SUMMARY

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) is a common inflammatory disorder that strongly impacts patients' quality of life. CRSwNP is still a challenge for ENT specialists due to its unknown pathogenesis, difficult control and frequent relapse. We tested the hypothesis that a new standardised therapeutic approach based on individual clinical-cytological grading (CCG), may improve control of the disease and prevent the needing for surgery. We analysed 204 patients suffering from bilateral CRSwNP, 145 patients of whom regularly assumed therapy, respecting the planned check-up, and were considered cases; 59 patients were not assuming therapy as indicated and were considered as controls. After five years of standardised treatment, 15 of 145 (10.5%) improved endoscopic staging, 61 of 145 (42%) did not change their endoscopic staging, and 69 of 145 (47.5%) were worse. In the control group, 49 of 59 (83%) were worse by at least two stages (p < 0.05). Patients and controls were stratified basing on clinical and cytological grading as mild, moderate and severe. After patient stratification, in the mild group (n = 27) 92% patients had a constant trend, with no worsening and no need for surgery over a 5-year period, whereas in the mild CCG control group 1 of 59 (1.6%) required surgery (p < 0.05). In moderate GCC (n = 83), 44% of patients did not modify or improve endoscopic staging and 3.6% needed surgery, compared to 13.6% of controls with moderate GCC (p < 0.05). In severe CCG (n = 35), even though no patients achieved significant amelioration of endoscopic grading, 40% of patients were considered as "clinically controlled" and 5.7% of patients underwent surgery, but the percentage was significantly higher (49%) in the control group significant (p = 0.0000). Finally, statistical analyses revealed a clear trend that polyp size increased at a faster rate in the control group than in the treatment group and for each subgroup (low, moderate and severe). The present study suggests a new approach in the management of CRS according to clinical cytological grading that allows defining the grade of CRSwNP severity and to adapt the intensity of treatment. This approach limited the use of systemic corticosteroids to only moderate-severe CRSwNP with a low corticosteroid dosage in comparison with those previously suggested. Our protocol seems to improve the adherence by patients, control of disease and the need for surgery in the long-term.

KEY WORDS: Nasal polyps, Clinical grading, Cytological grading, Treatment

RIASSUNTO

La rinosinusite cronica con polipi nasali (CRSwNP) è una malattia cronica nasosinusale, a eziologia infiammatoria, con significativo impatto negativo sulla qualità di vita dei pazienti. La CRSwNP rappresenta ancora oggi una sfida terapeutica per lo specialista ORL, sia per la comprensione della sua eziopatogenesi, sia per il suo controllo clinico ed è questo è testimoniato dalla alta incidenza di recidiva dopo trattamento. Abbiamo voluto verificare l'ipotesi che un approccio terapeutico nuovo, standardizzato, e individualizzato sul grading clinico-citologico (clinical-cytological grading – CCG) consentisse un miglior controllo dei sintomi della malattia, e di ridurre la necessità di ricorrere alla chirurgia. Abbiamo pertanto reclutato 204 pazienti affetti da CRSwNP, di cui 145 hanno regolarmente assunto la terapia rispettando il protocollo proposto, e 59 pazienti, invece, che non hanno assunto la terapia in modo sistematico e sono stati quindi inclusi come controlli. Dopo 5 anni di trattamento standardizzato, abbiamo notato che 15 pazienti su 145 (10,3%) del gruppo con terapia standardizzata avevano avuto un miglioramento dello staging endoscopico, 61 su 145 (42%) si erano mantenuti costanti, mentre 69/145 (47,5%) erano andati incontro a un peggioramento. Nel gruppo di controllo, invece, i pazienti peggiorati erano ben 49 su 59 (83%), con un peggioramento significativo in termini di grading endoscopico di almeno due classi (p < 0,05). I pazienti e i controlli sono stati successivamente stratificati sulla base del CCG in 3 sottogruppi: pazienti con CCG lieve, moderata e grave. Dopo tale suddivisione in classi, è stato possibile evidenziare che nel gruppo con CCG lieve (n = 27), il 92% dei pazienti manteneva negli anni un trend costante, in assenza di peggioramenti e senza necessità di ricorrere alla chirurgia nei 5 anni di osservazione, mentre nel gruppo di controllo, 1 paziente su 59 (1,6%; p = <0,05) ricorreva a chirurgia. Nel gruppo con CCG moderato (n = 83), invece, il 44% dei pazienti "standardizzati" non aveva avuto un peggioramento di grading endoscopico, con un 3,6% di pazienti che aveva avuto necessità di ricorrere alla chirurgia, contro il 13,6% del gruppo controllo (p < 0,05). Nel gruppo dei pazienti con CCG grave (n = 35), anche se nessun paziente riusciva a ottenere un miglioramento del grading endoscopico, il 40% dei pazienti veniva comunque giudicato "controllato" da un punto di vista clinico. Nel gruppo dei pazienti con CCG grave, ben il 5,7% dei pazienti necessitava di trattamento chirurgico, ma anche in questo caso, la percentuale dei pazienti operati era significativamente maggiore (p = 0,0000) nel gruppo di controllo (49%). Infine, l'analisi statistica effettuata ha dimostrato chiaramente che, da un punto di vista obiettivo, le dimensioni dei polipi nasali tendevano ad aumentare a una velocità maggiore nel gruppo controllo che nel gruppo "standardizzato", con incrementi proporzionali nelle tre classi di CCG (lieve, moderato e grave). Lo studio attuale fornisce le basi per lo sviluppo e l'adozione di un nuovo approccio per la gestione della CRSwNP sulla base di uno score clinico e citologico (CCG) che permetta di stimare con accuratezza la gravità della CRSwNP e di adattarne il trattamento. Tale approccio limita l'uso degli steroidi sistemici alle sole classi CCG di entità moderata-grave con dosi di steroidi inferiori rispetto a quanto precedentemente suggerito in letteratura. Il nostro protocollo può migliorare pertanto l'aderenza terapeutica dei pazienti, il tasso di controllo della malattia e può ridurre il ricorso alla chirurgia nel corso degli anni.

