Abstract

Background

Shoot regeneration frequency in rice callus is still low and highly diverse among rice cultivars. This study aimed to investigate the association of plant hormone signaling and sucrose uptake and metabolism in rice during callus induction and early shoot organogenesis. The immatured seeds of two rice cultivars, Ai-Nan-Tsao 39 (ANT39) and Tainan 11 (TN11) are used in this study.

Results

Callus formation is earlier, callus fresh weight is higher, but water content is significant lower in ANT39 than in TN11 while their explants are inoculated on callus induction medium (CIM). Besides, the regeneration frequency is prominently higher in ANT39 (~80%) compared to TN11 callus (0%). Levels of glucose, sucrose, and starch are all significant higher in ANT39 than in TN11 either at callus induction or early shoot organogenesis stage. Moreover, high expression levels of Cell wall-bound invertase 1, Sucrose transporter 1 (OsSUT1) and OsSUT2 are detected in ANT39 at the fourth-day in CIM but it cannot be detected in TN11 until the tenth-day. It suggested that ANT39 has higher callus growth rate and shoot regeneration ability may cause from higher activity of sucrose uptake and metabolism. As well, the expression levels of ORYZA SATIVA RESPONSE REGULATOR 1 (ORR1), PIN-formed 1 and Late embryogenesis-abundant 1, representing endogenous cytokinin, auxin and ABA signals, respectively, were also up-regulated in highly regenerable callus, ANT39, but only ORR1 was greatly enhanced in TN11 at the tenth-day in CIM.

Conclusion

Thus, phytohormone signals may affect sucrose metabolism to trigger callus initiation and further de novo shoot regeneration in rice culture.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1999-3110-54-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oryza sativa, Sucrose, Shoot organogenesis, Phytohormones, Callus

Background

Totipotency ability in individual plant cells can be regenerated to a whole plant by modulating culture conditions (Reinert, 1959). Many factors influence plantlet regeneration ability; examples are genotypes (Huang et al., 2002; Glowacha et al., 2010), phytohormones (Barreto et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2010; Sun and Hong, 2010; Huang et al., 2012), osmotic requirement (Huang and Liu, 2002; Pan et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012) and carbon sources (Huang and Liu, 2002; Iraqi et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2010; Silva, 2010). However, the mechanisms of totipotency are still not clarified.

The callus differentiation pathway involves somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis (Jiménez, 2005). Previous studies indicated that both pathways generate entire plantlets from callus in rice but mainly through organogenesis (Jiang et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2012). However, shoot organogenesis from rice calli derived from immature embryo differ among varieties (Huang et al., 2002; Khaleda and Al-Forkan 2006; Dabul et al., 2009). Indica rice varieties generally are less amenable to shoot organogenesis (Zaidi et al., 2006). However, some indica rice varieties have been used to establish high-regeneration-frequency callus culture (Hoque and Mansfied 2004; Wani et al., 2011). In our previous study, the indica rice Ai-Nan-Tsao 39 (ANT39) was the only one screened from 15 cultivars to have high shoot organogenesis frequency (more than 70%) without the need for extra-osmotic stress treatment during callus induction (Huang et al., 2006).

Exogenous carbohydrates are used as the main energy source for explants because of their heterotrophism. Numerous studies have focused on the effect of the kinds and concentrations of carbohydrate supplemented into media (Iraqi et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2010; Silva, 2010); however, the metabolic pathway during callus induction and shoot organogenesis has rarely been discussed. Sucrose is generally used in plant tissue culture; explants uptake sucrose from the medium and hydrolyze it into glucose, fructose for subsequent metabolism (Amino and Tazawa, 1988; Schmitz and Lorz, 1990; Huang and Liu, 2002). Cell wall-bound invertase (CIN) and sucrose transporter (SUT) are the main routes for sucrose absorption and transportation in higher plants. In rice, CIN is involved in many physiological functions such as grain filling, early seed development and inflorescence differentiation (Hirose et al., 2002; Cho et al., 2005Ji et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Like CIN, SUT was found related to seed development, stress response, and plant growth (Scofield et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Siao et al., 2011; Siahpoosh et al., 2012). However, the effect of these sucrose metabolism-related genes on callus formation and shoot regeneration in rice are still unknown. Changes in sucrose- or starch-metabolism–related enzyme activities in callus culture were found in Gossypium hirsutum (Kavi Kishor et al., 1992), Daucus caroata (Tang et al., 1999), Medicago arborea (Cuadrado et al., 2001), and Picea mariana (Iraqi et al., 2005). In our preliminary studies, cellular starch content at callus induction and glucose content at the early regeneration stage were important factors for shoot regeneration in rice (Huang and Liu, 2002; Huang et al., 2006). However, the signals to trigger carbohydrate metabolism and gene expression of related enzymes in rice callus are still poorly understood.

Plant growth regulators (PGRs) have an important role in cell growth and differentiation. Since the classical finding of auxin and cytokinin (Skoog et al., 1965), many papers have shown the effect of PGRs in tissue culture. Both exogenous and endogenous levels of PGRs are highly related to shoot organogenesis (Yin et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012). Auxin, cytokinin, and ABA are considered key factors for shoot differentiation in callus culture (Brown et al., 1989; Pernisová et al., 2009; Su et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2010; Vanneste and Friml, 2009; Zhao et al., 2010). Our previous studies showed high levels of endogenous auxin, abscisic acid, and zeatin in highly regenerable rice callus (Liu and Lee, 1996; Huang et al., 2012). B-type response regulator (B-RR) proteins are positive signal regulators for cytokinin signaling (Müller and Sheen, 2007) and the gene expression could be recognized at the cytokinin level (Mason et al., 2005). The B-RR ORYZA SATIVA RESPONSE REGULATOR 1 (ORR1) affects cytokinin signaling in rice (Ito and Kurata, 2006). Similarly, the auxin efflux carrier gene family, PIN-formed (PINs), are a key factor for auxin polar transport (Petrásek et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009). OsPIN1 can be detected in calli (Xu et al., 2006) and is related to root emergence and tillering (Huang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2009). PIN gene expression may represent auxin accumulation (Xu et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2010). Besides, OsLEA1 is regulated by ABA and represented as the signal of endogenous ABA (Shih et al., 2010).

Many studies have shown the cross-talk between phytohormones and sugar sensing in higher plant. Glucose might be a bridge between carbohydrate and phytohormone signaling (Halford and Paul 2003; León and Sheen, 2003; Roitsch et al., 2003; Hartig and Beck, 2006). However, no reports have discussed the relationship between PGR signaling, carbohydrate metabolism, and shoot organogenesis.

In this study, we used two rice cultivars with variable regenerative ability to compare carbohydrate content and gene expression of sucrose-metabolism–related enzymes during callus induction and shoot organogenesis. We further identified the gene expression patterns of OsPIN1, ORR1 and OsLEA1 in at the same cultivation period to clarify the relationship between plant hormone signaling and sucrose metabolism in rice callus. Sucrose metabolism may be an important part of shoot organogenesis and may be triggered by phytohormones signaling.

