Abstract

In vitro prevascularization of engineered tissue constructs promises to enhance their clinical applicability. We hypothesize that adult endothelial cells (ECs), isolated from limb veins of elderly patients, bear the vasculogenic properties required to form vascular networks in vitro that can later integrate with the host vasculature upon implantation. Here, we show that adult ECs formed vessel networks that were more developed and complex than those formed by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) seeded with various supporting cells on three-dimensional (3D) biodegradable polymer scaffolds. In parallel, secreted levels of key proangiogenic cytokines were significantly higher in adult EC-bearing scaffolds as compared to HUVEC scaffolds. As a proof of concept for applicability of this model, adult ECs were co-seeded with human myoblasts as well as supporting cells and successfully formed a branched network, which was surrounded by aligned human myotubes. The vascularized engineered muscle tissue implanted into a full-thickness defect in immunodeficient mice remained viable and anastomosed with the host vasculature within 9 days of implantation. Functional “chimeric” blood vessels and various types of anastomosis were observed. These findings provide strong evidence of the applicability of adult ECs in construction of clinically relevant autologous vascularized tissue.

Keywords: endothelial cells, tissue engineering, neovascularization, cell therapy

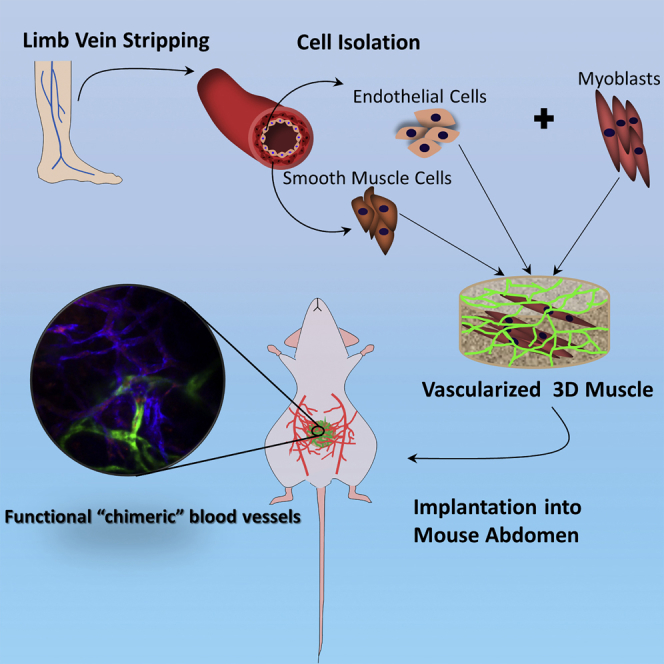

Graphical Abstract

Levenberg and colleagues show that co-culture of venous endothelial cells from adult patients and myoblasts can form a 3D vascularized muscle that can successfully integrate with the host tissue after implantation into the mouse abdomen. Data support the applicability of these cells in construction of clinically relevant autologous vascularized muscle.

Introduction

Vascularization is a major challenge when attempting to apply tissue engineering approaches for large-scale clinical purposes.1, 2, 3 Co-culture of tissue-specific cells with endothelial cells (ECs) has been shown to support and accelerate formation of vessel-like structures within engineered tissue, potentially increasing their clinical applicability.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Most studies conducted to date have tested continuous endothelial cell lines or human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)4, 9, 10, 11 in in vitro or immunodeficient mouse models. Yet, clinical application of such cells would require administration of immunosuppressive drugs. Integration of autologous cells into engineered tissues would circumvent the need for immunosuppressive therapy following transplantation. Currently, autologous muscle flaps provide the best outcome in treatment of significant muscle tissue loss but involve donor site morbidity and are still associated with low success rates.12, 13, 14 Therefore, numerous attempts have been made to engineer a vascularized, three-dimensional (3D) muscle tissue closely mimicking native muscle.4, 5, 9, 15, 16 The majority of the reports describe the use of a combination of both human and murine cells to achieve vascularization. To date, there have been no reports of integration of ECs derived from elderly patient vessels, to induce vascularization in engineered tissue. Grossman et al.17 described the isolation of autologous adult ECs and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) from limb veins of elderly patients, followed by their intra-arterial injection at sites of peripheral artery disease (PAD)-induced claudication. Phase I/II clinical trials demonstrated their safety and promising clinical efficacy in expanding and creating new collateral arteries. However, prior to adoption of these cells for creation of engineered vascularized tissues, their vascularization potential, both in vitro and in vivo, should be further be evaluated.

With the long-term goal of constructing a functional, implantable muscle graft, this work assessed the ability of ECs isolated from limb veins of elderly patients, to form vessel networks when co-cultured with various types of supporting cells (human neonatal dermal fibroblasts [HNDFs], adult fibroblasts, and/or SMCs) and human myoblasts. Using a protocol previously established in our laboratory, the multicellular cultures were seeded on poly (L-lactic acid) (PLLA)/polylactic-glycolic acid (PLGA) sponges, together with fibrin, an established vascularization enhancer.4 Once branched networks were detected within the engineered muscle graft, the grafts were implanted into full-thickness defects created in the abdominal wall of immunodeficient nude mice. Graft integration and anastomosis with the host vasculature were observed within 9 days, providing evidence for the vasculogenic potential of adult venous ECs.