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) is a common inflammatory disorder, affecting about 4% of the population worldwide and strongly impacts the quality of life of affected patients 1. CRSwNP remains a challenge for ENT specialists because of its unknown pathogenesis, difficult control and frequent relapse.

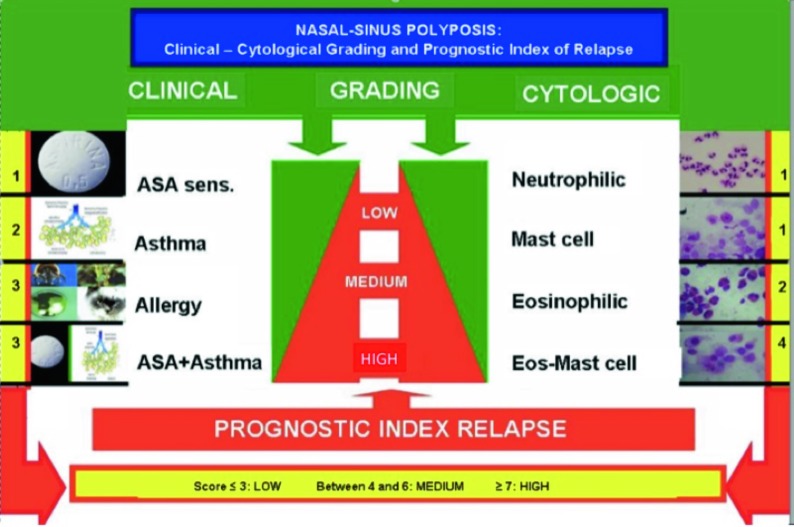

CRSwNP is characterised by different phenotypes depending on: comorbidity 2, endoscopic findings 3, radiological features 4 and cytology 5. In this regard, a clinicalcytological grading (CCG) has been proposed for defining a prognostic index of relapse, as reported in Figure 1 6.

Fig. 1.

Prognostic index of nasal polyp relapse based on clinical and cytologic grading.

Management of CRSwNP consists of a combination of medical therapy, careful follow-up, and appropriate surgery; this strategy should be individualised for each single patient. Corticosteroids (CS), both topical and systemic, and functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) are the most common approaches 7 8. Even though medical treatment usually allows satisfactory control in most patients 9, some subjects need surgery 10. Nevertheless, some patients, ranging between 15 to 87% of those undergoing surgery, may have relapse 11. Therefore, there is the need for a therapeutic algorithm based on CRSwNP phenotyping. An appropriate strategy is mandatory to avoid under/ overtreatment, prevent relapse and minimise the side effects of medication.

The present study examined the hypothesis that a new standardised therapeutic approach to CRSwNP based on clinical and cytological grading may improve control of disease and potentially prevent surgery and relapse.

