Abstract

The association between the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk in offspring has been explored in several studies, but the result is still inconclusive. We assessed the risk of ASD in offspring in relation to ART by conducting a meta-analysis. A literature search in PubMed, Embase, and Web of Knowledge databases through April 30, 2016 was conducted to identify all the relevant records. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were computed to analyze the strength of association by using fixed- or random-effect models based on heterogeneity test in total and subgroup analyses. Analysis of the total 11 records (3 cohort studies and 8 case-control studies) revealed that the use of ART is associated with higher percentage of ASD (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.09–1.68, P = 0.007). In addition, subgroup analyses based on study design, study location and study quality were conducted, and some subgroups also showed a statistically significant association. Our study indicated that the use of ART may associated with higher risk of ASD in the offspring. However, further prospective, large, and high-quality studies are still required.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication, together with restricted and repetitive behavior1. Despite much effort made on the therapy of ASD and care system, it is still a major public health problem around the world. The prevalence estimates of ASD have dramatically increased in the last decades, as high as 1 person in 132 worldwide in 20102. Although the etiology of ASD remains uncertain, it is considered to be of multifactorial etiology, involving both genetic and environmental factors3,4. Therefore, there may be an important way to prevent ASD by identifying the causes of ASD. Recently, a number of studies have tried to explore the modifiable environmental risk factors of ASD. Among these risk factors, assisted reproductive technology (ART) was widely discussed because of its acceptability by more and more people.

Occurrence in pregnancy and birth factors have been indicated in the prevalence of ASD5,6,7. ART is used to achieve pregnancy and live birth through any procedure or medication trying to achieve pregnancy, including in vitro fertilization (IVF), zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), and artificial insemination among others. In vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are standardized ART treatments, and over 5 million children have been born by these procedures worldwide8. As ART has become increasingly common, the developmental outcomes of these pregnancies have been of concomitant concern. It has been reported that the use of ART increased the total risk of congenital malformations by about one-third, with approximately a twofold increased risk of nervous systems defects9. Accumulated evidence has suggested that the use of ART may lead to an increased risk of birth defects, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and genetic imprinting disorders10,11, which may account for the development of ASD. Several observational and epidemiological studies have explored the relationship of the use of ART and ASD risk in offspring, but the results were inconsistent. A recent systematic review by Conti et al. concluded that there is no significant association ART and ASD in offspring based on 7 observational studies12. The investigators pointed out that the studies selected are heterogeneous in many aspects including study design, definitions of ART, data source, and analyzed confounders. However, a study from Sandin et al. found that fresh embryo transfer ART procedures using ICSI for male factor infertility were associated with increased risk of autistic disorder and intellectual disability in offspring compared with fresh embryo transfer procedures without ICSI13. This is consistent with the finding from Kissin et al., who claimed that the children from pregnancies using ICSI are also at higher risk for the incidence of autism compared with conventional IVF14. Notably, it may be particularly important to adjust for parental characteristics because users of ART are more likely than fertile individuals both to be of increased age and to have chromosomal abnormalities.

Although these studies have proven to be informative, no study to date has concurrently examined the general risk of ASD in offspring in relation to their exposure to ART versus natural conception. Therefore, we performed this study to systematically assess the association of the use of ART and ASD risk.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

