Abstract

Darier’s disease (DD) is an autosomal dominantly inherited skin disorder caused by mutations in SERCA2, a Ca2+ pump that transports Ca2+ from the cytosol to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Loss of desmosomes and keratinocyte cohesion is a characteristic feature of DD. Desmosomal cadherins (DC) are Ca2+-dependent transmembrane adhesion proteins of desmosomes, which are mislocalized in the lesional but not perilesional skin of DD. We show here that inhibition of SERCA2 by two distinct inhibitors results in accumulation of DC precursors in keratinocytes, indicating ER-to-Golgi transport of nascent DC is blocked. Partial loss of SERCA2 by siRNA has no such effect, implicating that haploinsufficiency is not sufficient to affect nascent DC maturation. However, a synergistic effect is revealed between SERCA2 siRNA and an ineffective dose of SERCA2 inhibitor, and between an agonist of the ER Ca2+ release channel and SERCA2 inhibitor. These results suggest that reduction of ER Ca2+ below a critical level causes ER retention of nascent DC. Moreover, colocalization of DC with ER calnexin is detected in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes and DD epidermis. Collectively, our data demonstrate that loss of SERCA2 impairs ER-to-Golgi transport of nascent DC, which may contribute to DD pathogenesis.

Keywords: SERCA2 calcium pump, desmosomal cadherins, ER-to-Golgi blockade, desmosomal adhesion, Darier disease, keratinocytes

Introduction

Desmosomes are intercellular adhesive junctions that play a key role in maintaining the cohesion of keratinocytes and the integrity of the epidermis 1,2. Desmosomal adhesion is mediated by desmosomal cadherins (DC) through their ectodomain interactions. Intracellularly, the cytoplasmic domains of DC interact with plakoglobin (PG) and plakophilins, which in turn bind to desmoplakin (DP). DP links desmosomes to intermediate filaments 3. DC, including desmoglein (Dsg) and desmocollin (Dsc), are transmembrane adhesion proteins that belong to the cadherin family. In humans there are four Dsg isoforms (Dsg1-4) and three Dsc isoforms (Dsc1-3), which are expressed in a tissue-dependent and spatially-regulated manner 4.

Darier’s disease (DD) is a rare autosomal dominantly inherited skin disorder characterized by hyperkeratotic papules or plaques that are predominantly located in the seborrheic areas of the face, chest, and trunk 5. Disease onset is usually around puberty and the severity of symptoms varies among patients, ranging from subtle, mild, to severe. Many patients have neuropsychiatric symptoms 6. Histological hallmarks of DD include hyperkeratosis (thickening of the outermost dead layer of the skin), dyskeratosis (premature keratinization), focal acantholysis (loss of cohesions between keratinocytes), and suprabasal clefting 7,8. Loss of desmosomes 9 and mislocalization of DP and DC 10–13 are seen in lesional but not perilesional skin of DD. The defective gene in DD is ATP2A2 14, which encodes the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) isoform 2. SERCA2 is the only isoform of SERCA family members that is expressed in keratinocytes 15. SERCA is a calcium pump that actively transports Ca2+ from the cytosol to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) against a concentration gradient 16. The primary consequence of SERCA dysfunction is reduced Ca2+ content in the ER and increased Ca2+ level in the cytosol 17,18. However, the specific role of SERCA2 in desmosomal adhesion is not well understood.

Impaired translocation of DP to the cell borders has been observed in cultured DD keratinocytes 19, SERCA2 siRNA-transfected normal keratinocytes 20, and SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin (TG)-treated cells 17,19,21. Hobbs et al. shows that siRNA knockdown of SERCA2 results in attenuated protein kinase C alpha signaling, which increases DP retention along keratin filaments and thus delays DP translocation to the cell borders 20. SERCA2 inhibition has also been shown to upregulate sphingosine production, which in turn affects the cell border localization of DP and E-cadherin via a yet unknown mechanism 21.

Impaired trafficking of DC to the cell border has also been detected in keratinocytes treated with TG; however, in DD keratinocytes that were derived from unaffected skin of patients, DC trafficking was only slightly affected 19. A recent study by Savignac et al. has detected some degree of ER stress response in DD keratinocyte culture 22. A small portion of DC and E-cadherin was observed in the perinuclear region, which was partially colocalized with ER calnexin, indicative of ER retention 22. However, whether SERCA2 deficiency can cause ER retention of DC remains to be determined because an earlier study from the same research group has shown that treatment of keratinocytes with TG affects neither DC glycosylation nor their gel mobility 19. The study by Dhitavat et al. 19 contradicts the notion of ER retention 22, as post-ER processing of DC is expected to be affected if DC are retained in the ER. Here we provide the first biochemical evidence that inhibition of SERCA2 impairs post-ER maturation of DC, demonstrating that SERCA2 activity is crucial for ER-to-Golgi transport of DC precursors.

Results

Inhibition of SERCA2 impedes the transport of newly synthesized DC to the plasma membrane

