Abstract

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in adolescents and young adults with bleeding disorders is under-researched. We aimed to describe factors related to HRQoL in adolescents and young adults with hemophilia A or B or von Willebrand disease.

Methods

A convenience sample of volunteers aged 13 to 25 years with hemophilia or von Willebrand disease completed a cross-sectional survey that assessed Physical (PCS) and Mental (MCS) Component Summary scores on the SF-36 questionnaire. Quantile regression models were used to assess factors associated with HRQoL.

Results

Of 108 respondents, 79, 7, and 14% had hemophilia A, hemophilia B, and von Willebrand disease, respectively. Most had severe disease (71%), had never developed an inhibitor (65%), and were treated prophylactically (68%). Half of patients were aged 13 to 17 years and most were white (80%) and non-Hispanic (89%). Chronic pain was reported as moderate to severe by 31% of respondents. Median PCS and MCS were 81.3 and 75.5, respectively. Quantile regression showed that the median PCS for women (61% with von Willebrand disease) was 13.1 (95% CI: 2.4, 23.8; p = 0.02) points lower than men. Ever developing an inhibitor (vs never) was associated with a 13.1-point (95% CI: 4.7, 21.5; p < 0.01) PCS reduction. MCS was 10.0 points (95% CI: 0.7, 19.3; p = 0.04) higher for prophylactic infusers versus those using on-demand treatment. Compared with patients with no to mild chronic pain, those with moderate to severe chronic pain had 25.5-point (95% CI: 17.2, 33.8; p < 0.001) and 10.0-point (95% CI: 0.8, 19.2; p = 0.03) reductions in median PCS and MCS, respectively.

Conclusions

Efforts should be made to prevent and manage chronic pain, which was strongly related to physical and mental HRQoL, in adolescents and young adults with hemophilia and von Willebrand disease. Previous research suggests that better clotting factor adherence may be associated with less chronic pain.

Keywords: Chronic pain, Hemophilia, Pain management, Patient adherence, Prophylaxis, von Willebrand disease

Background

Therapeutic advancements [1–4], improved treatment approaches [5–8], and enhanced care delivery models [9–12] have resulted in highly active lifestyles and near-normal life expectancy for persons diagnosed with a bleeding disorder [13]. As treatments continue to improve, patient care will continue to evolve toward preventing bleeding disorder complications, such as hemophilic arthropathy, chronic pain, and inhibitor development—with the ultimate goal of attaining and maintaining high health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for those affected by the disorder [14]. Previous research has shown that among persons with a bleeding disorder, HRQoL may be related to pain, treatment type (prophylaxis vs on-demand), adherence, age-related concerns, inhibitor status, or depression [14–21]. These findings suggest that bleeding disorders particularly diminish the physical aspects of HRQoL and that alleviating the clinical burden of bleeding disorders may be particularly important for improving and maintaining physical well-being and overall HRQoL.

Measuring HRQoL is a unique way to assess the general well-being and perceived health of individuals living with a bleeding disorder, the experiences related to having a bleeding disorder, and satisfaction with treatment [22]. However, very little, if any, data exist that describe HRQoL among adolescent and young adult (AYA) persons diagnosed with a bleeding disorder. AYAs are a unique population of bleeding disorder patients who are often just starting to take more responsibility for the management of their own disease and developing treatment habits that can carry over into adult life [23]. Entering adolescence and young adulthood might mean finally confronting the demands that managing a bleeding disorder entails. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between pain management, adherence to prescribed treatment, and HRQoL in AYA persons with hemophilia (PWH) or von Willebrand disease (VWD).

Methods

Study population and recruitment

Data describing HRQoL, adherence to prescribed treatment regimens, and level of chronic pain among AYA PWH or VWD were obtained as part of the larger Interrelationship Between Management of Pain, Adherence to Clotting-factor Treatment, and Quality of Life (IMPACT QoL) study. As the name suggests, the IMPACT QoL study had the primary goal of assessing the relationship between validated measures of pain, clotting-factor adherence, and HRQoL among AYA PWH or VWD. Data describing the relationship between adherence to a prescribed clotting factor treatment regimen and chronic pain, along with racial differences in chronic pain and QoL from this study, were previously reported [24, 25]. Data were collected via a one-time, cross-sectional, online survey from a convenience sample of AYA PWH or VWD. To be eligible to complete the survey, participants had to be aged 13 to 25 years, read, write, and speak English, and have hemophilia A, hemophilia B, or VWD. Recruitment occurred at major US hemophilia meetings (e.g., Inhibitor Summits and National Hemophilia Foundation meetings), US hemophilia treatment centers, and through a Facebook© page dedicated to the study from April through December of 2012. All surveys were completed electronically using SurveyMonkey® and Apple® iPads®. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the Munson Medical Center (Traverse City, MI) institutional review board prior to data collection. All data were de-identified prior to analysis. The current study uses the IMPACT QoL survey data to determine factors associated with better HRQoL among AYA (aged 13–25 years) PWH or VWD.

