ABSTRACT

Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), based on the recognition of IgG-opsonized targets by the low-affinity receptor for IgG FcγRIIIA/CD16, represents one of the main mechanisms by which therapeutic antibodies (mAbs) mediate their antitumor effects. Besides ADCC, CD16 ligation also results in cytokine production, in particular, NK-derived IFNγ is endowed with a well-recognized role in the shaping of adaptive immune responses.

Obinutuzumab is a glycoengineered anti-CD20 mAb with a modified crystallizable fragment (Fc) domain designed to increase the affinity for CD16 and consequently the killing of mAb-opsonized targets. However, the impact of CD16 ligation in optimized affinity conditions on NK functional program is not completely understood.

Herein, we demonstrate that the interaction of NK cells with obinutuzumab-opsonized cells results in enhanced IFNγ production as compared with parental non-glycoengineered mAb or the reference molecule rituximab. We observed that affinity ligation conditions strictly correlate with the ability to induce CD16 down-modulation and lysosomal targeting of receptor-associated signaling elements. Indeed, a preferential degradation of FcεRIγ chain and Syk kinase was observed upon obinutuzumab stimulation independently from CD16-V158F polymorphism. Although the downregulation of FcεRIγ/Syk module leads to the impairment of cytotoxic function induced by NKp46 and NKp30 receptors, obinutuzumab-experienced cells exhibit an increased ability to produce IFNγ in response to different stimuli.

These data highlight a relationship between CD16 aggregation conditions and the ability to promote a degradative pathway of CD16-coupled signaling elements associated to the shift of NK functional program.

KEYWORDS: ADCC, Fc glycoengineering, FcγRIIIA/CD16, IFNγ, NK cells, obinutuzumab

Introduction

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have revolutionized the treatment of many types of cancer. In particular, rituximab anti-CD20 mAb-based chemoimmunotherapy regimens have represented a breakthrough in the treatment of several B cell malignancies, and now constitute the front-line therapy for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas.1 Rituximab also stands as the reference molecule for the comparison with new generation anti-CD20 mAbs, designed to overcome rituximab refractoriness and to reach greater clinical efficacy.2 Among them, obinutuzumab is now approaching the clinical use as a first line therapy for previously untreated CLL and for rituximab-refractory indolent lymphomas.3,4 Obinutuzumab is a third-generation, type II, humanized IgG1κ mAb that binds to a CD20 epitope in a different space orientation and with a wider elbow-hinge angle compared with rituximab.5 Obinutuzumab was glycoengineered by removing core fucose in the crystallizable fragment (Fc) portion of the mAb. This modification substantially enhances the binding affinity to FcγRIIIA/CD16, thus improving antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)6,7 and antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP).8,9 As a type II antibody, obinutuzumab antitumor effects mostly rely on ADCC and direct cytotoxic effects; in contrast, type I mAbs (rituximab and ofatumumab) display stronger complement-dependent cytotoxicity and minimal direct cytotoxicity.9-11

The relative contribution of ADCC and ADCP to the antitumor activity of anti-CD20 antibodies has been addressed by several groups. In murine models, different studies report a primary role for phagocytic mechanisms in antitumor activity induced by both class I and class II anti-CD20 mAbs.12-14 However, others have demonstrated the importance of mAb-mediated NK cell activation especially in long-term antitumor protection, suggesting that the mechanism of action may vary depending on the tumor model and location.15,16

CD16 is expressed on various immune effector cells, namely macrophages, monocytes and natural killer (NK) cells.17 The impact of a FCGR3A polymorphism in predicting the clinical response to rituximab treatment in patients with Follicular Lymphoma highlights the relevance of such receptor in antitumor activity.18,19 Specifically, the relevant genetic variant of FCGR3A gene consists of a polymorphism present on aminoacid position 158 (c.559G>T, p.Phe158Val) predicting a lower affinity form with a phenylalanine (FcγRIIIA-158F) or a higher affinity form with a valine (FcγRIIIA-158V).20 In vitro evidence demonstrated that Fc glycoengineering confers the ability to achieve higher ADCC even in individuals harboring the low-affinity CD16 allotype (FcγRIIIA-158F), thus overcoming the problem of individual heterogeneity in FCGR3A polymorphisms and therapy responses.21,22 Moreover, multiple lines of evidence have shown the inhibitory killer cell immunoglobulin like receptor (KIR)/HLA interactions do not negatively impact on obinutuzumab-mediated target cell depletion.21

CD16 represents the prototype of NK activating receptors; its engagement by IgG-opsonized targets is sufficient to trigger ADCC as well as the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as IFNγ, TNF, IL-6, GM-CSF and CCL5).23,24 Among them, IFNγ stands as a well-recognized key immunoregulatory factor in the shaping of antitumor adaptive immune responses by modulating the responses of dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells.25-27

In human NK cells, CD16 exhibits two extracellular Ig domains, a short cytoplasmic tail and a trans-membrane domain that enables its association with immune-receptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-containing CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains,28 which guarantee Syk- and ZAP-70-dependent signal transduction.24 Notably, CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains are also associated with the natural cytotoxicity receptors (NCRs), such as NKp46 and NKp30.29 Together with NCRs, other natural activating receptors including the lectin-like receptor NKG2D, the signaling lymphocyte-activation molecule (SLAM) family member 2B4, the Ig-like receptor DNAM-1 participate to the recognition of a multitude of ligands expressed on infected and tumor cells, playing an important role in antitumor response and immune-surveillance.24

In a recent study, we demonstrated that following CD16 stimulation by rituximab-opsonized targets, hence under low-affinity conditions, NK cells became unable to further kill target cells either via antibody-dependent or natural cytotoxicity.30

In this study, we have compared the impact of exposure of primary NK cells to rituximab or obinutuzumab, in both its glycoengineered and non-glycoengineered wild type (wt) form, on NK cell functions and responsiveness.

Using an in vitro setting, we observed that obinutuzumab, by virtue of its increased affinity for CD16, besides increasing ADCC also induces a significant enhancement of IFNγ production. Notably, the affinity ligation conditions strictly correlate with the ability to induce CD16 down-modulation and lysosomal targeting of receptor-associated signaling elements. Indeed, a preferential degradation of FcεRIγ chain and Syk kinase is observed upon obinutuzumab stimulation independently from CD16-V158F polymorphism. Although the downregulation of FcεRIγ/Syk module leads to the impairment of cytotoxic function induced by NKp46 and NKp30 receptors, the ability of obinutuzumab-experienced cells to produce IFNγ in response to cytokines, target stimulation as well as obinutuzumab-mediated CD16 re-stimulation, is enhanced.

Overall, our data indicate that CD16 aggregation conditions may dictate both the amplitude of NK responsiveness and the ability to shift NK functional program.

Results

CD16 engagement by obinutuzumab-opsonized targets results in enhanced cytotoxicity and IFNγ production in primary human NK cells

Although the enhancement of NK cell-mediated ADCC toward obinutuzumab-coated targets is well described,6,11,21 the impact of mAb defucosylation on the ability to induce NK-derived IFNγ production has not been explored yet.