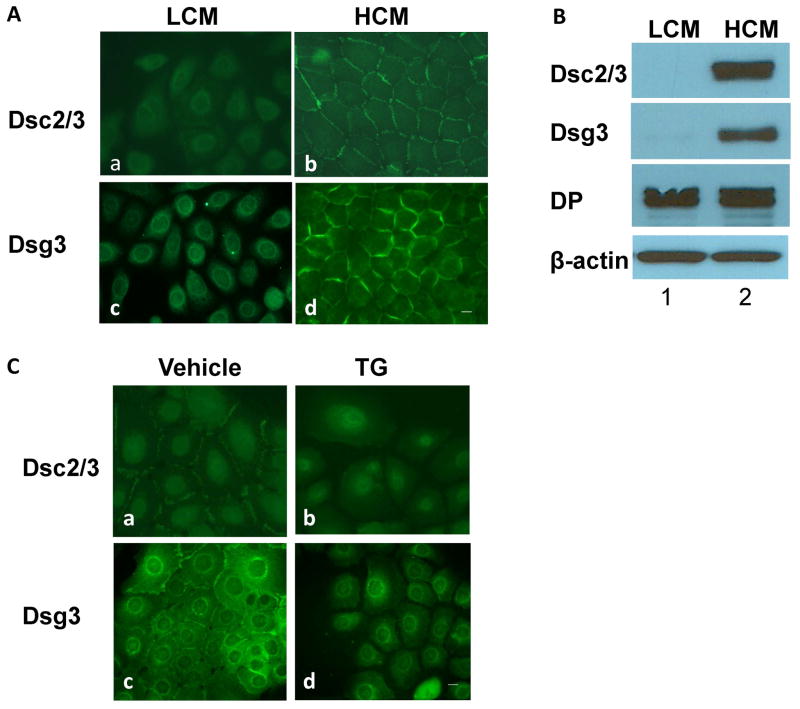

Desmosomes are not assembled when epithelial cells are cultured in low calcium media (LCM), but they are assembled upon switching cells to high calcium media (HCM) 23,24. Under LCM conditions, Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) are not detected on cell borders, but weak staining is revealed in the perinuclear regions (Fig. 1A). Western blotting (WB) shows that the steady-state levels of Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 in NHEK cultured in LCM are extremely low (Fig. 1B, lane 1), showing very weak bands when overexposed (data not shown). By sharp contrast, significant amounts of Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 are detected following overnight culture in HCM (Fig. 1B, lane2). Unlike DC, the steady-state level of DP is similar in both LCM and HCM (Fig. 1B). These results are consistent with the findings from MDCK cells, where the turnover rates of DGII/III (Dsc) and DGI (Dsg) are very rapid in LCM (T1/2 < 4 h) compared to those in HCM (T1/2 > 20 h) 25,26. We took advantage of this observation and used the calcium-induction method to assess the effect of SERCA2 inhibition on newly synthesized DC. At the time of HCM switch, we treated NHEK with control vehicle or TG, a highly specific and irreversible inhibitor of SERCA that has been widely used to study the consequences of ER Ca2+ depletion 27. The results show that TG treatment blocks Ca2+-induced transport of Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 to the cell borders (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with the results by Dhitavat et al. 19.

Figure 1. Newly synthesized DC do not transport to the plasma membrane when SERCA2 is inhibited.

NHEK were cultured to subconfluence in LCM (0.06 mM) and switched to HCM (1.2 mM) medium overnight. Cells were subjected to IF staining (A) or WB analysis (B). C) Subconfluent NHEK cultured in LCM were switched to HCM in the presence of SERCA inhibitor TG (0.1 μM) or vehicle for 6 hours followed by IF staining. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Inhibition of SERCA2 alters electrophoretic mobility of DC

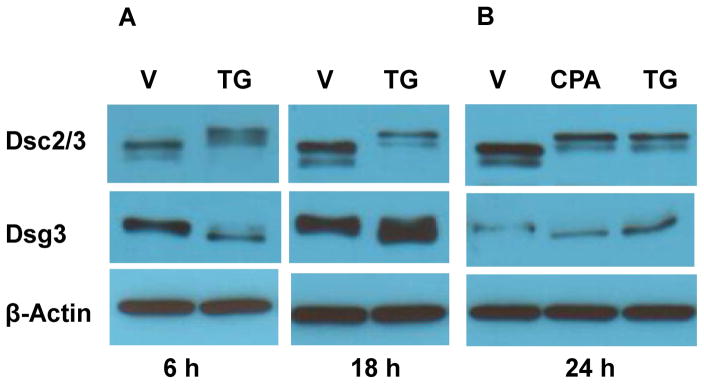

We then analyzed DC by WB. Compared to control cells treated with vehicle, Dsc2/3 from TG-treated cells migrate much more slowly (Fig. 2A, upper panels), whereas Dsg3 migrates slightly faster (Fig. 2A, middle panels). These results were unexpected because a previous study has shown that DC mobility was not affected by TG treatment 19. To confirm the results, we examined the effects of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), a structurally distinct SERCA inhibitor that is less potent and reversible 28. We observed identical mobility-shifted Dsc2/3 (Fig. 2B, upper panels) and Dsg3 (Fig. 2B, middle panels) from cells treated with CPA and TG.

Figure 2. Alteration of electrophoretic mobility in DC.

WB analysis of SDS lysates from NHEK treated with SERCA inhibitors TG (0.1 μM) or CPA (20 μM ) (A–B), transfected with SERCA2 (SER si) or control non-targeting (Ctl si) siRNA (C), treated with various doses of TG as indicated (D), treated with an ineffective dose of TG (5 nM) along with or without CMC (100 μM) (E), or transfected with siRNA with or without the ineffective dose of TG (5 nM) (F). The treatments were 24 h.

Partial loss of SERCA2 by siRNA does not affect DC mobility, but has a synergistic effect with an ineffective dose of TG

We next examined the effects of SERCA2 deficiency in keratinocytes by silencing SERCA2 expression. As shown in Fig. 2C, SERCA2 level is dramatically reduced in cells transfected with SERCA2 siRNA; however, the gel mobility of Dsc2/3 is not affected. We speculated that alteration of Dsc2/3 mobility is caused by ER Ca2+ reduction to a critical level, and that partial loss of SERCA2 function by siRNA may not be sufficient to reduce ER Ca2+ content to that threshold level. To test this possibility, we first titrated the dose of TG. The results show that TG at 5 nM is ineffective, but is effective at the dose of 25 nM or higher (Fig. 2D). At the dose of 10 nM, both the normal and the slow migrating bands of Dsc2/3 are detected (data not shown). We therefore treated cells with the ineffective dose of TG (5 nM) in conjunction with 4-chloro-m-cresol (CMC), a specific agonist of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) that stimulates Ca2+ leak from the ER under rest conditions 29,30. The result shows that stimulation of RyRs alone does not affect Dsc2/3 mobility but synergistically affects Dsc2/3 with an ineffective dose of TG (Fig. 2E), supporting our hypothesis that alteration of Dsc2/3 mobility is caused by ER Ca2+ reduction. We next examined the combining effects of SERCA2 silencing with an ineffective dose of TG (5 nM) and the result shows a synergistic effect on Dsc2/3 gel mobility (Fig. 2F). Together, these data indicate that DC mobility change is a consequence of ER Ca2+ reduction below a threshold level.