Measurement

HRQoL was measured using the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 is composed of 8 multi-item scales (35 items) assessing the following: (1) bodily pain (BP, 2 items), (2) physical function (PF, 10 items), (3) role limitations due to physical health problems (RP, 4 items), (4) general health (GH, 5 items), (5) vitality (VT, 4 items), (6) social functioning (SF, 2 items), and (7) role limitations due to emotional problems (RE, 3 items) and emotional well-being/mental health (MH, 5 items) [26]. The 36th item, which asks about health change, is not included in the scale or summary scores. Each subscale is calculated by taking the average of the participant’s responses to the questions contained in the subscale and then standardizing it so that each had a final range of 0 (lowest level of functioning) to 100 (highest level of functioning). These eight scales can be aggregated into two summary measures: the Physical (PCS) and Mental (MCS) Component Summary scores, where higher scores represent better health. The scoring algorithm for PCS includes positive weights for the PF, RP, BP, GH, and VT scales and negative weights for the SF, RE, and MH. The scoring algorithm for MCS includes positive weights for the VT, SF, RE, and MH scales and negative weights for the PF, RP, BP, and GH scales. Three scales (PF, RP, and BP) correlate most highly with the physical component and contribute most to the scoring of the PCS. The MCS correlates most highly with the MH, RE, and SF scales, which also contribute most to the scoring of the MCS measure. Three of the scales (VT, GH, and SF) have noteworthy correlations with both components. The SF-36 was constructed for self-administration by persons 14 years of age and older, and for administration by a trained interviewer in person or by telephone [26].

Adherence was assessed using the Validated Hemophilia Regimen Treatment Adherence Scale (VERITAS)-Pro [27] and VERITAS-PRN [28] for prophylactic and on-demand (i.e., episodic) participants, respectively. VERITAS scores range from 24 (most adherent) to 120 (least adherent). As an experimental measure, we also combined VERITAS-Pro and VERITAS-PRN responses into one category (VERITAS-combined) [25] to evaluate the relationship between adherence and HRQoL for both prophylactic and on-demand AYA PWH simultaneously. The cutoff for non-adherent prophylactic participants was a total VERITAS-Pro score ≥57 as previously established [27]. The cutoff for non-adherent on-demand patients has not been previously described and was defined as those with VERITAS-PRN in the highest quartile of all responses. This value was chosen because the VERITAS-Pro cutoff was approximately the 75th percentile of all responses.

Chronic pain was measured using the revised Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R). The FPS-R is a visual scale composed of six faces illustrating an increasing level of pain intensity. Respondents were asked to choose the face that best describes the intensity of the chronic pain they experienced. In the IMPACT HRQoL survey, chronic pain was defined as ‘pain that you have every day or almost every day, and that always or almost always seems to be there even when you are not having a bleed at that moment.’ FPS-R scores range from 0 to 10 with the faces representing the lowest and highest levels of pain intensity coded as 0 and 10, respectively. The FPS-R is highly correlated with the visual analog scale (r = .93) and with the colored analog scale (r = .84), demonstrating strong validity. Reliability and validity of the FPS-R have been established for a broad age range, ranging from children as young as 4 years old to adults [29]. For purpose of analysis, chronic pain was dichotomized as high for those who reported their pain as ‘moderate,’ ‘severe,’ ‘very severe,’ or ‘worst pain possible’ (i.e., FPS-R ≥4) and low for ‘mild pain’ or ‘no pain’ (i.e., FPS-R <4).

Other self-reported data collected included information about participant age, gender, race, ethnicity, health insurance status/type, and the educational level of the participants’ parents. Data were also collected about bleeding disorder type (hemophilia A or B, or VWD), whether or not the participant ever developed an inhibitor to treatment, and bleeding disorder severity. For hemophilia A and B, severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe corresponding to 6 to 50%, 1 to 5%, and <1%, respectively, of the normal amount of clotting factor. VWD was classified as mild, moderate, or severe corresponding to Type I (lower than normal levels of von Willebrand factor), Type II (lower than normal levels and improper functioning of von Willebrand factor), and Type III disease (absence of von Willebrand factor in the blood).

Statistical analysis

Because of their skewed nature, descriptive statistics and univariate relationships were assessed by tabulating median PCS and MCS SF-36 scores with interquartile ranges (IQRs) by participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Percentages were used to describe categorical variables and statistical association with SF-36 scores was assessed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal Wallis test (depending on degrees of freedom), as they do not assume a normal distribution of the residuals. As part of an exploratory analysis, we also examined univariate relationships between participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and each of the eight SF-36 subscales. Because this portion of the analysis was only exploratory, no adjustments for multiple comparisons were made.

