Abstract

Background:

Falls are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults. About a third of those aged 65 years or older fall at least once each year, which can result in hospitalizations, hip fractures and nursing home admissions that incur high costs to individuals, families and society. The objective of this clinical review was to assess the risk of falls in ambulatory older adults who take antiepileptic drugs, medications that can increase fall risk and decrease bone density.

Methods:

PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library electronic databases were searched from inception to July 2014. Case-control, quasi-experimental and observational design studies published in English that assessed quantifiable fall risk associated with antiepileptic drug use in ambulatory patient populations with a mean or median age of 65 years or older were eligible for inclusion. One author screened all titles and abstracts from the initial search. Two authors independently reviewed and abstracted data from full-text articles that met eligibility criteria.

Results:

Searches yielded 399 unique articles, of which 7 met inclusion criteria—4 prospective or longitudinal cohort studies, 1 cohort study with a nested case-control, 1 cross-sectional survey and 1 retrospective cross-sectional database analysis. Studies that calculated the relative risk of falls associated with antiepileptic drug use reported a range of 1.29 to 1.62. Studies that reported odds ratios of falls associated with antiepileptic drug use ranged from 1.75 to 6.2 for 1 fall or at least 1 fall and from 2.56 to 7.1 for more frequent falls.

Discussion:

Health care professionals should monitor older adults while they take antiepileptic drugs to balance the need for such pharmacotherapy against an increased risk of falling and injuries from falls.

Knowledge Into Practice.

Falls are a leading cause of injury and injury-related deaths among older adults, which can place a significant health and financial burden on individuals, their families and health care systems.

Antiepileptic drug use among ambulatory older adults leads to increased risk of falling similar to, or greater than, other psychotropic agents such as benzodiazepines, antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Health care professionals directly involved with patient care should monitor older adults while they are taking antiepileptic drugs to balance the need for such pharmacotherapy against an increased risk of falling.

Mise En Pratique Des Connaissances.

Les chutes représentent l’une des principales causes de blessures et de décès associés aux blessures chez les personnes âgées. Dans certains cas, elles imposent aux personnes, à leur famille et aux systèmes de soins de santé un fardeau financier et une charge pour la santé.

L’usage d’antiépileptiques chez les personnes âgées ambulatoires conduit à une augmentation du risque de chute semblable ou plus grande que d’autres agents psychotropes, comme les benzodiazépines, les antidépresseurs et les antipsychotiques.

Les professionnels de la santé qui prodiguent des soins directs aux patients devraient surveiller les personnes âgées lorsque celles-ci prennent un antiépileptique afin de mesurer la pertinence de ce type de médicaments par rapport au risque de chute.

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that 1 in 3 people over the age of 65 years falls at least once annually.1 Falls account for approximately a third of injury-related hospital admissions in older adults,2 90% of hip fractures and a 20% mortality rate within a year of a hip fracture.3-5 These outcomes collectively place a significant burden on individuals, families and the health care system. The 1998 Health Canada SMART-RISK analysis estimated that a 20% reduction in falls would result in 7500 fewer hospitalizations and a national savings of some $138 million annually.6

A number of factors put older adults at increased risk for falls, among them vascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, arthritis, impaired mobility and gait, deconditioning and immobility, reduced visual acuity and foot problems.7 Compounding these risk factors are changes in susceptibility to the pharmacodynamic effects of medications with increasing age, which amplify the central nervous system–acting effects of drugs and result in symptoms that include ataxia, sedation, confusion, dizziness and blurred vision.8 Such adverse effects are commonly encountered with benzodiazepines, antihypertensives and antidepressants.9 Indeed, the risk of falls from benzodiazepines is well established in meta-analyses,10,11 and in one systematic review, several classes of drugs, including psychotropic medications, antidepressants, neuroleptics and cardiovascular medications, were also found to increase the risk of falls.12 However, it is unclear in these meta-analyses10,11 whether the classification of psychotropic medications included antiepileptics and neither study reported the risk of falls with antiepileptics as a drug class. Furthermore, these meta-analyses incorporated populations from both community and long-term care environments. Deandrea et al.’s systematic review13 and meta-analysis of studies investigating the contribution of multiple factors to the risk of falling among community-dwelling older adults demonstrated an odds ratio (OR) of 1.88 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02-3.49) with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). This meta-analysis included only 4 studies, of which only 1 had investigated the risk associated with phenytoin rather than antiepileptics in general. Studies published since then have reported ORs of 2.114 and 2.815 for falling among AED users. However, differences in the populations investigated, outcomes measured and risk reported complicate the interpretation of risk of falling with AED use.

