Abstract

Within biology, molecules are arranged in hierarchical structures that coordinate and control the many processes that allow for complex organisms to exist. Proteins and other functional macromolecules are often studied outside their natural nanostructural context because it remains difficult to create controlled arrangements of proteins at this size scale. Viruses are elegantly simple nanosystems that exist at the interface of living organisms and nonliving biological machines. Studied and viewed primarily as pathogens to be combatted, viruses have emerged as models of structural efficiency at the nanoscale and have spurred the development of biomimetic nanoparticle systems. Virus-like particles (VLPs) are noninfectious protein cages derived from viruses or other cage-forming systems. VLPs provide incredibly regular scaffolds for building at the nanoscale. Composed of self-assembling protein subunits, VLPs provide both a model for studying materials’ assembly at the nanoscale and useful building blocks for materials design. The robustness and degree of understanding of many VLP structures allow for the ready use of these systems as versatile nanoparticle platforms for the conjugation of active molecules or as scaffolds for the structural organization of chemical processes. Lastly the prevalence of viruses in all domains of life has led to unique activities of VLPs in biological systems most notably the immune system. Here we discuss recent efforts to apply VLPs in a wide variety of applications with the aim of highlighting how the common structural elements of VLPs have led to their emergence as paradigms for the understanding and design of biological nanomaterials.

1. WHAT IS A VIRUS-LIKE PARTICLE?

Viruses are elegantly simple systems that exist at the interface of living organisms and nonliving biological machines (Douglas and Young, 2006). Historically studied and viewed primarily as pathogens to be combatted, viruses are now emerging as models of structural efficiency at the nanoscale spurring the development of biomimetic constructs that both directly use viral components and utilize principles learned from virology to achieve a multitude of functions. In particular, engineering of virus structures has allowed for the utilization of self-assembly processes, building of hierarchical materials, design of nanoparticles for biological recognition and delivery, and the compartmentalization of chemical reactions on the nanoscale.

With an ever-growing list of characterized viruses, the total number and variety of viruses are estimated to surpass all other genetically replicating biological systems (Suttle, 2005). Viruses have been discovered in every environment on the planet including extreme temperature, pH, salinity, and pressure. Within characterized viruses an amazing number of strategies for entry into a host, cargo delivery, and escape have been observed all using a canonical viral structure consisting of a protein, or protein and lipid, cage surrounding, and encapsulating a genetic cargo. These structures are typically constructed of many copies of a few structural proteins which self-assemble to form the viral cage. The cage structures of many viruses have been shown to tolerate synthetic or genetic manipulation thus providing a rich library of useful scaffolds for the design and synthesis of biomimetic nanoparticle systems.

Nanoparticle systems have been and continue to be useful components of such broad ranging fields as catalysis, drug delivery, immunology, materials assembly, and environmental remediation to name a few. Nanoparticles offer higher surface area to volume ratios than bulk materials, which translates to more exposed surface for molecular interactions. For biomedical applications, nanoparticles are small enough to travel through vasculature allowing them to circulate and interact at the tissue and cellular level within organisms (Blanco et al., 2015). In catalysis, nanoparticles are large enough to be easily removed from a reaction mixture while still maximizing reactive surface area (Zhou et al., 2009). Depending on the materials being used, the structure and composition of nanoparticles can often be controlled allowing for the design of particles with functions greater than the sum of their parts (Park et al., 2009; Sanvicens and Marco, 2008). While there has been significant development in the area of synthetic nanoparticle technologies, techniques that can perfectly control the spatial arrangement of components within the particle are rare. Many viruses provide structural templates with well-defined particle structures achieved through self-assembly processes.

The core function of the structural cage or capsid of viruses is the protection of the viral genome, but it also facilitates the infection process. Viral capsids are composed of protein subunits and in some cases are surrounded by a phospholipid bilayer. The capsid also provides both an interior and an exterior surface for the protection or presentation of active functional molecules such as proteins whose function in the viral lifecycle is often mediated and accentuated by their location in the virus structure.

The capsid structures of many viruses can be utilized directly for biomimetic engineering. Often cages are utilized in a nucleic acid-free form called a virus-like particle (VLP). VLPs are cage nanoparticles that often maintain the same symmetry as the viral source from which they are derived. VLPs can be derived directly from infectious viruses by removing infectious material, or they can be produced through heterologous expression of structural capsid proteins. The concept of VLPs can also be broadened to include nonviral cage-forming protein systems, which share structural but not functional similarities with viral capsids. Throughout this chapter the term VLP is used generously to include hollow self-assembly protein cages of both viral and nonviral origin. The same concepts of symmetry and repeated subunit–subunit interactions govern the assembly of both viral and nonviral VLPs. Throughout each discussion it will become evident that the structural, catalytic, and biomedical potential of VLP systems are dependent purely on this shared protein cage structure and not necessarily the origins of the VLP system.

Viruses demonstrate unmatched ability to self-assemble from a precise number of identical, or families of identical, subunits into monodispersed particles. The morphology of the resultant particles is programmed into the structures of the protein subunits (Fig. 1). Therefore the blueprints for the virus structure are contained entirely in a relatively small fragment of genetic information, often only a few genes. These self-assembly processes are robust enough that some virus capsids can even be adapted to assemble in vitro from purified protein components. In many cases, virus capsids consist of one or a few proteins repeated symmetrically over the capsid. This simplicity makes viruses much more manageable systems to study than more heterogeneous self-assembling biological structures that occupy the same relative size scale such as vesicles, cytoskeletal components, and cell walls.

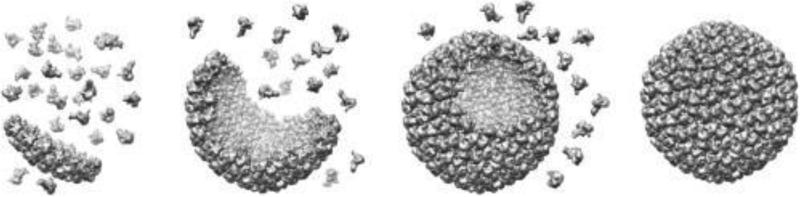

Fig. 1.

Self-assembly of a virus-like particle (VLP). The final structure of a VLP is programed into the genetic sequence of a single or a few structural proteins that self-assemble to form a cage structure. Illustration was generated from PDB: 2XYY (P22 procapsid) but does not authentically reflect the assembly process of P22.

The evolutionary pressures on viruses as minimalist parasitic entities have provided a large variety of nanoparticle structures that all reflect common structural elements. Here we discuss how these structural elements of self-assembly and symmetry make viruses and protein-based VLPs impressive structures and accessible platforms for bioengineering at the nanoscale. We will begin with a discussion of viral structure and the phenomenon of self-assembly including the emerging understanding of viral mechanics and efforts to design synthetic protein capsids de novo. Next we will examine how these self-assembly principles can be applied to larger size-scales through the use of VLPs as building blocks for higher-order materials assembly. Finally we will examine the ability to functionalize the interior and exterior surfaces of viruses and VLPs for a range of engineering applications, in particular focusing on the use of viruses for imaging, small-molecule delivery, catalysis, antigen delivery, and immune modulation. We will limit our discussion to only include protein-based VLPs though there have been numerous successful efforts utilizing membrane-enveloped VLPs as vehicles for delivery of protein cargo within the body (Grgacic and Anderson, 2006; Noad and Roy, 2003). While even within the realm of protein-based VLPs this discussion is not comprehensive, our goal is to describe in general how structural platforms can be borrowed from natural viruses, and other cage-forming structures, and through understanding of their structure and dynamics can be adapted to biomimetically address nanotechnology needs in materials, catalysis, and biomedicine.

2. THE ESSENTIALS OF PROTEIN VLP STRUCTURE

A consequence and mechanism of virus assembly from only a few components is a high degree of symmetry in the resultant cage architectures. In a virus cage, the subunits orient to maximize contacts and distribute stress across the structure thereby minimizing energy. In a spherical virus, this often results in the formation of icosahedrally symmetric cages (Fig. 2) (Zandi et al., 2004). Icosahedral symmetry is dictated by 6 fivefold, 10 threefold, and 15 twofold rotation axes. Assembling an icosahedron out of a single repeated subunit requires that the subunit adopts nonequivalent positions for larger and larger icosahedrons. The number of nonequivalent positions is reflected in the T number, which ascends at allowed integer values for larger and larger capsids. Reflecting these requirements, icosahedral viral cages are made up of 12 pentons and a number of hexons equivalent to 10 (T – 1).