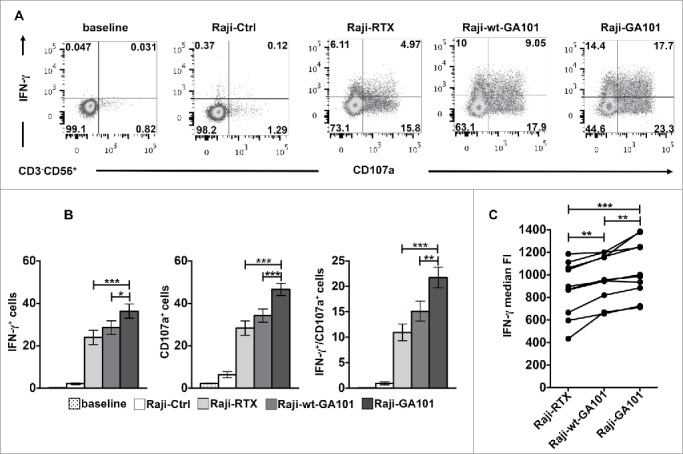

To analyze at what extent individual NK cells can be induced to perform degranulation and/or cytokine production, the intracellular expression of IFNγ and surface expression of CD107a (marker of lytic granule exocytosis) were simultaneously assessed on peripheral blood CD3−CD56+ NK cells by multicolour cytofluorimetric analysis. Hereafter, in all our experimental settings, we obtained the stimulation of CD16 by co-culturing NK cells with CD20+ B cell lymphoma Raji cells that were opsonized with rituximab or obinutuzumab, in the defucosylated (GA101) or wild type version (wt-GA101), at saturating concentration as detailed in Materials and methods section and Fig. S1. Being Raji cells almost completely resistant to freshly isolated NK-mediated killing, the stimulation with non-opsonized Raji does not induce significant IFNγ production or CD107a expression (Fig. 1A and B). The stimulation of NK cells with rituximab-opsonized targets induces both degranulation and IFNγ production with a slightly greater frequency of CD107a+ than of IFNγ+ cells, confirming the hierarchy among NK cell responses described previously.31 Under such stimulation conditions, only 11% of the cells on average were able to perform both responses. Notably, when NK cells were stimulated with obinutuzumab-opsonized targets both degranulation and IFNγ production appeared significantly enhanced with respect to rituximab. Importantly, the percentage of NK cells that acquired the ability to degranulate and to produce IFNγ results almost twice in response to obinutuzumab than to rituximab. The enhanced activity of obinutuzumab is for large part attributable to defucosylation, in fact, wt-GA101 behaves similarly to rituximab in inducing NK functions. Besides the increased portion of IFNγ producing cells, the analysis of median values demonstrates that obinutuzumab stimulation increases the IFNγ quantity on a per cell basis (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

CD16 engagement by obinutuzumab-opsonized targets enhances both CD107a mobilization and IFNγ production. PBMCs were left alone (baseline) or combined (2:1) with rituximab (Raji-RTX)-, obinutuzumab (Raji-GA101)-, wt-GA101 (Raji-wt-GA101)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Raji-Ctrl) for 6 h. The percentage of IFNγ+ and CD107a+ cells among NK cells (CD3−CD56+) were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Plots from one representative donor are shown. (B) Data (mean ± SEM) from nine donors are shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001. Compared to baseline or Raji-Ctrl samples, all the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.0001). (C) The median fluorescence intensity (FI) values of IFNγ NK cells from nine individuals are reported in the graph. Each line represents a single donor. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001.

On the same line, when we assessed the ability of primary cultured NK cells to kill anti-CD20-opsonized targets or to produce IFNγ, we observed higher responses in cells stimulated with obinutuzumab with respect to rituximab (Fig. S2). Together these data demonstrate that, by virtue of defucosylation, obinutuzumab induces a comprehensive improvement of NK cell responses also inducing multiple effector responses in individual cells.

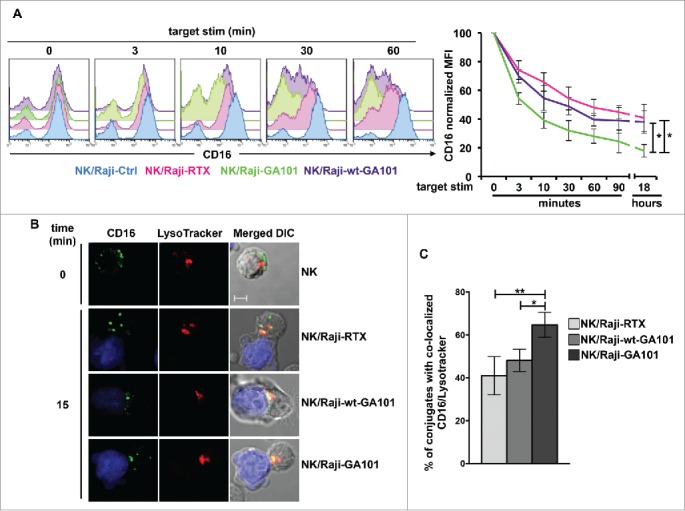

CD16 engagement by obinutuzumab-opsonized targets promotes an enhanced receptor down-modulation and lysosomal targeting

We recently described the down-modulation of CD16 receptor complex upon its engagement by rituximab-opsonized targets.30 To compare the kinetics of CD16 down-modulation induced by rituximab or obinutuzumab,we evaluated CD16 levels in the course of the interaction with anti-CD20-opsonized targets. Surface CD16 levels were assessed by staining with B73.1 mAb whose binding to CD16 is not affected by Fc masking.32 For each time of stimulation, we kept as 100% CD16 levels of sample stimulated with non-opsonized targets. Our data (Fig. 2A) show a progressive and marked CD16 down-modulation in NK cells interacting with anti-CD20-opsonized targets (Fig. 2A, right panel). Notably, the stimulation with obinutuzumab promotes a more rapid and profound CD16 down-modulation, reaching almost 17% of initial levels (vs 40% in rituximab-stimulated cells). In wt-GA101-stimulated cells, the kinetics of CD16 downregulation appears slower and overall less efficient, evidencing the role of the increased CD16 affinity binding. We also addressed the persistence of CD16 down-modulated status by monitoring its expression levels in NK cells that were immunomagnetically isolated upon 18 h co-cultures with anti-CD20-opsonized targets (hereafter “experienced cells”) and maintained in culture for different lengths of time. Under such conditions, we observed a progressive recovery of CD16 expression that was complete after 48 h of culture (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

CD16 engagement by anti-CD20-opsonized targets induces receptor down-modulation and lysosomal targeting. (A) Primary cultured NK cells were combined (2:1) for the indicated times with rituximab (Raji-RTX)-, obinutuzumab (Raji-GA101)-, wt-GA101 (Raji-wt-GA101)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Raji-Ctrl). CD16 surface expression was evaluated by FACS analysis by anti-CD16 (Leu11c) mAb gating on CD56+ population. (Left panels) The overlays of histograms from one representative experiment are shown. (Right panel) Normalized CD16 MFI was calculated as follows: (MFI of the stimulated sample/MFI of Ctrl sample) × 100, assuming as 100% the MFI value of NK cells co-cultured with non-opsonized (Raji-Ctrl) targets for each time of stimulation. Data (mean ± SEM) from six independent experiments are shown. *p < 0.05. (B) LysoTracker-labeled NK cells (red) were combined (2:1) for 15 min with CMAC-labeled rituximab (NK/Raji-RTX)-, obinutuzumab (NK/Raji-GA101)- or wt-GA101 (NK/Raji-wt-GA101)-opsonized targets (blue). Cell conjugates were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-CD16 (B73.1) followed by Alexa Fluor 488-GAM (green) Abs. A representative image of NK/target conjugate and isolated NK cell are shown. The overlay of the three-color merged image and the differential interference contrast (DIC) is shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) The percentage of conjugates containing CD16/lysosome co-localization (Pearson's correlation coefficient > 0.2) was analyzed on randomly acquired fields of three independent experiments (mean ± SEM; n = 50 conjugates). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Then, we evaluated the fate of internalized CD16 by studying its re-distribution in lysosomal compartment by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Primary cultured NK cells were allowed to interact with anti-CD20-opsonized targets for 15 min, and LysoTracker was used to visualize lysosomes. As compared with the ring pattern observed in unstimulated cells, CD16 distributed in intracellular dots in cells interacting with rituximab- or obinutuzumab-opsonized targets (Fig. 2B). The analysis of 50 E/T conjugates in randomly acquired fields reveals that a substantial portion of internalized CD16 co-localizes with lysosomes. Interestingly, we observed that the percentage of cells with CD16/lysosome co-localization was significantly higher in NK cells conjugated to obinutuzumab-opsonized cells with respect to those interacting with rituximab- or wt-GA101-opsonized targets (Fig. 2C).

This data demonstrate that obinutuzumab, by virtue of defucosylation, promotes an increased rate of CD16 down-modulation associated with an enhanced lysosomal targeting.