Materials and methods

Two hundred four patients (117 males, 87 females, mean age 41 years, age range 28-71) suffering from bilateral CRSwNP were evaluated. CRSwNP diagnosis was performed by history (including ASA sensitivity), nasal endoscopy, cytology and allergy testing.

Nasal cytology was performed by scraping the middle part of the inferior turbinate with a Rhino-Probe® device (Arlington Scientific), according to validated criteria 12. The inflammatory pattern of inflammation was in 91 of 204 (44.6%) patients with eosinophils; in 37 of 204 (18.1%) with mast cells; in 73 of 204 (35.7%) with mixed mast cells and eosinophils; finally, in only 3 of 204 (1.4%) patients with neutrophils. We never observed modification of inflammatory patterns over the years.

Skin prick test was performed according to validated criteria 13. Allergy was detected in 93 of 204 (45%) patients, 71 of 204 (34.8%) were poly-sensitised, 32 of 204 (15.7%) patients were asthmatic; 23 of 204 (11.3%) patients had aspirin (ASA) intolerance and 59 of 204 (28.9%) had ASA sensitivity associated with asthma.

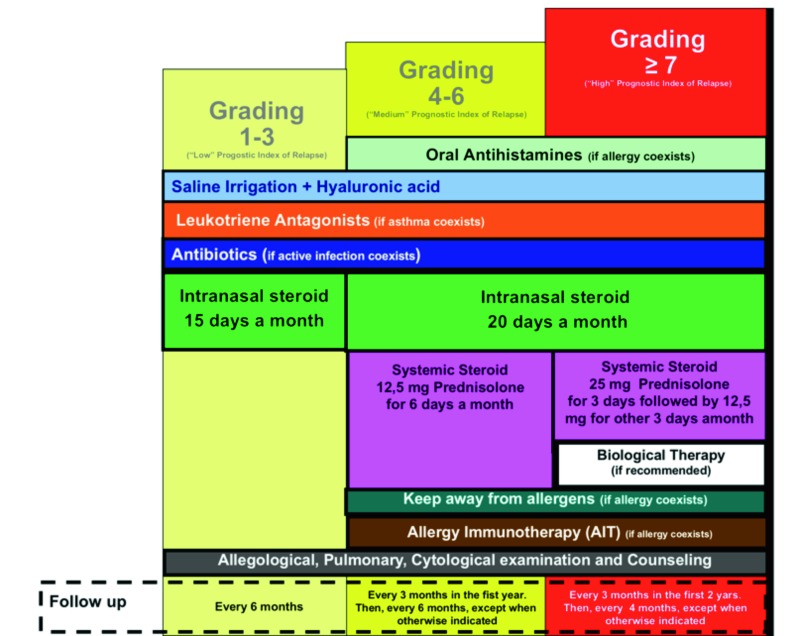

Clinical and cytologic grading and prognostic index of nasal polyps relapse are reported in Figure 1. Our diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for nasal polyposis.

The standardised therapeutic approach based on clinical and cytological grading (CCG) was followed by 145 of 204 patients who regularly assumed therapy and respected the planned check-up and were considered cases; 59 of 204 patients were not assuming the therapy as indicated and assumed only topical corticosteroids, and for this reason where considered as a control group.

CCG-treated patients and controls were stratified basing on clinical and cytological grading (15). Patients and controls were subdivided in three groups on the basis of CCG: group A: mild grade (CCG 1-3); group B: moderate (CCG 4-6); and group C: severe (CCG 7-10). Among cases, 27 of 145 (18%) were considered mild CCG; 83/ of 145 (57%) moderate CCG and 35 of 145 (24%) severe CCG. In the controls, 15 of 59 (25%) had mild CCG, 32/ of 59 (54%) had moderate and 12 of 59 (20%) had severe CCG.

The medical treatment prescribed based on clinical and cytological grading (CCG) is reported in Figure 3. Nasal irrigation using isotonic saline, at low pressure and large volume 14, was used by all patients. In low grade patients, furoate mometasone (200 mcg/day) was prescribed for 15 days a month, and montelukast 10 mg/day if asthma occurred. In patients with moderate grade, antihistamines and allergen immunotherapy (if indicated) were added; mometasone was prescribed for 20 days per month; and oral corticosteroid was added: prednisone 12.5 mg/day for 6 days per month. In patients with severe grade, 25 mg prednisone was prescribed per 3 days, then 12.5 mg for 3 days per month. Controls assumed only local corticosteroid furoate mometasone (200 mcg/day) which was prescribed for 15 days a month.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of nasal polyp treatment on the basis of proposed grading.