The primary outcome variables of interest (SF-36 PCS and MCS scores) were largely skewed, thus multivariable, quantile regression models were used to assess factors associated with physical and emotional SF-36 subscales. Factors assessed for their relationship with HRQoL included: age, gender, race and ethnicity, parent’s education level, bleeding disorder type and severity, history of inhibitor development, level of chronic pain, clotting-factor treatment adherence, and treatment regimen type (on-demand vs prophylactic). Due to the large number of variables collected as part of the survey and because of the small sample size inherent in rare disease research, in addition to the fully adjusted models, final parsimonious models were constructed. In the final parsimonious models, we decided, a priori, to include covariates in the model only if they (1) were statistically significant at a two-tailed alpha level of .05, (2) changed the coefficient of another statistically significant model parameter by at least 10% to 15% (i.e., confounded) [30], or (3) improved the precision of another statistically significant parameter already in the model. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC). All p-values were calculated using two-sided tests.

Results

Respondent characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 108 AYAs with hemophilia A, hemophilia B, and VWD participated; half of the participants were aged 13 to 17 years, and the majority were male (83%). Male participants were more likely to have hemophilia vs VWD (96 vs 4%), while the opposite was true for female participants (39 vs 61%). The majority (94%) of respondents had some type of health insurance.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics (n = 108)

| Characteristic | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 13–17 | 54 | 50 |

| 18–25 | 54 | 50 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 90 | 83 |

| Female | 18 | 17 |

| Race | ||

| White | 86 | 80 |

| Non-whitea | 22 | 20 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 12 | 11 |

| Non-Hispanic | 96 | 89 |

| Health insuranceb | ||

| Medicaid or VA onlyc | 34 | 32 |

| Commercial only | 46 | 43 |

| Both | 8 | 7 |

| Insured – type unknown | 12 | 11 |

| Uninsured | 6 | 6 |

| Mother’s education level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 38 | 35 |

| Less than Bachelor’s degree | 70 | 65 |

| Father’s education level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 31 | 29 |

| Less than Bachelor’s degree | 71 | 71 |

| Bleeding disorder | ||

| Hemophilia A | 85 | 79 |

| Hemophilia B | 5 | 7 |

| von Willebrand disease | 15 | 14 |

| Severity | ||

| Mild | 22 | 20 |

| Moderate | 9 | 8 |

| Severe | 77 | 71 |

| Inhibitor development | ||

| Ever | 38 | 35 |

| Never | 70 | 65 |

| Treatment regimen | ||

| On-demand | 35 | 32 |

| Prophylaxis | 73 | 68 |

| Chronic paind | ||

| None to mild | 74 | 69 |

| Moderate to severe | 34 | 31 |

| Clotting factor adherencee | ||

| Adherent | 77 | 71 |

| Non-adherent | 31 | 29 |

aMost (73%) of non-white respondents were black or African American, 14% were mixed race, 9% were Asian, and 5% were American Indian or Alaskan Native

bn = 78, two respondents answered ‘Don’t know’ as to whether or not they had health insurance, and were not included

cOnly two respondents had VA only insurance, the others had Medicaid only

dChronic pain was measured using the revised Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) and was dichotomized as FPS-R < 4 (i.e., ‘mild’ or ‘no pain) and FPS-R ≥4 (ie, ‘moderate’ to ‘worst pain possible’)

eAdherence was assessed using the Validated Hemophilia Regimen Treatment Adherence Scale (VERITAS)-Pro and VERITAS-PRN for prophylactic and on-demand participants, respectively. The cutoff for non-adherent prophylactic participants was a total VERITAS-Pro score ≥57 as established in previously by Duncan and colleagues [25]. This value was chosen because the VERITAS-Pro cutoff was approximately the 75th percentile of all responses

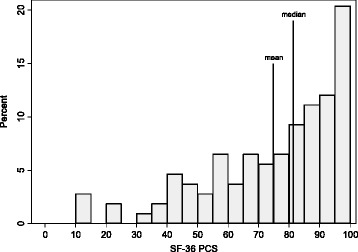

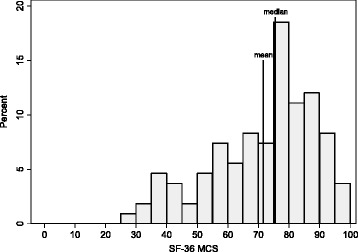

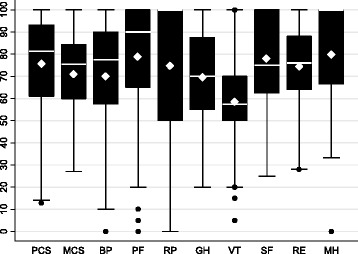

Median PCS and MCS were 81.3 (IQR: 61.1–93.1; range: 12.9–100) and 75.5 (IQR: 60.0–84.3.1; range: 27.1–100), respectively (Figs. 1 and 2). Mean values for PCS, MCS, and the eight multi-item subscales were generally lower than the median (with the exception of VT and SF) due to low outlying values (Fig. 3). At the univariate level, young adults (vs adolescents), non-whites, those who reported ever developing an inhibitor, and those who reported moderate to severe (vs none to mild) chronic pain had statistically significantly lower PCS scores (Table 2). Young adults (vs adolescents), those who reported moderate to severe (vs none to mild) chronic pain, and those who were non-adherent to prescribed clotting-factor treatment regimens had statistically significantly lower MCS scores (Table 2). Univariate level differences for PCS, MCS, and the eight multi-item subscales by respondent characteristic are shown in the supplement (Figs 4 and 5 for median and mean values, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of SF-36 Physical Component Summary scores (n = 108). SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; PCS, Physical Component Summary

Fig. 2.