Results

In Vitro Vessel Network Development on PLLA/PLGA Scaffolds

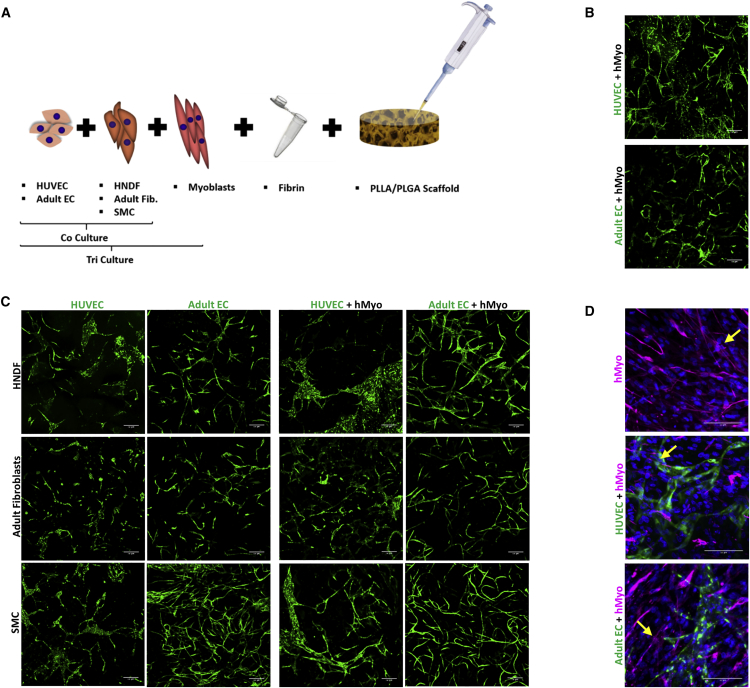

Various cell combinations were seeded on PLLA/PLGA scaffolds to compare vessel and vessel network development by adult versus umbilical vein endothelial cells in the presence of adult versus young supporting cells or mature SMCs (Figure 1A). Confocal images of the resulting constructs were captured 14 days post-seeding; representative images are presented in Figures 1B and 1C. Both HUVECs and adult ECs generated branched networks when co-cultured with HNDFs, adult dermal fibroblasts, or SMCs (Figure 1C). When seeded with desmin-positive myoblasts (Figure S1) only, both HUVEC-GFP and adult EC-ZsGreen (Figure 1B) formed vessel networks as well. The various tri-cultures containing HUVEC-GFP or adult EC-ZsGreen yielded branched networks that appeared more developed and complex compared to those in the co-culture constructs (Figure 1C). We next examined the morphology and alignment of the myoblasts, to assess their myotube-forming capacities when cultured in tri-cultures with adult ECs versus HUVECs and supporting cells. After 14 days in culture, both HUVECs and adult ECs formed vessel networks surrounded by human myoblasts. Some of the myoblasts detected using an anti-human desmin antibody differentiated to multinucleated myotubes and were semi-aligned (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Multicellular Culturing Strategy

(A) A schematic presentation of the different multicellular cultures examined: co-culture of ECs, from different origins (HUVEC-GFP/adult EC-ZsGreen), with SMCs or fibroblasts, from different origins (adult fibroblasts/HNDF), were cultured to generate 3D vascular networks. Tri-cultures comprised of ECs (HUVEC-GFP or adult EC-ZsGreen), SMCs, or fibroblasts (adult fibroblasts or NHDF) and human myoblasts, were cultured to generate 3D vascular networks within skeletal muscle constructs. (B) Representative confocal images of cultures containing either HUVEC-GFP or adult EC-ZsGreen (indicated in green), cultured with human myoblasts. Scale bar, 200 μm. (C) Representative confocal images of scaffolds populated with different cell combinations, imaged 14 days post-seeding. ECs (HUVEC-GFP/adult EC-ZsGreen) are indicated in green. Scale bar, 200 μm. (D) Representative confocal images of whole-mount immunofluorescent scaffolds populated with myoblasts alone or with human ECs (HUVEC-GFP/adult EC-ZsGreen). ECs are stained in green, desmin-positive cells are stained in magenta, and nuclei are stained in blue. Scale bar, 100 μm. Fused myoblasts are indicated by an arrow.

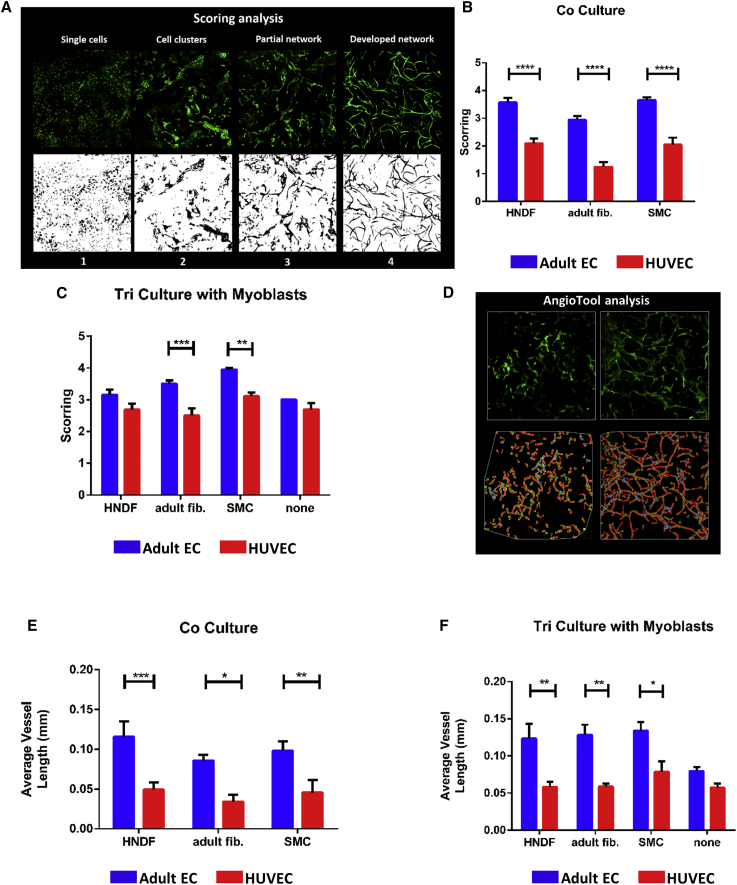

Analysis of z stacked confocal projection images showed that all tested co-culture combinations containing adult ECs showed significantly higher network complexity than co-culture combinations including HUVECs (Figures 2A and 2B). Networks formed by tri-cultures containing adult ECs with adult fibroblasts or with SMCs were significantly more complex than those formed by HUVEC-containing tri-cultures with the same supporting cells (Figure 2C). No significant differences in vessel complexity were observed in cultures containing either type of ECs and myoblasts with no additional supporting cells (Figure 2C). Vessel complexity scores were equally high in adult EC-containing tri-cultures (Figure S2A) and co-cultures. In contrast, addition of myoblasts to HUVECs co-cultured with adult fibroblasts or SMCs resulted in a significant increase in the vessel development score (Figure S2B). In summary, adult ECs supported by adult fibroblasts or adult SMCs generated more developed vessel networks as compared to the other cell combinations tested. When assessing vessel length as an indicator of network development and complexity, both adult EC co- and tri-cultures with any type of supporting cells showed a significantly longer average vessel length compared to the counterpart groups containing HUVECs (Figures 2D–2F). The only significant differences in average length of vessels formed from adult ECs was observed between co- versus tri-cultures containing adult fibroblasts (Figure S2C). Average length of vessels formed by HUVECs cultured with SMCs and myoblasts was significantly greater than any other HUVEC-containing combination (Figure S2D). When grown with myoblasts only, the average vessel length in HUVEC and adult EC cultures was similar. Of note, average vessel length in co- and tri-cultures of adult ECs isolated from two different donors was comparable (Figure S2E).

Figure 2.