Nasal endoscopy was carried out by a 3.4 mm diameter flexible fiberscope (Vision-Sciences® ENT-2000). NP endoscopic classification proposed by Meltzer3 was adopted (stage 0: no polyps visualised and open middle meatus; stage 1: small polyps noted in the middle meatus; Stage 2: middle meatus completely filled with polypoid disease; Stage 3: polyps extending out of the middle meatus but the above inferior turbinate; Stage 4: massive nasal polyposis filling the entire nasal cavity and spheno-ethmoid region).

The patients were followed for 5 years. Patient outcomes were evaluated at baseline (T0), after 1 year (T1), and after 5 years (T2). The Review Board of the Policlinico of Bari approved the procedure and all patients provided informed written consent.

Statistical analysis

Data came from an ordinal longitudinal clinical trial. The statistical analysis was mainly aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a calibrated therapeutic protocol, based on the CCG versus topical corticosteroid therapy. The population sample was subdivided in three subgroups according to CCG score (A, B and C).

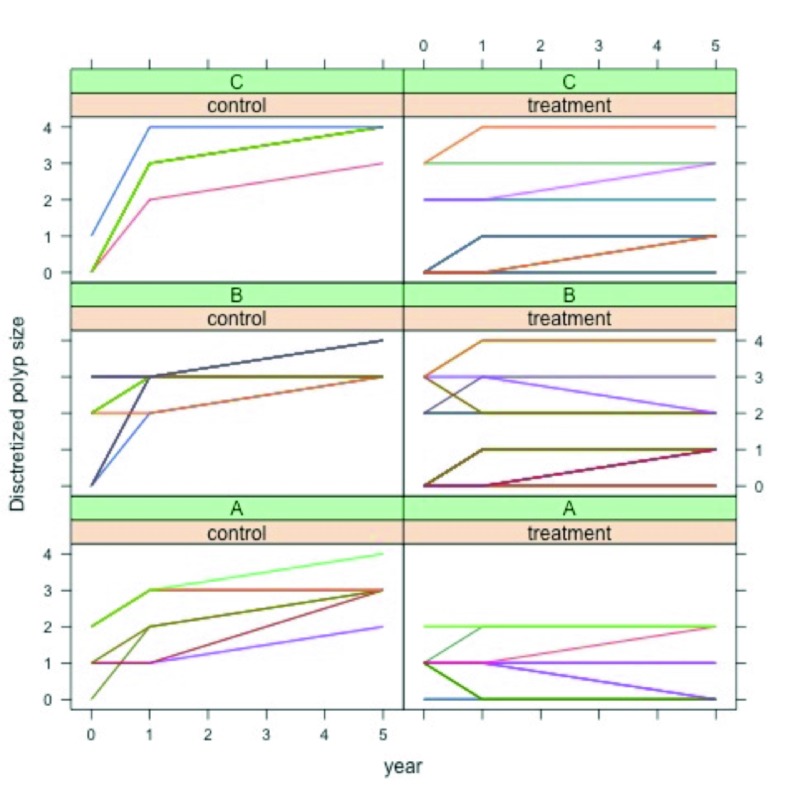

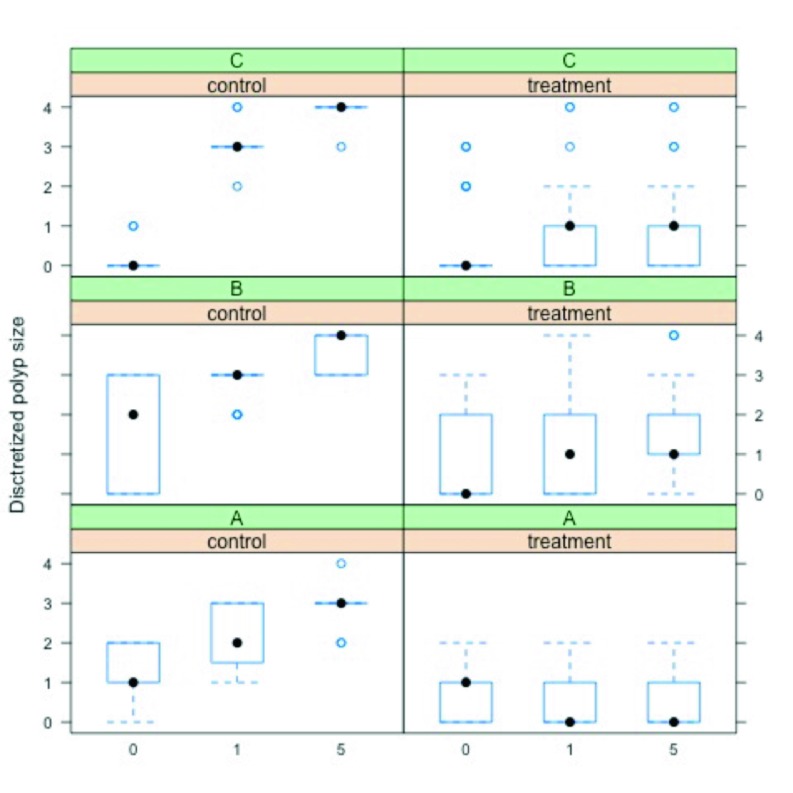

As a preliminary explorative data analysis, the discretised polyp size responses Υit were plotted as a function of time τ conditioned on the treatment tr and on subsample A, B and C. A further summarised presentation of trend was generated in a conditioned boxplot.

The cumulative logit marginal model described in ([1], [3]) was fitted to data for each subsample A, B and C. The repeated response variable Υit was the discretised polyp size of each subject ι in the study , classified on a five-level ordinal scale with possible values y = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 (0 = low;4 = high), at time t = 0 (baseline classification) and at two follow-up times: one year (t = 1) and five years (t = 5).

Data were acquired and analysed using R 3.0.1 software (R Core Team 2015 https://www.R-project.org).

Results

After one year of standardised treatment (T1), 10 cases of 145 (6.8%) improved endoscopic staging by at least one stage, 75 of 145 (51.7%) did not change their stage and 50 of 145 (34.48%) were worse at endoscopic staging of no more than one stage. In the control group, 22 of 59 (37.2%) did not change their staging, whereas 37 of 59 (62.7%) were worse by at least one-two stages.

