Abstract

Introduction

Early reports of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in Europe suggested high complication rates and disappointing outcomes compared to publications from Japan. Since 2008, we have been conducting a nationwide survey to monitor the outcomes and complications of ESD over time.

Material and methods

All consecutive ESD cases from 14 centers in France were prospectively included in the database. Demographic, procedural, outcome and follow-up data were recorded. The results obtained over three years were compared to previously published data covering the 2008–2010 period.

Results

Between November 2010 and June 2013, 319 ESD cases performed in 314 patients (62% male, mean (±SD) age 65.4 ± 12) were analyzed and compared to 188 ESD cases in 188 patients (61% male, mean (±SD) age 64.6 ± 13) performed between January 2008 and October 2010. The mean (±SD) lesion size was 39 ± 12 mm in 2010–2013 vs 32.1 ± 21 for 2008–2010 (p = 0.004). En bloc resection improved from 77.1% to 91.7% (p < 0.0001) while R0 en bloc resection remained stable from 72.9% to 71.9% (p = 0.8) over time. Complication rate dropped from 29.2% between 2008 and 2010 to 14.1% between 2010 and 2013 (p < 0.0001), with bleeding decreasing from 11.2% to 4.7% (p = 0.01) and perforations from 18.1% to 8.1% (p = 0.002) over time. No procedure-related mortality was recorded.

Conclusions

In this multicenter study, ESD achieved high rates of en bloc resection with a significant trend toward better outcomes over time. Improvements in lesion delineation and characterization are still needed to increase R0 resection rates.

Keywords: Endoscopic submucosal dissection, endoscopic resection, early neoplasm, intramucosal cancer

Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), despite its first description by Japanese authors dating back to the early 2000s, has only recently been gaining momentum in Western countries.1,2 ESD allows en bloc resection of lesions exceeding 20 mm throughout the digestive tract, except in the duodenum where the outcomes are currently disappointing. ESD allows for a) an oncologically adequate resection, lowering the risk of local recurrence, and b) an optimal histological analysis of a single tissue sample, and is therefore a reliable assessment of the risk of lymphatic invasion.3 However, as a consequence of a relatively flat learning curve for this technique,4,5 only a few European centers have been able to perform as well as Japanese experts. Monitoring ESD cases in a European setting is a prerequisite to optimize the training of the endoscopists and define quality standards that are suitable for Western countries. This is particularly relevant for lesions that are more prevalent in the Western world than in Asia, such as Barrett’s esophagus-associated neoplasia or certain types of colorectal neoplasia.3,6

In 2007, the French Society for Digestive Endoscopy (Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive or SFED) started a nationwide survey among gastroenterologists performing ESDs. This survey was conducted among 16 centers and 22 endoscopists for the 2008–2010 period and provided a first picture of the practice of ESDs in a large Western country. One of the most striking findings of that study was a high complication rate of 29.2%.7 The SFED decided to extend the collection of data from this registry to the 2010–2013 period in order to assess the main trends in the practice of ESD in France.

Methods

Objectives

The main objective was to assess the improvements in ESD practice over time in terms of complication rates. Secondary objectives were to assess the improvements in ESD practice in terms of outcomes, to monitor the caseload of ESDs among the main endoscopy centers in France, and to compare the technical and procedural characteristics (location and type of lesions, devices used) of ESD over time.

Data collection

Case report forms were sent to all 21 gastroenterologists self-reportedly performing ESDs on a regular basis in 14 French centers making up the ESD Study Group, which already took part in the 2008–2010 survey. Two of the initial 16 centers declined participation because they had discontinued ESD. Out of 14 centers, nine were academic hospitals belonging to the public sector, one was a public, non-academic hospital, one was a private, non-profit hospital and three were private hospitals. In five centers (Cochin Hospital and Georges Pompidou European Hospital in Paris, Jean Mermoz in Lyon, Nantes and Avignon), more than one endoscopist performed ESDs, whereas every other center had only one regular ESD practitioner.

ESD Study Group members were asked to complete a case report form for all consecutive patients treated by ESD. Demographic, technical and procedural data, complications and outcomes of all ESDs performed in these centers were prospectively collected by each endoscopist. Data on the first two follow-up endoscopies, additional treatments, and pathology results were recorded. When complementary surgery had been performed, surgical and pathology reports were also collected. Endoscopic ultrasound and/or computed tomography (CT) scans were also performed before treatment in cases of suspected submucosal infiltration.