In Vitro Vessel Network Development and Complexity

(A) Illustration of the scoring analysis performed to assess vessel network development. Developmental stages were scored from 1 (single cells) to 4 (fully developed network). (B) Co-culture vessel development scores are presented as means ± SEM. (C) Tri-culture vessel development scores, presented as means ± SEM. (D) Representative images of vessel networks of different complexities and their respective AngioTool analysis. Vessel skeletons are seen in red, vessel borders in yellow and vessel junctions in blue. (E) Average vessel length (±SEM) in scaffolds seeded with co-cultures. (F) Average vessel length (±SEM) in scaffolds seeded with tri-cultures. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests, n ≥ 3 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Cytokine Secretion Profile as an Indicator of EC Vasculogenic Potential

In order to determine whether differences in the vasculogenic potential of the various cultures could be predicted by cytokines expression profiles, levels of 21 secreted cytokines were quantified. Clustering in the heatmap (Figures 3A and S3A) and the Pvclust dendrogram (Figure S3B) demonstrated that the cell combinations could be divided into three statistically distinct clusters, as indicated by approximately unbiased (AU) p values >95: (1) adult ECs co-cultured with either adult fibroblasts or adult SMCs, (2) adult ECs tri-cultured with myoblasts and supported by either HNDF, SMC, or adult fibroblasts, and (3) all co- and tri-cultures containing HUVECs and the adult EC-HNDF co-culture. Furthermore, four sub-clusters, each with a distinct cytokine secretion profile, were noted: (1) tri-culture of adult ECs with HNDFs and adult fibroblasts, (2) tri-culture of HUVECs with SMCs and adult fibroblasts, (3) co- and tri-cultures containing HUVECs and HNDFs, and (4) co-cultures of HUVECs with either SMCs or adult fibroblasts (Figure S3B). Comparison of the cytokine profiles of both co- and tri-cultures containing HUVEC versus adult ECs (Figure S4B; Tables S1 and S2), revealed that key proangiogenic cytokines were expressed at significantly higher levels in cultures containing adult ECs, as compared to HUVEC groups (Figure 3B; Table S2). hVEGF, one of the most central proangiogenic factors, was expressed at significantly higher levels in tri-cultures containing adult ECs versus HUVECs; no significant difference was noted between co-culture groups. Similar differences were observed between groups containing adult ECs versus HUVECs, in their expression levels of hCSF3, a cytokine that induces VEGF release. Similarly, the proangiogenic growth factor hFGF2 was expressed at significantly higher levels in most co- and tri-cultures containing adult ECs, as compared to HUVEC groups. Cell combinations containing HUVECs displayed significantly higher expression of hANGPT2, a cytokine that mediates the early stages of angiogenesis and that is secreted at lower levels from stable blood vessels, suggesting that the associated vessel networks were not yet as stable and mature as those created by adult ECs.

Figure 3.

Cytokines, Chemokines, and Growth Hormones Secretion Analysis

(A) Expression heatmap of 21 cytokines presented by shades of gray, blue, and red. Medium was collected 14 days post-seeding and cytokine levels were estimated using the Q-Plex array chemiluminescence assay. Tested groups were categorized by EC origin, co/tri-culture, and type of supporting cells. Clustering of both the cytokines and the tested groups were performed. (B) Mean expression fold-change (±SEM) of major proangiogenic cytokines: hVEGF, hCSF3, hFGF2, and hANGPT2. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests, n ≥ 4 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Engineered Graft Transplantation, Survival, and Anastomosis In Vivo

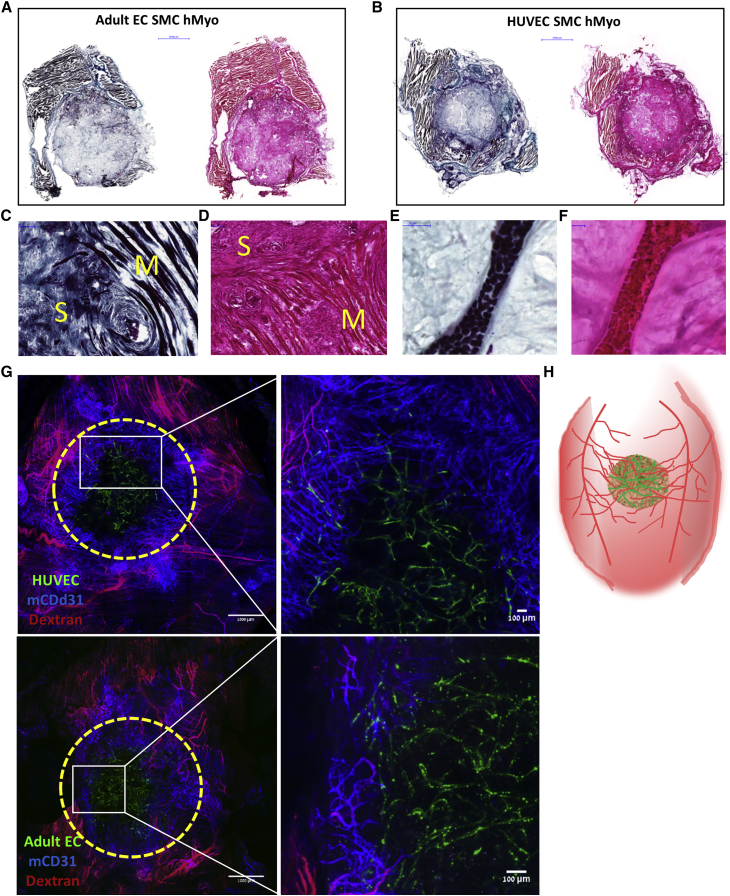

To determine the fate of the vascularized constructs in vivo, HUVEC-GFP or adult EC-ZsGreen were cultured with SMCs and human myoblasts for 14 days and then implanted into an abdominal wall defect in nude mice. The tri-culture constructs containing either HUVECs or adult ECs proved viable and were well-integrated with the host tissue 9 days post-transplantation, as indicated by the infiltration of fibro-collagenous tissue and newly formed skeletal muscle and blood vessels within the scaffold area (Figure 4). H&E and Masson trichrome staining revealed that the engineered grafts were tightly connected to the host muscle surrounding the grafts, with minimal gaps between them. In addition, collagen fibers were observed inside and around the implanted graft, suggesting the formation of new connective tissue and tissue remodeling. By 9 days post-implantation, most of the ECs along the perimeter of the grafts disappeared and were replaced by host vasculature (Figure 4G). The remaining implanted ECs were situated in the middle of the graft and occupied approximately one third of the original graft area. Most of the host vessels near the implant area did not contain rhodamine dextran, however, this can be due to its high leakiness from blood vessels, especially following graft retrieval. High magnification images of the grafts showed three types of anastomosis in both graft types: end-to-end anastomosis (Figures 5A, 5B, 5D, 5F, and 5G), host ECs enveloping the implanted ECs (Figures 5G and 5H), and implanted ECs enveloping the host ECs (Figures 5C–5E), some of which were functional, as demonstrated by the presence of rhodamine dextran in the “chimeric” vessels. Furthermore, GFP fluorescence signals and bright-field images clearly captured the presence of engineered human blood vessels that contained erythrocytes (Figure S5A). Average vessel length of the two implant types was similar (Figures 6A and 6B).

Figure 4.