Methods

Plant material, callus induction and shoot regeneration

Primary callus was derived from 12- to 14 day-old immature seeds of two rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.) “Tainan 11” (TN11) and “Ai-Nan-Tsao 39” (ANT39) incubated on callus induction medium (CIM) composed of MS basal medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 3% sucrose and 10 μM 2, 4-D (Huang et al., 2012). After 2 weeks, calli were transferred to regeneration medium (RM) composed of MS basal medium plus 10 μM NAA and 20 μM kinetin. Both CIM and RM were cultured at approximately 27°C and 200 μmole photons m-2 s-1 with a 12-h light/dark photoperiod. Calli were harvested at the 10th and 14th days in CIM and fresh weight was measured. Shoot regeneration frequency (%) was evaluated at week 4 after transfer to RM as (calli number with regenerated plantlets / total calli number) x 100%. The calli with regenerated plantlets higher than 1 cm were calculated. The results were from at least 3 independent experiments.

Measurements of callus growth and water content

Callus was collected on day 10 and day 14 on CIM. These collected calli were weighted as their fresh weight. Dry weights were obtained from these fresh calli that were dried in a ventilating oven at 60°C for 48 hours. Water content was determined from (Fresh weight - Dry weight / Fresh weight) × 100%. Each data was averaged from at least 5 independent calli.

Extraction and concentration determination of carbohydrates

Samples were harvested after inoculation for 4, 7, 10, 14 days in CIM and 1, 3, 5 and 7 days in RM. The samples were weighed up to 100 mg and dried in a ventilating oven at 60°C for 48 h, then extracted twice with 80% ethanol. The supernatant and pellet were used for soluble sugars (sucrose and glucose) and starch measurement, respectively (Huang and Liu, 2002). A glucose assay kit (Sigma) was used for glucose content determination. The assay solution was added to the ethanol-extracted supernatant and incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and 2 mL of 12N H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction. The absorption value of 540 nm was obtained by use of a spectrophotometer (U-2001, Hitachi). Each sample was replicated at least 3 times. For sucrose content, ethanol-extracted solution was hydrolyzed by use of invertase (Sigma) for 1 h then underwent the above glucose-content assay (Huang et al., 2006). The absorption value included both sucrose and glucose, so the glucose content was subtracted from this determination to obtain sucrose content.

The pellet was re-suspended with deionic water and boiled for 20 min for measurement of starch content. Amyloglucosidase mixture (90 mM sodium-acetate, 0.1% NaN3, and 25 units amyloglucosidase, pH 4.6) was added for incubation at 55°C for 2 h (Huang and Liu, 2002). The supernatant was collected after centrifugation and quantified as described above for glucose content measurement.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from the callus (approximately 100 mg) by the TRIzol reagent method (Invitrogen) and treated with TURBO DNA-free™ DNase (Ambion) to remove residual DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA with use of MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative RT-PCR involved the IQ2 Fast qPCR System (Bio-Genesis) on the ECO™ real-time PCR machine (Illumina). The gene-specific primers designed from the 3’UTR of rice genes are shown in Table 1. The quantitative RT-PCR program initially started with 95°C denaturation for 5 min, followed 40 cycles by 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. To quantify the relative expression of genes, 2-ΔΔCq values of the target gene were normalized to that of ubiquitin (OsUBI) gene.

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis

| Gene | Accession number | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OsCIN1 | AY578158 | TACGGCAACTTCTACGCATC | CTTGTCGTAGGTGACGCTGT |

| OsSUT1 | D87819 | TCCTCTGGTTCCACAAACAA | ATTTGCACAAGCTTCACAGC |

| OsSUT2 | AB091672 | ATTCCCGTTCACCGTTACTC | AGGATTGAGGCTCTTGCACT |

| OsPIN1 | AF056027 | AACCCGAACACCTACTCCAG | CATCTCGAAGTTCCACCTGA |

| ORR1 | AB246780 | GCCATTTGCAGAAGTTCAGA | AAGTCCTCCCAGTGAGCCTA |

| OsLEA1 | AK064055 | GACGACAAGATGCTCAAGGA | CATGCACATGGATACACCAA |

| OsUBI | D12629 | CGCAAGTACAACCAGGACAA | TGGTTGCTGTGACCACACTT |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by use of Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test with SPSS v 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Rice cultivars differ in callus growth, morphologic features and regeneration frequency