The decision to include a patient in the study was made by individual investigators, provided that cases complied with published descriptions of ESD techniques. All patients gave informed consent before undergoing ESD. The study received approval from the SFED Review Board. Data for the present registry were collected between November 2010 and June 2013, i.e. the same time span as the first registry (32 months).

ESD technique

All procedures were performed under deep sedation or general anesthesia, supervised by an anesthesiologist, with continuous propofol infusion and monitoring of cardiorespiratory function. All types and brands of endoscopes were allowed. Carbon dioxide insufflation was routinely used, while distal attachment cap was optional. The usual steps of ESD2 were followed: After delineation of the lesion, peripheral markings were made around the lesion using the tip of the ESD knife and coagulation; submucosal lifting was then performed using a 21- or 25-gauge injection needle and several kinds of dedicated solutions, such as 0.9% saline or 10% glycerol and 5% fructose in 0.9% saline, with indigo carmine staining and epinephrine adjunction, or hyaluronic acid. Peripheral incision was performed outside the markings using section or endocut mode, and any number or combination of commercially available Conformité Européene (CE)-marked ESD knives. After additional submucosal lifting, ESD was performed. High-frequency electrosurgical generators were used, and the settings chosen in accordance with the Japanese recommendations.8 Postoperative care and follow-up were left to the discretion of each team.

Histopathological analysis

Histological types of early gastrointestinal cancer were classified according to the Vienna classification.9 Besides histological type, pathology assessed the completeness of the resection by the invasion of horizontal and vertical margins, and histoprognostic factors for cancers, such as the grade of differentiation, the depth of invasion (measured in µm in case of submucosal invasion), and the presence of lymphatic or vascular invasion. In case of piecemeal resection, reconstruction of specimens was attempted by the endoscopist before fixation in 10% formalin.

Definitions

“Procedure duration” was defined as the time from insertion to removal of the endoscope.

Lesions located at the esophagogastric junction were classified as esophageal or gastric lesions depending on the side of their maximal extent and suspected origin while lesions located at the rectosigmoid junction were classified as colonic lesions.

“En bloc resection” was defined as a resection in a single piece of tissue, as opposed to a piecemeal resection. “En bloc-R0” resection was defined by the absence of neoplasia on the vertical and horizontal resection margins. Margins were also considered free of neoplasia when they contained non-dysplastic intestinal metaplasia in the stomach and esophagus. Curative endoscopic resection of carcinoma was defined as R0 resection of carcinoma, along with the absence of poor histoprognostic factors: grade 3 (poor) differentiation, lymphatic or venous invasion, or deep submucosal infiltration (>200 µm for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, >500 µm for Barrett’s and gastric neoplasia, and >1000 µm for colorectal neoplasms10).

“Bleeding” was defined as the occurrence of clinical symptoms and laboratory changes that indicated gastrointestinal bleeding after ESD. Intraprocedural bleeding treated during the initial endoscopy without requiring an additional endoscopy or a blood transfusion was not recorded as a complication. A diagnosis of perforation was pronounced upon direct endoscopic visualization of a deep defect of the muscularis propria, mediastinal or mesenteric fat, observation of free air on a plain X-ray or CT scan or need for per procedural peritoneal exsufflation. Subcutaneous emphysema was not recorded as a perforation when none of the aforementioned criteria were met.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad statistical software (La Jolla, CA, USA). The mean (±standard deviation or SD) was used to describe variables with normal distribution and the median (and interquartile range or IQR) for variables with a skewed distribution. Fischer’s exact test was used to compare categorical data. Means were compared using an unpaired t test. A p value below 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Patients and lesions

A total of 335 ESDs were performed in 330 patients between September 2010 and June 2013. Sixteen patients (and 16 ESDs) were excluded because of missing data, leaving 319 ESDs in 314 patients in the final analysis. All 14 centers included patients, and the median (IQR) number of ESD per center was 10 (4.5–44.5), as compared to six (3.25–13.5) for the 2008–2010 study period (p = 0.1). The number of patients included in each center increased from 0.37/month over the 2008–2010 period to 0.74/month over the 2010–2013 study period. Of note, 79.5% of cases were performed in four centers. Forty-five rectal ESDs performed in nine of the participating centers during the study period were included in another study, the results of which have been reported elsewhere11 and were not included in this survey.