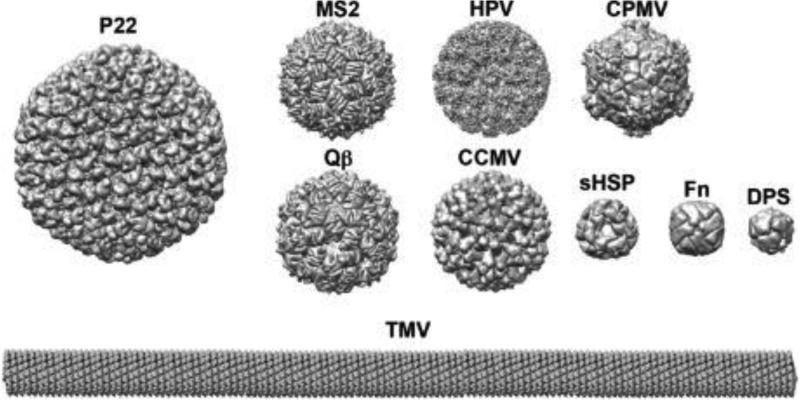

Fig. 2.

VLP structures cover a range of sizes and morphologies providing a library of geometric tools for materials applications. Displayed are some of the VLPs discussed in this review with relative size scale approximately preserved except for TMV, which is shown at half scale compared to the rest of the VLPs. PDB: 2XYY, 2B2G, 1QBE, 5A33, 1ZA7, 3J6R, 1SHS, 2IY4, 3AJO, and 4UDV.

The polyvalency and symmetry of viruses can be thought of as a necessity for doing more with less. Viruses have a limited amount of genetic space to dedicate to structural proteins within the compact viral genome. Larger capsids require more structural proteins and proteins dedicated to aiding in capsid assembly. For instance icosahedrons above a T number of 4 tend to require a scaffolding protein (SP) or scaffolding domain to aid in coat protein assembly. This genetic cost of having a larger icosahedral capsid encourages viruses to develop highly efficient self-assembly processes from minimal components. Even viruses with nonicosahedral symmetry such as rod-shaped viruses must balance the cost of increasing structural size with the benefits of expanding the genome.

Several structural elements arise naturally out of the assembly of viruses. A consequence of the assembly of viruses is that there is a polyvalency of the exposed molecules in the final cage. In a later section we will discuss how this repeated structure impacts viral-host recognition in a nonspecific fashion. As mentioned earlier the term VLP is used in this chapter inclusively of nonvirally derived protein cages and designates any self-assembly protein cage structure. Nonviral spherical VLPs also share repeated subunit structures but, unlike spherical viruses, they exhibit symmetries other than icosahedral. What this means for biomimetic engineering efforts is a new set of templates with different symmetry elements than those offered by the discrete T numbers of the icosahedral viruses. For instance the ferritin cage family of intracellular iron storage proteins features cages composed of 24 identical subunits arranged in an octahedral (four-, three-, and twofold) symmetry. Smaller members of the ferritin family such as DNA-binding protein from starved cells (DPS) adopt a tetrahedral (three- and twofold) symmetry and are composed of 12 subunit monomers. Some nonviral VLPs do assemble with icosahedral symmetry, including the enzyme lumazine synthase (LS) (T = 1), E2 protein (T = 1), and encapsulin (T = 1).

The spherical VLP examples mentioned earlier are structurally isotropic and for some applications this is not conducive to the target application. Fortunately, for those utilizing VLPs as nanoplatforms, the viral world provides alternatives to spherical particles. Certain nonrod-shaped VLPs naturally assume anisotropic structures. Both the family of intracellular ribonucleoproteins collectively called Vaults and the chaperone complex GroEL/ES (Hsp60/10 in eukaryotes) assume elongated cage structures. In addition anisotropy can be introduced into spherical VLP through selective or stochastic methods. Douglas and coworkers used in vitro assembly to create mosaic VLPs by mixing subunits from VLPs of Cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV) or Listeria innocua DPS that had been chemically labeled with different functionalities. By controlling the ratio of different subunits in the assembly mixture, the ratio of different labels in the final VLPs could be controlled (Gillitzer et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2008). Toward a similar end goal Suh and coworkers genetically produced mosaic capsids of adeno-associated virus leading to viruses that contained stochastic mixtures of two mutant versions of the coat protein. By introducing two different sets of coat protein subunits with different protease susceptibilities into the cages, particles could be targeted for decomposition and release of cargo only at sites where both proteases where present (Judd et al., 2014).

In an effort to create spherical janus VLPs that is particles with two distinct faces, Douglas and coworkers masked and labeled an exterior cysteine-containing mutant of the L. innocua DPS particle by reversibly linking it to a surface and selectively modifying unbound, exposed thiols. Two distinct functionalities could be imparted to the VLP in a spatially separated fashion using this strategy (Kang et al., 2009).

Additionally certain spherical VLPs naturally retain or can be made to retain anisotropic elements of their natural parent structures. Ferritin is naturally composed of stochastic mixtures of a heavy and light subunit resulting in a randomly distributed chimeric particle. Spherical phages have a portal complex at one of the fivefold sites of the cage that gives the particle a directionality, and these portal complexes can be incorporated into some of the phage-derived VLPs. Additionally some phage, notably phage T4 and Θ29, naturally adopt elongated (prolate) icosahedral structures (Lee and Guo, 1995; Leiman et al., 2003).

The sheer number of viruses, and related nonviral VLPs, offers a vast library of potential cages of varying shapes and sizes that could in principle all be used as nanoparticle platforms. Structural understanding of VLP candidates, including the dynamics and mechanics of the cage, is essential in intelligently applying different VLPs to different potential purposes.

3. VLPs AS MATERIALS

Viruses must simultaneously form a capsid that is stable enough to encapsulate a self-repulsive polyelectrolyte cargo, protect that cargo in many different environments, remain dynamic enough to deliver that cargo, and do all of this with a minimal genome. These harsh requirements have led to the evolution of very elegant and impressively durable structures that cover a range of different assembly and delivery strategies depending on the host. Before the full potential of these natural structures can be harnessed for biomimetic materials, and their applications, a solid foundation of theoretical and analytical knowledge of viral structure and dynamics is needed.

Efforts to understand the structural potential of viral systems rely on three main targets. First is an understanding of the static viral structure and how the subunits are arranged. Second is an interrogation of the mechanics and stability of the virus structure. Third is an understanding of the dynamics of assembly processes that lead to the formation of the virus cage. In this section we will briefly describe some of the ongoing efforts to monitor virus structure and formation that allow for the further engineering of these remarkable cage architectures.

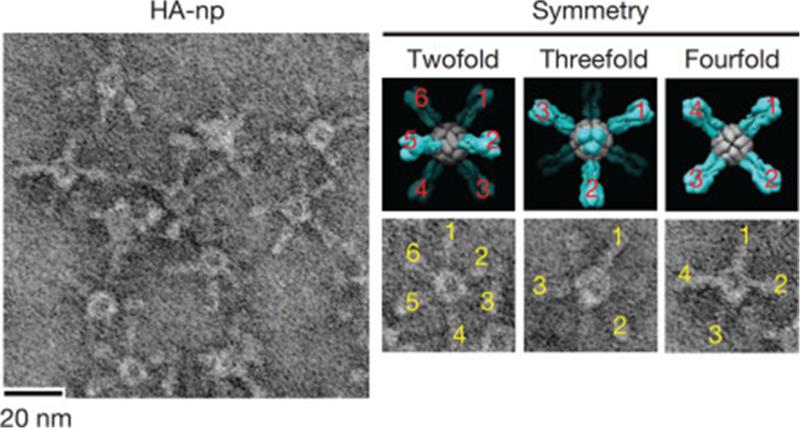

Cryo-transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) and image reconstruction have played an essential role in determining the structure of viral capsids, and in some cases X-ray crystallography has allowed atomic resolution structure determination (Johnson and Chiu, 2000; Lin et al., 1999; Rossmann and Johnson, 1989; Speir et al., 1995). This has led to the visualization of the molecular level arrangement within large multiple megaDalton virus structures. For example structures have been determined for cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) down to 2.8Å resolution providing invaluable guidance in subsequent understanding and redesign of the particle for synthetic applications (Lin et al., 1999). Static structural studies have also been able to approach questions concerning viral dynamics by identifying different morphological states within a virus population during a structural transformation (Gan et al., 2004; Speir et al., 1995). New enhanced EM detectors and the increasing use of single particle tomographic image reconstructions have provided a new revolution in structural characterization of these large macromolecular assemblies (Chang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Difficulties remain in examining asymmetric structures but combinations of these techniques with emerging strategies such as mass spectrometry of viral capsids where the native state of the capsid assembly can be directly probed have begun to overcome the shortcomings of individual techniques (Kukreja et al., 2014; Pierson et al., 2014). Mass spectrometry has also been a powerful tool for the connection of local subunit dynamics with large movements and properties of the capsid (Hilmer et al., 2008).

