Abstract

Background and objectives

The role of prophylactic pancreatic stenting (PS) in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) has yet to be determined. Most previous studies show beneficial effects in reducing PEP when prophylactic pancreatic stents are used, especially in high-risk ERCP procedures. The present study aimed to address the use of PS in a nationwide register-based study in which the primary outcome was the prophylactic effect of PS in reducing PEP.

Methods

All ERCP-procedures registered in the nationwide Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and ERCP (GallRiks) between 2006 and 2014 were studied. The primary outcome was PEP but we also studied other peri- and postoperative complication rates.

Results

Data from 43,595 ERCP procedures were analyzed. In the subgroup of patients who received PS with a total diameter ≤ 5 Fr, the risk of PEP increased nearly four times compared to those who received PS with a total diameter of >5 Fr (OR 3.58; 95% CI 1.40–11.07). Furthermore, patients who received PS of >5 Fr and >5 cm had a significantly lower pancreatitis frequency compared to those with shorter stents of the same diameter (1.39% vs 15.79%; p = 0.0033).

Conclusions

PS with a diameter of >5 Fr and a length of >5 cm seems to have a better protective effect against PEP, compared to shorter and thinner stents. However, in the present version of GallRiks it is not possible to differentiate the exact type of pancreatic stent (apart from material, length and diameter) that has been introduced, so our conclusion must be interpreted with caution.

Keywords: ERCP, pancreatic stents, pancreatitis, complication rates, prophylaxis

Introduction

Pancreatitis occurring after endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) is a common and feared complication.1–8 Repeated cannulation of the pancreatic duct, contrast injection, especially to the point of acinar opacification, difficult bile duct cannulation as well as pre-cut sphincterotomy are some of the factors associated with an increased risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).1–5,8–10

A number of prophylactic measures to minimize the risk of PEP have been suggested. One is of course connected to the prophylactic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), a strategy that seems to steadily be becoming more generally accepted.11 On the other hand a number of issues have been specified concerning the value of a postprocedural facilitation of the drainage of pancreatic juice through the use of stents. For instance, it has been claimed that prophylactic pancreatic stenting (PS) in high-risk ERCPs, such as when the pancreatic duct has been cannulated, decreased the risk by facilitating the drainage of pancreatic juice into the duodenum. Several previous studies have shown beneficial effects from prophylactic PS in reducing PEP.12–28 However, the issue of diameter of the pancreatic stent is addressed in only a few studies, mostly single-center reports, and with conflicting results.29–33

In a recent meta-analysis, it was concluded that larger stents (5 Fr vs 3 Fr) had a better protective effect against PEP in high-risk ERCP procedures, but the outcome of using even larger (>5 Fr) stents requires further documentation.29

The aim of this study was to analyze whether PS in ERCP procedures in which the pancreatic duct has been cannulated unintentionally decreases the frequency of PEP. The data used were retrieved from a national validated population-based registry offering the power of a unique sample size of the study cohort to address the protective effect of PS in preventing PEP in ERCP.

Material and methods

Study design

The Swedish National Registry for Gallstone Surgery and ERCP (GallRiks) was established May 1, 2005 as a validated registry of cholecystectomies and ERCP procedures.34,35 The aim of the registry is to obtain a complete database including demographics and patient characteristics, indication and treatment methods, as well as outcome, using an online registration platform. For patients undergoing an ERCP, procedure-related information includes bile and/or pancreatic duct cannulation, whether sphincterotomy was performed and any additional diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Intra-procedural adverse events are registered by the endoscopist. At 30-day follow-up, all medical records are reviewed and post-procedural adverse events reported online in the registry by a local non-physician coordinator appointed at the respective units. GallRiks includes data from almost all Swedish hospitals performing ERCP. Matching GallRiks data with the Swedish National Patient Registry in 2014 showed that 88% of performed ERCP procedures in Sweden at that stage were registered in GallRiks. The data are validated regularly by an independent audit group that compares register data to in-patient records. There was a complete match between registry data and patient medical records in 98% of patients with a 100% concordance for bile duct injuries.35