Main patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most lesions were located in the stomach (n = 104, 32.6%); however, when compared to the 2008–2010 period, an increasing proportion of esophageal and colonic ESDs was performed (22.6% vs 14.4%, p = 0.03, and 16.3% vs 6.9%, p = 0.002, respectively). Mean lesion size increased from 32 to 39 mm (p = 0.004) between 2008–2010 and 2010–2013. The largest group of tumors (116, 36.4%) was made up of epithelial carcinomas. Most lesions were slightly elevated, with Paris 0–IIa, 0–IIa + IIb, 0–IIb, and 0–Is types described in 82 (25.7%), four (1.3%), 37 (11.6%), and 69 (21.6%) cases, respectively. Depressed or partly ulcerated lesions were reported in a minority of cases, with Paris 0-IIc, 0-IIa + IIc, 0–IIb + IIc, and 0–III types reported in five (1.6%), 16 (5%), four (1.3%) and one (0.3%) case, respectively. Finally, six (1.6%) Paris 0–Isp, mainly submucosal lesions, were reported. Noticeably, 24 (7.5%) submucosal lesions were resected, and 26 (8.2%) cases were local recurrences after a previous endoscopic resection.

Table 1.

Main clinical and pathological features of patients and lesions treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in 2008–2010 and 2010–2013

| 2008–2010 | 2010–2013 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ESD | 188 | 319 | |

| Age (mean ± SD), years | 64.6 ± 13 | 65.4 ± 12 | 0.5 |

| Men, n (%) | 114 (60.6) | 198 (62.1) | 0.7 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| Esophagus | 27 (14.4) | 72 (22.6) | 0.03 |

| Stomach | 75 (39.9) | 104 (32.6) | 0.1 |

| Duodenum | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 1 |

| Colon | 13 (6.9) | 52 (16.3) | 0.002 |

| Rectum | 72 (38.3) | 90 (28.2) | 0.02 |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD), mm | 32.1 ± 21 | 39 ± 23 | 0.004 |

| Histopathology, n (%) | |||

| Low-grade dysplasiaa | 40 (21.3) | 69 (21.6) | 1 |

| High-grade dysplasia | 48 (25.5) | 85 (26.7) | 0.8 |

| Carcinomab | 86 (45.7) | 116 (36.4) | 0.04 |

| Intramucosal carcinoma | 53 (28.2) | 87 (27.3) | 0.8 |

| Sm1 carcinoma | 33 (17.6) | 9 (2.8) | 0.007 |

| Sm2 or deeper carcinoma | 14 (7.4) | 20 (6.3) | 0.01 |

| Otherc | 49 (15.4) |

ESD: endoscopic submucosal dissection

Two sessile-serrated lesions were included in this group for the 2010–2013 period.

Only epithelial carcinomas were taken into account.

Other findings for the 2010–2013 time period included: endocrine tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or metastases (n = 18), non- or poorly malignant submucosal tumors (n = 9), inflammatory, hyperplastic or cicatricial mucosal findings (n = 22).

ESD procedures

Mean (±SD) procedure time was 108.2 ± 62 minutes, within a range of 37 to 330 minutes, as compared to 117.3 ± 69 minutes for the 2008–2010 period (p = 0.12).