The strength of some viruses is derived from their symmetric arrangement of subunits to maximize contacts and minimize strain at any given point (Zandi et al., 2004). These structures have been shown to successfully resist pressures as high as 50 atm on the capsid interior (Evilevitch et al., 2003). Additionally, a growing body of mechanical data has been collected probing viruses from the capsid exterior using atomic force microscopy (AFM) to perform nanoindentation experiments (Roos and Wuite, 2009). These studies continue to show that even against exterior compression certain viruses are remarkably strong. The strength of the viral capsid has been shown to closely reflect the mechanism of viral genome packaging. Viruses that form a capsid precursor or a procapsid prior to genome packaging are consistently stronger and stiffer than viral capsids that assemble around their genome (Roos et al., 2007). Considering the structural requirements of these two families of viruses this disparity makes sense. Procapsid-forming viruses are typically loaded with a genome through a nucleic acid portal or pump and release their genome through the same pore using an injection mechanism to translocate the genome into a host cell. In this mechanism, once the capsid formed it does not need to come apart again; however, it does need resist the considerable pressure exerted on the capsid interior as the genome is actively pumped in thus these structures require more rigidity and strength. Viruses that form around their genome often deliver their genome through disassembly within a cell or a cellular compartment. As such they need to be dynamic and do not need to resist as much pressure because the genome is not pumped in but instead condenses with the capsid during assembly. Coarse grain simulations are able to replicate these trends (Gibbons and Klug, 2007). Observations such as these provide guidance in selecting natural viral systems for materials applications depending on the need for dynamics or rigidity.

The spatial resolution of nanoindentation experiments has also provided support for in silico models of viruses and the symmetrical distribution of stress about the capsid (Castellanos et al., 2012). AFM studies in which virus particles are stressed to their breaking point while simultaneously imaging the points of failure, have shown preferential expulsion of pentons, which are predicted to be the points of highest stress or defects in the subunit lattice of the capsid. Additionally, the mechanical assessment of capsids along different axes in the line of compression has shown that VLPs are not isotropic with respect to stiffness or strength (Carrasco et al., 2006, 2008; Hernando-Pérez et al., 2014b).

3.1 Controlling the Self-Assembly Process

The assembly of viruses from a minimal set of subunits is an excellent example of efficient use of genetic space and regulated self-assembly where the final structure of the material is programed into the sequence and structure of the subunits. In the case of viral capsids the size, symmetry, and shape of the capsid is dictated by the structure of a few structural proteins. Toward examining viral assembly, numerous efforts have examined the ability of viral coat proteins to assemble in the absence of cargo (Bancroft et al., 1967; Casini et al., 2004; Zlotnick, 1994; Zlotnick et al., 2000). However, the assembly process is often also dependent on interaction with the nucleic acid cargo or other structural proteins that template the assembly of the capsid proteins. In this vein, both experimental and in silico efforts have focused on elucidating the mechanisms of viral assembly in the presence of cargo (Johnson et al., 2004; Nguyen et al., 2007). A growing number of studies are approaching the assembly process using templates consisting of natural or synthetic cargos of defined size. These studies begin to examine and take advantage of the relative contributions of the cargo–coat interaction compared to the subunit–subunit interaction in the assembly process.

Dragnea and coworkers have taken advantage of the reversible in vitro assembly of brome mosaic virus (BMV), in which capsid assembly is templated through relatively nonspecific electrostatic interactions between coat proteins and the nucleic acid cargo, to examine the potential for size-templated capsid assembly (Sun et al., 2007). By utilizing gold nanoparticles of defined sizes, decorated with polyethylene glycol having a negatively charged terminus as a substitute for the natural nucleic acid cargo, BMV VLPs of different sizes could be produced each retaining icosahedral symmetry but with T numbers dependent on the size of the cargo. This structural flexibility was not unique to the gold nanoparticle cargo, and functionalized iron oxide particles could be encapsulated in a similar fashion (Huang et al., 2007). While the natural morphological flexibility of BMV lends itself to these studies, the finding that cargo–coat interactions can modulate coat–coat interactions and dictate the resultant structure that highlights the broad potential for expanding the structural versatility of individual VLPs.

3.2 De Novo VLPs

Cages are formed through the coordination of symmetric interactions. In the case of an icosahedron, the structural template of spherically symmetrical viruses, the most basic set of interactions needed to make a closed shell cage architecture from a single repeating subunit are reflected in a T = 1 particle, having 60 subunits with five-, three-, and twofold rotational symmetry. Simpler nonviral VLPs adopt alternative cage symmetries such as ferritin, which assembles with octahedral, four-, three-, and twofold rotational symmetry. Each of these families of VLPs is defined by a specific set of symmetric subunit–subunit interactions. With this in mind, efforts have been successful toward designing new cages by fusing protein domains with known or anticipated quaternary structure.

Yeates, Baker, and coworkers have designed several protein cage systems by combining protein domains with a known propensity to adopt defined quaternary structures (two-, three- or fourfold interactions). By combining simulations from the protein prediction and design software Rosetta with genetic constructs, these efforts have produced cages with defined octahedral or tetrahedral symmetry (Fig. 3) (King et al., 2012). Extending these techniques they successfully designed cages composed of two distinct protein subunits, expanding the available complexity of their approach (King et al., 2014). While currently still limited to relatively small and simple cage architectures, de novo design of ever more complex capsids is likely to become accessible through precise understanding of the necessary subunit interactions.

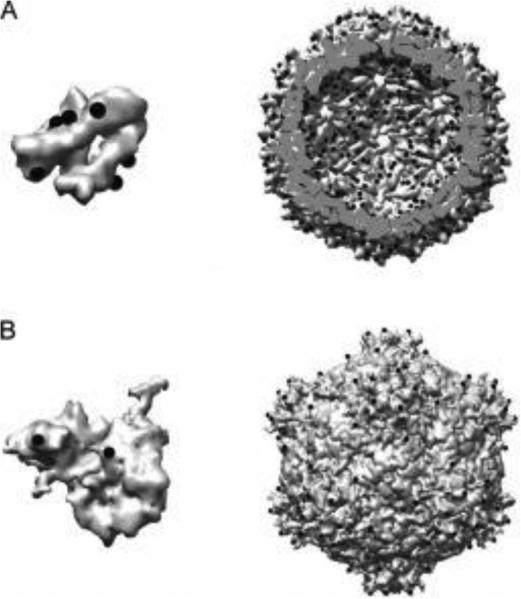

Fig. 3.

In silico design can produce novel VLP structures by engineering novel subunit interfaces. Three example crystal structures of two component VLPs designed by Baker and coworkers. Cages are designated as (A) T33-15 (PDB: 4NWO), (B) T32-28 (PDB: 4NWN), and (C) T33-21 (PDB: 4NWP). In each cage, subunits are colored by subunit type (King et al., 2014).

3.3 Higher-Order VLP Assemblies

In addition to their impressive material properties as nanoparticles, VLPs have been shown to be effective building blocks for the construction of higher-order materials. Nature builds from the molecular level upward through increasingly complex structures enabling the construction of intricate systems with hierarchical layers of function and controlled mechanical properties. While synthetic materials engineering efforts are beginning to utilize naturally self-assembling structures such as VLPs, or inspiration from these systems, to design and construct materials from the bottom up. VLPs are tolerant of modification on the interior and exterior of the cage. Interior modification, both genetic and synthetic, can lead to changes in the mechanical characteristics of the cage or can incorporate some functionality such as a catalyst. Modification of the cage exterior can introduce linker molecules leading to higher-order assembly.

Two-dimensional arrays of VLPs can be assembled with or without modifying the surface of the cages. Several studies have successfully generated two-dimensional arrays of VLPs on solid surfaces by first allowing the VLPs to assemble at liquid interfaces using Langmuir–Blodgett methods (Yamashita, 2001; Yoshimura et al., 1994). Using nanolithography techniques, spherical VLPs have also been arrayed in controlled patterns directly onto solid substrates (Cheung et al., 2003). Layered assemblies of spherical VLPs can be generated through electrostatic or specific noncovalent interactions (Suci et al., 2006).