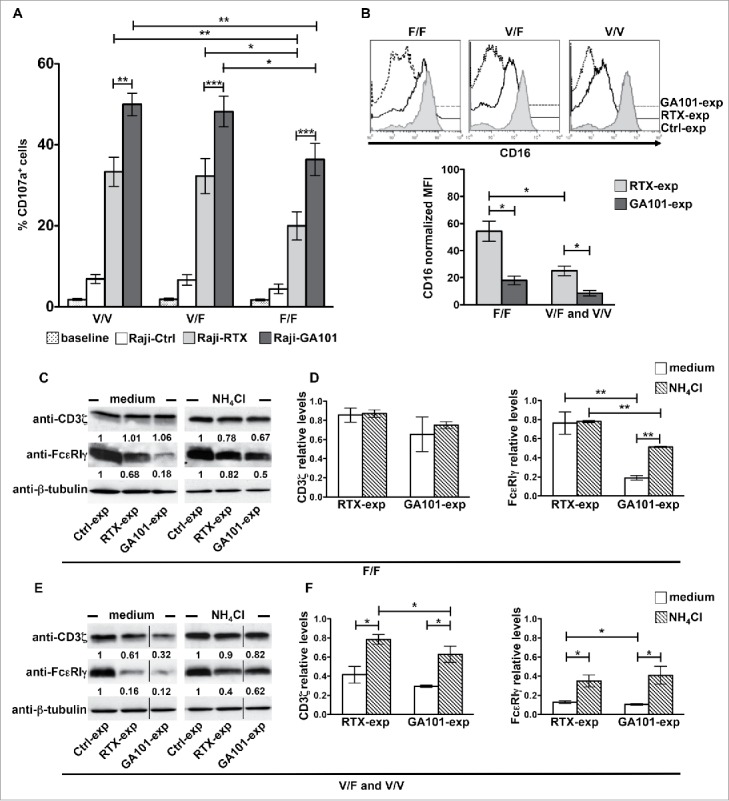

Preferential occurrence of FcεRIγ degradation upon obinutuzumab-coated target interaction: Impact of FCGR3A-V158F polymorphism

We sought to analyze whether the FCGR3A c.559G>T polymorphism would impact on CD16 dynamics. V158F single nucleotide polymorphism was determined by cytofluorimetric approaches33 and confirmed by a PCR-based analysis.34,35 Of the 125 typed donors, 21 and 34 were V/V and F/F homozygous, respectively, while 70 were V/F heterozygous, testifying a large prevalence of individuals at intermediate–high affinity. In line with previous observations demonstrating that obinutuzumab triggers an enhanced ADCC irrespective of CD16 allotype,21,22 we observed that in F/F individuals surface CD107a levels in response to obinutuzumab were significantly higher with respect to rituximab, although lower than V/F or V/V donors (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

CD16 engagement by obinutuzumab-opsonized targets results in enhanced degranulation as well as FcεRIγ lysosomal degradation irrespective of FCGR3A-V158F polymorphism. (A) PBMCs were left alone (baseline) or allowed to interact (2:1) with rituximab (Raji-RTX)-, obinutuzumab (Raji-GA101)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Raji-Ctrl) for 6 h. The percentage of CD107a+ cells among CD3−CD56+ was evaluated by FACS analysis in individuals grouped by FCGR3A genotype (high-affinity allele V, low-affinity F; V/V, n = 6; V/F, n = 6; F/F, n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. For each group, compared with baseline or Raji-Ctrl samples, all the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). (B–F) Primary cultured NK cells (n = 5/genotype) were isolated upon 18 h co-culture (2:1) with biotinylated rituximab (RTX-exp)-, obinutuzumab (GA101-exp)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Ctrl-exp) in the presence of medium alone (medium) or, when indicated, with 20 mM NH4Cl. (B) CD16 surface expression was evaluated by FACS analysis by anti-CD16 (Leu11c) mAb in individuals grouped by FCGR3A genotype. (Top) Histogram overlay of one representative donor/genotype .is shown and (bottom) normalized CD16 MFI calculated as described in Fig. 2A are depicted in bar graph (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05. (C, E) An equal amount of proteins from whole cell lysates was immunoblotted as indicated. The same membrane was immunoblotted with anti-FcεRIγ and, after stripping, with anti-CD3ζ Abs followed by anti-β-tubulin for sample normalization. Membranes containing untreated- (medium) or NH4Cl-treated samples were developed in the same film. The black vertical lines indicate that intervening lanes were sliced out. The numbers represent the relative protein amount of the indicated proteins obtained by normalizing to the level of β-tubulin and expressed as fold change respect to Ctrl-exp samples (arbitrarily set to 1). One representative experiment is shown. (D, F) The relative values (mean ± SEM) of CD3ζ or FcεRIγ chains from five independent experiments are depicted in bar graphs.*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

We then compared the ability of rituximab and obinutuzumab to modulate CD16 levels among different allotypes. Upon a sustained receptor stimulation (18 h) we observed that rituximab-induced CD16 down-modulation is less efficient in F/F donors than in V/F and V/V donors, which behave similarly. By contrast, when we stimulated NK cells with obinutuzumab-opsonized targets, receptor downregulation was stronger and not significantly affected by CD16 allotype (Fig. 3B).

CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains associate to CD16 receptor in NK cells as homo or heterodimers, being γ/γ homodimers the predominant species.28 The biochemical analysis of CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains in anti-CD20-experienced NK cells reveals that obinutuzumab, but not rituximab, promotes a marked and selective reduction of FcεRIγ chain levels in F/F donors, being CD3ζ only marginally affected (Fig. 3C and D). Differently, both obinutuzumab and rituximab induce FcεRIγ and, at a lower degree, CD3ζ downregulation in V/F or V/V donors (Fig. 3E and F). The reduction of FcεRIγ and CD3ζ is, at least for a consistent part, attributable to lysosomal degradation as the treatment with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), which inhibits lysosome functions, in part prevents such response (Fig. 3C–F).

Focusing our analysis on V/F and V/V donors in which both FcεRIγ and CD3ζ undergo degradation, we observed that the degradative pathway involves other CD16-activated signaling elements since Syk, but not ZAP-70, kinase levels are significantly reduced in anti-CD20-experienced NK cells (Fig. S4A). Since we previously demonstrated the contribution of the ubiquitin pathway in Syk degradation induced by anti-CD16-triggered receptor engagement,36 we investigated whether Syk undergoes ubiquitin modification in response to anti-CD20 mAb stimulation. NK cells were stimulated with fixed anti-CD20-opsonized targets and tyrosine phosphorylated and ubiquitinated Syk levels were analyzed in Syk immunoprecipitates. In such experiments, we introduced, as a further negative control, the obinutuzumab Fab fragment as an antibody that lacks the ability to bind to CD16. Receptor engagement rapidly induces a typical pattern of Syk tyrosine phosphorylation that appears as multiple molecular species showing a regular molecular weight increase suggestive of ubiquitination. Indeed, immunoblotting with anti-ubiquitin mAb visualizes multiple bands in the region of phosphorylated Syk. Notably, Syk ubiquitination signal appears more persistent and stronger in obinutuzumab- than in rituximab-stimulated samples (Fig. S4B).

Overall, the data demonstrate that in CD16 intermediate/high affinity donors both antibodies behave similarly in inducing the degradation of FcεRIγ, and to a lesser extent of CD3ζ and of Syk kinase, whereas, only obinutuzumab stimulation activates a degradative pathway selectively involving FcεRIγ, in low-affinity donors.

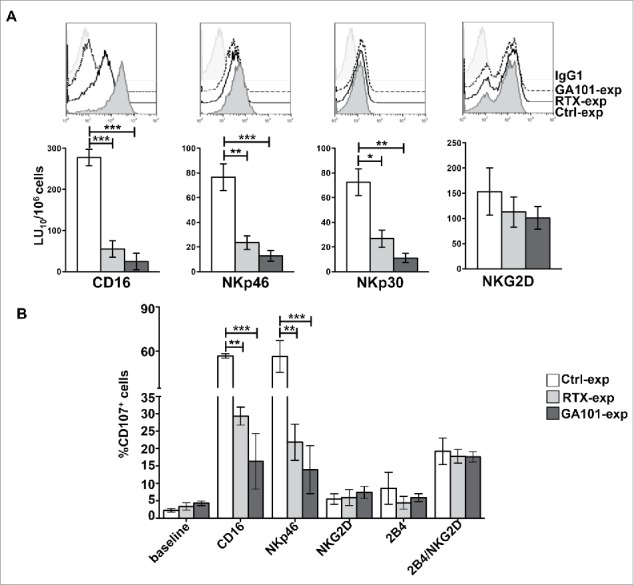

NK cell interaction with anti-CD20-opsonized targets results in the impairment of NKp46- and NKp30-dependent cytotoxic response

We then investigated the functional outcome of the sustained CD16 ligation to mimic the chronic NK stimulation occurring in mAb-treated patients. In particular, we addressed whether the internalization of CD16 receptor complex leading to reduced levels of FcεRIγ, CD3ζ and Syk kinase would impact on NK cytolytic potential.