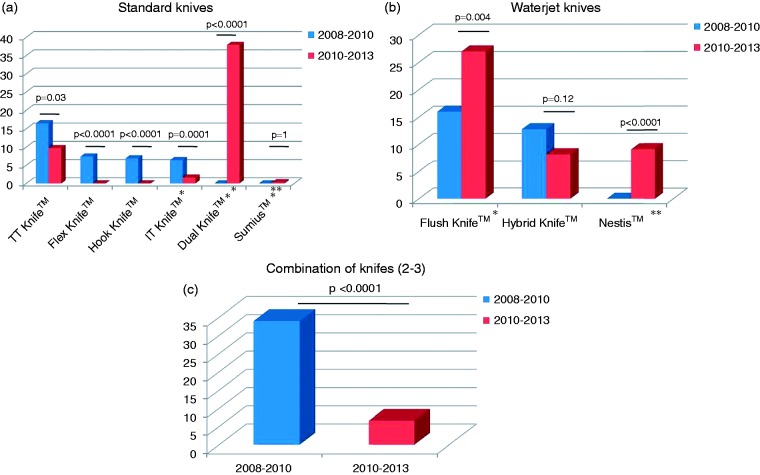

One single type of ESD knife was used in the majority of cases: a Dual knife™ (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a Flush knife™ (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) was used in 120 (37.9%) and 86 (27%) cases, respectively. The evolution in the choice of endoscopic devices is presented in Figure 1. Isotonic saline, hydroxyethyl starch (Voluven, Fresenius Kabi, France), sodium hyaluronate (Sigmavisc, Hyaltech, UK), a 10% glycerol and 5% fructose solution, and other submucosal lifting solutions were used in 54 (16.9%), 68 (21.3%), 99 (31%), and 52 (16.3%) cases, respectively. Adrenaline was used in 59 (90.1%) cases. A distal cap attachment was used in 94.7% of the procedures, as compared to the 83% rate for the 2008–2010 period (p = 0.0001). Hemoclips were less used (20.4% vs 31.9% of cases, p = 0.004) and hemostasis was more likely to be achieved with hemostatic forceps, used in 69.6% vs 35.1% of cases, p = 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection knifes used for endoscopic submucosal dissections performed in 2008–2010 vs 2010–2013.

Complications

We recorded a twofold decrease in the complication rate, from 55 (29.2%) to 45 (14.1%) cases, between 2008–2010 and 2010–2013 (p < 0.0001). Bleeding and perforation, occurring in 15 (4.7%) and 26 (8.1%) cases, respectively, required a second endoscopy in six (1.9%) cases, and surgery in one (0.3%) case. Complications are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main complications after endoscopic submucosal dissections (ESD) in 2008–2010 and 2010–2013

| 2008–2010 | 2010–2013 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ESD | 188 | 319 | |

| Any bleeding, n (%) | 21 (11.2) | 15 (4.7) | 0.01 |

| Bleeding requiring transfusion, n (%) | 4 (2.1) | 4 (1.3) | 0.5 |

| Perforation, n (%) | 34 (18.1) | 26 (8.1) | 0.002 |

| Perforation treated surgically, n (%) | 6 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0.001 |

| Total, n (%) | 55 (29.2) | 41 (12.9) | <0.0001 |

Four other complications were recorded, among which three were early complications (acute pulmonary edema, aspiration pneumonia, and acute urinary retention) and one was a late complication (esophageal stricture requiring dilation therapy). None of these complications required intensive care unit admission or caused death.

In one case, ESD was considered as a failure after 270 minutes of procedure, and the patient immediately underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery.

Early outcomes

En bloc resection rates significantly improved between 2008–2010 and 2010–2013, from 77.1% (145/188) in the first period to 91.5% (291/319), p < 0.0001. En bloc resection rates ranged from 42/52 (80.8%) for the colon to 71/72 (98.6%) for the esophagus. R0 resection rate among the 288 neoplastic lesions, either epithelial or submucosal, was 207/288 (71.9%), as compared to 137/188 (72.9%) for the 2008–2010 period (p = 0.8). Poor histoprognostic factors, such as lymphatic and vascular invasion or poor tumor differentiation, were seen in 16/116 (13.8%) of epithelial carcinomas. Thus, the curative resection rate for the 116 epithelial carcinomas was 75/116 (64.7%).

Main therapeutic outcomes are presented in Table 3, and therapeutic outcomes according to each lesion site are reported in Table 4. Median (IQR) hospital stay was three (one to four) days. In case of a complication, median (IQR) hospital stay was four (three to five) days, as compared to three (two to three) when no complication was recorded. These figures were stable compared to the 2008–2010 period.

Table 3.

Therapeutic outcomes after the endoscopic submucosal dissections (ESD) performed in 2010–2013

| Number of ESD = 319 | |

|---|---|

| En bloc resection, n (%) | 292/319 (91.5) |

| Overall R0 en bloc resection, n (%) | 277/319 (71.2) |

| R0 en bloc resectiona, n (%) | 207/288 (71.9) |

| R1 resectiona, n (%) | 71/288 (24.7) |

| Positive horizontal margins | 54/288 (18.8) |

| Positive vertical margins | 17 (5.9) |

| Rx resectiona, n (%) | 10/288 (3.5) |

| Grade 3 tumor differentiationb, n (%) | 10/116 (8.6) |

| Lymphatic or vascular invasionb, n (%) | 9/116 (7.8) |

Calculated for all neoplastic lesions, including the submucosal neoplasms.