The incidence of epilepsy has 2 peaks—the first in early childhood and the second in older adults—and among those aged 75 years and older, the incidence increases 2- to 3-fold.16-18 This is concerning because seizures themselves can increase the risk of falls and the adverse effects of AEDs, which include ataxia, sedation, confusion, dizziness and blurred vision, can also increase fall risk.19 With aging populations and expected increases in AED use, not only to treat seizures but also conditions such as pain, it is imperative that the risk of falls with AED use in community-dwelling older adults is well established.

The aim of this clinical review was to assess the risk of falls in ambulatory older adults who are taking AEDs. This review synthesizes findings from a range of studies with a goal of guiding primary care providers who seek to balance the need for AED therapy against the increased risk of falling and consequent injury, especially in at-risk older adults.

Methods

This review assessed fall risk in ambulatory older adults, which we defined as individuals with a mean or median age of 65 years or older whose primary residence was in the community, not in nursing homes, long-term care homes or hospitals.

Data sources and search strategy

A single reviewer (M.M.) searched PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library electronic database from their first indexed records up to July 2014 using Boolean operators AND and OR with the following terms: falls, elderly, aged, older adults, antiepileptics, antiepileptics and anti-seizure medications. Searches were also conducted using each of the following AED names in combination with the search terms outlined above: phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, primidone, valproic acid/valproate/valproex, lamotrigine, zonisamide, topiramate, levetiracetam, felbamate, ethosuximide, rufinamide, tiagabine, vigabatrin, pregabalin and gabapentin.

Bibliographies of eligible studies were searched for additional relevant studies. Drug monographs of AEDs in e-Therapeutics Canada, the Canadian Drug Product Database and international monographs (i.e., Epocrates) were also searched to determine fall risk in ambulatory older adults. Search results were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Mendeley,20 a free online reference management system, was used to share and discuss articles selected for full review.

Study selection

One reviewer (M.M.) screened all titles and abstracts from the initial search. Two reviewers (M.M. and T.P.) independently reviewed all full-text articles after the initial screen for eligibility. Any discrepancies during the eligibility screening, data abstraction and study quality assessment processes were resolved by discussion to reach consensus.

Studies were included if participants were older adult ambulatory patients. Studies were excluded if their participants were on concurrent benzodiazepines or if they had a history of drop attacks or disease states that independently increase the risk of falls for which data analysis was not provided or conducted separately. Studies were excluded if it was evident that falls resulted from external factors, such as those caused by uneven surfaces. Studies investigating interventions to reduce the risk of falls were excluded.

Eligible studies were limited to those published in English. Randomized controlled, case-control, quasi-experimental and observational studies and reviews were eligible for inclusion, but case reports and case series were excluded. Studies that did not include a comparative analysis of AEDs were excluded.

Only studies that reported quantifiable data on falls were included. Studies that lacked sufficient data on falls to allow assessment of risk were excluded, as were those that assessed or presented the risk of falls with AEDs in combination with other agents. In addition, studies that reported the risk of fractures but not of falls were excluded, as were those that did not separate inpatient and outpatient data. Studies that reported data on patients taking benzodiazepines and who had risk factors that increased the likelihood of falls were included provided that data on risk pertaining to AED use were analyzed separately.

Data abstraction and analysis

The following data were abstracted from studies: study design, location and duration, participant demographic details, AED details and falls. Reported relative risks (RRs), ORs and their related CIs were extracted. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.2 for Macintosh) was used to determine the RR for 1 study from prevalence data that were reported.

Study quality

The Effective Public Health Practice Project’s quality assessment tool for quantitative studies21 was used to determine the internal validity of selected studies and to assess the strengths and limitations of available literature on falls in ambulatory older adults (Box 1).

Box 1. Components of quantitative studies21.