Distribution of SF-36 Mental Component Summary scores (n = 108). SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; MCS, Mental Component Summary

Fig. 3.

Box plots for SF-36 component and subscale scores (n = 108). The solid white line represents median value, and the white diamond represents the mean value. PCS, Physical Component Summary score; MCS, Mental Component Summary; BP, bodily pain; PF, physical function; RP, role limitations due to physical health problems; GH, general health; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role limitations due to emotional problems; MH, emotional well-being/mental health

Table 2.

Median (IQR) SF-36 Physical and Mental Component Summary scores by respondent characteristic (n = 108)

| Characteristic | SF-36 PCS | p-value | SF-36 MCS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||

| 13–17 | 86.3 (64.8, 95.7) | 79.5 (64.6, 85.7) | ||

| 18–25 | 75.1 (59.0, 87.1) | 73.4 (58.6, 78.9) | ||

| Gender | 0.12 | 0.10 | ||

| Male | 83.0 (59.0, 94.5) | 76.8 (59.6, 85.7) | ||

| Female | 78.9 (64.8, 86.0) | 71.4 (64.6, 76.4) | ||

| Race | 0.02 | 0.94 | ||

| White | 83.6 (65.7, 94.3) | 75.9 (59.6, 84.3) | ||

| Non-whitea | 62.6 (48.3, 84.8) | 74.3 (64.6, 85.7) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.18 | 0.73 | ||

| Hispanic | 71.9 (59.3, 81.5) | 77.0 (67.0, 82.1) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 83.0 (61.1, 94.2) | 75.2 (59.6, 84.8) | ||

| Health insuranceb | 0.13 | 0.21 | ||

| Medicaid or VA onlyc | 79.4 (56.0, 86.4) | 75.9 (64.6, 85.7) | ||

| Commercial only | 86.2 (65.0, 95.7) | 78.8 (65.0, 84.3) | ||

| Both | 71.0 (60.8, 77.7) | 72.9 (59.3, 81.3) | ||

| Insured, type unknown | 83.7 (69.6, 91.8) | 64.3 (54.6, 86.3) | ||

| Uninsured | 63.0 (41.4, 90.5) | 61.8 (42.9, 69/3) | ||

| Mother’s education level | 0.19 | 0.71 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 86.1 (65.7, 95.5) | 75.7 (60.4, 85.4) | ||

| Less than Bachelor’s degree | 80.1 (58.1, 91.0) | 75.5 (59.6, 84.3) | ||

| Father’s education level | 0.10 | 0.46 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 88.3 (67.4, 95.5) | 76.4 (58.6, 87.1) | ||

| Less than Bachelor’s degree | 79.8 (58.1, 91.0) | 75.4 (60.4, 82.9) | ||

| Bleeding disorder | 0.78 | 0.34 | ||

| Hemophilia A | 81.2 (58.1, 94.5) | 76.4 (59.3, 85.7) | ||

| Hemophilia B | 81.7 (73.2, 88.5) | 76.1 (65.0, 81.8) | ||

| von Willebrand | 80.5 (64.8, 86.2) | 70.0 (64.6, 76.4) | ||

| Severity | 0.98 | 0.37 | ||

| Mild | 81.6 (65.0, 91.7) | 73.2 (61.8, 78.6) | ||

| Moderate | 86.0 (64.0, 88.6) | 75.4 (60.4, 87.1) | ||

| Severe | 79.8 (58.1, 94.3) | 76.4 (59.6, 85.7) | ||

| Inhibitor development | <0.01 | 0.16 | ||

| Ever | 69.0 (45.0, 85.2) | 73.4 (56.8, 83.9) | ||

| Never | 86.1 (67.9, 94.5) | 78.2 (64.6, 86.4) | ||

| Treatment regimen | 0.99 | 0.13 | ||

| On-demand | 81.9 (66.2, 91.7) | 72.9 (59.3, 78.9) | ||

| Prophylaxis | 81.2 (58.1, 94.5) | 77.1 (60.4, 85.7) | ||

| Chronic paind | <0.0001 | 0.01 | ||

| None to mild | 87.1 (75.5, 95.5) | 77.1 (64.6, 86.8) | ||

| Moderate to severe | 59.0 (45.0, 74.5) | 72.9 (56.8, 78.8) | ||

| Clotting factor adherencee | 0.24 | 0.04 | ||

| Adherent | 82.6 (64.8, 95.5) | 76.4 (64.6, 84.3) | ||

| Non-adherent | 79.0 (55.5, 90.5) | 68.2 (48.6, 78.6) |

aMost (73%) of non-white respondents were black or African American, 14% were mixed race, 9% were Asian, and 5% were American Indian or Alaskan Native