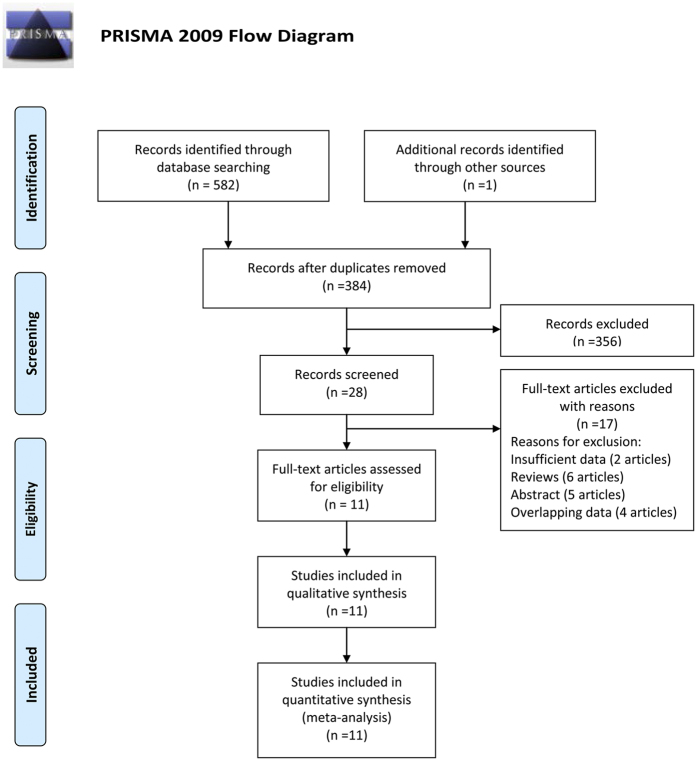

There were 572 records identified by using different search strategies in 3 databases (107 from PubMed, 265 from Embase, and 199 from Web of Knowledge) and 1 record by reference15. After removing 221 duplications and 323 unrelated records, 28 records were needed to further screen through full-text reading. Among the residual records, 13 records were excluded (2 records with insufficient data, 6 reviews, and 5 abstracts). Besides, there were 4 records16,17,18,19 excluded for overlapping data. Finally, 11 records15,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 (11 studies) were included in our meta-analysis (3 cohort studies and 8 case-control studies). The Flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study identification.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit http://www.prisma-statement.org.

All of the included studies were published during 2006–2015, including 3 cohort studies and 8 case–control studies. Among them, 4 studies were performed in Europe, 4 in America and 3 in Asia. In all, a total of 8,161,225 patients were included, of them 46249 with ASD (0.56%). The effect estimates of studies were extracted or calculated by the original data and the effect estimates in 6 studies were adjusted. The results of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale showed that 3 studies had the highest quality scores, 4 studies had moderate quality scores and 4 studies had low quality scores. The diagnosis in 10 studies was according to clinical evaluation and international coding. The characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author (year) | Country | Diagnosis | Study design | Source of the study population | Study period | ART type | Outcome | case/control | RR(95%CI) | Adjusted factors | methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Svahn et al. (2015)20 | Denmark | ICD-8/ICD-10 | cohort | The computerized Civil Registration System | 1969– | NA | ASD | 2058/2410663 | 1.06(0.99, 1.14) | year of birth, birth order, sex, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth and parental history of mental disorder | 8 |

| Kamowski-Shakibai et al. (2015)21 | USA | NA | case-control | Children in the New York tri-state area | NA | ART | ASD | 8/155 | 1.73(0.33, 9.08) | NA | 2 |

| Fountain et al. (2015)22 | USA | DSM-IV/code 299.0 | cohort | The California Birth Master Files for 1997–2007, the California DDS autism caseload records for 1997–2011, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National ART Surveillance System for live births for 1997–2007 | 1997–2007 | ART | ASD | 31243/5529810 | 1.71(1.55, 1.89) | year of birth, infant’s gender, and mother’s education and race | 6 |

| Sandin et al. (2013)23 | Sweden | ICD-9/ICD-10 | cohort | Swedish national registers | 1982–2009 | IVF with ICSI or without ICSI | autistic disorder | 6959/2541125 | 1.22(1.01, 1.49) | sex, attained age and birth year | 9 |

| Özbaran et al. (2013)24 | Turkey | DSM-IV/ADSI/WISC-R | case-control | The outpatient clinic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department of EUSM | NA | ART | Autism | 3/67 | 0.49(0.04, 5.61) | NA | 3 |

| Lehti et al. (2013)25 | Finland | ICD-9/ICD-10 | case-control | The Finnish Hospital Discharge Register | 1991–2007 | IVF | ASD | 4164/16582 | 0.9(0.70, 1.30) | maternal age and SES, gestational age and parity | 8 |

| Grether et al. (2013)26 | USA | ICD-9 | case-control | A KPNC facility | 1995–2002 | NA | ASD | 349/1847 | 0.99(0.67, 1.50) | maternal and paternal age, maternal race, maternal education, baby sex, gestational age, birth year, and birth facility | 6 |

| Lyall et al. (2012)27 | USA | ADI-R | case-control | Participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II | 1989– | ART | ASD | 507/2529 | 1.11(0.77, 1.62) | maternal and paternal age, race, income, and birth order | 6 |

| Shimada et al. (2012)15 | Japan | DSM-IV-TR | case-control | University of Tokyo Hospital/General Population of Tokyo | 2006–2009 | IVF; ICSI | ASD | 467/100118 | 1.84(1.18, 2.85) | NA | 2 |