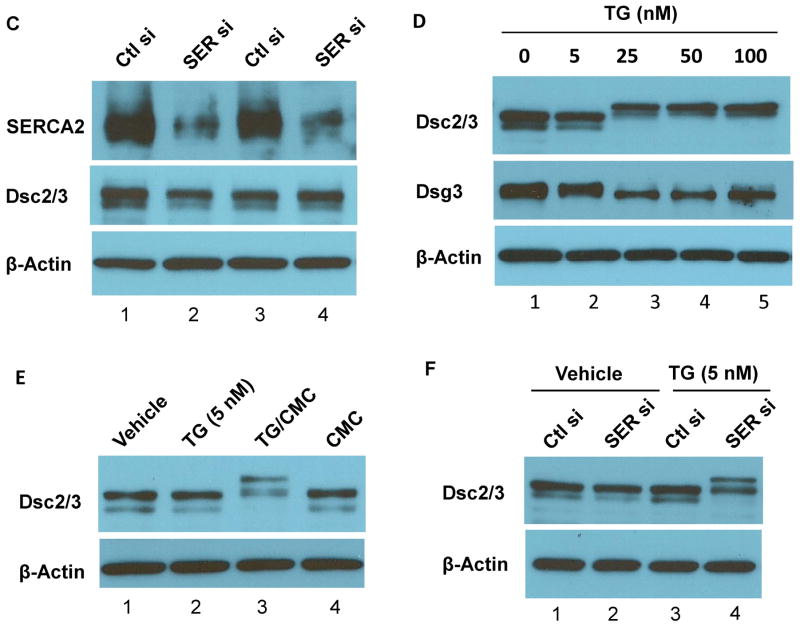

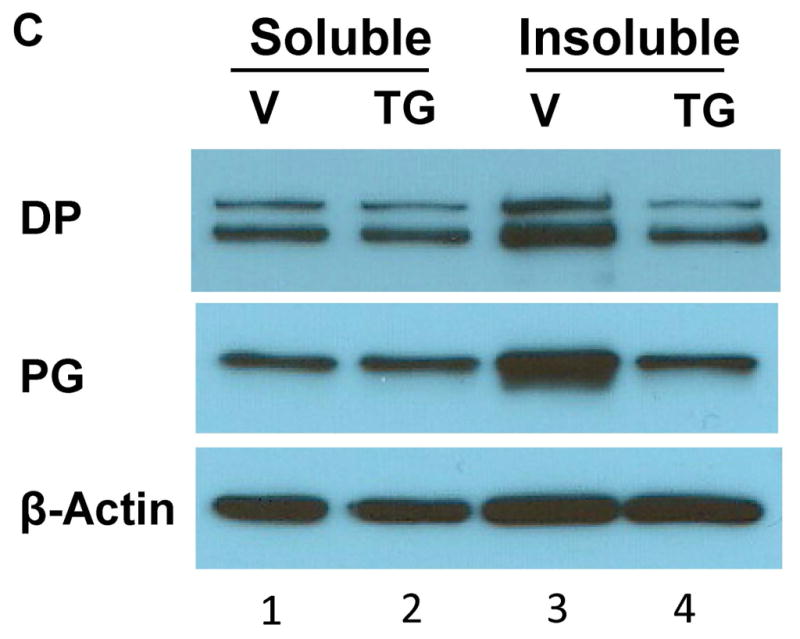

Mobility-shifted DC are soluble in Triton X-100

Given the fact that newly synthesized Dsc precursor migrates at a slower rate on SDS-PAGE than its mature form 31,32, whereas Dsg precursor migrates slightly faster than its mature form 31, we speculated that the mobility-shifted DC are their immature precursors. As immature DC are soluble in non-ionic detergent, whereas mature DC are largely insoluble 26,33, we examined the solubility of DC in Triton X-100. Following overnight calcium switch in the presence of vehicle (V) or SERCA inhibitors (TG or CPA), cells were extracted into 1% Triton X-100 soluble and insoluble fractions and subjected to WB analysis (Fig. 3). In control cells, Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 are predominantly present in the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction (Fig. 3A and 3B, compare lanes 1 and 3). By sharp contrast, in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes (TG, CPA), the slower migrating Dsc2/3 is present only in the Triton X-100 soluble fraction, and no Dsc2/3 is present in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 3A and 3B, upper panels, lanes 2 vs. 4). Similarly, the slightly faster migrating Dsg3 derived from SERCA2-inhibited (TG or CPA) keratinocytes is present only in the soluble fraction, and absent in the insoluble fraction. (Fig. 3A and 3B, middle panels, lanes 2 vs. 4). These results show that the solubility of the mobility-shifted DC is consistent with the character features of their precursors.

Figure 3. Triton X-100 solubility of DC and desmosomal plaque proteins.

NHEK were treated with vehicle (V) or SERCA blockers TG (0.1 μM) or CPA (20 μM) for 24 h. Cells were then extracted with Triton X-100 lysis buffer. Insoluble pellet was solubilized in SDS lysis buffer. Samples were subjected to WB analysis using antibodies as indicated. A) and B) Solubility of DC. Mobility-shifted DC from SERCA2-inhibited NHEK are presented only in the soluble (lane 2) and not in the insoluble fraction (lane 4), whereas DC from control cells are largely insoluble (compare lanes 1 and 3). Notably, in SERCA2-inhibited NHEK a small fraction of Dsg3 with normal mobility is revealed in the insoluble pool (lane 4), whereas the faster migrating Dsg3 is in the soluble pool (lane 2). C) Solubility of desmosomal plaque proteins. TG treatment causes reduced levels of DP and PG in the insoluble fraction (compare lanes 3 and 4).

Loss of SERCA2 activity does not cause abnormal aggregates of desmosomal proteins

We also examined the solubility of desmosomal plaque proteins (Fig. 3C). The results show that in control cells, more DP and PG are present in the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction than in the soluble fraction (lanes 1 vs. 3). Following SERCA2 inhibition, the distribution of DP and PG in the Triton X-100 soluble fraction is not affected (compare lanes 1 and 2), but their levels in the insoluble fraction are reduced (compare lanes 3 and 4). Together with the solubility of DC shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, our data show that inhibition of SERCA2 reduces the insolubility of desmosomal proteins, which is against the notion that loss of SERCA2 activity causes abnormal aggregates of desmosomal proteins 19.