Selection bias: whether participants in the study represent a target population and percentage of selected individuals who agree to participate

Study design: whether the study was randomized, method of randomization and appropriateness of the randomization method

Confounders: whether there were important differences between the groups and what percentage of relevant confounders was controlled

Blinding: whether the outcomes assessors were blinded, whether the participants were blinded

Data collection methods: whether data collection tools were valid and reliable

Withdrawals and dropouts: whether withdrawals and dropouts were reported and what percentage of participants completed the study

Intervention integrity: what percentage of participants received the allocated intervention, if the consistency of the intervention was measured and if it was likely that subjects received an unintended intervention

Analyses: unit of allocation, unit of analysis, whether statistical methods were appropriate and if analysis was intention to treat

Components 1 to 6 were rated strong, moderate or weak. Studies were given a global rating of strong (if no weak ratings), moderate (if 1 weak rating) and weak (if 2 or more weak ratings) (Table 1). Components 7 and 8 were not assessed because these components were unknown or absent.

Table 1.

Study quality

| Study assessed | Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection methods | Withdrawals and dropouts | Global rating scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cea-Soriano et al.14 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Not applicable | Moderate |

| Masud et al.15 | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Ensrud et al.22 | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Koski et al.23 | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Faulkner et al.24 | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Tromp et al.25 | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| French et al.26 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Not applicable | Weak |