| Zachor et al. (2011)28 | Israel | DSM-IV-TR | case-control | Large Israel population from infant registry of Rabin Medical Center | 1995–2002 | IVF and ICSI | ASD | 285/53080 | 2.78(1.81, 4.27) | NA | 2 |

| Stein et al. (2006)29 | Israel | ICD 8/DSM III/IV | case-control | ALUT center of Tel Aviv | 1970–1998 | Infertility requiring medical intervention | autism | 206/152 | 1.91(0.94, 3.88) | NA | 5 |

NA: no avalible; DDS: Department of Developmental Services; EUSM: Ege University School of Medicine.

Quantitative data synthesis

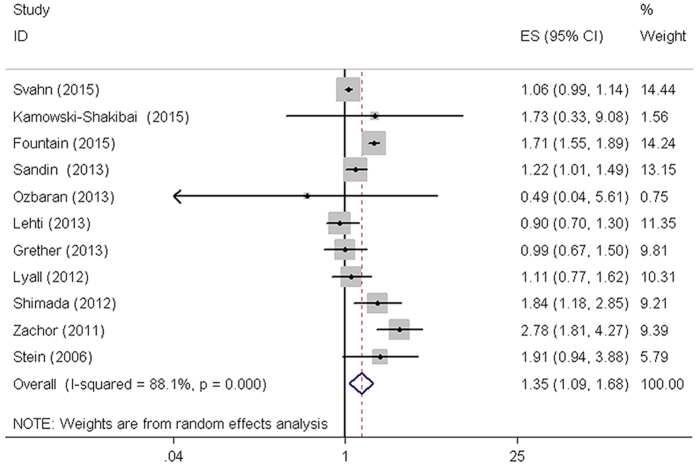

The effect of ART on the incidence of ASD was evaluated using the included studies. The overall results of our meta-analysis suggested that the use of ART may associated with higher percentage of ASD in children (RR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.09–1.68, P = 0.007) (Fig. 2, Table 2). In addition, subgroup analyses were conducted based on study design, study location, study quality, singletons birth, multiple birth and preterm (<37 weeks). There was a significant association between ART and the risk of ASD in European and Asian populations. The pooled RR based on 3 high quality studies showed that pregnancy by ART was associated with an increased risk of ASD. The results were shown in Table 2. Importantly, we found preterm delivery (<37 weeks) appear to be mediating factors in the ART-autism association. The results of singletons birth, multiple birth and preterm (<37 weeks) subgroups analysis were presented in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of ASDs risk associated with ART using. ASDs, autism spectrum disorders; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2. Summary of meta-analysis results.

| Groups | Studies | Test of association | Heterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR[95%CI] | p value | Model | Z | Χ2 | p value | I2(%) | ||

| Total studies | 11 | 1.35[1.09–1.68] | 0.007 | RE1 | 2.7 | 83.76 | 0 | 88.1 |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| study design | ||||||||

| cohort | 3 | 1.30[0.93–1.83] | 0.127 | RE | 1.52 | 59.36 | 0 | 96.6 |

| case-control | 8 | 1.40[0.99–1.98] | 0.06 | RE | 1.89 | 24.15 | 0.001 | 71 |

| scores | ||||||||

| high | 3 | 1.07[1.00–1.14] | 0.044 | FE2 | 2.02 | 3.02 | 0.221 | 33.7 |

| moderate | 4 | 1.36[0.98–1.90] | 0.07 | RE | 1.84 | 11.06 | 0.01 | 72.9 |

| low | 4 | 2.20[1.63–2.97] | 0 | FE | 5.16 | 3.27 | 0.352 | 8.3 |

| region | ||||||||

| America | 4 | 1.30[0.91–1.87] | 0.149 | RE | 1.44 | 10.85 | 0.013 | 72.4 |

| Europe | 3 | 1.07[1.00–1.14] | 0.044 | FE | 2.02 | 3.02 | 0.221 | 33.7 |

| Asia | 4 | 2.17[1.64–2.87] | 0 | FE | 5.42 | 3.33 | 0.343 | 10 |

| after removing three studies | 8 | 1.18[1.03–1.34] | 0.016 | FE | 2.41 | 10.25 | 0.175 | 31.7 |

RE: random effects; FE: fixed effects.