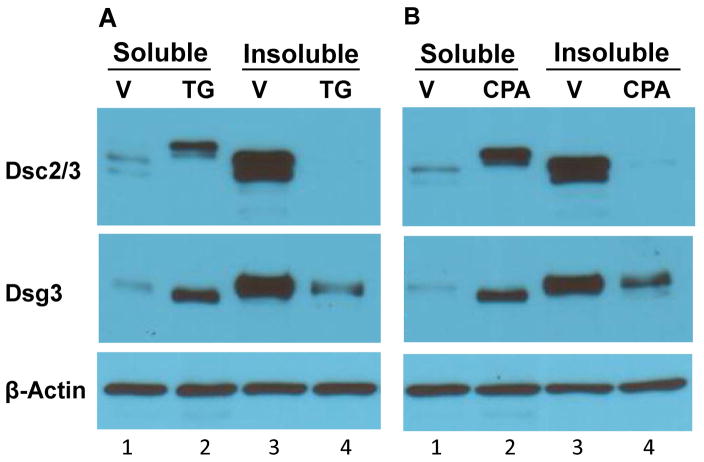

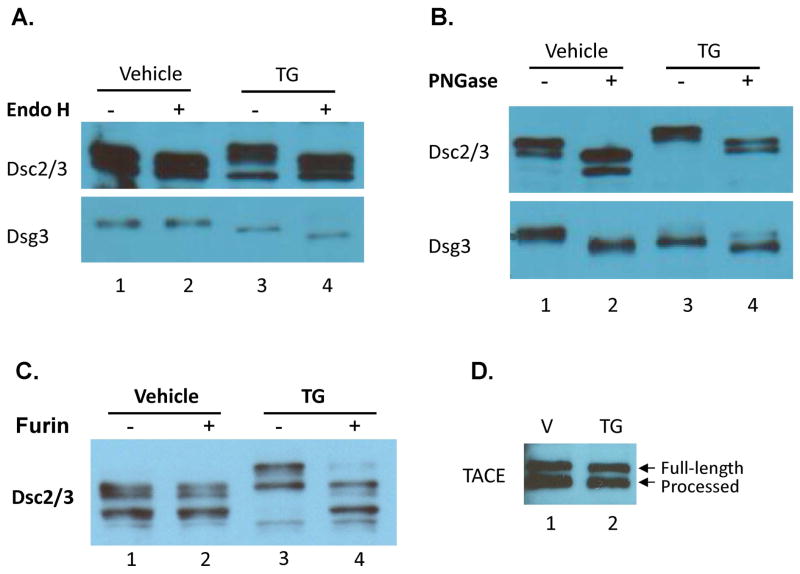

Loss of SERCA2 function affects N-glycosylation of DC

Earlier pulse-chase experiments have demonstrated that DC precursors carry the high-mannose type N-glycans, which are processed to the complex type after being transported to the Golgi complex 26,31. To confirm that the mobility-shifted DC are their precursors, we tested their sensitivity to Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H), which removes the N-linked high-mannose carbohydrate moieties but not the complex type. The results show that mature Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 from control cells are resistant to Endo H digestion (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, the slower migrating Dsc2/3 and the slightly faster migrating Dsg3 from TG treated cells are sensitive to Endo H digestion (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 4), demonstrating that their N-glycans are of the high-mannose type. We also digested the same set of samples with peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F), which removes both the complex and the high-mannose carbohydrates and produces non-glycosylated proteins. Fig. 4B shows that the molecular mass of Dsc2/3 and Dsg3 from both vehicle-treated and TG-treated cells is reduced following PNGase F digestion, indicating the presence of N-glycans in Endo H-resistant DC from control cells. These data demonstrate that the terminal processing of N-glycans of DC from the high-mannose to the complex type is blocked in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes, indicating the blockade of ER-to-Golgi transport of DC precursors. Our results contradict the results by Dhitavat et al. that DC glycosylation was not affected by TG treatment 19.

Figure 4. TG-induced mobility-shifted DC are sensitive to Endo H and proprotein convertase whereas maturation of TACE is not affected by TG treatment.

NHEK were treated with TG (0.1 μM) or vehicle for 24 h. Cell lysates were digested with or without Endo H (A), with or without PNGase (B), and with or without furin (C), followed by WB analysis. The presence of mature (processed) TACE in keratinocytes that were treated with TG (0.1 μM for 24 h) is detected by WB (D).

Loss of SERCA2 blocks the cleavage of the prodomain of DC

Dsc and Dsg precursors are known to contain a large prodomain (~10 kDa) 31 and a small prodomain (~3 kDa) 34, respectively. For proof-of-concept, we tested the sensitivity of Dsc2/3 to furin, a human proprotein convertase that is able to cleave the prodomain of many proproteins including recombinant Dsg precursors 35–37. As shown in Fig. 4C, furin digestion of the TG-treated keratinocyte lysates reduces the molecular mass of Dsc2/3 (compare lanes 3 and 4), demonstrating the presence of a large prodomain (~10 kDa). As expected, mature Dsc2/3 from control cells is resistant to furin digestion (compare lanes 1 and 2). Following prodomain cleavage, immature Dsc2/3 that carries the high-mannose type N-glycans shows a similar gel mobility as mature Dsc2/3 that harbors the complex type N-glycans (compare lane 4 and lanes 1, 2). This result indicates that the mass of both the complex and the high-mannose type N-glycans, on mature and immature Dsc2/3 respectively, is similar to the mass of the prodomain (~10 kDa). This is supported by the size difference between the glycosylated and non-glycosylated mature Dsc2/3 or immature Dsc2/3 shown in Fig. 4B (compare lanes 1 and 2; lanes 3 and 4). Nevertheless, the results shown in Fig. 4C further demonstrates that inhibition of SERCA2 in keratinocytes blocks the ER-to-Golgi transport of Dsc2/3 precursor, as proteolytic removal of a prodomain of proproteins occurs in the trans Golgi network-endosomal compartments 38.

Loss of SERCA2 does not block post-translational processing of tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme (TACE)

TACE or ADAM17, is a transmembrane shedding enzyme that is expressed as the full-length precursor form and processed form in many type of cells including keratinocytes 39,40. To evaluate whether inhibition of SERCA2 in keratinocytes has a general blocking effect on ER-to-Golgi transport of the secretary pathway proteins, we analyzed the presence of the processed and unprocessed forms of TACE in TG-treated NHEK by WB. The data show similar levels of the two forms of TACE in TG-treated and vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4D). This result demonstrates that the transport of TACE from the ER to the Golgi complex is not affected in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes, as the processed form of TACE is a result of proteolytic cleavage of the prodomain of TACE that takes place in the Golgi compartments 40.

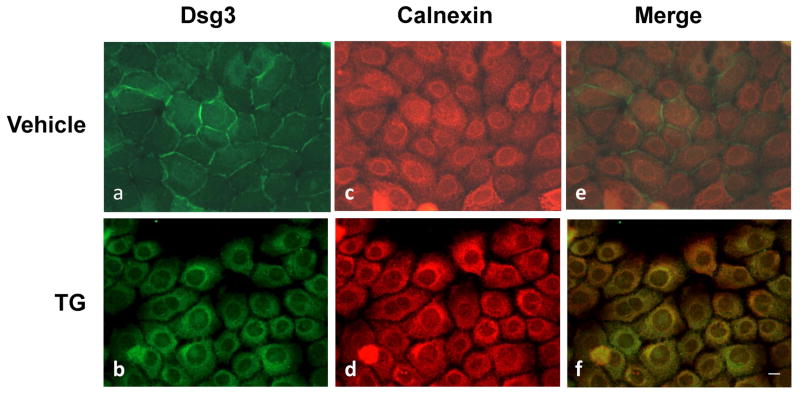

Dsg3 is retained in the ER following SERCA2 inhibition

Our biochemical analysis demonstrates that inhibition of SERCA2 in keratinocytes results in accumulation of DC precursors, suggesting that newly synthesized DC are trapped in the ER and fail to transport to the Golgi complex for N-glycan processing, prodomain cleavage, and insoluble pool entrance. To further verify this conclusion, we evaluated the subcellular localization of Dsg3 and an ER-resident protein chaperone calnexin by dual-labeling immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy. In control keratinocytes treated with vehicle, Dsg3 is distributed along the cell borders whereas calnexin is revealed in the perinuclear areas (Fig. 5, top panels). However, in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes, the subcellular distribution of Dsg3 is very similar to that of ER calnexin (panel b vs d), suggesting ER retention of Dsg3. Moreover, partial colocalization of Dsg3 with calnexin is revealed in the merged image (yellow signals in panel d), suggesting their interactions. These IF staining results, together with the biochemical characterization data, strongly suggest that nascent precursors of DC fail to exit the ER when SERCA2 activity is inhibited in keratinocytes. Interestingly, TG treatment seems to also affect the subcellular distribution of ER calnexin, which often exhibits an enhanced perinuclear localization (Fig. 5, panel d). However, WB analysis shows no changes in its total expression level (data not shown).