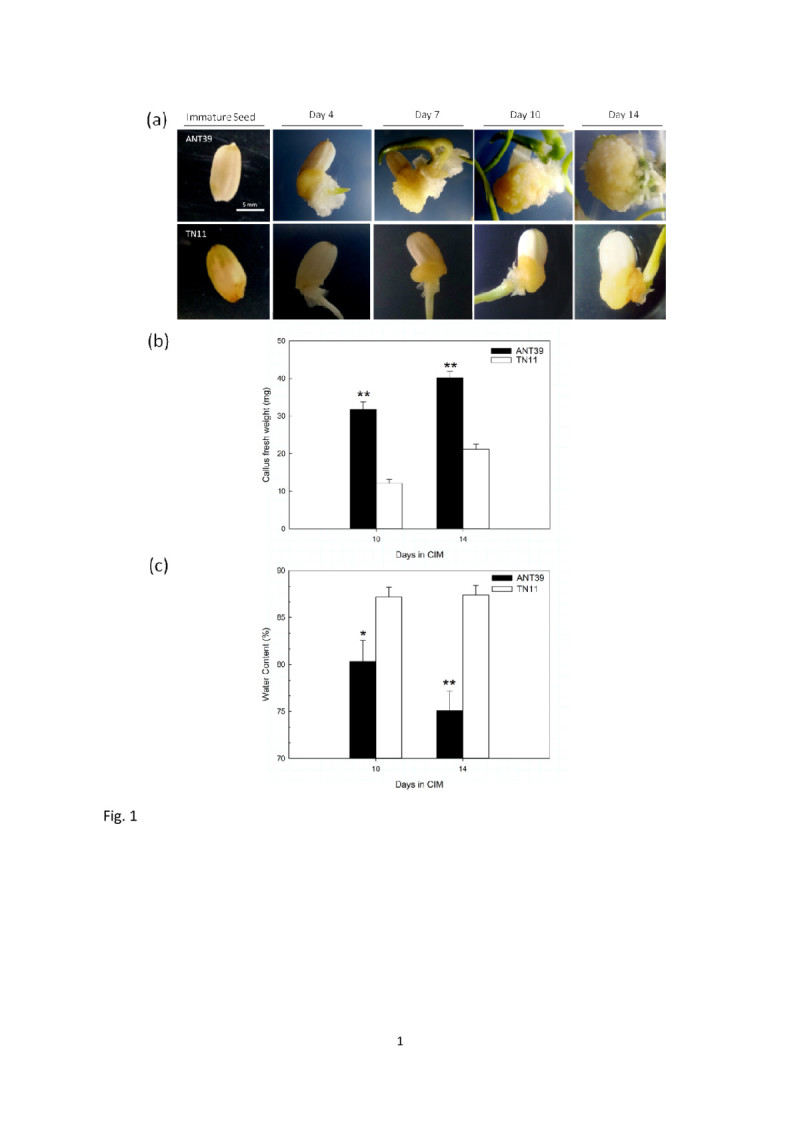

To compare the callus induction and shoot organogenic ability between two rice cultivars, we observed the callus morphology and fresh weight variation. It showed that the calli formed from ANT39 immature seed inoculated on CIM for 3 to 4 days but recognized callus clear from TN11 explant late to days 6 to 7 (Figure 1a). ANT39 calli are large, compact and whitish, but TN11 calli are small and yellowish. The fresh weight of callus was greatly increased and significantly higher in ANT39 than in TN11. The average fresh weight each callus at the fourteenth-day is approximately to 40 mg in ANT39, however, only 22 mg in TN11 at the same day (Figure 1b). On the other hand, the water content at the fourteenth-day callus in ANT39 is 75% but it is approximately to 88% in TN11 callus (Figure 1c). The results suggested ANT39 has higher callus formation ability and growth rate compared to TN11.

Figure 1.

Morphological features (a), fresh weight (b), and water content (c) of Ai-Nan-Tsao 39 (ANT39) and Tainan 11 (TN11) calli from immature seeds inoculated on MS basal media containing 3% sucrose and 10 μM 2,4-D. * and ** denote significant difference between ANT39 and TN11 based on the level of 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. Data are mean ± standard error (n=3). Scale bar = 5 mm.

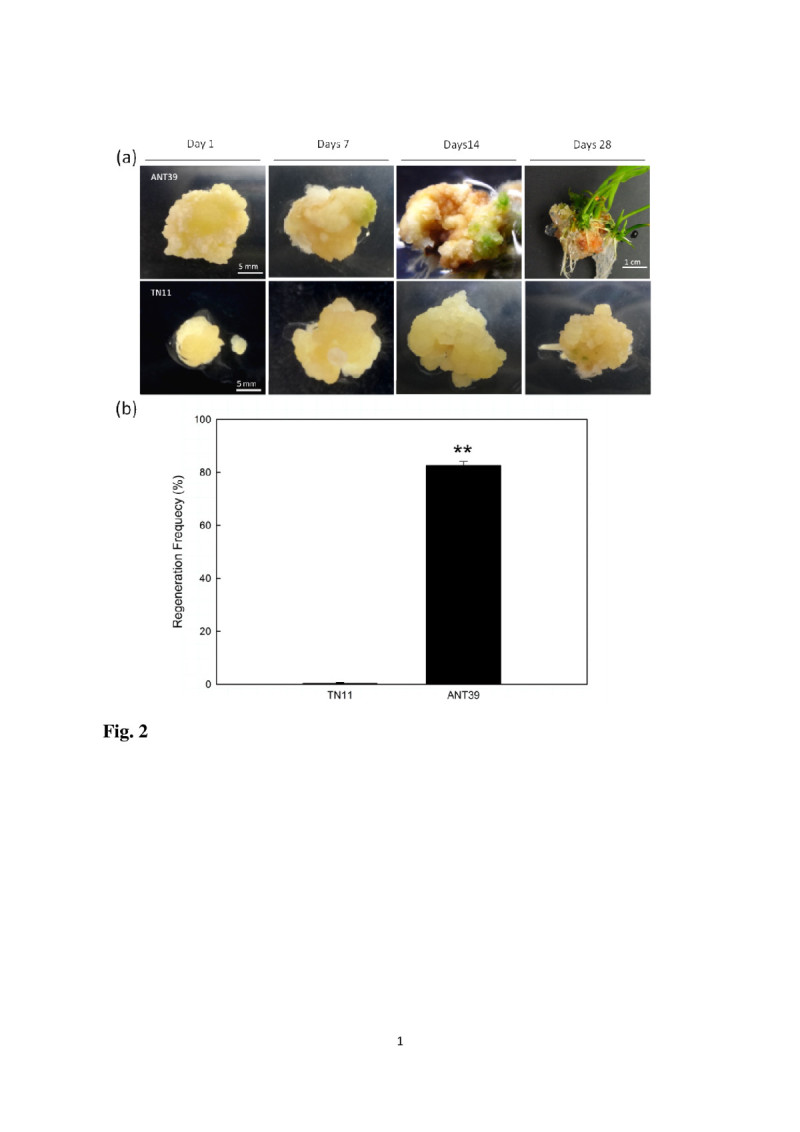

After transfer to RM, the green spots observed at day 7 in ANT39 calli and continuously spread out, especially at the side contact with the media. The multiple shoots could be emerged after 3 weeks in RM and whole plantlets are further growth (Figure 2a). The shoot organogenic frequency of ANT39 is approximately to 80% (Figure 2b). In contrast, TN11 calli are continue to growth and have no shoot regenerated in RM. Several calli of TN11 only emerged green spots and adventitious roots at late regeneration stage (Figure 2a). In this study, ANT39 and TN11 belong to the highly regenerable (HR) and non-regenerable (NR) cultivar, respectively. ANT39 is the only one cultivar we surveyed in rice possess high shoot regeneration ability without extra osmotic stress treatment during callus induction (Huang et al., 2002). It is suitable used to clarify the possible mechanism with respect to shoot regeneration in rice.

Figure 2.

Shoot organogenesis of 14-day-old callus transferred to regeneration media for 4 weeks. (a) Morphology of ANT39 and TN11 callus during shoot organogenesis. (b) Shoot regeneration frequency. Plantlets higher than 1 cm were recorded. Data are mean ± standard error (n=3). ** denotes significant difference between ANT39 and TN11 based on the level of 0.01.