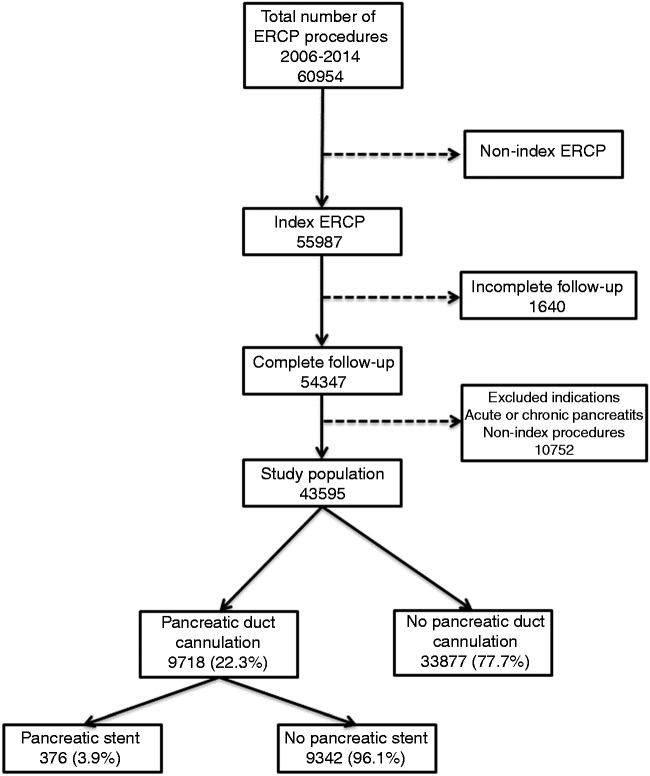

We conducted a nationwide population-based nested case-control study within the cohort of ERCP procedures entered in GallRiks between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2014. Patients for whom the indication was acute pancreatitis or chronic pancreatitis, ERCP procedures that were not index procedures and patients who had an incomplete 30-day follow-up or missing data were excluded. Furthermore, only patients for whom the intention, as documented by the indication for the investigation, was a selective cannulation of the bile duct (i.e. no intention to cannulate the pancreatic duct) were included (Figure 1). The outcomes studied were general intra- and post-procedural adverse events, specifically ERCP-associated adverse events like pancreatitis and bleeding.

Figure 1.

The profile of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) procedures included in the analysis.

Definitions

For the purpose of this paper, and in accordance with descriptions in the GallRiks database, adverse events were defined and described as per consensus agreement.

Index procedures were defined as the first ERCP in every in-hospital treatment episode within 30 days.

Intra-procedural adverse events were defined as bleeding, extravasation of contrast, perforation or any other reason for the ERCP being terminated prematurely.

Post-procedural adverse events were defined as any complication during the 30-day follow-up period that required some form of medical or surgical intervention.

Pancreatic cannulation is defined as deep or superficial cannulation of the pancreatic duct with subsequent contrast injection.

Pancreatitis was defined as abdominal pain in the presence of an elevated amylase at least three times above normal, at a time point more than 24 hours after terminating the ERCP procedure.

Procedure-related hemorrhage was defined as bleeding that required an intervention or blood transfusion.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 9.0.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Comparisons of patient and procedure characteristics were presented in contingency tables with pair-wise differences analyzed with Pearson’s Chi-square test and presented as p values. The association between pancreatic duct cannulation and the risk of adverse events, as defined above, were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression modeling. Variables that were statistically significant in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model as described by Hosmer et al.36

In the multivariate analysis the outcome was adjusted for age (dichotomized into more or less than 70 years), gender, comorbidity (dichotomized into American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 1–2 and ASA ≥3), urgent or elective procedures, indication and previous sphincterotomy having been performed.

Similar regression modeling was used on the subgroup of patients with a pancreatic duct cannulation, analyzing adverse effects depending on the placement of a pancreatic stent or not. In a final subanalysis, patients receiving PS were dichotomized into two groups, depending on if the total pancreatic stent diameter was >5 Fr or ≤5 Fr as well as dichotomized into two groups depending on the length of the single pancreatic stent (>5 cm or ≤5 cm) and analyzed for adverse events.

The models were tested for multicollinearity and effect modification and finally assessed for goodness of fit. The effects of analyzed variables were presented as odds ratios (ORs) for adverse events with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Ethics considerations

The regional research ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study.