Figure 5. ER retention of Dsg3 in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes.

Following TG (0.1 μM) exposure and overnight calcium switch, cells were fixed and subjected to dual-IF staining with Dsg3 and ER calnexin. In contrast to vehicle-treated control cells (a and c), the staining pattern of Dsg3 (green) and calnexin (red) is very similar in TG-treated cells (b and d). Colocalization of Dsg3 and calnexin (yellow signal) is revealed by merging the two images (f). Scale bar = 10 μm.

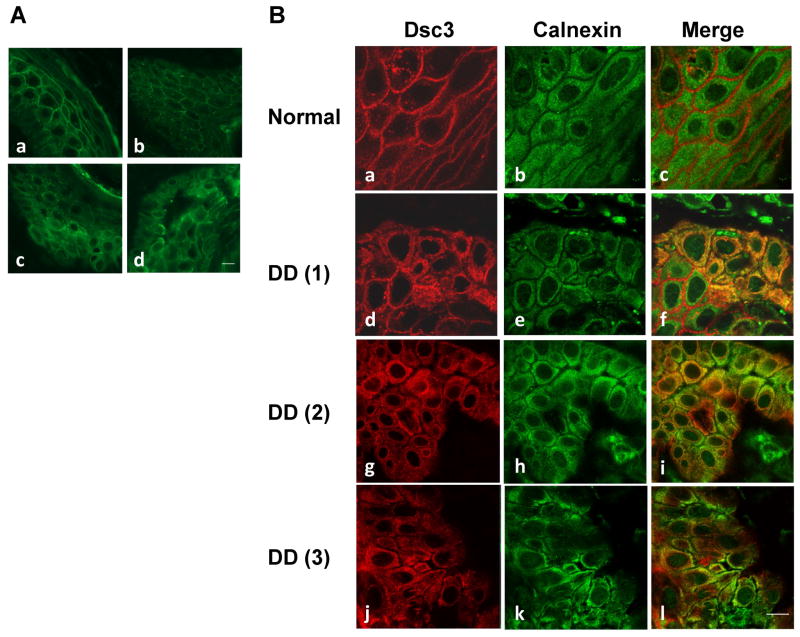

Dsc3 is retained in the ER in acantholytic areas of DD epidermis

To investigate whether ER retention of DC occurs in DD epidermis, we examined Dsc3 distributions on skin tissues obtained from DD patients (n=3) and a normal subject. In normal control epidermis, Dsc3 shows a more linear cell border staining (Fig. 6A, panel a), whereas in most regions of DD epidermis, Dsc3 displays a punctate distribution on cell border (Fig. 6A, panel b), which is likely due to the lack of supply of newly synthesized Dsc3 reaching the plasma membrane. In some regions of DD epidermis including acantholytic areas, perinuclear staining of Dsc3 is observed (Fig. 6A, panel c and d). Next, we analyzed the relative distributions of Dsc3 and calnexin by co-IF staining. The results show altered subcellular distribution of Dsc3 as well as calnexin in some regions of DD epidermis (Fig. 6B, DD vs normal), which are in line with TG-treated NHEK (Fig. 5). While the subcellular distribution pattern of Dsc3 is very similar to that of ER calnexin in DD epidermis (Fig. 6B, red vs green), colocalization of Dsc3 with calnexin (yellow/orange signals) is also revealed in some but not all keratinocytes. Our results of DD skin staining are consistent with those of DD keratinocyte culture studies in which colocalization of a fraction of DC with ER calnexin is observed 22.

Figure 6. ER retention of Dsc3 in DD epidermis.

(A) Skin tissues derived from a normal subject (a) and DD patients (b–d) were stained with Dsc3. (B) Skin tissues were dual labeled with Dsc3 (red) and ER calnexin (green) and examined in a confocal microscope. Colocalization of Dsc3 and calnexin (yellow signal) is revealed by merged images. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Discussion

Unlike DP, DC are secretory pathway glycoproteins that are synthesized on rough ER. Following translocation into the ER, DC undergo sequential post-translational modification in the ER and the Golgi apparatus before transport to the plasma membrane. Four stages have been identified along the trafficking pathway of DC in MDCK cells 26,31: i) in the ER, DC are synthesized as non-ionic detergent soluble precursors bearing a prodomain and are core-glycosylated (high-mannose carbohydrates that are Endo H-sensitive); ii) soluble DC precursors are transported to the Golgi apparatus, where N-linked carbohydrates are modified to the complex type (Endo H-resistance) and the prodomain is proteolytically cleaved; iii) soluble DC are titrated into an insoluble pool in the trans-Golgi complex; and iv) insoluble mature DC are transported to the plasma membrane.

Loss of SERCA activity may possibly affect various ER functions, such as folding, glycosylation, and export of secretory/membrane proteins, as well as Ca2+-dependent signaling. Our results show that inhibition of SERCA2 in keratinocytes neither affects core glycosylation nor induces any abnormal aggregates of nascent DC. Instead, transport of nascent DC from the ER to the Golgi is blocked. This is evidenced by: 1) the alterations of DC mobility; 2) the failure of titrating of DC into an insoluble pool; 3) the blockade of N-glycan processing from the high-mannose to the complex type; 4) the failure of cleavage of the prodomain; 5) the similar subcellular distribution pattern of DC with ER-resident calnexin; and 6) the partial colocalization of DC with calnexin.

How does SERCA2 inhibition block ER exit of nascent DC? Three observations suggest that ER retention of nascent DC in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes is a consequence of ER Ca2+ reduction below a threshold level. First, the effect of SERCA inhibitors on DC maturation is dose-dependent. While TG at 5 nM is ineffective on DC maturation, it becomes effective at higher doses. Second, partial loss of SERCA2 expression by siRNA silencing does not affect Dsc2/3 maturation; however, when combined with an ineffective dose of TG (5 nM), it blocks Dsc2/3 maturation. Third, the ineffective dose of TG becomes effective when RyRs is pharmacologically stimulated, which enhances the passive release of Ca2+ from the ER and thus further reduces ER Ca2+ content. Although we have not directly measured the ER Ca2+ concentration following TG treatment, a previous study by Celli et al. 41 has reported a dose-dependent effect of TG on ER Ca2+ reduction in NHEK that were cultured in the same conditions as ours. In that study, the normal level of ER Ca2+ in NHEK is around 180 μM and 10 nM TG treatment results in ER Ca2+ depletion to about 80 μM. Based on this report we speculate that the threshold level of ER Ca2+ for post-ER trafficking and processing of nascent DC in NHEK is about 80 μM, because at the dose of 10 nM TG, DC processing is partially affected as revealed by the presence of both the processed and unprocessed DC (data not shown). It is noteworthy to mention that glycosylation itself is not required for intracellular trafficking of DC, as tunicamycin treatment does not prevent unglycosylated Dsg transport to the plasma membrane 26. Moreover, prodomain cleavage is not required for Dsg trafficking, as recombinant Dsg3 ectodomain with a mutated cleavage site is still able to secrete into the culture medium 34.