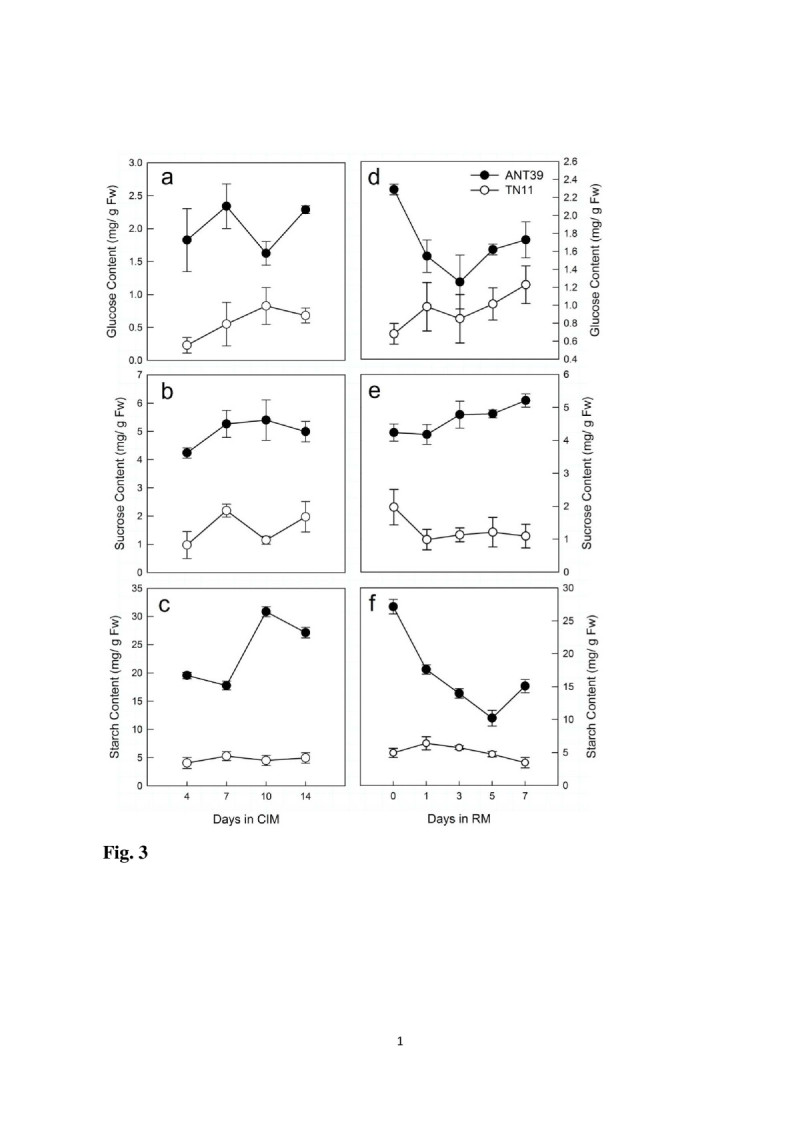

Relation of carbohydrates content and shoot organogenesis ability

To clarify the relationship between shoot organogenesis ability and carbohydrate metabolism, glucose, sucrose and starch contents were determined at callus induction and early shoot regeneration stage. The result showed that glucose, sucrose, and starch contents are all significant higher in the HR calli, ANT39, than in NR calli, TN11, either at callus induction or regeneration period (Figure 3). The high carbohydrate content in ANT39 was maintained during callus induction (Figure 3a-c), but the levels of glucose and starch are gradually decreased after transferred to RM in 7 days (Figure 3d, f). All glucose, sucrose, and starch contents in TN11 calli are low and have no significant change during the whole evaluation time. The carbohydrate utilization is higher in ANT39 than in TN11 calli would supply to the energy and osmotic requirement of callus formation and starch accumulation. ANT39 callus possesses high level of starch mainly caused from higher biosynthetic activity and is also observed in our previous study by histochemical analysis (Huang et al., 2006). Besides, high levels of cellular carbohydrates associated with shoot organogenesis in rice callus are similar to the regeneration system induced by osmotic stress (Huang and Liu, 2002).

Figure 3.

Carbohydrate content during callus induction and early shoot organogenesis in rice. Glucose, sucrose and starch content in ANT39 and TN11 calli inoculated in callus induction media (CIM; a-c) and regeneration media (RM; d-f). Data are mean ± standard error (n=3).

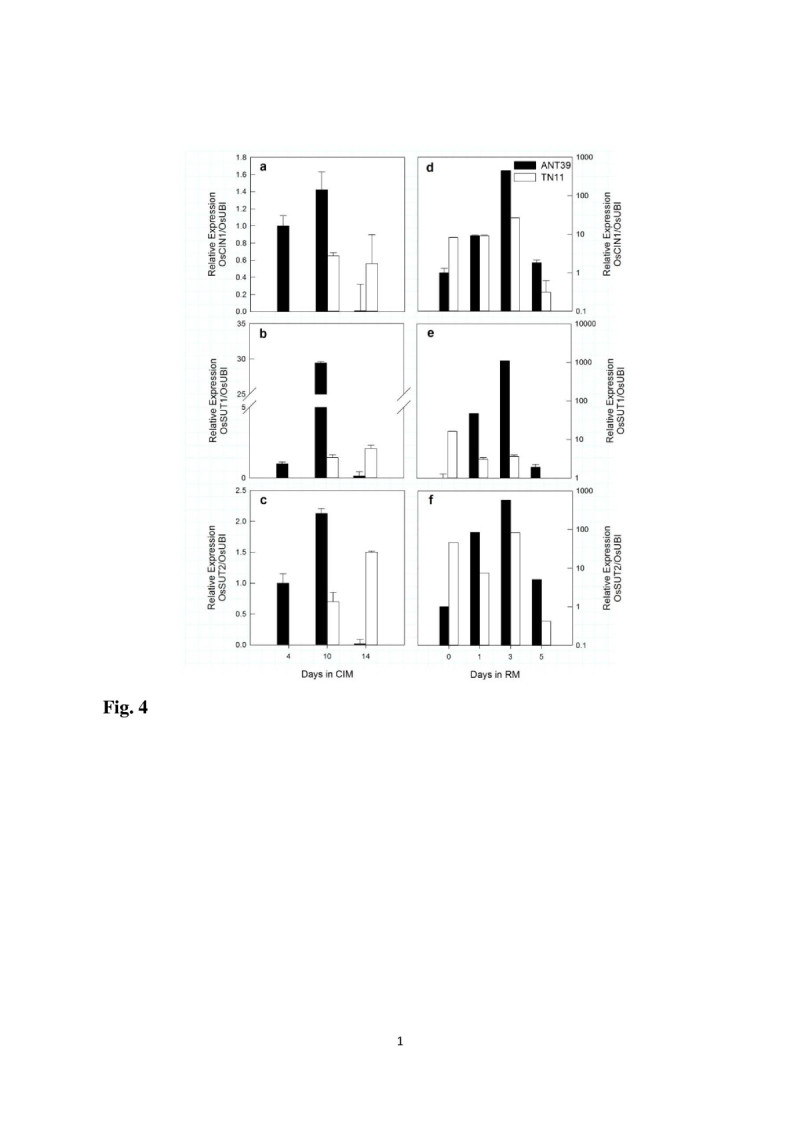

Expression of sucrose metabolic enzymes in rice calli

According to changes in carbohydrate contents, the efficiency of sucrose uptake and hydrolysis from media is related to calli growth and cell differentiation. We thus determined the mRNA expression of OsCIN1 and OsSUTs during callus induction and early shoot regeneration. OsCIN1 expression was high in ANT39 from days 4 to days 10 with CIM inoculation then greatly decreased (Figure 4a). The higher expression patterns of OsSUT1 and OsSUT2 were similar to OsCIN1 in ANT39 during callus induction (Figure 4b, 4c). Conversely, these genes did not detected in TN11 calli until days 10 inoculated on CIM; their expression remained high continue to days 14 (Figure 4a-c). These results are identical to the determination of sucrose and glucose contents.