The anisotropic shape of rod-shaped viruses and VLPs lends itself to alignment at high concentration or when interactions between VLPs are facilitated. Rod-shaped cages have been arrayed in solution and on solid substrates using a variety of techniques. M13 phage has been organized into fibers using electrospinning techniques resulting in aligned bundles with diameters of 10–20 μm (Lee and Belcher, 2004). Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) naturally coordinates divalent metal cations and can be dried as an ordered array in the presence of Cd2+ (Nedoluzhko and Douglas, 2001). Lee and coworkers have exhibited considerable control over M13 phage deposition as liquid crystal patterns on solid surfaces. By pulling substrates out of an M13 solution with variable speeds, the combination of friction and surface tension at the meniscus led to deposition and alignment of the anisotropic particles (Chung et al., 2011). The organization, chirality, and density of bundles within these assemblies were used to create surfaces with controlled optical properties. The surfaces could also be used for selective immobilization of cells and templated biomineralization. Similar assemblies of M13 could be used to generate electricity through physical bending of the material because of the piezoelectric nature of the cage assemblies during deformation (Lee et al., 2012).

Three-dimensional assemblies of VLPs have also been successfully generated in solution (Fig. 4). Corneliessen and coworkers utilized optically sensitive dendrimers to assemble the CCMV VLP in a highly ordered fashion without modifying the cages themselves (Kostiainen et al., 2010). These assemblies could be selectively disassembled with light through the photochemical decomposition of the dendrimers. Utilizing a metal coordination strategy to link individual cages into an extended 3D array has been explored in both the tetrahedral DPS protein and the octahedral Ferritin protein cages, where Fe or Zn ions were used to bridge between metal-binding sites on individual proteins (Broomell et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Hierarchical assembly of VLPs can be facilitated through direct VLP contacts or molecular mediators in the form of dendrimers, inorganic nanoparticles, or other VLPS. VLPs, which are themselves an assembly of subunit monomers, can be made to assemble into extended structures and under certain conditions the structures can be ordered. The use of molecular mediators is a common route toward assembly as it allows for the agglomeration of identical particles through properties such as charge.

To incorporate specificity into the 3D assembly of individual VLP-based materials, Finn and coworkers covalently attached complementary oligonucleotides to the surfaces of two different populations of CPMV VLPs. When these complementary VLP populations were mixed the nucleotide sequences base-paired leading to extensive oligomerization and the formation of a VLP network (Strable et al., 2004). In another capsid-specific strategy, an exterior decoration protein (Dec) was linked as a head–head dimer, through cysteine-mediated sulfide linkages, which was able to mediate interactions between P22 VLPs. This ditopic Dec–Dec linker, when mixed with the P22 VLP, lead to the assembly of an unstructured P22 assembly. However, a layer-by-layer approach, with alternating Dec–Dec and P22 layers could be readily formed using these materials (Uchida et al., 2015). The system could be extended to make a binary cage assembly through genetic fusion of Dec to the tetrahedral DPS protein leading to DPS VLPs with four exposed P22-binding Dec domains which could act as tetratopic linkers for the assembly of P22 VLPs.

An ongoing challenge in the incorporation of VLP into bulk materials is the construction of highly ordered assemblies in three dimensions. Ceci and coworkers utilized gold nanoparticles as mediators in the assembly of either CCMV or ferritin cages into an extended lattice. VLPs and gold nanoparticles assembled through interactions between charged patches on the VLP surface and the isotropically charged gold particles (Kostiainen et al., 2013). An interesting suggestion of these strategies, including both gold nanoparticle and dendrimer-mediated assembly, is that size matching and charge anisotropy can be used to advantage to direct highly ordered assemblies in a range of VLP systems (Doni et al., 2010; Kostiainen et al., 2010, 2013).

4. VLPs AS TEMPLATES FOR CONSTRAINED MATERIAL SYNTHESIS

4.1 Mineralization

In addition to acting as building blocks for materials, VLPs can also naturally function as containers for the constrained synthesis of nanoparticles composed of other materials. Some nonviral VLPs, which maintain a self-assembled protein cage architecture similar to a virus, are known to template nanoparticle synthesis naturally, most notably the iron storage protein cage ferritin. Ferritin is a small spherical VLP with octahedral symmetry. Ferritin is nearly ubiquitous in nature where it catalyzes the oxidation and storage of iron, which can be toxic to the cell (Uchida et al., 2010). The same protein subunits that provide the structure of the cage also contain the enzymatic ferroxidase sites and provide high charge density nucleation sites for the formation of the resultant iron oxide nanoparticle. The exterior of the ferritin cage is nucleation inert and pores in the cage enable ions to traverse the shell and reach the interior. All of these requirements are facilitated by a simple protein subunit that when assembled into the closed shell cage acts to coordinate these functions.

In vitro studies of the ferritin mineralization process have shown promiscuity toward several unnatural mineral nanoparticles, dependent on the reaction conditions. Ferritin promotes the formation of a kinetically trapped polymorph of iron oxyhydroxide (ferrihydrite) under biological conditions. Approaches have been developed that utilize empty ferritin (apo-ferritin) to access alternative iron oxide polymorphs by changing the reaction conditions. Using these principles a wide variety of other nonnatural minerals have been successfully nucleated and grown within ferritin cages (Allen et al., 2003; Douglas and Stark, 2000; Klem et al., 2008; Meldrum et al., 1995; Uchida et al., 2010).

In addition to the direct use of ferritin, other VLPs have been shown to facilitate mineralization based on the strategies inspired by the ferritin system. Many viruses have a naturally complex charge distribution and, importantly for mineralization, have a distinct charge distribution on the interior vs the exterior of the cage. Viruses that assemble around their genome recruit and interact with their nucleic acid cargo often through positively charged residues or specific sites (Božič et al., 2012). Studies using the CCMV have shown that a variety of different inorganic nanoparticles can be synthesized within the naturally positively charged interior of CCMV (Douglas and Young, 1998, 1999; Klem et al., 2008). Alteration of the electrostatics on the capsid interior has been shown to facilitate the nucleation and growth of a different range of inorganic nanoparticles inside CCMV.

The exterior surface of VLPs also enables the templating of materials synthesis. Unmodified phage T4 particles have been silicified controlling their infectious potential (Laidler and Stedman, 2010). Rod-shaped viruses including TMV and bacteriophage M13 have been used as templates for external mineralization (Mao et al., 2004; Shenton et al., 1999). In some cases the coat protein can be genetically modified to direct-specific recruitment of mineral species.

4.2 Constrained Polymerization

In addition to the formation of inorganic nanoparticles, the interior space of VLPs also provides for the templated and constrained synthesis of polymer networks. Virus capsids have evolved to confine an extended biopolymer in the form of the viral genome. Despite restricting the escape of large polymers, virus cages remain largely permeable to small molecules. This feature enables polymerization localized to the interior of the VLP by selective reaction of monomers at initiation sites on the interior of the cage. The genetic origin of VLPs enables ready site-directed mutagenesis for the introduction of multiple polymer-initiation sites selectively on the interior and exterior of the cage. Certain VLPs are remarkably tolerant to organic solvents and harsh reaction conditions. As such the available methods for labeling the cage with an initiation site and polymerizing the interior are numerous.

Adding a polymer to the interior or exterior of a VLP cage can serve multiple purposes. Polymers allow for a change in the mechanical and chemical signature of the capsid without altering the self-assembly process, they enable the introduction of new chemical moieties beyond the canonical amino acid side chains, and they more efficiently make use of the volume provided by the VLP assembly. The available sites for labeling an unmodified VLP with a molecular cargo are more or less distributed on a two-dimensional shell, which poorly utilizes the volume enclosed by the particle. By polymerizing the interior or exterior of the cage the number of sites available for labeling can be increased and extended into the confined or surrounding volume.

Stepwise polymerization strategies on biochemical scaffolds offer an unmatched degree of control and uniformity in the final products but are time intensive. A branched “click” copolymerization strategy was utilized through 3.5 generations to create a polymer-filled small heat-shock protein (sHSP) from Methanococcus jannaschii (Liepold et al., 2009). sHSP is a small nonviral VLP (12 nm diameter 400 kDa) that acts in a chaperone-like capacity to decrease heat-induced protein aggregation (Kim et al., 1998). Internal polymerization led to an additional 200 amine sites, which could be subsequently functionalized with cargo for MRI contrast enhancement.

VLP-templated polymerization is particularly useful toward controlling the extent of polymer growth in the case of so-called “living” polymerizations. In these strategies polymerization will continue until precursors are depleted or until a termination step occurs (De Jong and Borm, 2008; Wang and Matyjaszewski, 1995). While much faster than stepwise polymerization, these strategies lack precise control in the final product. One strategy to increase the regularity of living polymerization products is to template the polymerization within a nanocontainer.

The constrained atom-transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) of 2-aminoethyl methacrylate (AEMA) within the bacteriophage P22 VLP was a first demonstration of this approach. Tertiary bromide radical initiation sites were covalently attached to the interior of the cage in a site-specific manner, by way of selective point mutations, and used to direct polymerization, which was constrained to the interior of the cage. The resulting particles contained 12,000 ± 3000 AEMA monomers per particle which could be functionalized to deliver large payloads of fluorescent dyes or MRI contrast agents (Fig. 5) (Lucon et al., 2012).