Results

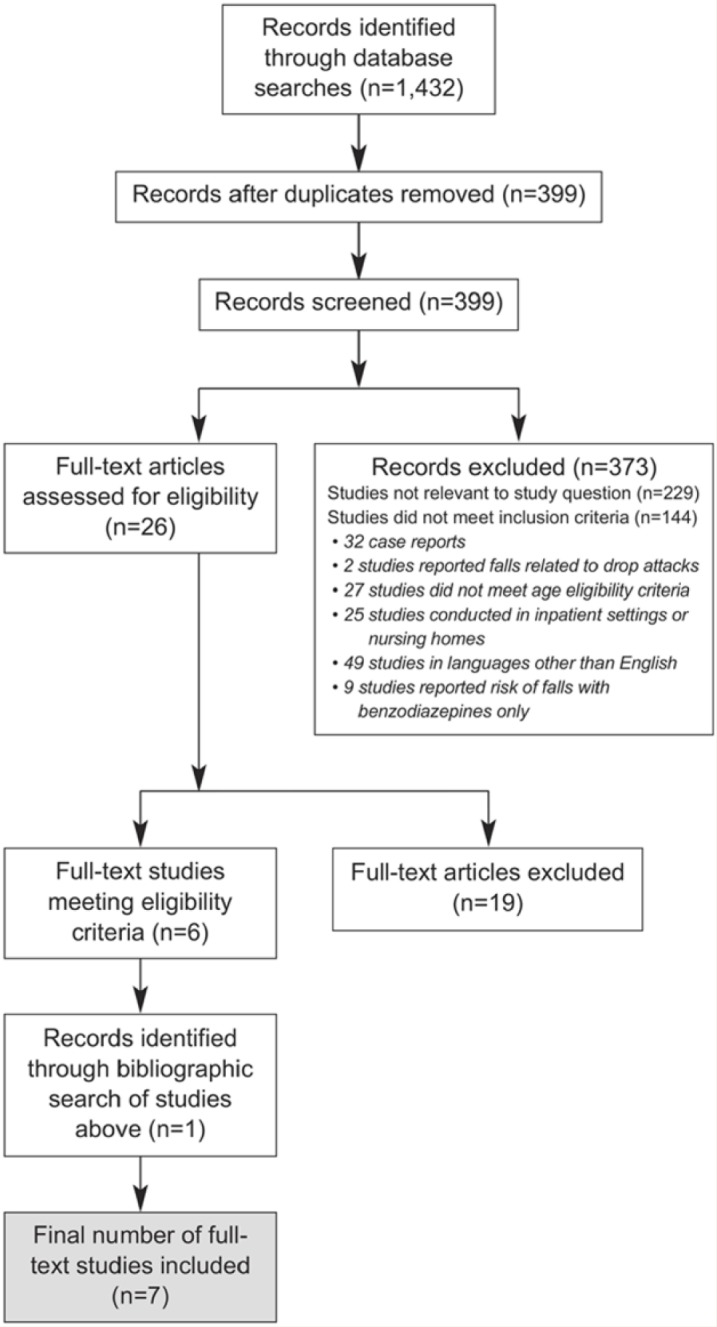

Electronic database searches yielded 1432 citations, of which 399 were unique articles. Of these, 229 were excluded, as review of their abstracts revealed that these studies were not relevant to our research question. Another 144 were excluded because the studies did not meet our inclusion criteria. After this initial screening, 26 articles were selected for full-text review by 2 reviewers (M.M. and T.P.). Of these, 19 were excluded for the following reasons: 10 studies reported insufficient data or results regarding falls, 5 were conducted in an inpatient or nursing home population, 1 was a literature review, 1 an editorial, 1 reported falls as a confounder and 1 investigated pharmacist intervention to reduce risk of falls. This left 6 studies that met the inclusion criteria. A search of the bibliographies of these articles yielded an additional study that met our inclusion criteria, bringing to 7 the number of studies in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process

Seventeen AED drug monographs were searched for data on falls; however, none provided adequate information on falls in older adult patients or citations for additional studies to include in this clinical review.

Study and participant characteristics

Of the 7 studies, 4 were prospective or longitudinal cohort studies,22-25 1 was a cohort study with nested case control,14 1 a cross-sectional survey,15 and 1 a retrospective cross-sectional database analysis.26 Studies varied in duration of data collection on falls from 1 year26 to a mean of 5.3 years of follow-up.14 One study asked participants to recall falls over the previous year.15 Sample sizes ranged from 20,551 patients in a retrospective cross-sectional Veterans Health Administration study26 to 979 persons in a prospective study among rural home-dwelling older adults.23 Two studies were on female-only participants22,24 and 1 on male-only participants.15 Participants in all studies were at least 65 years of age or the mean or median age of individuals comprising the study was more than 65 years.

Falls risk assessment

Risk of falls was reported as RR in 3 studies,23,24,26 as OR in 3 studies14,15,25 and as multivariate ORs in 1 study.22 Some studies reported the risk of falls, whereas others assessed the risk of recurrent falls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study and year of publication | Source of data for study, country | Period study data were collected or extracted from database | Study design | Sample size and population | Duration of study or follow-up | Outcome measures | Results |

RR or OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Nonusers | ||||||||

| French et al., 200626 | National Veterans Health Administration ambulatory event database (includes data from all 21 Veterans Integrated Service Networks), United States | 2004 | Retrospective, cross-sectional study (Veterans Health Administration) | 20,551 patients fall-related outpatient visits and 1+ medications and 20,551 controls (with nonspecific chest pain); 98% men Mean age: 78 y |

1 fiscal year | Percentage of fall-encoded events | 8.95% | 5.18% | RR: 1.29 (1.26–1.33) |

| Koski et al., 199623 | Home-dwelling residents from 5 rural municipalities (Hailuoto, Kempele, Kiiminki, Oulunsalo and Ylikiiminki) in Northern Finland | Jan. 1, 1991–Dec. 31, 1992 | Prospective cohort | 979 (602 women and 377 men) Age: ≥70 y |

2-y follow-up | Falls with use of AEDs | NA | NA | RR: 1.5 (1.20-1.87) |

| Faulkner et al., 200924 | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, (participants recruited from population-based lists in Baltimore, MD; Portland, OR; Minneapolis, MN; and the Monongahela Valley, PA), United States | Start and end dates not stated; analysis sample consisted of community-dwelling women, 65 y and older, who provided complete data on age, history of falls at baseline and incident falls over 4 y | Prospective cohort (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures) | 8378 women Mean age: 71 y |

4-y study; data collected every 4 mo, medication use over past 1 y | Falls among AED users vs. nonusers | NA | NA | RR: 1.62 (1.31-2.02) |

| Ensrud et al., 200222 | Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, (participants recruited from population-based lists in Baltimore, MD; Portland, OR; Minneapolis, MN; and the Monongahela Valley, PA), United States | Aug. 1992–Jul. 1994 | Prospective cohort (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures) | 8127 women of whom 123 were AED users; mean age among nonusers: 76.9 y; mean age among antiepileptic users: 77.6 y | Similar to Faulkner study; mean follow-up of 12 mo | Falls among AED users vs. nonusers (among those who fall at least once) Falls among AED users vs. nonusers (among those who fall frequently) |