b n = 78, two participants answered ‘Don’t Know’ to whether or not they had health insurance and were not included

cOnly two participants had VA only insurance, the others had Medicaid only

dChronic Pain was measured using the revised Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) and was dichotomized as FPS-R < 4 (i.e., ‘mild’ or ‘no pain) and FPS-R ≥ 4 (i.e., ‘moderate’ to ‘worst pain possible’)

eAdherence was assessed using the Validated Hemophilia Regimen Treatment Adherence Scale (VERITAS)-Pro and VERITAS-PRN for prophylactic and on-demand participants, respectively. The cutoff for non-adherent prophylactic participants was a total VERITAS-Pro score ≥57, as established previously by Duncan and colleagues [25]. This value was chosen because the VERITAS-Pro cutoff was approximately the 75th percentile of all responses

SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, MCS Mental Component Summary, PCS Physical Component Summary

Final quantile regression models suggested that, compared with men, median PCS for women was 13.1 (95% CI: 2.4, 23.8; p = 0.02) points lower. Ever developing an inhibitor (vs never) was significantly associated with a 13.1 (95% CI: 4.7, 21.5; p < 0.01) point reduction in PCS. Prophylactic infusers (vs on-demand) had a 10.0 (95% CI: 0.7, 19.3; p = 0.04) point increase in median MCS. Compared with those with no or mild chronic pain, those with moderate to severe chronic pain had a 25.5 (95% CI: 17.2, 33.8; p < 0.001) and 10.0 (95% CI: 0.8, 19.2; p = 0.03) point reduction in median PCS and MCS, respectively. Tables 3 and 4 show final quantile regression models modeling PCS and MCS scores, respectively.

Table 3.

Quantile (median) regression model estimating median SF-36 Physical Component Summary scores, 2012 (n = 108)

| Characteristic | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.02 | |

| Female | −13.1 (−23.8, −2.4) | |

| Male | reference | |

| Inhibitor development | <0.01 | |

| Ever | −13.1 (−21.5, −4.7) | |

| Never | reference | |

| Chronic paina | <0.001 | |

| Moderate to severe | −25.5 (−33.8, −17.2) | |

| None to mild | reference |

aChronic pain was measured using the revised Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) and was dichotomized as FPS-R <4 (i.e., ‘mild’ or ‘no pain) and FPS-R ≥4 (i.e., ‘moderate’ to ‘worst pain possible’)

Table 4.

Quantile (median) regression model estimating median SF-36 Mental Component Summary scores, 2012 (n = 108)a

| Characteristic | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment regimen | 0.04 | |

| Prophylaxis | 10.0 (0.7, 19.3) | |

| On-demand | reference | |

| Chronic painb | 0.03 | |

| Moderate to severe | −10.0 (−19.2, −0.8) | |

| None to mild | reference |

aEthnicity (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic) and history of inhibitor development (ever vs never) were also included in the model, though not statistically significant, because they increased the precision of the estimates

bChronic pain was measured using the revised Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) and was dichotomized as FPS-R < 4 (i.e., ‘mild’ or ‘no pain) and FPS-R ≥ 4 (i.e., ‘moderate’ to ‘worst pain possible’)

CI confidence interval

Discussion

Evaluating HRQoL will be required to determine the effectiveness of care strategies and to measure the impact of living with a bleeding disorder over time. To our knowledge, limited data are available regarding the HRQoL of AYAs with hemophilia. In contrast to previous surveys, such as Hemophilia Experiences, Results and Opportunities (HERO), that assessed psychosocial issues in PWH [31–33], we assessed adherence using the validated VERITAS scale and used the SF-36 (vs the EuroQoL-5 dimensions [EQ-5D]) to assess HRQoL. The SF-36 assesses domains such as vitality and social functioning, which are not included in the EQ-5D [34]. Additionally, all patients in our study self-reported for assessments of QoL, whereas parents responded on behalf of children younger than 18 years in HERO [32]. Consistent with previous research in PWH among other age groups [35], AYA PWH or VWD who reported they had ever developed an inhibitor and those who reported moderate-to-severe chronic pain also reported worse physical HRQoL in this study. Previous reports suggest this finding is likely explained by the fact that most PWH report that pain interferes with daily activities and has a negative impact on their work. In addition to physical limitations in daily activity and work, prior research has suggested an emotional impact of chronic pain on quality of life as well [36, 37]. Witkop et al. demonstrated that one third of PWH report that pain impairs the ability to form close relationships and that nearly half of young adults with a bleeding disorder report being diagnosed with anxiety or depression [37]. It has been suggested that, in addition to emphasizing prophylaxis, interventions to promote acceptance of pain and to reduce negative thoughts about pain should be utilized when approaching PWH [15].