Fig. 5.

The interior space of the P22 VLP can be utilized by introducing a scaffold via atom-transfer radical polymerization. The radical initiator 2-bromoisobutyryl aminoethyl maleimide was coupled to an internal cysteine of the P22 coat protein. Polymerization of the capsid interior with 2-aminoethyl methacrylate (AEMA) introduced as many as 9000 amine sites within the intracapsid space. These sites could then be functionalized with Gd-DPTA-NCS resulting in high particle loading (Lucon et al., 2012). Figure used with permission from Lucon, J., et al., 2012. Use of the interior cavity of the P22 capsid for site-specific initiation of atom-transfer radical polymerization with high-density cargo loading. Nat. Chem. 4, 781–788.

Finn and coworkers have demonstrated both interior and exterior polymerization of the Qβ VLP using ATRP. In either case an azide-containing moiety could be introduced to the interior or exterior of the cage to which an alkyne with an ATRP initiating tertiary bromide could be attached using a Click reaction. Selective polymerization allowed for targeted biological functionalization including siRNA delivery (interior) and imaging or drug delivery (exterior) (Hovlid et al., 2014; Pokorski et al., 2011).

The exteriors of rod-shaped viruses have also been addressed with polymers. In the case of TMV and M13, Wang and coworkers have demonstrated that noncovalent association of precursors with the cage surface leads to controlled polymerization of poly-aniline on the exterior of the VLPs. A useful side effect of this particular strategy is that the polymerization also mediated the head-to-tail assembly of multiple VLPs into an extended polymer-coated nanofiber of up to 20 μm in length, which could be further functionalized (Niu et al., 2006, 2008).

5. VLPs FOR BIOMEDICAL DELIVERY AND IMAGING

Nanoparticles can be used to mask the characteristics of a cargo, which are supplanted by the characteristics of the nanoparticle. This holds true for the chemical, mechanical, and shape/size characteristics of the cargo-loaded nanoparticle. Thus, polymeric nanoparticles have been used to increase the solubility and availability of a cargo in a variety of different systems, notably pharmaceutical delivery of hydrophobic pharmaceutical drug molecules (De Jong and Borm, 2008). VLPs offer a biological alternative to synthetic nanoparticles for cargo loading and delivery.

As discussed previously VLPs provide modifiable surfaces on both the interior and exterior of the particle. Conjugation of cargo to either of these surfaces can be pursued synthetically, genetically, or through a combination of the two. Routes toward bioconjugation of cargo can take advantage of existing amino acid side chains, introduced amino acids, and introduced nonnatural amino acids or peptide termini (Ma et al., 2012). Some VLPs are tolerant of organic solvents, increased temperature, and large ranges of pH making them compatible with a wide variety of reaction conditions.

By loading a soluble cargo into a nanoparticle, the payload of that cargo upon reaching a target is increased. In the case of a drug candidate, if 100 molecules per cell are required for a desired effect then 100 separate molecules have to independently reach that cell. However if a nanoparticle is loaded with 100 molecules, every nanoparticle that reaches a cell will theoretically deliver the required payload and have the desired effect. Additionally the multiple surfaces and unique chemical groups afforded by some nanoparticles allows for simultaneous attachment of both a set of cargo molecules and set of targeting molecules causing accumulation of the particles at a specific site (Schwarz and Douglas, 2015).

Effects such as this increased payload per particle are particularly appealing for pharmaceutical delivery and imaging. All imaging techniques rely on the ability to resolve a target area or features of interest from the surrounding environment. If a contrast agent can be bound selectively at a point of interest the detection limits of the technique can be significantly enhanced.

At times VLPs provide biomedical delivery functionality beyond their natural function without the need for any redesign or modification. The cage-like architecture of ferritin and its ability to encapsulate cargo has been adopted to deliver gadolinium contrast agents (Aime et al., 2002) and platinum-containing cancer drugs (Yang et al., 2007). In the case of viral-derived VLPs, Bachman and coworkers utilized the natural nucleic acid-binding ability of VLPs from hepatitis B core (HBV) antigen or bacteriophage Qβ to deliver immune stimulatory nonmethylated CG motifs (Storni et al., 2004). Delivery of other nucleic acid therapeutics can also be achieved through the use of unmodified VLPs (Pan et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2005). The natural calcium-binding sites of CCMV were used for the binding of gadolinium as a MRI contrast agent resulting in a loading of 140 Gd per particle and a 10-fold increase in the efficiency of each Gd as a result of being complexed with the VLP (Allen et al., 2005). CCMV has also been shown to encapsulate water-soluble porphyrins during in vitro reassembly. Fortuitously the interior of the capsid stimulates aggregation of the cargo in this case preventing escape into the bulk without the need to chemically attach the molecules to the capsid (Brasch et al., 2011).

Viruses with nucleic acids still loaded have also been repurposed for the delivery of molecules that naturally associate with the genome. Loading and delivery of a variety of fluorescent dyes as well as the therapeutic proflavine has been accomplished in CPMV via association with the encapsulated nucleic acid (Yildiz et al., 2013). Similar strategies were applied to cucumber mosaic virus to deliver doxorubicin (Zeng et al., 2013). Toward MRI contrast enhancement, the natural affinity of lanthanides for nucleic acids was exploited to load Qβ and CPMV with Gd and, in the case of Qβ, the capsids were further loaded with Gd through azide–alkyne Click conjugation of a Gd-chelate to specific sites on the capsid (Prasuhn et al., 2007).

In the more common case where a target cargo does not have a natural affinity for the VLP, covalent attachment is by far the most universally exploited strategy for attachment of small-molecule cargos to VLPs (Ma et al., 2012). Because of the repeated subunit structure of VLPs, reactive sites, in the form of either native or nonnatural amino acids, are at least as numerous as the number of subunits (Fig. 6). The success of this strategy is highly dependent on the bioconjugation reactions available for labeling and the resolution of available capsid structural information for design. While labeling location can be determined empirically, a previous understanding of the location of sites within the protein structure greatly enhances the ability to label the capsid in a way that ensures the cargo is localized to the interior or exterior (Bruckman et al., 2013; Lucon et al., 2012).

Fig. 6.

The symmetry of VLPs reflects a single change over the entire particle. (A) Nonspecific labeling of lysines in the MS2 capsid has the potential to label six sites (shown as black spheres) per subunit (left), which are reflected as 1080 total sites on both the interior and exterior of the capsid the assembled capsid (right) (Anderson et al., 2006). (B) Greater specificity can be introduced through site-directed mutagenesis such as the cysteine-containing loops inserted by Finn and coworkers into the both the large and small subunit of CPMV (asymmetric unit at left). These mutations are translated about the assembled capsid resulting in spatially precise labeling of the capsid (right) (Wang et al., 2002a). PDB: 2B2G and 5FMO.

One of the earliest virus-derived VLPs to be used in bioconjugation strategies was CPMV. CPMV offers a VLP system that can be easily produced, has a large body of high-resolution structural characterization, and is stable to a wide variety of perturbations (Montague et al., 2011). Initial studies labeling CPMV utilized native lysine residues to attach poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) (Raja et al., 2003), biotin, or fluorescent molecules (Wang et al., 2002b) providing control over particle immunogenicity, detection, and enabling the assembly of higher order viral materials. Higher specificity in labeling could be introduced through specific cysteine point mutations (Wang et al., 2002a). It was demonstrated that CPMV labeled with various fluorescent dyes is highly effective in imaging the vasculature. Further examination showed that the VLP is predisposed to the vasculature through specific interaction with the intermediate filament protein vimentin (murine or human) on the surface of endothelial cells providing it with a natural targeting mechanism not common to other VLPs (Koudelka et al., 2007, 2009).

Studies utilizing bioconjugation strategies have also demonstrated the diverse utility of bacteriophage MS2 toward cargo delivery and cellular targeting (Anderson et al., 2006; Ashley et al., 2011). Combining templated VLP assembly around a cargo and covalent labeling of capsid proteins Peabody and coworkers functionalized MS2 with combinations of targeting peptides, quantum dots, siRNA, ricin toxin, and doxorubicin. In cell culture, these multifunctional MS2 VLPs could selectively kill target cells without damaging spectator cells (Ashley et al., 2011). Francis and coworkers utilized orthogonal bioconjugation strategies to selectively label MS2 with different functional molecules on the interior and exterior of the cage. Using chemistry targeted to either reactive amines or tyrosines, they demonstrated selective presentation of targeting and masking molecules on the exterior and fluorescein as a model small molecule on the interior (Kovacs et al., 2007).