A high concentration of Ca2+ in the ER is generally believed to be important for protein folding, as the function of molecules in the ER is Ca2+-dependent 42,43. However, it is known that not all secretory pathway proteins are affected by ER Ca2+ depletion 44. For example, in HepG2 hepatoma cells, TG treatment has no effect on secretion of albumin and transferrin but retards the plasma membrane transport of asialoglycoprotein receptor 45. Consistent with previous findings from other types of cells, our data show that TG treatment does not affect the maturation of TACE in NHEK, whereas the post-ER trafficking and processing of DC are blocked under the same condition. Our data support the notion that depletion of ER Ca2+ has no general inhibitory effect on folding and trafficking of proteins 45,46. Interestingly, among the secretory pathway proteins that have been reported to be affected by ER Ca2+ depletion in various types of cells, many are Ca2+-binding proteins. These include thyroglobulin in rat thyroid epithelial cells 47, asialoglycoprotein receptor in human hepatoma cells 45, low density lipoprotein receptor in Hela cells 48, Notch receptor in Drosophila 49, and E-cadherin in keratinocytes 21 (Li et al., unpublished data). It is probable that folding of Ca2+-binding proteins is more sensitive to ER Ca2+ reduction.

DC are Ca2+-binding and -dependent adhesion molecules 50. It is well established that Ca2+ is required for binding of pemphigus autoantibodies to Dsg1 and Dsg3 51 and for proteolytic cleavage of Dsg1 by exfoliative toxin 52. These findings indicate that incorporation of Ca2+ into the structures of DC is essential for maintaining a native conformation of these proteins. Thus, it is conceivable that without Ca2+ incorporation, newly synthesized DC, as well as other Ca2+binding secretory pathway proteins that are synthesized in keratinocytes, are misfolded in the ER. The misfolded proteins are unable to pass the ER quality control system, leading to their retention in the ER and eventually degradation by the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway 43,53. Consistent with this possibility, we often observe reduced steady-state levels of Dsc2/3 or Dsg3 in SERCA2-inhibited keratinocytes (e.g., Fig. 2). Additionally, the ER calnexin becomes more perinuclear localized both in TG-treated NHEK and in DD epidermis, indicating an ER stress response to ER Ca2+ reduction caused by SERCA2 inhibition.

It is well known that the ER stress response may lead to apoptosis if the early adaptive response failed 22,54,55. At higher doses (1–10 μM), TG induces apoptosis in various types of cells. However, under our conditions where TG (0.1 μM) affected the maturation of DC precursors, we did not detect increased expression of apoptotic markers (unpublished data). Moreover, treatment of keratinocytes with dithiothreitol, an ER stressor by a different mechanism, did not prevent DC maturation (unpublished data). These observations indicate that ER retention of nascent DC is caused by ER Ca2+ depletion rather than a general ER stress per se or ER stress-induced apoptosis.

The result that siRNA SERCA2 alone is not sufficient to impair the maturation of DC is informative. It is in line with the observations that DD epidermis exhibit focal but not generalized acantholysis, and that mislocalization of desmosomal components occurs only in the lesional but not perilesional or unaffected skin 10,13,56. It is plausible that keratinocytes with low levels of SERCA2 activity, together with upregulated compensatory proteins involving Ca2+ homeostasis in SERCA2-deficient cells 57–60, are able to maintain a content of ER Ca2+ above a threshold level for correct folding of nascent DC. A number of observations suggest that SERCA2 haploinsufficiency may not be sufficient for DD manifestation, and that other factors likely play an important role for disease development. i) Unlike most dominantly inherited skin disorders, the onset of DD is late rather than at birth. ii) Lesions are confined to certain areas of the skin rather than the entire body in most patients. iii) The severity of symptoms varies among patients, even among family members with the same mutations 61–63. iv) DD is exacerbated by heat, sweating, UV irradiation, friction, and infections. v) SERCA2+/− mice do not develop DD-like phenotype 60,64. Given these observations, it is plausible that keratinocytes with one functional copy of SERCA2 gene are capable of maintaining a suboptimal conditions for intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in most scenarios; however, when local Ca2+ homeostasis is perturbed further by other factors, disease is manifested. The wide spectrum of disease severity among DD patients is probably determined by variable extents of perturbation in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis.

Consistent with cell culture studies, perinuclear distribution of Dsc3 is observed in acantholytic regions of DD epidermis. The mislocalized Dsc3 shows a very similar staining pattern as the ER chaperone calnexin and many colocalize with calnexin, indicating ER retention in DD. Our finding that DC is partially colocalized with calnexin in DD epidermis complements the finding in DD keratinocyte culture 22, suggesting that ER retention of DC may contribute to DD pathogenesis. Current therapies for DD primarily rely on topical or oral retinoid; however, some patients are refractory to the treatment, and others cannot tolerate the treatment’s adverse effects 5,7. Based on our finding that ER Ca2+ is crucial for folding, trafficking, and maturation of nascent DC, potential new therapeutic strategies for DD may include use of agents that increase ER Ca2+ content and use of pharmacological chaperones that facilitate protein folding/trafficking.

Materials and Methods

Keratinocyte culture and treatment

Primary normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK), obtained from Cascade Biologics (Portland, OR), were cultured in EpiLife medium (0.06 mM calcium) supplemented with HKGS (Cascade Biologics). Cells at 3–5 passages were used for experiments. For SERCA inhibition, cells grown to confluence were treated with TG or CPA along with a high calcium (1.2 mM) switch for 6 hours or overnight (18 or 24 h). For controls, cells were treated with vehicle. TG and CPA were purchased from Sigma.

Protein extraction and Western blotting

For total protein extraction, cells were lysed in 2% SDS lysis buffer containing proteinase inhibitors. For protein solubility analysis, cells were extracted with 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer containing proteinase inhibitors. Insoluble pellet was solubilized in 2% SDS lysis buffer and analyzed as insoluble fraction. Protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein from each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto membranes, and probed with primary antibodies. Following incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, proteins were detected by chemiluminescence reaction using SuperSignal West (Pierce). The primary antibodies used were anti-Dsc2/3 (7G6, Invitrogen), anti-Dsg3 (5G11, Invitrogen), anti-SERCA2 (IID8, Millipore), anti-DP (Santa Cruz), anti-PG (clone 15, BD), and anti-TACE/ADAM17 (Millipore).