Adolescents had higher PCS and MCS scores compared to young adults, which may be related to more frequent disease-related bleeding and greater prevalence of chronic pain as individuals managing a bleeding disorder transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Previous research has underscored that adherence to treatment regimens declines with age. Diligent factor administration by parents in younger years often gives way to less treatment regimen fidelity during young adulthood where patients often begin to assume primary responsibility for their bleeding disorder care [22, 23, 38, 39]. Further, as children transition into young adulthood, their activity level often intensifies, which could heighten the risk of bleeding.

AYA females with a bleeding disorder reported lower physical HRQoL when compared with AYA men in this study, even after adjustment for other sociodemographic and clinical factors. Reasons for this are not clear. Previous work would suggest the opposite might be true given that, compared with AYA males, female AYA were more likely to have VWD (vs hemophilia) and that VWD, generally speaking, has a lower overall burden of disease than does hemophilia and is less commonly associated with the cumulative arthropathic burden in adulthood often seen in PWH [40]. However, approximately one in four patients with VWD experience joint bleeds, which can have a negative effect on physical quality of life, with the majority of first joint bleeds occurring before age 16 [40]. In addition, previous research has suggested that physical quality of life in female VWD patients may be affected by menorrhagia, dysmenorrhagia, or pregnancy-related bleeding, which could lead to anemia, fatigue, and pain [41–43]. Thus, in AYA, it is possible that acute bleeding and dysmenorrhea often associated with female VWD patients have a more immediate deleterious effect on HRQoL than do the long-term effects (e.g., arthropathy and hepatitis C) associated with hemophilia which may have not yet fully manifested. This interaction between age, sex, bleeding disorder type, and HRQoL should be more thoroughly evaluated with future research.

AYA patients who infused clotting factor prophylactically reported significantly better mental HRQoL (MCS) compared with those who infused using on-demand regimens. However, differences in physical HRQoL (PCS) were not observed in our study, which is a surprising finding given that prophylaxis is associated with fewer joint bleeds and less pain [7], and a recent review found that joint status was associated with both social and emotional well-being [44]. One possible explanation for the findings in our study is that physical sequelae of the disease have not yet manifested in AYAs, a hypothesis also set forth by Poon et al. [20]. However, prophylactic treatment may provide mental assurance to patients that their disease is well controlled, thereby leading to improved mental HRQoL. Future studies should attempt to tease out the influence of prophylaxis, disease type and severity, and comorbid illness on HRQoL.

This study has limitations. Primarily, data are cross-sectional, thus causal inference cannot be made. Specifically, although study results support that several factors (e.g., chronic pain, inhibitor development, clotting-factor regimen type) are related to HRQoL, the directionality of this relationship cannot be confirmed. That is, though we modeled how these factors affect HRQoL, it is also possible that HRQoL instead affects a patient’s willingness and ability to adequately manage his or her bleeding disorder. This cannot be teased out in a cross-sectional study and should be examined in the future with prospective studies. A second limitation is that all data are self-reported. As such, information about blood disorder type and severity, health insurance coverage, and other demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors are not confirmed by medical record review or administrative claims data. However, by obtaining data through self-report, this study was able to collect important, reliable, and valid patient-report outcomes (PRO) data about adherence, chronic pain, and HRQoL. Patient-reported data about pain and HRQoL are considered the ‘gold standard,’ and the VERITAS scales are the only validated measures of adherence to clotting-factor treatment developed to date.

Another limitation is that the VERITAS-combined score that we reported, though statistically comprised of two validated instruments, is an experimental, non-validated measure that has only been previously reported once [25]. Most participants (68%), however, treated prophylactically, and VERITAS-Pro scores, which have been previously validated, confirmed the results of the experimental, combined score. Additionally, the SF-36, used in this study to assess HRQoL, is only validated in persons aged 14 years and older [26], whereas a small percentage of patients in our study were aged 13 years (n = 9/108, 8.3%). Further, no comparisons were made between SF-36 results in study respondents versus matched normal controls or persons living with other chronic diseases. Finally, AYA PWH and VWD were primarily recruited from large national or regional hemophilia meetings. Thus, our convenience sample of AYA PWH and VWD may not adequately represent the broader AYA PWH and VWD population who do not typically attend these meetings.

Conclusions

Efforts should be made to prevent and manage chronic pain, which was strongly related to both physical and mental HRQoL, in the AYA PWH and VWD populations. Previous research has suggested that better adherence to prescribed treatment regimens is associated with less chronic pain [25]. Future research should explore (1) why women had lower physical HRQoL scores—even after adjustment for other sociodemographic and clinical factors, and (2) how prophylaxis may improve overall mental/emotional HRQoL in the AYA PWH and VWD populations.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support for formatting the manuscript as per journal requirements was provided by Teri ONeill at Peloton Advantage, and was funded by Pfizer Inc. This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. This study and manuscript were funded by Pfizer Inc. Pfizer employees were involved in the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the review of the manuscript, and the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Pfizer Inc but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Pfizer Inc.