NK cells were co-cultured for 18 h with anti-CD20-opsonized targets. Cytotoxic activity of experienced cells was assessed against FcR+ P815 target cells in a redirected killing assay in the presence of anti-CD16, anti-NKp46, anti-NKp30 or anti-NKG2D mAbs to explore the killing ability induced by ITAM-dependent- or ITAM-independent receptors. We also excluded that, by this time, residual anti-CD20 could be detected on the surface of NK cells (not shown). As expected, because of the reduction of CD16 expression levels, mAb experienced NK cells exhibited a marked reduction of CD16-dependent killing (reverse ADCC) (Fig. 4A). Moreover, being CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains the molecular adaptors required for NKp46 and NKp30 signal transduction,29 we also observed a significant impairment of NKp46 and NKp30 cytotoxic response, both in rituximab- and obinutuzumab-experienced NK cells (Fig. 4A). We also noted a slight reduction of NKp46 expression levels in anti-CD20-experienced cells. On the opposite, NKG2D-dependent killing, relying on DAP10 adaptor,24 appeared more preserved.

Figure 4.

CD16 engagement by anti-CD20-opsonized targets results in the impairment of FcεRIγ- and CD3ζ-dependent NKp46- and NKp30-mediated killing. (A) Primary cultured NK cells from V/F and V/V individuals (n = 5) were isolated upon 18 h co-culture (2:1) with biotinylated rituximab (RTX-exp)-, obinutuzumab (GA101-exp)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Ctrl-exp). Cells were stained as indicated for FACS analysis and tested in 51Cr-release redirected killing assays toward P815 FcR+ cells in presence of Abs for the indicated receptors. (Top) The overlays of histograms from one representative experiment of five performed are shown. (Bottom) Lytic units (LU) from five independent experiments are shown. Bar graphs depict mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005. (B) NK cells as in A were stimulated for 4 h with the indicated plastic-immobilized mAbs. The percentage of CD107a+ cells was evaluated by FACS analysis gating on CD56+ cells. Data (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments are shown. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We also analyzed CD107a levels induced by stimulation with plastic-immobilized mAbs specific for different activating receptors. Also, in this setting, we observed a significant defect of degranulation after stimulation of CD16 or NKp46 (Fig. 4B). No differences with respect to the control population were observed following stimulation of NKG2D and 2B4, all CD3ζ- and FcεRIγ-independent activating receptors, which are able to induce degranulation only when stimulated in paired combinations.37

In line with the lack of CD16 adaptor degradation in response to rituximab (Fig. 3C), we observed that in F/F donors NKp46- and NKp30-dependent killing was more preserved in rituximab- with respect to obinutuzumuab-experienced cells (Fig. S5).

Obinutuzumab-experienced NK cells exhibit an enhanced IFNγ production

It is well known that cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity can be uncoupled in target-stimulated NK cells.38 Since the loss of FcεRIγ/Syk module has been associated to an increased IFNγ producing potential,39 we explored the ability of anti-CD20-experienced NK cells to secrete IFNγ.

As shown in Fig. 2A, CD16 levels were markedly down-modulated in the course of interaction with anti-CD20-opsonized targets. To obtain, albeit at partial levels, the re-expression of CD16, we cultured NK cells for 12 h after target detachment. Because of the stronger CD16 downregulation induced by obinutuzumab, the recovery of CD16 expression was significantly lower in obinutuzumab-experienced NK cells (Fig. 5A).

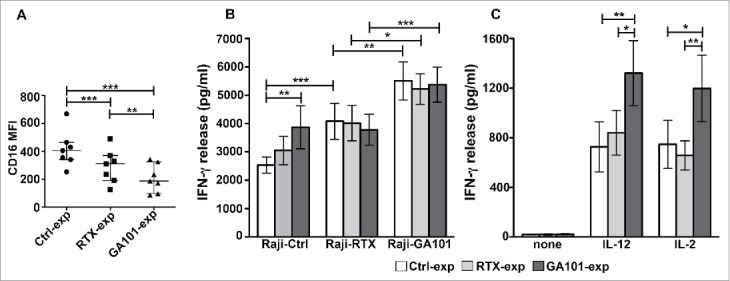

Figure 5.

Obinutuzumab-experienced NK cells exhibit an enhanced IFNγ production in response to cytokines, targets or obinutuzumab re-stimulation. Primary cultured NK cells were isolated upon 90 min of co-culture (2:1) with biotinylated rituximab (RTX-exp)-, obinutuzumab (GA101-exp)-opsonized or non-opsonized Raji (Ctrl-exp) and re-plated for 12 h. (A) NK cells were stained with anti-CD16 (Leu11c) mAb for FACS analysis. Graph depicts CD16 MFI and data are presented as median with the interquartile range. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0005. (B) NK cells were re-stimulated (2:1) with non-opsonized targets (Raji-Ctrl), rituximab-opsonized (Raji-RTX) or obinutuzumab-opsonized (Raji-GA101) target cells in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/mL), or (C) left untreated (none) or treated with IL-12 (10 ng/mL) or IL-2 (100 U/mL). After 18 h, supernatants were collected and assessed for IFNγ levels. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of seven independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.0001. Compared to untreated (none), all the differences were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.001).

NK cells were then stimulated for 18 h with non-opsonized targets, anti-CD20-opsonized targets, IL-12 or IL-2. Exploring the responsiveness of experienced cells, that we assessed in the presence of IL-12, we noted that the stimulation with non-opsonized Raji (Raji-Ctrl) enhances IFNγ production in obinutuzumab (3868.7 pg/mL ± SEM)- but not in rituximab (3050.8 pg/mL ± SEM)-experienced cells, with respect to control (2572.25 pg/mL ± SEM) population, indicating that obinutuzumab experienced cells are more prone to produce the cytokine in response to the stimulation of receptors engaged by ligands expressed by Raji cells (Fig. 5B).40 As reported in Fig. 1A and B, the stimulation with Raji alone does stimulate NK cells (not shown).

Regarding the responsiveness to CD16 re-stimulation, we noted that while mAb-experienced cells failed to respond to rituximab re-stimulation, they significantly respond to obinutuzumab re-stimulation (Fig. 5B). Such enhanced response to obinutuzumab was largely independent from CD16 levels (Fig. 5A).

Further, in obinutuzumab-experienced cells, the ability to produce IFNγ in response to IL-12 or IL-2 stimulation is significantly higher respect to control and rituximab-experienced populations (Fig. 5C). Such responses were observed across CD16 genotypes (not shown).

Together these data demonstrate that NK cells that have encountered obinutuzumab-opsonized targets exhibit a superior responsiveness to target and cytokine stimulation. Moreover, anti-CD20-experienced cells are able to produce IFNγ only in response to a subsequent obinutuzumab, but not rituximab, stimulation.

Discussion

Among the Fc-optimized antitumor mAbs, obinutuzumab is the first glycongineered anti-CD20 mAb approved for clinical use.3,5 The defucosylation of its Fc portion results in the enhanced affinity for CD16 and the consequent increased ability to activate NK cells. Surprisingly, although several preclinical studies showed that obinutuzumab is more potent in inducing NK cell-mediated tumor target cell killing as compared with the reference mAb, rituximab,6,7,22 no studies addressed its ability to induce cytokine production by NK cells.

Here, by the simultaneous monitoring of IFNγ and CD107a in individual cells, we assessed the relationship between cytokine production and degranulation induced by the interaction with obinutuzumab- or rituximab-opsonized targets. We show that obinutuzumab, used at 10 times lower concentration than rituximab, stimulates primary NK cells to produce IFNγ more effectively than rituximab, increasing both the proportion of cells producing IFNγ (Fig. 1A and B) and the amount of IFNγ on a per cell basis (Fig. 1C). Moreover, as expected, obinutuzumab was superior to rituximab in the ability to stimulate degranulation. The enhanced functional activation is conferred by glycoengineering since the wt mAb promotes significantly lower IFNγ production (Fig. 1A and B). The observation that wt-GA101 is itself able to induce an increased amount of IFNγ with respect to rituximab indicates that the increased efficacy of obinutuzumab is not exclusively explained by differences in Fc portion but also by other characteristics that can affect CD16 aggregation, such as the lack of the ability to induce CD20 internalization in obinutuzumab-coated targets.5,22 Classically, the interaction of NK cells with opsonized targets leads to the activation of the full NK functional program, i.e., cytotoxicity and cytokine production, with an higher activation threshold (strength and duration of stimuli) required for cytokine secretion when compared with cytotoxicity.24,31 In line with this notion, we found that the fraction of NK cells that became cytolytic (as judged by degranulation) following rituximab or obinutuzumab stimulation, is higher than the fraction of NK cells that produces IFNγ under the same conditions. Interestingly, in obinutuzumab-stimulated cells, we observed that the frequency of NK cells performing both degranulation and IFNγ production is proportionally higher (Fig. 1B), indicating that the increased affinity binding enables more cells to reach the signaling threshold required for IFNγ production. Such observations may shed new light on the cytokine release syndrome reported in obinutuzumab-treated patients41 where a huge amount of circulating IFNγ levels was reported.