Representative Ex Vivo Graft Images

(A and B) Representative images of H&E- and Masson trichrome-stained grafts populated with either adult ECs (A) or HUVECs (B), SMC and hMyo, retrieved 9 days post-implantation. Scale bar, 2,000 μm. (C and D) Representative large magnification of H&E-stained (C) and Masson trichrome-stained (D) samples from the integration area. S, scaffold; M, native mouse muscle tissue. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E and F) Representative large magnification of H&E-stained (E) and Masson trichrome-stained (F) functional blood vessel containing erythrocytes in the center of the implanted scaffold. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G) Representative images of live ex-vivo grafts populated with either HUVECs or adult ECs with SMC and hMyo, 9 days post-implantation. The scaffolds were grown for 14 days prior to implantation. Area of the implanted grafts is indicated by dashed line. Green, human ECs; red, tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated dextran; blue, mouse CD31. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) A schematic illustration of an engineered vascularized muscle tissue implanted into fill a full-thickness defect in the abdominal wall of a nude mouse.

Figure 5.

Anastomosis between Host and Graft Vasculature

(A–D) Representative ex vivo images of live grafts populated with either HUVECs or adult ECs, SMCs and hMyo, 9 days post-implantation. The scaffolds were grown for 14 days prior to implantation. Green, human ECs; red, tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated dextran; blue, mouse CD31. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E–H) Representative images of 5-μm cryosections of grafts populated with either HUVECs or adult ECs, SMCs and hMyo, 9 days post-implantation. The scaffolds were grown for 14 days prior to implantation. Green, human ECs; orange, host ECs. Scale bar, 20 μm. Yellow arrows indicate end-to-end anastomosis and circles indicate enveloping anastomosis. Functional “chimeric” vessels are indicated by a red arrow.

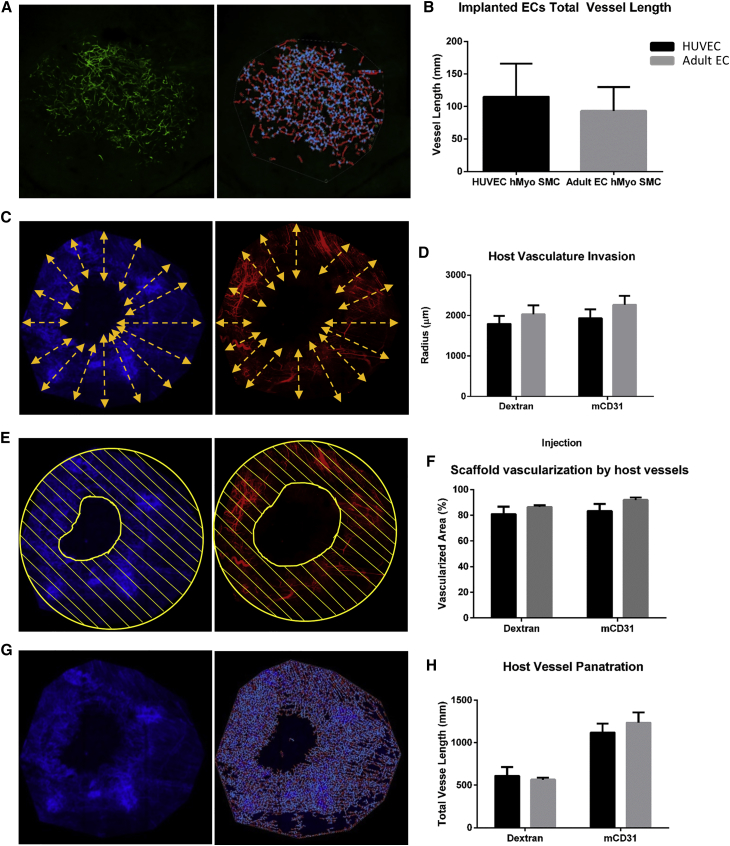

Figure 6.

Host Vasculature and Engineered Vessel Length

(A and B) AngioTool-quantitated total vessel length of implanted networks. (C and D) Invasion length of host vasculature. (E and F) Area of host vasculature within the implanted graft. (G and H) AngioTool-quantitated total vessel length of mouse vessel networks.

Graft Neovascularization

Confocal microscopy performed 9 days after transplantation demonstrated that host vasculature penetrated deep into both graft types (Figure 6), to a mean invasion radius of 2 mm (Figures 6C and 6D), vascularizing >80% of the transplanted graft (Figures 6E and 6F), with no significant difference between the two groups. Total vessel length was >1 cm, with no significant differences noted between graft types (Figures 6G and 6H). Furthermore, blood perfusion imaging conducted 7 days post-implantation revealed that the graft area was highly perfused, with no significant differences between HUVEC and adult EC tri-culture grafts (Figure S6).

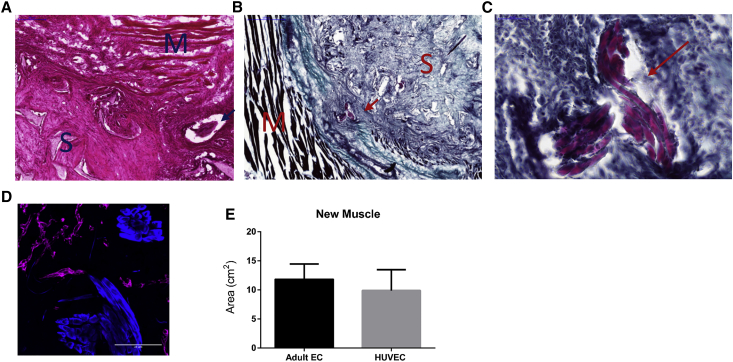

New Muscle Formation In Vivo

Young muscle fibers were observed within 9 days of transplantation of either graft type (Figure 7), indicating successful regeneration of the skeletal muscle tissue. The newly formed muscle bundles were spread both around and inside the graft area (Figures 7A–7C). Quantification of desmin signals (Figures 7D and 7E) showed no significant differences between grafts containing HUVECs versus those with adult ECs.

Figure 7.

New Muscle Formation In Vivo

(A–C) Representative images of H&E-stained (A) and Masson trichrome-stained scaffolds (B and C). S, scaffold; M, native mouse muscle tissue. Newly formed muscle bundles are indicated by an arrow. (D) Representative immunofluorescent signals in 5-μm cryosections. Blue, desmin-positive staining; magenta, mouse CD31-positive staining. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Myofiber area quantification, as determined by desmin staining analyzed using FIJI software. Data are expressed as means ± SEM, n ≥ 3.

Discussion

Tissue vascularization is a fundamental factor to address when attempting to implement tissue engineering in the clinic. In this study, we showed that fully differentiated adult ECs, isolated from the limb veins of patients with coronary artery disease, formed a complex vascular network when co-seeded for 7 days with supporting cells on 3D PLLA/PLGA biodegradable polymer scaffolds in vitro. Moreover, when adding human myoblasts, a vascular engineered muscle tissue was generated, containing both aligned myoblasts and a complex vascular network. This work also established that co-cultures and tri-cultures containing adult ECs generated more developed and complex vessel networks when compared to similar cell combinations with HUVECs. Most importantly, we demonstrated that the vascularized engineered muscle tissue was viable and integrated both with the host muscle and with the host vasculature within 9 days of implantation into a full-thickness defect in nude mouse musculature. These findings can be translated toward formation of various types of vascularized engineered tissue constructs such as muscle, bone, pancreas, liver, and cardiac tissue.