NA NA |

NA NA |

OR: 1.75 (1.13-2.71) OR: 2.56 (1.49-4.41) |

| Tromp et al., 199825 | Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, random sample drawn from population registers of 11 municipalities, in 3 regions of the Netherlands | Baseline data collected in 1992 and study outcomes (occurrence of falls and fractures) assessed in 1995 | Prospective cohort (Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam) | 1469 (764 women and 705 men) Mean age: 72.6 y |

3-year follow-up; falls in the past year | AED use and falls (≥1 fall) | NA | NA | OR: 6.2 (2.0–19.7) |

| AED use and recurrent falls (2 falls) | NA | NA | OR: 7.1 (2.5-19.8) | ||||||

| Masud et al., 201315 | Study on Male Osteoporosis and Aging (SOMA), single-centre study of men living in the Funen County, Denmark | Random sample of 9314 men aged 60-75 y invited to participate in mail survey in autumn 2004 | Cross-sectional survey | 4696 men Age: median 66.3 y |

Falls in the previous year | AED use and falls | NA | NA | OR: 2.8 (1.5-5.1) |

| AED use and recurrent falls | NA | NA | OR: 2.6 (1.2-5.7) | ||||||

| Cea-Soriano et al., 201314 | Health Improvement Network Database, United Kingdom | Patients aged 40-89 y between Jan. 1, 2000 and Dec. 31, 2008 | Cohort with nested case-control (Health Improvement Network Database) | Random sample of 20,000 cases of falls of 105,700 Mean age at index date: 68.6 y for men, 69.1 y for women |

Mean follow-up of 5.3 y | Falls among AED users vs. nonusers | NA | NA | OR: 2.1 (1.8-2.3) |

AED = antiepileptic drug; RR= relative risk; OR = odds ratio.

In their prospective 4-year study of 8378 community-dwelling women with a mean age of 71 years, Faulkner et al.24 determined an RR of falls among users of antiepileptics of 1.62 (95% CI: 1.31-2.02). With a similar methodology and study intent, Koski et al.23 demonstrated in a 2-year study an RR of falls of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2-1.87) among 979 AED users aged 70 years or older.

In their 1-year retrospective cross-sectional study of Veterans Health Administration patients, French et al.26 found that patients using antiepileptics/barbiturates had more fall-encoded encounters (8.95%) than patients with nonspecific chest pain (5.18%). Although these researchers did not report RR, using data from the study, the authors of this review calculated an RR of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.26-1.33) using the percentage of fall-encoded events with AED use as the outcome measure.

Cea-Soriano et al.14 calculated an OR of 2.1 (95% CI: 1.8-2.3) for falls among users of AEDs in their nested case-control cohort study. Ensrud et al.22 calculated many multivariate ORs. Older adult patients taking AEDs had a multivariate OR of 1.75 (95% CI: 1.13-2.71) compared with nonusers. The study authors also found that patients taking AEDs had a multivariate OR of 2.56 (95% CI: 1.49-4.41) for frequent falls compared with nonusers.22 Among participants who reported a previous fall, AED users were 3.4 times more likely to fall at least once (multivariate OR: 3.44, 95% CI: 1.72-6.90) and 4.3 times more likely to fall multiple times (multivariate OR: 4.29, 95% CI: 2.14-8.63) than nonusers.22 However, these researchers found that if participants reported no previous falls, the odds of falling once (multivariate OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.51-1.91) or multiple times (multivariate OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.39-3.30) among AED users were not significantly different from those of nonusers.22 In their cross-sectional survey of 4696 Danish men aged 60 to 75 years, Masud et al.15 reported the OR of falls with AED use as 2.8 (95% CI: 1.5-5.1) and for recurrent falls with AED use as 2.6 (95% CI: 1.2-5.7). Tromp et al.’s25 study of 1469 men and women aged 65 years or older reported the highest OR of 6.2 (95% CI: 2.0-19.7) for falls and an OR of 7.1 (95% CI: 2.5-19.8) for recurrent falls with AED use.

Analysis of study quality

Study quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project’s quality assessment tool.21 Of the 7 studies, 6 were rated as weak and 1 rated of moderate quality using our global rating scale (Table 1). Most studies were rated poor because of missing information on blinding, data collection tools, proportions of males and females and methodology.