Results

Between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2014, a total of 60,954 ERCP procedures were registered in GallRiks, of which 43,595 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The demographics of the study population and indications for ERCP are shown in Table 1. A total of 9718 patients (22.3% of the study population) had a pancreatic cannulation and of those one or more pancreatic stents were inserted in 376 patients (3.9%) (Figure 1). In the group in which the pancreatic duct was cannulated the risk of PEP was increased threefold (OR 3.07; 95% CI 2.77–3.40), compared to those without pancreatic duct cannulation. Furthermore, intraoperative as well as postoperative adverse events were significantly increased when the pancreatic duct was cannulated (Table 2). In those in whom the pancreatic duct was cannulated and a pancreatic stent inserted there was a twofold increase in intraoperative adverse events, compared to patients who did not receive a stent. Otherwise there were no differences in postoperative adverse events, pancreatitis and bleeding between the two groups (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis patients who received pancreatic stents with a total diameter of ≤5 Fr had an almost fourfold increase in the PEP-rate compared to those receiving stents with a total diameter of >5 Fr (OR 3.58; 95% CI 1.40–11.07) (Table 4). The stent diameter did not, however, affect the other registered adverse events. In a subgroup analysis in which the length of the pancreatic stent was taken into consideration, a significantly lower pancreatitis frequency was found in those who received a pancreatic stent with both the diameter >5 Fr and a stent length >5 cm (Table 5).

Table 1.

Demographics and indications for the 43,595 patients included in the study

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 23,151 | 53.1 |

| Male | 20,444 | 46.9 |

| Age (years)a | ||

| >70 | 23,576 | 54.2 |

| ≤70 | 19,923 | 45.8 |

| ASA | ||

| ASA score 1–2 | 28,967 | 66.4 |

| ASA score ≥3 | 14,628 | 33.6 |

| Acute/Scheduled | ||

| Acute | 30,664 | 70.3 |

| Scheduled | 12,931 | 29.7 |

| Indications | ||

| Obstructive jaundice | 11,802 | 27.1 |

| Cholangitis/sepsis | 4567 | 10.5 |

| Malignancy | 5534 | 12.7 |

| Suspected bile leakage | 805 | 1.9 |

| Suspected CBDS | 16,493 | 37.8 |

| Suspected PSC | 1055 | 2.4 |

| Prophylaxis against biliary pancreatitis | 536 | 1.2 |

| Stent dysfunction | 2803 | 6.4 |

Age missing in 96 (0.2%). ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CBDS: common bile duct stones; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Table 2.

Adverse event rates with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between patients undergoing ERCP with or without pancreatic duct (P-duct) cannulation

| Adverse events |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-duct cannulation |

No P-duct cannulation |

||||

|

n = 9718 |

n = 33877 |

||||

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Intraoperative | 402 | 4.1 | 848 | 2.5 | <0.0001 |

| Postoperative | 1645 | 16.9 | 4445 | 13.1 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatitis | 764 | 7.9 | 877 | 2.6 | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding | 134 | 1.4 | 406 | 1.2 | 0.1563 |

| Adverse events |

|||||

| P-duct cannulation vs no cannulation |

|||||

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

||||

| Odds ratio |

(95% CI) | Odds ratio | (95% CI) | p | |

| Intraoperative | 1.68 | (1.49–1.90) | 1.52 | (1.35–1.73) | <0.0001 |

| Postoperative | 1.35 | (1.27–1.43) | 1.44 | (1.35–1.54) | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatitis | 3.21 | (2.91–3.55) | 3.07 | (2.77–3.40) | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding | 1.15 | (0.94–1.40) | 1.12 | (0.91–1.37) | 0.2674 |

Adjusted for sex, age, ASA score, acute, indications, previous sphincterotomy. ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 3.

Adverse event rates and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in ERCP patients with pancreatic duct cannulation, with or without pancreatic stenting

| Adverse events |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic stent |