Heterogeneity analysis

Obvious between-study heterogeneity was shown in total analysis (I2 = 88.1%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2, Table 2). To explore the source of between-study heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses based on study design, study location, and study quality. However, heterogeneity across studies did not decrease effectively. Subsequently, Galbraith plot was conducted to graphically evaluate the sources of heterogeneity. Three studies20,22,28 were outside the bounds in Galbraith plot (Supplementary Figure S2), which were identified as the primary sources of our between-study heterogeneity. Once the 3 studies were removed, the heterogeneity decreased effectively (I2 = 31.7%, P > 0.001). Although no obvious heterogeneity was detected again among the remaining studies, the corresponding pooled RR changed little (RR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.03-1.34, P = 0.016) (Supplementary Figure S3). Therefore, ART may significantly increase the risk of ASD in children.

Sensitivity analysis

Each study was removed sequentially to verify the effect on our results of an individual study. The result of sensitivity analysis suggested that no obvious changes were found after excluded any study. Therefore, no individual study in our meta-analysis affected our pooled RR value statistically and our results were reliable (Data not shown).

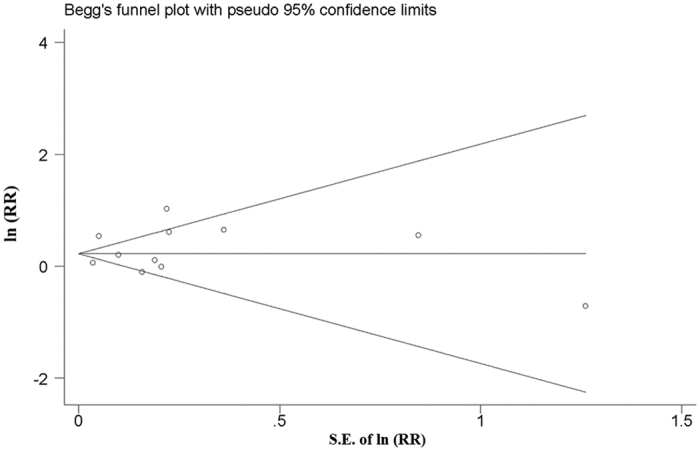

Publication bias

Both Egger’s and Begg’s methods were performed to explore the publication bias in our meta-analysis. Although slightly asymmetrical funnel plots were found in our results, there were no significant publication bias in our study (P = 0.755). The funnel plot was shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Funnel plots of studies examining the association between ASD and ART using. ASDs, autism spectrum disorders.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the association between the use of ART and the risk of ASD in offspring. In this meta-analysis, 8,161,225 patients were included. With the accumulating evidence, we have enhanced statistical power to provide more precise and reliable risk estimates. The most-relevant heterogeneity moderators have been identified by subgroup analysis. These findings are important in showing that ART may be an independent risk factor for ASD.

Consistent with our results, the majority of prior work suggests increased risks of autism, or developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and imprinting disorders with use of ART30,31. However, a handful of studies reported that the use of ART did not decrease the child outcomes32,33. This divergence may be due to the too small sample size during previous studies. We also did subgroup analysis based on study design, study location, and study quality. We have found a significant association between ART and the risk of ASD in European and Asian populations. And the pooled RR based on 3 high quality studies also showed that pregnancy by ART was associated with an increased risk of ASD. However, for the limitation of data, we could not conduct a subgroup analysis according to the method of ART (IVF/ICSI) according to the rationale. Only 1 record23 has reported different findings for fresh embryo transfer ART procedures using, versus not using, ICSI. It showed a statistically significantly increased risk for ASD after ICSI using surgically extracted sperm with fresh embryos, compared with those born after IVF without ICSI with fresh embryos.

As we found that ART may be an independent risk factor for ASD. A possible mechanism linking ART and ASD is epigenetic changes induced by repeated hormone exposure, semen preparation, freezing of embryos and gametes, use of culture media, growth conditions for embryos, and delayed insemination. Epigenetic mechanisms such as defects in genetic imprinting are increasingly recognized to play an important role in several neuropsychiatric disorders, such as Rett and Fragile X syndromes, characterized by autistic-like features in some patients34. Melnyk et al. found abnormal methylation is particularly involved in ART imprinting disorders related to the context of ASD35. Experiments in animals have suggested that the various steps of the ART procedures such as superovulation, in vitro culture of oocytes or embryo, and IVF might be related to epigenetic defects in the embryos and offspring36. However, abnormal DNA methylation could not be consistently identified in IVF children37. It seemed that ART procedures together with etiological factors, including reduced fertility of the parents or the advanced maternal and paternal age, impact the epigenetic DNA methylation state. Recent studies has found epigenetic variability in the male or female germline, and occurrence of age-related DNA-methylation changes in a number of genes, and those changes may contribute to the increased ASD risk in offspring of older parents38,39,40.