Discussion

In studies of older adult ambulatory populations, AED use was associated with an increased risk of falls, with RRs that ranged from 1.29 to 1.62 and ORs that ranged from 1.75 to 6.2, the CIs of which were all statistically significant. However, it is important to note that the CIs for ORs were large, bringing into question the precision of the estimate. The risk appeared higher for recurrent falls, but studies did not provide adequate data to calculate an overall increase in RR.

Carbone et al.’s27 prospective cohort study of more than 138,000 women (1385 AED users and 137,282 nonusers) was not included in our review because the mean age of participants (63 years) did not meet our inclusion criteria. Nonetheless, this study provides a wealth of data on falls associated with AED use. The authors compared the risk of 2 or more falls among AED users with that of nonusers, expressing findings as a hazard ratio (HR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.5-1.74) over a follow-up period of 7.7 years.27 The HR for patients who took AEDs for less than 2 years’ duration was 1.58 (95% CI: 1.40-1.79), for those who took AEDs for 2 to 5 years was 1.55 (95% CI: 1.36-1.76) and for those who took AEDs for more than 5 years was 1.71 (95% CI: 1.52-1.94).27 Given that these researchers found an association between AED use and falls in an ambulatory population younger than those in our clinical review, it is reasonable to assume that a similar magnitude of association—if not greater—would be seen in older adult populations because the propensity to fall increases with age.7

Psychotropic agents such as benzodiazepines, antidepressants and antipsychotics are also well known to increase the risk of falls. Meta-analyses of studies in older adult populations have reported an increased risk of falling with benzodiazepines (OR: 1.39-1.6), antidepressants (OR: 1.59-1.72), antipsychotics (OR: 1.5-1.71) and sedative-hypnotics (OR: 1.31-1.54).10-12,28 The similarity in fall risk ORs for different psychotropic medications, including benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, sedative-hypnotics and antiepileptic medications, suggests the need for medication reviews to justify continued use of these drugs in older adult patients. Although discontinuation is not always possible and could result in detrimental control of certain conditions, medication reviews should be conducted that balance need and effectiveness with safety of psychotropic agents, including AEDs, with a clear idea of expected outcomes from their use (Box 2). A lower initiation dose with monitoring and follow-up will promote the use of the lowest effective dose among older adults. Extra vigilance is especially needed for those with a prior history of falls, as well as those with comorbidities, such as peripheral neuropathy and hypoglycemic episodes from poor diabetes control, or imbalance and orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson’s disease, that predispose a person to an increased risk for falls (Box 2).

Box 2. Tips for pharmacists assessing fall risk from use of antiepileptic drugs.

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) increase the risk of falls in older adults. To lower fall risk, review all medications annually to assess their indication, efficacy and safety.

- Ensure the patient’s medication profile provides a comprehensive list of all prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications and natural health products. If unsure, ask the following questions:

- Have you filled prescriptions at another pharmacy in the past 3 months?

- Do you have more than 1 prescriber? Do you see any specialists?

- Are you taking any over-the-counter drugs or natural health products?

Evaluate the safety profiles of prescribed drugs, over-the-counter medications and natural health products to assess fall risk. Determine if lower doses or different administration schedules could decrease risk of falls.

Be aware of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of drugs that may increase the risk for falls.8

When assessing fall risk from medications, consider how comorbidities as well as medications used to treat them may increase risk of falls,8 for example, seizures and adverse effects from AEDs, peripheral neuropathy and hypoglycemic episodes from diabetes mellitus and imbalance and orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson’s disease.

Reevaluate drugs that do not have an indication and discuss the possibility of discontinuing them. If appropriate, in collaboration with the patient’s physicians and other health care providers, discontinue, titrate and taper drugs with no or inappropriate indications.

If drug therapy requires adjustment or discontinuation, create a plan to reduce the risk of harm, track progress and follow up on the outcome.