Authors’ contributions

JMM, JEM, BT, AL and MLW contributed to the study design. JMM, JEM, AL and MLW participated in the collection and assembly of data. JMM, JEM, BT, AL and MLW participated in data analysis and interpretation. All authors participated in manuscript preparation, critically reviewed and provided revisions to the manuscript, and granted final approval of the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

Drs. McLaughlin, Anderson, and Tortella are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. Dr. Witkop and Mr. Munn have no conflicts of interest to report. At the time of this research, Mrs. Lambing had no conflicts of interest to report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the Munson Medical Center (Traverse City, MI) institutional review board prior to data collection. All authors have consented to the publication of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AYA

Adolescent and young adult

- BP

Bodily pain

- CI

Confidence interval

- EQ-5D

EuroQoL-5 dimensions

- FPS-R

Faces Pain Scale-Revised

- GH

General health

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- MCS

Mental Component Score

- MH

Emotional well-being/mental health

- PCS

Physical Component Score

- PF

Physical function

- PWH

Persons with hemophilia

- RE

Role limitations due to emotional problems

- RP

Role limitations due to physical health problems

- SF

Social functioning

- SF-36

36-Item Short Form Health Survey

- VT

Vitality

- VWD

von Willebrand disease

Contributor Information

John M. McLaughlin, Phone: 484-865-5489, Email: john.mclaughlin@pfizer.com

James E. Munn, Email: jmunn@med.umich.edu

Terry L. Anderson, Email: Terry.L.Anderson@pfizer.com

Angela Lambing, Email: Angela.lambing@bayer.com.

Bartholomew Tortella, Email: Bartholomew.J.Tortella@pfizer.com.