After five years of standardised treatment (T2), 15 of 145 (10.3%) improved endoscopic staging, 61 of 145 (42%) did not change endoscopic staging and 69 and 145 (47.5%) were worse. In the control group, 49 of 59 (83%) were worse by at least two stages.

The outcomes after treatment according to clinical cytological staging are reported in Table 1. In group A (mild CCG), 92% of patients did not modify or improve endoscopic staging; no patients in this group required surgery; in mild GCC of the control group 1 of 59 (1.6%) required surgery (p < 0.05). In group B (moderate CCG), 44% of patients did not modify or improve endoscopic staging and 3 of 83 patients (3.6%) required functional endoscopic sinus surgery versus 8/59 (13.55%) in controls (p < 0.05). In group C (severe GCC), no patients improved endoscopic staging, 40% of patients did not worsen; 2 of 35 patients (5.7%) required surgery versus 20 of 59 (33.8%) in the control group. During the five-year follow-up, 5 of 145 treated patients (3.4%) underwent functional endoscopic sinus surgery, and in particular 3 with moderate CCG and 2 with severe CCG; in the control group, 29 of 59 (49%) underwent surgery (p = 0.0000).

Table I.

5-year follow-up after treatment by endoscopic staging, stratifying results according to the clinical cytological grading.

| Improved | Not modified | Worsening | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| GCC 1-3 | 9/27 (33.3%) |

0/15 (0%) |

16/27 (59.2%) | 2/15 (13.3%) |

2/27 (7.4%) |

13/15 (86.6%) |

| GCC 4-6 | 6/83 (7.2%) |

0/32 (0%) |

31/83 (37.34%) | 8/32 (25%) |

46/83 (55%) |

24/32 (75%) |

| GCC ≥7 | 0/35 (0%) |

0/12 (0%) |

14/35 (40%) | 0/12 (0%) |

21/35 (60%) |

12/12 (100%) |

| Totale | 15/145* (10.3%) |

0 (0%) |

61/145* (42%) |

10/59 (16.9%) |

69/145* (47.5%) |

49/59 (83%) |

p < 0.05

Figure 4 shows a plot of the discretised polyp size response Υit, for each subject ι, as a function of time τ, conditioned on group (control, treatment) and on subsample (A,B,C). From the plot a clear trend is revealed; i.e., on average polyp size increased at a faster rate in the control group than in the treatment group, for each subsample. Figure 5 shows a summary of the same trend with boxplots.