In vivo activation of NK cells in rituximab-receiving patients correlates with the down-modulation of CD16 levels.42,43 Such response is influenced by the affinity ligation conditions, as it has not been observed in F/F subjects.43,44

Several groups, including ours, have shown that CD16 down-modulation induced by interaction with rituximab-opsonized targets may depend on receptor shedding45 and/or internalization,30 with the relative contribution of each mechanism depending on the engagement conditions (for instance immobilized versus soluble mAb). Here, we observed that when CD16 was engaged by obinutuzumab-opsonized targets, its down-modulation appears more profound and faster with respect to rituximab, leaving a 17% of residual surface CD16 levels (vs 40% upon rituximab stimulation) (Fig. 2A).

It has been clearly demonstrated that glycoengineered obinutuzumab exhibits higher affinity for CD16 irrespectively of CD16 allotype.7,22 Indeed, obinutuzumab binds to CD16 variants with an affinity that is higher than that of rituximab for the high-affinity receptor isoform.7 Accordingly, we observed that CD16 down-modulation in response to obinutuzumab-opsonized targets is significantly higher across all CD16 allotypes, with respect to rituximab (Fig. 3B). This trend strictly correlates with the induction of degranulation (Fig. 3A), remarking the link between affinity ligation conditions, receptor down-modulation and functional responses.

The observation of the capability of obinutuzumab to induce a more efficient decrease of surface CD16 levels is not conflicting with the increased mAb-dependent responses; in fact, the ability of internalized NK receptors to transmit activating signals from intracellular compartments before their lysosomal targeting has been recently reported by our group.46 Indeed, we observed that, upon 15 min of stimulation, a consistent portion of internalized receptor appears delivered to the lysosomal compartment (Fig. 2B and C). The possibility that internalized CD16 may convey mAb-targeted CD20 into lysosome through trogocytosis47 requires further investigation. A main finding in our work is the observation that the interaction with anti-CD20-opsonized targets promotes the preferential lysosomal degradation of CD16-associated signaling elements, with affinity ligation conditions dictating the strength and the quality of the response.

We observed that the levels of FcεRIγ dramatically fall in response to obinutuzumab irrespective from CD16 allotype (Fig. 3C and E), whereas rituximab stimulation is followed by FcεRIγ degradation only in intermediate/high affinity donors. One likely explanation about the preferential degradation of FcεRIγ with respect to CD3ζ chain is the relative abundance of γ/γ homodimers respect to γ/ζ heterodimers or ζ/ζ homodimers associated to CD16 in human NK cells.28

Ligation-dependent FcεRIγ and CD3ζ phosphorylation permits the ITAM-dependent recruitment and activation of Syk and ZAP-70 tyrosine kinases that subsequently undergo, together with the engaged receptor complex, to ubiquitin-dependent degradation.36 Here, we report that the interaction with anti-CD20-coated targets is followed by the selective degradation of Syk but not ZAP-70 kinase, attributable to the activation of ubiquitin-dependent pathway. The identification of the ligase responsible for Syk ubiquitination requires further investigation.

Interestingly, the downregulation of FcεRIγ and Syk, both myeloid cell related signaling proteins, is the hallmark of the recently described memory-like or adaptive NK cells.39,48 Such NK cell subset, endowed with a specific epigenetic signature, has been expanded in vitro by the antibody-mediated recognition of viral antigens, proving that CD16-driven responses may contribute to calibrate NK functional potential and response to micro-environmental challenges.39,49,50

The functional outcome of the downregulation of CD16-associated signaling elements in obinutuzumab-experienced cells is an increased potential to produce IFNγ in response to target stimulation or cytokines (Fig. 5B and C), revealing that CD16 ligation under high-affinity conditions may prime the cells to a reduced signaling threshold, thereby facilitating stronger effector responses; on this purpose, we are currently investigating the molecular mechanisms involved in NK priming resulting from high-affinity ligation conditions.

MAb-experienced NK cells appears desensitized to a subsequent rituximab re-stimulation, while they efficiently respond to obinutuzumab re-stimulation likely by virtue of the higher affinity binding (Fig. 5B). Such response is also observed in obinutuzumab-experienced cells despite a lower residual CD16 levels and a deeper FcεRIγ deficiency (Fig. 5A).

It is tempting to speculate that, in obinutuzumab-primed cells, the favored coupling of CD16 to residual CD3ζ chain may led to more robust and efficient biochemical signals given the quantitative differences in ITAM motif (three ITAM in CD3ζ vs one ITAM in FcεRIγ), thus rendering the response more efficient.

Moreover, the residual levels of CD3ζ chain observed in anti-CD20 experienced cells may preserve the co-stimulatory activity of CD2/CD58 interaction during Raji cell contact.32

We observed that the reduction of FcεRIγ and, to a lesser extent of CD3ζ, along with Syk kinase, dramatically impairs the ability to kill target cells depending on the engagement of NKp46 and NKp30 receptors (Fig. 4A), whose signaling ability relies on such signaling elements.29 The reduced cytolytic potential that was observed at significant levels both in rituximab- and obinutuzumab-experienced cells indicates that the residual CD3ζ levels are not sufficient to guarantee the optimal signals required for degranulation. Indeed, the observation of a defective cytotoxicity in F/F donors, where obinutuzumab selectively induces the degradation of FcεRIγ, corroborates the non-redundant role of such adaptor in ITAM receptor-dependent killing. On this issue, a different coupling of CD3ζ and FcεRIγ chains to downstream signaling intermediates has been demonstrated.51

Notably, the reduced level of Syk kinase in experienced cells may also contribute to the killing defect since a non-redundant role for such kinase has been described both for CD16- and NCR-dependent killing.52,53

Not very surprising is the observation that in F/F donors, rituximab-experienced cells exhibit a marginal but still significant defect of NKp30- and NKp46-mediated cytotoxicity despite the lack of CD16 adaptor degradation; indeed, under low-affinity ligation conditions, receptor-driven inhibitory signals may occur.30

In line with the reduced levels of CD16, we also observed a reduced ability to execute ADCC in anti-CD20 experienced NK cells (Fig. 4A); notably, such NK exhaustion may be rescued by IL-2 treatment, as previously demonstrated by different groups.54,30

In conclusion, we demonstrate that CD16 ligation by Fc optimized antitumor mAb obinutuzumab may shift NK functional program toward cytokine production. Taking into account the capability of mAbbased therapy to prime antitumor long-lasting T-cell responses, the socalled “vaccinal effect,”55,56 and the well-recognized role of NK-derived IFNγ in promoting DC maturation and the development of adaptive responses,25-27 NK cells, besides short-term cytotoxic properties, may be actors in promoting an antitumor response, thus reducing the risk of tumor-escape and relapse. These preclinical results appear worthy of further clinical investigation.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The following anti-CD20 mAbs were used: the chimeric IgG1κ type I rituximab, the humanized IgG1κ type II obinutuzumab (GA101) and its non-glycoengineered parental molecule (wt-GA101) kindly provided by Roche Glycart (Schlieren, Switzerland); the monovalent Fab fragment of obinutuzumab (GA101-Fab) obtained by papain digestion by commercial Fab Preparation kit (Thermo Scientific, code 44985), according to manufacturer's instructions. Anti-CD16 (B73.1, provided by Dr. G. Trinchieri National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Frederick, USA), anti-2B4 (C1.7, Beckman Coulter), anti-NKp46 (9E2, BioLegend), anti-NKG2D (149810, R&D Systems) anti-NKp30 (210847, R&D Systems), goat-anti-mouse (GAM) F(ab')2 (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). The following fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs for NKG2D (149810, R&D Systems), CD107a (H4A3, BD Biosciences), CD16 (Leu11c, BD Biosciences, MEM-154, Immunological Sciences, 3G8, BD Biosciences), NKp46 (9E2, BD Biosciences), NKp30 (p30-15, BD Biosciences), CD56 (NCAM16.2, or B159, BD Biosciences), CD3 (SK7, BD Biosciences), IFNγ (B27, BD Biosciences) and the goat-anti-human (GAH) κ light chain (Cappel) Ab were used. For immunoblot analysis were used the following Abs: anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10, Millipore), anti-FcεRIγ subunit (Millipore), anti-ZAP-70 (2F3.2, Millipore), anti-ubiquitin (FK2, Enzo Life Sciences), anti-CD3ζ (6B10.2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-Syk (4D10 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-β-tubulin (Tub2.1, Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell systems