In their descriptive epidemiological study of epilepsy, Hauser and colleagues29 found that the incidence of epilepsy peaks in childhood and then increases again after about age 60. Similarly, Kotsopoulos and colleagues30 found that the age-specific incidence of epilepsy has a bimodal distribution—highest in childhood but also high and increasing among those aged 60 years or older. The number of prescriptions for AEDs has increased in older adult populations because of this second peak. In the United States and Europe, about 1% of ambulatory older adults are prescribed an antiepileptic medication for epilepsy.31-33 Although we reviewed only studies of ambulatory older adults living in the community, the prevalence of AED use is much higher—around 10%—among nursing home residents.34,35

Although AEDs are linked to hypocalcemia and decreased biologically active vitamin D levels, which lead to lower bone mineral density,36 a 2001 survey of neurologists revealed that only 28% of adult neurologists routinely assessed patients taking antiepileptics for bone and mineral disease.37 As this is a class of agents that not only increases the risk of falls but also reduces bone mineral density, it is important for health care professionals to be aware of the potential both for falls and for subsequent fracture injury, particularly among older adults.

A major limitation of this clinical review was the inability to perform a meta-analysis. Although the studies in this review reported RRs or ORs, they did not provide sufficient information on events in 1 or both groups and/or did not provide data on sample sizes in 1 or both groups to provide a summary measure. This is not surprising, given that the primary objective of many of the studies was not to assess the risk of falls and that many studies reported these results as secondary objectives or as findings that were revealed through additional analyses. In addition, studies that met our eligibility criteria included mostly cohort studies and were not designed to establish causality between AED use and falls.

Our initial database searches returned 49 studies published in languages other than English, some of which might have been excluded for other reasons. Given that our inclusion criteria had greatly reduced the number of studies published in English, it is possible that a similar reduction would have been seen in studies published in other languages. Nonetheless, our methodology introduced a potential bias that could influence results.

Another limitation of our review was the variability in follow-up duration and the outcome measures in the studies. Study duration varied from 1 year26 to a mean of 5.3 years.14 Similarly, some studies determined the risk of 2 or more falls,22,25 while others investigated falls only among AED users and nonusers.14,23,26 None of the studies measured adherence to AED or patterns of use. Our assessment of study quality (Table 1) also revealed that most were methodologically weak because of missing information on researcher and subject blinding, data collection tools, proportions of males and females and methodology. Although most studies have some methodological limitations, formally assessing limitations as part of clinical reviews may heighten awareness of the need for greater methodological rigor overall.

Finally, we were unable to determine the risk of falls associated with individual antiepileptic agents. Many studies either did not conduct analyses to determine the risk of falls with specific antiepileptics or did not report the analyses if conducted. The studies that focused on individual AEDs and their associated risk of falls had confounders such as patients with diabetic neuropathy, which could increase the risk of falls independent of AED use. Although an increased risk of falling from AED use has a biologically plausible mechanism, the statistical associations reported in this review might be attributable to other factors, among them preexisting conditions for which the AEDs were prescribed. To help elucidate association from causality, we suggest that a large randomized study on AED use in ambulatory older adults be conducted to assess the occurrence of falls prospectively as adverse events.

Conclusion

The RR of falls with AED use ranged from 1.29 to 1.62 and the ORs ranged from 1.75 to 6.2 (with large CIs) for 1 or more falls and 2.56 to 7.1 for recurrent falls. Despite this clinical review’s limitations, these findings can guide pharmacists and other clinicians to assess the risk of falls among ambulatory older adults and to balance the need for AEDs with the increased risk of falls resulting from these agents, particularly in light of the likelihood of polypharmacy in this population (see Box 2). Future studies with better-defined outcome measures (all falls, recurrent falls or any falls), duration of follow-up, adherence or use parameters, adjustment for confounding variables and determination of risk of falls with individual AEDs would provide clinicians with further guidance. ■

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicholas Chauvin, Melody Maximos and Gloria Jacobson for reviewing an earlier draft and Joe Petrik for copyediting and formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:M. Maximos conducted the literature search and analysis and contributed to the initial draft of the manuscript. F. Chang assisted with developing and finalizing the research question and reviewing and editing the manuscript. T. Patel developed the research question and assisted with data collection, analysis and interpretation and drafting and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Falls. Available: www.who.int.mediacentre/factsheets/fs344/en (accessed Oct. 1, 2016).

- 2. Public Health Agency of Canada. The facts: seniors and injury in Canada. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/publications/public/injury-blessure/safelive-securite/chap2-eng.php (accessed Oct. 1, 2016).