No pancreatic stent |

||||

|

n = 376 |

n = 9342 |

||||

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Intraoperative | 31 | 8.2 | 371 | 4.0 | <0.0001 |

| Postoperative | 62 | 16.5 | 1583 | 16.9 | 0.8173 |

| Pancreatitis | 30 | 8.0 | 734 | 7.9 | 0.9315 |

| Bleeding | 6 | 1.6 | 128 | 1.4 | 0.7130 |

| Adverse events |

|||||

| Pancreatic stent vs no pancreatic stent |

|||||

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

||||

| Odds ratio |

(95% CI) | Odds ratio | (95% CI) | p | |

| Intraoperative | 2.17 | (1.46–3.13) | 2.28 | (1.52–3.31) | 0.0001 |

| Postoperative | 0.97 | (0.73–1.27) | 0.91 | (0.68–1.20) | 0.5137 |

| Pancreatitis | 1.02 | (0.68–1.46) | 1.11 | (0.74–1.61) | 0.5958 |

| Bleeding | 1.17 | (0.46–2.44) | 1.16 | (0.45–2.47) | 0.7345 |

Adjusted for sex, age, ASA score, acute, indications, previous sphincterotomy. ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 4.

Adverse event rates and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence Intervals (CIs) in ERCPs with pancreatic duct cannulation and pancreatic stenting with diameters ≤5 Fr or >5 Fr

| Pancreatic stents |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse events |

|||||

| ≤5 Fr |

>5 Fr |

||||

|

n = 241 |

n = 135 |

||||

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Intraoperative | 22 | 9.1 | 9 | 6.7 | 0.4050 |

| Postoperative | 40 | 16.6 | 22 | 16.3 | 0.9398 |

| Pancreatitis | 25 | 10.4 | 5 | 3.7 | 0.0220 |

| Bleeding | 4 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.8947 |

| Pancreatic stents |

|||||

| Adverse events |

|||||

| Pancreatic stent ≤5 Fr vs >5 Fr |

|||||

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

||||

| Odds ratio |

(95% CI) | Odds ratio | (95% CI) | p | |

| Intraoperative | 1.41 | (0.65–3.31) | 1.39 | (0.64–3.28) | 0.4145 |

| Postoperative | 1.02 | (0.58–1.83) | 1.14 | (0.64–2.09) | 0.6517 |

| Pancreatitis | 3.01 | (1.22–9.09) | 3.58 | (1.40–11.07) | 0.0063 |

| Bleeding | 1.12 | (0.22–8.17) | 1.27 | (0.24–9.28) | 0.7856 |

Adjusted for sex, age, ASA score, acute indications, previous sphincterotomy.

Table 5.

Pancreatitis frequency correlated to pancreatic stent length and diameter

| Pancreatitis (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Fr | >5 Fr | p | |

| ≤5 cm | 9.4 | 6.5 | 0.5403 |

| >5 cm | 15.8 | 1.4 | 0.0033 |

| p | 0.2329 | 0.1329 | 0.0252 |

Only single pancreatic stents are included.

Discussion

This study is to our knowledge to date the largest patient cohort in which the effect of prophylactic PS on the risk of developing procedural-related complications has been evaluated. The most striking finding of the study was that the post-cannulation decompression of the pancreatic duct, in patients in whom the duct was inadvertently cannulated, with a pancreatic stent with a diameter >5 Fr and a length >5 cm was superior to a stent ≤5 Fr and ≤5 cm, in preventing PEP. In fact, we registered an almost fourfold increase in PEP when stents ≤5 Fr were used compared to stents with a diameter of >5 Fr. The increased risk of adverse events, including pancreatitis, if the pancreatic duct was cannulated inadvertently, is in line with previous studies.1–6,8–10 However, the finding that inserting the pancreatic stent increased the risk of intraoperative adverse events was contrary to most previous reports in the literature.12–28 A possible explanation for this could be that endoscopists were more prone to use PS in more complicated ERCP procedures, skewing the results in favor of the non-stented cases, a confounder that could not be fully compensated for even in the multivariate analysis.

In a study in which 249 high-risk ERCP patients were randomized to receive either a long 3 Fr or a short 5Fr pancreatic stent, Chahal et al. concluded that long 3 Fr stents were inferior, as this group had more adverse effects, experienced more stent failures and required more ERCP procedures for stent extraction, as the long 3 Fr stents did not dislodge spontaneously.30 The design of the study, in which both length and diameter varied between the groups, jeopardizes the interpretation of the results, but the overall conclusion of the study, advocating larger stent diameters for better results, is supported by the present findings. The contradictory findings in the literature are exemplified by the study of Pakh et al., who could not show any difference in PEP when comparing 4 Fr and 5 Fr stents and of Rashdan et al., who claimed that lesser diameter stents gave even better results.32,33 In a recent meta-analysis it was concluded that larger stents (5 Fr vs 3 Fr) had a better protective effect against PEP in high-risk ERCP procedures, but the outcome of using even larger (>5 Fr) stents requires further documentation.29 It is interesting to note that in total six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) could collect almost the same number of patients at risk as we prospectively incorporated into this population-based register defined as our target cohort.