Calculated for the epithelial carcinomas only.

Table 4.

Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissections (ESD) performed in 2010–2013 according to the lesion sites

| Lesion site | En bloc resection, n (%) | R0 en bloc resection,a n (%) | Recurrence rate,a,b n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagus | 71/72 (98.6) | 57/69 (82.6) | 4/60 (6.7) |

| Squamous cell neoplasia | 31/31 (100) | 26/31 (83.9) | 2/27 (7.4) |

| Barrett’s neoplasia | 38/38 | 31/38 (81.6) | 2/33 (6.1) |

| Stomach | 100/104 (96.2) | 71/83 (82.7) | 5/63 (7.9) |

| Duodenum | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 (0) | 0 |

| Colon | 42/52 (80.8) | 21/50 (42) | 1/42 (2.4) |

| Rectum | 78/90 (86.7) | 55/85 (68.2) | 5/64 (7.8) |

Calculated for all neoplastic lesions, including the submucosal neoplasms.

Calculated for the 229 patients with follow-up data.

The outcomes of ESD in terms of complication rates and R0 resection rate per center are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Main outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection per center.

Follow-up data

The results of the first follow-up endoscopy, performed a mean of 4.7 ± 4 months after ESD, were available for 229 (72.9%) patients. At first follow-up endoscopy, 194 (84.7%) had a complete endoscopic and histological remission; 12 (5.2%) had residual non-dysplastic intestinal metaplasia, in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus or chronic atrophic gastritis; 13 patients (5.7%) had low-grade dysplasia, two of whom had a background of Barrett’s esophagus. Overall, 208 (90.8%) patients were in remission at first endoscopic follow-up. High-grade dysplasia and residual neoplasia were found in seven (3%) and one (0.4%) patients, respectively, and incomplete healing with persistent mucosal ulceration and non-specific histology was found in two (0.9%) patients. Residual neoplasia and high-grade neoplasia were treated by another endoscopic resection in five patients, radiofrequency ablation in one patient, chemoradiotherapy in another one, and surgery in one last patient.

The mean follow-up period was 6.1 ± 5 months. Recurrence rates of neoplastic lesions according to lesions sites are presented in Table 4 and did not differ significantly from one another (p = 0.7). Recurrence rates of neoplastic lesions were 8.3% (2/24), 4.8% (2/42), and 6.7% (11/163) for lesions lesser than 20 mm, between 20 to 29 mm, and 30 mm or above, respectively (p = 0.8). Twenty-six patients had an additional treatment during follow-up. Eighteen patients underwent surgery for the following reasons: deep submucosal invasion in 10 cases (among which were three cases of poorly differentiated tumors), one failure of ESD, one case of positive vertical margins, three cases of lymphatic or vascular invasion, and two cases of early metachronous cancer. Of the latter, one consisted of three newly developed lesions arising in an atrophic gastritis diagnosed as metachronous cancers at the first follow-up endoscopy at four months and required total gastrectomy. The other patient had a second lesion arising in a Barrett’s esophagus with a suspected submucosal cancer, diagnosed nine months after the first ESD. Among the 18 patients undergoing surgery, the surgical specimen was free of tumor (pT0N0Mx) in five cases: one poorly differentiated colon carcinoma with deep submucosal invasion and lymphovascular invasion, one gastric intramucosal carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion, one esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with deep submucosal invasion, one colonic adenocarcinoma with deep submucosal invasion and positive lateral margins, and one gastric carcinoma with signet-ring cells and deep submucosal infiltration. Four patients with high-risk tumors or incomplete endoscopic resection but unfit for surgery underwent adjuvant chemoradiation or chemotherapy alone. Finally, four patients underwent radiofrequency ablation for remaining Barrett’s esophagus.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that the complication rate after ESD was divided by two from 29% to 14.1% (p < 0.0001) between 2008–2010 and 2010–2013. This rate is comparable with Japanese multicenter reports,12 and reflects the improving experience of French endoscopists.