Fig. 4.

Plot of the discretised polyp size for each subject, as a function of time, conditioned on group and subsample.

Fig. 5.

Boxplot of the discretised polyp size for each subject, as a function of time, conditioned on group and subsample.

The GEE estimates of the relevant parameters βtr and βtt/tr, the related estimated standard errors based on the sandwich covariance matrix, Wald's z-statistics and p-values, for each subsample A, B and C, are reported in Table II.

Table II.

Parameter estimates, standard errors, z-statistics and p-values for each subsample.

| Parameter | Estimate | Std. Error | z-statistic | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | βtr | 3.910 | 0.814 | 4.803 | < 0.001 |

| βt/tr | 3.024 | 0.741 | 4.079 | < 0.001 | |

| B | βtr | 4.574 | 0.787 | 5.810 | < 0.001 |

| βt/tr | 2.184 | 0.545 | 4.009 | < 0.001 | |

| C | βtr | 3.511 | 0.875 | 4.012 | < 0.001 |

| βt/tr | 2.077 | 0.598 | 3.474 | < 0.001 |

In each subgroup, the effect of calibrated treatment at time t = 1 year was positive and statically significant at a= 0:05 (H0: βtr = 0 rejected) as well as the interaction effect (H0: βtt/tr = 0 rejected).

For subsample A, the estimated cumulative odds of subjects in the treatment group was 49.88 (t = 1 year) and 1026.38 (t = 5 years) times those of subjects in the control group. For subsample B, the estimated cumulative odds of subjects in the treatment group was 96.97 (t = 1 year) and 861.61 (t = 5 years) times those of subjects in the control group. For sub sample C, the estimated cumulative odds of subjects in the treatment group was 45.20 (t = 1 year) and 267.24 (t = 5 years) times those of subjects in the control group.

Discussion

Many studies 15-21 have conducted on CRSwNP to attempt to clarify the aetiology of the disease, and even though several hypothesis have been postulated, none has been universally accepted by the international scientific community. Furthermore, despite improvements in medical and surgical therapy for NP, no significant efforts have been made in phenotyping the disease.

From a cytological point of view, recent studies have shown that CRSwNP is highly associated with an immune- inflammatory state, characterised by eosinophils and mast cells, sometimes associated, albeit more rarely, with neutrophils 22. From a clinical point of view, it is well known that CRSwNP is commonly associated with other comorbidities (allergy, asthma, ASA-intolerance) that are able to influence the course of NP 23 24.

All these factors confirm the clinical impression that different phenotypes exist and that treatment modalities should be tailored to them. Recent evidence suggests the possibility of "precision medicine" 25, based on the specific phenotype of each patient, allowing tailored treatment, minimising collateral effects and reducing the risks of under/overtreatment. Moreover, in a chronic disease scenario, it is mandatory to have the most precise diagnosis possible: this may help to develop more accurate therapy, with more satisfactory results and more long-term adherence to treatment.

This is the first innovative longitudinal study based on "personalised" medical treatment accordingly to clinical cytological grading (CCG) and therefore tailored to each patient.

In our model, every patient with CRSwNP has a unique identity, based not only on clinical features, such as the size of the polyp and comorbidities, but also by the cellular infiltrate. The combination of all these elements determines the clinical course of CRSwNP. Therefore, the different groups were subdivided on the basis of CCG, a stratification system for CRSwNP that we first developed and applied in our clinical practice in 2009 6, in order to associate different phenotypes to different treatment modalities.

Our approach has given us the advantage of treating patients with low CCG with exclusive topical steroids, whereas patients with higher CCG (> 4) were treated with systemic steroids, but with doses and treatment duration that are significantly lower in comparison to that reported in the literature.