For many environmental factors associated with ASD, some authors reported the maternal age, parental infertility, multiple birth and preterm delivery (<37 weeks). All included studies, with the exception of 4 studies, take into account possible confounders. Seven studies adjusted the estimates by many factors, including year of birth, infant’s gender, and mother’s education. Maternal age was a common flaw in studies of prenatal exposures, but among the included studies, only 1 study analyzed the influence of maternal age on ASD22. It found that the risk of autism of was higher for children born to mothers aged 20 to 34, but the effect was reduced to null for the mothers aged 35 years or older. The reasons behind this difference require further investigation. Besides, a recent study found a significant association between a general category of infertility medications and ASD among multiple births, but did not find an association among singleton births41. For comparison to this work, we tried to examine exposures stratified by singleton and multiple birth. We found that in 3 of the 11 studies, singletons analysis separately and showed that no significant associations were found between IVF and ASD among both in all offspring group and singleton subgroup23,25,26. And 2 of the 11 studies have conducted the subgroup analysis of multiple birth22,26, showing no significant difference between all offspring group and multiple birth subgroup. Importantly, there were two studies which have analyzed the influence of preterm delivery (<37 weeks) on the ART-autism association22,23. And the subgroup analysis result suggested preterm delivery may be a mediating factor in the ART-autism association. But the mechanisms behind this association require further investigation.

Besides, obvious heterogeneity was found among studies of ART and ASD risk. In our study, we noted that there were no significant associations between ART and ASD risk when obvious heterogeneity was found in subgroups and analysis by random (DerSimonian-Laird) effects model. Additionally, 3 studies contributing to the heterogeneity across all included studies potentially confounded the analyses. When we removed these 3 studies, the corresponding pooled RR value with very few changes was stable and reliable. Still, these estimates have to be viewed with caution due to heterogeneity. Moreover, potential publication bias had an important influence on the analysis, but little evidence of publication bias was observed. Since only eligible studies in English language were included in this meta-analysis, additional research in other populations is warranted to support generalization of the findings.

There are several limitations in our study. First, the meta-analysis was insufficiently performed due to the limited number of studies, which restrict the strength and quality of evidence. Thereby, more studies should be included in future reviews, to provide further support for our results. Second, residual confounding is a concern. The complexity of ART treatment renders the identification of individual risk factors extremely challenging. Uncontrolled or unmeasured risk factors have the potential to produce biases. It is very difficult to obtain information about an individual aspect of ART treatment and its association with risk of ASD, the possibility cannot be ruled out that residual confounding affected the results. Third, in the present study, we cannot explain the specific biological mechanisms underlying the relationship between using ART and the risk of ASDs. Meanwhile, it is still difficult to rule out the effects of factors related to the underlying subfertility.

In summary, ART was associated with a significantly greater risk of ASD in the offspring. ART is likely to be an independent risk factor of ASD in offspring. Because the number of available studies is still limited, our findings should be taken with caution. More studies, in particular population-based prospective cohort studies, are needed to verify the impact of ART on ASD risk in children. In addition, to understand the strength of association, future studies exploring the underlying molecular mechanisms are needed.

Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis and systematic review protocol has been follow the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement.

Publication Search

All published articles were searched in the PubMed, Embase, and Web of Knowledge databases up to April 30, 2016. Key words were identified as followed: “autism”, “autistic”, “asperger syndrome” or “pervasive development disorders”; and “oocyte”, “fertilization”, “infertility”, “assisted reproductive technologies”, “intracytoplasmic sperm injection”, or “in vitro fertilization”. The search process was conducted by two independent investigators. All articles were retrieved and their references were checked to avoid missing other relevant articles. If data were not included in the original articles, we would contact related authors to obtain them.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies evaluating the association between ART and autism; (2) case–control or cohort studies; and (3) studies from which the effect estimates could be extracted or calculated from available data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies with insufficient data to calculate or extract effect estimates; (2) case report, review, comment, abstract, or animal studies. For studies with overlapping samples, only the one with the largest sample size was included.