Rod-shaped VLPs have been used as scaffolds for a wide variety of small-molecule conjugation. Toward enhancing the payloads of small molecules rod-shaped viruses have the advantage of being assembled from more protein subunits in the native virus. For instance TMV is composed of 2130 subunits of the primary coat protein whereas the T = 7 bacteriophage P22, one of the larger spherical capsids discussed here is composed of only 420 subunits. While rod-shaped viruses offer less internal space per subunit the sheer number of subunits translates to more native sites for conjugation directly to the VLP. Covalent attachment of Gd chelates to the interior or exterior of the TMV VLP as well as to a thermally induced, disordered TMV spherical particle morphology has resulted in some of the largest measured loading factors for a small-molecule MRI contrast agent in a VLP (Bruckman et al., 2013).

As discussed earlier, a problem is encountered as larger VLPs are used for cargo encapsulation; the encapsulated volume in the VLP vastly exceeds the volume that can be occupied by cargo molecules conjugated directly to the interior particle wall. To overcome this problem of wasted space, polymerization of the interior of VLPs provides a means to fill the interior volume and provides more conjugation sites for cargo attachment. Polymerization of cage interior and exterior surfaces has been effectively utilized to increase payloads of MRI contrast agent and small-molecule drugs (Hovlid et al., 2014; Lucon et al., 2012; Pokorski et al., 2011).

5.1 Masking of VLPs

Just as it can be useful to target nanoparticles to a specific site or tissue, it can be just as beneficial to prevent nanoparticles from going where they are not supposed to. An ongoing problem with the use of VLPs and other nanoparticles in biological systems is that these particles are immune active. Not surprisingly these particles can confuse the immune system, which has developed to recognize nanoparticle-sized pathogens. This inherent recognition by the immune system can be put to beneficial use and will be discussed in a later section. However, for applications that include imaging and/or targeted delivery to nonimmune cells, this problem must be overcome before these technologies can be effectively utilized.

Two primary strategies have been explored to mask particles from immune recognition. The first is to passivate the surface of particle with an immunologically inert molecule. The most common example of this by far has used PEG to coat the particles. Alternatively strategies have been developed that specifically engage cellular machinery that prevent recognition or uptake.

While PEGylation is a well-established particle masking strategy, there are few systematic studies of the effects of PEG in VLPs. Manchester and Steinmetz have shown that masking CPMV from cellular uptake through PEG conjugation is dependent on the size of the attached PEG (Steinmetz and Manchester, 2009). Steinmetz and coworkers later showed that the length and degree branching of PEG conjugated to potato virus X significantly affected the organ distribution and rate of clearance of the particles after intravenous injection (Lee et al., 2015).

Using a targeted masking approach, Douglas and coworkers demonstrated that a minimal self-peptide mimic of CD47 can be presented on the surface of the P22 VLP to avoid uptake by macrophages (Schwarz et al., 2015). This peptide has been shown to specifically engage SIRP-α on the surface of macrophages and actively counteract engulfment (Rodriguez et al., 2013).

In the case of VLPs, masking the immune response raised to the administered particles is particularly difficult because VLPs retain the repeated arrangement subunits characteristic of viral pathogens that host immunity has evolved to recognize and combat. Strategies such as PEGylation and receptor-specific masking may provide enough control over circulation time in vivo for applications of these systems that require only short residence times. Nonetheless the active recognition of VLP particles remains problematic. While targeting molecules can lead to passive accumulation of designed VLPs at a site of interest, effective circulation is still necessary to get the particle to that site. Rarely if ever do targeting molecules lead to active transport to a site of interest. Even targeted VLPs are shown to circulate into the lymphatic system and are also found to accumulate in the spleen and liver (among other organs). For therapeutic applications VLPs may be better used as delivery systems to the immune cells with which they are predisposed to interact. Applications that utilize the natural similarity of VLPs to viruses to pursue effector functions within the immune system will be discussed in Section 7.

6. VLPs AS METABOLIC COMPARTMENTS

The natural nanomaterial properties of VLPs enable them to be used to model the impact of structure within elements of biology and chemistry. Metabolic systems provide the energetic backbone of cellular life (Jeong et al., 2000; Sweetlove and Fernie, 2013). The spatial arrangement of enzymes within this web of sequential and competing reactions provides control over chemical flux and allows for division of resources between different pathways (Conrado et al., 2008; Hrazdina and Jensen, 1992; Pérez-Bercoff et al., 2011; Sweetlove and Fernie, 2013). Structural compartmentalization is a largely untapped resource for the design of biomimetic catalytic systems as well as an essential gap in the understanding metabolism at a molecular level within the cell. In order to access this resource, systems are required that can control the spatial arrangement of enzymes on the nanoscale. In this section we will discuss the appeal of structurally organized catalytic systems and how VLPs can be used as platforms for both catalytic confinement and colocalization.

6.1 Why Encapsulate?

The interior of the cell is a very dense environment with 30–40% of the membrane-confined space occupied by macromolecules (Ellis, 2001). Often the kinetics of metabolism are studied in the form of isolated enzymes in relatively dilute solutions (less than 1 mg/mL) (Eggers and Valentine, 2001; Ellis, 2001; Minton, 2001). This creates an obvious discrepancy between how these catalysts might act inside a cellular environment and how they are typically studied. Unfortunately enzymes are hard to study under highly concentrated conditions. In addition, cellular structures are dynamic and heterogeneous making study in situ difficult. To approach the biophysical characterization of structural elements in metabolism, significant simplification is required. VLPs provide a tightly controlled structural scaffold that can be precisely modified to incorporate cargo and thus offer platforms for both studying and utilizing structure in complex catalytic systems.

Within metabolism, metabolic pathways are facilitated through the separation or colocalization of enzymes. Colocalization can be thought of on different length scales within the cell, first at the microscale with two sequential enzymes being in the same cell or in the same organelle. However the distribution of enzymes within an organelle or the cytosolic space is not homogenous. Colocalization on the nanoscale is mediated by specific enzyme–enzyme interactions or enzyme–scaffold interactions. Specific metabolic agglomerations of sequential enzymes, known as metabolons, allow for more efficient transfer of metabolic intermediates (Jørgensen et al., 2005). Metabolons can be structurally dynamic relying on specific binding interactions among enzymes or between enzymes and secondary proteins or macromolecular scaffolds.

Bridging the gap between organelles and metabolons are a class of organelle-like protein compartments termed bacterial microcompartments (BMCs), which utilize VLP structures to encapsulate and colocalize metabolic elements. BMCs can be thought of as a bacterial organelle, which incorporates the element of confinement while also enforcing nanoscale colocalization.

BMCs were first identified in cyanobacteria in the 1960s when icosahedral compartments within the cytosolic space were found to contain the enzymes carbonic anhydrase and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (rubisco). These icosahedral BMCs termed carboxysomes are thought to concentrate CO2 around rubisco within the cage by carbonic anhydrase-mediated conversion of soluble carbonate. The notoriously inefficient rubisco can be deactivated by O2 and colocalization within the carboxysome likely protects it from the deactivation as well as increases the pathway efficiency by increasing local substrate concentration.

Other BMCs have since been discovered including the ethanolamine utilization (EUT) compartment and the propanediol utilization (PDU) compartment (Cheng et al., 2008). The common metabolic factor linking these BMCs is the presence of volatile or low abundance intermediate in the encapsulated pathway. This leads to the possibility that these cages are acting to prevent the diffusion of escape of the intermediates and allow it to be preferentially processed by the next enzyme in the pathway. This observation suggests that there is also a significant confinement element to BMCs beyond defined colocalization.

While efforts to readapt these BMC cages to encapsulate alternative enzyme cargo, they remain fairly specialized to the enzymes that they naturally encapsulate (Choudhary et al., 2012). However BMCs have a striking structural similarity to icosahedral VLPs (Fig. 7). Efforts have been fruitful toward creating versatile enzyme encapsulation platforms utilizing VLP, which have superior stability and easy of production compared to BMCs.

Fig. 7.

The structural similarity of BMCs and VLPs. (A) A model of the carboxysome based on subunit crystal structures and EM analysis of global structure shows a T = 75 icosahedron (740 hexamers, 12 pentamers) approximately 115 nm in diameter. (B) A cryo-EM reconstruction of the P22 VLP in the expanded form (PDB: 2XYZ) shows a T = 7 icosahedron (60 hexamers, 12 pentamers) approximately 60 nm in diameter. Images are approximately to scale. (C and D) Transmission electron micrographs showing the carboxysome and the expanded P22 VLP, respectively. Scale bars are 50 nm. Figure adapted from Tanaka, S., et al., 2008. Atomic-level models of the bacterial carboxysome shell. Science 319, 1083–1086.