We observed that the ESD caseload was rising, with a doubling in the number of cases per center and per month between the two study periods. Along with the number of cases, the mean size of the lesion (39 mm vs 32 mm, p = 0.04, for 2008–2010 vs 2010–2013, respectively) increased as well. Whereas early experience mainly included gastric and rectal ESDs, later experiences showed a significant increase in the frequency of esophageal and colonic ESDs. These more challenging cases might explain why more experienced endoscopists did not significantly reduce their procedural time between the two study periods. The apparent smaller proportion of carcinomas is likely to be explained by the inclusion of a few submucosal tumors in the T1sm tumor group in the 2008–2010 study.

The reasons for the improvements in the outcomes of ESD are multiple: First, two low-volume centers out of the 16 initial centers quit practicing ESD between the two study periods. Second, all of the 20 endoscopists continued their training in ESD on live pigs, with or without expert guidance, at least every year during the study period. Five followed at least two hands-on courses on animal models with Japanese experts during the period. Three visited experts in Japan to familiarize themselves with the devices and techniques. Finally, the cumulative caseload as well as the standardization of the procedure and the ESD devices probably also accounted for the improved results of ESD between the two periods.

The technique of ESD evolved towards more standardization, with the near-systematic use of a distal attachment cap and the limitation to one single type of ESD knife (94.7% and 93.4% of cases, respectively); endoscopists abandoned the first-generation ESD knives (Hook knife, TT knife, Flex knife), perceived as less safe, and focused on the Flush-knife™, which allows additional submucosal injection during ESD, and the Dual Knife™, a user-friendly and highly maneuverable device. Hemostasis was increasingly achieved with hemostatic forceps, while the use of argon plasma coagulation or endoclips dropped significantly. The smaller number of perforations might also explain the reduced frequency of endoclip use over the 2010–2013 study period.

While the en bloc resection rate improved for all lesion locations and overall between the two study periods (77.1% vs 91.5%, p < 0.0001, for 2008–2010 vs 2010–2013, respectively), the en bloc R0 resection rate was unchanged, from 72.9% (137/188) to 71.2% (227/319), p = 0.8. The significantly higher proportion of colonic lesions, in which tumors can be harder to delineate and technically more challenging to resect, could explain this stagnating R0 resection rate.

The management of complications changed between the two study periods: Bleeding and perforation rates decreased significantly, while transfusion rates were divided by two and surgical management of perforations divided by six. This suggests that adverse events were not only less frequent, but also less severe. Furthermore, this trend toward endoscopic or conservative treatment in the management of perforations is also in keeping with the most recent Japanese guidelines.12

Unlike Farhat et al., we did not observe an effect of the caseload per center on the complication rates or the R0 en bloc resection rates of ESD.7 This is probably explained by the unexpected good performances of the smallest centers. The most recent European Society of Gastrointestinal (ESGE) guidelines report that an endoscopist should have performed at least 30 to 40 ESD cases in patients to achieve satisfying results, and 80 ESD cases to achieve the same results as expert endoscopists.13 However, they did not specify a minimal annual caseload for a center to be proficient in ESD. An expert panel also failed to reach a consensus on the minimal caseload of ESD per center, or whether the technique should be restricted to expert centers.3 Furthermore, the Nagano ESD Study Group also failed to demonstrate a difference in the outcomes of ESD between “high-volume” and “low-volume” centers.14

Complete resection of neoplasia at three months was observed in more than 90% of cases. Recurrence rates were not significantly affected by tumor sites or size of the lesions. It has to be noted that five out of the 18 patients who ultimately underwent surgical resection actually had pT0N0 pathology. This finding suggests that although poor histoprognostic factors (lymphovascular invasion, poor tumor differentiation, R1 or Rx resection, deep submucosal invasion) generally prompt surgical management in the absence of serious comorbidities, the selection of patients with superficial cancers requiring surgery after ESD can be improved.

Three limitations of our study should be mentioned: first, follow-up data were missing in 90 patients and mean available follow-up time was only six months, meaning that late recurrences may have been overlooked. Second, the Paris type of lesions, the differentiation grade of the tumors, the Rx resection rates, or late outcome data had not been collected during the 2008–2010 survey; others, such as the R0 resection rates for carcinomas only, were not available: some desirable comparisons of histological outcomes between the 2008–2010 and the 2010–2013 study periods were therefore unavailable. Finally, since data were reported by each practicing physician, there might have been some outcome reporting bias in our survey.