N-glycan removal and propeptide cleavage

N-glycans were removed by endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H (Endo H, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) or peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGase F, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Propeptide were cleaved by furin (New England BioLabs). For Endo H digestion, aliquots of total cell lysates from vehicle- or TG-treated cells were boiled for 5 min in 0.5% SDS and 40 μM DTT. After cool down to room temperature, denatured proteins were digested for 4 h at 37 °C with or without Endo H (20 units/μg protein) in buffer containing 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 5.5), 0.5 mM PMSF, and proteinase cocktail. For PNGase F digestion, aliquots of the same set of protein samples were boiled for 5 min in protein denaturing buffer (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, and 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and cooled down to room temperature. Denatured proteins were digested for 4 h at 37 °C with or without PNGase F (0.2 units/μg protein) in the presence of 0.75% Trion X-100. For furin digestion, aliquots of Triton X-100 soluble proteins from vehicle- or TG-treated cells were digested for 18 h at 30 °C with or without furin (0.04 units/μg protein) in buffer containing 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Following digestions, reactions were stopped by adding Laemmli buffer and subjected to Western Blot analysis.

SERCA2 knockdown

A pool of double-stranded siRNA oligonucleotide targeting human ATP2A2 gene and a non-targeting siRNA control were purchased from Dharmacon (SMARTpool, Thermo Scientific). NHEK were transfected with siRNA using TransMessenger Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) for 48 to 72 hours. The efficiency of SERCA2 knockdown was examined by WB using mouse monoclonal antibodies to SERCA2 (clone IID8, Millipore).

Immunocytochemistry

NHEK plated on glass coverslips were grown to subconfluence and treated as described above. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies to Dsg3 (5G11, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Dsc2/3 (7G6, Invitrogen), or rabbit polyclonal antibodies to calnexin (Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded skin specimens from patients with DD were obtained from the Department of Dermatology, Xi’An Jiaotong University, China. The diagnosis of DD was based on clinical and histological examination. Following deparaffinization, tissues sections were steamed with antigen retrieval buffer (BioGenex, Citra Plus, pH6.0) and stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies to Dsc3 (U114, GeneTex) and/or rabbit anti-calnexin. Anti-mouse or -rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa-Fluor-488 or Cy3 were used.

Synopsis.

Desmosomal cadherins (DC) are Ca2+-dependent transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes that are critical in maintaining keratinocyte cohesion. Darier’s disease (DD) is an autosomal dominant skin disease characterized by loss of desmosomes/cohesions between keratinocytes. The defective gene in DD is ATP2A2, which encodes SERCA2, a Ca2+-pump located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Here we show that SERCA2 is crucial for ER-to-Golgi transport of nascent DC. Colocalization of DC and ER calnexin is detected in DD epidermis, suggesting that ER retention of DC may contribute to DD pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH grants R01 AR061372 (NL), R01 AI040768 (ZL), and R01 AR032599 (LAD).