Data Extract

Two independent researchers conducted data extraction to ensure the reliability of the results. Disagreement was resolved by discussion. The information of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was extracted using a standardized extraction form. Relevant information included the first author’s name, publication year, study country, study design, study period, diagnosis, data source, type of ART, the number of cases and controls, effect estimates and their corresponding 95% CI, and adjusted factors in the data analysis. If the effect estimates were not adjusted, we extracted a crude effect estimate. When the effect estimates were not presented in original studies, we calculate odds ratios or relative risk according to the data presented in the study.

Assessment of study quality

The quality of studies was evaluated by 2 independent reviewers according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, which contains 3 dimensions: selection, comparability, and exposure or outcome for case–control and cohort studies, respectively. Eight items were included to assess the quality of studies with a 9-star system. When the quality score of one study was greater than or equal to 7, we defined it as a high quality study, and we defined 0–3 stars and 4–6 stars, as low and moderate quality study, respectively42.

Statistical analysis

Since the absolute risk of autism was low, relative risks and their corresponding 95% confidence interval were used as summary statistics to evaluate the association between maternal ART and the risk of autism in our meta-analysis, and the other measures of association were expected to yield similar estimates of relative risk. Z-test was conducted to assess the statistical significance of pooled RRs. Besides, the results were combined using a generic inverse variance random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird) to calculate weights, where the weights depend on both within-study variance and the estimated between-study variance for random effects model. In addition to total analysis, we also carried out subgroup analyses based on study design, study location, and study quality. I-squared (I2) statistic and Chi-square based Q-test were used to investigate the heterogeneity across studies43. The selection of effects models was according to our heterogeneity test: P > 0.10 for the Q-test and I2 values less than 50% suggested no obvious heterogeneity across studies and a fixed (Mantel-Haenszel) effects model was applied; otherwise, a random (DerSimonian-Laird) effects model was used44. In addition, Galbraith plots were used to further explore the source of between-study heterogeneity. We also performed sensitive analysis by removing each included study in sequence to assess the stability of our results. Publication bias was evaluated via a funnel plot using both Egger’s45 and Begg’s46 methods. Statistical significance was defined when a p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: liu, L. et al. Association between assisted reproductive technology and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in the offspring: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 46207; doi: 10.1038/srep46207 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 31571069).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions X.T.F. conceived the study. L.L. and J.W.G. collected the data and drafted the manuscript. X.H., Y.L.C. and L.W. revised the manuscript and language.