6.2 Methods of Enzyme/Protein Encapsulation

As mentioned earlier, there have been efforts to redesign BMCs for non-native cargo encapsulation. Yeates and coworkers identified an N-terminal 18 amino acid encapsulation sequence in propionaldehyde dehydrogenase (part of the PDU BMC). By fusing that sequence to GFP, glutathione S-transferase, and maltose-binding protein, they effectively directed the encapsulation of these targets within the PDU microcompartment (Fan et al., 2010). Schmidt-Dannert and coworkers were successful in heterologously expressing the EUT from Salmonella enterica and utilizing an encapsulation peptide to direct the encapsulation of a β-galactosidase enzyme (Choudhary et al., 2012).

Viral VLPs offer a similar protein cage structure that might be exploited to encapsulate enzymes. Unlike BMCs, VLPs are often mechanically tough structures and many are known to assemble in vitro. As a simplest case enzyme cargo can be targeted for encapsulation in a completely nonspecific statistical fashion.

In statistical encapsulation, the VLP assembly is carried out in a high enough concentration of the cargo that the assembling cage has a chance to grab cargo molecules by chance (Fig. 8A). All that is required to statistically encapsulate a cargo is a VLP assembly process that can be controlled to occur in the presence of the cargo. While this approach is ideally achieved in vitro with VLP systems that can be reversibly assembled, it could conceivably be achieved in an in vivo setting, if the cargo was at high enough concentration in the cellular environment.

Fig. 8.

Statistical vs directed encapsulation. In a statistical encapsulation process (A), the capsid assembly is triggered in the presence of a cargo and some of the cargo ends up in the capsid as a function of the cargo and coat protein concentrations. In a directed encapsulation process (B), the cargo contains a specific tag or directly fused to the coat protein. The cargo associates with the coat protein prior to assembly and, ideally, triggers or directs the encapsulation process resulting in a more controlled particle formation and higher density packing.

CCMV has presented an ideal system for statistical encapsulation because the capsid assembly process is reversible and well understood. CCMV can be disassembled into subunit dimers at neutral pH (pH 7.5) and subsequently reassembles into a T = 3 capsid upon lowering the pH (pH 5.0). Utilizing a statistical approach, Cornelissen and coworkers encapsulated a single horseradish peroxidase enzyme within the CCMV VLP (Comellas-Aragones et al., 2007). To impart a directed encapsulation element to this CCMV in vitro strategy, the system was later modified with a genetically introduced heterodimeric coiled-coil noncovalently linking the coat protein to the cargo (Minten et al., 2009). This technique led to successful encapsulation of eGFP and Pseudozyma antarctica lipase B (PalB) (Minten et al., 2011). This incorporation of a coiled-coil linker encourages recruitment of cargo and improves encapsulation compared to a statistical encapsulation. However in order for successful CCMV VLP assembly to be achieved free wild-type coat protein had to be added to the assembly mixture of each of these constructs, presumably due to the steric limitations of assembling a capsid from coat proteins that are all attached to a sizable cargo. The addition of extra wild-type coat proteins leads to statistical distribution of coat proteins within the assembly and places this strategy somewhere between the statistical and directed methods.

While statistical encapsulation is straightforward and does not require reengineering of the capsid, it is wasteful and imprecise, as the majority of cargo is not encapsulated. In addition statistical encapsulation is limited to VLP systems that are readily reversibly assembled in vitro. CCMV is part of a rather limited subset of cages that lend themselves to this strategy. While numerous other VLPs can be assembled in vitro the process inevitably leads to significant loss. Directed encapsulation approaches allow for the specific tagging of a cargo such that it can interact with the VLP coat and be recruited for encapsulation (Fig. 8B). If the cargo is readily available during assembly of the VLP, the cargo loading should be limited only by the amount of space available in the VLP leading to the formation a population of regular particles. While directed encapsulation requires engineering of the VLP, the cargo (or both) the resultant system is much more efficient and much higher loading densities can be achieved.

Covalent directed encapsulation has been successfully pursued with the HBV VLP where Staphylococcus aureus nuclease was encapsulated by fusing the entire 17 kDa protein to the C-terminus of the HBV core protein (Beterams et al., 2000). While appealing in its simplicity, this strategy has the same problem as with coiled-coil association of cargo with the CP of CCMV. Steric limitations because of cargo size will eventually prevent assembly of the cage. Methods that employ noncovalent interactions between cargo and capsid allow for more flexibility in the assembly process and the potential for larger cargos (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Encapsulation of genetic cargo within a VLP can be pursued using synthetic or genetic means. Direct genetic fusion of a cargo to the primary coat protein of the VLP can lead to successful encapsulation but has been shown to interrupt the assembly of the VLP. Bioconjugate approaches utilizing small-molecule cross-linkers as a means of attachment (a CLICK linker is shown) can allow for encapsulation either before or after VLP assembly but require either a reversible assembly process or a cargo that is small enough to enter the assembled VLP. Genetic or synthetic fusion of a cargo to a specific encapsulation signal such as a secondary structural protein or a VLP-specific nucleic acid tag allows for recruitment of cargo during VLP assembly. This approach is limited by the availability of such a tag and the ability to incorporate the tagged cargo into the assembly process.

Toward designing-directed noncovalent encapsulation in VLP systems, nature once again provides guidance from BMC systems. In the carboxysome, encapsulation of target enzymes has been shown to depend on a specific domain of the target enzymes that interact with the primary coat protein (Fan et al., 2010). Similar interactions exist in virus assembly pathways. As mentioned previously virus capsids are not inert structural entities but actively interact with their cargo and the surrounding environment. The interior of viruses that assemble around their genome can be positively charged to interact with the genetic cargo, and in some cases the viral coat proteins contain binding sites that recognize specific motifs and structures within the native genome. Other viruses utilize SPs to mediate capsid assembly, which interact with specific sites on the coat protein. These elements of charge, nucleic acid sequence, or structure recognition and scaffold protein binding have all been used for the directed encapsulation of enzymatic cargo within VLPs (Fig. 9).

In a directed in vivo strategy using charge as a means of directing cargo, Hilvert and coworkers genetically modified the coat protein of LS to create a negatively charged interior within the assembled capsid. Assembly of this cage in vivo in the presence of a cargo that had been tagged with a polyarginine tag led to selective encapsulation with retention of the VLP morphology (Seebeck et al., 2006). Because this system is purely genetic the directed interaction between cargo and coat could be exploited as a means to direct evolution of the cage. An HIV protease was tagged for encapsulation within the LS capsid and was coexpressed with a range of coat protein mutants. Increased cell survival was correlated with an increased LS capsid assembly and sequestration and/or inactivation of the protease (Wörsdörfer et al., 2011). Despite the confirmed encapsulation of the protease within the LS, it remains unclear whether the inactivation was due to a more robust capsid assembly or some other interaction between coat and cargo that negatively impacted the protease activity.

Also utilizing nonspecific charge interactions to direct encapsulation Francis and coworkers successfully directed the encapsulation of enzymes in the VLP derived from bacteriophage MS2 using either a DNA-oligomer or a negatively charged peptide tag (Glasgow et al., 2012). A particularly interesting element of this study was the tunable number of cargo molecules in the resultant VLPs achieved through the inclusion of a protein-stabilizing osmolyte during the assembly process.

In the directed encapsulation of cargo, it is desirable to achieve a high degree of specificity. This requires designing where, and in which orientation, an enzymatic cargo is incorporated, not just how it becomes incorporated. A creative strategy has been developed by Finn and coworkers utilizing the natural genome–capsid interactions present in the Qβ VLP platform. The Qβ bacteriophage packages its single-stranded RNA genome through specific interactions between the coat protein interior and a repeated RNA hairpin structure in the genome. To direct encapsulation of an enzymatic cargo in vivo a chimeric single-stranded RNA was developed composed of a hairpin that associates with internal surface of the Qβ CP and an RNA aptamer sequence, developed to bind to an arginine-rich peptide tag (Fiedler et al., 2010). Coexpression of the coat protein gene, RNA aptamer, and a cargo tagged with this arginine-rich peptide leads to linking of the cargo and coat protein through the aptamer and subsequent VLP assembly. Elegantly reusing the genetic sequence, the mRNA transcript for the Qβ CP served as the spacer between the capsid binding hairpin and the cargo binding aptamer. When the mRNA is transcribed, it first serves as the CP transcript and, upon folding, becomes the linker between the cargo and the coat protein. This Qβ/RNA aptamer strategy has been shown to be broadly applicable for the encapsulation of a number of enzyme cargos.