Figure 4.

Real time-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of OsCIN1 , OsSUT1 and OsSUT2 in rice immature seeds during callus induction and early shoot organogenesis. (a-c) OsCIN1, OsSUT1 and OsSUT2 levels at days 4, 10 and 14 in CIM. The levels were normalized to that at day 4 in ANT39. (d-f) OsCIN1, OsSUT1 and OsSUT2 levels at days 0, 1, 3 and 5 in RM. Levels were normalized to that at day 0 of ANT39 in RM. Ubiquitin level was used as a reference. Data are mean ± standard error (n=3).

In ANT39 calli, after being transferred to RM, OsCIN1 expression was significantly induced at the first day and greatly increased at the day 3 (almost 1000-folds). After that, the expression gradually decreased. Like the expression of OsCIN1, that of OsSUT1 and OsSUT2 was up-regulated at the days 1 and days 3 in RM, then decreased quickly at the days 5 (Figure 4d-f). In contrast, in NR calli, TN11, the expressions of OsCIN1 and OsSUT2 were steady in RM, and reduced expression of OsSUT1 at the days 1. Thus, regardless of callus induction or shoot regeneration stage, ANT39 showed high efficient sucrose uptake and utilization, which would explain the faster callus formation and shoot organogenesis in ANT39 than in TN11.

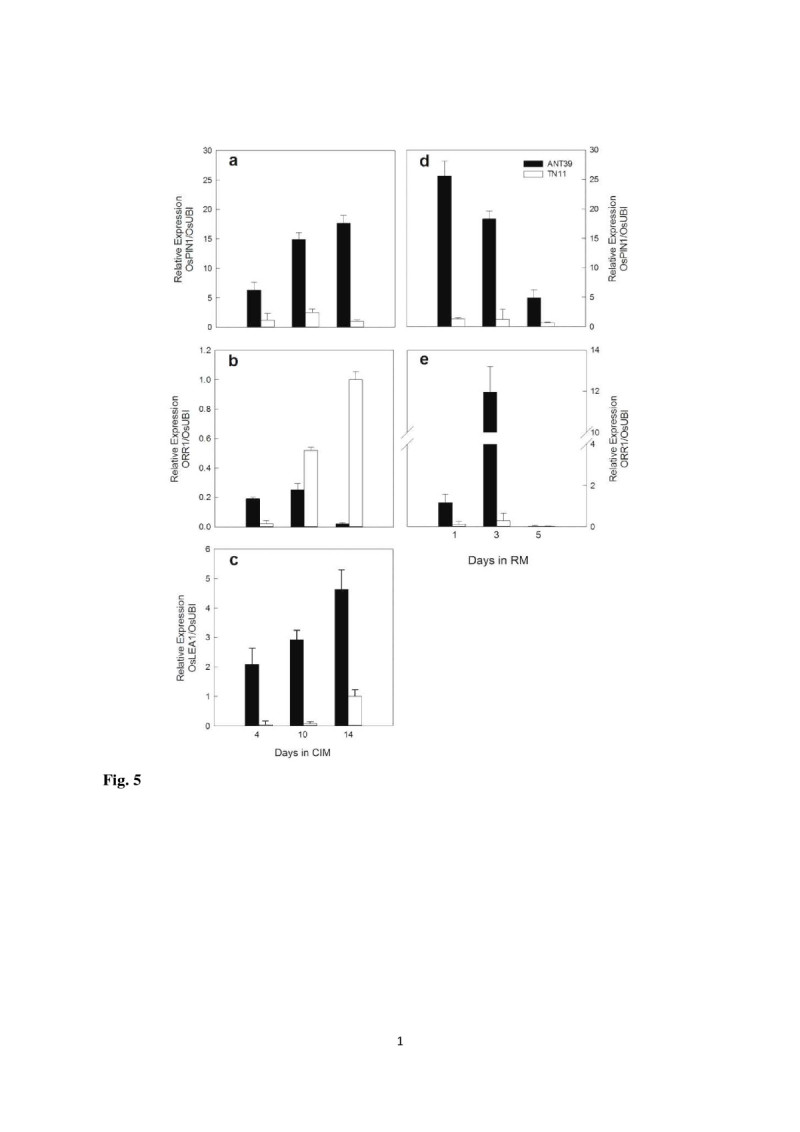

Cytokinin, auxin, and ABA signals are related to sucrose uptake

High levels of endogenous auxin, ABA, and zeatin in high regenerable calli are observed in our previous study (Liu and Lee, 1996; Huang et al., 2012). To clarify the relationship between plant hormones and carbohydrate metabolism in rice calli, we determined the expression patterns of the B-type response regulator of cytokinin signaling ORR1 and auxin efflux carrier OsPIN1 (Xu et al., 2006), and late embryogenesis-abundant gene OsLEA1. OsPIN1 was highly expressed in ANT39 both at callus induction and shoot organogenesis stages but was low in TN11 and did not change during the whole evaluation period (Figure 5a, 5d). The high expression level of OsLEA1 is also detected at CIM in ANT39 (Figure 5c). CIM was not supplemented with exogenous cytokinin; thus, the expression level of ORR1 was the mean endogenous cytokinin level. ORR1 showed high expression at the early stage in ANT39 calli but higher expression in TN11 at the tenth-day (Figure 5b). After transferred to RM, the expression of ORR1 was strongly induced in ANT39 on days 1 and 3 because of exogenous kinetin included in the RM. However, the expression of ORR1 in TN11 did not significant difference during the same regeneration period (Figure 5e). Besides, the expression of OsLEA1 both in ANT39 and TN11 at early shoot regeneration stage are very low and have no different significantly (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Real time-PCR quantification of mRNA levels of OsPIN1 , ORR1 and OsLEA1 in rice immature seeds during callus induction (CIM) and early shoot organogenesis (RM). (a, d) OsPIN1 levels. (b, e) ORR1 levels. (c) OsLEA1 level. Levels were normalized to that at day 14 of TN11 in CIM. Ubiquitin level was used as a reference. Data are mean ± standard error (n=3).

Discussion

Although shoot regeneration and transformation systems are well developed in rice callus, the regeneration frequency is commonly low and is cultivars-dependent (Huang et al., 2002; Khaleda and Al-Forkan 2006; Dabul et al., 2009). Shoot regeneration ability can be greatly enhanced by high osmotic stress treatment during callus induction (Huang and Liu, 2002; Huang et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2012). As well, stress-treated calli have lower water content, water potential, and fresh weight but higher glucose and starch contents (Huang and Liu, 2002). ANT39 is a unique cultivar which has high shoot organogenic ability without extra-osmotic stress treatment (Huang et al., 2002). At present study, calli fresh weight was higher but water content lower in ANT39 calli than in non-regenerable TN11 calli (Figure 1b, 1c). No matter of ANT39 or osmotic-induced regeneration system in rice, to initiate the embryogenic calli or organogenic meristemoids at the callus induction stage is the most critical point for further plantlets regeneration (Sugiyama, 1999; Huang and Liu, 2002; Huang et al., 2012).