Previous studies have demonstrated that venous-derived ECs, such as HUVECs and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs), form vessel networks in vitro and integrate with the host vasculature in vivo.4, 9, 10, 11, 18 However, these cells are of lower clinical relevance for autologous treatment of adults, as they are isolated from newborn umbilical veins and foreskins, respectively, and are not suitable for clinical use in adult patients. In contrast, human adipose microvascular endothelial cells (HAMECs) are more clinically relevant and possess angiogenic and vasculogenic capacities,19 yet their isolation requires a long purification process.20 Alternatively, as demonstrated in this study, ECs isolated by a minimally invasive vein stripping procedure constitute a source of autologous ECs that can be utilized to construct a transplantable vascularized engineered tissue. PLLA/PLGA 3D synthetic scaffolds together with fibrin, have shown to actively support HUVEC-based vascularization in vitro and in vivo.4, 6, 9 Previous studies have established the biocompatibility of PLLA/PLGA porous scaffolds and estimated their degradation time to 6 months,21 ample time for the newly formed tissue to properly assemble while receiving sufficient mechanical support.

Much research has been invested in the field of muscle tissue engineering, however, most bio-artificial muscle constructs consist of aligned myofibers without vessel networks.16, 22, 23 Vascularization of large muscle constructs presents a significant leap forward in the tissue engineering field, yet is still faced with significant challenges. Native muscle tissue mimics can be constructed by co-culturing ECs with myoblasts,4, 6, 9, 24, 25 yet, when integrating human ECs and murine myoblast-like C2C12 mouse myoblasts, long and complex vessel-like structures within the myoblasts were not observed. Gholobova et al.15 recently described an engineered muscle tissue consisting of aligned human myofibers and human ECs. However, in their construct, they utilized HUVECs and a fibrin gel, which suffers from massive deformation and very rapid degradation, rendering the construct less suitable for clinical tissue engineering application. Moreover, these constructs remain to be tested in vivo.

The current study demonstrated the in vitro vasculogenic potential of adult venous ECs, which can be isolated from the arm in a minimally invasive procedure. Our previous work established the essentiality of supporting cells in the development of vessel networks in vitro and demonstrated the formation of a complex and stable vessel network in a co-culture of HUVECs and HNDFs.4, 19, 26 However, because use of HUVECs is less applicable in the clinic, we aimed to develop a new model integrating autologous ECs that can be isolated using a relatively easy and reproducible method. Tri-cultures with myoblasts were used as a proof of concept in order to demonstrate that vessel networks can also form within skeletal muscle. Indeed, vessel networks were observed in all tested groups 14 days post-seeding on PLLA/PLGA scaffolds. Nevertheless, co- and tri-cultures with adult ECs formed significantly superior networks in terms of average vessel length and maturity, as compared to HUVEC cultures (Figures 2 and S2).

Further evidence of the enhanced vasculogenic potential of adult ECs was provided by the distinct angiogenic cytokine and chemokine profiles of cell combinations containing adult ECs versus HUVECs (Figures 3, S3, and S4). More specifically, levels of secreted major proangiogenic cytokines were significantly higher in adult EC groups compared to HUVEC groups. VEGF, a key player in angiogenesis, EC sprouting, and in maintenance of the quiescent phalanx resolution,27, 28 is secreted by ECs, skeletal myoblasts, and fibroblasts.27, 29 In the tested setup, its expression levels were significantly higher in adult EC versus HUVEC cultures. This observation may account for the superior vasculogenic potential of adult ECs in vitro (Figure 3B; Table S1). hCSF3 (also known as CSF3), which is expressed by ECs and fibroblasts, induces VEGF release and promotes neovascularization.30 Indeed, hCSF3 levels detected in our experimental setup correlated with hVEGF expression profiles, with distinct differences between adult EC and HUVEC cultures. Similarly, hFGF2, a cytokine involved in the early stages of angiogenesis, as well as in the quiescent phalanx resolution,27, 28 was expressed at higher levels in cell combinations containing adult ECs versus HUVECs (Figure 3B; Table S1). hANGPT2, another major EC-expressed proangiogenic cytokine, which stimulates EC migration and sprouting in the presence of VEGF,31 is involved in early stages of angiogenesis but not in the quiescent phalanx resolution.27, 28 Its absence in cultures bearing mature vessels was therefore not surprising. hANGPT2 expression levels were significantly higher in HUEVC co- and tri-cultures compared to adult EC cultures (Figure 3B; Table S1), indicating that adult ECs form more mature and stable vessel networks as compared to those formed in vitro by HUVECs.

A common in vivo model was used to study graft integration and anastomosis with the native rectus abdominis muscle in immunodeficient mice. As a control, HUVEC-containing tri-culture grafts were tested, since our previous experiments have shown that tri-culture grafts of HUVECs, HNDFs, and mouse C2C12 myoblasts integrated well upon implantation to mice.4, 9 The present study demonstrated good integration of the adult EC grafts within the host tissue (Figure 4). Although adult EC tri-cultures showed superior vasculogenic potential in vitro, as compared to HUVEC tri-cultures, no significant difference was observed in vivo at the tested time point. We also noted the formation of many new muscle bundles within both types of implanted grafts, as early as 9 days post-implantation, indicating the early stages of mature muscle formation (Figure 7). Little is known about the anastomosis process between the host vasculature and the implanted vascular networks. One of the proposed mechanisms is wrapping-and-tapping (WAT) anastomosis described by Cheng at al.10 In their model, implanted ECs wrap around host vessels and eventually replace them. In the present study, such wrapping of the implanted ECs around the host vasculature was observed (Figure 5). In parallel, wrapping of the implanted ECs by host ECs was also detected, albeit, less frequently (Figure 5). Vessel-to-vessel anastomosis was most commonly observed (Figure 5). Moreover, GFP fluorescence signals and bright-field images of the implanted vessel networks clearly showed erythrocytes inside the vessels (Figure S5), suggesting that they were perfused and functional. Blood perfusion analysis also demonstrated that the area of the graft was highly perfused, with no significant differences between HUVEC and adult EC tri-culture grafts (Figure S6).