VLPs with multiple structural proteins offer appealing systems for directed encapsulation. In these systems, one of the proteins often serves as the primary structural protein while the other works as a secondary structural element. Through fusion to a secondary structural protein, cargo can be integrated into the natural assembly process. Handa and coworkers successfully utilized the minor coat proteins of SV40 virus as encapsulation mediators (Inoue et al., 2008). The SV40 capsid is composed of a major coat protein (VP1) and two interior minor proteins (VP2 and 3). Fusion of yeast cytosine deaminase to VP2 led to SV40 VLPs with active enzymes on the interior with a controlled packing stoichiometry.

The VLP from bacteriophage P22 has emerged as a versatile platform for in vivo cargo encapsulation by virtue of its size, which offers a large payload volume, readily available secondary structural proteins, a robust assembly pathway and a mechanically robust capsid. The P22 bacteriophage VLP is a T = 7 icosahedral VLP with a diameter of ~60 nm making it larger than most of the spherical VLPs discussed in this review. Assembly of the coat protein is mediated by ~100–300 copies of a disordered interior SP (King et al., 1973). The 303-residue-long SP can be severely truncated to an essential C-terminal scaffolding domain (Parker et al., 1998). Similar to the SV40 encapsulation strategy, this truncated SP can be utilized as an encapsulation tag for protein cargo. By coexpressing a genetic fusion of a protein cargo and the truncated SP together with CP, Douglas and coworkers have successfully encapsulated a wide range of protein and enzyme cargoes (O'Neil et al., 2011).

6.3 Effects of Single-Enzyme Encapsulation

Encapsulation of single enzymes in VLPs has been shown to lead to many beneficial properties from the perspective of making enzymes more applicable as useful and functional catalysts. In some cases the VLP has been shown to enhance the solubility of recombinant proteins that are otherwise localized to inclusion bodies (Patterson et al., 2013a). VLPs have been shown to increase resistance to protease, thermal, and chemical denaturation (Fiedler et al., 2010). Additionally VLP encapsulation provides a means of immobilizing enzyme catalysts to surfaces or materials without directly immobilizing the enzyme, which has been shown to reduce activity in many cases (Rodrigues et al., 2013; Sheldon, 2007).

It is also not unreasonable to anticipate that enzymes encapsulated within the confines of a protein cage might exhibit enhanced kinetics. The structures, dynamics, and mechanisms of intracellular enzymes evolved in highly crowded environments (Ellis, 2001). There is a possibility that restoring elements of that environment will reveal aspects of enzyme behavior that is not evident in the dilute solutions where they are normally studied. Unfortunately single-enzyme encapsulation to date has largely been unfruitful toward enhancing kinetics. In one exception, Cornelissen and coworkers showed enhanced activities for PalB encapsulated in the CCMV VLP in comparison to the free enzyme (Minten et al., 2011). The PalB activity was found to be highest when only a single copy of the enzyme was encapsulated within the CCMV VLP. As the number of PalBs and the encapsulated density increased, activities approached those of free PalB. These findings suggest that it is not the increased density of encapsulation that leads to enhanced PalB catalysis but instead some effects specific to either the CCMV cage or the PalB.

Most cases of single-enzyme encapsulation have shown no change or reduced catalytic turnover upon encapsulation. Encapsulation of yeast cytosine deaminase in SV40 slightly reduced activity, although the kinetic parameters were not examined in detail (Inoue et al., 2008). Finn and coworkers found that encapsulation reduced the activity of peptidase E (PepE) (Fiedler et al., 2010). One of the most dramatic changes in turnover was a sevenfold decrease after encapsulation of thermophilic AdhD in P22 (Patterson et al., 2012).

The solitary example of sizable increase in turnover for a single enzyme has been the encapsulation of heterodimeric Escherichia coli NiFe hydrogenase in the P22 VLP (Fig. 10). Douglas and coworkers demonstrated that coencapsulation of both hydrogenase subunits led to a 100-fold increase in hydrogen production (Jordan et al., 2016). To refer to this system as a single enzyme may be misleading as the heterodimeric nature of the enzyme is likely responsible for the dramatic increase in observed activity. This enzyme exists naturally as two different membrane-bound subunits that associate on the surface of the membrane. Solution studies of the soluble domains of this enzyme have shown that it is unstable and prone to inactivation by oxygen. Additionally the dimer interaction is dynamic in solution (Jordan et al., 2016). When it is studied as a dilute soluble enzyme the hydrogenase is taken completely out of its natural context, perhaps more so than the naturally free soluble enzymes used in many of the other VLP enzyme encapsulation studies. Encapsulation in the P22 SP system leads to high-local concentrations of both subunits, which cannot escape the capsid, and therefore subunit association to form the active heterodimer is favored.

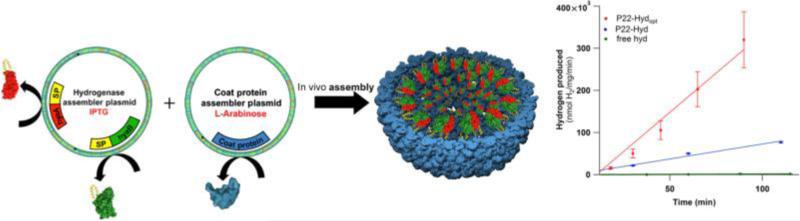

Fig. 10.

Encapsulation of the heterodimeric hydrogenase within the P22 VLP leads to a more than 100× increase in the turnover of the enzyme. At left a schematic of gene production in this system showing production of the two-hydrogenase subunits (red and green) as fusions to the P22 scaffold (SP yellow) and subsequent expression of the P22 coat (CP blue) allowing for folding and maturation of the cargo before encapsulation. This strategy protects and enhances the cargo as evidenced by the increase in hydrogen production shown in the reaction plot at right where the optimized encapsulated sample (red) drastically out performs the free enzyme (green) and an unoptimized encapsulated construct (blue). Figure adapted from Jordan, P.C., et al., 2016. Self-assembling biomolecular catalysts for hydrogen production. Nat. Chem. 8, 179–185.

One drawback of assessing the kinetics of these VLP systems, and enzymes in general, purely based on turnover is that turnover can be drastically changed if the percentage of the enzymes in the assay that are actually active changes. This subtly is particularly evident in the case of the hydrogenase (Hyd-1) encapsulated in P22 where both the turnover and the number of intact active sites were directly measured. Upon encapsulation the turnover and the number of intact active sites both increased suggesting that the increase in turnover is partially due to an increased percentage of enzymes that are active (Jordan et al., 2016). An increase in turnover is advantageous for using enzymes as functional catalysts regardless of the origins of that increase. Mechanistically, however, it is of interest to distinguish between kinetic changes that originate from increasing the percentage of active enzyme in the population vs changes in the conformation or environment of each enzyme that may also change the kinetic behavior.

Changes in the apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for an encapsulated enzyme system are independent of the concentration and provide some insight into kinetic effects that may arise from the high-density-encapsulated environment. values have been reported for several of the enzyme systems discussed earlier. Encapsulation of luciferase inside Qβ showed large changes in for ATP and luciferin, with nearly a 10- and 20-fold increase, respectively, for the most crowded constructs, and showed a positive correlation with increasing number of encapsulated enzymes (Fiedler et al., 2010). Alternatively, encapsulation of the enzyme PepE in Qβ showed no change in with a twofold lower turnover. Encapsulation of AdhD in P22 exhibited decreased values for acetoin in the encapsulated form despite lower turnover (Patterson et al., 2012). Changes in of the NADH cofactor utilized by AdhD showed an apparent increase of two- to threefold upon encapsulation, although these differences were barely resolvable statistically.

These examples show that significant differences arise from VLP encapsulation in an enzyme and potentially cage-dependent manner. Crowding studies, utilizing crowding agents to enforce crowded environments, have reported variable kinetic changes, both increases and decreases in Km, and turnover values. In solution, crowding studies have the advantage of being able to more easily utilize techniques, such as circular dichroism, to monitor changes in enzyme structure in the crowded environment (Eggers and Valentine, 2001; Jiang and Guo, 2007; Sasahara et al., 2003; Tokuriki et al., 2004). The acquisition of structural information is essential in crowding studies in order make conclusive connections regarding the relationship between enzyme crowding and kinetics. Monitoring the structure of enzymes in a VLP-encapsulated environment is challenging due to the large background signal from the cage proteins. Techniques such as Föster resonance energy transfer have been used in VLP-encapsulated systems to measure the degree of crowding but have not to our knowledge been applied to encapsulated enzyme systems (O'Neil et al., 2012). Additionally cyro-electron microscopy reconstructions and mechanical studies utilizing AFM may be able to provide connections between structural changes and kinetic effects.