Moreover, the use of longer rather than shorter stents has been advocated, arguing that they will remain in the pancreatic duct for a longer period of time, thereby ensuring prolonged decompression with subsequent lowering of the risk for PEP.33 This is in accord with the present results in which stents longer than 5 cm protected better against pancreatitis than shorter stents with the same diameter (>5 Fr). However, even these aspects are controversial since Chahal et al. advocated shorter stents, since the likelihood of spontaneous stent migration minimizes the number of patients requiring a repeat ERCP for stent extraction.30 Information regarding spontaneous stent dislodgement vs the need for repeat ERCP for stent extraction was not possible to extract from the GallRiks registry.

The major strength of this study is the population-based design, analyzing prospectively collected data from a validated database.34,35 The large number of ERCP procedures with inadvertent pancreatic duct cannulation (n = 9718) renders robust statistical power. Furthermore, the nationwide recruitment of a study population represents the complete spectrum of indications for ERCP performed at endoscopy units of varying sizes, by endoscopists with different levels of experience.

Inevitably this study has weaknesses. There is an unavoidable risk of selection bias, as the GallRiks database does not specify the actual indication for placing of the pancreatic stent. In an attempt to circumvent and neutralize this problem, only patients for whom the indications for the investigation necessitated cannulation of the bile duct only were included, whereupon it is most likely that cannulation of the pancreatic duct was unintentional. Furthermore, in the absence of randomization there is a risk of confounding by indication. For instance, the endoscopist might be more prone to performing PS in more complicated ERCP procedures. There might also be cases of inadvertent pancreatic duct cannulation not noticed by the endoscopists and therefore not registered in the GallRiks registry. The small number of patients who had pancreatic duct cannulation and underwent PS (3.9%) is of some concern. In this context it shall, however, be recalled that as many as 376 patients were enrolled into the target study group. Why the results shall be interpreted with some caution is reflected by the rather wide CIs.

The long duration of the registration period (2006–2014) to be enrolled for the current observations needs to be carefully considered. Both the radiological and endoscopic techniques and the indications of the ERCP procedures have changed over the corresponding time period, which may well affect the complication rates. Ideally, a more recent inclusion period would theoretically have offered outcome better reflecting the current practice. The downside of a similar preference would be a severe compromise of the number of patients who received prophylactic PS.

Another potential methodological problem with the present study is the lack of information on the use of rectally administered NSAIDs for PEP prophylaxis.11 This parameter has not traditionally been registered in the GallRiks registry. This deficiency of the registry has, however, been taken into consideration by the board of the GallRiks and from 2016 and onwards it will be mandatory to state whether an NSAID was administered or not. During the main time period of data collection in the present study cohort, the use of NSAIDs has not been practiced in the country.

Another issue relevant to the interpretation of the results is on which grounds the endoscopists chose the diameter of the pancreatic stent. Logically the diameter was chosen considering the size of the pancreatic duct as it was depicted on the pancreatogram, whereas a larger pancreatic duct would have resulted in a larger stent and vice versa. In order to compensate for this uncertainty, patients for whom the indication of the ERCP was chronic pancreatitis, often associated with a dilated duct, were excluded. Chronic pancreatitis per se is also known to protect against PEP.37 Furthermore, one limitation is also that it is not possible to specify the exact type of pancreatic stent (apart from material, length and diameter) in GallRiks. However, this shortcoming of the register is now under revision and by fall 2016 it will be possible to specify whether the stent is expected to dislodge spontaneously.