In summary, the presented results provide strong evidence of the vasculogenic potential of adult limb veins-isolated ECs for cell therapy applications. Such cells effectively populate engineered tissues and form autologous vessel networks within. As a proof of concept, the constructed vascularized engineered human skeletal muscle grafts intimately integrated with the native muscle tissue of mice. Further efforts are still required to construct larger tissues that can be utilized in the clinic.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

HUVECs were purchased from Lonza (USA) and adult primary venous endothelial cells (adult ECs) were isolated from a lower-extremity vein segment, as previously described.17, 32, 33 Both EC types were cultured in endothelial basal growth medium-2 (EBM-2, supplemented with FGF2, IGF-1, and EGF from the EGM-2 BulletKit; Lonza). GFP expressing-HUVEC (HUVEC-GFP) (Angio-Proteomie) and ZsGreen fluorescent protein-expressing adult venous ECs were cultured in EBM-2, supplemented with the respective BulletKit and 3% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (HNDFs) were purchased from Lonza and adult human dermal fibroblasts (adult HDFs) were isolated as previously described.34 Both fibroblast cell types were cultured in DMEM (Gibco Life Technologies), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% nonessential amino acids (Biological Industries), 0.2% β-mercaptoethanol (Biological Industries), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Pen-Strep Solution, Biological Industries). Adult human venous smooth muscle cells (adult SMCs) were isolated from a lower-extremity vein segment, as previously described,17, 35 and grown in DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS and Pen-Strep Solution. Primary human skeletal muscle cells (SkMC) were purchased from PromoCell and cultured in the recommended PromoCell Skeletal Muscle Cell Growth Medium. All incubations were in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C.

Lentivirus Packaging and Transduction with ZsGreen Fluorescent Protein

Recombinant, replication-incompetent, VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviruses were generated using a Lenti-X HTX Packaging System (Clontech, a 4th Generation [5 vector split packaging technology and inducible promoters]). Production of the lentiviruses was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the expression vector (pLVX-ZsGreen1-C1, Clontech) was transfected, in a Lenti-X HTX Packaging Mix, into the Lenti-X 293T packaging cells (Clontech). After 72 hr, the lentiviral supernatants produced by the transfected packaging cells were filtered through a 45-μm filter to remove cellular debris and then used to transduce the target cells.

Adult ECs were seeded at a density of 5,000 cells/cm2, allowed to adhere, and then transduced with the ZsGreen lentivirus particles in the presence of 6 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). The transduction medium was replaced after 24 hr, and the cells were incubated for up to 72 hr to allow for the gene product to accumulate in the target cells. Then, selection for stably expressing cells was performed using 1 μg/mL puromycin (Takara Bio Company).

Flow Cytometry

Primary human skeletal muscle cells were grown until 70% confluence. Then, cells were trypsinized and fixated with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Fixated cells were washed and incubated with a 1:50 anti-desmin (Cell Signaling Technology) antibody solution for 60 min at RT before being thoroughly washed. Next, the cells were incubated with Alexa 647-conjugated IgG (1:400; Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 4°C. Lastly, cells were washed and stored in PBS at 4°C until flow cytometry. All washes and antibody incubations were performed in 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS in PBS. Cells were analyzed using the BD LSR-II flow cytometer (Becton Dickenson). Data acquisition of 10,000 events per sample was performed without gating. Data were analyzed using FCS Express software (De Novo Software). Human skeletal muscle cells immunolabeled with an isotype-matched negative control antibody were analyzed as a reference.

PLLA/PLGA Scaffolds

Porous sponges composed of 50% poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) (Polysciences) and 50% polylactic glycolic acid (Boehringer Ingelheim), were fabricated utilizing a particle leaching technique to achieve pore sizes of 212−600 μm and 93% porosity.4, 9 Briefly, PLLA and PLGA were dissolved 1:1 in chloroform, to yield a 5% (w/v) polymer solution; 0.24 mL of this solution was loaded into silicon rubber molds packed with 0.4 g sodium chloride particles. The solvent was allowed to evaporate overnight and the sponges were subsequently immersed for 8 hr in distilled water (changed every hour), to leach the salt and create an interconnected pore structure. The sponges were cut into circles of 6 mm diameter and 1 mm thick. Before use, sponges were soaked in 70% (v/v) ethyl alcohol overnight and washed three times with PBS. Previous works have demonstrated the biocompatibility of the PLLA/PLGA porous scaffold and an estimated 6-month degradation time.21

Multicellular Cultures

Co-culture

Endothelial cells (0.5 × 106 cells) from different origins (HUVEC/adult EC) and SMC or fibroblasts (0.1 × 106 cells) from different origins (adult HDF/NHDF) were cultured to generate 3D vascular networks.

Tri-culture

Endothelial cells (0.5 × 106 cells) from different origins (HUVEC/adult EC), SMCs or fibroblasts (0.1 × 106 cells) from different origins (adult HDF/NHDF) and human myoblasts (0.2 × 106 cells) were cultured to generate 3D vascular networks within skeletal muscle constructs.

Engineering Vascularized 3D Constructs

Cells were trypsinized at passage 6 or 7 and re-suspended in 8 μL of a 1:1 mixture of 15 mg/mL fibrinogen (Johnson & Johnson Medical) and 5 U/mL thrombin (Johnson & Johnson Medical). Each cell suspension was seeded into the scaffold and then allowed to solidify for 30 min (37°C, 5% CO2) inside a 6-well plate. After solidification, 4 mL culture medium was added to each well. Medium was replaced every other day.

Whole-Mount Immunofluorescence Staining

Scaffolds were fixated in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 20 min and subsequently washed with PBS. Cells were then permeabilized by adding 0.3% Triton X-100 (Bio Lab) for 10 min at RT. The scaffolds were then washed with PBS and immersed overnight in blocking serum (10% FBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% glycine) at 4°C. Scaffolds were then incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-desmin antibodies (clone D93F5; 1:250, Cell Signaling Technology) diluted in blocking serum. Following several washes in PBS (5–10 min each), Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000, Molecular Probes) was applied for 3 hr. Scaffolds were then washed in PBS and stored in 24-well plates in PBS at 4°C until observation under a Zeiss LSM700 inverted confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss), with 5× and 10× objective lenses, using ZEN software (Carl Zeiss). Further image analysis was conducted using FIJI (Fiji Is Just ImageJ) software.

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence Staining

Grafts retrieved 9 days post-transplantation were incubated overnight in a 30% (w/v) sucrose solution, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tec), and frozen for subsequent cryosectioning to 5-μm thick sections. For immunofluorescence staining, the sections were incubated in 0.5% Tween solution for 20 min, rinsed with PBS, and then blocked with a 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich), for an additional 30 min. The sections were then incubated in a 1:200 anti-desmin (Cell Signaling Technology) antibody solution for 30 min at RT before being thoroughly washed with PBS. The sections were then labeled with Alexa 405-conjugated IgG (1:400; Molecular Probes), mounted in Vectashield that contained DAPI (Vector Laboratories), and examined under a confocal microscope. For H&E staining, the slides were air-dried for several minutes to remove moisture and stained with filtered 0.1% Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min. Then, the slides were rinsed with tap water and stained with 0.5% Eosin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 min. Next, the slides were dipped in double distilled water (DDW) and dehydrated by serial immersions in increasing concentrations of ethanol. Finally, slides were dipped in xylene and covered with Vectamount (Vector Labs). For Masson trichrome staining, the slides were air-dried for several minutes to remove moisture and stained with filtered 0.1% Mayers hematoxylin for 5 min. Then, the slides were rinsed with distilled water and stained with trichrome stain (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 min. Next, the slides were washed twice in 0.2% glacial acetic acid and then in DDW. Afterward, the slides were dehydrated by serial immersions in increasing concentrations of ethanol and finally dipped in xylene and covered with Vectamount. Slides were imaged using the Pannoramic MIDI automatic digital slide scanner (3DHISTECH). Images were analyzed with the Pannoramic Viewer software (3DHISTECH).