In fact, no more than 75 mg and 112.5 mg of prednisone per month (in one week of therapy) were administered to the moderate and severe CCG groups, respectively, which is a much lower dose compared to that suggested by Hissaria 26 (50 mg per day for 2 weeks, with a total dose of 700 mg prednisone per month), Vaidayanathan 27 (25 mg per day for 2 weeks, with a total dose of 350 mg prednisone per month), and Alobid 28 (prednisone 170 mg in one week). We believe that a rational and weighted use of systemic steroids is one of the key elements to obtain high adherence to treatment by patients, especially in those at risk for steroid-associated comorbidities (e.g.: diabetes, hypertension, glaucoma, gastritis). Compliance to therapy and basic information on the disease features, coupled with instructions on the use of nasal steroids, were, in our opinion, one of the possible reasons for the low percentage of surgical procedures in our patients with CRSwNP. Moreover, our study demonstrated that a personalised use of steroids, with our posology and time intervals, was able to control CRSwNP much better in CCG groups than in the control group (p = 0.0000). Steroids, both topical and systemic, are the main agents responsible for reducing the inflammatory infiltrate, especially when eosinophils and mast cells are present in association. It has been demonstrated that the presence of both mast cells and eosinophils is the main factor responsible for high CCG 6.

In the group with mild CCG, 92% of patients had a constant trend, with no worsening and no need for surgery over a 5-year period, whereas in mild CCG of the control group 1 of 59 patients (1.6%) required surgery (p < 0.05). In the group with moderate CCG (n = 83), 44% of patients did not modify or improve endoscopic staging and 3.6% needed surgery, versus 13.55% of controls with moderate CCG (p < 0.05). In the group with severe CCG, even though no patients achieved significant amelioration of endoscopic grading, 40% of patients were considered as "clinically controlled", namely with sufficient respiratory function, absence of complications and a good quality of life. In patients with severe CCG, 5.7% of patients underwent surgery that was performed in case of obstructive CRSwNP, in presence of complications or a low quality of life, but this percentage was significantly higher (49%) in the control group and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0000). Finally, statistical analyses revealed a clear trend that polyp size increased at a faster rate in the control group than in the treatment group, for each subgroup (low, moderate and severe).

In a very recent study by Oscarsson et al. 29, patients with untreated CRSwNP were observed for 13 years with no specific therapeutic intervention: interestingly, they showed that CRSwNP is a chronic entity, with a variable course over the years, that does not necessarily evolve into a more serious condition. Even though not specifically indicated by the authors, it is clear that there is a clinical CRSwNP phenotype, with a lower "grading" and a more benign course.

One of the most challenging aspects of CRSwNP is their relapse after surgery, which is still a common event despite continuous refinements of surgical techniques and therapy modalities. Hopkins and colleagues 30 described a 4% revision rate at 12 months post-operatively, which increased to 11% at 36-month follow-up. Masterson et al. 31 reported a revision rate of 12.3%, while in 2012 EPOS (12) depicted a highly variable percentage of recurrence, varying from 4% to 60%, with a mean of 20%. In our opinion, this elevated heterogeneity in CRSwNP recurrence reflects the variability of CCG grading in patients, which could be only hypothesised in the prior studies, but which could be demonstrated in larger groups of patients. Our low percentage of "surgical" patients demonstrates that our tailored approach is successful and that this is the consequence of adequate phenotyping of CRSwNP. In addition, we believe that proper counseling, tailored information and useful advice to manage CRSwNP symptoms are the basic elements for efficacious management of such a complex disease. On the other hand, emerging data 32 33 are now available from studies about the possibility of targeting therapy to different endotype of CRS with NP, focusing on prominent cytokines, which are key features of eosinophilic CRSwNP. With the availability of various hmAbs to specifically target cytokines and their receptors, we cannot exclude a refinement of our approach integrating indication, and in particular to control severe disease.