In 2009, Neuhaus mentioned only 12 publications about ESD in Europe and underlined the lack of prospective European studies in the field as well as the dismal 25% en bloc resection rates of the first ESD attempts.1,15 In a recent statement position paper, Deprez et al. encouraged the creation of ESD registries.3 These should allow us to follow the improvement of the technique and to guide future educational interventions and training. Recently, a number of prospective studies involving ESD have been published in Europe.6,16–20 However, these data focus on one organ and are monocentric: therefore, they reflect the performances of only one or two endoscopists. Only two prospective registry studies have assessed the outcomes of ESDs in a prospective multicenter setting.7,11 Rahmi et al. reported the outcomes of ESDs for 45 rectal lesions in nine French expert centers and found en bloc resection rate, R0 resection rate, bleeding and perforation rates of 64%, 53%, 18% and 13%, respectively.11 The results from Farhat et al., with which we compared the present data, were obtained in similar settings as the current work, but at an earlier period. They also showed high rates of complications (11.2% bleeding and 18.1% perforation) that commanded urgent improvements in ESD training in France for ESD to develop beyond the hands of a few experts.7 For instance, Probst et al., who also reported their early experience of ESD for various gastrointestinal lesions, had only a 9.7% and 4.9% incidence rate of bleeding and perforations, respectively,5 possibly reflecting the high expertise and training level of the single endoscopist who performed most of the procedures.

In our study, complication rates were significantly lower than in the 2008–2010 period. In addition, the 91.5% en bloc resection rate significantly improved and now meets Japanese standards.12 However, the 71.9% en bloc R0 resection rate remains limited. The experience of other European teams, who also reached a 72% R0 resection rate after four years of practice,5 suggests that the R0 resection rate reflects not only the technical ability to resect en bloc, but also the ability to accurately delineate the lesion. This last point, pertaining to the quality of diagnostic endoscopy, may need more time to improve.

In conclusion, this is the largest prospective registry on ESD outside Japan. The large number of centers participating allows us to hypothesize that the data presented are representative of the majority of ESD cases performed in France during the study period. Compared to the 2008–2010 period, the complication and en bloc resection rates met the Japanese standards, while R0 resection rates remained relatively low. Further training of endoscopists in lesion characterization and delineation is the next step to improve the outcomes of ESD.

Acknowledgments

The Authors wish to thank Mr Olivier Cerles, MSc, and Mr Philippe Sultanik, MD, PhD, for their valuable help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Neuhaus H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Present and future view of Europe. Dig Endosc 2009; 21(Suppl 1): S4–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers and large flat adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3(7 Suppl 1): S74–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deprez PH, Bergman JJ, Meisner S, et al. Current practice with endoscopic submucosal dissection in Europe: Position statement from a panel of experts. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatt A, Abe S, Kumaravel A, et al. Indications and techniques for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Probst A, Golger D, Arnholdt H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers, flat adenomas, and submucosal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevaux JB, Piessevaux H, Jouret-Mourin A, et al. Clinical outcome in patients treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial Barrett’s neoplasia. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farhat S, Chaussade S, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in a European setting. A multi-institutional report of a technique in development. Endoscopy 2011; 43: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isomoto H, Yamaguchi N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in the era of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2009; 44: 205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000; 47: 251–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the Paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahmi G, Hotayt B, Chaussade S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial rectal tumors: Prospective evaluation in France. Endoscopy 2014; 46: 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, et al. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc 2015; 27: 417–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 829–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hotta K, Oyama T, Akamatsu T, et al. A comparison of outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric neoplasms between high-volume and low-volume centers: Multi-center retrospective questionnaire study conducted by the Nagano ESD Study Group. Intern Med 2010; 49: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosch T, Sarbia M, Schumacher B, et al. Attempted endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal tumors using insulated-tip knives: A pilot series. Endoscopy 2004; 36: 788–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bialek A, Pertkiewicz J, Karpińska K, et al. Treatment of large colorectal neoplasms by endoscopic submucosal dissection: A European single-center study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuhaus H, Terheggen G, Rutz EM, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection plus radiofrequency ablation of neoplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probst A, Aust D, Märkl B, et al. Early esophageal cancer in Europe: Endoscopic treatment by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy 2015; 47: 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Probst A, Golger D, Anthuber M, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection in large sessile lesions of the rectosigmoid: Learning curve in a European center. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schumacher B, Charton JP, Nordmann T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric neoplasia with a water jet-assisted knife: A Western, single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 1166–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]