Abbreviations

- CMC

4-chloro-m-cresol

- CPA

cyclopiazonic acid

- DC

desmosomal cadherins

- DD

Darier disease

- Dsg

desmoglein

- DP

desmoplakin

- Dsc

desmocollin

- Endo H

Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HCM

high calcium media

- IF

immunofluorescence

- LCM

low calcium media

- NHEK

normal human epidermal keratinocytes

- PG

plakoglobin

- PNGase F

peptide-N-glycosidase F

- RyRs

ryanodine receptors

- SERCA

sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- TG

thapsigargin

- WB

Western blotting

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Thomason HA, Scothern A, McHarg S, Garrod DR. Desmosomes: adhesive strength and signalling in health and disease. Biochem J. 2010;429(3):419–433. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrof G, Mellerio JE, McGrath JA. Desmosomal genodermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(1):36–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubash AD, Green KJ. Desmosomes. Curr Biol. 2011;21(14):R529–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delva E, Tucker DK, Kowalczyk AP. The desmosome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(2):a002543. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulatt L, Burge S. Darier’s disease: hopes and challenges. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(9):439–441. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.9.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, Munro CS, Tavadia S, Craddock N. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2003;4(2):97–105. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savignac M, Edir A, Simon M, Hovnanian A. Darier disease: a disease model of impaired calcium homeostasis in the skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(5):1111–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caulfield JB, Wilgram GF. An Electron-Microscope Study of Dyskeratosis and Acantholysis in Darier’s Disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1963;41:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burge SM, Garrod DR. An immunohistological study of desmosomes in Darier’s disease and Hailey-Hailey disease. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124(3):242–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setoyama M, Hashimoto K, Tashiro M. Immunolocalization of desmoglein I (“band 3” polypeptide) on acantholytic cells in pemphigus vulgaris, Darier’s disease, and Hailey-Hailey’s disease. J Dermatol. 1991;18(9):500–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1991.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto K, Fujiwara K, Tada J, Harada M, Setoyama M, Eto H. Desmosomal dissolution in Grover’s disease, Hailey-Hailey’s disease and Darier’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22(6):488–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tada J, Hashimoto K. Ultrastructural localization of cell junctional components (desmoglein, plakoglobin, E-cadherin, and beta-catenin) in Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier’s disease, and pemphigus vulgaris. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25(2):106–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1998.tb01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;21(3):271–277. doi: 10.1038/6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavadia S, Authi KS, Hodgins MB, Munro CS. Expression of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase type 2 and 3 isoforms in normal skin and Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(2):440–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hovnanian A. SERCA pumps and human diseases. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:337–363. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart RO, Sun A, Bush KT, Nigam SK. Dependence of epithelial intercellular junction biogenesis on thapsigargin-sensitive intracellular calcium stores. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(23):13636–13641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leinonen PT, Myllyla RM, Hagg PM, et al. Keratinocytes cultured from patients with Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease display distinct patterns of calcium regulation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, Burge S, Hovnanian A. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(6):1349–1355. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobbs RP, Amargo EV, Somasundaram A, et al. The calcium ATPase SERCA2 regulates desmoplakin dynamics and intercellular adhesive strength through modulation of PKCα signaling. FASEB J. 2011;25(3):990–1001. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-163261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Celli A, Mackenzie DS, Zhai Y, et al. SERCA2-controlled Ca(2)+-dependent keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation is mediated via the sphingolipid pathway: a therapeutic target for Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(4):1188–1195. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savignac M, Simon M, Edir A, Guibbal L, Hovnanian A. SERCA2 dysfunction in Darier disease causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and impaired cell-to-cell adhesion strength: rescue by Miglustat. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(7):1961–1970. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watt FM, Mattey DL, Garrod DR. Calcium-induced reorganization of desmosomal components in cultured human keratinocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99(6):2211–2215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattey DL, Burdge G, Garrod DR. Development of desmosomal adhesion between MDCK cells following calcium switching. J Cell Sci. 1990;97( Pt 4):689–704. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penn EJ, Burdett ID, Hobson C, Magee AI, Rees DA. Structure and assembly of desmosome junctions: biosynthesis and turnover of the major desmosome components of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells in low calcium medium. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(5):2327–2334. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasdar M, Nelson WJ. Regulation of desmosome assembly in epithelial cells: kinetics of synthesis, transport, and stabilization of desmoglein I, a major protein of the membrane core domain. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(1):163–177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treiman M, Caspersen C, Christensen SB. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19(4):131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidler NW, Jona I, Vegh M, Martonosi A. Cyclopiazonic acid is a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(30):17816–17823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrmann-Frank A, Richter M, Lehmann-Horn F. 4-Chloro-m-cresol: a specific tool to distinguish between malignant hyperthermia-susceptible and normal muscle. Biochemical pharmacology. 1996;52(1):149–155. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Petegem F. Ryanodine receptors: structure and function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287(38):31624–31632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.349068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penn EJ, Hobson C, Rees DA, Magee AI. Structure and assembly of desmosome junctions: biosynthesis, processing, and transport of the major protein and glycoprotein components in cultured epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(1):57–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parrish EP, Marston JE, Mattey DL, Measures HR, Venning R, Garrod DR. Size heterogeneity, phosphorylation and transmembrane organisation of desmosomal glycoproteins 2 and 3 (desmocollins) in MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 1990;96( Pt 2):239–248. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penn EJ, Hobson C, Rees DA, Magee AI. The assembly of the major desmosome glycoproteins of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. FEBS Lett. 1989;247(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amagai M, Ishii K, Takayanagi A, Nishikawa T, Shimizu N. Transport to endoplasmic reticulum by signal peptide, but not proteolytic processing, is required for formation of conformational epitopes of pemphigus vulgaris antigen (Dsg3) J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(4):539–542. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12582796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Posthaus H, Dubois CM, Muller E. Novel insights into cadherin processing by subtilisin-like convertases. FEBS Lett. 2003;536(1–3):203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03897-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokouchi M, Saleh MA, Kuroda K, et al. Pathogenic epitopes of autoantibodies in pemphigus reside in the amino-terminal adhesive region of desmogleins which are unmasked by proteolytic processing of prosequence. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(9):2156–2166. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma PM, Choi EJ, Kuroda K, Hachiya T, Ishii K, Payne AS. Pathogenic anti-desmoglein MAbs show variable ELISA activity because of preferential binding of mature versus proprotein isoforms of desmoglein 3. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(9):2309–2312. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidah NG. What lies ahead for the proprotein convertases? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1220:149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franzke CW, Cobzaru C, Triantafyllopoulou A, et al. Epidermal ADAM17 maintains the skin barrier by regulating EGFR ligand-dependent terminal keratinocyte differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209(6):1105–1119. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlondorff J, Becherer JD, Blobel CP. Intracellular maturation and localization of the tumour necrosis factor alpha convertase (TACE) Biochem J. 2000;347(Pt 1):131–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Celli A, Mackenzie DS, Crumrine DS, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion activates XBP1 and controls terminal differentiation in keratinocytes and epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(1):16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashby MC, Tepikin AV. ER calcium and the functions of intracellular organelles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(1):11–17. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braakman I, Bulleid NJ. Protein folding and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:71–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062209-093836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevens FJ, Argon Y. Protein folding in the ER. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10(5):443–454. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lodish HF, Kong N, Wikstrom L. Calcium is required for folding of newly made subunits of the asialoglycoprotein receptor within the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(18):12753–12760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wikstrom L, Lodish HF. Unfolded H2b asialoglycoprotein receptor subunit polypeptides are selectively degraded within the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(19):14412–14416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Jeso B, Pereira R, Consiglio E, Formisano S, Satrustegui J, Sandoval IV. Demonstration of a Ca2+ requirement for thyroglobulin dimerization and export to the golgi complex. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252(3):583–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pena F, Jansens A, van Zadelhoff G, Braakman I. Calcium as a crucial cofactor for low density lipoprotein receptor folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(12):8656–8664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Periz G, Fortini ME. Ca(2+)-ATPase function is required for intracellular trafficking of the Notch receptor in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1999;18(21):5983–5993. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Syed SE, Trinnaman B, Martin S, Major S, Hutchinson J, Magee AI. Molecular interactions between desmosomal cadherins. Biochem J. 2002;362(Pt 2):317–327. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amagai M, Ishii K, Hashimoto T, Gamou S, Shimizu N, Nishikawa T. Conformational epitopes of pemphigus antigens (Dsg1 and Dsg3) are calcium dependent and glycosylation independent. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105(2):243–247. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12317587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanakawa Y, Selwood T, Woo D, Lin C, Schechter NM, Stanley JR. Calcium-dependent conformation of desmoglein 1 is required for its cleavage by exfoliative toxin. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(2):383–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brodsky JL, Skach WR. Protein folding and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: Recent lessons from yeast and mammalian cell systems. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(4):464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mekahli D, Bultynck G, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Missiaen L. Endoplasmic-reticulum calcium depletion and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(6) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onozuka T, Sawamura D, Goto M, Yokota K, Shimizu H. Possible role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of Darier’s disease. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41(3):217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leinonen PT, Hagg PM, Peltonen S, et al. Reevaluation of the normal epidermal calcium gradient, and analysis of calcium levels and ATP receptors in Hailey-Hailey and Darier epidermis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009;129(6):1379–1387. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pani B, Cornatzer E, Cornatzer W, et al. Up-regulation of transient receptor potential canonical 1 (TRPC1) following sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2 gene silencing promotes cell survival: a potential role for TRPC1 in Darier’s disease. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(10):4446–4458. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foggia L, Aronchik I, Aberg K, Brown B, Hovnanian A, Mauro TM. Activity of the hSPCA1 Golgi Ca2+ pump is essential for Ca2+-mediated Ca2+ response and cell viability in Darier disease. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 4):671–679. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seth M, Sumbilla C, Mullen SP, et al. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) gene silencing and remodeling of the Ca2+ signaling mechanism in cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(47):16683–16688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407537101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao XS, Shin DM, Liu LH, Shull GE, Muallem S. Plasticity and adaptation of Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in SERCA2(+/−) mice. The EMBO journal. 2001;20(11):2680–2689. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ringpfeil F, Raus A, DiGiovanna JJ, et al. Darier disease--novel mutations in ATP2A2 and genotype-phenotype correlation. Experimental dermatology. 2001;10(1):19–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Onozuka T, Sawamura D, Yokota K, Shimizu H. Mutational analysis of the ATP2A2 gene in two Darier disease families with intrafamilial variability. The British journal of dermatology. 2004;150(4):652–657. doi: 10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huo J, Liu Y, Ma J, Xiao S. A novel splice-site mutation of ATP2A2 gene in a Chinese family with Darier disease. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(10):769–772. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu LH, Boivin GP, Prasad V, Periasamy M, Shull GE. Squamous cell tumors in mice heterozygous for a null allele of Atp2a2, encoding the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 Ca2+ pump. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276(29):26737–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]