Vessel Network Development Determination

HUVEC-GFP and adult EC-ZsGreen were imaged, with a confocal microscope, 14 days post-seeding. Vessel network development in each construct was scored on a 4-point scale by an independent expert blinded to the culture components. Scaffolds containing isolated ECs were scored 1. Constructs that exhibited cell clusters were scored 2 and when there was a partial network within the constructs, they were scored 3. Scaffolds with a fully developed network received the highest score of 4. Half scores were also applied and a minimum of five constructs per tested cell combination were analyzed in two independent experiments. The construct scores were averaged and SEM mean was calculated.

Vessel Length Quantification

Average and total length (mm) of vessels within the constructs, as observed 14 days post-seeding, were calculated by analyzing z stack confocal projection images, using the AngioTool software (AngioTool).36 Longer vessel lengths were considered indicative of a more developed and complex network. A minimum of five constructs per tested cell combination were analyzed in two independent experiments.

Cytokines, Chemokines, and Growth Hormone Secretion Array and Analysis

The expression levels of 21 cytokines, chemokines, and hormones secreted by the cells were analyzed from the culture media of the studied cell combinations. The tested factors were: interleukin 15 (hIL15), angiopoietin 2 (hANGPT2), chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 5 (hCXCL5), basic fibroblast growth factor (hFGF2), hfractalkine, colony stimulating factor 3 (hCSF3), colony stimulating factor 2 (hCSF2), chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 1 (hCXCL1), hepatocyte growth factor (hHGF), interleukin 1, beta (hIL1b), chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 8 (hCXCL8), interleukin 6 (hIL6), chemokine (C-C Motif) ligand 2 (hCCL2), chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 9 (hCXCL9), chemokine (C-C Motif) ligand 4 (hCCL4), platelet-derived growth factor (hPDGF), platelet factor 4 (hPF4), chemokine (C-C Motif) ligand 1(hCCL1), TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 2 (hTIMP2), tumor necrosis factor (hTNFa), and vascular endothelial growth factor A (hVEGF). For this purpose, a custom-made multiplexed ELISA kit, called Q-Plex (Quansys Biosciences) was used. Growth medium without cultured cells was used as a control. For cytokine concentration analysis, measured values of each cytokine were divided by the average value of that cytokine measured in the growth medium with no cells. For heatmap analysis, raw data were logarithmically transformed and control values were subtracted. All the statistical testing and visualization were performed by R—a programming language and software environment for statistical computing and graphics. Hierarchical clustering with a complete linkage was performed and visualized using the “pheatmap” package of R language (version 1.0.7) with the following parameters: cluster_col = TRUE, cutree_row = 4, cutree_col = 4. To simplify heatmap visualization, the 14 cell combinations were divided into three levels and colored-coded: EC origin (HUVEC/Adult EC), culture type (Myo and Co/Tri with Myo), and supporting cell (HNDF/Adult Fibroblasts/SMC/None). Negative log transformation values are represented in gray, low values in dark blue, medium values in light blue, and high values in red (Figures 3A and S3A). The significance of hierarchical clustering was assessed using the “pvclust” R-package, where AU scores ≥95 indicated statistically significant branching.37

Transplantation of the Engineered Tissue

All surgical procedures were conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Technion IIT. Tri-cultures of HUVEC-GFP, SMC, and hMyo (n = 4) and of adult EC-ZsGreen, SMC and hMyo (n = 3), were cultured on PLLA/PLGA scaffolds for 14 days in vitro and then implanted into mice. Male, nude, 9-week-old mice (Harlan Laboratories) were anesthetized via intra-peritoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine-xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively), using a 30-gauge needle. Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was subcutaneously injected 20 min before the procedure and every 12 hr thereafter for 3 days. The planned incision site was cleaned with alcohol and iodine to establish an aseptic working field. Then, an incision was made in the ventral skin and the abdominal wall was exposed. Next, a 6- mm diameter full-thickness segment of the rectus abdominis muscle was removed and replaced with engineered skeletal muscle, secured with 8-0 polypropylene sutures. The skin was then closed over the replaced abdominal tissue and sutured using 4-0 silk sutures. All mice were closely monitored for 1–2 hr to ensure full recovery from the anesthesia.

Blood Perfusion Imaging

A 13-mm diameter abdominal window was placed on top of the graft and secured using a purse-string suture. Mice were anesthetized and blood perfusion within the grafts was assessed using the moor FLPI-2 laser speckle blood flow imager (Moor Instruments).

Imaging of Retrieved Grafts

Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD31 antibody (mCD31-X647; Biolegend) (0.5 mg/mL) was intravenously injected into the tail vein 9 days post-implantation and allowed to circulate for ∼15 min. Then, the mice were anesthetized (using ketamine-xylazine as described above) and tetramethyl rhodamineisothiocyanate-dextran (10 mg/mL) (average MW 155,000, Sigma-Aldrich) was intravenously injected into the tail vein and allowed to perfuse for 20 s before euthanization. Then, the grafts were retrieved, fixed in 10% formalin (Sigma-Aldrich), and visualized using an LSM700 confocal microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Group differences were determined by a two-tailed Student’s t test. Where appropriate, data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni or Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. P values below 0.05 were taken to indicate a statistically significant difference between groups. Statistical analyses were performed using a computerized statistical program (GraphPad Software). Differences in cytokine levels were measured using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn multiple comparison test.