References

- Posar A., Resca F. & Visconti P. Autism according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5(th) edition: The need for further improvements. Journal of pediatric neurosciences 10, 146–148 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A. J. et al. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychological medicine 45, 601–613 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P. J. What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Current opinion in pediatrics 22, 219–225 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhubi A., Cook E. H., Guidotti A. & Grayson D. R. Epigenetic mechanisms in autism spectrum disorder. International review of neurobiology 115, 203–244 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matelski L. & Van de Water J. Risk factors in autism: Thinking outside the brain. Journal of autoimmunity (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandin S. et al. Advancing maternal age is associated with increasing risk for autism: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 51, 477–486 e471 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movsas T. Z. et al. Autism spectrum disorder is associated with ventricular enlargement in a low birth weight population. The Journal of pediatrics 163, 73–78 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupka M. S. et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2010: results generated from European registers by ESHREdagger. Hum Reprod 29, 2099–2113 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J. et al. Assisted reproductive technology and risk of congenital malformations: a meta-analysis based on cohort studies. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 292, 777–798 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek K. D., Kirmeyer S. E., Martin J. A., Strobino D. M. & Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2009. Pediatrics 129, 338–348 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom L. N. & Segars J. Imprinting disorders and assisted reproductive technology. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity 17, 517–522 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti E., Mazzotti S., Calderoni S., Saviozzi I. & Guzzetta A. Are children born after assisted reproductive technology at increased risk of autism spectrum disorders? A systematic review. Hum Reprod 28, 3316–3327 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandin S., Nygren K. G., Iliadou A., Hultman C. M. & Reichenberg A. Autism and mental retardation among offspring born after in vitro fertilization. Jama 310, 75–84 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin D. M. et al. Association of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and parental infertility diagnosis with autism in ART-conceived children. Hum Reprod 30, 454–465 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T. et al. Parental age and assisted reproductive technology in autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and Tourette syndrome in a Japanese population. Res Autism Spec Dis 500–507 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Bay B., Mortensen E. L., Hvidtjorn D. & Kesmodel U. S. Fertility treatment and risk of childhood and adolescent mental disorders: register based cohort study. Bmj 347, f3978 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidtjorn D. et al. Risk of autism spectrum disorders in children born after assisted conception: a population-based follow-up study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 65, 497–502 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimburg R. D. & Væth M. Do children born after assisted conception have less risk of developing infantile autism? Human Reproduction 22, 1841–1843 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinborg A. et al. Neurological sequelae in twins born after assisted conception: controlled national cohort study. Bmj 329, 311 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svahn M. F. et al. Mental disorders in childhood and young adulthood among children born to women with fertility problems. Human Reproduction 30, 2129–2137 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamowski-Shakibai M. T., Magaldi N. & Kollia B. Parent-reported use of assisted reproduction technology, infertility, and incidence of autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 9, 77–95 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Fountain C. et al. Association Between Assisted Reproductive Technology Conception and Autism in California, 1997-2007. American Journal of Public Health 105, 963–971 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandin S., Nygren K. G., Iliadou A., Hultman C. M. & Reichenberg A. Autism and mental retardation among offspring born after in vitro fertilization. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 310, 75–84 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özbaran B. et al. Psychiatric evaluation of children born with assisted reproductive technologies and their mothers: A clinical study. Noropsikiyatri Arsivi 50, 59–64 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lehti V. et al. Autism spectrum disorders in IVF children: A national case-control study in Finland. Human Reproduction 28, 812–818 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grether J. K. et al. Is infertility associated with childhood autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43, 663–672 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall K., Pauls D. L., Spiegelman D., Santangelo S. L. & Ascherio A. Fertility therapies, infertilityand autism spectrum disorders in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 26, 361–372 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachor D. A. & Ben Itzchak E. Assisted reproductive technology and risk for autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities 32, 2950–2956 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D., Weizman A., Ring A. & Barak Y. Obstetric complications in individuals diagnosed with autism and in healthy controls. Comprehensive psychiatry 47, 69–75, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidtjorn D. et al. Cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and developmental delay in children born after assisted conception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163, 72–83 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg B. et al. Neurological sequelae in children born after in-vitro fertilisation: a population-based study. Lancet 359, 461–465 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall K., Baker A., Hertz-Picciotto I. & Walker C. K. Infertility and its treatments in association with autism spectrum disorders: a review and results from the CHARGE study. International journal of environmental research and public health 10, 3715–3734 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A. et al. Increased risk of psychiatric disorders in children born to women with fertility problems: Results from a large Danish population-based cohort study. Human Reproduction 29, i28 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loke Y. J., Hannan A. J. & Craig J. M. The Role of Epigenetic Change in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Frontiers in neurology 6, 107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk S. et al. Metabolic imbalance associated with methylation dysregulation and oxidative damage in children with autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 42, 367–377 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman S. R., Pak Y. & Rivera R. M. Superovulation induces alterations in the epigenome of zygotes, and results in differences in gene expression at the blastocyst stage in mice. Molecular reproduction and development 82, 207–217 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman S., Wenegrat J., Rettew D., Althoff R. & Bernier R. No increase in autism-associated genetic events in children conceived by assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril 102, 388–393 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan J. M. et al. Intra- and interindividual epigenetic variation in human germ cells. American journal of human genetics 79, 67–84 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins T. G., Aston K. I., Pflueger C., Cairns B. R. & Carrell D. T. Age-associated sperm DNA methylation alterations: possible implications in offspring disease susceptibility. PLoS Genet 10, e1004458 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsem S. et al. Paternal age effects on sperm FOXK1 and KCNA7 methylation and transmission into the next generation. Hum Mol Genet (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grether J. K. et al. Is infertility associated with childhood autism? J Autism Dev Disord 43, 663–672 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Yang Z. & Zhong R. Primary biliary cirrhosis and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 56, 1409–1417 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J. & Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 327, 557–560 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M. & Higgins J. P. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prevention science: the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research 14, 134–143 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M. & Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj 315, 629–634 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C. B. & Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.