Another confounder is the level of experience of the endoscopists. This factor was not stratified for nor were the number of examinations performed by endoscopic trainees. Finally, precut sphincterotomy is a known risk factor for adverse events after ERCP, albeit the PEP may not be the predominant one, but still we were unable to control for this intervention.2–4

In conclusion, this nationwide, population-based cohort study suggests that PS with an assumed prophylactic indication using stents with a total diameter >5 Fr significantly reduces the risk of PEP compared to smaller stents. Furthermore, a >5 Fr pancreatic stent >5 cm in length significantly reduces pancreatitis frequency compared with shorter stents of the same diameter.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions include: Study concepts: GO, UA, LL and LE; study design: GO, JL, UA and LE; data acquisition: GO; quality control of data and algorithms: GO, JL, UA, EJ and LE; data analysis and interpretation: GO, JL, BT and LE; statistical analysis: BT and LE; manuscript preparation: GO, JL and LE; manuscript editing: EJ, UA, LL and LE; and manuscript review: EJ, UA, LL and LE. All authors have approved the final draft submitted. Lars Enochsson, MD, PhD, is guarantor of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm County Council and Futurum, Region Jönköpings Län.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: A systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 1781–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng CL, Sherman S, Watkins JL, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54: 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glomsaker T, Hoff G, Kvaløy JT, et al. Patterns and predictive factors of complications after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: A prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, et al. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Li ZS, Liu F, et al. Risk factors for ERCP-related complications: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, et al. Risk factors for complication following ERCP; results of a large-scale, prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 2007; 39: 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar A, Abu Dayyeh BK, Baron TH, et al. Rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are superior to pancreatic duct stents in preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cha SW, Leung WD, Lehman GA, et al. Does leaving a main pancreatic duct stent in place reduce the incidence of precut biliary sphincterotomy-associated pancreatitis? A randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 77: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhary A, Bechtold ML, Arif M, et al. Pancreatic stents for prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 73: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, et al. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline—updated June 2014. Endoscopy 2014; 46: 799–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, et al. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 57: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 62: 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, et al. Can pancreatic duct stenting prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who undergo pancreatic duct guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 1183–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Omata F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of pancreatic stenting to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 1635–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazaki T, Masuda H, Takayama T. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 842–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazaki T, Mado K, Masuda H, et al. Prophylactic pancreatic stent placement and post-ERCP pancreatitis: An updated meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49: 343–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan XP, Dang T, Meng XM, et al. Clinical study on the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis by pancreatic duct stenting. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011; 61: 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saad AM, Fogel EL, McHenry L, et al. Pancreatic duct stent placement prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction but normal manometry results. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67: 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi QQ, Ning XY, Zhan LL, et al. Placement of prophylactic pancreatic stents to prevent post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 7040–7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh P, Das A, Isenberg G, et al. Does prophylactic pancreatic stent placement reduce the risk of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis? A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 60: 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smithline A, Silverman W, Rogers D, et al. Effect of prophylactic main pancreatic duct stenting on the incidence of biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy-induced pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Gastrointest Endosc 1993; 39: 652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Mukai T, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stents reduce the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 851–858. quiz e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, et al. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology 1998; 115: 1518–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuchiya T, Itoi T, Sofuni A, et al. Temporary pancreatic stent to prevent post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A preliminary, single-center, randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007; 14: 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afghani E, Akshintala VS, Khashab MA, et al. 5-Fr vs. 3-Fr pancreatic stents for the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2014; 46: 573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chahal P, Tarnasky PR, Petersen BT, et al. Short 5Fr vs Long 3Fr pancreatic stents in patients at risk for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 834–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iqbal S, Shah S, Dhar V, et al. Is there any difference in outcomes between long pigtail and short flanged prophylactic pancreatic duct stents? Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pahk A, Rigaux J, Poreddy V, et al. Prophylactic pancreatic stents: does size matter? A comparison of 4-Fr and 5-Fr stents in reference to post-ERCP pancreatitis and migration rate. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 3058–3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rashdan A, Fogel EL, McHenry L, et al. Improved stent characteristics for prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enochsson L, Thulin A, Österberg J, et al. The Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks): A nationwide registry for quality assurance of gallstone surgery. JAMA Surg 2013; 148: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rystedt J, Montgomery A, Persson G. Completeness and correctness of cholecystectomy data in a national register—GallRiks. Scand J Surg 2014; 103: 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosmer DW, Taber S, Lemeshow S. The importance of assessing the fit of logistic regression models: A case study. Am J Public Health 1991; 81: 1630–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iorgulescu A, Sandu I, Turcu F, et al. Post-ERCP acute pancreatitis and its risk factors. J Med Life 2013; 6: 109–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]