approach to cure advanced malignancies (Figure 1), this approach requires careful consideration of multiple parameters. Additionally, preclinical studies of combinatorial therapies require appropriate control groups for each agent. Testing these immunotherapy candidates in immunocompetent mouse models is paramount before human clinical trials and should enable rapid evaluation of the best combinations for clinical studies. This approach holds promise, not only to improve patient outcomes, but also to assess the contribution of the host immune system to treatment regimens.

Figure 1.

Combining Multiple Immunotherapy Agents with Different Mechanisms of Action Will Be the New Standard of Cancer Immunotherapy

Combination of viroimmunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors or cell therapy has enhanced anti-tumor effects in pre-clinical models and clinical trials. However, which combination of these three agents maximizes anti-tumor effects remains unknown.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Catherine Gillespie at the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy at Baylor College of Medicine for editing the paper. The author received supports for his cancer immunotherapy research from NIH grant R00HL098692, a BCM Head and Neck seed grant, and the Concern Foundation.

References

- 1.Kaufman H.L., Kohlhapp F.J., Zloza A. Oncolytic viruses: a new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:642–662. doi: 10.1038/nrd4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andtbacka R.H., Kaufman H.L., Collichio F., Amatruda T., Senzer N., Chesney J., Delman K.A., Spitler L.E., Puzanov I., Agarwala S.S. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puzanov I., Milhem M.M., Minor D., Hamid O., Li A., Chen L., Chastain M., Gorski K.S., Anderson A., Chou J. Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination With Ipilimumab in Previously Untreated, Unresectable Stage IIIB-IV Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2619–2626. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg S.A., Restifo N.P. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2015;348:62–68. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter D.L., Hwang W.T., Frey N.V., Lacey S.F., Shaw P.A., Loren A.W., Bagg A., Marcucci K.T., Shen A., Gonzalez V. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:303ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shim K.G., Zaidi S., Thompson J., Kottke T., Evgin L., Rajani K.R., Schuelke M., Driscoll C.B., Huff A., Pulido J.S., Vile R.G. Inhibitory receptors induced by VSV viroimmunotherapy are not necessarily targets for improving treatment efficacy. Mol Ther. 2017;25:962–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.01.023. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulido J., Kottke T., Thompson J., Galivo F., Wongthida P., Diaz R.M., Rommelfanger D., Ilett E., Pease L., Pandha H. Using virally expressed melanoma cDNA libraries to identify tumor-associated antigens that cure melanoma. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:337–343. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rommelfanger D.M., Wongthida P., Diaz R.M., Kaluza K.M., Thompson J.M., Kottke T.J., Vile R.G. Systemic combination virotherapy for melanoma with tumor antigen-expressing vesicular stomatitis virus and adoptive T-cell transfer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4753–4764. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockle J.V., Rajani K., Zaidi S., Kottke T., Thompson J., Diaz R.M., Shim K., Peterson T., Parney I.F., Short S. Combination viroimmunotherapy with checkpoint inhibition to treat glioma, based on location-specific tumor profiling. Neuro-oncol. 2016;18:518–527. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer J.R., Drake C.G., Wollner I., Powderly J.D., Picus J., Sharfman W.H., Stankevich E., Pons A., Salay T.M., McMiller T.L. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampath P., Thorne S.H. Novel therapeutic strategies in human malignancy: combining immunotherapy and oncolytic virotherapy. Oncolytic Virother. 2015;4:75–82. doi: 10.2147/OV.S54738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer M., Wang C., Cong L., Marjanovic N.D., Kowalczyk M.S., Zhang H., Nyman J., Sakuishi K., Kurtulus S., Gennert D. A distinct gene module for dysfunction uncoupled from activation in tumor-infiltrating T cells. Cell. 2016;166:1500–1511.e1509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanoue K., Rosewell Shaw A., Watanabe N., Porter C.E., Rana B., Gottschalk S., Brenner M.K., Suzuki M. Armed oncolytic adenovirus expressing PD-L1 mini-body enhances anti-tumor effects of chimeric antigen receptor T-cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2017 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1577. Published online February 24, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]