Carbon sources, phytohormones, and genotypes are well known to affect shoot regeneration in cultured cells. However, the cross-talk among these factors is still little understood. Sucrose is the main carbohydrate supplemented into the culture media and prominently acts as an energy source and osmotic requirement during organogenesis (Verma and Dougall, 1977; Thorpe et al., 1986; Iraqi et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2010; Silva, 2010). The correlation between starch metabolism and shoot regeneration was also reported in tobacco (Thorpe et al., 1986), sugarcane (Ho and Vasil, 1983), Begonia (Mangat et al., 1990) and rice (Huang et al., 2006). However, little is known about the signals to trigger sucrose metabolism in cultured cells, especially at the gene expression level. Here, we found that the possible route from plant hormone auxin, cytokinin and ABA to shoot organogenesis may be through sucrose metabolism in rice callus. Exogenous plant hormones or plant growth regulators used to induce shoot organogenesis interact with endogenous tissue-specific hormones; thus, the level of endogenous hormones in cultured explants and derived calli may be the most important factor in shoot organogenesis. In our previous studies, highly regenerable calli showed high level of endogenous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and ABA during whole callus induction; however, high levels of zeatin/zeatin ribosides only showed at 1 week then gradually decreased in CIM. The levels of IAA and ABA quickly decreased and that of zeatin/zeatin ribosides predominantly increased after being transferred to shoot regeneration media (Liu and Lee, 1996; Huang et al., 2012).

ANT39 calli showed high levels of sucrose, glucose and starch (Figure 3). Moreover, the mRNA expression of both OsCIN1 and OsSUT2 was significantly induced at the early callus induction stage in ANT39 but it can be detected only at the late stage in TN11 (Figure 4). The high level of cellular sucrose in ANT39 calli may due to direct uptake from media by the sucrose transporter (Figure 4b, 4c). As well, the high glucose content was hydrolyzed by cell wall-bound invertase from sucrose in the culture media (Figure 4a) and from cellular sucrose hydrolysis by soluble invertase and sucrose synthase (Huang et al., unpublished data). However, only a high level of glucose was identified in osmotic stress-treated rice calli, with no difference in sucrose content (Huang and Liu, 2002). The high starch content in ANT39 during callus induction resulted from higher starch biosynthetic enzyme activity but may due to lower degradation activity in osmotic-treated calli (Huang and Liu, 2002; Huang et al., 2006). After transfer to RM, non-regenerable TN11 calli always maintained lower sucrose, glucose and starch contents than that from ANT39 during the evaluated period (Figure 3). However, the content of these carbohydrates were significant higher in ANT39 than in TN11 calli. The higher glucose and sucrose contents may result from uptake through the sucrose transporter and further hydrolysis in ANT39 (Figure 4) but may be hydrolyzed by CIN before sucrose uptake in the osmotic-induced regeneration system (Huang and Liu, 2002). Thus, the signals and carbohydrate metabolism pathway affecting shoot organogenesis in ANT39 calli may differ with osmotic-stress induced regeneration system in rice.

Both exogenous and endogenous plant hormones trigger callus formation and further cell differentiation in plant tissue culture (Barreto et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2010; Sun and Hong, 2010; Huang et al., 2012). Exogenous plant hormones or plant growth regulators used to induce shoot organogenesis interact with endogenous tissue-specific hormones; thus, the level of endogenous hormones in cultured explants and derived calli may be the most important factor in shoot organogenesis (Huang et al., 2012). How the endogenous hormones signals, especially those of cytokinin, ABA, and auxin, affect cell growth and differentiations are less understood. We determined the expression patterns of ORR1 as related endogenous cytokinin level (Mason et al., 2005), OsPIN1 as related endogenous auxin level (Sauer et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2012) and OsLEA1 as related endogenous ABA level (Grelet et al., 2005; Shih et al., 2010), respectively. In ANT39 calli, all ORR1, OsPIN1 and OsLEA1 were strongly induced at the early stage in CIM, but ORR1 was greatly reduced after days 10 in CIM (Figure 5). In contrast, in TN11 calli, they showed low expressions, except that ORR1 expression increased after days 10 in CIM. All the expression of phytohormones responsive genes are consistence with endogenous levels of IAA, ABA, and zeatins determined from our previous study (Liu and Lee 1996; Huang et al., 2012). The high levels of endogenous IAA and cytokinin at early callus induction stage in highly regenerable cultivar may response to initiate callus formation and amplification (Skoog et al., 1965). Besides, high level of ABA at late stage in CIM is related to induce organogenic callus formation (Brown et al., 1989; Huang et al., 2012). In addition, the expression patterns of ORR1 and OsPIN1 agree with those of OsCIN1 and OsSUTs. Cytokinins and auxins affecting CIN and SUTs have been found in whole plant systems (Ehness and Roitsch, 1997; Hartig and Beck, 2006; Walters and McRoberts, 2006). Our data showed that both hormones have a similar effect on carbohydrate metabolism during callus induction and shoot organogenesis. In ANT39 regenerable callus, endogenous cytokinin triggered OsCIN1 and OsSUTs gene expression and gained sucrose absorption ability during early callus induction. The expression of OsCIN1 and OsSUTs are strongly inhibited when the auxin transport inhibitor, 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid, was supplemented into the CIM (Huang et al., unpublished data ). These expression patterns of sucrose metabolism related genes are positive correlated to the expression pattern of OsPIN1 gene in CIM but is negative correlated in RM. The reason is high level of IAA response to initiate organogenic or embryogenic competence cell in CIM, however it would be related to root formation at late stage in RM. Besides, the ratio of auxin/cytokinin is higher in CIM may affect the expression of OsCIN1 and OsSUTs. The sucrose absorbed or hydrolyzed in ANT39 callus provided starch biosynthesis as well as energy requirements for cell growth. Our previous histochemical analysis revealed abundant starch granules around whole calli in ANT39 but not non-regenerable rice calli (Huang et al., 2006).

Conclusions

Finally, we found that plant hormones signaling and carbohydrate metabolism are closely related to shoot organogenesis in rice callus. The explants of the highly regenerable cultivar ANT39 may more sensitive to CIM (MS basal medium containing 3% sucrose and 10 μM 2, 4-D) to quickly increase the levels of endogenous ABA, cytokinin and auxin. The high levels of phytohormones immediately trigger sucrose uptake from the media by a sucrose transporter or cell wall-bound invertase. The high amounts of glucose and sucrose contents provide for callus induction and growth and increase starch biosynthesis. After transferred to RM (MS medium with 3% sucrose, 20 μM kinetin and 10 μM NAA), exogenous kinetin and NAA led to sucrose absorption and hydrolysis to provide the energy to initiate shoot organogenesis and further development. We reveal the association among phytohormones, sucrose metabolism, and shoot organogenesis in rice calli. However, the signal transduction pathways of plant hormones to sucrose and starch metabolism still need to be further determined.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Council of Agriculture, Taiwan.