Conclusions

Nowadays, personalised medicine represents a new frontier in medical progress. Several respiratory and headneck disorders have been explored, but CRSwNP remains a unclear area. In this regard, CRSwNP phenotyping is a fruitful attempt to tailor the best treatment and to avoid under or overtreatment. The present experience is the first longitudinal study aimed to calibrate medical treatment according to CCG. Each phenotype represents a fingerprint of pathophysiological mechanisms involved in CRSwNP, specific for each patient. CCG allows to define the grade of CRSwNP severity and to adapt the intensity of treatment. This approach limits the use of systemic corticosteroids to only moderate-severe CRSwNP. In addition, the proposed schedules consist of low CS dosage in comparison with those previously reported. Our protocol seems to improve adherence by patients, frequently suffering from co-morbidities, the rate of control disease and need forsurgery in the long-term.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, et al. EPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologists. Rhinology. 2012;50:1–12. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachert C, Zhang N, Holtappels G, et al. Presence of IL-5 protein and IgE antibodies to staphylococcal enterotoxins in nasal polyps is associated with comorbid asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:962–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: developing guidance for clinical trials. Rhinosinusitis Initiative. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(5 Suppl):S17–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelardi M, Russo C, Fiorella ML, et al. Inflammatory cell types in nasal polyps. Cytopathology. 2010;2:201–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelardi M, Fiorella R, Fiorella ML, et al. Nasal-sinus polyposis: clinical-cytological grading and prognostic index of relapse. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2009;23:181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalish L, Snidvongs K, Sivasubramaniam R, et al. WITHDRAWN: topical steroids for nasal polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Apr 25;4:CD006549–CD006549. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006549.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stammberger H. Surgical treatment of nasal polyps: past, present, and future. Allergy. 1999;53:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1999.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deloire C, Brugel-Ribère L, Peynègre R, et al. Microdebrider polypectomy and local corticosteroids. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2007;124:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.aorl.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonfils P. Evaluation of the combined medical and surgical treatment in nasal polyposis. I: functional results. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:436–446. doi: 10.1080/00016480600895078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelardi M, Iannuzzi L, Quaranta N, et al. Nasal cytology: practical aspects and clinical relevance. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:785–792. doi: 10.1111/cea.12730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet J, Heinzerling L, Bachert C, et al. Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, author, author. Practical guide to skin prick tests in allergy to aeroallergens. Allergy. 2012;67:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlandi RR, Smith TL, Marple BF, et al. Update on evidencebased reviews with recommendations in adult chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(Suppl 1):S1–S15. doi: 10.1002/alr.21344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam K, Schleimer R, Kern RC. The etiology and pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis: a review of current hypotheses. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:41–41. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0540-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corso E, Baroni S, Lucidi D, et al. Nasal lavage levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and chronic nasal hypereosinophilia. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:557–562. doi: 10.1002/alr.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corso E, Baroni S, Lucidi D, et al. Bacterial biofilms in chronic rhinosinusitis; distribution and prevalence. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:109–112. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1092169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mruwat R, Kivity S, Landsberg R, et al. Phospholipase A2- dependent release of inflammatory cytokines by superantigen- stimulated nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015;29:e122–e128. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corso E, Baroni S, Battista M, et al. Nasal fluid release of eotaxin-3 and eotaxin-2 in persistent sinonasal eosinophilic inflammation. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:617–624. doi: 10.1002/alr.21348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corso E, Baroni S, Romitelli F, et al. Nasal lavage CCL24 levels correlate with eosinophils trafficking and symptoms in chronic sino-nasal eosinophilic inflammation. Rhinology. 2011;49:174–179. doi: 10.4193/Rhino10.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Hong H, Zuo K, et al. Expression of leukotriene and its receptors in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:75–81. doi: 10.1002/alr.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lou H, Meng Y, Piao Y, et al. Cellular phenotyping of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2016;54:150–159. doi: 10.4193/Rhino15.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YT, Chien CY, Tai SY, et al. Asthma associated with chronic rhinosinusitis: a population-based study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016 Jun 29; doi: 10.1002/alr.21813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ledford DK, Lockey RF. Aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-exacerbated chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NM, et al. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:35–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hissaria P1, Smith W, Wormald PJ, et al. Short course of systemic corticosteroids in sinonasal polyposis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with evaluation of outcome measures. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.012. Epub 2006 May 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaidyanathan S, Barnes M. Treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis with oral steroids followed by topical steroids: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:293–302. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alobid I, Benítez P, Cardelús S, et al. Oral plus nasal corticosteroids improve smell, nasal congestion, and inflammation in sino-nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:50–56. doi: 10.1002/lary.24330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oscarsson M, Johansson L, Bende M. What happens with untreated nasal polyps over time? A 13-year prospective study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:710–715. doi: 10.1177/0003489416649971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkins C, Rimmer J, Lund VJ. Does time to endoscopic sinus surgery impact outcomes in chronic rhinosinusitis? Prospective findings from the National Comparative Audit of Surgery for Nasal Polyposis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2015;53:10–17. doi: 10.4193/Rhino13.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masterson L, Tanweer F, Bueser T, et al. Extensive endoscopic sinus surgery: does this reduce the revision rate for nasal polyposis? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1557–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1233-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam K, Kern RC, Luong A. Is there a future for biologics in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis? Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:935–942. doi: 10.1002/alr.21780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Qutob D1. Off-label uses of omalizumab. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:84–96. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauwels B, Jonstam K, Bachert C. Emerging biologics for the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:349–361. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.1010517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]