- 3. Zuckerman JD. Hip fracture. N Engl J Med 1996;334(23):1519-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Public Health Agency of Canada. Inventory of fall prevention initiatives in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Division of Aging and Seniors, Public Health Agency of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med 1997;337(18):1279-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. SMARTRISK. The economic burden of unintentional injury in Canada. 1998. Parachute Canada. Available: www.parachutecanada.org/downloads/research/reports/EBI1998-Can.pdf (accessed Oct. 1, 2016).

- 7. Dionyssiotis Y. Analyzing the problem of falls among older people. Int J Gen Med 2012;5:805-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang AR, Mallet L, Rochefort CM, et al. Medication-related falls in the elderly: causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging 2012;29(5):359-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62(10):1172-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47(1):30-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(21):1952-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47(1):40-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, et al. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2010;21(5):658-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cea-Soriano L, Johansson S, García Rodríguez L. Risk factors for falls with use of acid-suppressive drugs. Epidemiology 2013;24(4):600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masud T, Frost M, Ryg J, et al. Central nervous system medications and falls risk in men aged 60-75 years: the Study on Male Osteoporosis and Aging (SOMA). Age Ageing 2013;42(1):121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Theodore WH, Spencer SS, Wiebe S, et al. Epilepsy in North America: a report prepared under the auspices of the global campaign against epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, the International League Against Epilepsy and the World Health Organization. Epilepsia 2006;47(10):1700-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1993;34(3):453-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faught E, Richman J, Martin R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy among older U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Neurology 2012;78(7):448-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bulat T, Castle SC, Rutledge M, et al. Clinical practice algorithms: medication management to reduce fall risk in the elderly—part 4, anticoagulants, antiepileptics, anticholinergics/bladder relaxants and antipsychotics. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(4):181-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendeley. Free reference manager and PDF organizer. Available: https://www.mendeley.com (accessed Oct. 1, 2016).

- 21. Thomas H, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs 2004;2:91-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Mangione CM, et al. Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50(10):1629-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koski K, Luukinen H, Laippala P, et al. Physiological factors and medications as predictors of injurious falls by elderly people: a prospective population-based study. Age Ageing 1996;25:29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faulkner KA, Cauley JA, Studenski SA, et al. Lifestyle predicts falls independent of physical risk factors. Osteoporos Int 2009;20(12):2025-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tromp AM, Smit JH, Deeg DJ, et al. Predictors for falls and fractures in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Bone Miner Res 1998;13(12):1932-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. French DD, Campbell R, Spehar A, et al. Drugs and falls in community-dwelling older people: a national veterans study. Clin Ther 2006;28(4):619-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carbone LD, Johnson KC, Robbins J, et al. Antiepileptic drug use, falls, fractures and BMD in postmenopausal women: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). J Bone Miner Res 2010;25(4):873-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bloch F, Thibaud M, Dugué B, et al. Psychotropic drugs and falls in the elderly people: updated literature review and meta-analysis. J Aging Health 2011;23(2):329-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Rocca WA. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71(6):576-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kotsopoulos I, van Merode T, Kessels FGH, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence studies of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia 2002;43(11):1402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rochat P, Hallas J, Gaist D, et al. Antiepileptic drug utilization: a Danish prescription database analysis. Acta Neurol Scand 2001;104:6-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alacqua M, Trifirò G, Spina E, et al. Newer and older antiepileptic drug use in Southern Italy: a population-based study during the years 2003–2005. Epilepsy Res 2009;85:107-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Berlowitz DR, Pugh MJ. Pharmacoepidemiology in community-dwelling elderly taking antiepileptic drugs. Int Rev Neurobiol 2007;81:153-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lackner TE, Cloyd JC, Thomas LW, et al. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: effect of age, gender and comedication on patterns of use. Epilepsia 1998;39:1083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garrard J, Harms S, Hardie N, et al. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home admissions. Ann Neurol 2003;54:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ali II, Schuh L, Barkley GL, et al. Antiepileptic drugs and reduced bone mineral density. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5(3):296-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Valmadrid C, Voorhees C, Litt B, et al. Practice patterns of neurologists regarding bone and mineral effects of antiepileptic drug therapy. Arch Neurol 2001;58(9):1369-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]