Michelle L. Witkop, Email: MWITKOP@mhc.net

References

- 1.Escobar MA. Advances in the treatment of inherited coagulation disorders. Haemophilia. 2013;19(5):648–59. doi: 10.1111/hae.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman RJ, Powell JS. Molecular approaches for improved clotting factors for hemophilia. Blood. 2013;122(22):3568–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-498261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lusher JM, Arkin S, Abildgaard CF, Schwartz RS. Recombinant factor VIII for the treatment of previously untreated patients with hemophilia a. Safety, efficacy, and development of inhibitors. Kogenate previously untreated patient study group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(7):453–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SL, High KA. Gene therapy for haemophilia. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(5):479–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franchini M, Mengoli C, Lippi G, Targher G, Montagnana M, Salvagno GL, et al. Immune tolerance with rituximab in congenital haemophilia with inhibitors: a systematic literature review based on individual patients’ analysis. Haemophilia. 2008;14(5):903–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gringeri A, Lundin B, von Mackensen S, Mantovani L, Mannucci PM, Group ES. A randomized clinical trial of prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A (the ESPRIT Study) J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(4):700–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manco-Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, Riske B, Hacker MR, Kilcoyne R, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(6):535–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Lofqvist T, Pettersson H. Twenty-five years’ experience of prophylactic treatment in severe haemophilia a and B. J Intern Med. 1992;232(1):25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evatt BL. The natural evolution of haemophilia care: developing and sustaining comprehensive care globally. Haemophilia. 2006;12(suppl 3):13–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoots WK. Comprehensive care for hemophilia and related inherited bleeding disorders: why it matters. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003;2(5):395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith PS, Levine PH. The benefits of comprehensive care of hemophilia: a five-year study of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(6):616–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.74.6.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soucie JM, Nuss R, Evatt B, Abdelhak A, Cowan L, Hill H, et al. Mortality among males with hemophilia: relations with source of medical care. The hemophilia surveillance system project investigators. Blood. 2000;96(2):437–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konkle BA. Clinical challenges within the aging hemophilia population. Thromb Res. 2011;127 Suppl 1:S10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scalone L, Mantovani LG, Mannucci PM, Gringeri A, Investigators CS. Quality of life is associated to the orthopaedic status in haemophilic patients with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2006;12(2):154–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elander J, Morris J, Robinson G. Pain coping and acceptance as longitudinal predictors of health-related quality of life among people with haemophilia-related joint pain. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(6):929–38. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gringeri A, Leissinger C, Cortesi PA, Jo H, Fusco F, Riva S, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with haemophilia and inhibitors on prophylaxis with anti-inhibitor complex concentrate: results from the Pro-FEIBA study. Haemophilia. 2013;19(5):736–43. doi: 10.1111/hae.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khair K. Supporting adherence and improving quality of life in haemophilia care. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(12):692. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.12.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SY, Kim SW, Kim JM, Shin IS, Baek HJ, Lee HS, et al. Impact of personality and depression on quality of life in patients with severe haemophilia in Korea. Haemophilia. 2013;19(5):e270–5. doi: 10.1111/hae.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondorf W, Kalnins W, Klamroth R. Patient-reported outcomes of 182 adults with severe haemophilia in Germany comparing prophylactic vs. On-demand replacement therapy. Haemophilia. 2013;19(4):558–63. doi: 10.1111/hae.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poon JL, Zhou ZY, Doctor JN, Wu J, Ullman MM, Ross C, et al. Quality of life in haemophilia a: hemophilia utilization group study Va (HUGS-Va) Haemophilia. 2012;18(5):699–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2012.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witkop M, Lambing A, Divine G, Kachalsky E, Rushlow D, Dinnen J. A national study of pain in the bleeding disorders community: a description of haemophilia pain. Haemophilia. 2012;18(3):e115–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrijvers LH, Uitslager N, Schuurmans MJ, Fischer K. Barriers and motivators of adherence to prophylactic treatment in haemophilia: a systematic review. Haemophilia. 2013;19(3):355–61. doi: 10.1111/hae.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindvall K, Colstrup L, Wollter IM, Klemenz G, Loogna K, Gronhaug S, et al. Compliance with treatment and understanding of own disease in patients with severe and moderate haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2006;12(1):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin JM, Lambing A, Witkop ML, Anderson TL, Munn J, Tortella B. Racial differences in chronic pain and quality of life among adolescents and young adults with moderate to severe hemophilia. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(1):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaughlin JM, Witkop ML, Lambing A, Anderson TL, Munn J, Tortella B. Better adherence to prescribed treatment regimen is related to less chronic pain among adolescents and young adults with moderate or severe haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(4):506–12. doi: 10.1111/hae.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan N, Kronenberger W, Roberson C, Shapiro A. VERITAS-Pro: a new measure of adherence to prophylactic regimens in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2010;16(2):247–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan NA, Kronenberger WG, Roberson CP, Shapiro AD. VERITAS-PRN: a new measure of adherence to episodic treatment regimens in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2010;16(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The faces pain scale-revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–83. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassis FR, Buzzi A, Forsyth A, Gregory M, Nugent D, Garrido C, et al. Haemophilia experiences, results and opportunities (HERO) study: influence of haemophilia on interpersonal relationships as reported by adults with haemophilia and parents of children with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(4):e287–95. doi: 10.1111/hae.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsyth AL, Gregory M, Nugent D, Garrido C, Pilgaard T, Cooper DL, et al. Haemophilia experiences, results and opportunities (HERO) study: survey methodology and population demographics. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):44–51. doi: 10.1111/hae.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nugent D, Kalnins W, Querol F, Gregory M, Pilgaard T, Cooper DL, et al. Haemophilia experiences, results and opportunities (HERO) study: treatment-related characteristics of the population. Haemophilia. 2015;21(1):e26–38. doi: 10.1111/hae.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joore M, Brunenberg D, Nelemans P, Wouters E, Kuijpers P, Honig A, et al. The impact of differences in EQ-5D and SF-6D utility scores on the acceptability of cost-utility ratios: results across five trial-based cost-utility studies. Value Health. 2010;13(2):222–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer K, van der Bom JG, van den Berg HM. Health-related quality of life as outcome parameter in haemophilia treatment. Haemophilia. 2003;9(suppl 1):75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.9.s1.13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elander J, Robinson G, Mitchell K, Morris J. An assessment of the relative influence of pain coping, negative thoughts about pain, and pain acceptance on health-related quality of life among people with hemophilia. Pain. 2009;145(1–2):169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witkop M, Guelcher C, Forsyth A, Hawk S, Curtis R, Kelley L, et al. Treatment outcomes, quality of life, and impact of hemophilia on young adults (aged 18–30 years) with hemophilia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(Suppl 2):S3–10. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.du Treil S, Rice J, Leissinger CA. Quantifying adherence to treatment and its relationship to quality of life in a well-characterized haemophilia population. Haemophilia. 2007;13(5):493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geraghty S, Dunkley T, Harrington C, Lindvall K, Maahs J, Sek J. Practice patterns in haemophilia A therapy -- global progress towards optimal care. Haemophilia. 2006;12(1):75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Galen KP, Sanders YV, Vojinovic U, Eikenboom J, Cnossen MH, Schutgens RE, et al. Joint bleeds in von Willebrand disease patients have significant impact on quality of life and joint integrity: a cross-sectional study. Haemophilia. 2015;21(3):e185–92. doi: 10.1111/hae.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Wee EM, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Van Der Bom JG, Degenaar-Dujardin ME, Eikenboom HC, Fijnvandraat K, et al. Health-related quality of life among adult patients with moderate and severe von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(7):1492–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kouides PA. Menorrhagia from a haematologist's point of view. Part I: initial evaluation. Haemophilia. 2002;8(3):330–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kouides PA, Phatak PD, Burkart P, Braggins C, Cox C, Bernstein Z, et al. Gynaecological and obstetrical morbidity in women with type I von Willebrand disease: results of a patient survey. Haemophilia. 2000;6(6):643–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2000.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elander J. A review of evidence about behavioural and psychological aspects of chronic joint pain among people with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(2):168–75. doi: 10.1111/hae.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Pfizer Inc but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Pfizer Inc.