Author Contributions

L.P. designed the research program, performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.Y.F. contributed to the study design and manuscript editing and provided adult ECs and SMCs. S.L. served as principal investigator and contributed to the conceptual idea for the paper, experimental design, critical suggestions, and writing and editing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janette Zavin for her assistance with the cryosectioning, Dr. Inbal Michael for assistance with viral transfection, Dr. Michael Shmoish for assistance with the cytokine analysis, and Dr. Yehudit Posen for editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript. This work was supported by funding from the FP7 European Research Council (grant 281501, ENGVASC).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes six figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.011.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Novosel E.C., Kleinhans C., Kluger P.J. Vascularization is the key challenge in tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouwkema J., Rivron N.C., van Blitterswijk C.A. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auger F.A., Gibot L., Lacroix D. The pivotal role of vascularization in tissue engineering. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2013;15:177–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesman A., Koffler J., Atlas R., Blinder Y.J., Kam Z., Levenberg S. Engineering vessel-like networks within multicellular fibrin-based constructs. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7856–7869. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levenberg S., Rouwkema J., Macdonald M., Garfein E.S., Kohane D.S., Darland D.C., Marini R., van Blitterswijk C.A., Mulligan R.C., D’Amore P.A., Langer R. Engineering vascularized skeletal muscle tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shandalov Y., Egozi D., Koffler J., Dado-Rosenfeld D., Ben-Shimol D., Freiman A., Shor E., Kabala A., Levenberg S. An engineered muscle flap for reconstruction of large soft tissue defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6010–6015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402679111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koike N., Fukumura D., Gralla O., Au P., Schechner J.S., Jain R.K. Tissue engineering: creation of long-lasting blood vessels. Nature. 2004;428:138–139. doi: 10.1038/428138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen T.O., Blois A.L., Xue Y., Xing Z., Sun Y., Finne-Wistrand A., Lorens J.B., Fristad I., Leknes K.N., Mustafa K. Mesenchymal stem cells induce endothelial cell quiescence and promote capillary formation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014;5:23. doi: 10.1186/scrt412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koffler J., Kaufman-Francis K., Shandalov Y., Egozi D., Pavlov D.A., Landesberg A., Levenberg S. Improved vascular organization enhances functional integration of engineered skeletal muscle grafts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14789–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017825108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng G., Liao S., Kit Wong H., Lacorre D.A., di Tomaso E., Au P., Fukumura D., Jain R.K., Munn L.L. Engineered blood vessel networks connect to host vasculature via wrapping-and-tapping anastomosis. Blood. 2011;118:4740–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X., Aledia A.S., Popson S.A., Him L., Hughes C.C., George S.C. Rapid anastomosis of endothelial progenitor cell-derived vessels with host vasculature is promoted by a high density of cotransplanted fibroblasts. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2010;16:585–594. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klumpp D., Horch R.E., Kneser U., Beier J.P. Engineering skeletal muscle tissue--new perspectives in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010;14:2622–2629. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bach A.D., Beier J.P., Stern-Staeter J., Horch R.E. Skeletal muscle tissue engineering. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2004;8:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bach A.D., Arkudas A., Tjiawi J., Polykandriotis E., Kneser U., Horch R.E., Beier J.P. A new approach to tissue engineering of vascularized skeletal muscle. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006;10:716–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gholobova D., Decroix L., Van Muylder V., Desender L., Gerard M., Carpentier G., Vandenburgh H., Thorrez L. Endothelial network formation within human tissue-engineered skeletal muscle. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2015;21:2548–2558. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhas M., Engelmayr G.C., Jr., Fontanella A.N., Palmer G.M., Bursac N. Biomimetic engineered muscle with capacity for vascular integration and functional maturation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:5508–5513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman P.M., Mohler E.R., 3rd, Roessler B.J., Wilensky R.L., Levine B.L., Woo E.Y., Upchurch G.R., Jr., Schneiderman J., Koren B., Hutoran M. Phase I study of multi-gene cell therapy in patients with peripheral artery disease. Vasc. Med. 2016;21:21–32. doi: 10.1177/1358863X15612148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melero-Martin J.M., Khan Z.A., Picard A., Wu X., Paruchuri S., Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109:4761–4768. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freiman A., Shandalov Y., Rozenfeld D., Shor E., Segal S., Ben-David D., Meretzki S., Egozi D., Levenberg S. Adipose-derived endothelial and mesenchymal stem cells enhance vascular network formation on three-dimensional constructs in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016;7:5. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser J.K., Wulur I., Alfonso Z., Hedrick M.H. Fat tissue: an underappreciated source of stem cells for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holder W.D., Jr., Gruber H.E., Moore A.L., Culberson C.R., Anderson W., Burg K.J., Mooney D.J. Cellular ingrowth and thickness changes in poly-L-lactide and polyglycolide matrices implanted subcutaneously in the rat. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998;41:412–421. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980905)41:3<412::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorrez L., Vandenburgh H., Callewaert N., Mertens N., Shansky J., Wang L., Arnout J., Collen D., Chuah M., Vandendriessche T. Angiogenesis enhances factor IX delivery and persistence from retrievable human bioengineered muscle implants. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee P.H., Vandenburgh H.H. Skeletal muscle atrophy in bioengineered skeletal muscle: a new model system. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2013;19:2147–2155. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Criswell T.L., Corona B.T., Wang Z., Zhou Y., Niu G., Xu Y., Christ G.J., Soker S. The role of endothelial cells in myofiber differentiation and the vascularization and innervation of bioengineered muscle tissue in vivo. Biomaterials. 2013;34:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenfeld D., Landau S., Shandalov Y., Raindel N., Freiman A., Shor E., Blinder Y., Vandenburgh H.H., Mooney D.J., Levenberg S. Morphogenesis of 3D vascular networks is regulated by tensile forces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:3215–3220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522273113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blinder Y.J., Freiman A., Raindel N., Mooney D.J., Levenberg S. Vasculogenic dynamics in 3D engineered tissue constructs. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17840. doi: 10.1038/srep17840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welti J., Loges S., Dimmeler S., Carmeliet P. Recent molecular discoveries in angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapies in cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3190–3200. doi: 10.1172/JCI70212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmeliet P., Jain R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrne A.M., Bouchier-Hayes D.J., Harmey J.H. Angiogenic and cell survival functions of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2005;9:777–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kameyama H., Udagawa O., Hoshi T., Toukairin Y., Arai T., Nogami M. The mRNA expressions and immunohistochemistry of factors involved in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the early stage of rat skin incision wounds. Leg. Med. (Tokyo) 2015;17:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felcht M., Luck R., Schering A., Seidel P., Srivastava K., Hu J., Bartol A., Kienast Y., Vettel C., Loos E.K. Angiopoietin-2 differentially regulates angiogenesis through TIE2 and integrin signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:1991–2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI58832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gluzman Z., Koren B., Preis M., Cohen T., Tsaba A., Cosset F.L., Shofti R., Lewis B.S., Virmani R., Flugelman M.Y. Endothelial cells are activated by angiopoeitin-1 gene transfer and produce coordinated sprouting in vitro and arteriogenesis in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;359:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flugelman M.Y., Virmani R., Leon M.B., Bowman R.L., Dichek D.A. Genetically engineered endothelial cells remain adherent and viable after stent deployment and exposure to flow in vitro. Circ. Res. 1992;70:348–354. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furie N., Shteynberg D., Elkhatib R., Perry L., Ullmann Y., Feferman Y., Preis M., Flugelman M.Y., Tzchori I. Fibulin-5 regulates keloid-derived fibroblast-like cells through integrin beta-1. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2016;38:35–40. doi: 10.1111/ics.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preis M., Schneiderman J., Koren B., Ben-Yosef Y., Levin-Ashkenazi D., Shapiro S., Cohen T., Blich M., Israeli-Amit M., Sarnatzki Y. Co-expression of fibulin-5 and VEGF165 increases long-term patency of synthetic vascular grafts seeded with autologous endothelial cells. Gene Ther. 2016;23:237–246. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zudaire E., Gambardella L., Kurcz C., Vermeren S. A computational tool for quantitative analysis of vascular networks. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki R., Shimodaira H. Pvclust: an R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1540–1542. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.