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were freshly isolated from whole peripheral blood samples of healthy donors of Transfusion Center of Sapienza University of Rome over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. The study was conducted according to protocols approved by our local institutional review board and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinky. Where indicated, primary cultured human NK cells were obtained from 10-d co-cultures of PBMC with irradiated Epstein–Barr virus positive (EBV+) RPMI 8866 lymphoblastoid cell line.57 Experiments were performed on NK cells (CD3−CD56+) more than 80% pure.

The following cell lines were used as targets: the human CD20+ lymphoblastoid Raji, provided by Dr. F.D. Batista (Cancer Research UK, London) and the murine FcR+ mastocytoma P815, all kept in culture for less than 2 consecutive months in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% L-glutamine. Cells were counted in a counting chamber and checked for cell viability by trypan blue staining. Only samples with viability more than 90% were used. All cell lines were regularly checked for mycoplasma negativity.

Anti-CD20-mediated CD16 aggregation

CD20+ Raji cells were opsonized by incubating with saturating dose of rituximab (1 μg/106), obinutuzumab (0.1 μg/106), wt-GA101 (0.1 μg/106) or GA101-Fab (1 μg/106), for 20 min at room temperature. Non-opsonized Raji, used as control, and anti-CD20 opsonized targets were washed and allowed to interact with NK cells (E:T = 2:1) for the indicated times.

To obtain anti-CD20 “experienced” NK cells, Raji cells were loaded with 10 μg/mL of EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, code 21331) for 30 min at room temperature and then opsonized with rituximab or obinutuzumab, as above described. NK cells were mixed (2:1) with targets and co-cultured for the indicated times and then recovered by negative selection on streptavidin-coated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, code 11047).30 For experiments requiring lysosomal inhibitor, 20 mM NH4Cl (Sigma-Aldrich, code A4514) was added during co-culture. Where indicated, anti-CD20-experienced NK cells were re-plated in culture medium for up to 48 h.

Cytofluorimetric analysis

To determine the minimum saturating dose of anti-CD20 mAbs, Raji cells (1×106) were incubated with increasing amounts (0.05 μg, 0.1 μg, 1 μg, 10 μg, 100 μg) of rituximab, obinutuzumab (GA101), wt-GA101 or GA101-Fab for 20 min at 4 °C and then stained with FITC-conjugated GAH κ light chain Ab.

To determine FcγRIIIA-158V/F allotype, PBMCs from a cohort of 125 donors were stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD56 and the following anti-CD16 mAbs: FITC-conjugated 3G8, that binds to a not polymorphic epitope of CD16, or FITC-conjugated MEM-154, whose binding to CD16 is dependent on the presence of valine.33 The ratio between the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MEM-154 and 3G8 allows to classify three different phenotypes: F/F (ratio <0.04), V/V (ratio >0.62), and V/F (ratio between 0.15 and 0.48).

For CD16-mediated CD107a mobilization and intracellular IFNγ production, NK cells were combined (2:1) with non-opsonized or anti-CD20-opsonized Raji targets for 6 h at 37 °C in the presence of PE-conjugated anti-CD107a mAb and 50 μM Monensin (Golgi-stop; Sigma-Aldrich, code M5273). After the first hour, 10 μg/mL Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich, code B7651) was added. At the end of stimulation, cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 5 mM EDTA to obtain conjugate disruption and, before fixing (2% paraformaldehyde, Sigma-Aldrich, code 158127), cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD56 and PerCP-conjugated anti-CD3 mAbs. Samples were then permeabilized by incubating for 30 min at room temperature with 0.5% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich, code S4521) in PBS supplemented with 1% FCS and then stained with APC-conjugated anti-IFNγ mAb.

To determine CD107a surface expression in response to activating receptors, anti-CD20-experienced NK populations were stimulated with plastic-immobilized anti-CD16 (B73.1), anti-NKG2D, anti-NKp46 and anti-2B4 mAbs, alone or in combination and treated as described above.

To evaluate CD16 modulation, NK cells were mixed (2:1) with non-opsonized or anti-CD20-opsonized Raji targets, centrifuged for 1 min at 1000 rpm to allow conjugate formation and incubated for different times at 37 °C. To block the stimulation, samples were treated with 0.1% NaN3 in cold PBS for 5 min on ice and then washed with PBS supplemented with 5 mM EDTA to obtain conjugate disruption. Prior to fix (1% paraformaldehyde), cells were stained with PE- and APC-conjugated anti-CD16 and anti-CD56 mAbs, respectively. Normalized MFI was calculated for each time point as follows: (MFI of the stimulated sample/MFI of Ctrl sample) × 100, assuming as 100% the MFI value of NK cells stimulated with non-opsonized target for each time of stimulation. To examine activating receptor expression levels, anti-CD20-experienced NK populations were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD16, anti-NKp46, anti-NKp30 or anti-NKG2D mAbs. All results were analyzed using FlowJo version 9.3.2 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Confocal microscopy

To evaluate the co-localization of CD16 with the lysosomal compartment, NK cells were pre-treated for 30 min at 37 °C with 10 μM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Life Technologies, code L-7528), and then allowed to interact (2:1) with 7-amino-4-cholromethylcoumarin (CMAC)-labeled (Life Technologies, code C2110) non-opsonized or anti-CD20-opsonized Raji cells. Conjugates were gently re-suspended and spun onto poly-L-lysine-coated glass slides as described previously,58 incubated for 15 min at 37 °C followed by incubation at 4 °C for 10 min to promote spontaneous adhesion. Cells were fixed (3.7% paraformaldehyde), permeabilized (0.5% saponin), incubated with 0.1 M glycin (Bio-Rad, code 161-0718) followed by blocking buffer (1% FCS, 0.05% saponin) and stained with anti-CD16 followed by Alexa Fluor 488-labeled GAM (Invitrogen) Abs. High-resolution images (800 × 800 pixel, 8 μs/pixel) were acquired, on randomly acquired fields, with a IX83 FV1200 laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus) with a 60×/1.35 NA UPlanSAPO oil immersion objective. Sequential acquisition was used to avoid crosstalk between different fluorophores.46 Fluorescence and DIC (Differential Interference Contrast) images were acquired with zoom3. Co-localization was assessed in NK/Raji conjugates (n = 50) showing an extensive membrane contact between effector and target cells and expressed as percentage of conjugates containing co-localized CD16 and lysosomes with respect to total conjugates, considering co-localization indexes (Pearson's correlation coefficient >0.2) obtained by FluoView 4.2 software, between two channels on single cells (ROI) after background correction. Images were processed with ImageJ1.41o software.

CD16 polymorphism analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from PBMCs by commercial Isolate II Genomic DNA kit (Bioline) in a cohort of 125 healthy donors. The genomic region containing the polymorphic c.559 site was amplified by two distinct PCR assays, as described.34,35 Specifically, for PCR assay 1, PCR primers: forward1 5′-CCCTTCACAAAGCTCTGCACT-3′; reverse1 5′-ATTCTGGAGGCTGGTGCTACA-3′; sequencing primer: 5′-CCCCAAAAGAATGGACTGAA-3′: for PCR assay 2, PCR primers: forward2 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCATCATAATTCTGACCTCT-3′, reverse2 5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCTTGAGTGATGGTGATGTTCA-3′; sequencing primers: 21M13 or M13. PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed by the Sequencing Software Analysis 6 (Applied Biosystems).