Abbreviations

- 2

4-D: 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- CIM

Callus induction medium

- CIN

Cell wall-bound invertase

- NAA

1-naphthalene acetic acid

- ORR1

ORYZA SATIVA RESPONSE REGULATOR 1

- PGRs

Plant growth regulators

- PIN

PIN-formed protein

- RM

Regeneration medium

- SUT

Sucrose transporter.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1999-3110-54-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

S-TL responsible for rice cultivation, tissue culture, sampling, biochemical and molecular analysis and data analysis presented in this paper. W-LH designed the experiment, supply all the instruments analyzed in this study, and also drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Shiang-Ting Lee, Email: s1000024@mail.ncyu.edu.tw.

Wen-Lii Huang, Email: wlhuang@mail.ncyu.edu.tw.

References

- Amino S, Tazawa M. Uptake and utilization of sugars in cultured rice cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 1988;183:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto R, Nieto-Sotelo J, Cassab GI. Influence of plant growth regulators and water stress on ramet induction, rosette engrossment and fructan accumulation in Agave tequilana Weber var. Azul. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;103:93–101. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9758-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Brooks FJ, Pearson D, Mathias RJ. Control of embryogenesis and organogenesis in immature wheat embryo callus using increased medium osmolarity and abscisic acid. J Plant Physiol. 1989;133:727–733. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(89)80080-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Liu SL, Wei S, Wang SJ. Hormone and sugar effects on rice sucrose transporter OsSUT1 expression in germinating embryos. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32:749–756. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0459-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Zhu S, Gao X, Zhang X. Cytokinin and auxin regulates WUS induction and inflorescence regeneration in vitro in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29:927–960. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0879-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Lee SK, Ko S, Kim HK, Jun SH, Lee YH, Bhoo SH, Lee KW, An G, Hahn TR, Jeon JS. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of the cell-wall invertase gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Cell Rep. 2005;24:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0910-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado Y, Guerra H, Belen A. Differences in invertase activity in embryogenic and non-embryogenic calli from Medicago arborea. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2001;67:145–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1011917013886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dabul ANG, Belefant-Miller H, RoyChowdhury M, Hubstenberger JF, Lorence A, Phillips GC. Screening of a board range of rice (Oryza sativa L.) germplasm for in vitro rapid plant regeneration and development of an early prediction system. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Plant. 2009;45:414–420. doi: 10.1007/s11627-008-9174-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehness R, Roitsch T. Co-ordinated induction of mRNAs for extracellular invertase and a glucose transporter in Chenopodium rubrum by cytokinins. Plant J. 1997;11:539–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11030539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JC, Yu XM, Shang XL, Li JD, Wu YX. Factors influencing efficiency of shoot regeneration in Ziziphus jujuba Mill. ‘Huizao’. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;101:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s11240-009-9663-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacha K, Jezowski S, Kaczmarek Z. The effects of genotype, inflorescence developmental stage and induction medium on callus induction and plant regeneration in two Miscanthus species. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;102:79–86. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9708-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grelet J, Benamar A, Teyssier E, Avelange-Macherel MH, Grunwald D, Macherel D. Identification in pea seed mitochondria of a late-embryogenesis abundant protein able to protect enzymes from drying. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:157–167. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Paul MJ. Carbon metabolism sensing and signaling. Plant Biotechnol J. 2003;1:381–398. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-7652.2003.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig K, Beck E. Crosstalk between auxin, cytokinin and sugars in the plant cell cycle. Plant Biol. 2006;8:389–396. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-923797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Makoto T, Tomio T. Cell wall invertase in developing rice caryopsis: molecular cloning of OsCIN1 and analysis of its expression in relation to its role in grain filling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:452–459. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WJ, Vasil IK. Somatic embryogenesis in sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.): growth and plant regeneration from embryogenic cell suspension cultures. Ann Bot. 1983;51:719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque M, Mansfied J. Effect of genotype and explants age on callus induction and subsequent plant regeneration from root-derived callus of indica rice genotypes. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2004;78:217–223. doi: 10.1023/B:TICU.0000025640.75168.2d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Zago MK, Abas L, van Marion A, Ampudia CSG, Offringa R. Phosphorylation of conserved PIN motifs directs Arabidopsis PIN1 polarity and auxin transport. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1129–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WL, Lee CH, Chen YR. Levels of endogenous abscisic acid and indole-3-acetic acid influence shoot organogenesis in callus cultures of rice subjected to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2012;108:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-0038-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WL, Liu LF. Carbohydrate metabolism in rice during callus induction and shoot regeneration induced by osmotic stress. Bot Bull Acad Sin. 2002;43:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Huang WL, Tsung YC, Liu LF. Osmotic stress promotes shoot regeneration in immature embryo-derived callus of rice (Oryza sativa L.) J Agric Assoc China. 2002;3:76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Huang WL, Wang YC, Lee PD, Liu LF. The regenerability of rice callus is closely related to starch metabolism. Taiwanese J Agric Chem Food Sci. 2006;44:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Iraqi D, Le V, Lamhamedi M, Tremblay F. Sucrose utilization during somatic embryo development in black spruce: involvement of apoplastic invertase in the tissue and of extracellular invertase in the medium. J Plant Physiol. 2005;162:115–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Kurata N. Identification and characterization of cytokinin-signalling gene families in rice. Gene. 2006;382:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Van den Ende W, Laere A, Cheng S, Bennett J. Structure, evolution, and expression of the two invertase gene families of rice. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:615–634. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Chen J, Gao XL, Wan J, Wang PR, Wang XD, Xu ZJ. Effect of ABA on rice callus and development of somatic embryo and plant regeneration. Acta Agron Sin. 2006;32:1379–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez VM. Involvement of plant hormone and plant growth regulators on in vitro somatic embryogenesis. Plant Growth Regul. 2005;47:91–110. doi: 10.1007/s10725-005-3478-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavi Kishor PB, Rao JD, Reddy G. Activity of wall-bound enzymes in callus cultures of Gossypium hirsutum L. during growth. Ann Bot. 1992;69:145–294. [Google Scholar]

- Khaleda L, Al-Forkan M. Genotypic variability in callus induction and plant regeneration through somatic embryogenesis of five deepwater rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars of Bangladesh. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:1435–1440. [Google Scholar]