Biochemical analysis

To analyze CD16-associated signaling element expression levels, NK cells were lysed in 1% Triton-X 100 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA pH8, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4) supplemented with 1 μg/mL each of aprotinin, leupeptin and when required with 5 mM N-ethyl-maleimide. Equal amount of proteins from each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblot analysis. To explore Syk ubiquitination, CD16 stimulation was obtained by mixing primary cultured human NK cells with non-opsonized or anti-CD20-opsonized Raji cells for the indicated times. Before mixing, targets cells were fixed (0.5% paraformaldehyde) for 5 min at room temperature, washed three times in complete medium, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and washed once more. At the end of stimulation, samples were lysed as above described and immunoprecipitated with anti-Syk-pre-loaded protein G Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich, code P3296).

Evaluation of cytotoxic activity and IFNγ release

For ADCC activity, rituximab- or obinutuzumab-opsonized or non-opsonized 51Cr-labeled Raji were used as targets. For redirected killing assay, NK cells were incubated with FcR+ P815 targets in the presence of anti-CD16, anti-NKp46, anti- NKp30 or anti-NKG2D mAbs.

Maximal and spontaneous release was obtained by incubating 51Cr-labeled individual targets, as used for each stimulation condition, with SDS 10% or medium alone, respectively. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated according to the formula: percentage of specific release = (experimental-spontaneouns release)/(total-spontaneous release) × 100. Lytic units for 1 × 106 effector cells were calculated as follows: 1 × 106 /(no. of target cells × X), where X is the E:T ratio resulting in 10% specific lysis.

For IFNγ release, anti-CD20-experienced NK cells were mixed (2:1) with the indicated targets in the presence or absence of recombinant human IL-12 (10 ng/mL) (Peprotech, code 200–12) or IL-2 (100 U/mL) (R&D Systems, code 202-IL), for 18 h. Supernatants were collected and analyzed by commercial ELISA kit (Thermo Scientific, code EHIFNG2), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical and densitometric analysis

Differences among multiple groups were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test correction, by Friedman with Dunn's post-test correction, or by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test correction, as appropriated. Differences between two groups were determined by performing Wilcoxon matched pairs test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p value was less than 0.05. Analyses were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad). Quantification of specific bands was performed with ImageJ1.41o software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center for Nanosciences (Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Rome, Italy) for providing wide access to the microscopy facility and, in particular, we are grateful to Dr. Valeria de Turris and Dr. Simone De Panfilis for assistance and advices. D. Milana and P. Birarelli for technical support with primary NK cell cultures.

Funding

This work was supported by grant from Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC and AIRC 5×1000), by Italian Ministry for University and Research (MIUR) SIR 2014 (RBSI14022M) to Cristina Capuano and by Sapienza University of Rome (Ateneo).

References

- 1.Lim SH, Beers SA, French RR, Johnson PW, Glennie MJ, Cragg MS. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies: historical and future perspectives. Haematologica 2010; 95(1):135-43; PMID:19773256; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3324/haematol.2008.001628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illidge T, Klein C, Sehn LH, Davies A, Salles G, Cartron G. Obinutuzumab in hematologic malignancies: lessons learned to date. Cancer Treat Rev 2015; 41(9):784-92; PMID:26190254; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, Engelke A, Eichhorst B, Wendtner CM, Chagorova T, de la Serna J, Dilhuydy MS, Illmer T et al.. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(12):1101-10; PMID:24401022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, Dueck G, Trněný M, Bouabdallah K, Fowler N, Delwail V, Press O, Salles G et al.. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(8):1081-93; PMID:27345636; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein C, Lammens A, Schäfer W, Georges G, Schwaiger M, Mössner E, Hopfner KP, Umaña P, Niederfellner G. Epitope interactions of monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20 and their relationship to functional properties. MAbs 2013; 5(1):22-33; PMID:23211638; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/mabs.22771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bologna L, Gotti E, Manganini M, Rambaldi A, Intermesoli T, Introna M, Golay J. Mechanism of action of type II, glycoengineered, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody GA101 in B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia whole blood assays in comparison with rituximab and alemtuzumab. J Immunol 2011; 186(6):3762-9; PMID:21296976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1000303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mössner E, Brünker P, Moser S, Püntener U, Schmidt C, Herter S, Grau R, Gerdes C, Nopora A, van Puijenbroek E et al.. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood 2010; 115(22):4393-402; PMID:20194898; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herter S, Birk MC, Klein C, Gerdes C, Umana P, Bacac M. Glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies enhances monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytosis and cytotoxicity. J Immunol 2014; 192(5):2252-60; PMID:24489098; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1301249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golay J, Da Roit F, Bologna L, Ferrara C, Leusen JH, Rambaldi A, Klein C, Introna M. Glycoengineered CD20 antibody obinutuzumab activates neutrophils and mediates phagocytosis through CD16B more efficiently than rituximab. Blood 2013; 122(20):3482-91; PMID:24106207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alduaij W, Ivanov A, Honeychurch J, Cheadle EJ, Potluri S, Lim SH, Shimada K, Chan CH, Tutt A, Beers SA et al.. Novel type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (GA101) evokes homotypic adhesion and actin-dependent, lysosome-mediated cell death in B-cell malignancies. Blood 2011; 117(17):4519-29; PMID:21378274; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagez AL, Cartron G. Obinutuzumab: a new class of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Curr Opin Oncol 2014; 26(5):484-91; PMID:25014645; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalvao F, Garcia Z, Celli S, Breart B, Deguine J, Van Rooijen N, Bousso P. The mechanism of anti-CD20-mediated B cell depletion revealed by intravital imaging. J Clin Invest 2013; 123(12):5098-103; PMID:24177426; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI70972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, Ravetch JV, Poe JC, Haas KM, Tedder TF. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2004; 199(12):1659-69; PMID:15210744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20040119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandjean CL, Montalvao F, Celli S, Michonneau D, Breart B, Garcia Z, Perro M, Freytag O, Gerdes CA, Bousso P. Intravital imaging reveals improved Kupffer cell-mediated phagocytosis as a mode of action of glycoengineered anti-CD20 antibodies. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34382; PMID:27698437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep34382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deligne C, Metidji A, Fridman WH, Teillaud JL. Anti-CD20 therapy induces a memory Th1 response through the IFN-γ/IL-12 axis and prevents protumor regulatory T-cell expansion in mice. Leukemia 2015; 29(4):947-57; PMID:25231744; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/leu.2014.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheadle EJ, Lipowska-Bhalla G, Dovedi SJ, Fagnano E, Klein C, Honeychurch J, Illidge TM. A TLR7 agonist enhances the antitumor efficacy of obinutuzumab in murine lymphoma models via NK cells and CD4 T cells. Leukemia 2017; PMID:27890931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/leu.2016.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pincetic A, Bournazos S, DiLillo DJ, Maamary J, Wang TT, Dahan R, Fiebiger BM, Ravetch JV. Type I and type II Fc receptors regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol 2014; 15(8):707-16; PMID:25045879; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, Solal-Celigny P, Bardos P, Colombat P, Watier H. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood 2002; 99(3):754-8; PMID:11806974; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood.V99.3.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persky DO, Dornan D, Goldman BH, Braziel RM, Fisher RI, Leblanc M, Maloney DG, Press OW, Miller TP, Rimsza LM. Fc gamma receptor 3a genotype predicts overall survival in follicular lymphoma patients treated on SWOG trials with combined monoclonal antibody plus chemotherapy but not chemotherapy alone. Haematologica 2012; 97(6):937-42; PMID:22271896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3324/haematol.2011.050419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rascu A, Repp R, Westerdaal NA, Kalden JR, van de Winkel JG. Clinical relevance of Fc gamma receptor polymorphisms. Ann NY Acad Sci 1997; 815:282-95; PMID:9186665; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terszowski G, Klein C, Stern M. KIR/HLA interactions negatively affect rituximab- but not GA101 (obinutuzumab)-induced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Immunol 2014; 192(12):5618-24; PMID:24795454; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1400288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herter S, Herting F, Mundigl O, Waldhauer I, Weinzierl T, Fauti T, Muth G, Ziegler-Landesberger D, Van Puijenbroek E, Lang S et al.. Preclinical activity of the type II CD20 antibody GA101 (obinutuzumab) compared with rituximab and ofatumumab in vitro and in xenograft models. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12(10):2031-42; PMID:23873847; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinchieri G, Valiante N. Receptors for the Fc fragment of IgG on natural killer cells. Nat Immun 1993; 12(4–5):218-34; PMID:8257828 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long EO, Kim HS, Liu D, Peterson ME, Rajagopalan S. Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:227-58; PMID:23516982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walzer T, Dalod M, Robbins SH, Zitvogel L, Vivier E. Natural-killer cells and dendritic cells: “l'union fait la force”. Blood 2005; 106(7):2252-8; PMID:15933055; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martín-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol 2004; 5(12):1260-5; PMID:15531883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crouse J, Xu HC, Lang PA, Oxenius A. NK cells regulating T cell responses: mechanisms and outcome. Trends Immunol 2015; 36(1):49-58; PMID:25432489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letourneur O, Kennedy IC, Brini AT, Ortaldo JR, O'Shea JJ, Kinet JP. Characterization of the family of dimers associated with Fc receptors (Fc epsilon RI and Fc gamma RIII). J Immunol 1991; 147(8):2652-6; PMID:1833456 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruse PH, Matta J, Ugolini S, Vivier E. Natural cytotoxicity receptors and their ligands. Immunol Cell Biol 2014; 92(3):221-9; PMID:24366519; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/icb.2013.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capuano C, Romanelli M, Pighi C, Cimino G, Rago A, Molfetta R, Paolini R, Santoni A, Galandrini R. Anti-CD20 therapy acts via FcγRIIIA to diminish responsiveness of human natural killer cells. Cancer Res 2015; 75(19):4097-108; PMID:26229120; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood 2010; 115(11):2167-76; PMID:19965656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grier JT, Forbes LR, Monaco-Shawver L, Oshinsky J, Atkinson TP, Moody C, Pandey R, Campbell KS, Orange JS. Human immunodeficiency-causing mutation defines CD16 in spontaneous NK cell cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest 2012; 122(10):3769-80; PMID:23006327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI64837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Böttcher S, Ritgen M, Brüggemann M, Raff T, Lüschen S, Humpe A, Kneba M, Pott C. Flow cytometric assay for determination of FcgammaRIIIA-158 V/F polymorphism. J Immunol Methods 2005; 306(1–2):128-36; PMID:16181633; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jim.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quartuccio L, Fabris M, Pontarini E, Salvin S, Zabotti A, Benucci M, Manfredi M, Biasi D, Ravagnani V et al.. The 158 VV Fcgamma receptor 3° genotype is associated with response to rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: results of an Italian multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73(4):716-21; PMID:23505228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leppers-van de Straat FG, van der Pol WL, Jansen MD, Sugita N, Yoshie H, Kobayashi T, van de Winkel JG. A novel PCR-based method for direct Fc gamma receptor IIIa (CD16) allotyping. J Immunol Methods 2000; 242(1–2):127-32; PMID:10986395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paolini R, Molfetta R, Piccoli M, Frati L, Santoni A. Ubiquitination and degradation of Syk and ZAP-70 protein tyrosine kinases in human NK cells upon CD16 engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98(17):9611-6; PMID:11493682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.161298098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood 2006; 107(1):159-66; PMID:16150947; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajasekaran K, Kumar P, Schuldt KM, Peterson EJ, Vanhaesebroeck B, Dixit V, Thakar MS, Malarkannan S. Signaling by Fyn-ADAP via the Carma1-Bcl-10-MAP3K7 signalosome exclusively regulates inflammatory cytokine production in NK cells. Nat Immunol 2013; 14(11):1127-36; PMID:24036998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Zhang T, Hwang I, Kim A, Nitschke L, Kim M, Scott JM, Kamimura Y, Lanier LL, Kim S. Epigenetic modification and antibody-dependent expansion of memory-like NK cells in human cytomegalovirus-infected individuals. Immunity 2015; 42(3):431-42; PMID:25786175; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joyce MG, Tran P, Zhuravleva MA, Jaw J, Colonna M, Sun PD. Crystal structure of human natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp30 and identification of its ligand binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108(15):6223-8; PMID:21444796; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1100622108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freeman CL, Morschhauser F, Sehn L, Dixon M, Houghton R, Lamy T, Fingerle-Rowson G, Wassner-Fritsch E, Gribben JG, Hallek M et al.. Cytokine release in patients with CLL treated with obinutuzumab and possible relationship with infusion-related reactions. Blood 2015; 126(24):2646-9; PMID:26447188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2015-09-670802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox MC, Battella S, La Scaleia R, Pelliccia S, Di Napoli A, Porzia A, Cecere F, Alma E, Zingoni A, Mainiero F et al.. Tumor-associated and immunochemotherapy-dependent long-term alterations of the peripheral blood NK cell compartment in DLBCL patients. Oncoimmunology 2015; 4(3):e990773; PMID:25949906; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/2162402X.2014.990773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veeramani S, Wang SY, Dahle C, Blackwell S, Jacobus L, Knutson T, Button A, Link BK, Weiner GJ. Rituximab infusion induces NK activation in lymphoma patients with the high-affinity CD16 polymorphism. Blood 2011; 118(12):3347-9; PMID:21768303; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowles JA, Weiner GJ. CD16 polymorphisms and NK activation induced by monoclonal antibody-coated target cells. J Immunol Methods 2005; 304(1–2):88-99; PMID:16109421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romee R, Foley B, Lenvik T, Wang Y, Zhang B, Ankarlo D, Luo X, Cooley S, Verneris M, Walcheck B et al.. NK cell CD16 surface expression and function is regulated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM17). Blood 2013; 121(18):3599-608; PMID:23487023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2012-04-425397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quatrini L, Molfetta R, Zitti B, Peruzzi G, Fionda C, Capuano C, Galandrini R, Cippitelli M, Santoni A, Paolini R. Ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of NKG2D-DAP10 receptor complexes activates signaling and functions in human NK cells. Sci Signal 2015; 8(400):ra108; PMID:26508790; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scisignal.aab2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor RP, Lindorfer MA. Fcγ-receptor-mediated trogocytosis impacts mAb-based therapies: historical precedence and recent developments. Blood 2015; 125(5):762-6; PMID:25498911; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2014-10-569244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlums H, Cichocki F, Tesi B, Theorell J, Beziat V, Holmes TD, Han H, Chiang SC, Foley B, Mattsson K et al.. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of NK cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity 2015; 42(3):443-56; PMID:25786176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang T, Scott JM, Hwang I, Kim S. Cutting edge: antibody-dependent memory-like NK cells distinguished by FcRγ deficiency. J Immunol 2013; 190(4):1402-6; PMID:23345329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1203034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cerwenka A, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16(2):112-23; PMID:26806484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri.2015.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galandrini R, Palmieri G, Paolini R, Piccoli M, Frati L, Santoni A. Selective binding of shc-SH2 domain to tyrosine-phosphorylated zeta but not gamma-chain upon CD16 ligation on human NK cells. J Immunol 1997; 159(8):3767-73; PMID:9378963 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Negishi I, Motoyama N, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Senju S, Hatakeyama S, Zhang Q, Chan AC, Loh DY. Essential role for ZAP-70 in both positive and negative selection of thymocytes. Nature 1995; 376(6539):435-8; PMID:7630421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/376435a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hesslein DG, Palacios EH, Sun JC, Beilke JN, Watson SR, Weiss A, Lanier LL. Differential requirements for CD45 in NK-cell function reveal distinct roles for Syk-family kinases. Blood 2011; 117(11):3087-95; PMID:21245479; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhat R, Watzl C. Serial killing of tumor cells by human natural killer cells – enhancement by therapeutic antibodies. PLoS One 2007; 2(3):e326; PMID:17389917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. Differential Fc-receptor engagement drives an anti-tumor vaccinal effect. Cell 2015; 161(5):1035-45; PMID:25976835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abès R, Gélizé E, Fridman WH, Teillaud JL. Long-lasting antitumor protection by anti-CD20 antibody through cellular immune response. Blood 2010; 116(6):926-34; PMID:20439625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Capuano C, Paolini R, Molfetta R, Frati L, Santoni A, Galandrini R. PIP2-dependent regulation of Munc13-4 endocytic recycling: impact on the cytolytic secretory pathway. Blood 2012; 119(10):2252-62; PMID:22271450; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molfetta R, Quatrini L, Capuano C, Gasparrini F, Zitti B, Zingoni A, Galandrini R, Santoni A, Paolini R. c-Cbl regulates MICA- but not ULBP2-induced NKG2D down-modulation in human NK cells. Eur J Immunol 2014; 44(9):2761-70; PMID:24846123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.201444512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.