- León P, Sheen J. Sugar and hormone connections. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:110–116. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LF, Lee CH. Changes of endogenous phytohormones during plant regeneration from rice callus. In: Khush GS, editor. Rice Genetics III. Proceedings of the Third International Rice Genetics Symposium. Manila, Philippines: International Rice Research Institutive; 1996. pp. 525–531. [Google Scholar]

- Mangat BS, Pelekis MK, Cassells AK. Changes in the starch content during organogenesis in in vitro cultured Begonia rex stem explants. Physiol Plant. 1990;79:267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1990.tb06741.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Mathews D, Argyros D, Maxwell B, Kieber J, Alonso J, Ecker J, Schaller G. Multiple type-B response regulators mediate cytokinin signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3007–3025. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller B, Sheen J. Advence in cytokinin signaling. Science. 2007;318:68–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1145461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A reviesd medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZY, Zhu SP, Guan R, Deng XX. Identification of 2,4-D responsive proteins in embryogenic callus of Valencia sweet orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) following osmotic stress. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;103:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9762-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Cho HM, Moon HK, Kim YW, Paek KY. Genotypic variation and aging effects on the embryogenic capacity of Kalopanax septemlobus. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2011;105:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9862-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pernisová M, Klíma P, Horák J, Válková M, Malbeck J, Soucek P, Reichman P, Hoyerová K, Dubová J, Friml J. Cytokinins modulate auxin- induced organogenesis in plants via regulation of the auxin efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3609–3623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811539106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrásek J, Mravec J, Bouchard R, Blakeslee JJ, Abas M, Seifertová D, Wisniewska J, Tadele Z, Kubes M, Covanová M, Dhonukshe P, Skupa P, Benková E, Perry L, Krecek P, Lee OR, Fink GR, Geisler M, Murphy AS, Luschnig C, Zazímalová E, Friml J. PIN proteins perform a rate-limiting function in cellular auxin effux. Science. 2006;312:914–918. doi: 10.1126/science.1123542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert J. The control of morphogenesis and induction of adventitious embryos in cell cultures of carrots. Planta. 1959;53:318–333. doi: 10.1007/BF01881795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roitsch T, Balibrea ME, Hofmann M, Proels R, Sinha AK. Extracellular invertase: key metabolic enzyme and PR protein. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:513–524. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer M, Balla J, Luschnig C, Wisniewska J, Reinöhl V, Friml J, Benková E. Canalization of auxin flow by Aux/IAA-ARF-dependent feedback regulation of PIN polarity. Gene Dev. 2006;20:2902–2913. doi: 10.1101/gad.390806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz U, Lorz H. Nutrient uptake in suspension cultures of gramineae. II. Suspension cultures of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Sci. 1990;66:95–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(90)90174-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scofield G, Hirose T, Aoki N, Furbank R. Involvement of the sucrose transporter, OsSUT1, in the long-distance pathway for assimilate transport in rice. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:3155–3224. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih MD, Huang LT, Wei FJ, Wu MT, Hoekstra FA, Hsing YI. OsLEA1a, a new Em-like protein of cereal plants. Plant Cell Physiology. 2010;51:2132–2144. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahpoosh M, Sanchez D, Schlereth A, Scofield G, Furbank R, van Dongen J, Kopka J. Modification of OsSUT1 gene expression modulates the salt response of rice Oryza sativa cv. Taipei 309. Plant Sci. 2012;182:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siao W, Chen JY, Hsiao HH, Chung P, Wang SJ. Characterization of OsSUT2 expression and regulation in germinating embryos of rice seeds. Rice. 2011;4:39–49. doi: 10.1007/s12284-011-9063-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva TD. Indica rice anther culture: can the impasse be surpassed? Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;100:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11240-009-9616-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog F, Strong F, Miller C. Cytokinins. Science. 1965;48:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.148.3669.532-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Zhao X, Liu Y, Zhang C, O'Neill S, Zhang X. Auxin-induced WUS expression is essential for embryonic stem cell renewal during somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;59:448–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama M. Organogenesis in vitro. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1999;2:61–64. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(99)80012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YL, Hong SK. Effects of plant growth regulators and L-glutamic acid on shoot organogenesis in the halophyte Leymus chinensis (Trin.) Organ Cult Plant Cell Tiss. 2010;100:317–328. doi: 10.1007/s11240-009-9653-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Lüscher M, Sturm A. Antisense repression of vacuolar and cell wall invertase in transgenic carrot alters early plant development and sucrose partitioning. Plant Cell. 1999;11:177–266. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe TA, Joy RW, Leung DWM. Starch turnover in shoot-forming tobacco callus. Physiol Plant. 1986;66:58–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1986.tb01233.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YC, Weir NR, Hill K, Zhang W, Kim HJ, Shiu SH, Schaller GE, Kieber JJ. Characterization of genes involved in cytokinin signalling and metabolism from rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1666–1684. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste S, Friml J. Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell. 2009;136:1005–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma DC, Dougall DK. Influence of carbohydrates on quantitative aspects of growth and embryo formation in wild carrot suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:81–85. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters DR, McRoberts N. Plants and biotrophs: a pivotal role for cytokinins? Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Xu X, Zhang L, Zhang H, Lin L, Wang Q, Li Q, Ge S, Lu BR, Wang W, He Z. Duplication and independent selection of cell-wall invertase genes GIF1 and OsCIN1 during rice evolution and domestication. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:108–110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JR, Hu H, Wang GH, Li J, Chen JY, Wu P. Expression of PIN genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.): tissue specificity and regulation by hormones. Mol Plant. 2009;2:823–831. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YQ, Wei XL, Xu HL, Chai CL, Meng K, Zhai HL, Sun AJ, Peng YG, Wu B, Xiao GF, Zhu Z. Cell-wall invertase form rice are differentially expressed in caryopsis during the grain filling stage. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:466–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani SH, Sanghera GS, Gosal SS. An efficient and reproducible method for regeneration of whole plants from mature seeds of a high yielding indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) variety PAU 201. N Biotechnol. 2011;28:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Hofhuis H, Heidstra R, Sauer M, Friml J, Scheres B. A molecular framework for plant regeneration. Science. 2006;311:385–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1121790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Lan Y, Zhu L. Analysis of the protein expression profiling during rice callus differentiation under different plant hormone conditions. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;68:597–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi MA, Narayanan M, Sardana R, Taga I, Postel S, Johns R, McNulty M, Mottiar Y, Mao J, Loit E, Altosaar I. Optimizing tissue culture media for efficient transformation of different indica rice genotypes. Agron Res. 2006;4:563–575. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhou J, Wu T, Cao J. Shoot regeneration and the relationship between organogenic capacity and endogenous hormonal contents in pumpkin. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2008;93:323–654. doi: 10.1007/s11240-008-9380-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Andersen S, Ljung K, Dolezal K, Miotk A, Schultheiss S, Lohmann J. Hormonal control of the shoot stem-cell niche. Nature. 2010;465:1089–1181. doi: 10.1038/nature09126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]